Abstract

The global community’s growing enthusiasm for the potential of social accountability approaches to improve health system performance and accelerate health progress makes it imperative that we learn from social accountability intervention implementation experience and results. To this end, we carried out a review of Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc. (CARE)’s experience with the Community Score Card© (CSC)—a social accountability approach CARE developed in Malawi. We reviewed projects that CARE implemented between 2002 and 2013 that employed the CSC and that had at least one evaluation in English. We systematically collected and synthesized information from evaluations on the projects’ characteristics, CSC-related outcomes and challenges. Eight projects, spanning five countries, met our inclusion criteria. The projects applied the CSC to various focus areas, mostly health. We identified one to three evaluations, mostly qualitative, for each project. While the evaluations had many limitations, consistency of the results, as well as the range of outcomes, suggests that the CSC is contributing to significant changes. All projects reported CSC-related governance outcomes and service outcomes. There is promising evidence that the CSC can contribute to citizen empowerment, service provider and power-holder effectiveness, accountability and responsiveness and spaces for negotiation between the two that are expanded, effective and inclusive. There is also evidence that the CSC may contribute to improvements in service availability, access, utilization and quality. The CSC seems particularly suited to building trust and strengthening relationships between the community and service providers and to improving the user-centred dimension of quality. All of the projects reported challenges, with ensuring national responsiveness and inclusion of marginalized groups in the CSC process proving to be the most intractable. To improve health system performance and accelerate health progress we recommend further CSC use, enhancements and research.

Keywords: Community Score Card, governance, health, social accountability, systematic review

Key Messages

Global interest in social accountability programmes to improve health outcomes has not been matched by empirical data or our understanding of the factors and strategies that influence the functioning of accountability mechanisms. We present a review of programme reports and evaluations to describe CARE’s experience with a social accountability approach, the Community Score Card, and examine related outcomes and challenges.

A review of CARE’s Community Score Card evidence suggests that the Community Score Card prompts a wide range of outcomes and merits further attention as a strategy for improving accountability.

Introduction

Accountability is increasingly called for to improve health system performance and accelerate health progress (Brinkerhoff 2004; United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon 2010; United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon 2015). Accountability encompasses both answerability—the obligation of public officials to provide information about, and explanation for, their actions—and enforcement—the imposition of sanctions in response to the failure of power-holders to uphold their duties (Schedler 1999). In the health sector, accountability mechanisms aim to ensure both answerability and enforcement, and these mechanisms ideally support collaborative solutions. To support collaborative solutions, accountability mechanisms typically must ‘mediate relationships between unequal partners’, addressing issues related to power and representation, and transforming participants’ self-perceptions (George 2003).

The development community has outlined two categories of accountability mechanisms in the health sector—‘external’ mechanisms that aim to regulate answerability between the community and health system and ‘internal’ or bureaucratic mechanisms that seek to regulate answerability between and among different levels of the health system (Brinkerhoff 2004). External accountability mechanisms are part of what the development community often refers to as ‘community accountability’ or ‘social accountability’. Definitions of social accountability vary, but they all centre on the idea of citizen engagement in processes to improve public sector performance and hold service providers and other actors accountable (World Bank 2003). Social accountability approaches began to grow in prominence as a way to achieve good governance and address service delivery failures after the World Bank published their influential 2004 World Development Report, ‘Making Services Work for the Poor’ (World Bank 2003).

Accountability linkages that are primarily internal to the public health bureaucracy and that connect upwards tend to orient actors’ accountability towards bureaucratic superiors, not towards service users (Brinkerhoff 2004); social accountability approaches aim to change this dynamic. This is difficult to do, as health providers often prioritize the demands of government officials and other power-holders over those of service users, given existing oversight mechanisms (Berlan and Shiffman 2011). Local-level accountability between the community and health system is needed to improve the responsiveness and quality of care (Cleary et al. 2013). Focusing on accountability changes within the health system in isolation from community governance structures may lead to missed opportunities to improve services, and conversely, mobilizing the public without properly engaging health personnel may lead to roadblocks to service improvements (George 2003). Striking a balance between both internal and external accountability is important (Cleary et al. 2013).

The potential of accountability approaches to improve services and outcomes compelled some in the development community to conduct research that has allowed us to understand better the factors and strategies that influence provider accountability and the functioning of accountability mechanisms. This research revealed several pre-requisites that are necessary to ensure effective community participation in sexual and reproductive health service improvements, including the following: participation contracts to enhance the power of civil society representatives, quotas for participation of excluded groups and investments in capacity building of different stakeholders on both leadership and reproductive health and rights (Murthy and Klugman 2004). In addition, a review identified three sets of interrelated factors that influence the functioning of health sector accountability mechanisms: differences in (1) values, norms and culture, (2) attitudes and perceptions and (3) resources and capacities of the health service, vs those of citizens and patients (Cleary et al. 2013). Additional research on factors and interventions shaping health provider accountability suggested provider responsiveness could be improved by creating official mechanisms for community participation and empowering them to take actions, by enhancing the quality of the health information available to the community, and including non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in initiatives to expand access to care (Berlan and Shiffman 2011). While current research identifies promising factors and strategies for influencing provider accountability and improving the functioning of accountability mechanisms, the evidence base on the effectiveness of such approaches remains limited.

There has also been increasing interest in social accountability approaches as well as research on their effects, because of the perceived potential of social accountability approaches to improve services and outcomes. As a result, several compelling examples of the effectiveness of social accountability approaches in the health sector have emerged. For example, in Uganda, a participatory monitoring approach resulted in significant improvements in healthcare quality and outcomes, including increases in facility deliveries, family planning utilization, immunizations and infant weight, and reductions in under-five mortality; in Brazil, a participatory budgeting approach resulted in significant decreases in infant mortality (Björkman and Svensson 2009; Bjorkman-Nyqvist et al. 2013; Gonçalves 2013; Touchton and Wampler 2013). Despite these promising results, however, the body of evidence on the effectiveness of these approaches, in the health sector and beyond, remains mixed (Molyneux et al. 2012; Gaventa and McGee 2013; Joshi 2013; Fox 2014).

The global community’s growing enthusiasm for the potential of accountability approaches to accelerate health progress makes it imperative that we learn from social accountability intervention implementation experience and results. The purpose of this article is to contribute to the social accountability evidence base by reviewing Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc. (CARE)’s experience with the Community Score Card© (CSC)—a social accountability approach developed by CARE in Malawi (Kaul Shah and CARE-LIFH Team 2003). The focus of our review of programme reports and evaluations is to describe CARE’s experience across the variety of sectors and contexts in which we have applied this approach and to examine the CSC-related governance, service and development outcomes, as well as implementation challenges. While we are particularly interested in the CSC’s potential in the health sector, we included CSC projects from a range of sectors in our review. We did this because of the limited number of CARE CSC project evaluations available for inclusion in the review, the commonalities in service delivery, regardless of sector, and our interest in understanding CARE’s broad experience and results achieved with the CSC.

CARE’s CSC

CARE first developed the CSC for the ‘Local Initiatives for Health’ (LIFH) project in Malawi, implemented from 2002 to 2005. LIFH aimed to develop a model that could build collaborative capacity between the service users and partner organizations, such as government service providers, through a rights-based framework capable of the following:

I) empowering individuals and the institutions that support them in their communities to analyze their situation and take decisions about their lives, rather than being passive objects of choices made on their behalf; and II) working with different levels of the government to see how best they can meet the needs of communities with respect to the provision of preventive and curative services designed to meet the most critical health needs and rights of rural communities, especially women and disadvantaged groups (Kaul Shah and CARE-LIFH Team 2003).

With this in mind, the LIFH team designed an approach to support the realization of people’s health rights while building sustainable partnerships between service users and providers. The approach integrates several rights-based principles, including the following: access to information; participation in decision-making processes; accountability; transparency; equity; and shared responsibility. This new approach became known as the CSC (Kaul Shah and CARE-LIFH Team 2003).

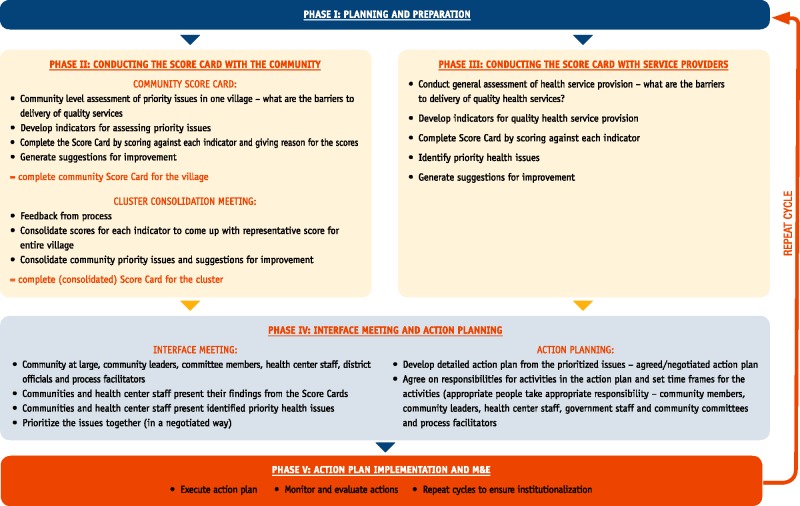

The CSC brings together service users, service providers and local government to identify service access, utilization and provision challenges, to generate solutions and to work in partnership to implement and track the effectiveness of those solutions in an ongoing process of improvement. The CSC approach consists of five phases, repeated every six months for the life of the project (Figure 1) (CARE Malawi 2013):

Figure 1.

Community Score Card methodology.

Phase I: Planning and preparation. This involves identifying the sectoral and geographic scope of the initiative, assessing entitlement gaps, training CSC facilitators and securing cooperation of all participating parties.

Phase II: Conducting the Score Card with the community. This involves focus group discussions (FGDs) with community members (separated into groups such as men, women, youth and others depending on the CSC’s sectoral scope) to identify and prioritize issues (e.g. service access, utilization and quality provision), CSC facilitators and stakeholders clustering similar issues to create the Score Card indicators, communities scoring each indicator and listing reasons for the score and consolidation of Score Cards across communities if needed.

Phase III: Conducting the Score Card with service providers. The service providers essentially go through the same process as the community, outlined under Phase II. Phase III can occur after or concurrently with Phase II. As with the community FGDs, CSC facilitators can group similar types of providers so that those at different levels in the health system feel more comfortable speaking candidly about the issues and barriers they face.

Phase IV: Interface meeting and action planning. This involves community members (i.e. service users), service providers, government staff and additional power-holders coming together to share and discuss the Score Cards and to develop a joint action plan.

Phase V: Action plan implementation and follow-up. This involves action plan implementation, monitoring and evaluation. The community members, service providers, government staff and additional power-holders all have a role to play in this phase. The process is repeated every six months to institutionalize the practice and assess if there has been improvement resulting from action plan implementation.

It is important to bear in mind that the CSC is not about finger-pointing or blaming, and it is not designed to settle personal scores or create conflict within communities. Rather, the CSC helps service users give systematic and constructive feedback to service providers about their performance, while also helping governments and service providers learn directly from communities about which aspects of their services and programmes are working well and which are not. The information that the process generates enables decision-makers to make informed decisions and policy choices and to implement service improvements that respond to citizens’ rights, needs and preferences. Although originally designed for the health sector, CARE has applied the CSC in a variety of ways and in many countries to address a diverse range of issues within different sectors (CARE Malawi 2013).

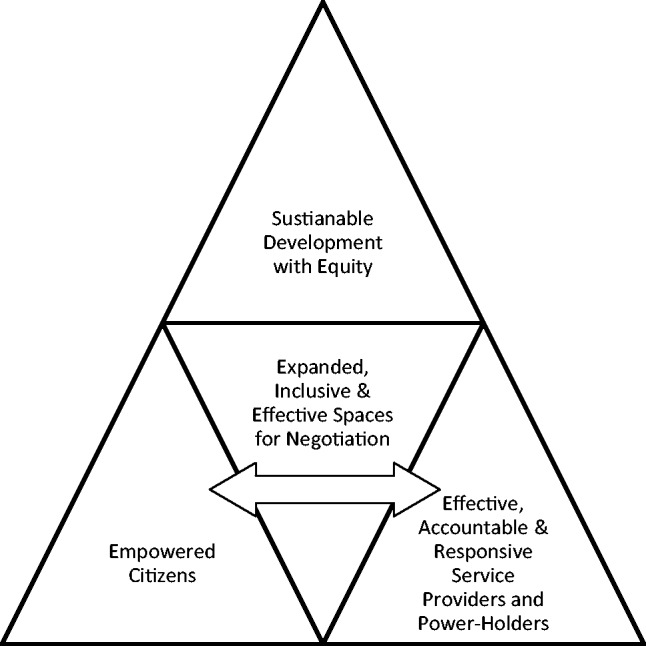

CARE’s Governance Programming Framework (GPF) (Figure 2) guides our CSC work. The GPF outlines three domains necessary to achieve good governance and sustainable and equitable development: (1) empowered citizens; (2) effective, accountable and responsive providers and power-holders; and (3) expanded, inclusive and effective spaces for dialogue and negotiation between the groups. Change needs to take place and be sustained in all three domains to achieve this impact. To cultivate changes in the three domains, CARE employs social accountability approaches, such as the CSC. CARE’s GPF framework emphasizes the importance of the interaction between these parties, and CARE’s role in the process is often to help build and strengthen the systems and spaces where citizens, especially the most vulnerable and marginalized, service providers and power-holders can come together to discuss and resolve issues (CARE 2011).

Figure 2.

CARE’s governance programming framework.

Methods

For this review, we identified all CARE programmes that implemented the CSC, and we located related programme materials and evaluation reports. We identified programmes and materials through requests to CARE governance experts and CARE offices known to have carried out social accountability approaches, as well as through internet searches and searches of CARE International’s evaluation database. Criteria for a programme’s inclusion in the review included the following: CARE implemented the project between 2002 and 2013; the project employed the CSC; and the project had at least one evaluation report in English.

For each CSC project included in this study, we systematically collected information from evaluation documents using a data extraction form. To minimize the potential for bias, the authors discussed any discrepancies in the results of the data extraction until they agreed. Results were shared with CARE country office programme managers for confirmation. Extracted data included the following: the project’s name; location; dates; objective; focus area(s); focus areas(s) to which project staff applied CSC; whether the CSC was the primary strategy the project used to achieve outcomes; the project’s evaluation design; CSC-related outcomes reported in the evaluation; and challenges reported in the evaluation.

We classified the CSC-related outcomes extracted from the programme evaluation documents into four categories: governance; service; human development; and other. If reported outcomes fell within one of the three domains underpinning CARE’s GPF, we categorized them as governance outcomes. This included outcomes that indicated ‘empowered citizens’ (i.e. citizens that demonstrate awareness of their rights, exercise agency, organize or take collective action and hold power-holders to account); ‘effective, accountable and responsive service providers and power-holders’ (i.e. those who have the capacity to uphold rights, are responsive to service users and are transparent and accountable); and ‘expanded, effective and inclusive spaces for negotiation’ (i.e. the existence of mechanisms and spaces for sharing and responding to information and feedback) (CARE 2011).

Service outcomes included changes in service availability, access, utilization and quality, including the following dimensions of quality: safe, effective, user-centred, timely and equitable. We categorized impact-level outcomes such as health impacts and academic achievement as human-development outcomes. Finally, changes that did not fit into the three categories outlined above, we grouped under other outcomes. After assigning the outcomes to their categories, we identified and synthesized key themes. We also identified challenges reported in project documents and identified and synthesized key themes among those challenges.

Limitations

The fact that this review was done by CARE, and was based on CARE project evaluation reports, is a limitation of our methodology. While every effort was made to conduct a fair and balanced review of the programme results, we cannot be certain all potential bias was eliminated. CARE funded all the evaluations for the purposes of programme learning or reporting to donors, which may have led to potential bias towards reporting positive findings. While we made our best efforts to locate and include all evaluations that met the inclusion criteria in the review, there is a chance that negative reports were not shared.

Results

Project characteristics

Our search yielded eight projects that met our criteria for inclusion in this review. Following is a summary of their characteristics, which are detailed in Table 1. Of the eight projects, two were in Malawi, two in Tanzania, two in Ethiopia, one in Rwanda and one in Egypt. The CSC initiatives covered a broad range of geographies and sites. The level of intensity of CSC activities was not clear in projects reports; however, the CSC guidelines call for carrying out the CSC process every six months, so we can assume activities occurred at least this frequently. CARE implemented all of the projects between 2002 and 2013, and they ranged in duration from two to six years. CARE implemented several of the projects in collaboration with other NGOs and civil society organizations (CSOs). The projects applied the CSC to a variety of focus areas, with a majority applying the CSC to the health sector.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of CARE CSC projects

| Project name | Country and areas covered | Project dates | Project focus area(s) | Focus area(s) (s) of CSC application | CSC is the primary strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Initiatives for Health (LIFH) | Malawi (11 health centres in Ntchisi and Lilongwe districts) | 2002–05 | Health | Health | Yes |

| Supporting and Mitigating the Impact of HIV/AIDS for Livelihoods (SMIHLE) | Malawi (3600 stakeholders in Dowa district) | 2004–10 | HIV and AIDS, livelihoods | Livelihoods | No |

| Health Equity Project (HEqP) | Tanzania (8 wards in Magu and Missungwi districts) | 2007–10 | Governance | Health | No |

| Governance and Accountability Project (GAP) | Tanzania (8 wards in 4 districts, i.e. Ilemela, Nyamagana, Sengerema and Ukerewe) | 2008–11 | Governance | Microfinance, gender-based violence, health, education | Yes |

| Getting Ahead | Ethiopia (8 kebeles in Addis Ababa and 4 kebeles in Bahir Dar) | 2007–10 | HIV and AIDS, livelihoods | Livelihoods | Yes |

| Springboard | Ethiopia (8 kebeles in Bahir Dar) | 2007–12 | HIV and AIDS, livelihoods | Health, livelihoods | No |

| Public Policy Information and Monitoring Advocacy (PPIMA) | Rwanda (140 632 beneficiaries across 4 districts, i.e. Gakenka, Gatsibo, Ngororero and Nyaruguru) | 2009–13 | Governance | Health, agriculture, water & sanitation, education, infrastructure | No |

| Local Service Delivery Initiative (LSDI) | Egypt (47 schools in Ismailia city) | 2010–12 | Education | Education | Yes |

In all but two of the projects—the ‘Governance and Accountability Project’ (GAP) and the ‘Public Policy Information and Monitoring Advocacy’ (PPIMA) project—project staff selected the focus of the CSC process. In the GAP and PPIMA projects, the CSC participants selected the focus from a short list of sectors. Half of the projects report the CSC as the primary strategy for improving services; whereas, the other half report using the CSC in concert with other strategies. However, even within the integrated programmes, several highlight the importance of the CSC. For example, the PPIMA project evaluation called the CSC ‘one of the most successful and innovative tools used by PPIMA’ (Dastgeer et al. 2012).

The objective of the first CSC project, LIFH, was to ‘develop innovative and sustainable models to resolve issues of poor health services and access amongst rural communities’ (Kaul Shah M and CARE-LIFH Team 2003). Not surprisingly, the three projects with governance as their primary focus area—the ‘Health Equity Project’ (HEqP), GAP and PPIMA—all have objectives focused on the following: ensuring that government services are influenced by citizens, equitable and pro-poor, and that they include monitoring of service provision, providing feedback on the implementation of services and programmes and influencing resource allocation and policy processes. Both PPIMA and HEqP used multiple strategies, including CSC, to achieve their objectives, whereas the CSC was the only strategy that GAP used.

The ‘Supporting and Mitigating the Impact of HIV/AIDS for Livelihoods’ (SMHILE), ‘Getting Ahead’ and ‘Springboard’ projects all focused on reducing the impact of HIV and AIDS by strengthening livelihoods services and other HIV- and AIDS-related services and safety nets. Getting Ahead used only the CSC to achieve its objective, whereas the other two projects applied multiple strategies. In fact, initially, the SMHILE project staff did not plan to use the CSC; however, a mid-term evaluation revealed that feedback channels between community members and CARE Malawi staff and government service providers were weak. Therefore, SMHILE decided to use the CSC to empower communities to participate and to ensure accountability of decision-making at all levels. Similarly, Springboard used the CSC as a means to address the weak capacity of local government and to promote accountability, transparency, participation and inclusion (Jumbe and Botha 2007). Strengthening relationships between government and CSOs was the primary reason Getting Ahead used the CSC.

The overall objective of the ‘Local Service Delivery Initiative’ (LSDI) was to enhance the quality of performance of basic schools in Egypt. To achieve this objective, project staff used the CSC to strengthen participatory monitoring and performance evaluation of basic schools.

Evaluation characteristics

For each of the projects included in this review, we identified between one and three evaluation sources. Following is a summary of the evaluations’ characteristics that appear in Table 2.

Table 2.

CSC evaluation characteristics

| Project name | Source | Evidence type and description | Evaluation areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIFH | Kaul Shah and CARE-LIFH Team 2003 | Qualitative: Score Card indicator ratings | 2 health centres in Lilongwe |

| CARE Malawi 2005 | Qualitative: 26 FGDs, including: 2 with district health management teams; 3 with health centre staff; 3 with health centre committees; 6 with village health committees; 6 with men; and 6 with women. 120 key informant interviews (KIIs) with household head or proxy. | 3 health centres (1 in Lilongwe and 2 in Ntchisi); 6 villages (2 per health centre) | |

| SMIHLE | Ponsford 2010 | Qualitative: Case study—available secondary data and discussions with CARE staff. | Not specified |

| TANGO International et al 2009 | Qualitative: Data collected from SMIHLE stakeholders, methods and specific stakeholders not clear. | 3 traditional authorities (TAs) in Dowa and 2 TAs in Lilongwe | |

| Altman et al. 2015 | Qualitative: 4 FGDs: 1 with Score Card committee; 1 with women; 1 with local leaders; and 1 with school committee. 1 community dialogue with group village head in Mwaphira community. | Group Village Mwaphira, Dowa district | |

| HEqP | CARE International in Tanzania 2011a | Qualitative: 10 KIIs with CARE HEqP consortium partners, select CARE staff and NGO project stakeholders. Project document review. | Not specified |

| GAP | CARE International in Tanzania 2011b | Qualitative: 6 FGDs with community members (men and women). 25 KIIs with district technical managers, ward and village officers, service providers and civil society officials. | 6 wards across 3 districts (2 in Ilemela, 2 in Ukerewe and 2 in Sengerema) |

| Getting Ahead | CARE Ethiopia Meikle et al. 2010 | Qualitative: Testimonies and observations from CARE staff. | Not specified |

| Springboard | CARE Ethiopia et al. 2012 | Qualitative: 3 FGDs: 1 with girls; 1 with women; and 1 with youth (boys and girls). 21 KIIs with CARE staff, project partners, implementing partners and project beneficiaries (PLWHIV, domestic workers, women, CSWs, health facilities/VCT centres and zonal government)Quantitative: Pre- and post-test design in intervention areas (no comparison), across 5 selected sub-cities, n = 199 (including, youth, aged 15–24, and women) | 5 kebeles in Bahir Dar |

| PPIMA | Dastgeer et al. 2012 | Qualitative: Project document review. PPIMA quarterly review meeting presentations and discussion. Discussions in 2 districts with the following: implementing partners; district administration; service providers; men and women community animators. Site visits and observation at the following at CSC interface dialogue, agricultural land and health centres affected by the project. National-level meetings with national partners, key government collaborators and the European Union Delegation to Rwanda. | Gatsibo and Ngororero districts; Kigali |

| LSDI | CARE Eygpt 2012 | Qualitative: Social workers, the CSC facilitators, assessed the extent to which the programme objectives were met. | 47 schools in Ismailia |

All the evaluations occurred during the project’s lifespan or shortly thereafter with the exception of one of the SMIHLE evaluations (Altman et al. 2015), which occurred two years after the project’s end. Although four of the evaluation papers had limited information about their study design and the qualitative methods used (Dastgeer et al. 2012; TANGO International et al. 2009; CARE Ethiopia et al. 2012; CARE Eygpt 2012), all of the evaluations used qualitative methods that ranged from structured FGDs and interviews, to unstructured discussions and observations. Only one project, Springboard, used a mixed-methods evaluation that included a quantitative component: a population-based survey of women and youth. Of the 11 evaluations that we reviewed, six included community members in their sample, four included CARE staff, four included government officials, four included service providers and three included project implementing partners. There was a broad range of areas the evaluations covered—ranging from two health facilities to multiple districts.

Limitations

The evaluation reports we reviewed were limited in many respects, and only one conducted a quantitative survey to assess programme effects. The weakness of the evaluations’ designs and the largely self-reported and qualitative data included in the evaluations limits our ability to establish causality, to estimate the size of the effects, to rule out other possible determinants, including additional components of the programme and to eliminate bias due to reporting positive results only. Further, we were unable to draw conclusions about the quality of the studies included in the review due to insufficient information on study design, data collection and data analysis. In addition, the evaluations did not report how results were measured. Given the nature of the evaluations, we believe the results reflect what different project stakeholders reported as improvement and not a rigorous assessment of changes that occurred. However, the consistency of the results and the range of outcomes reported are impressive and suggest that the CSC is contributing to significant changes.

CSC-related outcomes

Tables 3 and 4 provide information on CSC-related governance and service outcomes reported in project evaluations and studies.

Table 3.

CSC evaluation-reported improvements in governance outcomes

| Project name | Empowered citizens | Effective, accountable and responsive service providers and power-holders | Expanded, effective and inclusive negotiated spaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIFH |

|

|

|

| SMIHLE |

|

|

|

| HEqP |

|

|

Improved community participation in service delivery |

| GAP |

|

|

|

| Getting Ahead |

|

|

|

| Springboard |

|

|

|

| PPIMA | Improved knowledge of service provider constraints | Increased provider capacity to identify priorities and advocate for resource shifts with higher authorities | Improved community participation in service delivery |

| LSDI | Increased community voice-Improved knowledge of rights to monitor school activities and of social accountability | Increased provider openness and transparency |

|

Table 4.

CSC evaluation-reported improvements in service outcomes

| Project name | Availability | Access and utilization | Service quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIFH |

|

|

|

| SMIHLE |

|

Improved water accessibility owing to increased number of boreholes | Care more user-centred (e.g. power-holders changed seed distribution programme, staffs’ roles and provided new services to meet users’ needs) |

| HEqP | Increased health service utilization | ||

| GAP |

|

|

|

| Getting Ahead | Improved service timeliness (e.g. shorter waiting times for land administration services) | ||

| Springboard |

|

|

|

| PPIMA |

|

|

Increased client satisfaction with health services |

| LSDI | Increased confidence in education services |

Evaluations of all eight projects reported CSC-related governance outcomes across all three domains of the GPF: empowered citizens; effective, accountable and responsive service providers and power-holders; and expanded, effective and inclusive spaces for negotiation (Table 3). A majority of the projects report the CSC led to increases in community voice, including voicing of needs, concerns, feedback and demands, as well as increased confidence to do so. Evidence for increased instances of CSC-related community collective action (ex. construction of a house for health providers) also occurred. Projects reported CSC-related increases in community members holding providers accountable. For instance, in SMHILE, the community reported that its biggest CSC accomplishment was the recovery of money that had gone ‘missing’ from the district assembly to fix the school’s roof. A majority of projects reported CSC-related increases in community members’ knowledge, ranging from knowledge of their rights to knowledge of constraints faced by service providers. GAP evaluations noted that the increased understanding of providers’ constraints led to more realistic expectations among service users and a more sympathetic dialogue with providers. Projects also reported community members exercising their rights and responsibilities (GAP and Getting Ahead) and activation of effective community structures to promote community involvement in service delivery governance (LIFH and SMHILE). In addition, GAP, LIFH and SMHILE all reported that the CSC process helped community members feel more comfortable approaching service providers and power-holders. Community members no longer feared service providers and power-holders, but instead viewed them as partners.

All of the evaluations for all of the projects reported CSC-related improvements in service provider and power-holder effectiveness, accountability and responsiveness. Several projects reported CSC-related increases in provider openness and transparency. For example, providers disclosed budget and financial information to the community (GAP and Getting Ahead). Projects also reported CSC-related increases in service provider accountability, responsiveness and answerability to communities. For example, district officials in the SMHILE project increased investments in forestation, roads and ponds at the request of communities. Projects also reported increases in service provider commitment to their work and capacity owing to the CSC process. For example, Getting Ahead credited the CSC process with empowering service providers by arming them with improved understanding of users’ needs and priorities, which, in turn, gave them increased confidence and credibility to push for improvements within their own organizations and bring attention to gaps. In addition, LIFH evaluations reported CSC-related improvements in health providers’ behaviour and attitudes towards clients, and Springboard evaluations reported that service providers credited service improvements to the involvement of service users through the CSC.

All projects reported CSC-related improvements in expanded, effective and inclusive spaces for negotiation between service providers and the community, including changes in direction, channels, frequency, systems, avenues, spaces and levels of communication. In addition, some projects reported changes in the nature of communication, describing it as more transparent, accountable, inclusive and positive. All the projects reported CSC-related improvements in community participation in services, including increases in monitoring, assessment, planning, decision-making, budgeting, influencing and engagement in policy processes. Several projects reported increased and inclusive meetings between service providers and community members resulting from the CSC process. LIFH, GAP and Getting Ahead evaluations credited the CSC with strengthening relationships between community members and service providers (i.e. increases in partnership, trust and openness).

All of the project evaluations reported CSC-related service outcomes. Five projects reported CSC-related changes in service availability (Table 4). These changes included improvements in health providers’ and teachers’ punctuality and observation of official working hours, increased availability of supplies and equipment, and increases in qualified health providers at facilities. Two projects (SMHILE and PPMIA) reported that, as a result of the CSC, frontline government workers began visiting the community on schedule. Four projects reported CSC-related infrastructure improvements—for example, the construction and refurbishment of health staff houses and health facilities (LIFH, GAP) and improvements to communication facilities and infrastructure (LIFH, PPIMA).

Five of the projects reported changes in service access and utilization (Table 4). LIFH reported that the CSC process resulted in increased utilization of health services, including increases in pregnant women delivering at health facilities and community members seeking treatment for illnesses at health centres. In addition, Springboard suggested that the CSC process resulted in easier access to voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) services, leading to increases in the number of VCT recipients per day. Three projects reported CSC-related changes in how services were delivered, making them more accessible; for example, PPIMA and SMHILE both reported CSC-related increases in the number of boreholes, resulting in more accessible water.

A majority of the projects reported CSC-related changes in service quality (Table 4). Four projects reported services to be more user-centred, respectful and responsive to users’ needs. In addition, evaluations reported improvements in service timeliness, cleanliness and effectiveness. For example, to improve service effectiveness, Springboard strengthened training and mentoring of health professionals and introduced a quality assurance mechanism in health centres. CSC-related improvements in service equity were also reported (LIFH and GAP), including reductions in preferential treatment and discrimination in the provision of services. Evaluations also revealed CSC-related increases in client satisfaction, confidence in services and trust in services.

Only three of the eight projects reported CSC-related development outcomes, all of which were anecdotal. HEqP reported improvements in health outcomes, including maternal health, while PPIMA reported better crop harvests, and LSDI reported higher student academic performance.

Only two (SMHILE, Getting Ahead) of the eight projects reported CSC-related other outcomes, both pertaining to CSC sustainability. A study for SMHILE (Altman et al., 2015), conducted two years after the project’s end, reported community-driven sustainability of the CSC process and related outcomes, as well as spread of the CSC to new applications and geographies. The Getting Ahead evaluation reported that service providers advocated for the government to adopt the CSC and that the head of the municipality had endorsed further expansion of the CSC; however, it is not known if expansion occurred, as CARE no longer has project staff in the area to follow up.

Challenges

All projects reported CSC-related challenges. Projects faced challenges in the following areas: securing and maintaining CSC stakeholder commitment, quality of CSC facilitation, addressing equity issues, implementing under short project timeframes, igniting national government responsiveness and monitoring and evaluation.

Challenges securing and maintaining CSC participation and commitment from CSC stakeholders were reported (PPIMA, Getting Ahead, Springboard, HeqP). The Getting Ahead project noted that community members, CARE staff and partner organizations were reluctant to evaluate government services at first, fearing retribution from authorities. The project overcame this challenge by ensuring government partners and community members were clear on the alignment of the CSC with government accountability initiatives. In the Getting Ahead project, the high level of sub-national government staff turnover made securing commitment an ongoing challenge. The success of the CSC process is highly dependent on the quality of the facilitator and his or her ability to draw out the community’s views, manage power relations, manage time, keep the process focused on consensus building and steer the process away from fault-finding (SMHILE, Getting Ahead). In Getting Ahead, some of the CSC facilitators faced challenges keeping the dialogues focused on building relationships and trust between stakeholders. PPIMA noted that it is challenging to check the quality of a CSC facilitators’ performance systematically. To overcome these challenges, SMHILE required facilitators to have training on the theory underpinning the CSC, the CSC process, local power relations and how to adapt the CSC to the local context.

In the Malawi projects (LIFH, SMHILE), CARE used the CSC to address service equity issues; however, the projects reported difficulty ensuring socially excluded community members’ inclusion in the CSC process and in determining whether the Score Card is representative of everyone’s views.

Several projects (LIFH, HeqP, GAP and PPIMA) reported that the CSC process failed to ignite national government responsiveness, which was attributed to the CSC process not placing enough emphasis on national-level advocacy and engagement. This was seen as problematic, as the CSC process raises community members’ expectations and demand for services. The reasons cited for failure to engage in national-level advocacy included a lack of understanding of the decentralized government system and how to influence it (PPIMA), the perceived complexity of national-level advocacy (HeqP) and challenges in aggregating Score Cards across sites given site specific CSC indicators (PPIMA). In addition, a couple of projects (PPIMA, Getting Ahead) noted the missed opportunities to catalyse institutional commitments, as they did not plug into existing government accountability and participation mechanisms.

Not surprisingly, projects (HeqP, LIFH) also highlighted CSC monitoring and evaluation challenges, which made advocacy efforts more challenging.

Discussion

Our review of > 10 years of experience with CARE’s CSC suggests the CSC has been successfully adapted and used in a wide variety of geographies and sectors, prompting a wide range of outcomes. The project evaluations, mostly qualitative, included in this review reflect project stakeholder’s reported improvements, rather than a rigorous assessment of changes that occurred. Despite the evaluations’ limitations, the consistency of the results and the range of outcomes reported are impressive and suggest that the CSC contributes to significant governance- and service-related outcomes.

All projects reported CSC-related improvements in citizen empowerment, service provider and power-holder effectiveness, accountability and responsiveness, and expanded, effective and inclusive spaces for negotiation between the two. A recent review of the empirical evidence for social accountability argues that ‘more promising results emerge from studies of multi-pronged strategies that cultivate enabling environments for collective action and bolster state capacity to actually respond to citizen voice’ (Fox 2015). This is promising news, as several CSC projects reported that the CSC prompted community collective action and increased service provider and power-holder capacity and responsiveness to community members. However, it is important to note that government responsiveness occurred at the local level, not at the national level.

Another promising finding is that the CSC evaluations reported the presence of all the factors identified in a review carried out by Cleary et al. 2013 as influencing the functioning of accountability mechanisms (i.e. resources and capacity; attitudes and perceptions of actors; and values, beliefs and culture). While one could perceive these factors as pre-conditions to a functioning accountability mechanism, interestingly, the CSC evaluations reported them as CSC-related outcomes. For example, several projects suggested that the CSC unlocked resources (human, material, financial) from the system, improved the ability of citizens to hold providers to account, improved the relationship between providers and citizens and shifted power to citizens.

Our review revealed that the CSC may be able to address challenges that accountability mechanisms face in the health sector. Some of the challenges to achieving accountability in the health sector are the asymmetries in information, access to services and expertise among service users, health providers and oversight groups (Brinkerhoff 2004). The CSC may hold potential to overcome these challenges as several projects included in the review reported CSC-related increases in citizens’ knowledge and service provider and power-holder openness, transparency and communication with citizens. Another challenge threatening the health system’s accountability to citizens is the potential for internal accountability mechanisms to overshadow community mechanisms (Berlan and Shiffman 2011; Cleary et al. 2013). Our review revealed that the CSC may be able to guard against this overshadowing, ensuring service provider and power-holder accountability and responsiveness to citizens. We believe a couple of factors may have helped ensure accountability to citizens in CARE CSC projects. One, the CSC process includes community member- and service provider-defined indicators to focus and drive improvement efforts, which Berlan and Shiffman 2011 propose may hold promise in changing the oversight dynamics and encourage accountability to consumers. Also, the CSC process brings higher-level authorities and decision-makers (ex. District Health Management Team) into the CSC process in an effort to ensure accountability and responsiveness of the entire system, not simply the provider.

A majority of evaluations also reported CSC-related improvements in community member and service provider negotiated spaces, communication, collaboration and relationships. This is important because social accountability initiatives are more likely to be effective if they avoid oppositional tactics and focus on improving communication, shared expectations and collaboration between communities and power-holders (Gaventa and Barrett 2012). A review of social accountability projects in Africa concluded that we need to start thinking about social accountability in a new way—‘social accountability as learning to build trust-based relationships’. The review went so far as to say that, ‘Africa’s future lies in finding the key ingredients to build relationships based on trust’ (Tembo 2013). CARE’s CSC evidence base suggests that the CSC may be one powerful approach for achieving that aim. Interestingly, the promising CSC elements described above were intentionally built into the CSC’s design by the CSC innovators (Kaul Shah and CARE-LIFH Team 2013).

This review also opened our eyes to the many benefits that the CSC can deliver to service providers. Several projects reported CSC-related benefits to providers ranging from increased capacity to advocate for shifts in resources to increased support from community members. As health providers often face unsupportive work environments in the countries of greatest need (Chen et al. 2004), the CSC’s capacity to empower health providers to save lives could be a powerful contribution to practice.

CARE CSC projects reported a broad range of CSC-related improvements in service availability, access, utilization and quality. A majority of projects reported CSC-related service quality improvements, mostly increases in user-centred care, timely care and equitable care; whereas, CSC-related improvements in service safety and effectiveness were limited. This may be because identifying and solving service effectiveness and safety issues often require technical knowledge that community members do not possess. In addition, improving effectiveness and safety may require a higher-level support and more resources. Improvements in user-centred care, timely care and equitable care were mainly improved through provider behaviour change and required few resources. These findings may suggest that the CSC is best placed to address service quality issues, which service users’ experience can inform and are largely within providers’ sphere of control. Our review suggests that the CSC is most effective at improving the user-centred dimension of quality, a realm in which it is often challenging to affect change. CARE projects report that CSC improves the user-centred dimension of quality in several ways, including increasing respectful treatment of patients by health providers. This is an exciting finding since we know that provider attitude is an important factor affecting service utilization, for example, whether or not women deliver in facilities with skilled providers (Kruk et al. 2009).

Several projects also reported CSC-related improvements in service availability, access and utilization. These improvements ranged from changes in provider behaviour (showing up to work on time, observing official working hours and visiting the community on a regular schedule) to increases in staff, supplies, equipment and infrastructure. These findings suggest that the CSC was not only able to initiate improvements requiring provider responsiveness, but also improvements requiring responsiveness and resources from local-level authorities (i.e. increases in staff, etc.). Similarly, just over half the projects reported CSC-related service accessibility improvements that required responsiveness and resources from higher-level officials. In addition, three projects reported increases in utilization of health services, which is an encouraging finding, as it suggests the CSC may be able to change community members’ health-seeking and utilization behaviour.

All of the projects included in the review reported challenges that, if not proactively and properly addressed, could limit the effectiveness of the CSC process. While projects reported overcoming a majority of these challenges, addressing equity issues and igniting national government responsiveness proved particularly challenging to overcome. Research suggests that accountability initiatives need to question ‘who is represented and who may have been left out in order to ensure that policy and program structures do serve the cause of equity’ (George 2003). While some CSC projects included in this review did pursue this line of questioning, they were unable to determine whether the CSC process had adequately represented marginalized groups. The CSC approach does make an effort to ensure that segments of the community with less power are given a voice in the process (ex. having separate focus groups for women in the issue generation process); however, it is unclear whether the most marginalized participate and have a voice.

Several projects also reported that the CSC process failed to ignite national government responsiveness, which was attributed to the CSC process not placing enough emphasis on national-level advocacy and engagement. This is problematic, as some service delivery issues raised through the CSC process require a higher-level response. Some ideas on how to overcome this challenge include using common Score Card indicators across sites so information can be aggregated and shared at the national level and plugging into existing government accountability mechanisms; however, a robust CSC strategy to ensure national government engagement has not yet been developed.

In addition, projects highlighted CSC monitoring and evaluation as a challenge. Despite more than a decade of experience implementing the CSC, CARE’s evidence base on the CSC is limited. Several projects noted that there were no donor funds for an evaluation. In addition, many of the evaluations were conceptualized and implemented at the end of the project and under time constraints. To overcome these challenges, NGOs should advocate for greater investment in evaluation of programmes and approaches. In addition, a clearly articulated programme model, theory of change, research agenda, common measures and academic partnerships would support NGOs to improve the assessment of their approaches and contribute to the broader evidence base. To this end, CARE has developed a CSC health theory of change and measures (Sebert Kuhlmann et al. 2016).

As a majority of the evaluations included in our review had limitations and were qualitative, we must interpret these results with appropriate caution; however, given the many and varied reports of change across multiple dimensions and outcomes, we strongly recommend further use and research on the CSC. Future qualitative research and realist evaluations are needed to explore further the CSC’s outcomes as well as the mechanisms through which these outcomes are achieved and the factors that influence the achievement of these outcomes. One of the values of a realist evaluation is its ability to provide insight into how an intervention works within a complex and changing context. Understanding the conditions under which an approach like the CSC is most successful, for whom it works and for what kinds of issues would be enormously valuable. For example, we are currently attempting to adapt the approach for use with prevention of mother to child transmission services, and questions about if, when and how to engage and give voice to women and families who are sometimes marginalized or stigmatized both within the health system as well as the community, provides particularly interesting, and important, challenges to accountability efforts. To maximize the impact of the CSC we must also explore how to effectively link the CSC to the national level, how to scale the approach and how to ensure the approach delivers benefits to marginalized groups.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sall Family Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of CARE Malawi, CARE Ethiopia, CARE Egypt, CARE Rwanda, CARE Tanzania and CARE UK for providing CSC programme documents and reviewing the findings. They acknowledge the particular contributions of Thumbiko Msiska, Lemekeza Mokiwa, Simeon Phiri and Constance Mzungu (CARE Malawi); Anteneh Gelaye (CARE Ethiopia); Jean Claude Kayigamba (CARE Rwanda); Raymond Nzali, Rachael Boma and Edson Lassy Nyingi (current and former CARE Tanzania staff); Maria Cavatore, Muhamed Bizimana and Gaia Gozzo (CARE UK). They also thank Elisabeth Murkison and Anne Laterra for providing editorial support.

References

- Altman L, Gullo S, Cavatore M, et al. 2015. “You are not performing well, you can go!” Evidence for the long-term sustainability of CARE’s Community Score Card and its effects in Malawi. Draft paper.[TQ1][TQ2]

- Berlan D, Shiffman J. 2011. Holding health providers in developing countries accountable to consumers: a synthesis of relevant scholarship. Health Policy and Planning 27: 271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman-Nyqvist M, de Walque D, Svensson J. 2013. Information is power: experimental evidence of the long run impact of community based monitoring. Working Paper. https://editorialexpress.com/cgibin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=NEUDC2013&paper_id=312

- Björkman M, Svensson J. 2009. Power to the people: evidence from a randomized field experiment of a community-based monitoring project. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124: 735–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff DW. 2004. Accountability and health systems: toward conceptual clarity and policy relevance. Health Policy and Planning 19: 371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARE. 2011. Towards Better Governance: A Governance Programming Framework for CARE London, England: CARE International UK. [Google Scholar]

- CARE Ethiopia, CARE Canada, Takele Y. 2012. End-term evaluation report: springboard project – building on experiences and lessons learnt to further impact in combating HIV and AIDS.

- CARE Ethiopia Meikle A. 2010. The community scorecard in ethiopia: process, successes, challenges, and lessons learned.

- CARE Eygpt. 2012. Final implementation report Community Score Cards pilot, Ismailia, Egypt. Cairo, Egypt: CARE Egypt [Google Scholar]

- CARE International in Tanzania. 2011a. Health equity project final evaluation.

- CARE International in Tanzania. 2011b. “We now have our power back!” Governance and Accountability Project (GAP): the perceptions of project participants about its performance. An Internal Final Evaluation Report.

- CARE Malawi. 2005. Lessons and Experiences from Local Initiatives for Health (LIFH) Project: final evaluation report.

- CARE Malawi. 2013. The Community Score Card (CSC): A Generic Guide for Implementing CARE’s CSC Process to Improve Quality of Services. Lilongwe, Malawi: Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, et al. 2004. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. The Lancet 364: 1984–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary SM, Molyneux S, Gilson L. 2013. Resources, attitudes and culture: an understanding of the factors that influence the functioning of accountability mechanisms in primary health care settings. BMC Health Services and Research 13: 320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastgeer A, Bourque A, Kimenyi A. 2012. Indevelop AB in corporation with GRM. Final report: evaluation of the Sida and DFID funded Public Policy Information, Monitoring and Advocacy (PPIMA) project in Rwanda.

- Fox J. 2015. Social accountability: what does the evidence really say? World Development. 72: 346–361 [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa J, Barrett G. 2012. Mapping the outcomes of citizen engagement. World Development 40: 2399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa J, McGee R. 2013. The impact of transparency and accountability initiatives. Development Policy Review 31: s3–28. [Google Scholar]

- George A. 2003. Using accountability to improve reproductive health care. Reproductive Health Matters 11: 161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves S. 2013. The Effects of Participatory Budgeting on Municipal Expenditures and Infant Mortality in Brazil. World Development. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.009

- Joshi A. Do they work? Assessing the impact of transparency and accountability initiatives in service delivery. Development Policy Review 2013;31:s29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jumbe CBL, Botha B. 2007. Mid-term Evaluation Supporting and Mitigating the Impact of HIV/AIDS for Livelihood Enhancement (SMIHLE): A Project Implemented by CARE International in Malawi. Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul SM; CARE-LIFH Team. 2003. Using Community Scorecards for Improving Transparency and Accountability in the Delivery of Public Health Services: Experience from Local Initiatives for Health (LIFH) Project. Lilongwe, Malawi: CARE-Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Paczkowski M, Mbaruku G, de Pinho H, Galea S. 2009. Women's preferences for place of delivery in rural Tanzania: a population-based discrete choice experiment. American Journal of Public Health 99: 1666–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux S, Atela M, Angwenyi V, Goodman C. 2012. Community accountability at peripheral health facilities: a review of the empirical literature and development of a conceptual framework. Health Policy Planning 27: 541–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy RK, Klugman B. 2004. Service accountability and community participation in the context of health sector reforms in Asia: implications for sexual and reproductive health services. Health Policy and Planning 19: i78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsford R. 2010. ALINe Farmer Voice Awards CARE Malawi Case Study. http://pool.fruitycms.com/aline/Downloads/Care-Malawi.pdf

- Sebert Kuhlmann A, Gullo S, Galavotti C, et al. 2016. Women’s and Health Workers’ Voices in Open, Inclusive Communities and Effective Spaces (VOICES): measuring governance outcomes in reproductive and maternal health programmes. Development Policy Review.

- Schedler A. 1999. Conceptualizing accountability In: Schedler A, Diamond L., Plattner M.F. (eds). The Self-Restraining State Power and Accountability in New Democracies. Boulder, Co: Lynne Rienner, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- TANGO International, Caldwell R, Downen J, Langworthy M. 2009. Final evaluation report: Poverty Alleviation through Civil Society Strengthening (PACS). CARE Australia. Tucson, Arizona: TANGO International. [Google Scholar]

- Tembo F. 2013. Rethinking social accountability in Africa: lessons from the Mwananchi programme. London: ODI; http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/7669-mwananchi-social-accountability-africa [Google Scholar]

- Touchton M, Wampler B. 2013. Improving social well-being through new democratic institutions. Comparative Political Studies http://cps.sagepub.com/content/47/10/1442.full.pdf+html

- United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. 2010. Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health. New York, NY: United Nations; http://www.everywomaneverychild.org/images/content/files/global_strategy/full/20100914_gswch_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. 2015. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health. New York, NY: United Nations; http://globalstrategy.everywomaneverychild.org/pdf/EWEC_globalstrategyreport_200915_FINAL_WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2003. World development report 2004: making services work for poor people. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press/World Bank. [Google Scholar]