Abstract

We report a case of a choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) associated with sclerochoroidal calcification (SCC). An asymptomatic, 72-year-old male was referred to our institution for yellow-white placoid retinal lesions of both eyes. B-scan ultrasonography confirmed the diagnosis of SCC, and indocyanine green angiography confirmed the presence of an associated CNVM. Due to enlargement of a hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachment associated with the CNVM over the course of 7 months, the patient was treated with a series of bevacizumab injections followed by photodynamic therapy (PDT). Due to persistence of the CNVM following PDT, the lesion was finally treated with argon laser photocoagulation. We describe the clinical course of this rare complication of SCC.

Key Words: Sclerochoroidal calcification, Choroidal neovascular membrane, Bevacizumab, Photodynamic therapy, Argon laser photocoagulation

Introduction

Sclerochoroidal calcification (SCC) is a benign ocular condition often noted incidentally on examination of elderly individuals [1]. Clinically, it is characterized by yellow or yellow-white lesions in the postequatorial fundus, most often in the superotemporal quadrant, which commonly appear flat but can also be elevated, mimicking a choroidal tumor. The lesions may be single or multiple and are often bilateral [2,3]. B-scan ultrasonography demonstrating acoustic shadowing characteristic of calcification can help confirm the diagnosis. Enhanced-depth optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows the lesions arising from the sclera with thinning or absence of the overlying choroid [4]. In the vast majority of cases, SCC is idiopathic but may be associated with secondary causes of hypercalcemia. Despite the benign nature of SCC, it can lead to atrophy of the overlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and, rarely, secondary choroidal neovascularization, which can be vision-threatening [2]. Herein, we describe a case of choroidal neovascularization associated with SCC.

Case Report

A 72-year-old male was referred to the ocular oncology service for evaluation of suspicious choroidal lesions in both eyes found incidentally on routine eye examination. Best-corrected visual acuity in both eyes was 20/20. Intraocular pressure was within normal limits, and anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Fundus examination of the right eye revealed several ill-defined, yellow-white choroidal lesions with areas of discrete calcification and overlying RPE atrophy in the superotemporal and inferotemporal quadrants. Two similar lesions were present along the temporal arcades in the left eye. The superotemporal lesions in the right eye were associated with a hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachment (PED) along the temporal border (fig. 1). B-scan ultrasonography of the right eye revealed multiple areas of plaque-like, dense calcification of the sclera causing shadowing of the orbit consistent with SCC (fig. 2a). OCT through the superotemporal areas of calcification showed an irregular elevation of the choroid and retina with thinning of the choroid most prominent at the lateral edges of the lesion (fig. 2b). OCT also confirmed the presence of a hemorrhagic PED with surrounding intraretinal fluid (fig. 2c). Fluorescein angiography (FA) revealed blockage due to the subretinal hemorrhage and late staining of the SCC without obvious leakage from a choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM; fig. 2d-e). Although the fluorescein angiogram was unrevealing, the clinical appearance was highly suggestive of choroidal neovascularization associated with SCC. Given the hemorrhage was outside of the macula and no CNVM was identified, observation was recommended. A work-up for systemic hypercalcemia was undertaken and did not reveal any abnormality.

Fig. 1.

Optos fundus photo of the right eye showing SCC along the superotemporal and inferotemporal arcades with a hemorrhagic PED temporal to the superior lesions.

Fig. 2.

a B-scan ultrasonography demonstrating acoustic shadowing of SCC. b Cirrus OCT through the superotemporal calcified lesions. c Cirrus OCT through the hemorrhagic PED demonstrating intraretinal fluid on the superior and inferior aspects of the lesion. d Fluorescein angiogram in the transit phase showing blockage from the PED. e Late-phase angiogram demonstrating staining of the SCC without leakage.

The patient was referred back 7 months later due to concern for enlargement of the choroidal lesions. Vision was unchanged. Fundus examination revealed an increase in size of the known hemorrhagic PED, which had now become dehemoglobinized (fig. 3a). Indocyanine green angiography (ICG) confirmed the presence of a CNVM along the posterior margin of the PED (fig. 3b, c). Given the enlargement of the PED, active leakage on ICG, and potential for extension of the PED into the macula, treatment was recommended. The patient received a total of 3 bevacizumab injections (1.25 mg/0.05 ml) over the course of 6 months.

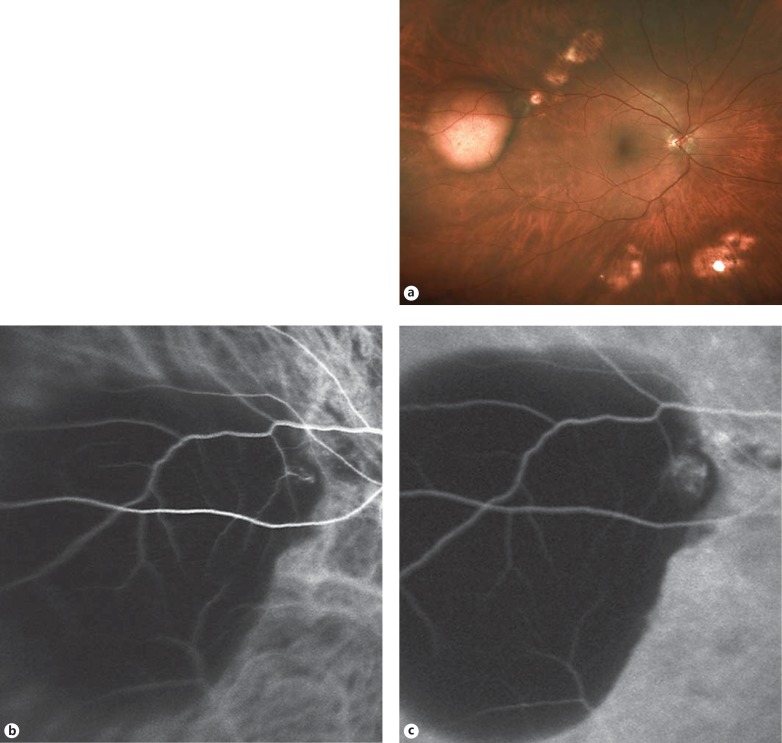

Fig. 3.

a Optos photo of the right eye showing enlargement of the PED. b, c. Early- and late-frame ICG showing leakage from the CNVM.

On his 6-month follow-up examination, there was significant improvement in the size of the hemorrhagic PED; however, FA revealed a persistent CNVM. Given the persistent CNVM and the anticipated treatment burden of multiple intravitreal injections, photodynamic therapy was performed. On follow-up 3 months later, a new subretinal hemorrhage was noted, and FA confirmed the presence of an active CNVM (fig. 4). Given the incomplete response to photodynamic therapy (PDT), argon laser photocoagulation was performed. At 1 month of follow-up, the subretinal hemorrhage had resolved, and there was no evidence of active leakage on FA or OCT.

Fig. 4.

a Late-phase FA showing leakage along the superotemporal arcade (solid arrow) with blockage along the temporal aspect, corresponding to new subretinal hemorrhage (hollow arrow). b Cirrus OCT showing an area of subretinal hyperreflectivity (solid arrow) overlying an irregular elevation of the RPE adjacent to the SCC, which corresponds to the leakage on FA. The area of subretinal hyperreflectivity on the temporal aspect corresponds to the subretinal hemorrhage (hollow arrow).

Discussion

Choroidal neovascularization is a rare complication of SCC. To date, there have been 3 case reports in the English literature. Cohen et al. [5] described a CNVM in a patient with SCC associated with a history of hyperparathyroidism successfully treated with argon laser photocoagulation. Leys et al. [6] reported a second case in a patient with secondary hyperparathyroidism. The lesion was treated with argon laser photocoagulation, and there was no recurrence over the 7-year follow-up period. In their case series of 38 eyes with SCC, Honavar et al. [1] found only 1 case of CNVM, which did not affect central visual acuity and remained stable without treatment through 1 year of follow-up.

Given the tendency of SCC lesions to remain outside the macula and thus the low probability of vision loss from an associated CNVM, observation may be the best initial course of action. However, our case demonstrates that these patients need to be followed closely as exudative lesions can continue to enlarge over time and may eventually involve the macular area with potential for vision loss.

Should treatment be warranted, careful consideration should be given to the location of the CNVM. In our case, the CNVM responded well to bevacizumab injections; however, the need for continued injections in a patient whose central vision was uninvolved proved burdensome. Argon laser photocoagulation was more effective than PDT in our experience and may be a good option in a patient with an extramacular CNVM.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol has been approved by the Institute's Committee on Human Research. The study application was approved as Exempt Research by the Institutional Review Board for the collection of data in an anonymous manner in which participants were not identifiable.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Honavar SG, Shields CL, Demirci H, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcification. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:833–840. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields CL, Hasanreisoglu M, Saktanasate J, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcification: clinical features, outcomes, and relationship with hypercalcemia and parathyroid adenoma in 179 eyes. Retina. 2015;35:547–554. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horgan N, Singh AD. Uveal osseous tumors. In: Damato BE, Singh AD, editors. Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Uveal Tumors. Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. pp. 365–376. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasanreisoglu M, Saktanasate J, Shields PW, et al. Classification of calcification based on enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography ‘mountain-like’ features. Retina. 2015;35:1407–1414. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen SY, Guyot-Sionnest M, Puech M. Choroidal neovascularization as a late complication of hyperparathyroidism. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:320–322. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leys A, Stalmans P, Blanckaert J, et al. Sclerochoroidal calcification with choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:854–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]