The RAISE phase III trial demonstrated ramucirumab + FOLFIRI improved survival compared with placebo + FOLFIRI for second-line metastatic colorectal carcinoma patients previously treated with first-line bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine. Analyses reported here found similar efficacy and safety in patients regardless of KRAS mutational status, time to first-line progression, and age.

Keywords: ramucirumab, metastatic colorectal carcinoma, CRC, VEGFR-2, RAISE, phase III clinical trial

Abstract

Background

The RAISE phase III clinical trial demonstrated that ramucirumab + FOLFIRI improved overall survival (OS) [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.844, P = 0.0219] and progression-free survival (PFS) (HR = 0.793, P < 0.0005) compared with placebo + FOLFIRI for second-line metastatic colorectal carcinoma (mCRC) patients previously treated with first-line bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine. Since some patient or disease characteristics could be associated with differential efficacy or safety, prespecified subgroup analyses were undertaken. This report focuses on three of the most relevant ones: KRAS status (wild-type versus mutant), age (<65 versus ≥65 years), and time to progression (TTP) on first-line therapy (<6 versus ≥6 months).

Patients and methods

OS and PFS were evaluated by the Kaplan–Meier analysis, with HR determined by the Cox proportional hazards model. Treatment-by-subgroup interaction was tested to determine whether treatment effect was consistent between subgroup pairs.

Results

Patients with both wild-type and mutant KRAS benefited from ramucirumab + FOLFIRI treatment over placebo + FOLFIRI (interaction P = 0.526); although numerically, wild-type KRAS patients benefited more (wild-type KRAS: median OS = 14.4 versus 11.9 months, HR = 0.82, P = 0.049; mutant KRAS: median OS = 12.7 versus 11.3 months, HR = 0.89, P = 0.263). Patients with both longer and shorter first-line TTP benefited from ramucirumab (interaction P = 0.9434), although TTP <6 months was associated with poorer OS (TTP ≥6 months: median OS = 14.3 versus 12.5 months, HR = 0.86, P = 0.061; TTP <6 months: median OS = 10.4 versus 8.0 months, HR = 0.86, P = 0.276). The subgroups of patients ≥65 versus <65 years also derived a similar ramucirumab survival benefit (interaction P = 0.9521) (≥65 years: median OS = 13.8 versus 11.7 months, HR = 0.85, P = 0.156; <65 years: median OS = 13.1 versus 11.9 months, HR = 0.86, P = 0.098). The safety profile of ramucirumab + FOLFIRI was similar across subgroups.

Conclusions

These analyses revealed similar efficacy and safety among patient subgroups with differing KRAS mutation status, longer or shorter first-line TTP, and age. Ramucirumab is a beneficial addition to second-line FOLFIRI treatment for a wide range of patients with mCRC.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01183780

introduction

Metastatic colorectal carcinoma (mCRC) develops in approximately half of patients diagnosed with the disease [1]. The poor prognosis and 5-year survival rate (13.5%) of patients with mCRC drives ongoing efforts to find treatments that slow its progression [2].

Adding anti-angiogenic agents to chemotherapy to improve outcomes has become standard of care for treatment of mCRC [1, 3]. Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) is a key stimulator of capillary growth [4]. Evidence suggests that VEGF-A interaction with VEGF Receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) is an important mediator of vascular growth in tumors [5, 6]. Some anti-angiogenic agents, such as bevacizumab, bind to circulating VEGF molecules, eliminating their ability to bind to VEGF receptors, thus blocking their mitogenic effects. Preventing growth factor–receptor interaction by blocking the binding site on the VEGF-R is a different strategy to disrupt the VEGF angiogenic pathway.

Ramucirumab (IMC-1121B, Eli Lilly and Company) is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to the VEGFR-2 extracellular domain with high affinity (Kd 50 pM), preventing binding of all VEGF ligands and ensuing receptor activation [7]. The RAISE trial showed that second-line ramucirumab in combination with irinotecan, folinic acid, and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFIRI) improved survival in patients with mCRC following progression during or after first-line combination therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine [8]. Overall survival (OS) for the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm was 13.3 months compared with 11.7 months in the placebo + FOLFIRI arm [hazard ratio, HR = 0.844, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.730–0.976, P = 0.0219]. Likewise, progression-free survival (PFS) was extended in the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm over the placebo + FOLFIRI arm (HR 0.793, 95% CI 0.697–0.903, P < 0.0005) [8].

A consistent OS and PFS benefit for ramucirumab + FOLFIRI was observed across prespecified subgroups in the RAISE trial. The subgroups had been chosen to reflect stratification factors, regulatory requirements, and known prognostic and disease factors. Some tumor or patient characteristics are known to be associated with differential efficacy or safety among subgroups of patients with mCRC. For example, patients with activating KRAS mutations (exon 2) are resistant to anti-EGFR therapy, whereas patients with no activating KRAS mutations may benefit from that type of treatment [9]. Advanced age has been associated with more pronounced or frequent safety concerns; as a result, the risk–benefit balance of cancer treatments in the elderly population has been under scrutiny [10]. In some cases, patients with more and less aggressive disease, as assessed by time to progression (TTP) on first-line therapy, could have differential responsiveness to second-line therapy [11].

Given the importance of identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from ramucirumab treatment of mCRC, the prespecified data analyses presented here further examine these three key subgroup pairings: KRAS mutation status (mutant, wild type), age (<65 years and ≥65 years old), and TTP after start on first-line therapy (<6 and ≥6 months). The objective was to determine whether any of these three characteristics was associated with a differential outcome to ramucirumab's anti-VEGF pathway effects.

methods

study design

The study design and conduct of the global, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III RAISE trial was previously reported [8] and is summarized in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

statistical analyses

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the median PFS and OS of each arm in RAISE patient KRAS, age, and TTP subgroups. For each subgroup, HRs and 95% CIs were calculated by unstratified Cox proportional hazards model, and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival distributions between the two arms. To determine whether the treatment effect was consistent between subgroup pairs, a treatment-by-subgroup interaction P-value was calculated based on Wald test in unstratified Cox proportional hazards model. A multivariate Cox regression analysis of OS time was used to assess the treatment effect after adjusting important prognostic factors.

Safety analyses included all patients who received at least one dose of any study drug. Subgroup analyses of safety data were carried out for treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), overall, and by maximum CTCAE grade. Statistical tests and CIs used a two-sided 0.05 α-level, whereas tests of interactions used two-sided 0.10. SAS (version 9.1.2 or higher) software was used for all statistical analyses.

results

The RAISE phase III clinical trial enrolled 1072 patients, with 536 patients in each arm: ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm and placebo + FOLFIRI (intent-to-treat, ITT population). Among these patients, 529 in the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm and 528 in the placebo + FOLFIRI arm received ≥1 dose of treatment and comprised the safety population. At the time of primary analysis, there were 769 patient deaths, with a censoring rate of 31.6% for ramucirumab + FOLFIRI and 25.9% for placebo + FOLFIRI. In the trial population, baseline demographic, disease, and pre-treatment characteristics were balanced across treatment arms [8]. Among all study patients, 83% had ≥3 months of first-line bevacizumab.

Approximately half of the patients had KRAS exon 2 mutant (n = 542) and wild-type (n = 530) tumors, respectively. Within each KRAS subgroup, baseline patient and tumor characteristics were balanced between treatment groups (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Patients were also divided into subgroups of those with more or less aggressive disease, as defined by those progressing on first-line therapy in <6 months (n = 254) versus ≥6 months (n = 818), respectively. Within these TTP subgroups, baseline patient and tumor characteristics were balanced between treatment groups (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Likewise, age subgroups, <65 years (n = 645) and ≥65 years (n = 427), exhibited a balanced distribution of patient and tumor characteristics between treatment arms (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

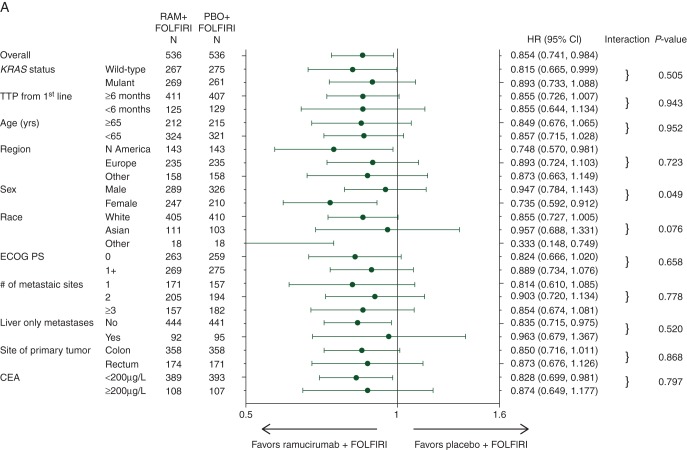

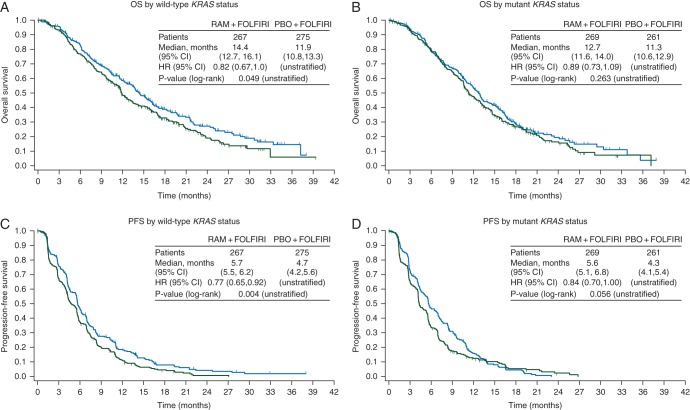

Although the study was not powered for subgroup analysis, there was a consistent positive ramucirumab treatment effect in all subgroups analyzed, including those defined by KRAS mutation status (Figure 1). Second-line treatment with ramucirumab + FOLFIRI significantly improved OS in patients with wild-type KRAS (HR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.00, P = 0.049) (Figure 2A). The median OS for that patient population was 14.4 months for the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm versus 11.9 months for the placebo + FOLFIRI arm. PFS was also significantly improved (HR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.65–0.92, P = 0.004) (Figure 2C). Patients with mutant KRAS exhibited a directional improvement in OS (HR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.73–1.09, P = 0.263); the median OS was 12.7 months for the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm versus 11.3 months for the placebo + FOLFIRI arm. PFS also displayed directional improvement (HR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.70–1.00, P = 0.056) (Figure 2B and D). For both efficacy end points, there was no significant interaction between treatment and KRAS subgroups (interaction P = 0.505 for OS and 0.526 for PFS) (Figure 1), suggesting that ramucirumab can benefit patients regardless of KRAS mutation status. Efficacy data for this subgroup and others are summarized (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Forest plots for (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival in subgroups. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown for subgroups as defined by baseline patient and tumor characteristics. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; RAM, ramucirumab; PBO, placebo; TTP, time to progression.

Figure 2.

Graphs of the Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A and B) overall survival and (C and D) progression-free survival by wild-type (A and C) and mutant (B and D) KRAS status. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; RAM, ramucirumab; PBO, placebo; n, number of patients; OS, overall survival (months); PFS, progression-free survival (months).

To determine whether anti-EGFR post-discontinuation therapy influenced the magnitude of OS and PFS for the wild-type KRAS patients, we reviewed post-discontinuation therapy data. All post-discontinuation treatments were well balanced between arms. Anti-EGFR therapy was administered to 27.1% of all patients after progression on ramucirumab + FOLFIRI or placebo + FOLFIRI. Almost all of these patients were KRAS wild-type (95.5%). Examining just the wild-type KRAS population, patients receiving post-discontinuation anti-EGFR therapy were evenly distributed between arms [ramucirumab: 132 patients (49.4%) and placebo: 145 patients (52.7%)]. Thus, the improvement in OS and PFS in the KRAS wild-type patients is unlikely to be related to post-discontinuation anti-EGFR therapy since that variable was well balanced between arms.

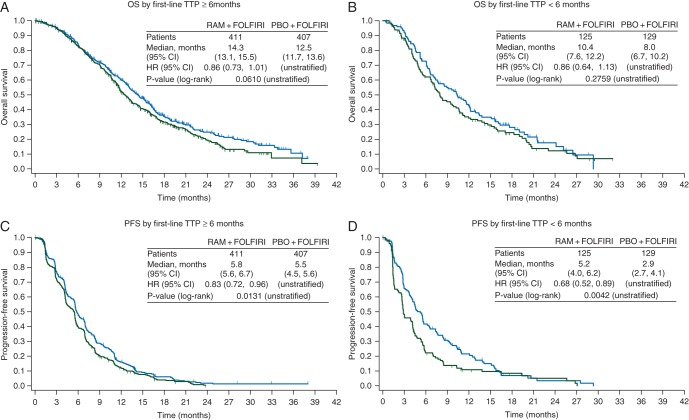

Patient subgroups based on first-line TTP also exhibited a treatment effect in favor of the ramucirumab arm for both efficacy end points. Patients who had progressed in ≥6 months showed directional survival improvement (HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.73–1.01, P = 0.061), with a median OS of 14.3 months for the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI arm versus 12.5 months for the placebo + FOLFIRI arm, and significant improvement in PFS (HR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.72–0.96, P = 0.013) (Figure 3A and C). Treatment with ramucirumab also led to better efficacy outcomes among the 24% (254/1078) of patients who progressed on first-line therapy in <6 months: median OS = 10.4 versus 8.0 months, HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.64–1.13, P = 0.2759; PFS HR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.52–0.89, P = 0.0042 (Figure 3B and D). There was no interaction between first-line TTP status and treatment effect for either efficacy end point (OS interaction P = 0.9434; PFS interaction P = 0.1142) (Figure 1), showing that ramucirumab benefits patients who progress both more and less rapidly on first-line therapy. However, first-line TTP (<6 versus ≥6 months) was found to be a prognostic factor for second-line mCRC patients: HR = 1.55 (95% CI 1.31–1.84, Wald's P < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Graphs of the Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A and B) overall survival and (C and D) progression-free survival by time to progression on first-line therapy ≥6 months (A and C) and <6 months (B and D). CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; RAM, ramucirumab; PBO, placebo; n, number of patients; OS, overall survival (months); PFS, progression-free survival (months); TTP, time to progression.

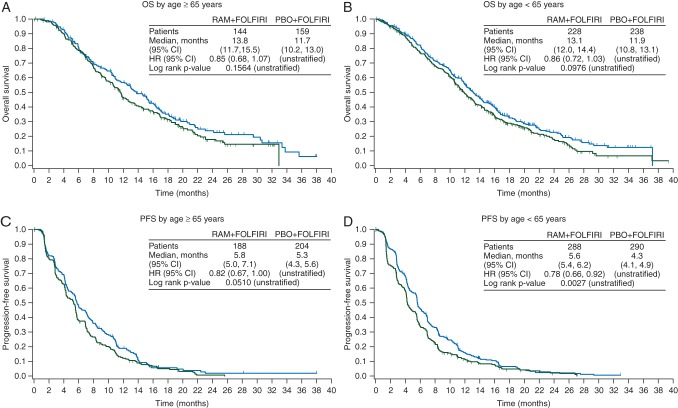

Both age subgroups also benefited from treatment with ramucirumab. In the ≥65 years subgroup, there was directional improvement in both OS (HR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.68–1.07, P = 0.156) and PFS (HR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.00, P = 0.051) (Figure 4A and C), with a median OS of 13.8 versus 11.7 months. The <65 years subgroup displayed similar improvement in OS (HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.72–1.03, P = 0.098), with a median OS of 13.1 versus 11.9 months (Figure 4B). PFS was significantly improved in the ramucirumab-treated arm (HR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.66–0.92, P = 0.0027) (Figure 4D). The treatment effect was not statistically different between patients younger and older than 65 years, demonstrated by the lack of treatment-by-subgroup interaction (Figure 1), thus ramucirumab can positively affect efficacy for both older and younger patients.

Figure 4.

Graphs of the Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A and B) overall survival and (C and D) progression-free survival by age ≥65 (A and C) and <65 (B and D) years. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; RAM, ramucirumab; PBO, placebo; n, number of patients; OS, overall survival (months); PFS, progression-free survival (months).

The incidence of ‘all grade’ and grade ≥3 TEAEs in the subgroups was relatively consistent across patient KRAS mutation and first-line TTP subgroups (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). TEAEs that occurred more frequently among patients treated with ramucirumab + FOLFIRI (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, stomatitis, epistaxis, hypertension) were elevated to a similar extent in both paired subgroups. Special interest TEAEs (those associated with anti-VEGF therapies) showed an equivalent incidence across KRAS and first-line TTP subgroups (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Because age can be associated with a higher incidence of TEAEs for some treatments, we also examined subgroups with 65 and 75 years as the cut-off (Table 1). For many TEAEs, older patients had a similar incidence as younger patients. For those TEAEs that occur more frequently with age (e.g. decreased appetite and fatigue), the increased incidence was of similar magnitude in both the ramucirumab + FOLFIRI and placebo + FOLFIRI arms. Examination of the TEAEs associated with anti-VEGF therapies found they were not elevated in either the ≥65 or ≥75 subgroup of patients (supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 1.

RAISE treatment-emergent adverse events in age subgroupsa

| Preferred term | Any grade |

Grade ≥3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAM + FOLFIRI |

PBO + FOLFIRI |

RAM + FOLFIRI |

PBO + FOLFIRI |

|||||

| Age ≥65 n = 209 n (%) |

Age <65 n = 320 n (%) |

Age ≥65 n = 212 n (%) |

Age <65 n = 316 n (%) |

Age ≥65 n = 209 n (%) |

Age <65 n = 320 n (%) |

Age ≥65 n = 212 n (%) |

Age <65 n = 316 n (%) |

|

| Neutropenia | 124 (59.3) | 187 (58.4) | 108 (50.9) | 133 (42.1) | 81 (38.8) | 122 (38.1) | 59 (27.8) | 64 (20.3) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 72 (34.4) | 78 (24.4) | 31 (14.6) | 41 (13.0) | 8 (3.8) | 8 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) |

| Anemia | 34 (16.3) | 52 (16.3) | 49 (23.1) | 61 (19.3) | 2 (1.0) | 6 (1.9) | 7 (3.3) | 12 (3.8) |

| Diarrhea | 139 (66.5) | 177 (55.3) | 114 (53.8) | 157 (49.7) | 29 (13.9) | 28 (8.8) | 22 (10.4) | 29 (9.2) |

| Fatigue | 133 (63.6) | 172 (53.8) | 114 (53.8) | 161 (50.9) | 32 (15.3) | 29 (9.1) | 23 (10.8) | 18 (5.7) |

| Nausea | 95 (45.5) | 167 (52.2) | 96 (45.3) | 175 (55.4) | 4 (1.9) | 9 (2.8) | 3 (1.4) | 11 (3.5) |

| Decreased appetite | 92 (44.0) | 106 (33.1) | 66 (31.1) | 78 (24.7) | 9 (4.3) | 4 (1.3) | 5 (2.4) | 5 (1.6) |

| Stomatitis | 64 (30.6) | 99 (30.9) | 52 (24.5) | 58 (18.4) | 11 (5.3) | 9 (2.8) | 5 (2.4) | 7 (2.2) |

| Epistaxis | 77 (36.8) | 100 (31.3) | 37 (17.5) | 42 (13.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 50 (23.9) | 104 (32.5) | 52 (24.5) | 92 (29.1) | 4 (1.9) | 11 (3.4) | 4 (1.9) | 9 (2.8) |

| Alopecia | 66 (31.6) | 89 (27.8) | 72 (34.0) | 93 (29.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Abdominal pain | 48 (23.0) | 92 (28.8) | 52 (24.5) | 87 (27.5) | 5 (2.4) | 13 (4.1) | 9 (4.2) | 10 (3.2) |

| Constipation | 60 (28.7) | 91 (28.4) | 51 (24.1) | 69 (21.8) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (1.4) | 5 (1.6) |

| Hypertension | 47 (22.5) | 89 (27.8) | 17 (8.0) | 28 (8.9) | 22 (10.5) | 35 (10.9) | 5 (2.4) | 10 (3.2) |

| Peripheral edema | 60 (28.7) | 48 (15.0) | 26 (12.3) | 22 (7.0) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Age ≥75 n = 51 n (%) |

Age <75 n = 478 n (%) |

Age ≥75 n = 41 n (%) |

Age <75 n = 487 n (%) |

Age ≥75 n = 51 n (%) |

Age <75 n = 478 n (%) |

Age ≥75 n = 41 n (%) |

Age <75 n = 487 n (%) |

|

| Neutropenia | 27 (52.9) | 284 (59.4) | 20 (48.8) | 221 (45.4) | 20 (39.2) | 183 (38.3) | 14 (34.1) | 109 (22.4) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 11 (21.6) | 139 (29.1) | 6 (14.6) | 66 (13.6) | 0 | 16 (3.3) | 0 | 4 (0.8) |

| Anemia | 10 (19.6) | 76 (15.9) | 13 (31.7) | 97 (19.9) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (1.5) | 1 (2.4) | 18 (3.7) |

| Diarrhea | 34 (66.7) | 282 (59.0) | 19 (46.3) | 252 (51.7) | 7 (13.7) | 50 (10.5) | 4 (9.8) | 47 (9.7) |

| Fatigue | 39 (76.5) | 266 (55.6) | 23 (56.1) | 252 (51.7) | 14 (27.5) | 47 (9.8) | 6 (14.6) | 35 (7.2) |

| Nausea | 18 (35.3) | 244 (51.0) | 16 (39.0) | 255 (52.4) | 0 | 13 (2.7) | 0 | 14 (2.9) |

| Decreased appetite | 26 (51.0) | 172 (36.0) | 16 (39.0) | 128 (26.3) | 2 (3.9) | 11 (2.3) | 3 (7.3) | 7 (1.4) |

| Stomatitis | 16 (31.4) | 147 (30.8) | 10 (24.4) | 100 (20.5) | 3 (5.9) | 17 (3.6) | 2 (4.9) | 10 (2.1) |

| Epistaxis | 17 (33.3) | 160 (33.5) | 6 (14.6) | 73 (15.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 9 (17.6) | 145 (30.3) | 10 (24.4) | 134 (27.5) | 1 (2.0) | 14 (2.9) | 0 | 13 (2.7) |

| Alopecia | 18 (35.3) | 137 (28.7) | 12 (29.3) | 153 (31.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 11 (21.6) | 129 (27.0) | 7 (17.1) | 132 (27.1) | 0 | 18 (3.8) | 1 (2.4) | 18 (3.7) |

| Constipation | 16 (31.4) | 135 (28.2) | 10 (24.4) | 110 (22.6) | 0 | 5 (1.0) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (1.4) |

| Hypertension | 7 (13.7) | 129 (27.0) | 2 (4.9) | 43 (8.8) | 3 (5.9) | 54 (11.3) | 0 | 15 (3.1) |

| Peripheral edema | 18 (35.3) | 90 (18.8) | 6 (14.6) | 42 (8.6) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

n, safety population; NA, not applicable; PBO, placebo; RAM, ramucirumab; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

aTEAEs that occur in ≥20% of patients at any grade in either treatment arm, and grade ≥3 TEAEs that occur in ≥5% of patients in either treatment arm. TEAE graded by NCI-CTCAE v4.0. Terms in italics are consolidated terms, that is, a composite term consisting of multiple related preferred terms based on Standardized MedDRA Queries (SMQ) and medical review.

As previously reported [8], ramucirumab dose adjustments (reductions, omissions, delays) and discontinuations showed some greater incidence in the ramucirumab treatment arm; however, there was no difference in incidence within KRAS, TTP, or age subgroups (data not shown).

discussion

The inherent heterogeneity of mCRC complicates identifying patients more likely to benefit from treatment. Predicting patients more likely to benefit from the addition of ramucirumab to FOLFIRI second-line therapy would be useful to balance its potential benefit with possible increased toxicities, in addition to quality-of-life and economic considerations. This report focused on the KRAS, first-line TTP, and age subgroups in the RAISE population since they are important as prognostic or predictive factors and may affect safety.

KRAS status had been shown to impact anti-EGFR treatment [9], thus prompting the question whether it also affected the efficacy of anti-angiogenic treatments. Our examination of the VEGFR2 antibody ramucirumab showed that patients with both mutant and wild-type KRAS derived benefit from ramucirumab + FOLFIRI treatment (interaction P = 0.526), although numerically, wild-type KRAS patients benefited more (mutant KRAS: median OS = 12.7 versus 11.3 months, HR = 0.89, P = 0.263; wild-type KRAS: median OS = 14.4 versus 11.9 months, HR = 0.82, P = 0.049). Likewise, KRAS status did not change the effect of second-line bevacizumab on OS in the TML trial (interaction P = 0.1266) [12]. However, patients with KRAS mutations in the TML trial did seem to derive less benefit from the bevacizumab–chemotherapy combination versus chemotherapy alone (median OS = 10.4 versus 10.0 months, HR = 0.92, P = 0.4969) than patients with wild-type KRAS (median OS = 15.4 versus 11.1 months, HR = 0.69, P = 0.0052) [12]. As in the RAISE study, this result may have been impacted by the study not having been powered to detect differences in subgroups. Whether KRAS status impacts the treatment effect of second-line aflibercept + FOLFIRI on the OS of the VELOUR mCRC patients has not been reported to date.

Other gene mutations have also been identified as impacting treatment of advanced CRC. BRAF mutation and extended RAS mutations other than KRAS exon 2 have also been found to reduce benefit from anti-EGFR therapies [13]. Post hoc analyses are being undertaken to characterize extended RAS and BRAF mutations in RAISE patient tumor samples to verify that these other mutations do not interfere with ramucirumab benefit.

Before this study, there was some indication that TTP <6 months after beginning first-line treatment may be a negative prognostic factor among patients undergoing irinotecan-based second-line therapy [11]. The RAISE study stratified patients by first-line TTP <6 versus ≥6 months and then examined the data following the study to determine whether TTP on first-line therapy was prognostic for OS. The median OS of patients who progressed on first-line therapy in <6 months was 10.4 months for ramucirumab + FOLFIRI versus 8.0 months for placebo + FOLFIRI. Patients who progressed on first-line therapy in ≥6 months exhibited a median OS of 14.3 versus 12.5 months, respectively. TTP <6 months on first-line therapy is prognostic for poorer median OS (in this study, ∼4 months), but both patients with longer and shorter first-line TTP received benefit from the addition of ramucirumab to standard FOLFIRI treatment. This result differentiates the RAISE study from the TML registration trial for second-line bevacizumab that excluded patients who progressed in <3 months on first-line bevacizumab with chemotherapy [14]. (The TML study also excluded patients who received <3 months of continued bevacizumab treatment in the first-line, whereas the RAISE study included both groups.) Since ramucirumab efficacy is similar in patients with both longer and shorter time to first-line progression and with either mutant or wild-type KRAS status, oncologists might consider it a beneficial addition to second-line chemotherapy.

Pooled analyses have shown that the efficacy of combination chemotherapy in healthy older mCRC patients is similar to that in younger patients [15–17]. However the declining physiologic reserves and organ function associated with aging reduces the ability of older patients to compensate for stressors such as chemotherapy and infection, thus increasing the incidence and severity of TEAE in older patients for some chemotherapies [18]. Our analyses of the ≥65 versus <65 years RAISE patient subgroups confirmed an equivalent ramucirumab + FOLFIRI treatment benefit (interaction P = 0.9521 for OS and 0.6965 for PFS). We also compared the incidence of all grade TEAEs and grade 3/4 TEAEs within the <65 and ≥65 age groups and found that those TEAEs associated with ramucirumab treatment were elevated to a similar extent in both age subgroups. Although the addition of ramucirumab to chemotherapy has been found to cause a manageable increase in grade ≥3 neutropenia [38.4% versus 23.3%, with low (∼3%) and similar febrile neutropenia between arms] and grade ≥3 hypertension (11.2% versus 2.8%) [8], neither neutropenia nor hypertension was further elevated in elderly patients. The same results held true for subgroups defined by age 75; however, the small size of the ≥75 subgroup requires confirmation of this result.

Treatment-by-subgroup interaction test was utilized in these analyses. This test largely had low statistical power as the study was not powered for testing treatment-by-subgroup interaction. However, given the generally large P-values, the presence of real interactions was not supported by the data.

The RAISE trial showed that the addition of ramucirumab to FOLFIRI demonstrated a consistent and clinically meaningful survival benefit for patients with mCRC who progressed on or after first-line combination therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine. The detailed analyses presented here reveal no efficacy or safety difference in response among patients with differing KRAS mutation status, longer or shorter first-line TTP, and age. Ramucirumab + FOLFIRI is an effective second-line treatment for a wide range of patients with mCRC.

funding

This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company. No grant number is applicable.

disclosure

RO reports an advisory role for Eli Lilly and honoraria for other pharmaceutical companies. GB reports an advisory role with Eli Lilly, and honoraria and an advisory role with other pharmaceutical companies. KY reports honoraria from Eli Lilly and other pharmaceutical companies. TY reports a research grant outside the submitted work and honoraria from pharmaceutical companies. JT, TC, and PGA report an advisory role for Eli Lilly and other pharmaceutical companies. AC reports honoraria from pharmaceutical companies. TWK and EVC report research grants from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work and an advisory role for Eli Lilly. DP reports an advisory role with a pharmaceutical company. LY and FN are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, investigators, and institutions involved in this study. They also thank Yanzhi Hsu for statistical support, Kathy Guarnery for help with figure development, and Mary Dugan Wood for writing assistance.

references

- 1.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(Suppl. 3): iii1–iii9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER stat fact sheets: colon and rectum cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html (22 February 2016, date last accessed).

- 3.National Comprehensive Care Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines®): colon cancer; rectal cancer. Version 2 2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf; http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf (20 November 2015, date last accessed).

- 4.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 1989; 246: 1306–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tugues S, Koch S, Gualandi L et al. Vascular endothelial growth factors and receptors: anti-angiogenic therapy in the treatment of cancer. Mol Aspects Med 2011; 32: 88–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amini A, Masoumi Moghaddam S, Morris DL, Pourgholami MH. The critical role of vascular endothelial growth factor in tumor angiogenesis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2012; 12: 23–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spratlin JL, Cohen RB, Eadens M et al. Phase I pharmacologic and biologic study of ramucirumab (IMC-1121B), a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 780–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn AL et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen LC, Uen YH, Wu DC et al. Activating KRAS mutations and overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor as independent predictors in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuboki Y, Mizunuma N, Ozaka M et al. Grade 3/4 neutropenia is a limiting factor in second-line FOLFIRI following FOLFOX4 failure in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett 2011; 2: 493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shitara K, Matsuo K, Yokota T et al. Prognostic factors for metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing irinotecan-based second-line chemotherapy. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2011; 4: 168–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubicka S, Greil R, André T et al. Bevacizumab plus chemotherapy continued beyond first progression in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy: ML18147 study KRAS subgroup findings. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 2342–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK, Henrichsen-Schnack T et al. The predictive value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol 2014; 3: 852–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Souglakos J, Pallis A, Kakolyris S. Combination of irinotecan (CPT-11) plus 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFIRI regimen) as first line treatment for elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase II trial. Oncology 2005; 69: 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sastre J, Marcuello E, Masutti B et al. Irinotecan in combination with fluorouracil in a 48-hour continuous infusion as first-line chemotherapy for elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 3545–3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H et al. Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4085–4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sehl M, Sawhney R, Naeim A. Physiologic aspects of aging: impact on cancer management and decision making, part II. Cancer J 2005; 11: 461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.