Abstract

Retinal vascular injury is a major cause of vision impairment in ischemic retinopathies. Insults such as hyperoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to this pathology. Previously, we showed that hyperoxia-induced retinal neurodegeneration is associated with increased polyamine oxidation. Here, we are studying the involvement of polyamine oxidases in hyperoxia-induced injury and death of retinal vascular endothelial cells. Newborn C57BL6/J mice were exposed to hyperoxia (70% O2) from postnatal day (P) 7 to 12 and were treated with the polyamine oxidase inhibitor MDL 72527 or vehicle starting at P6. Mice were sacrificed after different durations of hyperoxia and their retinas were analyzed to determine the effects on vascular injury, microglial cell activation, and inflammatory cytokine profiling. The results of this analysis showed that MDL 72527 treatment significantly reduced hyperoxia-induced retinal vascular injury and enhanced vascular sprouting as compared with the vehicle controls. These protective effects were correlated with significant decreases in microglial activation as well as levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. In order to model the effects of polyamine oxidation in causing microglial activation in vitro, studies were performed using rat brain microvascular endothelial cells treated with conditioned-medium from rat retinal microglia stimulated with hydrogen peroxide. Conditioned-medium from activated microglial cultures induced cell stress signals and cell death in microvascular endothelial cells. These studies demonstrate the involvement of polyamine oxidases in hyperoxia-induced retinal vascular injury and retinal inflammation in ischemic retinopathy, through mechanisms involving cross-talk between endothelial cells and resident retinal microglia.

1. Introduction

Neuro-vascular damage to retina is one of the major causes of vision impairment in blinding diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). ROP is a devastating disease in premature infants and a major cause of childhood vision impairment, whereas the other mentioned ischemic retinopathies affect working age adults. These retinopathies are characterized by microvascular degeneration, neuronal death, abnormal intravitreal neovascularization, and have recently been reported to be associated with neuro-inflammatory responses [1–3]. Various insults including hyperoxia, oxidative stress, and inflammation are believed to trigger degeneration of the retinal vasculature in early phases of ROP. The mechanistic links between these insults and the retinal vascular degeneration are not yet clear.

Inflammation is an underlying component of a variety of central nervous system (CNS) disorders and their associated pathology. Studies have shown a link between upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and retinal vascular damage, but the underlying mechanisms are not yet clear [4,5]. Microglia are the primary resident immune cells of both brain and retina. They associate closely with the vasculature and play a key role in retinal vascular development [6,7], remodeling [8] and repair [9]. Activated microglia can cause tissue damage by the production of an array of cytotoxic factors including superoxide, nitric oxide [10,11], TNF-α [12,13], andIL1-β [14]. Microglia become activated in response to diverse stimuli, including neuronal damage, disease proteins and environmental toxins. Microglial activation is evident in patient samples and/or disease models of diabetic retinopathy [15], glaucoma [16,17], ischemia reperfusion injury [18], oxygen-induced retinopathy [14,19,20] and other ocular diseases [21,22]. Thus, it is important to determine the mechanisms by which microglia become activated and induce cellular damage during hyperoxia.

Hyperoxia induces many changes in the retina, however, the series of events that trigger vascular degeneration are not clearly defined. During hyperoxia, expression of HIF-1α, VEGF and other angiogenic factors is greatly reduced in the retina, which prevents vascular regrowth and repair [23]. Moreover, inflammation is believed to play a key role in inhibiting vessel growth. TNF-α inhibition has shown to promote revascularization during the hypoxic phase of OIR [24], suggesting a role for inflammation in governing revascularization. One of the major sources of inflammation in the retina are the resident microglia cells, which are normally present in great numbers. Their activity is greatly enhanced following injury/insult. As a result, they secrete a number of pro and anti-inflammatory factors [14]. However, it is unclear how hyperoxia triggers microglial activation, induces inflammation and further promotes vascular injury.

Polyamines are involved in various cellular functions such as cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Alterations in polyamine metabolism have been demonstrated to be involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease [25], Parkinson's disease [26], cancer [27–29], traumatic brain injury [30], and ischemic brain damage [31,32]. Activation of polyamine oxidases (PAOs) including spermine oxidase (SMO) and acetyl polyamine oxidase (APAO) leads to formation of cytotoxic aldehydes, acrolein and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which can damage DNA, RNA, proteins and lipids [33]. In addition, studies have shown that PAOs and acrolein can serve as novel biomarkers for diagnosis of cerebral stroke [34,35]. Our studies recently highlighted the role of polyamine metabolism in causing retinal neuronal degeneration [36]. However, the role of PAO in retinal vascular injury is unknown.

A widely used model for studies of retinal vascular injury is the oxygen induced retinopathy (OIR) model, where neonatal mice or rats are exposed to hyperoxia [23,37]. Our studies showed that hyperoxia-induced neuronal degeneration is associated with significant increase in function of PAOs and expression of SMO. This was associated with increases in spermidine and H2O2 and decreases in spermine, suggesting a significant role for SMO in the neuronal injury [36]. Studies in transgenic mice overexpressing SMO in neonatal cortex have shown increased levels of H2O2 and increased sensitivity to excitotoxic brain injury [38]. Studies using a rat model of cerebral ischemia have shown that inhibition of PAOs using MDL 72527 significantly reduced brain edema, ischemic injury volume and polyamine levels [39]. Our previous studies in the OIR model have demonstrated that inhibition of PAO function using MDL 72527 significantly reduced hyperoxia-induced neuronal cell death [36]. However, the involvement of PAOs function in hyperoxia-mediated retinal vascular degeneration is yet to be elucidated. In the current study, using OIR model of ischemic retinopathy, we sought to determine the involvement of PAO function using an inhibitor MDL 72527, in microglial activation, inflammation and retinal vascular injury.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

MDL 72527 (N1,N4-bis-2,3-butadienyl-1,4-butanediamine dihydrochloride), hydrogen peroxide, poly D Lysine and Triton X-100 were purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Normal goat serum (NGS) was received from Jackson Immune Research (West Grove, PA, USA). Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) was obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was a product of Gemini bioproducts (West Sacramento, CA USA) and RIPA Lysis Buffer from Millipore (Billerica, MA USA). Rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVECs) were purchased from Cell Applications, Inc., San Diego, CA USA.

2.2. Treatment of animals

All procedures with animals were performed in accordance with and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (Animal Welfare Assurance no. A3307-01). A mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) was utilized as previously described [23]. Briefly, at postnatal day 7 (P7), C57/BL6J mouse (Jackson Laboratories) pups along with nursing mothers were placed in 70% oxygen. To study the role of PAOs in retinal vascular injury, we administered a potent inhibitor of PAOs, MDL 72527 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (39 mg/kg/day in 0.9% saline, i.p.) and vehicle (0.9% saline) daily from P6 to P12. The dosage of MDL 72527 was determined through pilot experiments with varying doses including 10 mg/kg/day, 20 mg/kg/day, 40 mg/kg/day and 100 mg/kg/day. The lower doses (10 and 20 mg/kg/day) did not prove effective in abrogating vascular injury and higher dose (100 mg/kg/day) worsened the vascular injury. However, the dose of 40 mg/kg/day proved effective in reducing hyperoxia-induced vascular injury. In our previous study, we used 39 mg/kg/day based on animal body weight calculations [36], therefore, we decided to use the same dose in this study. They were returned to room air (21% oxygen) at different time points (P9 to P12) and immediately sacrificed for collection of retinas. Age matched pups maintained in normoxia were used as controls as needed. To minimize the effects of hypoxia, pups were sacrificed immediately when they were taken from hyperoxia chamber, samples were collected, and processed for respective experiments.

2.3. Immunostaining of vessels & microglia in whole-mount retinas

Eyes were enucleated at various time points and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The cornea, sclera, lens, vitreous, and hyaloid vessels were removed and four radial incisions were made to allow flattening of the retina. Retinas were blocked and permeabilized in PBS containing 10% NGS and 1% Triton-X-100 for 30 min. Retinas were then stained with Iba-1 (1:400, Wako, Richmond, VA) for 2 h at 37 °C, followed by Alexa594-labeled Griffonia simplicifolia Isolectin B4 (1:200) and secondary antibody Alexa-Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit (1:500) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4 °C. Retinas were washed in PBS four times, 15 min each. Retinas were flatmounted in mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and examined by confocal microscopy. Areas of vaso-obliteration were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) as previously described [23]. To perform vessel sprouting analysis, 20× confocal images were acquired and vessel sprouts were examined at the boundary between vascular and central avascular zone (from 3 to 6 images from different zones from each retina) as previously described [40]. Microglial activation was assessed by acquiring 20× confocal images. The number of microglia were examined in the mid-central retina (at the boundary between vascular and central avascular zone) at the superficial layer (12 um thickness) close proximity to vessels. Serial images were acquired using confocal microscope and “z-stacks” were generated. We acquired 3–6 images/retina from central retinal zones, including each quadrant of the retina. The number of activated and resting microglia per field of view were identified based on their morphology, and activated microglia were quantified manually.

2.4. Immunofluorescence on retinal sections

Eyes were removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (overnight, 4 °C), equilibrated in 30% sucrose and embedded in OCT compound. Frozen sections (10 µm) were permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100 (20 min) and blocked in 10% NGS containing 1% BSA (1 h). Sections were incubated overnight in Alexa594-labeled G. simplicifolia Isolectin B4 (1:200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or Iba1 (1:400, Wako, Richmond, VA) at 4 °C, followed by reaction with Alexa flour conjugated secondary antibody (1:500, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were washed with PBS, mounted with mounting medium and examined under Zeiss fluorescent and confocal microscopes.

2.5. TUNEL assay

Tissue sections were prepared as described above. Retinal cell death was studied using TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) assay using fluorescein in situ cell death detection kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Fluorescent images were taken to identify TUNEL positive cells. TUNEL positive endothelial cells on retinal sections were quantified by manually counting TUNEL cells co-localized with Isolectin B4 (and not for Iba1), on the GCL, from optic nerve head to retinal periphery. The number was multiplied by two to represent total number of TUNEL positive endothelial cells on the GCL per retinal section.

2.6. Multiplex assay for cytokine/chemokine detection

Whole retinal lysates were prepared from a pool of two retinas/tube. The pooled retinas were submerged in cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4 with 0.2% Triton-X-100 and protease inhibitors) and homogenized into a clear solution. Samples were centrifuged at 4 °C and 14,000 RPM for 30 min. Supernatants were collected and diluted 15-fold and protein levels were measured using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Grand Island, NY). Approximately 4.5 ug/uL of protein was used to assay for cytokine/chemokine levels using Milliplex MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine 32-plex assay (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). The following cytokines/chemokines were assayed: Eotaxin, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IP-10, KC, LIF, LIX, M-CSF, MCP-1, MIG, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2, RANTES, TNF-α, and VEGF. The cytokines/chemokines with the highest changes in the expression levels were selected and represented in a graph.

2.7. Primary retinal microglia culture

Microglia were isolated from retinas of newborn Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats according to previous methods with some modifications [41]. Retinas were dissected from newborn SD rat pups (within 24 h). Retinas were collected into 1 × PBS and washed with ice-cold 1 × PBS. They were digested with 0.5% trypsin for 3 min, followed by trypsin inactivation with DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) plus 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin solution (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). The retina tissue was digested and mixed by mechanical dissociation using glass pipette several times until cells were dispersed. Cells were filtered through a 40 µm nylon-mesh filter, collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 10 min, re-suspended in culture medium, and plated onto low profile T100 cell culture flasks (Corning, Corning, NY) at a density of 10 × 106 cells/flask. The flasks were maintained in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The medium was changed after the fourth day and then once every 3 days. After ~2 weeks, microglia cells were harvested by shaking the flasks at 100 rpm for 3 h, at 37 °C and 5% CO2, followed by collection of detached cells and centrifugation in culture media. Cells were counted and frozen for future experiments. Immunofluorescence studies confirmed a nearly 95% purity of cultured microglia labeled with microglia-specific marker Iba-1.

2.8. Microglia treatment with hydrogen peroxide

Microglia were plated in DMEM/F12 plus 10% FBS and 1% P/S for 24 h in poly-d-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated plates at density of 0.5 million/mL, and then in serum-free, low-protein medium (Corning, Corning, NY) for 12 h. They were stimulated with 50 uM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h and then media was changed. Cells were then kept in the new media for additional 5 h. Upon completion of the treatment, conditioned-media was collected for additional experiments and cells were fixed for imaging studies.

2.9. Microglia cell imaging

Activated retinal microglia (using H2O2) were washed with PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then washed again with PBS. Fixed cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 (20 min) and blocked in 10% normal goat serum containing 1% BSA (1 h). Cells were incubated in rabbit Iba-1 (1:500, Wako, Richmond, VA) and rat CD68 (1:100, ABD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in secondary antibodies, Alexa-Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa-Fluor 594 goat anti-rat (1:500, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

2.10. Primary rat brain endothelial cell culture and treatments

Rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVECs) were purchased (Cell Applications, Inc., San Diego, CA) and sub-cultured according to manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, T-75 flasks were coated with Attachment Factor Solution (Cell Applications), cells were seeded and allowed to grow overnight in growth medium (Cell Applications) and subcultured when 80% confluent. Passage 5–7 cells were used for experiments. RBMVECs were treated with conditioned-media (400 uL) from activated retinal microglia for 24 h. Thereafter, cells were washed and lysed for Western blotting to study cell stress signals.

2.11. Western blotting

Cultured cells were homogenized in a RIPA Lysis Buffer (Millipore, Billerica, MA) supplied with phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 1 mM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein samples (20 µg) were subjected to 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and the membrane was blocked (5% milk) and incubated with primary antibodies against rabbit polyclonal smox (1:500, Proteintech, Radnor, PA), rabbit p-JNK/SAPK (1:500), rabbit t-JNK/SAPK (1:1000), rabbit p-P38 (1:1000), rabbit t-P38 (1:1000), cleaved caspase-3 (1:500) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and mouse β-actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000, GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). Immunoreactive proteins were detected using the chemiluminescence (ECL) system (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA).

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±SEM. Group differences were evaluated by using Student's t-test or one way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post-hoc test for statistical analysis. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Animal studies were performed in groups of 6–18 mice. Tissue culture studies were performed in groups of 3–5 cultures and each experiment was repeated three times.

3. Results

We have shown previously that retinal polyamine oxidase is increased in response to hyperoxia and is critically involved in retinal cell death and neurodegeneration in mouse OIR model. Further, treatment using MDL 72527 (a SMO/APAO inhibitor) markedly reduced retinal cell death in the OIR retina [36]. In the current study we investigated whether inhibition of PAO using MDL 72527 reduces hyperoxia-mediated retinal vascular injury and examined the mediators involved in this process.

3.1. MDL 72527 treatment reduces retinal vascular injury

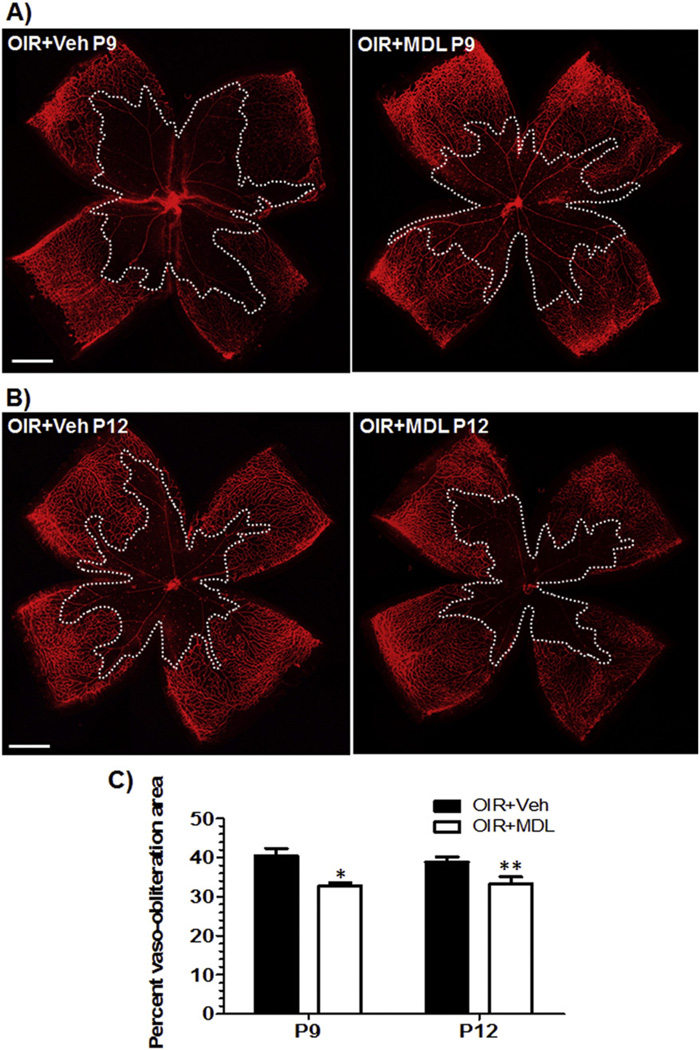

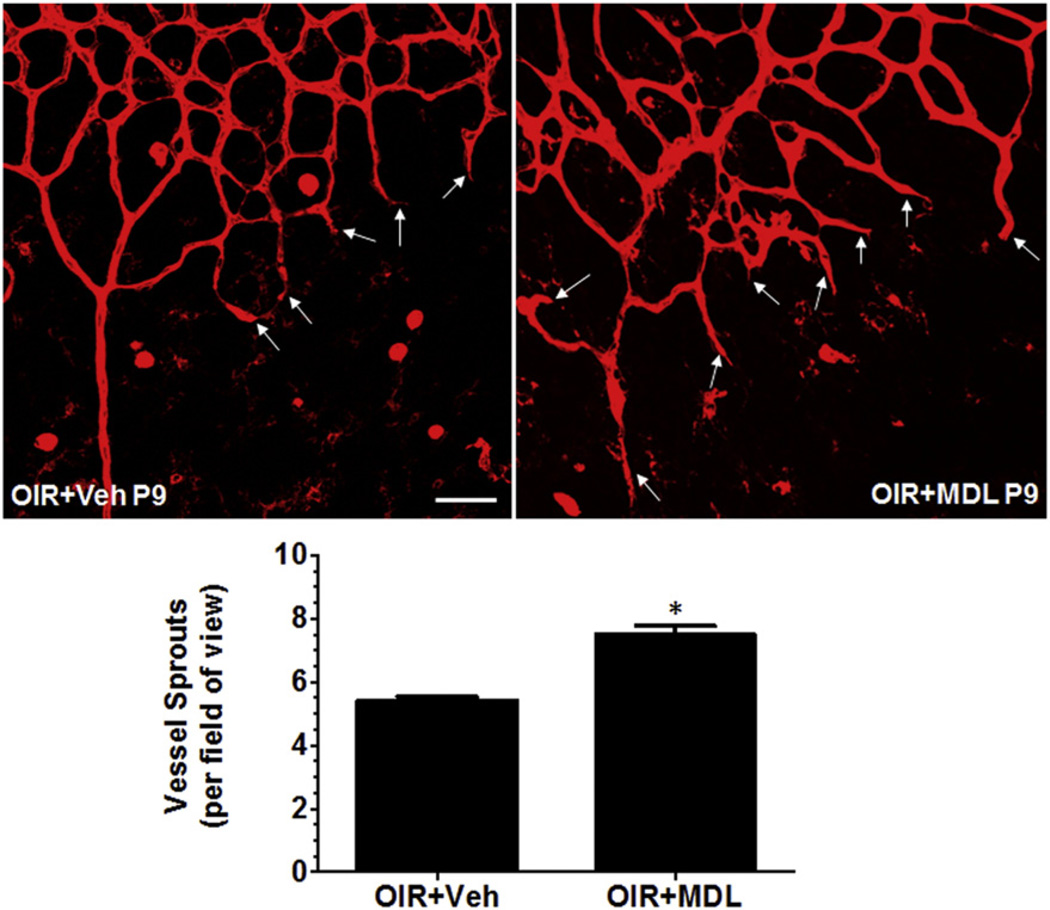

In order to study the involvement of PAOs in retinal vascular damage during hyperoxia, we utilized the OIR mouse model, administered polyamine oxidases inhibitor MDL 72527 from P6 to P12 (39 mg/kg/day) and assessed retinal vascular structure at different stages of hyperoxia, P9 and P12. We then performed flatmounting and visualized the blood vessels using Isolectin B4 staining, and analyzed vaso-obliteration area and vessel sprouts using NIH ImageJ software. It has been well demonstrated that OIR treatment induces vascular degeneration in retina [23]. Our studies showed that MDL treatment significantly reduced the area of vaso-obliteration in hyperoxia-treated retina as compared with the vehicle control on P9 (Fig. 1A). Similar results were observed when vaso-obliteration was studied at P12 (Fig. 1B). Quantification of avascular area demonstrated a significant reduction in retinas isolated from MDL treated animals, compared to vehicle treatment, at both P9 (p < 0.01) and P12 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C), suggesting that PAO function is involved in hyperoxia mediated retinal vascular damage. We observed no differences between the two groups on P9 and P12, which indicates that the maximal protection is observed at P9 and it is sustained until P12. In addition, we analyzed the vascular fronts for new vessel sprouts, which normally promote vascular growth toward the avascular regions of the retina, at the boundary between vascular and central avascular zone. This analysis showed a significant increase in number of sprouts in the MDL treated retinas on P9 compared with the vehicle control (Fig. 2). This data supports the hypothesis that PAO function is involved in preventing revascularization in the retina during hyperoxia.

Fig. 1.

Treatment with MDL 72527 reduces hyperoxia-induced vascular injury in OIR retina. OIR treated mice were given vehicle or MDL 72527 (39 mg/kg/day) from P6 to P12 and sacrificed on either P9 or P12. Retinas were dissected, flatmounted and immunostained with Isolectin B4 (red, blood vessels). Serial images of the superficial layer were taken for each retina at 5× using a fluorescence microscope and merged using photoshop. (scale bar – 500 µm) A) treatment of OIR mice with MDL 72527 reduced degeneration of vessels in the central retina (indicated by reduced vaso-obliteration area within the white borders) on P9 and B) on P12. C) The percent vaso-obliteration area was quantified using ratio of vaso-obliteration area/total retinal area using ImageJ software. OIR mice treated with MDL 72527 showed significant reduction in vaso-obliteration area compared to mice treated with vehicle on P9 and P12. There were no significant differences between the either group on P9 vs. P12 (*p < 0.01 vs. OIR + Veh P9, **p < 0.05 vs. OIR + Veh P12, n = 8–12 retinas, 3 litters of mice).

Fig. 2.

MDL 72527 treatment during hyperoxia promotes vessel sprouting in the OIR retina. OIR treated mice were given vehicle or MDL 72527 (39 mg/kg/day) from P6 to P9 and sacrificed on P9. Retinas were dissected, flatmounted and immunostained with Isolectin B4 (red, blood vessels) and images were taken at 20× (3–6 images/retina at the boundary between vascular and central avascular zone; scale bar – 50 µm) using confocal microscopy. Treatment of OIR mice with MDL 72527 enhances revascularization by promoting new vessel sprouts into the avascular area (shown by white arrows) on P9. The vessel sprouts per field of view were counted manually. OIR mice treated with MDL 72527 had increased numbers of vessel sprouts compared to vehicle group (*p < 0.01 vs. OIR + Veh, n = 7–9 retinas, 3 litters of mice).

3.2. Inhibition of polyamine oxidase limits retinal vascular cell death

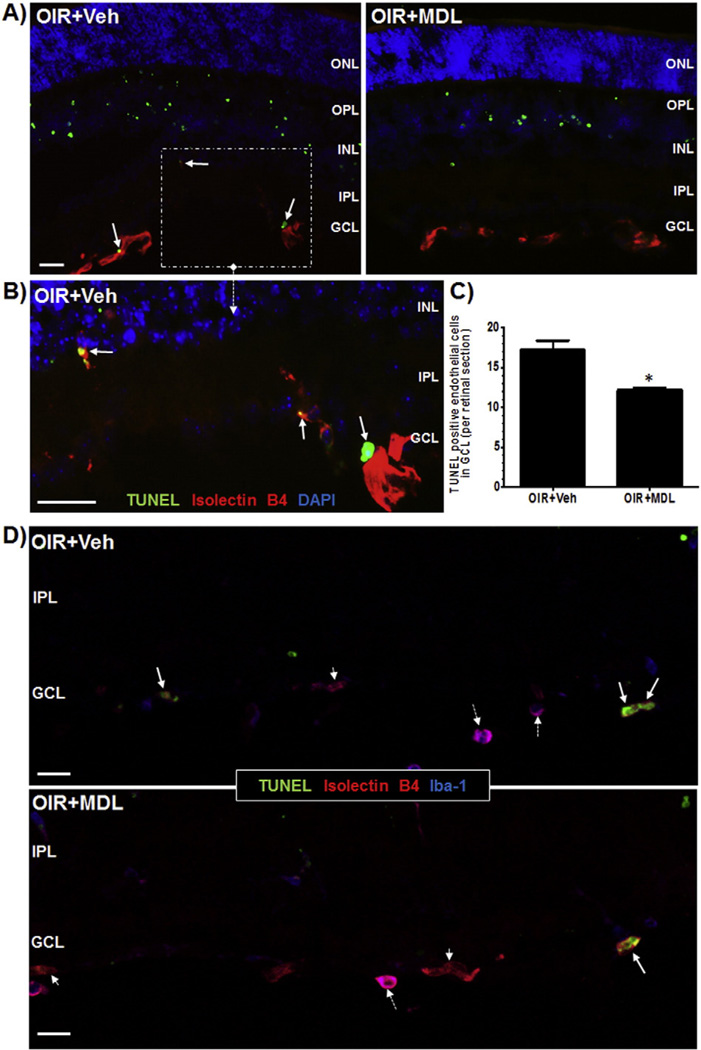

Our previous studies have shown that there is increased cell death in retina in response to hyperoxia as studied by increase in TUNEL positive cells. Further, we have shown that treatment using MDL 72527 significantly reduced OIR-mediated neurodegeneration and retinal cell death [36]. In the current study we further confirmed this observation and also investigated whether hyperoxia causes retinal endothelial cell death. We utilized the OIR mouse model and administered PAO inhibitor MDL 72527 from P6 to P12 (39 mg/kg/day). Analysis using Isolectin B4 immunostaining and TUNEL labeling on retinal sections (P9) demonstrated increased presence of TUNEL positive cells colocalized with Isolectin B4 in retinas of the vehicle-control OIR (Veh + OIR) mice (Fig. 3). Conversely, MDL 72527 treatment reduced TUNEL-positive endothelial cells, suggesting that inhibition of PAO during hyperoxia prevents endothelial cell death in OIR retina. Since Isolectin B4 labels some microglia as well, additional immunolabeling studies using Iba1 (marker for microglia) and Isolectin B4 was performed (Fig. 3D) to avoid including any lectin labeled microglia in TUNEL analysis (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Hyperoxia-induced retinal endothelial cell death is reduced in response to MDL 72527 treatment. OIR treated mice were given vehicle or MDL 72527 (39 mg/kg/day) from P6 to P9 and sacrificed on P9. Retinas were dissected and sectioned and cell death was studied using TUNEL assay. Retinas were also co-labeled with Isolectin B4 (red, blood vessels). A) Fluorescent microscopy (20×, scale bar – 10 µm) revealed many more TUNEL-positive cells, including endothelial cells (white arrows) were present in the vehicle-treated retinas, compared to MDL-treated retinas. B) The inset (40×, scale bar – 20 µm) shows magnified view of the TUNEL-positive endothelial cells (white arrows). C) Number of TUNEL positive cells colocalized with Isolectin B4 (negative for Iba1) in the superficial layer (GCL) were quantified manually in retinal sections. The data indicated significantly more TUNEL-positive endothelial cells in the vehicle-treated retinas compared to MDL-treated retinas (shown in graph). D) Confocal images of the GCL from vehicle and MDL treated retinal sections labeled with Iba1, Isolectin B4 and TUNEL showed colocalization of TUNEL positive cells (green) with endothelial cells (red), but not microglia (blue). Full arrow = TUNEL/Isolectin B4; broken arrow = Isolectin B4/Iba-1; small arrow head = Isolectin B4. (20×, scale bar – 20 µm) Representative images are shown from each group. (n = 3–6 retinas) (ONL-outer nuclear layer, OPL-outer plexiform layer, INL-inner nuclear layer, IPL-inner plexiform layer, GCL-ganglion cell layer).

3.3. Polyamine oxidase signaling influences microglial activation/differentiation

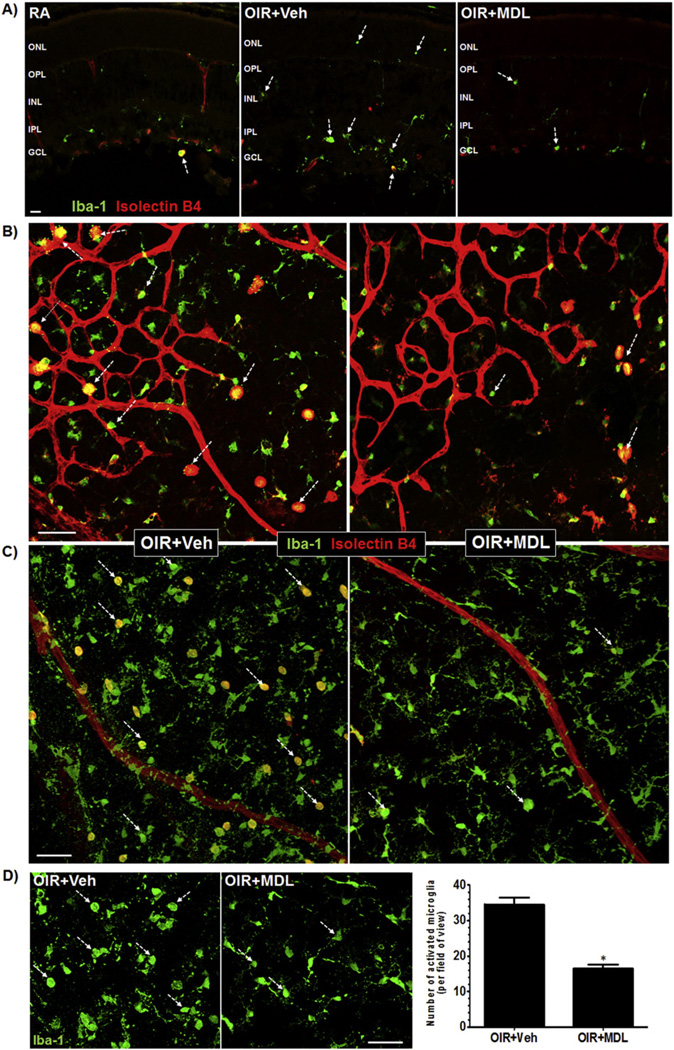

Studies have reported that microglia become activated in OIR injury models [19] and from oxidative insults such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [42,43]. In the previous study, we have shown that H2O2 level is increased in the retina in response to hyperoxia (P9), and is significantly reduced with MDL 72527 treatment [36]. Hence, we investigated the impact of MDL 72527 in OIR-mediated microglial activation. We assessed this by studying the P9 retinal sections and flatmounts, which were stained with Isolectin B4 (marker of blood vessels) and Iba-1 (general marker of microglia). Confocal images were acquired (z-stacks were generated) at the superficial layer near the boundary between vascular and avascular zone, and the avascular areas in the central retina just further from the boundary. This strategy allows us to study microglial phenotype with respect to vascular injury and microglia phenotype in the avascular milieu devoid of vessels. The activation state of microglia is characterized by their large rounded cell body with thick and short dendrites, whereas in the resting state they are highly ramified with long and thin dendrites (Fig. 4A). We observed clear differences in microglial morphology between the two treatment groups exposed to hyperoxia (Fig. 4A–B). Hyperoxia-treated retinas had numerous amoeboid (rounded and activated) microglia and MDL treatment markedly reduced this effect. The microglial phenotype in the MDL-treated retinas was predominantly ramified. Closer examination and quantification of Iba1 positive activated microglia demonstrated a significant reduction in numbers of amoeboid microglia in response to MDL treatment (Fig. 4C–D). This data suggests that MDL attenuates microglial activation in vivo through the regulation of SMO activation in retina. In addition, increased number of activated microglia were present in close proximity to the growing vasculature, both in and around the avascular regions of the retinas of the vehicle-treated mice compared to MDL-treated mice (Fig. 4B). We also observed many more hypertrophic phagocytic macrophages (enlarged in size) near the vascular front in the avascular regions in the vehicle control OIR retinas compared to MDL-treated mice. This suggests an association between microglia/macrophage activation and vascular damage. Altogether, increased PAO function during hyperoxia results in activation of retinal microglia proximal to the blood vessels, which is associated with retinal vascular injury.

Fig. 4.

MDL 72527 treatment during hyperoxia limits retinal microglial activation. OIR treated mice were given vehicle or MDL 72527 (39 mg/kg/day) from P6 to P9 and sacrificed on P9 along with age matched normoxia room-air controls (RA). Retinas were dissected, flatmounted or sectioned and immunostained with Isolectin B4 (red, blood vessels and microglia/macrophages) and Iba-1 (green, both amoeboid and ramified microglia/macrophages). Serial images (20×) of retinal sections and flatmounts were acquired using confocal microscope and “z-stacks” were generated to image superficial retinal layer (12 um thickness). Images were acquired near the boundary between vascular and avascular zone, and the avascular areas in the central retina just beyond the boundary. A) Immunolabeling of retinal cryostat sections using Iba1 and Isolectin B4 antibodies showed marked increases in amoeboid microglia in OIR retina compared to RA retina. MDL treatment reduced amoeboid microglia compared to vehicle treatment, as indicated by reduced Iba-1 expression and increases in ramified microglia (shown by white broken arrows). Representative images are shown for each group (n = 3–5 retinas). (scale bar - 20 µm) (ONL-outer nuclear layer, OPL-outer plexiform layer, INL-inner nuclear layer, IPL-inner plexiform layer, GCL-ganglion cell layer) B) Retinal flatmount analysis showing the presence of numerous activated microglia (shown by white broken arrows) (rounded, amoeboid morphology) in close proximity to the growing vasculature in and around the avascular regions of the OIR + Veh retinas compared to OIR + MDL retinas. Representative images are shown for each group. (n = 12 retinas, 3 litters of mice) (3–6 images/retina from central retinal zones from each quadrant of the retina) (scale bar - 50 µm) C) High magnification confocal images revealed increased differentiation of amoeboid (rounded) microglia to ramified or resting (with processes) microglia (shown by white broken arrows) throughout the MDL-treated retinas compared to vehicle-treated retinas. (scale bar – 50 µm) D) Number of rounded microglia (shown by white broken arrows) from both groups were quantified by manual counting. The images shown are cut-outs of the images from panel C. The data showed significant reduction in number of activated mircoglia in MDL compared to vehicle-treated retinas. (*p < 0.01 vs. OIR + Veh, n = 12 retinas per group, 3 litters of mice) (scale bar - 50 µm).

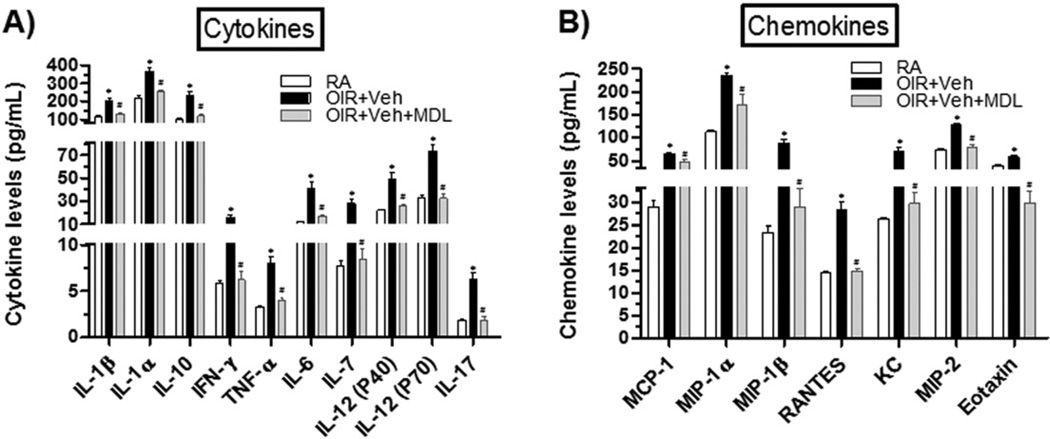

3.4. MDL 72527 treatment reduces retinal inflammation

In order to study the impact of MDL treatment on retinal inflammation in causing vascular injury during hyperoxia, we measured protein levels of an array of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in P8 retinas using a Multiplex assay. In comparison to room-air (RA) control retinas, the vehicle treated OIR retinas contained significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-7, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-17), of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Fig. 5A) and of pro-inflammatory chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1α [macrophage inflammatory protein-1α], MIP-1β, RANTES [Regulated on Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted], KC [keratinocyte chemoattractant], MIP-2, Eotaxin) (Fig. 5B). However, such increases in cytokines and chemokines levels were significantly reduced or normalized in OIR + MDL retinas, suggesting that polyamine oxidase signaling mediates retinal inflammation during hyperoxia.

Fig. 5.

MDL 72527 treatment limits hyperoxia-induced retinal inflammation. OIR treated mice were given vehicle or MDL 72527 (39 mg/kg/day) from P6 to P8 and sacrificed on P8. Age-matched room-air (RA) controls were prepared for comparison analysis. Retinal levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines were assayed using multiplex analysis. A) Levels of several cytokines and B) chemokines were significantly increased in OIR + Veh retinas compared to RA retinas. These increases were significantly reduced or normalized in MDL-treated OIR retinas. Each sample contained two-pooled retinas and each group contained n = 3 samples, giving total of n = 6 retinas/group. (*p < 0.05 vs. RA, #p < 0.05 vs. OIR + Veh, n = 6, 2 litters of mice).

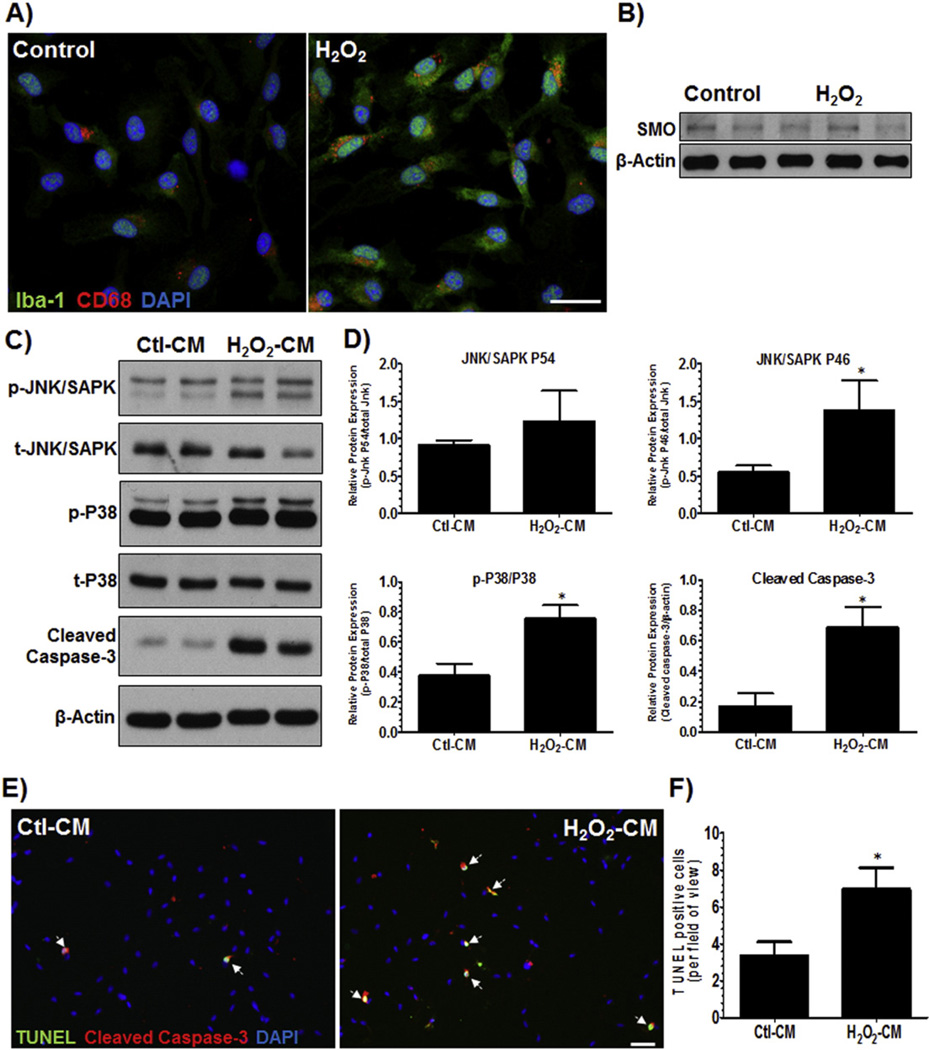

3.5. Activated microglia causes up-regulation of endothelial cell death signals

To confirm the in vivo findings that activated microglia could influence vascular injury, we designed an in vitro cell culture system. Primary cultures of rat retinal microglia were prepared and activated by treatment with hydrogen peroxide, H2O2 (50 uM), for 1 h. The media was changed to normal media after 1 h of exposure to H2O2 and conditioned-medium was collected after 5 h. Since one of the byproducts of SMO enzyme activity is H2O2, we used H2O2 as the activating agent. Activation of microglia was confirmed by immunostaining the cells with Iba-1 (microglia marker) and CD68 antibodies. CD68 is a lysosomal membrane protein and is reported to be increased in microglia following injury. We observed that both Iba-1 and CD68 immunoreactivity were increased following H2O2 treatment (Fig. 6A). Western blotting analysis revealed no significant changes in protein expression of SMO in activated microglial cultures compared to controls (Fig. 6B). To test whether activated microglia can trigger endothelial cell death, we prepared primary cultures of RBMVECs and exposed them to conditioned media from activated microglia (H2O2-CM) for 24 h. Analysis of the protein lysates of RBMVECs revealed that H2O2-CM caused significant increases in activation of stress proteins p-JNK andp-P38 and cell death protein cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 6C–D). Moreover, analysis of TUNEL labeling revealed increased number of co-localized TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 positive cells (Fig. 6E–F). The quantification revealed increased number of TUNEL positive endothelial cells in response to H2O2-CM compared to Ctl–CM. These results confirm that activated microglia induce cell death/stress signals and cause endothelial cell death, further supporting our hypothesis that PAO function mediates microglial activation, which in turn causes vascular endothelial cell death and injury in the OIR retina.

Fig. 6.

Activated microglia induce endothelial cell death. A) Primary cultures of rat retinal microglia were prepared and activated by treatment of H2O2 (50 uM). The media was changed to normal media after 1 h of exposure to H2O2 and conditioned-medium was collected after 5 h. A) Activation of microglia was confirmed by immunostaining the cells with Iba-1 (general microglia marker) and CD68 (lysosomal membrane protein, a marker of microglia activation) antibodies. High-resolution confocal images (20×) revealed that both Iba-1 and CD68 immunoreactivity were increased following H2O2 treatment. (Scale bar – 50 µm) B) Western blotting analysis of lysates from control and activated microglia cells showed no significant changes in expression of SMO C) Primary cultures of rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (RBMVECs) were prepared and treated with conditioned-medium from the activated microglia (H2O2-CM) for 24 h. Western blot analysis revealed that H2O2-CM caused significant increases in stress proteins (p-JNK, p-P38) and cell death protein (cleaved caspase-3), compared to RBMVECs treated with conditioned-medium from non-activated microglia (Ctl-CM). (Representative blots from 3-independent experiments) D) Quantification of the Western blots showed significant increases in p-JNK/SAPK P46, p-P38/P38 and cleaved caspase-3/β-Actin. (*p < 0.05 vs. Control, n = 4–5, averages of 3-independent experiments). E) RBMVECs were fixed and cell death was studied using TUNEL assay (green). Cells were also co-labeled with cleaved caspase-3 (red). Fluorescent microscopy (20×, scale bar – 10 µm) and quantification revealed more TUNEL-positive endothelial cells (white arrows) in the RMG-CM-treated cells, compared to control cells. TUNEL-positive cells were counted from total of 4–6 images per sample. (Representative images are shown) (*p < 0.05 vs. Control, n=3).

4. Discussion

In the present study we report for the first time the role of polyamine oxidases in hyperoxia-induced vascular injury during OIR, and inhibition of polyamine oxidation as a novel target for ROP treatment. Currently, therapies to treat ischemic retinopathies are very limited. Hyperoxia is commonly administered to premature infants to protect their immature lungs, but it can be damaging to the developing microvessels of the retina. Therefore, better targeted-therapies are needed to protect the retinal vessels. The data presented here elucidates the role of polyamine oxidases in causing retinal vascular injury during hyperoxia treatment. PAOs are potential source of oxidative stress as they are capable of producing toxic byproducts including amino aldehyde, acrolein and H2O2 [33]. While the function of PAOs is partially defined in brain injuries, stroke and cancer, its contribution to retinal vascular injury is completely unknown. Previously, we showed that increased polyamine oxidation is responsible for hyperoxia-mediated neurodegeneration in retina [36]. Here, we are providing evidence that polyamine oxidation has an impact in causing retinal inflammation and vascular injury, by a mechanism involving activation of microglia.

Polyamines are essential for cell growth, proliferation and differentiation. It is reported that polyamines are potentially involved in neuronal firing and transmitter release, as well as metabolic and electrophysiological processes [44]. However, alterations in polyamine metabolism have been reported in neurodegenerative injuries including ischemic and traumatic brain injuries [32,45]. Our previous studies showed that levels of spermidine were increased and spermine levels were reduced, and levels of both acetylated spermidine and spermine were reduced in OIR compared to control animals during hyperoxia-mediated neurodegeneration. This implied that oxidation of polyamines is increased and likely contributes to neuronal cell death [36]. This was further confirmed by data showing increased expression of spermine oxidase in inner retinal neurons during hyperoxia. Studies presented here show that PAO function is also critically involved in vascular degeneration and injury.

There is no specific inhibitor available for differential blockade of blocking SMO or APAO function. MDL 72527 is a common competitive irreversible inhibitor of both SMO and APAO [39,46]. Studies have shown that inhibition of PAOs using MDL 72527 significantly reduced brain edema, ischemic injury volume and polyamine levels in a rat model of cerebral ischemia [33,39]. Furthermore, blockade of the polyamine inter-conversion pathway using MDL 72527 was found to be neuroprotective against edema and necrotic cavitation after traumatic brain injury [39]. MDL 72527 has also been shown to reduce oxidative stress in various models of cancer [29,47,48]. The reactive aldehydes and H2O2 released during polyamine oxidation are capable of damaging RNA, DNA, proteins and membranes. This oxidative damage can lead to apoptosis and DNA damage may result in transformation, carcinogenesis and metastatic disease [33]. In our system, treatment with MDL 72527 must be blocking the oxidation of spermine and/or spermidine, and thus reducing the formation of H2O2 and other toxic aldehydes, thereby causing a reduction in oxidative stress in the OIR retina.

Vascular injury in response to hyperoxia has been reported in ROP patients [49,50] and animal models [50,51]. Our studies using the OIR mouse model showed increased vaso-obliteration at both P9 and P12 and decreased vessel sprouting at P9 with hyperoxia treatment. However, blockade of PAOs activity using MDL 72527 reduced vaso-obliteration and improved vessel sprouting during hyperoxia. It is known that the central retinal vasculature in mice subjected to hyperoxia begins to regrow slowly after two days of oxygen exposure, possibly due to the need for oxygen in the hypoxic central area [52]. Our studies here show that this vascular regrowth is significantly enhanced with the MDL treatment, suggesting that PAO inhibition prevents further vessel loss and promotes revascularization during hyperoxia.

It is believed that the mechanisms associated with vaso-obliteration and cell death during hyperoxia involve suppression of HIF-1α, VEGF and other angiogenic factors [53,54]. Studies also indicate that TNF-α inhibition facilitates revascularization during the hypoxic phase of OIR [24], which suggests that the revascularization angiogenic response is governed by inflammatory mediators. Microglia are the primary resident immune cells in the retina. They become activated upon an insult and secrete a number of inflammatory factors [55,56]. Over-activation of microglia results in increased production of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, which are reported to be increased in patients [57] and animals [19, 58] with ischemic retinopathies. We believe that activation of PAO plays a significant role in microglial activation in OIR retina, and is one of the major mechanisms causing vascular damage. Our previous studies showed that SMO is localized primarily in retinal neurons and its expression is increased in response to hyperoxia. In addition, blockade of PAO using MDL 72527 reduced OIR-induced increases in H2O2 levels in the retina [36]. It is known that microglia cells are activated and their migration is enhanced by H2O2 in vitro [42,43]. In the current study, we speculated that, in response to hyperoxia insult, PAO activation causes increased oxidative stress (through increases in H2O2 levels) in retina leading to microglial activation, which would cause inflammation, slow the revascularization process and promote cell death. Our studies clearly indicate that microglia become activated during hyperoxia phase and differentiate from resting or ramified to amoeboid morphology. However, MDL 72527 treatment reduced activation of microglia as indicated by preservation of their ramified morphology.

The close proximity of microglia to the retinal vasculature, as observed in our studies, can have an impact on revascularization and endothelial cell death. Microglia are dynamic in nature and are involved in cross-talk with vessels and neighboring cells. In a model of sepsis, increased numbers of microglia cells were present in the central retinal zones at the vascular fronts and were seen taking part in vascular anastomosis [59]. In a rat model of ischemic retinopathy, it was reported that retinal microglia are activated to produce IL-1β, TNF-α and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and induce microvascular injury. Furthermore, inhibition of IL-1β activity decreases retinal vaso-obliteration and promotes revascularization in rats subjected to 80% hyperoxia [14]. In our study, the increased presence of activated microglia in the vehicle retinas suggested increased phagocytic activity and inflammation, compared to predominantly the ramified phenotypes in MDL retinas, which was correlated with enhanced revascularization. These studies highlight the major contribution of activated microglia in influencing retinal vascular injury and inflammation during hyperoxia and further justify our hypothesis that PAOs mediate vascular injury in relation to microglial activation.

Hyperoxia increased expression of major pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70)) and chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, KC, MIP-2). This cytokine/chemokine expression was normalized by MDL treatment. Studies by others have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6 are increased in serum, vitreous and retinas of patients and animals with ischemic retinopathy [60–63]. In addition, IL-10 and IL-12 levels are increased in STZ-induced diabetic rats [64]. IL-12, which is a multifunctional cytokine, inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo [65]. It is possible that IL-12 in the OIR retina inhibits the revascularization process during hyperoxia. Increases in IL-10 levels, which is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, in our and others' studies can be attributed to a protective feedback reaction to limit inflammatory events. It has been postulated that the IL-10 response is elevated when there is a preceding inflammatory response to cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12, IL-23 and/or IL-27 [66]. Therefore, reduced levels of IL-10 with MDL treatment could be due to the lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines preceding the IL-10 induction. In our studies, both IL-10 and IL-12 levels were reduced with the MDL-treatment and this correlated with reduced inflammation and enhanced revascularization during OIR. IL-1β generated by microglia contribute to microvascular degeneration in a rat model of OIR [14]. To this date, there are no studies reporting the expression of the above cytokines and chemokines during hyperoxia in a single study. It is plausible that the source of above listed cytokines during hyperoxia is the activated microglia cells that we observed in our studies. Microglia secrete and respond to various cytokines and chemokines. Activated microglia express IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6 under stressful conditions [14,67]. Interestingly, astrocytes in vitro and in vivo secrete chemokines in response to various inflammatory stimuli. Treatment of astrocytes with LPS [68] or TNF-α [69] caused increased expression of various chemokines including MCP-1, MIP-1α, RANTES, KC, MIP-2. In an experimental model of multiple sclerosis, astrocytes were found to be the predominant source of MCP-1, MIP-1α and RANTES [70]. It is believed that chemokines secreted by astrocytes at the neurovascular unit in brain may facilitate and recruit the entry of blood cells that home to the injured regions [71]. This theory may apply to retinal microenvironment where astrocytes and endothelial cells, among other retinal cells, make up the neurovascular unit within the blood-retinal barrier and may contribute to further inflammation and vascular injury.

In the current study, we discovered that hyperoxia-induced retinal endothelial cell death in vivo was reduced by MDL treatment. Lange et al. have previously reported, but not shown, endothelial cell death in OIR mice, rapidly after hyperoxia from P7 to P9 [52]. Endothelial cell death has been attributed to apoptotic signals coming from retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). In the present study, we investigated whether activated microglia (in response to H2O2, a byproduct of SMO function) can induce cell death/stress signals in endothelial cells. We do not anticipate SMO activation in microglia, instead in retinal neurons. In our previous study, we observed increased SMO expression primarily in retinal neurons, in response to hyperoxia. It is possible that lower levels of SMO are present in glial cells as well. In the present study, we did not investigate the direct impact of hyperoxia and MDL on microglial activation in relation to endothelial cell death in vitro. A previous study has shown that neither conditioned-media from hyperoxia exposed microglia nor exogenous cytokine treatment is cytotoxic to microvascular endothelial cells [14]. Therefore, we chose the alternative method presented here to study microglial activation in relation to endothelial cell death. H2O2 released into the microenvironment can activate microglia cells, which can secrete inflammatory factors and cause cell death. One of the byproducts of PAO activity is H2O2. Therefore, we directly stimulated RMGs with H2O2, and transferred the conditioned-medium onto endothelial cells. Our in vitro results showed that microglia cells were activated upon stimulation with H2O2, which was confirmed by immunostaining for markers of activation, Iba-1 and CD68. Changes in SMO/PAO expression in primary retinal microglia in response to H2O2 were not observed. The potential cytotoxic effects of H2O2 on RBMVECs were eliminated by changing the medium after just one-hour treatment of RMG with H2O2. In addition, conditioned-media from activated microglia cells increased expression of cell death proteins in endothelial cells and caused cell death. Here, we report for the first time that activation of retinal microglia by H2O2 causes release of factors that cause endothelial cell death in vitro. We have shown in our previous study that cell death signaling pathway is activated in P9 hyperoxic retinas, as shown by increased protein expression of P-JNK/SAPK, FASL, BID and Cytochrome C. In contrast, treatment with MDL significantly reduced the expression of these cell death signaling proteins [36]. Together, the results obtained in our previous study and current studies extend our theory that OIR-induced increases in PAOs activity releases H2O2 in the microenvironment, which is correlated with activation of the surveying microglia cells that influence endothelial cell death and vascular injury, all of which were attenuated by MDL 72527 treatment.

Based on our findings, we speculate that PAO activation mediates endothelial cell death through inflammatory cytokines released by activated microglia. We showed increased microglial activation and levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in vivo. Some of these cytokines are believed to have been secreted by microglia/macrophage cells. Our future studies will elaborate on the mechanisms by which activated microglia-derived factors including cytokines and chemokines contribute to endothelial cell death.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report studying the impact of inhibiting polyamine oxidation, using MDL 72527 treatment in hyperoxia-induced vascular damage in OIR model. We have demonstrated a crucial role of the polyamine oxidation pathway in microglial activation, inflammation and vascular injury associated with OIR. Further, our studies demonstrate the novel role of polyamine oxidases in mediating visual dysfunction through a mechanism involving cross talk between microglia and endothelial cells. Importantly, microglia activated in culture using a catabolite of PAO function causes vascular endothelial cell death. Our study provides a clue on how hyperoxia may cause vascular injury in infants suffering from ROP and thus has great potential for the development of new strategies to prevent disease progression in ischemic retinopathies, as well as other central nervous system pathologies.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Tahira Lemtalsi and Supriya Sridmar for technical assistance with cell culture experiments and multiplex analysis, respectively. This work has been supported by AHA 11SDG7440088 (SPN), Culver Vision Discovery Institute pilot grant VDI00037 (SPN), VA Merit Review Award 1I01BX001233 (RBC); PHS grant R01EY011766 (RBC & RWC).

Footnotes

Transparency document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

Contributor Information

C. Patel, Email: cpatel1@augusta.edu.

Z. Xu, Email: zhxu@augusta.edu.

E. Shosha, Email: eshosha@augusta.edu.

J. Xing, Email: jxing8733@163.com.

R. Lucas, Email: rlucas@augusta.edu.

R.W. Caldwell, Email: wcaldwel@augusta.edu.

R.B. Caldwell, Email: rcaldwel@augusta.edu.

S.P. Narayanan, Email: pnarayanan@augusta.edu.

References

- 1.Joyal JS, Sitaras N, Binet F, Rivera JC, Stahl A, Zaniolo K, Shao Z, Polosa A, Zhu T, Hamel D, Djavari M, Kunik D, Honore JC, Picard E, Zabeida A, Varma DR, Hickson G, Mancini J, Klagsbrun M, Costantino S, Beausejour C, Lachapelle P, Smith LE, Chemtob S, Sapieha P. Ischemic neurons prevent vascular regeneration of neural tissue by secreting semaphorin 3A. Blood. 2011;117:6024–6035. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sivakumar V, Foulds WS, Luu CD, Ling EA, Kaur C. Retinal ganglion cell death is induced by microglia derived pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hypoxic neonatal retina. J. Pathol. 2011;224:245–260. doi: 10.1002/path.2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishida S, Usui T, Yamashiro K, Kaji Y, Ahmed E, Carrasquillo KG, Amano S, Hida T, Oguchi Y, Adamis AP. VEGF164 is proinflammatory in the diabetic retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:2155–2162. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma J, Mehta M, Lam G, Cyr D, Ng TF, Hirose T, Tawansy KA, Taylor AW, Lashkari K. Influence of subretinal fluid in advanced stage retinopathy of prematurity on proangiogenic response and cell proliferation. Mol. Vis. 2014;20:881–893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurada Y, Nakamura Y, Yoneyama S, Mabuchi F, Gotoh T, Tateno Y, Sugiyama A, Kubota T, Iijima H. Aqueous humor cytokine levels in patients with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 2015;53:2–7. doi: 10.1159/000365487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefater JA, 3rd, Ren S, Lang RA, Duffield JS. Metchnikoff's policemen: macrophages in development, homeostasis and regeneration. Trends Mol. Med. 2011;17:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stefater JA, III, Lewkowich I, Rao S, Mariggi G, Carpenter AC, Burr AR, Fan J, Ajima R, Molkentin JD, Williams BO, Wills-Karp M, Pollard JW, Yamaguchi T, Ferrara N, Gerhardt H, Lang RA. Regulation of angiogenesis by a non-canonical Wnt-Flt1 pathway in myeloid cells. Nature. 2011;474:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature10085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang RA, Bishop JM. Macrophages are required for cell death and tissue remodeling in the developing mouse eye. Cell. 1993;74:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritter MR, Banin E, Moreno SK, Aguilar E, Dorrell MI, Friedlander M. Myeloid progenitors differentiate into microglia and promote vascular repair in a model of ischemic retinopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:3266–3276. doi: 10.1172/JCI29683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss DW, Bates TE. Activation of murine microglial cell lines by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma causes NO-mediated decreases in mitochondrial and cellular function. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:529–538. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro BM, do Carmo MR, Freire RS, Rocha NF, Borella VC, deMenezes AT, Monte AS, Gomes PX, de Sousa FC, Vale ML, de Lucena DF, Gama CS, Macedo D. Evidences for a progressive microglial activation and increase in iNOS expression in rats submitted to a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: reversal by clozapine. Schizophr. Res. 2013;151:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borrajo A, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Diaz-Ruiz C, Guerra MJ. J.L. Labandeira-Garcia, Microglial TNF-alpha mediates enhancement of dopaminergic degeneration by brain angiotensin. Glia. 2014;62:145–157. doi: 10.1002/glia.22595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CC, Lin JT, Cheng YF, Kuo CY, Huang CF, Kao SH, Liang YJ, Cheng CY, Chen HM. Amelioration of LPS-induced inflammation response in microglia by AMPK activation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:692061. doi: 10.1155/2014/692061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera JC, Sitaras N, Noueihed B, Hamel D, Madaan A, Zhou T, Honore JC, Quiniou C, Joyal JS, Hardy P, Sennlaub F, Lubell W, Chemtob S. Microglia and interleukin-1beta in ischemic retinopathy elicit microvascular degeneration through neuronal semaphorin-3A. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:1881–1891. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rangasamy S, McGuire PG, Franco Nitta C, Monickaraj F, Oruganti SR, Das A. Chemokine mediated monocyte trafficking into the retina: role of inflammation in alteration of the blood-retinal barrier in diabetic retinopathy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rojas B, Gallego BI, Ramirez AI, Salazar JJ, de Hoz R, Valiente-Soriano FJ, Aviles-Trigueros M, Villegas-Perez MP, Vidal-Sanz M, Trivino A, Ramirez JM. Microglia in mouse retina contralateral to experimental glaucoma exhibit multiple signs of activation in all retinal layers. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:133. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosco A, Crish SD, Steele MR, Romero CO, Inman DM, Horner PJ, Calkins DJ, Vetter ML. Early reduction of microglia activation by irradiation in a model of chronic glaucoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Husain S, Liou GI, Crosson CE. Opioid receptor activation: suppression of ischemia/reperfusion-induced production of TNF-alpha in the retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:2577–2583. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer F, Martin G, Agostini HT. Activation of retinal microglia rather than microglial cell density correlates with retinal neovascularization in the mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. J. Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:120. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kielczewski JL, Hu P, Shaw LC, Li Calzi S, Mames RN, Gardiner TA, McFarland E, Chan-Ling T, Grant MB. Novel protective properties of IGFBP-3 result in enhanced pericyte ensheathment, reduced microglial activation, increased microglial apoptosis, and neuronal protection after ischemic retinal injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:1517–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luhmann UF, Robbie SJ, Bainbridge JW, Ali RR. The relevance of chemokine signalling in modulating inherited and age-related retinal degenerations. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;801:427–433. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3209-8_54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couturier A, Bousquet E, Zhao M, Naud MC, Klein C, Jonet L, Tadayoni R, de Kozak Y, Behar-Cohen F. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor acts on retinal microglia/macrophage activation in a rat model of ocular inflammation. Mol. Vis. 2014;20:908–920. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, Chen J, Dennison RJ, Krah NM, Seaward MR, Willett KL, Aderman CM, Guerin KI, Hua J, Lofqvist C, Hellstrom A, Smith LE. The mouse retina as an angiogenesis model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:2813–2826. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardiner TA, Gibson DS, de Gooyer TE, de la Cruz VF, McDonald DM, Stitt AW. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha improves physiological angiogenesis and reduces pathological neovascularization in ischemic retinopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:637–644. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62284-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue K, Tsutsui H, Akatsu H, Hashizume Y, Matsukawa N, Yamamoto T, Toyo'oka T. Metabolic profiling of Alzheimer's disease brains. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2364. doi: 10.1038/srep02364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paik MJ, Ahn YH, Lee PH, Kang H, Park CB, Choi S, Lee G. Polyamine patterns in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2010;411:1532–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amendola R, Bellini A, Cervelli M, Degan P, Marcocci L, Martini F, Mariottini P. Direct oxidative DNA damage, apoptosis and radio sensitivity by spermine oxidase activities in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1755;2005:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cervelli M, Bellavia G, Fratini E, Amendola R, Polticelli F, Barba M, Federico R, Signore F, Gucciardo G, Grillo R, Woster PM, Casero RA, Jr, Mariottini P. Spermine oxidase (SMO) activity in breast tumor tissues and biochemical analysis of the anticancer spermine analogues BENSpm and CPENSpm. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:555. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu HS, Thompson TA, Church DR, Clower CC, Mehraein-Ghomi F, Amlong CA, Martin CT, Woster PM, Lindstrom MJ, Wilding G. A small molecule polyamine oxidase inhibitor blocks androgen-induced oxidative stress and delays prostate cancer progression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7689–7695. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zahedi K, Huttinger F, Morrison R, Murray-Stewart T, Casero RA, Strauss KI. Polyamine catabolism is enhanced after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:515–525. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takano K, Ogura M, Nakamura Y, Yoneda Y. Neuronal and glial responses to polyamines in the ischemic brain. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2005;2:213–223. doi: 10.2174/1567202054368335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seiler N. Oxidation of polyamines and brain injury. Neurochem. Res. 2000;25:471–490. doi: 10.1023/a:1007508008731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casero RA, Pegg AE. Polyamine catabolism and disease. Biochem. J. 2009;421:323–338. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomitori H, Usui T, Saeki N, Ueda S, Kase H, Nishimura K, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. Polyamine oxidase and acrolein as novel biochemical markers for diagnosis of cerebral stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2609–2613. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190004.36793.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida M, Tomitori H, Machi Y, Katagiri D, Ueda S, Horiguchi K, Kobayashi E, Saeki N, Nishimura K, Ishii I, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. Acrolein, IL-6 and CRP as markers of silent brain infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narayanan SP, Xu Z, Putluri N, Sreekumar A, Lemtalsi T, Caldwell RW, Caldwell RB. Arginase 2 deficiency reduces hyperoxia-mediated retinal neurodegeneration through the regulation of polyamine metabolism. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1075. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnett JM, Yanni SE, Penn JS. The development of the rat model of retinopathy of prematurity. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2010;120:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10633-009-9180-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cervelli M, Bellavia G, D'Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Moreno S, Berger J, Nardacci R, Marcoli M, Maura G, Piacentini M, Amendola R, Cecconi F, Mariottini P. A new transgenic mouse model for studying the neurotoxicity of spermine oxidase dosage in the response to excitotoxic injury. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dogan A, Rao AM, Hatcher J, Rao VL, Baskaya MK, Dempsey RJ. Effects of MDL 72527, a specific inhibitor of polyamine oxidase, on brain edema, ischemic injury volume, and tissue polyamine levels in rats after temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:765–770. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lobov IB, Renard RA, Papadopoulos N, Gale NW, Thurston G, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ. Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) is induced by VEGF as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:3219–3224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611206104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roque RS, Caldwell RB. Isolation and culture of retinal microglia. Curr. Eye Res. 1993;12:285–290. doi: 10.3109/02713689308999475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang JY, Lee CT, Wang JY. Nitric oxide plays a dual role in the oxidative injury of cultured rat microglia but not astroglia. Neuroscience. 2014;281C:164–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Chu CH, Stewart T, Ginghina C, Wang Y, Nie H, Guo M, Wilson B, Hong JS. Zhang J: alpha-Synuclein, a chemoattractant, directs microglial migration via H2O2-dependent Lyn phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:E1926–E1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417883112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kauppinen RA, Alhonen LI. Transgenic animals as models in the study of the neurobiological role of polyamines. Prog. Neurobiol. 1995;47:545–563. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paschen W. Polyamine metabolism in reversible cerebral ischemia. Cerebrovasc. Brain Metab. Rev. 1992;4:59–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seiler N, Duranton B, Raul F. The polyamine oxidase inactivator MDL 72527. Prog. Drug Res. 2002;59:1–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8171-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodwin AC, Destefano Shields CE, Wu S, Huso DL, Wu X, Murray-Stewart TR, Hacker-Prietz A, Rabizadeh S, Woster PM, Sears CL, Casero RA., Jr Polyamine catabolism contributes to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced colon tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:15354–15359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010203108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaturvedi R, de Sablet T, Asim M, Piazuelo MB, Barry DP, Verriere TG, Sierra JC, Hardbower DM, Delgado AG, Schneider BG, Israel DA, Romero-Gallo J, Nagy TA, Morgan DR, Murray-Stewart T, Bravo LE, Peek RM, Jr, Fox JG, Woster PM, Casero RA, Jr, Correa P, Wilson KT. Increased Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric cancer risk in the Andean region of Colombia is mediated by spermine oxidase. Oncogene. 2015;34:3429–3440. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Zhang SX, Hartnett ME. Signaling pathways triggered by oxidative stress that mediate features of severe retinopathy of prematurity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:80–85. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartnett ME. Studies on the pathogenesis of avascular retina and neovascularization into the vitreous in peripheral severe retinopathy of prematurity (an american ophthalmological society thesis) Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2010;108:96–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edgar KS, Matesanz N, Gardiner TA, Katusic ZS, McDonald DM. Hyperoxia depletes (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin levels in the neonatal retina: implications for nitric oxide synthase function in retinopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 2015;185:1769–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lange C, Ehlken C, Stahl A, Martin G, Hansen L, Agostini HT. Kinetics of retinal vaso-obliteration and neovascularisation in the oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1205–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierce EA, Foley ED, Smith LE. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by oxygen in a model of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1219–1228. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140419009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stone J, Itin A, Alon T, Pe'er J, Gnessin H, Chan-Ling T, Keshet E. Development of retinal vasculature is mediated by hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression by neuroglia. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4738–4747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04738.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang M, Wang X, Zhao L, Ma W, Rodriguez IR, Fariss RN, Wong WT. Macroglia-microglia interactions via TSPO signaling regulates microglial activation in the mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:3793–3806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3153-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng HY, Green WR, Tso MO. Microglial activation in human diabetic retinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008;126:227–232. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krady JK, Basu A, Allen CM, Xu Y, LaNoue KF, Gardner TW, Levison SW. Minocycline reduces proinflammatory cytokine expression, microglial activation, and caspase-3 activation in a rodent model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2005;54:1559–1565. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tremblay S, Miloudi K, Chaychi S, Favret S, Binet F, Polosa A, Lachapelle P, Chemtob S, Sapieha P. Systemic inflammation perturbs developmental retinal angiogenesis and neuroretinal function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:8125–8139. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kowluru RA, Odenbach S. Role of interleukin-1beta in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1343–1347. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.038133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnsen-Soriano S, Sancho-Tello M, Arnal E, Navea A, Cervera E, Bosch-Morell F, Miranda M, Javier Romero F. IL-2 and IFN-gamma in the retina of diabetic rats. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010;248:985–990. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Demircan N, Safran BG, Soylu M, Ozcan AA, Sizmaz S. Determination of vitreous interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) levels in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eye (Lond.) 2006;20:1366–1369. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mocan MC, Kadayifcilar S, Eldem B. Elevated intravitreal interleukin-6 levels in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2006;41:747–752. doi: 10.3129/i06-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu Z, Gong C, Lu B, Yang L, Sheng Y, Ji L, Wang Z. Dendrobium chrysotoxum Lindl. Alleviates diabetic retinopathy by preventing retinal inflammation and tight junction protein decrease. J. Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:518317. doi: 10.1155/2015/518317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morini M, Albini A, Lorusso G, Moelling K, Lu B, Cilli M, Ferrini S, Noonan DM. Prevention of angiogenesis by naked DNA IL-12 gene transfer: angioprevention by immunogene therapy. Gene Ther. 2004;11:284–291. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5771–5777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qin L, Liu Y, Hong JS, Crews FT. NADPH oxidase and aging drive microglial activation, oxidative stress, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration following systemic LPS administration. Glia. 2013;61:855–868. doi: 10.1002/glia.22479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Neerven S, Regen T, Wolf D, Nemes A, Johann S, Beyer C, Hanisch UK, Mey J. Inflammatory chemokine release of astrocytes in vitro is reduced by all-trans retinoic acid. J. Neurochem. 2010;114:1511–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meeuwsen S, Persoon-Deen C, Bsibsi M, Ravid R, van Noort JM. Cytokine, chemokine and growth factor gene profiling of cultured human astrocytes after exposure to proinflammatory stimuli. Glia. 2003;43:243–253. doi: 10.1002/glia.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quinones MP, Kalkonde Y, Estrada CA, Jimenez F, Ramirez R, Mahimainathan L, Mummidi S, Choudhury GG, Martinez H, Adams L, Mack M, Reddick RL, Maffi S, Haralambous S, Probert L, Ahuja SK, Ahuja SS. Role of astrocytes and chemokine systems in acute TNFalpha induced demyelinating syndrome: CCR2-dependent signals promote astrocyte activation and survival via NF-kappaB and Akt. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2008;37:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, Gomez A, Ros CM, Ros-Bernal F, Martin ED, Perez-Valles A, Gallego-Sanchez JM, Fernandez-Villalba E, Barcia C, Sr, Barcia C, Jr, Herrero MT. CCL2-expressing astrocytes mediate the extravasation of T lymphocytes in the brain. Evidence from patients with glioma and experimental models in vivo. PloS One. 2012;7:e30762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]