Abstract

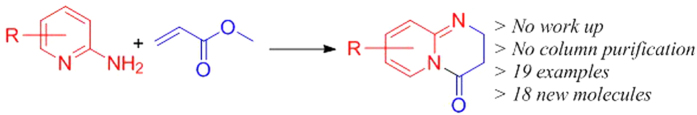

An efficient synthesis of novel 2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones has been reported. Inexpensive and readily available substrates, environmentally benign reaction condition, and product formation up to quantitative yield are the key features of this methodology. Products are formed by the aza-Michael addition followed by intramolecular acyl substitution in a domino process. The polar nature and strong hydrogen bond donor capability of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-ol is pivotal in this cascade protocol.

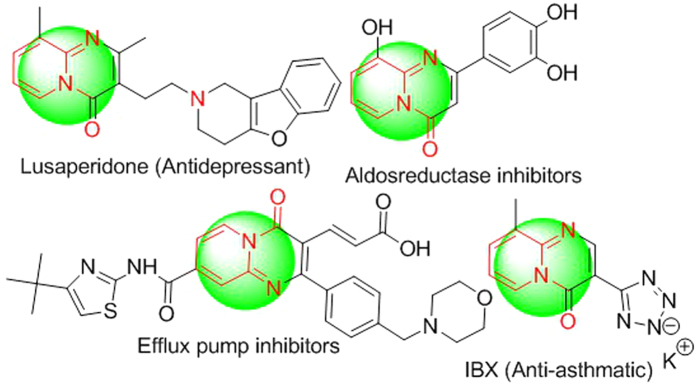

The 1,3-nitrogenous bicyclic frameworks have been illustrious in drug discovery. Many pyrido-pyrimidinone scaffolds (i.e., Fig. 1) have occupied privileged position in medicinal chemistry due to their unprecedented biological activities. It is a key constituent of numerous natural products possessing wide range of therapeutic properties including antitumor, anti-influenza, oxidative burst inhibition, lipid droplet synthesis inhibition, and anti-obesity properties1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Recent studies have revealed that the molecules bearing pyrido-pyrimidinones are in different phases of drug development to treat cancer, hypertension, neurological disorders, etc11,12,13,14,15,16. Some of them have been recognized as aldose reductase inhibitors, efflux pump inhibitors, and hepatitis C virus NS3 protease inhibitors. 1,3-Nitrogenous bicyclics also include marketed drugs for depression and asthma treatment (Fig. 2)2,6,9,14,15.

Figure 1. Synthesis of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones.

Figure 2. Pyrido-pyrimidones bearing marketed drug and drug targets.

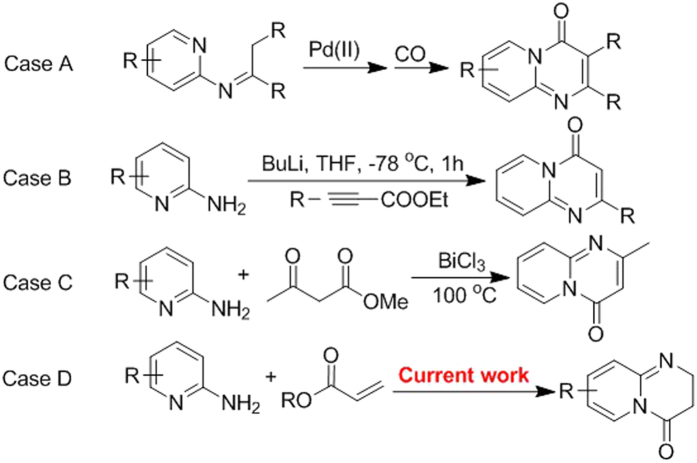

Synthesis of structural variant of pyrido-pyrimidinones is challenging. Zeng et al. have utilized palladium catalyzed C-H activation entailed carbonylative cycloamidation of ketoimines (Fig. 3, Case A)17. It requires a bimetallic combination of palladium and copper along with toxic carbon monoxide in a sophisticated reaction setup. Spring and coworkers have used 2-aminopyrimidine and alkynoates in bicyclic pyrimidones synthesis. The use of butyl lithium is critical and require continuous monitoring of anhydrous condition (Fig. 3, Case B)18. Bicyclic pyrimidones have also been synthesized by using β-oxo esters and 2-amnionpyrimidines in the presence of BiCl3 catalyst (Fig. 3, Case C)11. The use of alkyne Michael addition helps in shifting the position of carbonyl group in pyrimidones19. Dai et al. have reported the Michael addition of anilines with acrylates by using polymer-supported AlCl3 in which they reported one cyclized molecule; 2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (1) among other aza-Michael adducts20. From literature survey it was apparent that there are no reports on the dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones chemistry and their biological activity. It motivated us to design and developed a protocol for their synthesis and investigate their biological activities (Fig. 3, Case D). In this article, we present our results involving sustainable design and catalyst free synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one derivatives.

Figure 3. Strategies for the synthesis of pyrido-pyrimidinone and their derivatives.

Results and Discussion

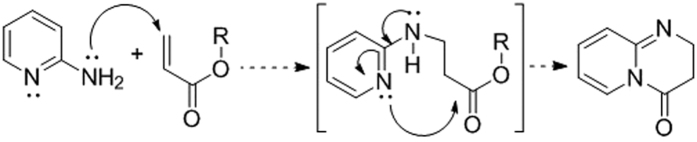

Engage in small molecule research, we wanted to explore the synthesis of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones and their biological activities. Dearth of literature and our interest in its medicinal chemistry encouraged us to design and synthesize bicyclic dihydropyrido-pyrimidinone derivatives. We speculated that the introduction of amine group at second position in pyridine will increase the nucleophilicity of ring-nitrogen and activity of amino group towards nucleophilic aza-Michael addition to electron deficient double bonds. Accordingly, a reaction pathway was envisaged where the amine group undergoes aza-Michael addition and ring nitrogen participates in the exo-trig cyclization for the formation of bicyclic pyrimidinones architecture (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Proposed reaction pathway towards pyrimidones.

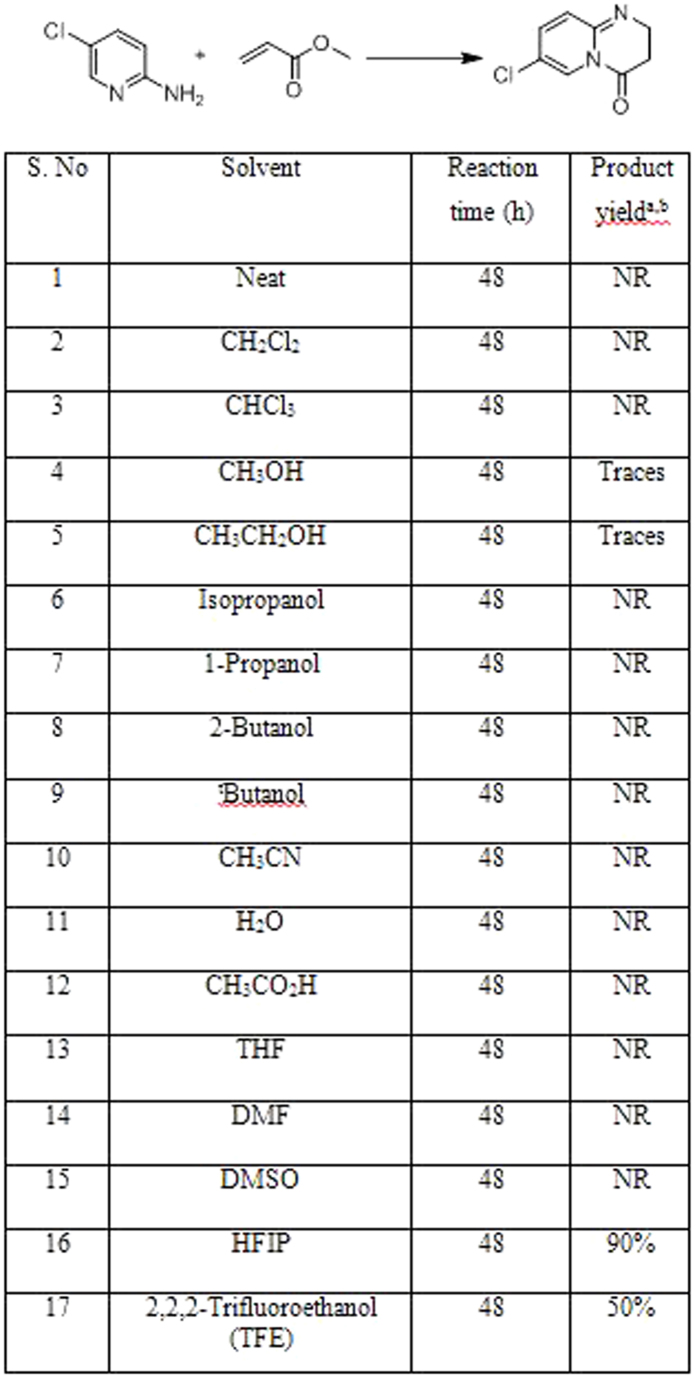

The first step in the synthesis of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones is the aza-Michael addition of 2-aminopyridines with α,β-unsaturated ester. The addition of aromatic amine over electron deficient double bond is well known. In most of the cases, it requires acid catalyst to facilitate nucleophilic aza-Michael type addition. We believed that the use of aromatic nitrogen ring in conjugation with amine functional group increase the probability of catalysis free aza-Michael type addition; which on intramolecular cyclization may yield the desire product. Our aim was to find the reaction condition and appropriate solvent for the facile conversion of aminopyridine to desired dihydropyrimido derivatives. We began our study with the reaction of 2-amino-5-chloropyridine and methyl acrylate in different solvents towards the aza-Michael addition and cyclization protocol. In the beginning the reaction outcome was disappointing as it did not yield the desire product in most of the solvents (Fig. 5, entry 1–15). The increase in reaction temperature did not alter the reaction outcome. The twilight of success started emerging with the reaction in methanol and ethanol (Fig. 5, entries 5 and 6) as it gave the desired product in detectable amount. We attributed the formation of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones to high polarity and inter molecular hydrogen bonding with polar hydroxyl group of methanol and ethanol. Hitherto, we explored the reaction in fluorinated alcohols (Fig. 5, entries 16 and 17). The reaction in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) persuaded the aza-Michael addition cyclization with the quantitative yield of desired product (Fig. 5, entry 16). The most promising part of the reaction was the purity of the isolated product after evaporation or filtration.

Figure 5. Solvent screening and reaction optimization.

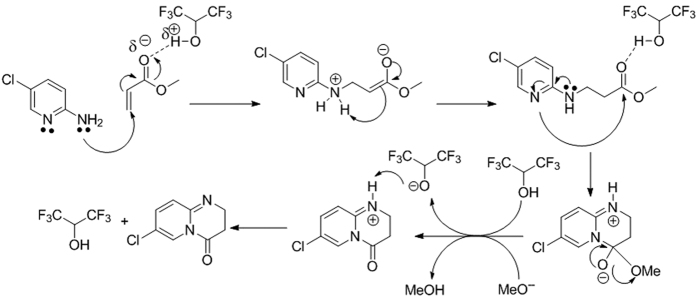

The aza-Michael addition is greatly facilitated by the strong inter molecular hydrogen bonding between hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) and carbonyl group of the Michael acceptor. After the first step, the nucleophilicity of ring nitrogen increases exponentially due to the direct conjugation with amino group; facilitating the exo-trig cyclization to form thermodynamically stable dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Tentative mechanism for the dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones formation.

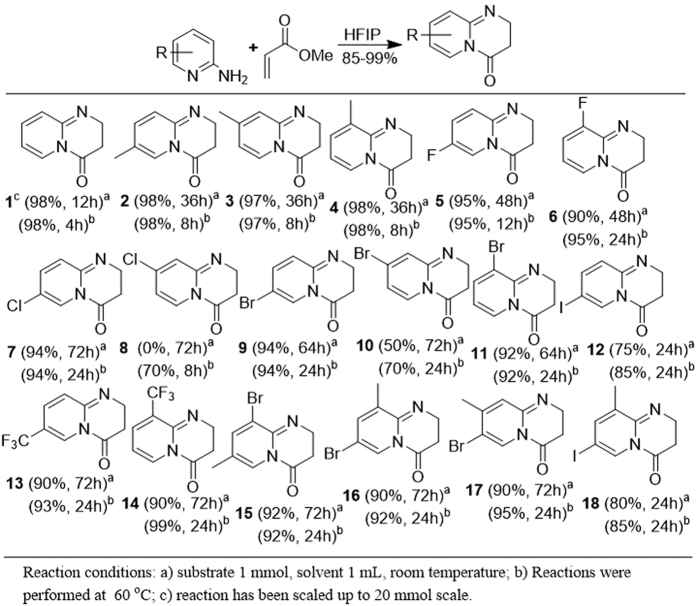

The reaction outcome impelled us to use HFIP as a reaction medium. Subsequently, reactions were performed in HFIP at room temperature without the use of external catalyst. A wide range of substituted 2-aminopyridines were treated with an α,β-unsaturated ester. The reaction of 2-aminopyridine with methyl acrylate (Michael acceptor) completed in 12 hours to give the product (1) in quantitative yield. The presence of electron donating or electron withdrawing substituent had an unfavorable response on the rate of reaction. It may be due to an imbalance on the optimum electron density in the aromatic system (Fig. 7, Substrate 2–16). The methyl substituted 2-aminopyridines formed dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones without differentiating the position of methyl substituent in the ring system. As the use of 2-amino-3-methylpyridine, 2-amino-4-methylpyridine, and 2-amino-5-methylpyridine in catalyst free cascade aza-Michael addition cyclization protocol does not alter reaction rate and product outcome. All methyl substituted substrates gave the desired dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones (2, 3, and 4) in very high yield after 36 hours of stirring at room temperature. The halogen substituted 2-aminopyridines were also utilized in the synthesis of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones. Fluoro substituted 2-aminopyridine gave the desired products (5 and 6) in excellent yield and required 48 hours for the completion of the reaction. Refluxing 2-amino-4-chloropyridine in HFIP for ~8 h formed the product (8) in 70% yield further refluxing of the reaction to completely consume the reactants resulted in the hydrolysis of the pyrido-pyrimidinone to acid derivative. Reactions of bromo substituted aminopyridines were found to be proceeding faster, as these reactions were completed in 48 hours at ambient conditions to give the desired products (9, 10, and 11). The iodo derived substrate also gave the cyclized product (12) in 85% yields. The trifluoromethyl substituted 2-aminopyridines too gave the dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones (13 and 14) in excellent yield. The disubstituted 2-aminopyridines were also investigated in the cascade aza-Michael cyclization strategy. Interestingly, all the substrates gave the desired products (15, 16, 17, and 18) in excellent yields (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Synthesis of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinones using aza-Michael-cyclization strategy.

The effect of alkoxy group in the cyclization step was examined by treating 2-aminopyridine with methyl acrylate, ethyl acrylate, and tert-butyl acrylate. The reaction outcome confirmed that these groups does not involve in the rate determining step and have a trifling effect over the rate of the reaction. Additionally, the scaling up of the reaction to multi-gram scale does not require any special modification and product is isolated in pure form without any difficulty. The reaction solvent was easily recovered, and recycled by simple distillation to achieve the best possible Environmental Factor (E) = 021.

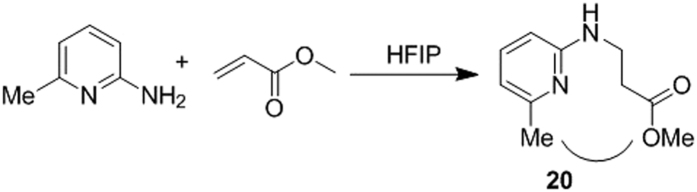

Electron withdrawing groups, specially –NO2, and –COOH, inhibited the formation of desired products. The analysis of reaction mixture confirms the absence of aza-Michael adducts, corroborating that fact that the electron withdrawing groups diminish the nucleophilicity of amino group, which does not allow it to participate in the aza-Michael addition. The incorporation of substituent at 6-position in 2-aminopyridine inhabited the cyclization step as the aza-Michael adduct (19) was isolated as a sole product in the reaction of 2-amino-6-methylpyridines with methyl acrylates (Fig. 8). The ceasing of cyclization is due to the steric hindrance created by methyl substituent at the sixth position (Supporting Information).

Figure 8. Reaction of 2-amino-6-methylpyridine and steric hindrance.

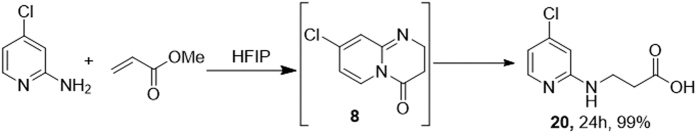

We found abnormal product formation for the reaction of 4-chloro-2-aminopyridine with methyl acrylate under the optimized reaction condition. Analysis of the reaction mixture showed the formation of desired product (8) but refluxing for longer period of time (~24 h) to complete the reaction resulted the further hydrolysis to acid derivative (20). The acid product (20) formed in quantitative yield. Abnormal product formation may be due to the strong electron withdrawing effect of chlorine at 4th position, which facilitate the hydrolysis of pyrimidinone derivative (8) to thermodynamically stable acid derivative (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Formation of acid derivative (20) of 4-chloro-2-aminpyridine.

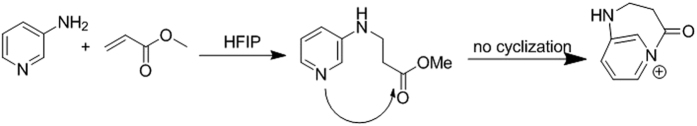

The reaction of 3-aminopyridine with methyl acrylate gave the aza-Michael addition product (Fig. 10). The exclusive formation of Michael adduct with 3-aminopyridine is may be due to increased ring strain and imbalance electronic behavior in seven member ring system.

Figure 10. Reaction with 3-aminopyridine with methyl acrylate.

In this article, we designed and developed a strategy for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one and their derivatives. These molecules are not known in literature except compound (1). The key factor in the discovery is the use of polar and strong hydrogen bonding hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) as a solvent. The use of HFIP facilitates the efficient aza-Michael addition and cyclization in one pot reaction. Detail reaction analysis supported by control experiments gave insight view of the reaction mechanism and its future scope. Ease in synthesis and scalability to multi-gram scale have been the strength of the developed methodology. It gives immense scope to generate a library of new scaffolds required for the drug discovery and biological study. The developed reaction is clean and product could be isolated by simple filtration or evaporation. Additionally, it does not require any purification as the reaction is clean and free from the unwanted by products.

Methods

General procedure for the synthesis of dihydropyrido-pyrimidinone

Mixture of 2-aminopyridine (1 mmol) and methyl acrylate (1.1 mmol) in 1 mL HFIP was stirred or refluxed for a specified time. Progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After the completion of the reaction, solid was filtered to get the product. For a homogenous reaction mixture, solvent was evaporated to get the product.

7-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (2)

White solid powder, m. p. = 121.3 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1635, 1584, 1387. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.39 (dd, J = 2.0, 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.28 (s, 1 H), 6.93 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1), 4.25 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.71 (t, 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.21 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.9, 156.9, 142.4, 135.2, 123.3, 121.8, 50.5, 29.2, 17.2. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H11N2O [M + H]+ 163.1, found 163.1.

8-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (3)

Colorless solid needles, m. p. = 145.8 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1642, 1475. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.27 (d. J = 6.6 Hz, 1 H), 6.53 (s, 1 H), 6.32 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1 H), 4.10 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.48 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.11 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.0, 156.5, 152.0, 136.3, 120.4, 113.8, 49.0, 28.5, 20.6. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H11N2O [M + H]+ 163.1, found 163.1.

9-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (4)

Fluffy white solid, m. p. = 122.7 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1638, 1593, 1531. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 7.30 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.44 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.18 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.57 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.15 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.9, 157.2, 138.3, 135.2, 131.7, 111.4, 50.6, 29.2, 18.3. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H11N2O [M + H]+ 163.1, found 163.1.

7-Fluoro-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (5)

White solid powder, m. p. = 262.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1653, 1558, 1498, 1308. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 8.12 (t, J = 3.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 (dt, J = 2.9, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.67 (dd, J = 5.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.49 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ = 174.4, 156.0, 150.5 (1JC-F = 232.4 Hz), 131.7 (2JC-F = 22.3 Hz), 126.3 (2JC-F = 37.7 Hz), 123.4 (3JC-F = 6.9 Hz), 50.0, 29.1. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H8FN2O [M + H]+ 167.1, found 167.1.

9-Fluoro-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (6)

White amorphous solid, m. p. = 205.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1635, 1620, 1483, 1340. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 7.69 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.56 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.63 (dd, J = 6.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.36 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.52–2.49 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ = 174.2, 149.8 (1JC-F = 226.8 Hz), 135.6, 122.7 (2JC-F = 17.4 Hz), 122.6, 109.3, 49.9, 29.4. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H8FN2O [M + H]+ 167.1, found 167.1.

7-Chloro-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (7)

White amorphous solid, m. p. = 127.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1623, 1485, 1395, 826. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.46 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.42 (s, 1 H), 6.93 (dd, J = 1.1, 8.9 Hz, 1 H), 4.29 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.75 (t, J = 4.2 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 174.6, 156.7, 140.4, 135.0, 124.7, 118.4, 50.7, 28.9. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H7ClN2O [M + H]+ 183.0, found 183.0.

8-chloro-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (8)

White solid powder, m. p. = 142.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1639, 1490, 750. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.69 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (s, 1 H), 7.71 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.77 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.95 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 167.2, 151.0, 150.3, 143.4, 119.6, 115.0, 50.4, 28.8. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H7ClN2O [M + H]+ 183.0, found 183.0.

7-Bromo-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (9)

Brownish solid, m. p. = 167 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1640, 1493, 529. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 7.93 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.54 (dd, J = 2.2, 9.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.71 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.29 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.54 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ = 174.7, 156.5, 142.8, 138.7, 123.8, 103.8, 50.0, 29.0. HRMS (ESI-FTMS Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H7BrN2O [M + H]+ 228.9820, found 228.9795.

8-bromo-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (10)

White solid powder, m. p. = 305.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1636, 1479, 549. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 8.51 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.85 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.52 (s, 1 H), 4.71 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.96 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ = 167.4, 149.3, 142.9, 141.4, 122.8, 118.0, 50.5, 28.7. HRMS (ESI-FTMS Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H7BrN2O [M + H]+ 228.9820, found 228.9795.

9-Bromo-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (11)

White solid powder, m. p. = 235.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1640, 1479, 541. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 8.19 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1 H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 6.58 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.34 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.48 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ = 174.6, 154.6, 143.3, 139.7, 116.0, 111.0, 50.7, 29.4. HRMS (ESI-FTMS Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H8BrN2O [M + H]+ 228.9820, found 228.9800.

7-Iodo-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (12)

Brownish solid, m. p. = 156.0 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.35 (s, 1 H), 7.77 (dd, J = 2.0, 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.56 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.43 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.6, 153.3, 147.4, 144.1, 123.5, 49.5, 29.3. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H7IN2O [M] 274.9681, found 274.9678.

7-(Trifluoromethyl)-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (13)

Colorless solid, m. p. = 126.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1652, 1558, 1336. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ 8.44 (s, 1 H), 7.79 (dd, J = 2.1, 9.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.82 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.37 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.52 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6 + CDCl3): δ = 175.1, 157.9, 139.5, 139.4, 135.3, 122.9, 49.8, 29.1. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H8F3N2O [M + H]+ 217.0, found 217.0.

9-(trifluoromethyl)-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (14)

White amorphous solid, m. p. = 91.0 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1624, 1483, 1366. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 6.74 (t, J = 1.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.38 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.54–2.49 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.1, 154.0, 144.2, 140.1, 140.0, 118.8, 109.2, 50.0, 29.0. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H8F3N2O [M + H]+ 217.0, found 217.0.

9-Bromo-7-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (15)

Brownish solid, m. p. = 115.2 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1664, 1587, 1478, 603. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.01 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.76 (s, 1 H), 4.29 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.44 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.11 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 174.6, 153.5, 145.3, 137.6, 120.6, 115.7, 50.7, 29.5, 16.6. HRMS (ESI-FTMS Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H10BrN2O [M + H]+ 242.9898, found 242.9889.

7-Bromo-9-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (16)

Yellowish amorphous solid, m. p. = 110.8 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1640, 1604, 1583, 1482, 603. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.45 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (s, 1 H), 4.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.31 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 173.6, 157.8, 147.6, 160.5, 159.3, 157.8, 157.2, 50.7, 19.7, 19.0.; HRMS (ESI-FTMS Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H10BrN2O [M + H]+ 242.9898, found 242.9913.

7-Bromo-8-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (17)

White solid, m. p. = 130.5 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1641, 1593, 530. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.71 (s, 1 H), 6.76 (s, 1 H), 4.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.64 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.30 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 169.8, 151.7, 147.7, 133.0, 117.4, 104.1, 45.3, 24.3, 17.9. HRMS (ESI-FTMS Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H10BrN2O [M + H]+ 242.9898, found 242.9899.

7-Iodo-9-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (18)

Brown solid, m. p. = 138.3 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 1640, 1483, 537. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.52 (s, 1 H), 8.22 (s, 1 H), 4.53 (br s, 2 H), 2.72 (br s, 2 H), 2.20 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 170.7, 150.9, 150.3, 149.6, 143.2, 129.2, 50.4, 29.1, 17.1. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C9H9IN2O [M + H]+ 288.9, found 288.9.

Methyl 3-[(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)amino]propanoate (19)

Viscous liquid, 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.34–7.27 (m, 1 H), 6.45 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.69 (s, 1 H), 3.60 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.64 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2 H), 2.38 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 172.8, 157.8, 157.0, 137.7, 112.3, 103.4, 51.7, 37.6, 34.0, 24.3. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C10H15N2O2 [M + H]+ 165.1, found 165.1.

3-[(4-chloropyridin-2-yl)amino]propanoic acid (20)

White solid powder, m. p. = 283.3 °C. IR (thin film, cm−1): 3360, 1710, 1483. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.78 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.68 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (s, 1 H), 4.71 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.8, 171.6, 126.0, 150.3, 112.0, 105.6, 54.7, 33.7. ESI Mass (m/z): calcd for C8H7ClN2O [M + H]+ 183.0, found 184.0.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Alam, M. A. et al. Hexafluoroisopropyl alcohol mediated synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones. Sci. Rep. 6, 36316; doi: 10.1038/srep36316 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the College of Science and Mathematics, Arkansas State University, Jonesboro. This work was also supported by Arkansas Statewide MS facility, Grant Number P30 GM103450 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for recording mass spectra. This publication was made possible by the Arkansas INBRE program, supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (P20 GM103429). Arkansas Biosciences Institute-Arkansas State University (ABI-A-state) start-up fund helped to complete this project. Hessa and Zakeyah are thankful to the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission (SACM) for giving scholarship. We would like to thank Dr. Fabricio Medina-Bolivar (Arkansas State University) for helping the mass spectrometry analysis of some samples. The LTQ-XL mass spectrometer was acquired with funds from National Science Foundation-EPSCoR (grant # EPS-0701890; Center for Plant-Powered Production-P3), Arkansas ASSET Initiative and the Arkansas Science & Technology Authority.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.A.A. envisioned and designed the experiments. M.A.A. also wrote the paper. Z.A., H.A., D.J., E.D., A.G. and T.Y. performed the experiments and collected analytical data under the supervision of M.A.A.

References

- Koyama N. et al. Relative and Absolute Stereochemistry of Quinadoline B, an Inhibitor of Lipid Droplet Synthesis in Macrophages. Org Lett 10, 5273–5276 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansi J. D. et al. Oxidative Burst Inhibitory and Cytotoxic Indoloquinazoline and Furoquinoline Alkaloids from Oricia suaveolens. J. Nat. Prod. 71, 1942–1945 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G. et al. Neosartoryadins A and B, Fumiquinazoline Alkaloids from a Mangrove-Derived Fungus Neosartorya udagawae HDN13-313. Org. Lett. 18, 244–247 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Roos D., Stadtmüller P. & Decker M. A simple heterocyclic fusion reaction and its application for expeditious syntheses of rutaecarpine and its analogs. Tetrahedron Letters 55, 3607–3609 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Schramm A. & Hamburger M. Gram-scale purification of dehydroevodiamine from Evodia rutaecarpa fruits, and a procedure for selective removal of quaternary indoloquinazoline alkaloids from Evodia extracts. Fitoterapia 94, 127–133 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. et al. Scaffold Diversity Inspired by the Natural Product Evodiamine: Discovery of Highly Potent and Multitargeting Antitumor Agents. J. Med. Chem. 58, 6678–6696 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebhun J. F., Roloff S. J., Velliquette R. A. & Missler S. R. Identification of evodiamine as the bioactive compound in evodia (Evodia rutaecarpa Benth.) fruit extract that activates human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). Fitoterapia 101, 57–63 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. et al. Evodiamine Improves Diet-Induced Obesity in a Uncoupling Protein-1-Independent Manner: Involvement of Antiadipogenic Mechanism and Extracellularly Regulated Kinase/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling. Endocrinology 149, 358–366 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W. J. et al. Rutaecarpine prevented dysfunction of endothelial gap junction induced by Ox-LDL via activation of TRPV1. Eur J Pharmacol 756, 8–14 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashiach R. & Meijler M. M. Total Synthesis of Pyoverdin D. Org. Lett. 15, 1702–1705 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roslan I. I., Lim Q.-X., Han A., Chuah G.-K. & Jaenicke S. Solvent-Free Synthesis of 4H-Pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones Catalyzed by BiCl3: A Green Route to a Privileged Backbone. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2351–2355 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky A. R., Rogers J. W., Witek R. M. & Nair S. K. Novel syntheses of pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-2-ones, 2H-quinolizin-2-ones, pyrido[1,2-a]quinolin-3-ones, and thiazolo[3,2-a]pyrimidin-7-ones. Arkivoc 2004, 52–60 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Shakhidoyatov K. M. & Elmuradov B. Z. Tricyclic quinazoline alkaloids: isolation, synthesis, chemical modification, and biological activity. Chem. Nat. Compd. 50, 781–800 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Motta C. L. et al. Pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one Derivatives as a Novel Class of Selective Aldose Reductase Inhibitors Exhibiting Antioxidant Activity. J. Med. Chem. 50, 4917–4927 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K. et al. MexAB-OprM specific efflux pump inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Part 6: Exploration of aromatic substituents Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14, 8506–8518 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietze L. F. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Chem Rev, 1996, 96, 115–136 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Chen T., Fu S., Jiang H. & Zeng W. Pd-catalyzed carbonylative cycloamidation of ketoimines for the synthesis of pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones. Chem. Commun. 51, 9377–9380 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanine T. A. et al. Concise synthesis of rare pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-2-ones and related nitrogen-rich bicyclic scaffolds with a ring-junction nitrogen. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 1031–1038 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. et al. Catalyst-free synthesis of alkyl 4-oxo-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine-2-carboxylate derivatives on water. Tetrahedron 70, 2761–2765 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Dai L., Zhang Y., Dou Q., Wang X. & Chen Y. Chemo/regioselective Aza-Michael additions of amines to conjugate alkenes catalyzed by polystyrene-supported AlCl3. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1712–1716 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Delidovich I. & Palkovits R. Catalytic versus stoichiometric reagents as a key concept for Green Chemistry. Green Chem. 18, 590–593 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.