Abstract

Objective

To assess the repair results of acromioclavicular dislocations (ACJD) grades III and V, with anchors without eyelet, when compared with other techniques, and to evaluate factors that can affect the final result.

Methods

A retrospective study of 36 patients with ACJD grades III and V in the Rockwood classification, 12 treated with anchors without eyelet, 11 with one tightrope, six with two tightropes, and six with subcoracoid cerclage, operated from September 2012 to February 2015. Patients were assessed radiographically and through DASH, UCLA, the visual analog scale of pain (VAS) and the Short-Form 36 (SF-36). Surgical time and the possible influence of some factors in the outcome were also assessed.

Results

The mean DASH score was 6.7; UCLA, 32.9; VAS, 1.2; and SF-36, 79.47. Radiographically, the final mean measurement was 9.93 mm, with no statistical difference between the groups. The mean surgical time for Group I was 31 min; Group II, 19 min; Group III, 29 min; and Group IV, 59 min. There was a significant difference between Groups II and IV when compared with the study group. The initial and immediate post-operative ACJD measurements ACJD were correlated with the final measure.

Conclusion

The repair of acute ACJD with anchors without eyelet is as effective as the other methods, with significantly shorter operative time when compared with the subcoracoid cerclage technique. The final radiological result is influenced by the coracoclavicular initial distance and the immediate postoperative measurement.

Keywords: Acromioclavicular joint, Suture anchors, Treatment outcome

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar os resultados do reparo das luxações acromioclaviculares (LAC) graus III e V, com âncoras sem eyelet, e comparar com outras técnicas, bem como fatores que possam interferir no resultado final.

Métodos

Estudo retrospectivo de 35 pacientes com LAC grau III e V, pela classificação de Rockwood, 12 tratados com âncoras sem eyelet, 11 com um Tightrope, seis com dois Tightropes e seis com amarrilho subcoracoide, operados de setembro de 2012 a fevereiro de 2015. Os pacientes foram avaliados radiograficamente e pelos escores de DASH, UCLA, pela escala visual analógica de dor (EVA) e pelo Short-Form 36 (SF36). O tempo cirúrgico e a possível interferência de alguns fatores no resultado final também foram avaliados.

Resultados

A média dos escores foi de 6,7 no DASH; 32,9 no UCLA; 1,2 na EVA e 79,47 no SF-36. Radiograficamente, a medida final média entre o coracoide e a clavícula foi de 9,93 mm, sem diferença estatística entre os grupos. Quanto ao tempo cirúrgico, a média do grupo I foi de 31 minutos; do grupo II, 19 minutos; do grupo III, 29 minutos e do grupo IV, 59 minutos, houve diferença significativa entre os grupos II e IV, quando comparados com o grupo em estudo. A medida inicial da LAC e a medida pós-operatória imediata (POI) tiveram correlação com a medida final.

Conclusão

O reparo da LAC aguda com âncoras sem eyelet é tão eficaz quanto outros métodos e com tempo cirúrgico significativamente menor quando comparado com a técnica de amarrilho subcoracoide. O resultado radiológico final é influenciado pela distância coracoclavicular inicial e do POI.

Palavras-chave: Articulação acromioclavicular, Âncoras de sutura, Resultado do tratamento

Introduction

The true incidence of acromioclavicular joint dislocations (ACJD) is not known, since many affected individuals do not seek treatment. Approximately 12% of all dislocations involving the shoulder affect the acromioclavicular joint.

Athletes who participate in contact sports (e.g., football, rugby, martial arts) are at higher risk. ACJD is the most common reason why athletes seek medical care following a traumatic event in the shoulder; glenohumeral dislocation is the second most frequent cause.1, 2

Men are more commonly affected, with an approximate ratio of 5:1,3 and younger subjects (<35 years) present this condition more often, mainly due to their greater participation in high-risk activities. Males in the second to fourth decades of life have the highest frequency of ACJD and present, in most cases, partial injuries of the ligaments.3

Depending on the severity of the trauma, an individual may injure one or all of the ligaments, leading to different degrees of ACJD.1 The most commonly used classification is that of Rockwood,4 which stratifies this condition into six types.

The main function of the acromioclavicular joint and its ligaments is to sustain the scapula and connect the upper limb to the axial skeleton. In ACJD, this connection is lost; due to gravity, the arm becomes lower relative to the clavicle, which can lead to greater contact of the acromion on the tendon of the supraspinatus muscle and thus cause symptoms of impact and tendon injury, neurological symptoms due to traction of the brachial plexus, and dyskinesia of the scapula.5, 6

One of the first methods of ACJD treatment was fixation with Kirschner wires after closed reduction. This technique gives good results, but it has not been routinely used due to rare but potentially fatal complications that can occur due to breakage and migration of material.7

There are several surgical techniques for treating acute ACJD; coracoclavicular fixation with subcoracoid ligation is one of the most commonly used. The literature presents studies that compare the biomechanical differences of several techniques, but few compare clinical and radiological differences in the results of the various methods.8

One option for the surgical treatment of ACJD is the coracoclavicular stabilization using suture anchors fixed in the coracoid process, tying the knots in the clavicle through bone tunnels.9, 10

Results with this technique are divergent in the literature due to a possible role of the anchor eyelet (Fig. 1), which precipitates the breakage of the wire, thus causing procedure failure.11

Fig. 1.

Difference between anchors with eyelet (arrow) and without eyelet.

The use anchors without eyelet (Fig. 1), in which the high-strength wire exits directly from the anchor itself, may be a solution to this problem; the anchor is made of a material similar to that of the wire, avoiding the contact of the latter with a more rigid material that could break it.

Material and methods

Medical records of 36 patients who underwent surgical treatment of acute ACJD grades III and V, operated by a single surgeon at a single center between September 2012 and February 2015, were retrospectively reviewed. Age, gender, side, and ACJD classification distribution is shown in Table 1. The study included patients with shoulder trauma who had ACJD grades III or V, and who were operated in up to 30 days from the time of injury. In addition to conventional radiographs (AP, scapula profile, and axillary profile), all radiographs for diagnosis were made in the orthostatic position, with a weight of 2.5 kg on each limb, featuring both acromioclavicular joints in same image (Fig. 2). The minimum follow-up time was set as six months. The exclusion criteria in the selection of patients comprised cases of ACJD grade IV, cases associated with fractures at other sites of the shoulder girdle, and cases that were operated 30 days after injury date.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Patient | Age | Sex | Side | ACJD Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | ||||

| 1 | 40 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 2 | 42 | Female | Left | 5 |

| 3 | 43 | Male | Left | 3 |

| 4 | 48 | Male | Left | 3 |

| 5 | 19 | Male | Left | 3 |

| 6 | 24 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 7 | 21 | Male | Right | 5 |

| 8 | 58 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 9 | 65 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 10 | 20 | Male | Right | 5 |

| 11 | 23 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 12 | 22 | Male | Right | 5 |

| Group II | ||||

| 1 | 34 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 2 | 60 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 3 | 22 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 4 | 32 | Male | Left | 3 |

| 5 | 19 | Male | Right | 3 |

| 6 | 36 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 7 | 28 | Male | Left | 3 |

| 8 | 32 | Male | Right | 5 |

| 9 | 28 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 10 | 22 | Male | Right | 5 |

| 11 | 43 | Male | Right | 3 |

| Group III | ||||

| 1 | 50 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 2 | 29 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 3 | 37 | Male | Right | 3 |

| 4 | 23 | Male | Right | 5 |

| 5 | 35 | Male | Right | 3 |

| 6 | 29 | Male | Right | 3 |

| 7 | 27 | Male | Right | 5 |

| Group IV | ||||

| 1 | 27 | Male | Left | 3 |

| 2 | 20 | Male | Right | 3 |

| 3 | 36 | Male | Left | 5 |

| 4 | 69 | Male | Right | 3 |

| 5 | 50 | Male | Right | 5 |

| 6 | 59 | Female | Left | 5 |

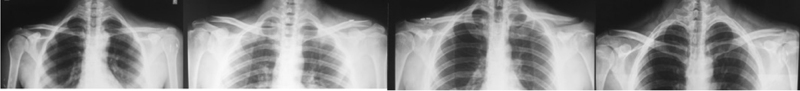

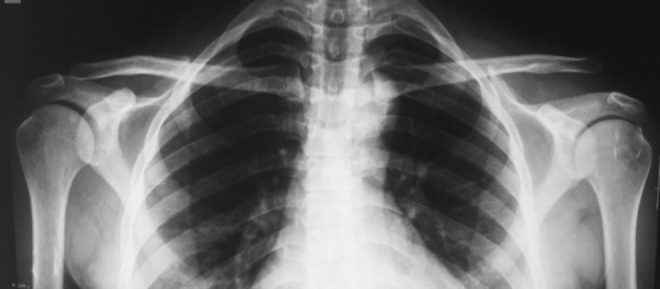

Fig. 2.

Standard stress radiography presenting the acromioclavicular joints in the same image, demonstrating an ACJD V to the left.

Surgical technique

Surgery was performed with patient under general anesthesia and brachial plexus block, in a beach chair position. An incision of approximately 2–3 cm (Fig. 3) was made directly on the distal end of the clavicle, which was osteotomized in its distal 0.5 cm and removed together with the meniscus, as described by some authors in specific cases.12 Anteriorly to the clavicle, the coracoid was digitally identified by palpation, i.e., without direct visualization, the authors would position the anchor insertion guide directly on its superior face. Two double-loaded 2.9-mm anchors (Juggerknot-Biomet) were used in all cases. Four bone tunnels were created in the clavicle using a 2-mm drill, 2 cm from the end of the clavicle; tunnels were square-shaped, with 1 cm between them. Two wires were passed through each of them to repair the dislocation. With these same wires, the deltoid and trapezius were reinserted; these are often affected, mainly in ACJD grade V lesions.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative aspect.

Postoperative period

Patients remained in continuous immobilization with a sling for six weeks, after which rehabilitation was initiated. Physical therapy was initially indicated only for range of motion gain; after this was completed, muscle-strengthening phase was initiated, lasting about three months.

Statistical analysis

The results of the scores of different groups were analyzed in SPSS (IBM) using the Kruskal–Wallis test, which is similar in methodology to the Mann–Whitney, but allows for the assessment of more than two groups simultaneously. Surgical time and radiographic measurements, which were discrete variables with normal distribution, were analyzed by Student's t-test, compared in pairs, using Excel. For all tests, a confidence interval of 95% was calculated and p-values <0.05 were considered to be significant. The possible variables that could affect the final result were assessed in Excel using Pearson's coefficient. Values between 0 and 0.3 were considered to have a weak correlation; between 0.3 and 0.6, moderate correlation; and greater than 0.6, strong correlation. When inverse relationship occurs, values are negative and were considered using the same principle.

Results

The medical records of 36 patients operated in this service by a single surgeon from September 2012 to February 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients were divided into four groups according to the surgical technique used: minimally invasive surgery using anchors without eyelet (Group I); arthroscopy with use of a tightrope (Group II); arthroscopy with use of two tightropes (Group III); and, open repair with subcoracoid ligation using four high-resistance wires (Group IV) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Immediate postoperative image.a

aGroups I, II, III, and IV, from left to right, respectively.

The mean age of the patients was 33.4 years, with no significant difference between the groups (p = 0.696). Mean follow-up was 20.2 months (6–38.03). Regarding the causes of ACJD, 24 (67%) occurred due to sporting accidents, nine (25%) due to car accidents, and three (8%) due to household accidents. As for the side, 15 (42%) occurred on the right and 21 (58%) of the left; the dominant side was affected in 16 (44%) cases. Mean preoperative distance between the coracoid and clavicle was 19.34 mm (10.86–29.38); regarding the classification, 23 cases of ACJD V and 13 ACJD III, there was no significant difference between groups (Table 2). Mean time between the injury and surgery was 7.57 days (1–30).

Table 2.

Measurements of the distance between the coracoid and clavicle, and quantitative analysis of the ACJD classification.

| Mean ACJD measurement, in mm | ACJD III | ACJD V | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 19.1 | 3 | 9 |

| Group II | 19.1 | 4 | 7 |

| Group III | 20.2 | 3 | 4 |

| Group IV | 17.9 | 3 | 3 |

| p-Value between I and II | 0.86 | –a | – |

| p-Value between I and III | 0.97 | – | – |

| p-Value between I and IV | 0.96 | – | – |

As this is a score presenting non-normal distribution, it was not possible to use the t-test to calculate the p-value.

Mean time of surgical procedure was 31 min in Group I, 19 min in Group II, 29 min in Group III, and 59 min in Group IV, with a statistically significant difference for Group I in relationship to Groups II and IV. Patients were clinically and radiologically assessed at one, two, four, and six weeks, three and six months, and one and two years postoperatively. The percentage of loss of reduction, measured by the ratio of the loss in millimeters on the measure achieved in the immediate post-operative period, was significantly different for Group I in relationship to Groups II and IV (Table 3). The moment of loss of reduction was, on average, at the 13th week, with no difference between groups.

Table 3.

Surgical time and pre- and postoperative measurements of the coracoclavicular space with long-term losses of the reduction achieved in the immediate postoperative period.a

| Surgical time in minutes | Pre-op measurement (mm) | Immediate post-op measurement (mm) | Final measurement (mm) | Immediate post-op reduction percentage loss | Period in which the loss of reduction occurred, in weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 31 | 19.1 | 4.89 | 8.23 | 68% | 14.5 |

| Group II | 19 | 19.1 | 5.45 | 11.25 | 106% | 12.7 |

| Group III | 29 | 20 | 4.96 | 8.17 | 65% | 18.8 |

| Group IV | 59 | 18 | 4.27 | 8.86 | 107% | 20.2 |

| p-Value (between I and II) | <0.000000001 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| p-Value (between I and III) | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.47 | 0.4 | 0.42 |

| p-Value (between I and IV) | 0.000002 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.24 | 0.2 | 0.09 |

Values are presented as means. The percentage of loss of reduction was calculated by comparing the outcome of the measurement between the coracoid and clavicle, with the measurement observed in the immediate postoperative period.

In the clinical evaluation at six months, one year, and two years after surgery, the DASH, UCLA, VAS, and SF-36 scores were used. Mean DASH score was 6.7 points; mean UCLA was 32.9, with 17 (48%) excellent results, 18 (50%) good, and one regular (2%); mean VAS was 1.2 points, with 32 (91%) cases of minor pain and three (9%) cases of moderate pain; and mean SF-36 score was 79.47, with no significant difference between groups (Table 4, Table 5).

Table 4.

Results of clinical scores (UCLA, DASH, and VAS).a

| UCLA | DASH | VAS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 32.4 ± 2.5 (26–35) | 7.7 ± 7.1 (0.83–25) | 1.2 ± 1.3 (0–4) |

| Group II | 33.4 ± 2.3 (27–35) | 5.9 ± 9.8 (0–34) | 1.2 ± 2.0 (0–7) |

| Group III | 32.0 ± 2.0 (29–35) | 5.8 ± 9.0 (0.83–25.83) | 1.8 ± 1.2 (0–4) |

| Group IV | 29.4 ± 1.9 (30–35) | 6.5 ± 19.1 (0–47.5) | 0.9 ± 1.2 (0–3) |

| Kruskal–Wallis test (p-value) | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.16 |

Values are expressed as mean and standard deviation; the range is presented in parentheses.

Table 5.

SF-36 score, stratified by its areas.a

| Functional capacity | Limitation due to physical aspects | Pain | General health | Vitality | Social aspects | Limitations due to emotional aspects | Mental health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 93 ± 6.7 (84–100) | 76 ± 32.3 (25–100) | 88 ± 18.5 (62–100) | 74 ± 18.5 (55–100) | 75 ± 15.9 (40–90) | 85 ± 15.3 (45–100) | 75 ± 34.2 (0–100) | 90 ± 8.6 (80–100) |

| Group II | 92 ± 12.5 (60–100) | 75 ± 38.2 (0–100) | 73 ± 28.4 (0–100) | 72 ± 19 (45–100) | 82 ± 15 (50–100) | 92 ± 19 (37.5–100) | 88 ± 21.3 (33.3–100) | 78 ± 24 (33–100) |

| Group III | 95 ± 9 (75–100) | 88 ± 19 (50–100) | 73 ± 21 (41–95) | 70 ± 16 (55–100) | 82 ± 12 (80–100) | 84 ± 12 (75–100) | 88 ± 25 (33.3–100) | 75 ± 18 (52–100) |

| Group IV | 87 ± 24 (40–100) | 75 ± 38 (0–100) | 81 ± 100 | 75 ± 25 (35–100) | 92 ± 8 (80–100) | 90 ± 17 (62.5–100) | 74 ± 39 (0–100) | 89 ± 15 (64–100) |

| Kruskal–Wallis test | 0.9 | 0.91 | 0.23 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.8 | 0.23 |

Values are expressed as mean and standard deviation; the range is presented in parentheses.

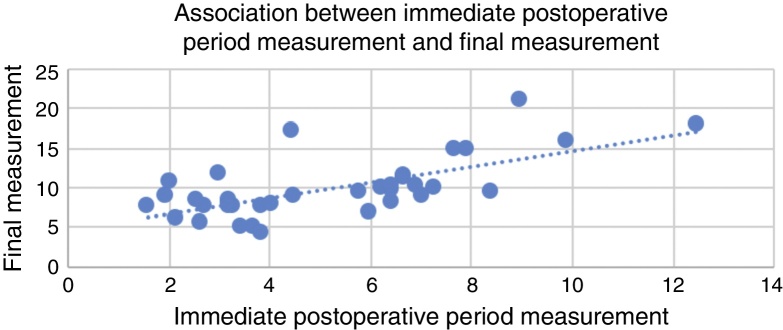

Some factors that could be correlated with the final clinical and radiological outcome were assessed. A strong correlation was observed between the reduction achieved in the immediate postoperative period and at final follow-up, as well as a moderate relationship between the measurement at the time of the injury and final measurement (Table 6). Fig. 5 shows the scatter plot for the measurement of the reduction in the immediate postoperative period and final measurement, showing a strong correlation between these measures.

Table 6.

Correlation of variables with the outcome (Pearson's coefficient).

| Final measurement | VAS | DASH | UCLA | SF36 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate post-op measurement | 0.67 | 0.24 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.5 |

| Initial measurement | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.5 | −0.18 | −0.12 |

| Time to surgery | 0.1 | 0.16 | 0.5 | 0.21 | −0.8 |

| Time to loss of reduction | −0.1 | 0.12 | 0.2 | −0.7 | −0.12 |

| Age | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 |

Fig. 5.

Scatter plot.

There was a symptomatic loss of reduction in one (2%) case from Group II, which occurred at 14 weeks postoperatively, requiring surgical approach and treated as a chronic ACJD using a semitendinosus graft. All patients who practiced sports with use of the upper limb (16 patients) were able to return to the same level of activity prior to injury, except for one patient from Group II, who was a swimmer. There were no significant complications in any of the groups.

Discussion

The high rate of complications associated with the variety of methods described in literature for the treatment of ACJD reflects the inefficiency in restoring the anatomy of the acromioclavicular region. Provisional fixation with pins or cerclage is not recommended, due to the increased incidence of degenerative changes of the acromioclavicular joint, bone erosion, and pin breakage or migration.13 The concept of transfer of the coracoacromial ligament (Weaver-Dunn procedure), with its various modifications, is that such a transfer would withstand tensile forces as the native ligament does. However, it has been proven that the coracoacromial ligament is biomechanically inferior in comparison with the reconstruction with semitendinosus tendon graft, leading to chronic subluxation or dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint in 30% of cases.14

Treatment principle for ACJD cases is reduction of the injured joint and maintenance of this reduction until the soft tissue heals and the distal clavicle stabilizes. Su et al.10 used an anchor in place of a screw, as a modification of the Bosworth technique, and obtained satisfactory results in 11 patients operated due to ACJD. They concluded that this procedure is simple, and anatomically reproduces the coracoclavicular ligaments to provide vertical and horizontal stability in cases of ACJD. The advantages of using anchors instead of subcoracoid ligation include shorter surgical time, which was also demonstrated in the present study, and less risk of nerve and vascular injuries, as it is not necessary to address the medial aspect of the coracoid.15, 16 Furthermore, the new generation of anchors without eyelet has the potential advantage of not having implant material, which can cause breakage of the high-strength wire upon their contact.11

Breslow et al.,17 in a cadaveric study, compared the mechanical stability achieved after coracoclavicular stabilization with the technique of subcoracoid ligature with the suture anchors technique. Although the group with anchors has shown slightly better results, both methods were proven to be statistically similar. The suggested hypothesis was that the ligature has some accommodation of movement in the subcoracoid region, and that it would generate lower stability. Another study, which compared the biomechanical strength of Endobuttons, anchors, and hook plates, demonstrated that the first two have better stability and resistance.18

The loss of initial reduction has been described in the literature; the inaccurate insertion site of the anchors has been the reason pointed out by some authors.9, 10 The present authors believe that the observed loss is more closely related to the quality of scar tissue, occurring when there is a rupture of the wires due to fatigue and this tissue has to assume the role of joint stabilizer; it is important to note that this is a hypothesis, and to date there are no studies that corroborate it. However, this was observed in the new surgical approach to the single case that required another surgery due to symptomatic loss of reduction. In the present study, we observed that in all cases from the four groups, there was a loss of reduction compared to what was achieved in the immediate postoperative period; this loss of reduction occurred around the 13th week. The authors also hypothesized that the quality of scar tissue is directly determined by the stability achieved by the fixation method, which was verified in the present study, as the smallest losses, in a statistically significant manner, were observed precisely in the methods that presented greater stability in biomechanical studies.17, 18 As some loss of reduction is expected to occur, to a greater or lesser degree, the authors sought to perform a hyper-reduction in all cases in the present study. A strong correlation between the immediate post-operative measurement and the final measure was observed. The greater the hyper-reduction, the smaller the final radiographic measurement of the coracoclavicular region. Thus, the final result was esthetically and radiologically satisfactory, without impacting the functional result. Studies in the literature show that the loss of reduction does not affect the clinical outcome of the treatment.19, 20, 21 This was also observed in the present study. Only one patient had symptomatic loss of reduction and required a new surgical procedure.

Conclusion

Surgical treatment with anchors without eyelet showed excellent clinical and radiological results, with loss of reduction comparable to the arthroscopic method with two tightropes, and significantly lower than methods of subcoracoid ligature with four high-strength wires and arthroscopy with one tightrope. Surgical time for this method was significantly lower than the subcoracoid ligature, with the possibility of a small surgical incision of approximately 2 cm. Regardless of the technique used, a hyper-reduction of the joint should always be attempted, aiming for more favorable radiographic and esthetic results.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Hospital Orthoservice, Grupo de Ombro e Cotovelo, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Laprade R.F., Surowiec R.K., Sochanska A.N., Hentkowski B.S., Martin B.M., Engebretsen L. Epidemiology, identification, treatment, and return to play of musculoskeletal-based ice hockey injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(1):4–10. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch T.S., Saltzman M.D., Ghodasra J.H., Bilimoria K.Y., Bowen M.K., Nuber G.W. Acromioclavicular joint injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and management. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2904–2908. doi: 10.1177/0363546513504284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockwood C.A., Jr., Green D.P., Bucholz R.W., Heckman J.D. 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1996. Fractures in adults. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockwood C.J., Williams G.D.Y. Disorders of the acromioclavicular joint. In: Rockwood C., Matsen F.I., editors. The shoulder. 2nd ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1998. pp. 483–553. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gumina S., Carbone S., Postacchini F. Scapular dyskinesis and SICK scapula syndrome in patients with chronic type III acromioclavicular dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(1):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kibler W.B., McMullen J. Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(2):142–151. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sethi G.K., Scott S.M. Subclavian artery laceration due to migration of a Hagie pin. Surgery. 1976;80(5):644–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lädermann A., Gueorguiev B., Stimec B., Fasel J., Rothstock S., Hoffmeyer P. Acromioclavicular joint reconstruction: a comparative biomechanical study of three techniques. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi S.W., Lee T.J., Moon K.H., Cho K.J., Lee S.Y. Minimally invasive coracoclavicular stabilization with suture anchors for acute acromioclavicular dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):961–965. doi: 10.1177/0363546507312643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su E.P., Vargas J.H., 3rd, Boynton M.D. Using suture anchors for coracoclavicular fixation in treatment of complete acromioclavicular separation. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2004;33(5):256–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavinatto L.M., Iwashita R.A., Ferreira Neto A.A., Benegas E., Malavolta E.A., Gracitelli M.E.C. Tratamento artroscópico da luxação acromioclavicular aguda com âncoras. Acta Ortop Bras. 2011;1999(3):141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rockwood C.A., Jr., Matsen F.A., 3rd, Wirth M.A., Lippitt S.B., Fehringer E.V., Sperling J.W. 4th ed. Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2009. Rockwood the shoulder. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazet R.J. Migration of a Kirschner-wire from the shoulder region into the lung: report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1943;25:477–483. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver J.K., Dunn H.K. Treatment of acromioclavicular injuries, especially complete acromioclavicular separation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(6):1187–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumgarten K.M., Altchek D.W., Cordasco F.A. Arthroscopically assisted acromioclavicular joint reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(2):228.e1–228.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellmann M., Zantop T., Petersen W. Minimally invasive coracoclavicular ligament augmentation with a flip button/polydioxanone repair for treatment of total acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(10) doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.12.015. 1132.e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslow M.J., Jazrawi L.M., Bernstein A.D., Kummer F.J., Rokito A.S. Treatment of acromioclavicular joint separation: suture or suture anchors? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(3):225–229. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.123904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nüchtern J.V., Sellenschloh K., Bishop N., Jauch S., Briem D., Hoffmann M. Biomechanical evaluation of 3 stabilization methods on acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1387–1394. doi: 10.1177/0363546513484892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser-Moodie J.A., Shortt N.L., Robinson C.M. Injuries to the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(6):697–707. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B6.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simovitch R., Sanders B., Ozbaydar M., Lavery K., Warner J.J. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(4):207–219. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200904000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon Y.W., Iannotti J.P. Operative treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries and results. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22(2):291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(03)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]