Abstract

Common pathways and mechanisms can be found in both cancers and inborn errors of metabolism. 2‐Hydroxyglutarate (2‐HG) acidurias and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1/2 mutant tumors are examples of this phenomenon. 2‐HG can exist in two chiral forms, D(R)‐2‐HG and L(S)‐2‐HG, which are elevated in D‐ and L‐acidurias, respectively. D‐2‐HG was subsequently discovered to be synthesized in IDH 1/2 mutant tumors including ∼70% of intermediate‐grade gliomas and secondary glioblastomas (GBM). Recent studies have revealed that L‐2‐HG is generated in hypoxia in IDH wild‐type tumors. Both 2‐HG enantiomers have similar structures as α‐ketoglutarate (α‐KG) and can competitively inhibit α‐KG‐dependent enzymes. This inhibition modulates numerous cellular processes, including histone and DNA methylation, and can ultimately impact oncogenesis. D‐2‐HG can be detected in vivo in glioma patients and animal models using advanced imaging modalities. Finally, pharmacologic inhibitors of mutant IDH 1/2 attenuate the production of D‐2‐HG and show great promise as therapeutic agents.

Keywords: 2‐hydroxyglutarate, epigenetics, isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations, methylation

IDH 1/2 Mutations in Gliomas

IDH 1 mutations were first discovered by next‐generation sequencing studies in 12% of glioblastomas (GBM) 71. This intriguing finding prompted a more comprehensive analysis of a variety of gliomas including World Health Organization (WHO) grade II and grade III tumors, leading to the surprising detection of both IDH 1/2 mutations in ∼70% of grade II and grade III gliomas and GBM that arise from these intermediate‐grade lesions (termed secondary GBM) 7, 101. Subsequently, IDH 1/2 mutations have been found in other cancers, including acute myeloid leukemia, chondrosarcomas, Ollier and Maffucci syndromes (characterized by multiple central cartilaginous tumors), cholangiocarcinomas, angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma and rare cases of melanoma, colon, adult medulloblastoma and thyroid cancers 2, 3, 9, 10, 58, 69, 81, 95, 96, 102. IDH 1/2 mutant gliomas occur more frequently in young adult patients and are very rare in children 37, 49, 59, 61, 98, 101.

The discovery of IDH 1/2 mutations in gliomas has significantly impacted our clinical approach to glioma patients. IDH 1/2 mutations in high‐ and low‐grade gliomas confer a favorable prognosis relative to wild‐type tumors. Further, IDH 1/2 mutations in grade II and grade III gliomas have a better outcome regardless of WHO grade, while wild‐type tumors tend to behave like GBM 11, 29, 35, 39, 50, 75, 87. Thus, the IDH mutational status is paramount in intermediate‐grade gliomas 31. From a biological perspective, the mechanisms by which IDH 1/2 mutations confer a better prognosis remain to be elucidated.

IDH 1/2 mutations are invariably missense and monoallelic. In gliomas, more than 90% of mutations involve IDH1 at the arginine residue at the enzymatic active site (R132H) 7, 12, 37, 101. This observation is in contrast to other tumors such as AML where IDH1 and IDH2 mutations occur at equal frequency. This finding suggests an important role for wild‐type IDH1 in glial biology. The high frequency of IDH1 R132H mutations can be leveraged in diagnostic neuropathology using an antibody that specifically detects this mutation 14. Immunohistochemistry with this antibody has been proven very useful in readily detecting the mutation as a molecular surrogate and in histopathologic diagnostic challenges such as identifying single infiltrating tumor cells in limited biopsy material, differentiating recurrent tumor from reactive atypia and separating gangliogliomas from infiltrating astrocytomas 12, 13, 38. Other IDH1 mutations are rare but still involve the R132 residue where the arginine residue is replaced by other amino acids (such as C, G, S, L, V) 25. While IDH2 mutations are rare in gliomas, when they occur they also affect the catalytic arginine sites of the enzyme: R172 and R140 25.

2‐HG is a Metabolite Produced in IDH 1/2 Mutant Tumors and 2‐HG Aciduria

Wild‐type IDH proteins (IDH1–3) are enzymes closely related to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and catalyze the conversion of isocitrate to α‐ketoglutarate (α‐KG, also referred to as 2‐oxoglutarate). IDH2 and IDH3 are mitochondrial enzymes, while IDH1 is mainly cytosolic. All three isoforms of IDH are critical for the generation of reducing equivalents. IDH3 is a heterotetrameric complex (formed by two α, one β and one γ subunits) that uses NAD+ as a cofactor to generate NADH and this mitochondrial reaction is irreversible 103. On the other hand, both IDH2 and IDH1 are homodimers and use NADP+ as a cofactor to produce NADPH 97. Monoallelic IDH1 mutations were initially hypothesized to promote oncogenesis through loss‐of‐function in enzymatic capacity to generate α‐KG from isocitrate by the mutant allele along with dominant negative activity against the wild‐type allele 104. Subsequent studies have revealed a gain‐of‐function activity of the mutant enzyme that uses α‐KG as a substrate along with NADPH consumption to generate the metabolite (D)‐2‐HG in millimolar concentrations 26, 36, 95. In proliferating cells in vitro, α‐KG and subsequently (D)‐2‐HG is primarily derived from the amino acid glutamine, with smaller contributions from glucose carbons 26, 93, 97.

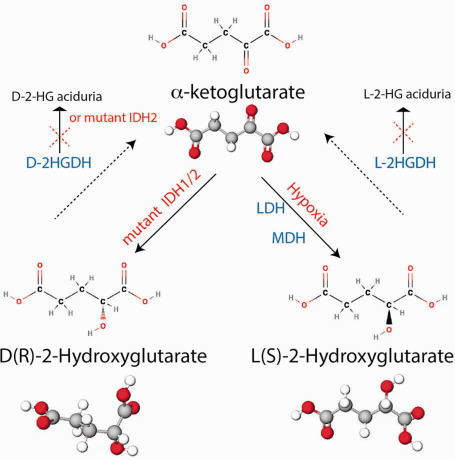

2‐HG is a metabolite that has been studied in the context of inborn metabolic disorders termed 2‐HG acidurias described initially in 1980 15, 28. 2‐HG is made in low concentrations in normal cells and can exist in two enantiomeric isoforms: D (also termed R)‐2‐HG and L (also termed S)‐2‐HG (inspiring the title of this article) 46 (Figure 1). These chiral forms of 2‐HG are metabolized by dehydrogenases termed D‐2‐hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (D‐2‐HGDH) and L‐2‐hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (L‐2‐HGDH) (Figure 1). Germline loss‐of‐function mutations of either of these enzymes cause impaired 2‐HG metabolism. This leads to accumulation of the metabolite resulting in D‐ or L‐2‐HG aciduria, respectively 83, 85. Combined D‐2‐ and L‐2‐hydroxyglutaric aciduria is a rare disorder and is characterized by mutations in SLC25A1, the mitochondrial citrate transporter 65.

Figure 1.

Enantiomers of 2‐hydroxyglutarate (2‐HG). In normal cells, D(R)‐2‐HG is produced at very low levels and is metabolized back to α‐ketoglutarate (α‐KG) by D‐2‐HG dehydrogenase (D‐2‐HGDH). D‐2‐HGDH loss‐of‐function mutations and IDH2 gain‐of‐function mutations result in D‐2‐HG aciduria. In cancers, D(R)‐2‐HG is generated in high concentrations by the activity of mutant IDH 1/2. L(S)‐2‐HG is synthesized at very low levels in normal cells and is metabolized back to α‐KG by L‐2‐HG dehydrogenase (L‐2‐HGDH). L‐2‐HGDH loss‐of‐function mutations result in L‐2‐HG aciduria. In tumor hypoxic environments, both lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) can convert α‐KG to L‐2‐HG.

Intriguingly, D‐2‐HG aciduria patients do not show brain tumors (with the caveat that many of these patients have relatively shorter lifespan) but can exhibit developmental delays, seizures, enlarged ventricles, benign CNS (central nervous system) cysts and multifocal cerebral white matter abnormalities 46, 91. D‐2‐HGDH loss‐of‐function heterozygous mutations are also noted in a small subset of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma, resulting in modest elevations on D‐2‐HG 51. In addition to D‐2‐HGDH loss‐of‐function mutations, IDH2 gain‐of‐function mutations, similar to those seen in AML, involving the R140 residue are also noted in a fraction of D‐2‐HG aciduria patients and can be modeled in mice 1, 45. The absence of an association of brains tumors in humans and mouse models of D‐2‐HG aciduria suggests that the pathogenesis of tumors bearing IDH 1/2 mutations may be multifactorial.

IDH 1/2 Mutations and D‐2‐HG in Glioma Oncogenesis

IDH 1/2 mutations and D‐2‐HG impact oncogenesis by impairing cell differentiation (Figure 2). Immortalized astrocytes, neuronal stem cells, erythroleukemia cell lines, liver progenitor cells and chondrosarcoma cell culture models expressing mutant forms of IDH show arrested cell differentiation 44, 54, 56, 57, 76, 90. Further, cell permeable forms of D‐2‐HG negatively impact differentiation in glioma and leukemia cell models 54, 56. This suppression of differentiation, when coupled with a second genetic hit, is hypothesized to drive glioma pathogenesis (Figure 2). The second hit hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that the IDH1 R132H mutation alone is insufficient to form gliomas in mouse models in vivo 77. It is speculated that IDH 1/2 mutations suppress the ability of early glial precursors to differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes or astrocytes. When this cell additionally accumulates p53 and ATRX mutations, it is thought to give rise to astrocytic tumors (Figure 2). On the other hand, when this IDH 1/2 mutant cell acquires 1p/19q deletions (corresponding to CIC and FUBP1 alterations) along with TERT promoter mutations, it is thought to give rise to oligodendrogliomas (Figure 2). Interestingly, mutant CIC cooperates with IDH1 mutations to increase levels of D‐2‐HG 20. Finally, the association of IDH 1/2 mutations with astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas supports this hypothesis 37, 49, 98. This model has led to the suggestion that IDH 1/2 mutations occur as an early event in gliomagenesis.

Figure 2.

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1/2 mutation is an early event in glioma genesis. IDH 1/2 mutations are thought to occur as an early event in glioma biology in early glial progenitors. D‐2‐hydroxyglutarate (D‐2‐HG) is thought to impair cell differentiation in these cells as a result of histone and DNA hypermethylation (G‐CIMP). When these cells acquire 1p/19q co‐deletions (corresponding to FUBP1 and CIC alterations) and TERT promoter mutations, they give rise to oligodendrogliomas. When these cells accumulate p53 and ATRX mutations, they are thought to develop into astrocytomas and secondary glioblastomas (GBM) on acquiring additional mutations.

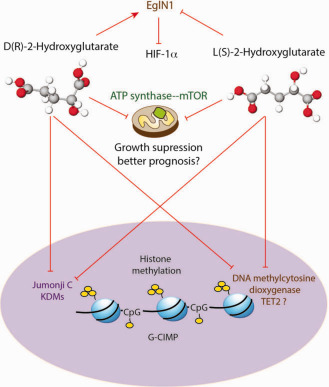

IDH 1/2 mutations are thought to impair cell differentiation by directly reprogramming the epigenetic state of the cell by influencing DNA and histone methylation (Figures 2 and 3). Prior analyses of DNA methylation in GBM revealed a subset of tumors that displayed widespread DNA hypermethylation across the genome. These tumors are referred to as the glioma‐associated‐CpG island hypermethylator phenotype (G‐CIMP) 66. Similar to IDH mutant tumors, these gliomas have better prognostic outcomes than non‐G‐CIMP tumors 66. Moreover, G‐CIMP is strongly associated with IDH 1/2 mutations in both GBM and intermediate‐grade gliomas 23, 27, 48, 66, 90. Expression of IDH1 R132H mutation in immortalized astrocytes and other cell lines results in DNA hypermethylation similar to that seen in G‐CIMP 27, 57, 90.

Figure 3.

D‐2‐hydroxyglutarate (D‐2‐HG) and L‐2‐hydroxyglutarate (L‐2‐HG) have similar and differential effects. D‐2‐HG is thought to potentiate eglin1, while L‐2‐HG antagonizes eglin1, leading to HIF‐1α stabilization. Both D‐ and L‐2‐HG can inhibit DNA and histone demethylases, resulting in histone and DNA hypermethylation (G‐CIMP phenotype). Both enantiomers also inhibit ATP synthase and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibit growth of glioma cells and may contribute to better prognosis seen in IDH1/2 gliomas.

The mechanism by which IDH 1/2 mutations reprogram DNA methylation is directly linked to the structure of 2‐HG. Both D‐ and L‐isoforms of 2‐HG are similar in structure to α‐KG (Figure 3). The metabolite α‐KG along with oxygen and iron are critical cofactors for reactions driven by a family of enzymes termed α‐KG‐dependent dioxygenases. These enzymes regulate a number of cellular reactions, including DNA methylation, histone methylation, carnitine synthesis, hypoxia sensing and collagen modifications 52. The structural similarity of D‐ and L‐2‐HG to α‐KG is thought to result in a competitive inhibition of α‐KG‐dependent enzymatic reactions 22, 100. Interestingly, D‐2‐HG is made at very low levels under normal conditions and is considered a by‐product of cellular metabolism (generated by the enzyme hydroxyacid–oxoacid transhydrogenase) 86. D‐2‐HG accumulation is prevented by its conversion to α‐KG by D‐2‐HGDH (Figure 2) 46. Activity of D‐2‐HGDH can increase α‐KG levels directly and indirectly by enhancing IDH2 function in an unknown manner 51. Elevated α‐KG concentrations drive demethylation of histones and DNA by potentiating the function of α‐KG‐dependent demethylases 51. In IDH mutant tumors, the concentration of D‐2‐HG produced from the activity of mutant IDH 1/2 is so high that it overwhelms the activity of D‐2‐HGDH, resulting in accumulation of D‐2‐HG and inhibiting the function of these α‐KG‐dependent enzymes resulting in DNA and histone hypermethylation 22, 55, 100.

The strongest support for this hypothesis in relation to DNA methylation comes from the leukemias where IDH 1/2 mutations and loss‐of‐function mutations in the DNA methylating enzyme TET2 are mutually exclusive 32. TET2 is an α‐KG‐dependent DNA methylating enzyme (methyl cytosine dioxygenase) that hydroxylates 5‐methylcytosine to 5‐hydroxylmethycytosine 88. Further, TET2 knockdown in leukemia cells blocks differentiation in a fashion similar to IDH2 mutations 54. While TET2 promoter methylation is seen in a small fraction of IDH 1/2 wild‐type low‐grade gliomas, no mutations in the TET family of proteins are reported in gliomas 43. Further, no significant relationship was observed between IDH 1/2 mutations and decreased 5‐hydroxylmethycytosine in glioma samples, suggesting that this effect is not driven by TET2 inhibition 41, 63, 68. The mechanisms of how IDH 1/2 mutations and D‐2‐HG reprogram DNA methylation in gliomas and cause the G‐CIMP phenotype require further elucidation.

Similar to its effects on inhibiting DNA methylating enzymes, D‐2‐HG can also inhibit histone‐demethylating enzymes resulting in histone hypermethylation 22, 55, 100 (Figure 3). The jumonji C family of histone methyltransferases depend on α‐KG for their activity 22. Cell permeable forms of D‐2‐HG can increase histone methylation marks in adipocytes 55. Similarly, IDH mutations expressed in various cell lines and IDH 1/2 mutant oligodendrogliomas induce histone hypermethylation as evidenced by increased trimethylation of histone marks such as H3K9, H3K27 and H3K36 27, 55, 90, 92, 100. Together, DNA and histone hypermethylation affect the expression of many genes and are thought to contribute to suppressing cell differentiation.

D‐2‐HG also impacts the function of other α‐KG‐dependent dioxygenases. While conditional knock‐in of IDH1 R132H in mice does not induce tumor formation, it does alter collagen maturation by blocking prolyl‐hydroxylation. This abnormal maturation leads to defective vasculature and cerebral hemorrhage in the brain 77. Interestingly, effects on prolyl‐hydroxylation may be context‐dependent. EglN1 is an α‐KG and oxygen‐dependent prolyl hydroxylase that enables HIF1‐α degradation by the VHL complex. In hypoxia, EglN1 enzymatic activity is decreased, resulting in HIF1‐α stabilization. Instead of blocking EGln1 activity, D‐2‐HG is thought to potentiate EglN1 activity, resulting in enhanced proliferation of immortalized human astrocytes in soft agar in an undefined manner (Figure 3) 44. Along similar lines, both α‐KG and 2‐HG (both D‐ and L‐isoforms) can extend the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans by inhibiting ATP synthase. Inhibition of ATP synthase is thought to lower mitochondrial respiration and attenuate mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, resulting in lowered tumor cell growth and viability (Figure 3) 19, 33. These findings could potentially relate to the overall better survival outcomes in IDH 1/2 mutant glioma patients compared with wild‐type tumors. In addition to influencing α‐KG‐dependent cellular functions, D‐2‐HG can also inhibit the activity of cytochrome c oxidase in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This inhibition causes increased apoptosis in IDH2 mutant leukemic cell lines and is of potential therapeutic use 16. Thus, D‐2‐HG can affect distinct cellular phenomena, many of which need to be further defined in IDH 1/2 mutant gliomas.

Tumor Microenvironment, L‐2‐HG and Its Role in Oncogenesis

L‐2‐HG acidurias are characterized by loss‐of‐function mutations in L‐2‐HGDH and subsequent L‐2‐HG accumulation. Patients with this disorder show delayed development and seizures similar to D‐2‐HG acidurias. Additionally, cerebellar dysfunction, dystonia and spasticity, tremors, and white matter changes in the cerebrum, cerebellum and basal ganglia can be observed 45. In contrast to D‐2‐HG‐acidurias, astrocytomas, bone tumors, gliomatosis cerebri and Wilm's tumors have been described as rare features of L‐2‐HG aciduria patients 45, 53. Further, renal cancers with VHL mutations show decreased expression of L‐2‐HGDH, resulting in elevated levels of L‐2‐HG 80. Together, these observations suggest that L‐2‐HG may play a role in oncogenesis. D‐2‐HG is produced by IDH 1/2 mutations, but how is L‐2‐HG synthesized and how does this affect tumor pathogenesis? Recent studies suggest that hypoxic tumor microenvironments result in increased L‐2‐HG production from α‐KG accompanied by the consumption of NADH 40, 67. This phenomenon was not dependent on the activity of wild‐type IDH 1/2 enzymes but was mediated in a context‐dependent manner to different degrees by the enzymes malate dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase (Figure 3) 40, 67.

As discussed previously, decreased EglN1 (α‐KG‐dependent prolyl hydroxylase) enzymatic activity results in HIF1‐α stabilization. While D‐2‐HG potentiates EglN1 activity, L‐2‐HG inhibits EglN in vitro and promotes HIF‐1α accumulation (Figure 3) 44, 54. This model would suggest a reciprocal feedback mechanism in which hypoxic generation of L‐2‐HG stabilizes HIF‐1α, further promoting hypoxia. However, L‐2‐HG synthesis was independent of the effects of HIF‐1α, suggesting that L‐2‐HG production was driven by other mechanisms 67. Hypoxia results in increased cytosolic and mitochondrial NADH production caused by redirection of glucose metabolism to anaerobic glycolysis 78. Generation of L‐2‐HG is thought to be a cellular adaptive response to consume these excessive reducing equivalents. L‐2‐HG production was also directly related to α‐KG substrate availability. In hypoxia, glutamine metabolism is reprogrammed such that glutamine becomes the main TCA cycle substrate to generate α‐KG 60, 62, 99. In glioblastoma cell lines, glutamine‐generated α‐KG was the main substrate for L‐2‐HG synthesis 40, although glucose‐derived α‐KG also contributed to L‐2‐HG production in other cell lines 67. Further, L‐2‐HG accumulation in hypoxia reduced glycolytic flux through a negative feedback loop, perhaps to limit additional NADH synthesis via glycolysis 67. These data suggest that L‐2‐HG production may be an adaptive response to maintain redox balance in hypoxic tumor cells.

While the effects of D‐2‐HG and L‐2‐HG on EglN1 are thought to be opposed, both metabolites inhibit α‐KG‐dependent dioxygenases including DNA and histone demethylases (Figure 3). Intriguingly, L‐2‐HG is thought to be a more potent inhibitor of enzymes like TET2 44, 100. In glioma cells, L‐2‐HG in hypoxia caused increased H3K9me3, depending on inhibition of the activity of the histone demethylase KDM4C 40. This effect corresponded to increased H3K9me3 in hypoxic niches in IDH 1/2 wild‐type GBM tumor samples. Similarly, L‐2‐HG accumulation in VHL‐mutated renal cancer causes increased DNA and histone methylation 80. Overall, these data suggest that L‐2‐HG mediates epigenetic changes in hypoxic tumor niches in IDH wild‐type gliomas resulting in tumor heterogeneity.

Imaging of 2‐HG In Vivo

The accumulation of intracellular D‐2‐HG to millimolar concentrations in IDH1/2‐mutated tumors can be leveraged to image these tumors in vivo and thus non‐invasively determine the IDH mutational status. Several imaging modalities including conventional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and hyperpolarized 13C MRS can detect 2‐HG in vivo. Because IDH wild‐type tumors and normal tissues do not accumulate appreciable amounts of D‐ or L‐2‐HG under normal conditions, spectroscopic detection has the possibility to spatially discriminate tumor from normal tissue based on altered biochemistry. In the past several years, interest in D‐2‐HG imaging has increased dramatically with a focus on its potential as a biomarker for IDH 1/2 mutations, a potential early marker for treatment response and as a tool for distinguishing tumor progression from pseudoprogression in IDH 1/2 mutated gliomas.

Conventional MRS was introduced in the 1970s as a method of defining the biochemical environment of tissues 82. A technical description of MRS theory and methodology is beyond the scope of this review, but in brief, the technique provides a proton spectrum for individual voxels that allows for the detection and quantification of major neurometabolites, including N‐acetylaspartate (NAA), choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), alanine (Ala) and lactate. While many nuclei can be monitored by spectroscopy, proton MRS is used clinically because of the high abundance of protons, their favorable gyromagnetic ratio and the ability to perform proton MRS without additional hardware beyond what is typically used in a clinical scanner 82. Most brain tumors have elevated Cho and decreased NAA compared with normal brain and therefore a common clinical use of MRS is to assess the NAA/Cho ratio to distinguish glioma from normal brain or treatment effects 82.

The initial discovery that L‐2‐HG could be monitored by MRS was made in the early 2000s when patients with congenital L‐2‐HG aciduria were found to have an abnormal singlet spectral peak between 2.25 and 2.7 ppm in all voxels of the brain analyzed 34, 79. Subsequent studies have shown that the MRS spectra of both D‐ and L‐enantiomers are identical 84. Therefore, once the oncogenic IDH1/2 mutations were shown to produce D‐2‐HG, there was tremendous interest to apply MRS techniques to image IDH1/2‐mutated tumors. Initial publications demonstrating MRS detection of D‐2‐HG in IDH1‐mutated brain tumors came in 2012 from the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) 21 and from the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) 4. These groups both noted that one of the main difficulties in the MRS detection of D‐2‐HG was its spectral proximity to nearby glutamine/glutamate and NAA resonance peaks 8. The MGH group overcame this difficulty by using two‐dimensional correlation spectroscopy, while the UTSW group optimized echo time and used J‐difference spectroscopy to minimize the signal from overlapping metabolites. Both groups demonstrated that MRS detection of D‐2‐HG occurred only in patients with IDH1‐mutated gliomas and found concentrations of 1.7–8.9 mM of D‐2‐HG. The 100% specificity associated with these advanced MRS techniques is a major improvement over standard MRS techniques for D‐2‐HG detection, which had false‐positive rates near 20% 72.

The clinical use of MRS to detect D‐2‐HG is in its infancy, but possible opportunities abound. The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center group has recently presented their results of incorporating D‐2‐HG MRS into standard imaging for glioma patients 24. D‐2‐HG MRS was performed on 107 consecutive grade II–IV glioma patients, 75% of which contained mutated IDH 1/2. 2‐HG MRS was negative in all patients with wild‐type IDH and all those with mutant IDH 1/2 tumors with volume less than 8 cm3. Approximately 35% of patients with mutant IDH 1/2 had positive D‐2‐HG MRS scans. Intriguingly, results from a subset of patients who received multiple scans while undergoing active treatment suggested that a drop in D‐2‐HG levels is associated with a treatment response. While the specificity of D‐2‐HG MRS is excellent, increased sensitivity is needed, especially for smaller tumors. Furthermore, applying this technique as a biomarker for treatment response or as a marker for early progression will require much additional study.

An alternative means of imaging D‐2‐HG is by using hyperpolarized carbon 13 (13C) MRS rather than proton spectroscopy. Because MRS visualizes only paramagnetic atoms, this technique detects only 13C rather than the more abundant 12C. Typically, 13C is difficult to image by spectroscopy because of its low natural abundance (approximately 1%) and unfavorable gyromagnetic ratio, both of which result in a nearly insurmountably low signal‐to‐noise ratio 47. An increasingly utilized technology to overcome these limitations is hyperpolarized 13C MRS. In this technique, a 13C‐enriched metabolic tracer is obtained to interrogate the metabolic pathway of interest (eg, pyruvate to investigate lactate dehydrogenase or α‐ketoglutarate to investigate the TCA cycle). Immediately prior to tracer administration and scanning, the 13C tracer is “hyperpolarized” by exposing it to microwaves and unpaired electron donors while at extremely low temperatures in a technique known as dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) 6. This process alters the Boltzmann distribution of 13C and can increase sensitivity by more than 10 000‐fold. Because 13C only remains hyperpolarized for a very short time, the tracer is then immediately infused into the patient where it is detected by MRS. More importantly, the conversion of the administered metabolite into its downstream products can be measured by simultaneously measuring the disappearance of 13C in the administered metabolite and the appearance of 13C into potential products. Therefore, unlike conventional MRS, hyperpolarized 13C MRS allows for the detection of dynamic metabolic fluxes in real time 64.

The mutant IDH 1/2‐catalyzed conversion of α‐KG to D‐2‐HG has recently been imaged using hyperpolarized 13C MRS 18. In this study, α‐KG tracer was synthesized with 13C at the first carbon position ([1‐13C] α‐KG). After hyperpolarization, this tracer was administered to rats bearing either IDH1 WT or mutant GBM xenografts and conversion of [1‐13C] α‐KG into [1‐13C] D‐2‐HG was seen only in the IDH1 mutant tumors 18. Interestingly, the conversion of α‐KG into glutamate is catalyzed by branched‐chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1) and the activity of BCAT1 is severely diminished in IDH 1‐mutated gliomas 89. Therefore, combined analysis of the formation of hyperpolarized [1‐13C] D‐2‐HG and hyperpolarized [1‐13C] glutamate from a single tracer ([1‐13C] α‐KG) could give more robust information about the IDH 1/2 mutational status of a tumor 89. While these observations are yet to be translated to the clinic, potential applications abound. Changes in the flux through individual metabolic pathways can indicate a response to chemotherapy in as little as 24 h after treatment initiation 70. Therefore, early changes in the observed conversion of α‐KG to D‐2‐HG could reveal which patients with IDH1/2‐mutated gliomas are receiving a benefit from chemotherapy.

Inhibition of D‐2‐HG as a Therapeutic Target in IDH 1/2 Mutant Gliomas

Pharmacologic inhibitors of mutant IDH1 and IDH2 have been recently synthesized and show great promise in cell lines, IDH 1/2 tumor animal models and AML patients 17, 42, 54, 73, 74, 94. Treatment of oligodendroglioma cell lines bearing 1p/19q co‐deletions and IDH1 R132H mutations with IDH1 mutant specific inhibitors showed significant decreases in D‐2‐HG production. This was accompanied by modest growth inhibition in subcutaneous glioma models in vivo. Importantly, the inhibitor resulted in demethylation of histone H3K9me3 and promoted the expression of genes associated with glial differentiation, suggesting that its therapeutic effects arose from reversing D‐2‐HG‐mediated hypermethylation. Intriguingly, DNA methylation did not appreciably decrease after treatment 74. Treatment of patient‐derived AML cells with a mutant IDH2 inhibitor induced differentiation in vitro with early reversal of increased histone methylation, but in contrast to glioma, models showed a slower reversal of DNA hypermethylation 42, 94. Early data from a clinical trial in IDH mutant human subjects with AML show promising results 5. Other approaches target the metabolic pathway of D‐2‐HG generation. As D‐2‐HG is mainly derived from glutamine, inhibition of glutaminase, which metabolizes glutamine to glutamate, reduces D‐2‐HG production, cell growth and histone hypermethylation of IDH1‐mutant cells 30. While these approaches show great promise, blood–brain barrier permeability issues poses a challenge that needs to be overcome for effective treatment in IDH 1/2 mutant gliomas.

Summary

2‐HG can exist as two chiral isoforms: D‐2‐HG and L‐2‐HG. Both molecules are produced in negligible quantities in normal cells as by‐products of metabolism and are degraded by enantiomer‐specific dehydrogenases. D‐2‐HG accumulates in D‐2‐HG aciduria as a result of the loss‐of‐function mutations in D‐2‐HGDH and gain‐of‐function IDH2 mutations. L‐2‐HG is elevated in L‐2‐HG aciduria as a result of the loss‐of‐function mutations in L‐2‐HGDH. In cancers, D‐2‐HG is generated from α‐KG by gain‐of‐function IDH 1/2 mutations. IDH 1/2 wild‐type tumors synthesize L‐2‐HG from α‐KG by the enzymes MDH and LDH in hypoxia, albeit at lower concentrations. Both isoforms of 2‐HG are similar in structure to α‐KG, resulting in inhibition of enzymes like ATP synthase and α‐KG‐dependent dioxygenases such as histone and DNA demethylases (L‐2‐HG is thought to be more potent than D‐2‐HG). They can also differ in function; while D‐2‐HG potentiates the activity of Egln1 (a prolyl hydroxylase enzyme that destabilizes HIF‐1α), L‐2‐HG is thought to inhibit it. The production of L‐2‐HG is thought to be an adaptive response to help adapt cells to hypoxic redox changes. Thus, both isoforms of 2‐HG are implicated in cancers and can impact the epigenetic state of the tumors. Because of its high concentrations, D‐2‐HG can be detected in vivo in IDH 1/2 mutant gliomas using MRS and hyperpolarized 13C MRS imaging techniques. Finally, lowering D‐2‐HG using IDH 1/2 mutation‐specific small‐molecule inhibitors shows great promise in treating these patients.

References

- 1. Akbay EA, Moslehi J, Christensen CL, Saha S, Tchaicha JH, Ramkissoon SH et al (2014) D‐2‐hydroxyglutarate produced by mutant IDH2 causes cardiomyopathy and neurodegeneration in mice. Genes Dev 28:479–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S, Halai D, Berisha F et al (2011) IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol 224:334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amary MF, Damato S, Halai D, Eskandarpour M, Berisha F, Bonar F et al (2011) Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome are caused by somatic mosaic mutations of IDH1 and IDH2. Nat Genet 43:1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andronesi OC, Kim G, Gerstner E, Batchelor T, Tzika AA, Fantin VR et al (2012) Detection of 2‐hydroxyglutarate in IDH‐mutated glioma patients by spectral‐editing and 2D correlation magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Sci Transl Med 4:116ra4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anonymous (2015) IDH1 inhibitor shows promising early results. Cancer Discov 5:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ardenkjaer‐Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH et al (2003) Increase in signal‐to‐noise ratio of >10,000 times in liquid‐state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:10158–10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, Korshunov A, Hartmann C, von Deimling A (2008) Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol 116:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertolino N, Marchionni C, Ghielmetti F, Burns B, Finocchiaro G, Anghileri E et al (2014) Accuracy of 2‐hydroxyglutarate quantification by short‐echo proton‐MRS at 3 T: a phantom study. Phys Med 30:702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borger DR, Tanabe KK, Fan KC, Lopez HU, Fantin VR, Straley KS et al (2012) Frequent mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 and IDH2 in cholangiocarcinoma identified through broad‐based tumor genotyping. Oncologist 17:72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cairns RA, Iqbal J, Lemonnier F, Kucuk C, de Leval L, Jais JP et al (2012) IDH2 mutations are frequent in angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma. Blood 119:1901–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network , Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD, Yung WK, Salama SR et al (2015) Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower‐grade gliomas. N Engl J Med 372:2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Capper D, Zentgraf H, Balss J, Hartmann C, von Deimling A (2009) Monoclonal antibody specific for IDH1 R132H mutation. Acta Neuropathol 118:599–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Capper D, Sahm F, Hartmann C, Meyermann R, von Deimling A, Schittenhelm J (2010) Application of mutant IDH1 antibody to differentiate diffuse glioma from nonneoplastic central nervous system lesions and therapy‐induced changes. Am J Surg Pathol 34:1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Capper D, Weissert S, Balss J, Habel A, Meyer J, Jager D et al (2010) Characterization of R132H mutation‐specific IDH1 antibody binding in brain tumors. Brain Pathol 20:245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chalmers RA, Lawson AM, Watts RW, Tavill AS, Kamerling JP, Hey E, Ogilvie D (1980) D‐2‐hydroxyglutaric aciduria: case report and biochemical studies. J Inherit Metab Dis 3:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan SM, Thomas D, Corces‐Zimmerman MR, Xavy S, Rastogi S, Hong WJ et al (2015) Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations induce BCL‐2 dependence in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med 21:178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaturvedi A, Araujo Cruz MM, Jyotsana N, Sharma A, Yun H, Gorlich K et al (2013) Mutant IDH1 promotes leukemogenesis in vivo and can be specifically targeted in human AML. Blood 122:2877–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chaumeil MM, Larson PE, Yoshihara HA, Danforth OM, Vigneron DB, Nelson SJ et al (2013) Non‐invasive in vivo assessment of IDH1 mutational status in glioma. Nat Commun 4:2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chin RM, Fu X, Pai MY, Vergnes L, Hwang H, Deng G et al (2014) The metabolite alpha‐ketoglutarate extends lifespan by inhibiting ATP synthase and TOR. Nature 510:397–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chittaranjan S, Chan S, Yang C, Yang KC, Chen V, Moradian A et al (2014) Mutations in CIC and IDH1 cooperatively regulate 2‐hydroxyglutarate levels and cell clonogenicity. Oncotarget 5:7960–7979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi C, Ganji SK, DeBerardinis RJ, Hatanpaa KJ, Rakheja D, Kovacs Z et al (2012) 2‐Hydroxyglutarate detection by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in IDH‐mutated patients with gliomas. Nat Med 18:624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chowdhury R, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, Hillringhaus L, Bagg EA, Rose NR et al (2011) The oncometabolite 2‐hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases. EMBO Rep 12:463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Christensen BC, Smith AA, Zheng S, Koestler DC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ et al (2011) DNA methylation, isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation, and survival in glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de la Fuente MI, Young R, Rubel J, Tisnado J, Briggs S, Holodny AI et al (2015) Feasibility of 2‐hydroxyglutarate 1HMR spectroscopy for routine clinical glioma imaging. In: Proceedings of the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, April 18–22, 2015, Philadelphia, PA: AACR; Cancer Res 2015;75(15 Suppl): Abstract #1498.

- 25. Dang L, Jin S, Su SM (2010) IDH mutations in glioma and acute myeloid leukemia. Trends Mol Med 16:387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM et al (2010) Cancer‐associated IDH1 mutations produce 2‐hydroxyglutarate. Nature 465:966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duncan CG, Barwick BG, Jin G, Rago C, Kapoor‐Vazirani P, Powell DR et al (2012) A heterozygous IDH1R132H/WT mutation induces genome‐wide alterations in DNA methylation. Genome Res 22:2339–2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Duran M, Kamerling JP, Bakker HD, van Gennip AH, Wadman SK (1980) L‐2‐Hydroxyglutaric aciduria: an inborn error of metabolism? J Inherit Metab Dis 3:109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eckel‐Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H et al (2015) Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N Engl J Med 372:2499–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elhammali A, Ippolito JE, Collins L, Crowley J, Marasa J, Piwnica‐Worms D (2014) A high‐throughput fluorimetric assay for 2‐hydroxyglutarate identifies Zaprinast as a glutaminase inhibitor. Cancer Discov 4:828–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellison DW (2015) Multiple molecular data sets and the classification of adult diffuse gliomas. N Engl J Med 372:2555–2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Figueroa ME, Abdel‐Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A et al (2010) Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell 18:553–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fu X, Chin RM, Vergnes L, Hwang H, Deng G, Xing Y et al (2015) 2‐Hydroxyglutarate inhibits ATP synthase and mTOR signaling. Cell Metab 22:508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goffette SM, Duprez TP, Nassogne MC, Vincent MF, Jakobs C, Sindic CJ (2006) L‐2‐Hydroxyglutaric aciduria: clinical, genetic, and brain MRI characteristics in two adult sisters. Eur J Neurol 13:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gorovets D, Kannan K, Shen RL, Kastenhuber ER, Islamdoust N, Campos C et al (2012) IDH mutation and neuroglial developmental features define clinically distinct subclasses of lower grade diffuse astrocytic glioma. Clin Cancer Res 18:2490–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gross S, Cairns RA, Minden MD, Driggers EM, Bittinger MA, Jang HG et al (2010) Cancer‐associated metabolite 2‐hydroxyglutarate accumulates in acute myelogenous leukemia with isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations. J Exp Med 207:339–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hartmann C, Meyer J, Balss J, Capper D, Mueller W, Christians A et al (2009) Type and frequency of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are related to astrocytic and oligodendroglial differentiation and age: a study of 1,010 diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 118:469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Yeaney G, Camelo‐Piragua S, Venneti S, Louis DN et al (2011) Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 analysis differentiates gangliogliomas from infiltrative gliomas. Brain Pathol 21:564–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, Mokhtari K, Guillevin R, Laffaire J et al (2010) IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in low‐grade gliomas. Neurology 75:1560–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Intlekofer AM, Dematteo RG, Venneti S, Finley LW, Lu C, Judkins AR et al (2015) Hypoxia induces production of L‐2‐hydroxyglutarate. Cell Metab 4:304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jin SG, Jiang Y, Qiu R, Rauch TA, Wang Y, Schackert G et al (2011) 5‐Hydroxymethylcytosine is strongly depleted in human cancers but its levels do not correlate with IDH1 mutations. Cancer Res 71:7360–7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kernytsky A, Wang F, Hansen E, Schalm S, Straley K, Gliser C et al (2015) IDH2 mutation‐induced histone and DNA hypermethylation is progressively reversed by small‐molecule inhibition. Blood 125:296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim YH, Pierscianek D, Mittelbronn M, Vital A, Mariani L, Hasselblatt M, Ohgaki H (2011) TET2 promoter methylation in low‐grade diffuse gliomas lacking IDH1/2 mutations. J Clin Pathol 64:850–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koivunen P, Lee S, Duncan CG, Lopez G, Lu G, Ramkissoon S et al (2012) Transformation by the (R)‐enantiomer of 2‐hydroxyglutarate linked to EGLN activation. Nature 483:484–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kranendijk M, Struys EA, van Schaftingen E, Gibson KM, Kanhai WA, van der Knaap MS et al (2010) IDH2 mutations in patients with D‐2‐hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Science 330:336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kranendijk M, Struys EA, Salomons GS, Van der Knaap MS, Jakobs C (2012) Progress in understanding 2‐hydroxyglutaric acidurias. J Inherit Metab Dis 35:571–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kurhanewicz J, Bok R, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB (2008) Current and potential applications of clinical (13)C MR spectroscopy. J Nucl Med 49:341–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Laffaire J, Everhard S, Idbaih A, Criniere E, Marie Y, de Reynies A et al (2011) Methylation profiling identifies 2 groups of gliomas according to their tumorigenesis. Neuro‐Oncol 13:84–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lai A, Kharbanda S, Pope WB, Tran A, Solis OE, Peale F et al (2011) Evidence for sequenced molecular evolution of IDH1 mutant glioblastoma from a distinct cell of origin. J Clin Oncol 29:4482–4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leu S, von Felten S, Frank S, Vassella E, Vajtai I, Taylor E et al (2013) IDH/MGMT‐driven molecular classification of low‐grade glioma is a strong predictor for long‐term survival. Neuro‐Oncol 15:469–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lin AP, Abbas S, Kim SW, Ortega M, Bouamar H, Escobedo Y et al (2015) D2HGDH regulates alpha‐ketoglutarate levels and dioxygenase function by modulating IDH2. Nat Commun 6:7768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Loenarz C, Schofield CJ (2008) Expanding chemical biology of 2‐oxoglutarate oxygenases. Nat Chem Biol 4:152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. London F, Jeanjean A (2015) Gliomatosis cerebri in L‐2‐hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Acta Neurol Belg 2015 May 22. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Losman JA, Looper RE, Koivunen P, Lee S, Schneider RK, McMahon C et al (2013) (R)‐2‐hydroxyglutarate is sufficient to promote leukemogenesis and its effects are reversible. Science 339:1621–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu C, Thompson CB (2012) Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell Metab 16:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, Rohle D, Turcan S, Abdel‐Wahab O et al (2012) IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature 483:474–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lu C, Venneti S, Akalin A, Fang F, Ward PS, Dematteo RG et al (2013) Induction of sarcomas by mutant IDH2. Genes Dev 27:1986–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Chen K et al (2009) Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med 361:1058–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mellai M, Piazzi A, Caldera V, Monzeglio O, Cassoni P, Valente G, Schiffer D (2011) IDH1 and IDH2 mutations, immunohistochemistry and associations in a series of brain tumors. J Neurooncol 105:345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K et al (2011) Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature 481:380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Metellus P, Coulibaly B, Colin C, de Paula AM, Vasiljevic A, Taieb D et al (2010) Absence of IDH mutation identifies a novel radiologic and molecular subtype of WHO grade II gliomas with dismal prognosis. Acta Neuropathol 120:719–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, Cheng T et al (2011) Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature 481:385–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Muller T, Gessi M, Waha A, Isselstein LJ, Luxen D, Freihoff D et al (2012) Nuclear exclusion of TET1 is associated with loss of 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine in IDH1 wild‐type gliomas. Am J Pathol 181:675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nelson SJ, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Larson PE, Harzstark AL, Ferrone M et al (2013) Metabolic imaging of patients with prostate cancer using hyperpolarized [1‐(1)(3)C]pyruvate. Sci Transl Med 5:198ra08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nota B, Struys EA, Pop A, Jansen EE, Fernandez Ojeda MR, Kanhai WA et al (2013) Deficiency in SLC25A1, encoding the mitochondrial citrate carrier, causes combined D‐2‐ and L‐2‐hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Am J Hum Genet 92:627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP et al (2010) Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell 17:510–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Oldham WM, Clish CB, Yang Y, Loscalzo J (2015) Hypoxia‐mediated increases in l‐2‐hydroxyglutarate coordinate the metabolic response to reductive stress. Cell Metab 22:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Orr BA, Haffner MC, Nelson WG, Yegnasubramanian S, Eberhart CG (2012) Decreased 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine is associated with neural progenitor phenotype in normal brain and shorter survival in malignant glioma. PLoS ONE 7:e41036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pansuriya TC, van Eijk R, d'Adamo P, van Ruler MA, Kuijjer ML, Oosting J et al (2011) Somatic mosaic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are associated with enchondroma and spindle cell hemangioma in Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome. Nat Genet 43:1256–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Park I, Bok R, Ozawa T, Phillips JJ, James CD, Vigneron DB et al (2011) Detection of early response to temozolomide treatment in brain tumors using hyperpolarized 13C MR metabolic imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 33:1284–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P et al (2008) An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science 321:1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pope WB, Prins RM, Albert Thomas M, Nagarajan R, Yen KE, Bittinger MA et al (2012) Non‐invasive detection of 2‐hydroxyglutarate and other metabolites in IDH1 mutant glioma patients using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurooncol 107:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Popovici‐Muller J, Saunders JO, Salituro FG, Travins JM, Yan SQ, Zhao F et al (2012) Discovery of the first potent inhibitors of mutant IDH1 that lower tumor 2‐HG in vivo. ACS Med Chem Lett 3:850–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rohle D, Popovici‐Muller J, Palaskas N, Turcan S, Grommes C, Campos C et al (2013) An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science 340:626–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sabha N, Knobbe CB, Maganti M, Al Omar S, Bernstein M, Cairns R et al (2014) Analysis of IDH mutation, 1p/19q deletion, and PTEN loss delineates prognosis in clinical low‐grade diffuse gliomas. Neuro‐Oncol 16:914–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Saha SK, Parachoniak CA, Ghanta KS, Fitamant J, Ross KN, Najem MS et al (2014) Mutant IDH inhibits HNF‐4alpha to block hepatocyte differentiation and promote biliary cancer. Nature 513:110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sasaki M, Knobbe CB, Itsumi M, Elia AJ, Harris IS, Chio II et al (2012) D‐2‐hydroxyglutarate produced by mutant IDH1 perturbs collagen maturation and basement membrane function. Genes Dev 26:2038–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Semenza GL (2013) HIF‐1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. J Clin Invest 123:3664–3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sener RN (2003) L‐2 hydroxyglutaric aciduria: proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 27:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shim EH, Livi CB, Rakheja D, Tan J, Benson D, Parekh V et al (2014) L‐2‐Hydroxyglutarate: an epigenetic modifier and putative oncometabolite in renal cancer. Cancer Discov 4:1290–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Snuderl M, Triscott J, Northcott PA, Shih HA, Kong E, Robinson H et al (2015) Deep sequencing identifies IDH1 R132S mutation in adult medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol 33:e27–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Soares DP, Law M (2009) Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain: review of metabolites and clinical applications. Clin Radiol 64:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Steenweg ME, Jakobs C, Errami A, van Dooren SJ, Adeva Bartolome MT, Aerssens P et al (2010) An overview of L‐2‐hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase gene (L2HGDH) variants: a genotype‐phenotype study. Hum Mutat 31:380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Struys EA (2013) 2‐Hydroxyglutarate is not a metabolite; d‐2‐hydroxyglutarate and l‐2‐hydroxyglutarate are! Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Struys EA, Salomons GS, Achouri Y, Van Schaftingen E, Grosso S, Craigen WJ et al (2005) Mutations in the D‐2‐hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase gene cause D‐2‐hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Am J Hum Genet 76:358–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Struys EA, Verhoeven NM, Ten Brink HJ, Wickenhagen WV, Gibson KM, Jakobs C (2005) Kinetic characterization of human hydroxyacid‐oxoacid transhydrogenase: relevance to D‐2‐hydroxyglutaric and gamma‐hydroxybutyric acidurias. J Inherit Metab Dis 28:921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sun HR, Yin LH, Li SW, Han S, Song GR, Liu N, Yan CX (2013) Prognostic significance of IDH mutation in adult low‐grade gliomas: a meta‐analysis. J Neurooncol 113:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y et al (2009) Conversion of 5‐methylcytosine to 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 324:930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tonjes M, Barbus S, Park YJ, Wang W, Schlotter M, Lindroth AM et al (2013) BCAT1 promotes cell proliferation through amino acid catabolism in gliomas carrying wild‐type IDH1. Nat Med 19:901–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, Walsh LA, Fang F, Yilmaz E et al (2012) IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature 483:479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. van der Knaap MS, Jakobs C, Hoffmann GF, Nyhan WL, Renier WO, Smeitink JA et al (1999) D‐2‐Hydroxyglutaric aciduria: biochemical marker or clinical disease entity? Ann Neurol 45:111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Venneti S, Felicella MM, Coyne T, Phillips JJ, Gorovets D, Huse JT et al (2013) Histone 3 lysine 9 trimethylation is differentially associated with isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in oligodendrogliomas and high‐grade astrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 72:298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Venneti S, Dunphy MP, Zhang H, Pitter KL, Zanzonico P, Campos C et al (2015) Glutamine‐based PET imaging facilitates enhanced metabolic evaluation of gliomas in vivo. Sci Transl Med 7:274ra17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard‐Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E et al (2013) Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science 340:622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ward PS, Patel J, Wise DR, Abdel‐Wahab O, Bennett BD, Coller HA et al (2010) The common feature of leukemia‐associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha‐ketoglutarate to 2‐hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell 17:225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ward PS, Cross JR, Lu C, Weigert O, Abel‐Wahab O, Levine RL et al (2012) Identification of additional IDH mutations associated with oncometabolite R(‐)‐2‐hydroxyglutarate production. Oncogene 31:2491–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ward PS, Thompson CB (2012) Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell 21:297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Watanabe T, Nobusawa S, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H (2009) IDH1 mutations are early events in the development of astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. Am J Pathol 174:1149–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wise DR, Ward PS, Shay JE, Cross JR, Gruber JJ, Sachdeva UM et al (2011) Hypoxia promotes isocitrate dehydrogenase‐dependent carboxylation of alpha‐ketoglutarate to citrate to support cell growth and viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:1961–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH et al (2011) Oncometabolite 2‐hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha‐ketoglutarate‐dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell 19:17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W et al (2009) IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med 360:765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yen KE, Bittinger MA, Su SM, Fantin VR (2010) Cancer‐associated IDH mutations: biomarker and therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene 29:6409–6417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Zeng L, Morinibu A, Kobayashi M, Zhu Y, Wang X, Goto Y et al (2014) Aberrant IDH3alpha expression promotes malignant tumor growth by inducing HIF‐1‐mediated metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis. Oncogene 34:4758–4766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Zhao S, Lin Y, Xu W, Jiang W, Zha Z, Wang P et al (2009) Glioma‐derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF‐1alpha. Science 324:261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]