Keywords: nerve regeneration, hyperbaric oxygen, near-infrared spectroscopy, cerebral oxygen saturation, traumatic brain injury, oxygen partial pressure, oxygen metabolism, wound healing, neurological function, blood gas analysis, neural regeneration

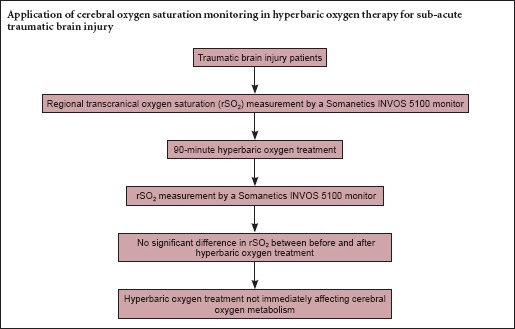

Abstract

Although hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy can promote the recovery of neural function in patients who have suffered traumatic brain injury (TBI), the underlying mechanism is unclear. We hypothesized that hyperbaric oxygen treatment plays a neuroprotective role in TBI by increasing regional transcranial oxygen saturation (rSO2) and oxygen partial pressure (PaO2). To test this idea, we compared two groups: a control group with 20 healthy people and a treatment group with 40 TBI patients. The 40 patients were given 100% oxygen of HBO for 90 minutes. Changes in rSO2 were measured. The controls were also examined for rSO2 and PaO2, but received no treatment. rSO2 levels in the patients did not differ significantly after treatment, but levels before and after treatment were significantly lower than those in the control group. PaO2 levels were significantly decreased after the 30-minute HBO treatment. Our findings suggest that there is a disorder of oxygen metabolism in patients with sub-acute TBI. HBO does not immediately affect cerebral oxygen metabolism, and the underlying mechanism still needs to be studied in depth.

Introduction

Severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability among men between the ages of 20 to 60 years (Werner et al., 2007). TBI can result in cellular energy failure in common metabolic pathways. In the first 24 hours after injury, ischemia results in decreased O2 delivery, leading to inefficient oxidative cerebral metabolism. A cascade of biochemical events lead in turn to mitochondrial dysfunction and a prolonged period of hypometabolism. Furthermore, diffusion barriers to the cellular delivery of O2 develop and persist. The degree to which cerebral oxidative metabolism is restored correlates with the clinical outcome (Sarah et al., 2010). Because advancing the rehabilitation of nervous function can minimize the insults, decrease the neurological disability, and optimize the patients’ prognosis after TBI, it has become an important topic of study.

Despite several encouraging animal studies, human TBI trials assessing different pharmacological neuroprotective agents have all failed to show any efficacy (Tisdall et al., 2007). Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) might be a promising intervention for TBI. HBO could elevate the oxygen concentration gradient and could facilitate regeneration of blood vessels within the injured tissue (Rockswold et al., 1992; Gill et al., 2004). Indeed, this is a major intervention for TBI patients in China during their rehabilitation.

HBO leads to a post-treatment effect (Hadanny et al., 2015), in which HBO retention can occur in injured brain tissue after the HBO cure because of poor blood circulation (Bennett et al., 2014). We hypothesized that because brain-tissue oxygen pressure is higher in the injured area, the cerebral regional transcranial oxygen saturation (rSO2) would also be elevated. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a developing technology for noninvasive assessment of cerebral oxygenation (Hyttel-Sorensen et al., 2015). In recent years, NIRS has been accepted as a means for clinicians to measure the rSO2 of cerebral and somatic tissues in the clinical setting (Drayna et al., 2011). The aim of the current study was to evaluate the differences in bi-hemispheric measurement of cerebral oxygenation using NIRS pre- and post-HBO.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This prospective, observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, China. Informed consent was received from all patients involved in the study, or their relatives, including consent to publish.

Two groups were compared in this study. The control group comprised 20 healthy individuals (hospital staff) and the TBI group comprised 40 TBI patients who were selected from the Department of Neurosurgery, High-tech District Branch of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. According to the usual rehabilitation plan, patients who suffered from a sub-acute traumatic brain injury with a possibility to be treated with HBO were enrolled in the study.

TBI group inclusion criteria

(1) Age 18–60 years, (2) time after TBI: 4–12 days, (3) no contraindication for HBO, and (4) no hypertension or diabetes mellitus.

TBI group exclusion criteria

(1) History of TBI, (2) history of stroke, (3) broken skin on the forehead, or (4) history of severe pulmonary disease (including asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

Healthy group inclusion criteria

(1) Age: 18–60 years, and (2) no history of stroke.

Healthy group exclusion criterion

Broken skin on the forehead.

Treatment

HBO treatment was given to all TBI patients 4–12 days (average 8 days) after injury. The patients sat in a hyperbaric multiplace chamber (Shc2800-8000-10/4, Shanghai 701 Yang Garden Hyperbaric Oxygen Chamber Co., Ltd.) that was compressed to a pressure of 240 kPa within 15 minutes, and then given 100% oxygen with an oronasal mask at a pressure of 240 kPa for three cycles of 30 minutes. In between cycles, they breathed air at a pressure of 240 kPa for 5 minutes. Afterward, they were decompressed to a normal atmospheric pressure over a 15-minute period.

Cerebral oxygen saturation monitor

Cerebral dosimeter sensors were placed on both sides of the forehead with the medial edge of the sensor at the midline. rSO2 was measured for 30 minutes with a Somanetics INVOS 5100 monitor (NIRS monitor, Somanetics INVOS system, Somanetics Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) before the 90-minute HBO treatment. At the same time, arterial blood was sampled for a blood-gas analysis. Fifteen minutes after the HBO treatment, the same measurements were taken for 30 minutes, and the blood sampling was duplicated. In the healthy individuals, rSO2 was measured once over a 30-minute period.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Comparisons within group and between groups were made based on paired t-tests and two sample t-test, respectively. The threshold for statistical significance was set to P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

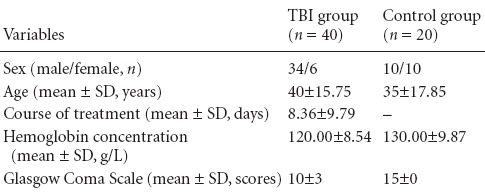

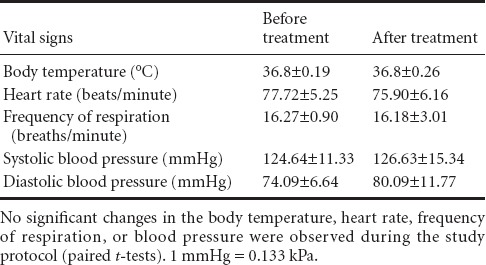

Forty patients with sub-acute TBI were evaluated during the course of this study. There was no difference in age between the two groups (Table 1). Furthermore, no significant changes were observed in body temperature, heart rate, frequency of respiration, or blood pressure during the study protocol (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline data

Table 2.

Vital signs of the traumatic brain injury patients

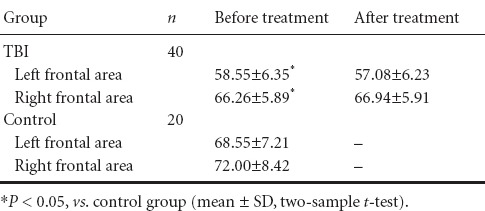

The rSO2

rSO2 was significantly less in the patient group compared with controls (P < 0.05), but did not significantly differ among patients before and after HBO treatment (t = 0.352, P > 0.05). Compared with the left frontal area, rSO2 was not significantly higher in the right (t = 0.469, P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of rSO2 betwen the two groups

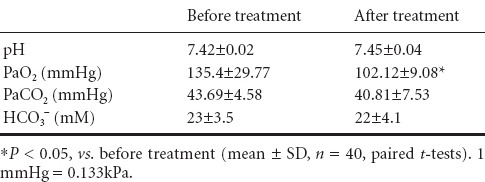

Variables of blood gas analysis

There were no significant differences in the PaCO2, pH, or HCO3 values between pre- and post-HBO treatment. However, we did observe a significant reduction in PaO2 after treatment (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of variables of blood gas analysis in traumatic brain injury

Discussion

This was a report on an observational clinical trial that used NIRS to examine the effect of HBO therapy in TBI patients. rSO2 did not significantly differ among TBI patients before and after HBO treatment. Ischemia and hypoxia are known to be dangerous secondary injuries that can appear 7–14 days after TBI (Vigue et al., 1999). Oxygen delivery to brain tissue could be impaired by the reduced O2 diffusion into brain cells (Menon et al., 2004), which can result in low PO2 levels. PO2 levels in brain tissue is known to be associated with the clinical outcome (van den Brink et al., 2000; Stiefel et al., 2006). Oxygen delivery depends on a pressure gradient from the alveolar spaces to the blood, and finally to the brain tissue itself. Hyperbaric O2 could increase the vital O2 delivery pressure gradient (Beynon et al., 2012), which could subsequently improve cerebral aerobic metabolism after brain injury (Guedes et al., 2016). Studies have shown that HBO decreases the mortality rates and improves the functional outcome in TBI patients (Boussi-Gross et al., 2013). HBO also improves wound healing by amplifying the oxygen gradients along the periphery of the ischemic compounds and by promoting oxygen-dependent collagen formation needed for angiogenesis. Because oxygen exists in the solution, it can reach into the physically obstructed areas where red blood cells cannot pass, which could enable tissue oxygenation despite impaired hemoglobin oxygen transport, such as in the case of carbon monoxide poisoning or severe anemia. PO2 monitoring in brain tissue ranges 200–300 mmHg with HBO at 1.5 ATA.

The principle of NIRS has been well documented (Neshat Vahid et al., 2014). The near-infrared light is absorbed at a wave length of 700–1,300 nm, and passes through a material, which is determined by the molecular properties of the material in the light path (Suffoletto et al., 2012). In the mammalian brain, only hemoglobin and cytochrome c oxidase absorb the near-infrared light, and the extent of this absorption changes with the oxygenation state of these two compounds (Xiao et al., 2004). The rSO2 is accordingly a measure of the blood oxygen saturation in the brain's gas-exchanging circulation (arterioles, capillaries, and veins). Bi-hemispheric measurement of cerebral oxygen saturation could detect oxygenation metabolism in different brain regions. The comparison of rSO2 between the left and right frontal areas has not been previously reported in patients after HBO treatment. NIRS allows a noninvasive assessment of cerebral hemodynamics and oxygenation. The absolute value of the rSO2 measurement, which represents all the cerebral blood compartments except the larger vessels, was a relatively focal measurement. Cerebral oxygenation monitoring using NIRS detected the changes in oxygenation earlier than what standard pulse oximetry can provide (Tobias, 2008). Therefore, NIRS could be a promising and sensitive means to assess cerebral oxygen consumption.

Oxidative metabolism could be markedly reduced in large regions of the brain after TBI (Diringer et al., 2002; Coles et al., 2004; Vespa et al., 2005). Here, we report that the rSO2 of patients with a sub-acute TBI was lower than that of healthy individuals. We also found that the rSO2 of these patients did not significantly change after the HBO treatment. This lack of the cerebral oxygenation elevation after the HBO treatment was not expected. There could be several reasons to explain this phenomenon. The rSO2 values could have been affected by the hemoglobin concentration, skull thickness, the differential path length factor, extracranial blood contamination, the area of the cerebrospinal fluid layer, or the sensor location (Kishi et al., 2003; Yoshitani et al., 2007; Leal-Noval et al., 2010). Furthermore, the NIRS could have analyzed the arterial, venous, or capillary blood, as well as their derived measurements representing the oxygen saturation in these three types of structures (Smith et al., 2009). Most of the cerebral blood volume is venous (Watzman et al., 2000), so the rSO2 might predominantly represent the saturation of hemoglobin in the venous blood bed. When the blood stream is blocked, the rSO2 could correspondingly descend. Additionally, rSO2 could represent a continuous measure of the balance between the delivery and utilization of cerebral oxygen (Buchner et al., 2000; Kolyva et al., 2013), such that the oxygen consumption increases after HBO treatment without raising the rSO2.

As for the decrease in PaO2 in the patients, a potential explanation is that HBO decreases lung function. There could be several mechanisms that might explain this phenomenon. The most reasonable and direct pathophysiologic explanation for our findings could be that extrapulmonary and neurogenic events were involved in the pathogenesis of acute pulmonary function, such as nitric oxide (NO) derived from neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) is involved in a neurogenic mechanism of HBO-induced lung injury that is linked to central nervous system oxygen toxicity through adrenergic/cholinergic pathways (Demchenko et al., 2007; Demchenko et al., 2008). HBO and TBI have been shown to increase the NO synthesis (Shaw et al., 2009). Therefore, NO could be a key to this phenomenon. A second explanation is that pulmonary function was reduced (Thorsen et al., 1998) in cases in which pulmonary O2 toxicity occurred with HBO treatment. However, no studies have provided evidence of any cerebral or pulmonary O2 toxicity with HBO treatment (Rockswold et al., 2010).

There were some limitations in this study. For safety and ethical reasons, we did not observe rSO2 dynamic changes in the hyperbaric chamber. Additionally, the sample size was small.

In conclusion, oxygen metabolism was abnormal in patients with a sub-acute TBI. HBO treatment did not immediately affect their cerebral oxygen metabolism. PaO2 was decreased with treatment, so it should be taken into consideration in TBI patients treated with HBO.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from Suzhou Key Medicine Project Fund of China, No. Szxk201504.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Plagiarism check: This paper was screened twice using Cross-Check to verify originality before publication.

Peer review: This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Copyedited by Phillips A, Robens J, Zhou BC, Wang J, Li JY, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Bennett MH, Weibel S, Wasiak J, Schnabel A, French C, Kranke P. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:Cd004954. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004954.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beynon C, Kiening KL, Orakcioglu B, Unterberg AW, Sakowitz OW. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring and hyperoxic treatment in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2109–2123. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussi-Gross R, Golan H, Fishlev G, Bechor Y, Volkov O, Bergan J, Friedman M, Hoofien D, Shlamkovitch N, Ben-Jacob E, Efrati S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy can improve post concussion syndrome years after mild traumatic brain injury-randomized prospective trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner K, Meixensberger J, Dings J, Roosen K. Near-infrared spectroscopy-not useful to monitor cerebral oxygenation after severe brain injury. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2000;61:69–73. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles JP, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Rice K, Clark JC, Pickard JD, Menon DK. Defining ischemic burden after traumatic brain injury using 15O PET imaging of cerebral physiology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:191–201. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000100045.07481.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demchenko IT, Atochin DN, Gutsaeva DR, Godfrey RR, Huang PL, Piantadosi CA, Allen BW. Contributions of nitric oxide synthase isoforms to pulmonary oxygen toxicity, local vs. mediated effects. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L984–990. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00420.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demchenko IT, Welty-Wolf KE, Allen BW, Piantadosi CA. Similar but not the same: normobaric and hyperbaric pulmonary oxygen toxicity, the role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L229–238. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00450.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diringer MN, Videen TO, Yundt K, Zazulia AR, Aiyagari V, Dacey RG, Jr, Grubb RL, Powers WJ. Regional cerebrovascular and metabolic effects of hyperventilation after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:103–108. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayna PC, Abramo TJ, Estrada C. Near-infrared spectroscopy in the critical setting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:432–439. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182188442. quiz 440-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill AL, Bell CN. Hyperbaric oxygen: its uses, mechanisms of action and outcomes. QJM. 2004;97:385–395. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes VA, Song S, Provenzano M, Borlongan CV. Understanding the pathology and treatment of traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder: a therapeutic role for hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Exp Rev Neurother. 2016;16:61–70. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2016.1126180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadanny A, Efrati S. Oxygen-a limiting factor for brain recovery. Crit Care. 2015;19:307. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1034-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyttel-Sorensen S, Pellicer A, Alderliesten T, Austin T, van Bel F, Benders M, Claris O, Dempsey E, Franz AR, Fumagalli M, Gluud C, Grevstad B, Hagmann C, Lemmers P, van Oeveren W, Pichler G, Plomgaard AM, Riera J, Sanchez L, Winkel P, Wolf M, Greisen G. Cerebral near infrared spectroscopy oximetry in extremely preterm infants: phase II randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2015;350:g 7635. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi K, Kawaguchi M, Yoshitani K, Nagahata T, Furuya H. Influence of patient variables and sensor location on regional cerebral oxygen saturation measured by INVOS 4100 near-infrared spectrophotometers. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2003;15:302–306. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolyva C, Ghosh A, Tachtsidis I, Highton D, Smith M, Elwell CE. Dependence on NIRS source-detector spacing of cytochrome c oxidase response to hypoxia and hypercapnia in the adult brain. Adv Exp Med Boil. 2013;789:353–359. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7411-1_47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Noval SR, Cayuela A, Arellano-Orden V, Marin-Caballos A, Padilla V, Ferrandiz-Millon C, Corcia Y, Garcia-Alfaro C, Amaya-Villar R, Murillo-Cabezas F. Invasive and noninvasive assessment of cerebral oxygenation in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1309–1317. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1920-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon DK, Coles JP, Gupta AK, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Chatfield DA, Aigbirhio F, Skepper JN, Minhas PS, Hutchinson PJ, Carpenter TA, Clark JC, Pickard JD. Diffusion limited oxygen delivery following head injury. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1384–1390. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127777.16609.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neshat Vahid S, Panisello JM. The state of affairs of neurologic monitoring by near-infrared spectroscopy in pediatric cardiac critical care. Cur Opin Pediatr. 2014;26:299–303. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockswold GL, Ford SE, Anderson DC, Bergman TA, Sherman RE. Results of a prospective randomized trial for treatment of severely brain-injured patients with hyperbaric oxygen. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:929–934. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.6.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockswold SB, Rockswold GL, Zaun DA, Zhang X, Cerra CE, Bergman TA, Liu J. A prospective, randomized clinical trial to compare the effect of hyperbaric to normobaric hyperoxia on cerebral metabolism, intracranial pressure, and oxygen toxicity in severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:1080–1094. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.JNS09363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw FL, Winyard PG, Smerdon GR, Bryson PJ, Moody AJ, Eggleton P. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment induces platelet aggregation and protein release, without altering expression of activation molecules. Clin Biochem. 2009;42:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Elwell C. Near-infrared spectroscopy: shedding light on the injured brain. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1055–1057. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819a0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiefel MF, Udoetuk JD, Spiotta AM, Gracias VH, Goldberg A, Maloney-Wilensky E, Bloom S, Le Roux PD. Conventional neurocritical care and cerebral oxygenation after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:568–575. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Rittenberger JC, Guyette F, Hostler D, Callaway C. Near-infrared spectroscopy in post-cardiac arrest patients undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2012;83:986–990. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen E, Aanderud L, Aasen TB. Effects of a standard hyperbaric oxygen treatment protocol on pulmonary function. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:1442–1445. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12061442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias JD. Cerebral oximetry monitoring with near infrared spectroscopy detects alterations in oxygenation before pulse oximetry. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23:384–388. doi: 10.1177/0885066608324380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink WA, van Santbrink H, Steyerberg EW, Avezaat CJ, Suazo JA, Hogesteeger C, Jansen WJ, Kloos LM, Vermeulen J, Maas AI. Brain oxygen tension in severe head injury. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:868–876. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200004000-00018. discussion 876-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P, Bergsneider M, Hattori N, Wu HM, Huang SC, Martin NA, Glenn TC, McArthur DL, Hovda DA. Metabolic crisis without brain ischemia is common after traumatic brain injury: a combined microdialysis and positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:763–774. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigue B, Ract C, Benayed M, Zlotine N, Leblanc PE, Samii K, Bissonnette B. Early SjvO2 monitoring in patients with severe brain trauma. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s001340050878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watzman HM, Kurth CD, Montenegro LM, Rome J, Steven JM, Nicolson SC. Arterial and venous contributions to near-infrared cerebral oximetry. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:947–953. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:4–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, Rodriguez J, Arnold TC, Zhang S, Ferrara D, Ewing J, Alexander JS, Carden DL, Conrad SA. Near-infrared spectroscopy: a tool to monitor cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic changes after cardiac arrest in rats. Resuscitation. 2004;63:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitani K, Kawaguchi M, Miura N, Okuno T, Kanoda T, Ohnishi Y, Kuro M. Effects of hemoglobin concentration, skull thickness, and the area of the cerebrospinal fluid layer on near-infrared spectroscopy measurements. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:458–462. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]