Abstract

Introduction This research examines the institutional dynamics of tobacco control following the establishment of Kenya’s 2007 landmark tobacco control legislation. Our analysis focuses specifically on coordination challenges within the health sector.

Methods We conducted semi-structured interviews with key informants (n = 17) involved in tobacco regulation and control in Kenya. We recruited participants from different offices and sectors of government and non-governmental organizations.

Results We find that the main challenges toward successful implementation of tobacco control are a lack of coordination and clarity of mandate of the principal institutions involved in tobacco control efforts. In a related development, the passage of a new constitution in 2010 created structural changes that have affected the successful implementation of the country’s tobacco control legislation.

Discussion We discuss how proponents of tobacco control navigated these two overarching institutional challenges. These findings point to the institutional factors that influence policy implementation extending beyond the traditional focus on the dynamic between government and the tobacco industry. These findings specifically point to the intragovernmental challenges that bear on policy implementation. The findings suggest that for effective implementation of tobacco control legislation and regulation, there is need for increased cooperation among institutions charged with tobacco control, particularly within or involving the Ministry of Health. Decisive leadership was also widely presented as a component of successful institutional reform.

Conclusion This study points to the importance of coordinating policy development and implementation across levels of government and the need for leadership and clear mandates to guide cooperation within the health sector. The Kenyan experience offers useful lessons in the pitfalls of institutional incoherence, but more importantly, the value of investing in and then promoting well-functioning institutions.

Keywords: Government, health policy, institutions, policy implementation, tobacco

Key Messages

Policy implementation is influenced by intra-governmental coordination and cooperation.

Frameworks that have used to analyse tobacco control policy development and implementation have largely focused on the dynamics between government and tobacco industry interests.

Our findings point to the need to expand this framework to include institutional and bureaucratic elements.

These elements contribute to a more robust understanding of the barriers and facilitators of policy implementation.

Introduction

Tobacco use is a major risk factor for every major non-communicable disease and is responsible for roughly 6 million premature deaths annually (Eriksen et al. 2015). A large and increasing proportion of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where comprehensive tobacco control measures remain largely nascent. Governments around the world recognize that the most effective broad strategy to fight the tobacco epidemic is through effective population-level policies, and have enshrined many of them—including smoke-free places, warning labels, tobacco taxes and marketing bans—in the 2005 World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), to which 180 countries are now a party. The WHO FCTC provides direction not just on substantive policy content, such as provisions dealing with warning labels or taxation, but mandates the establishment of governance mechanisms. The text of the treaty urges countries to establish both an intersectoral coordination mechanism and a national focal point (which may be represented by the intersectoral coordination mechanism) to serve as a conduit for international–national alignment and as an institution that fosters policy coherence. Implicit in these governance provisions is the recognition that institutions matter for successful tobacco control. This recognition is intuitive given that policy measures require institutional support. Countries, like Kenya, who have ratified the WHO FCTC must now find ways to build institutions to foster the implementation of the treaty in a way that reflects a whole-of-government approach. What is important to consider is that even within the health sector these institutional arrangements may disrupt traditional ways of working, thus requiring concerted attention to coordinate with these new institutions. Though a number of countries have established these institutions, including several notable ones in LMICs (e.g. Costa e Silva et al. 2013; Bialous et al. 2014; Lencucha et al. 2015a), beyond some ‘how-to’-type documents (e.g. CTCA 2013), there has been little research on how these institutions disrupt or reorient previous ways of governing, despite the recognition that institutions matter (Isett 2013; Xiao et al. 2015).

In this article, we examine the key coordination challenges within government in the development and implementation of tobacco control policy in Kenya. Governance continues to be of primary importance to strengthening tobacco control policy, and coordination among different actors remains a pivotal component of good governance (Greer and Lillvis 2014). Governance refers to how issues of public import are managed within government and among government and non-governmental actors such as civil society organizations and the commercial sector (Stoker 1998). This study focuses on two dimensions of policy coordination within government. Governments and even ministries within government are not monolithic and typically house a highly complex institutional milieu (Duit and Galaz 2008). Complexity in this case refers especially to multiple actors managing distinct but overlapping issues within government. For example, tobacco control legislation at the federal level, dealing with issues such as taxation, smoke-free spaces and tobacco packaging requirements, must be taken up by different offices within the Ministry of Health (MOH), across ministries, and by different levels of government in order to have any meaningful impact on population health. Implicit in this complex institutional environment is the need for actors to interact and align their efforts, a crux for successful governance.

It is often this complexity that creates challenges for policy development and implementation. We draw from the matrix of coordination forms developed by Christensen and Lægreid (2008) to highlight challenges that exist within the Kenyan government in managing tobacco control. Specifically, we focus on internal coordination, which involves coordination within the central government and is distinguished from external coordination, which involves coordination between government and non-state actors. Internal coordination can be both horizontal and vertical. Internal–horizontal coordination involves ‘coordination between different ministries, agencies or policy sectors’ (Christensen and Lægreid 2008). Although intersectoral governance is a critical dimension in the field of tobacco control, in this article, we focus on coordination challenges and opportunities within the health sector.

In the context of Kenya, within the MOH, there exist different agencies and offices, including the newly established Kenya Tobacco Control Board (KTCB), which serves as an advisory board for the implementation of the Tobacco Control Act 2007 (Republic of Kenya, 2007b). We treat this dimension as horizontal because we explore the relationships among these parallel offices within the MOH. Internal–vertical coordination involves coordination ‘between (the) parent ministry and subordinate agencies and bodies in the same sector’ (Christensen and Lægreid 2008). In our case, we examine the relationship between the national and county level, and particularly the devolution resulting from the implementation of Kenya’s new constitution in 2010 (Cheeseman et al. 2016).

This research charts important theoretical territory. Assessment of health policies has for a long time over-emphasized the technical content and design, often neglecting institutions, actors and processes that are involved in developing and implementing policy decisions, and taking insufficient account of the context in which the policy decisions are made or enacted (Walt and Gilson 1994; Gilson and Mills 1995; Gilson and Raphaely 2008). In the tobacco control literature specifically, scholars have typically placed the main theoretical and substantive emphasis on the key private economic interest: the tobacco industry (Saloojee and Dagli 2000; Yach and Bettcher 2000). Although tobacco interests have played and continue to play a central role in resisting tobacco control, there is now a growing recognition that coordination within the health sector and between levels of government also play a crucial role in the success of tobacco control policy development and implementation (Studlar 2007; Studlar and Cairney 2014). Too frequently, scholars have not sufficiently elucidated the institutional landscape within which these actors must operate.

Within-government coordination is important for many reasons including providing benefits such as cost sharing by pooling resources (Vangen and Huxham 2003; Lundin 2007), enhanced policy coherence (Kavanagh and Richards 2001; De Alba 2012), accountability (Wilkins 2002) and clear goal-setting (Cassels 1995). As scholars note, accountability itself has several key components including financial, performance and political (Brinkerhoff 2003). By focusing on the institutions involved in policy reform, we are also able to examine the actual policy process, thereby helping to explain why desired policy outcomes either occur or fail to emerge. An empirical gaze directed at institutions also has implications for the sustainability of policy initiatives insofar as institutions can insulate policy decisions from forces that attempt to weaken policy outcomes. For example, along with substantive tobacco control policies such as taxation, public smoking bans and age restrictions, governments such as Brazil have created rules to govern the process of stakeholder interaction, particularly between government and the tobacco industry (Costa e Silva et al. 2013). Moreover, as we noted at the outset, many types of policies that governments must develop and implement involve different agencies or offices within the MOH and across different levels of government and it is useful to consider abstractly the general complexities surrounding policy reform and implementation.

Kenya presents a robust case study for evaluating intra-governmental cooperation because it has one of the longer-standing tobacco control coordinating mechanisms in a LMIC, and particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, after passing comprehensive legislation in 2007, which included the establishment of a national coordinating mechanism, Kenya has struggled to pass corresponding regulations, and coordination and cooperation among the different government actors responsible for tobacco control remains salient. A report published by the WHO in 2012 about the state of tobacco control in Kenya points to the need to address intersectoral coordination challenges, highlighting that ‘roles of different tobacco control stakeholders have not been articulated’, and that ‘Evidence of conflicting interpretations of the Tobacco Control Act at the different ministries points to the need for a stronger inter-ministerial collaboration and finalization of the regulations for implementation of the Act’ (WHO 2012a).

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with key tobacco control stakeholders (n = 17), including policy makers, representatives from intergovernmental organizations, ministry officials, members of the Kenya Tobacco Control Board (KTCB), civil society actors and journalists, as illustrated in Table 1. We used purposive sampling to recruit stakeholders who have been and are currently involved in tobacco issues including tobacco-related economic activity and policy and tobacco control (Miles and Huberman 1994). We also used snowball sampling whereby we asked participants to recommend individuals who they thought would contribute information to the study (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981; Noy 2008). At least two investigators were present at each interview. Recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and transcripts were entered into NVivo qualitative software for analysis. For the interviews that were not recorded, both investigators took notes and compared these notes for accuracy following each interview. Notes were also entered into NVivo for analysis. The data were coded for salient themes. We utilized the constant comparative method to identify themes that were supported by data across the different interviews (Boeije 2002). To enhance the trustworthiness of our findings, we present direct quotes from participants in the presentation of our findings. Last, we worked to construct a defensible narrative using the themes in order to articulate the salient challenges being experienced in Kenya. The bulk of this narrative walks the reader through the major challenges that emerged during the establishment and implementation of the tobacco control regulations. The authors obtained ethics approval from their institution.

Table 1.

List of key informants and institutional affiliation

| Participants | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Government | |

| 1–2 | EAC, Commerce and Tourism |

| 3–4 | Foreign Affairs and Trade |

| 5 | Health |

| 6 | Agriculture |

| 7–9 | Finance and Investment and Brand Kenya |

| 10 | County health official |

| 11–12 | Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Control bodies |

| Non-governmental Organizations | |

| 13 | Tobacco Control Alliance |

| 14 | Policy advocacy |

| 15 | Research and Academia |

| 16 | Journalist on tobacco issues in Kenya |

| 17 | Intergovernmental Organizations |

Analysis

Coordination and mandate challenges within government

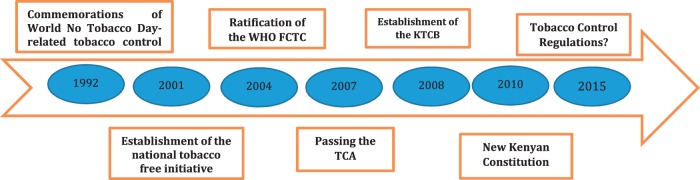

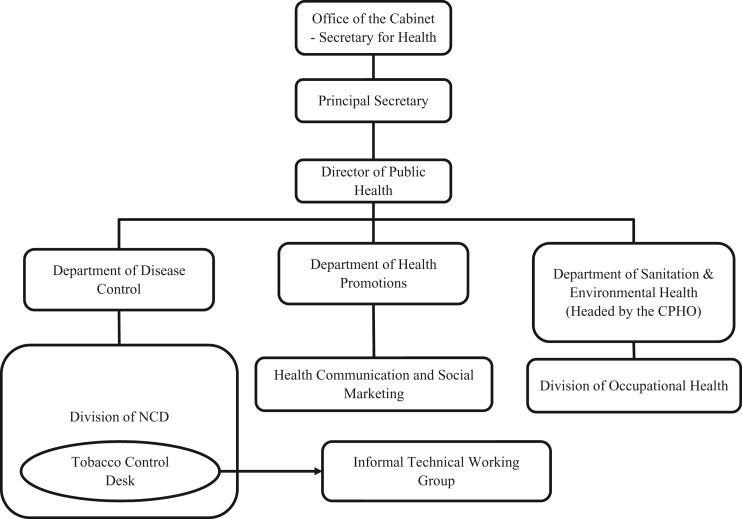

The TCA, passed by parliament following a long series of concerted efforts by tobacco control proponents beginning in the early 1990s (see Figure 1 below), positions the MOH as the focal point for tobacco control coordination in Kenya. In order to contextualize tobacco control governance in Kenya, we begin with a brief description of the organizational structure of the MOH. As Figure 2 illustrates, the cabinet secretary, appointed by the head of state, leads the MOH and serves to ensure that cabinet decisions, legislation and regulations on health are implemented. Immediately under the minister serves the principal secretary of health who is the accounting officer ensuring monies allocated to the ministry are used prudently. Under the principal secretary is the director of public health whose role is to supervise the departments and the divisions within them (Republic of Kenya 2007a).

Figure 1.

Kenya Tobacco Control Timeline, 1992–2014. Source: Adapted from WHO Tobacco Control Needs Assessment, 2012.

Figure 2.

Composition and Organizational Structure of the MOH Tobacco Control Programme. Source: Adapted from WHO 2012.

Two different units within the MOH are charged with implementing tobacco control: the non-communicable disease (NCD) division and the office of the chief public health officer (CPHO). The NCD division typically addresses the issues involving the international community. For example, a department staff member currently serves as elected chair of Africa’s region of the WHO FCTC Conference of the Parties, and historically, this division has been involved in negotiating the WHO FCTC on behalf of Kenya. The tobacco control desk and informal technical working group that coordinate this effort are housed in this office. One non-governmental informant confirmed this historical fact: ‘The history, experience and general push for tobacco control initiatives in Kenya was done by the division of non-communicable diseases and civil society’ (participant 14). This division also manages information gathering and dissemination at the international level pertaining to the status of tobacco control policies in Kenya. In terms of implementation of tobacco control at the country level, however, the CPHO has the mandate to take the lead role. Within the office of the CPHO, the TCA establishes a secretariat that coordinates tobacco control initiatives. Therefore, organizationally, the office of the CPHO and the division in charge of NCDs each has a distinct role in tobacco control. Commentators on whole-of-government approaches to public administration note that this specialization is not merely an expression of an ‘obsolescent’ institutional legacy, given that a division of labour is an ‘inevitable feature of modern organizations’ (Christensen and Lægreid 2008). In other words, specialization within different offices emerged as an important feature of bureaucratic structure in order to increase efficiency, clarify mandates and concentrate technical and topical expertise within distinct government institutions. However, we return to a point made earlier that the need for horizontal and vertical coordination in the area of tobacco control necessarily disrupts previous ways of operating, where silos within government are no longer desirable or effective to develop and implement comprehensive measures.

In addition to these two units, the TCA also establishes the Kenya Tobacco Control Board (KTCB), which is charged with the mandate of advising the MOH on tobacco control issues. The KTCB is granted broad advisory capacity, including to ‘advise the Cabinet secretary on the national policy to be adopted with regard to the production, manufacture, sale, advertising, promotion, sponsorship and use of tobacco and tobacco products’ and, importantly, the ‘formulation of the regulations’ (Republic of Kenya 2007b). The KTCB is chaired by an individual appointed by the cabinet secretary for health and establishes a broad membership including a representative from the Ministry of Agriculture, civil society and health professional organizations. The CPHO or a representative from this office serves as secretary of the KTCB. Importantly, the TCA explicitly protects the KTCB from industry representation: ‘No member of the Board shall directly or indirectly be affiliated to the tobacco industry or its subsidiaries’ (Republic of Kenya 2007b).

In order to fully implement the TCA, there was need for the MOH to develop regulations that would require parliamentary approval. But, discordance among the different entities charged with tobacco control surfaced almost immediately, which is reflected in the eight years that the MOH took to develop regulations. The regulations were not submitted to the government register, the Gazette, until December 2014. Some informants expressed concern that the KTCB itself was stalling the movement of the regulations through parliament. One informant stated emphatically: ‘Some of the early giants in tobacco control sitting in the board have records that show that they have changed… they don’t push forcefully for good tobacco control policies … real life is different than it is on paper… people aren’t always what they seem’ (participant 5).

In contrast to this interpretation, one member of the KTCB explained the long delay by noting that they wanted to ensure that the regulations were sufficiently strong before they were tabled: ‘The reason tobacco control regulations have not been tabled is because we are holding them’ (participant 13). To add to the apparent discord, an individual involved in the initial drafting of the regulations perceived that the KTCB was excluding some actors from the part of the process just prior to the submission of the regulations to parliament: ‘…I have no idea what the content of the tobacco control regulations (are that were) tabled in parliament’ (participant 5).

In contrast, informants from non-governmental organizations and intergovernmental organizations were divided on the issue of institutional coherence. Participant 13 who has interactions with the Board suggested that the MOH, the KTCB and civil society spoke ‘the same language’. However, participant 14 pointed out elements of internal challenges in KTCB’s operations stating: ‘Because of the challenge at times what I have seen is that they have not moved with the speed that it so desires and then I think it is administrative, leadership and resources’.

Our interviews brought to the surface some issues of (mis)trust between the different entities, which suggests that although the institutional structure facilitates coordination, the institutional culture remains a salient factor impacting the practice of coordination. Christensen and Lægreid (2008) note that ‘a central message is that structure is not enough to fulfil the goals of whole-of-government initiatives’. They further point out that a cultural–institutional perspective on coordination views ‘development of public organizations more as evolution than design, whereby every public organization eventually develops unique institutional or informal norms and values’ (Christensen and Lægreid 2008). From this perspective, the tension between the different bodies is in part a result of an adaptation to new ways of working. However, the recognition of the cultural component points to the need to foster relationships among the different bodies and to have a leadership that coordinates shared strategies and policy targets.

Four informants noted that one of the key challenges is the lack of a clear division of labor between the NCD division and the CPHO. Two informants suggested that the NCD division has more capacity, a larger network, and a history and understanding of tobacco control but plays a smaller role, while the CPHO, which has less experience with tobacco control is charged with managing the secretariat (Participants 13 and 17). These same informants argued that this tension in the health ministry partly contributed to the delay in developing tobacco control regulations to implement the TCA.

To address this tension between divisions, participant 14 suggests that much of the onus rests on the Director for Public Health who supervises both the NCD division and the CPHO. Most tobacco control policies and regulations go directly through this office and that of the principal secretary (PS). This finding suggests that key actors perceive a strong need to have high-level leadership that can bring together the different actors and create a culture of cooperation and systemic coordination (Vangen and Huxham 2003; Skelcher et al. 2005; O’Leary and Vij 2012; Nica 2013). Moreover, the informants’ observations reinforce findings from other health systems research that emphasizes leaders’ accountability in terms of both performance and for developing and maintaining political will to implement policy effectively (Brinkerhoff 2003). Similarly, a lack of goal setting for tobacco control, or at least unclear goals, appears to be a component of the weak institutional leadership. The present institutional context appears to rely on a more diffuse, decentralized leadership, where each division is working in parallel with limited overarching coordination (Francis et al. 2010). Furthermore, the limited measures to ensure the accountability of senior leaders’—for example through new regulations or through obligating some other clear and public articulation of the policy goals—appears to be perpetuating the slow pace of tobacco control policy reform. In other tobacco control contexts, successful efforts to increase leaders’ accountability have proven to be instrumental in pushing deeper policy reform (Francis et al. 2010)

Another related central institutional challenge concerns the role and authority of the KTCB. It is important to note that the TCA grants the KTCB advisory rather than decision-making capacity. The KTCB is structured to provide a platform for multi-sectoral and expert deliberation on tobacco control policy, with an aim of mainstreaming tobacco control in the government and public domain. While the TCA gives the cabinet secretary the authority to assign other duties to the Board related to enforcement, no minister has given the board such powers (participants 5 and 14). Participant 5 noted that they sensed that the KTCB wanted to act as an independent entity despite its mandated role as advisor to the ministry. As per the TCA, the MOH is given the discretion to incorporate the board’s recommendations and advice into its tobacco control activities. The informants observing this tension between the KTCB and the MOH characterized the board as enthusiastic to ‘act’ and implement the provisions of the Act. The efforts of the board were not presented as power-seeking but rather as enthusiasm that lead to overstepping the boundaries set forth in the Act, or at least perception thereof. Participant 17 expressed this dynamic in the following way:

Unfortunately the board is comprised of people who really want to go out (and implement measures), they have the energy to do the work. But when they are doing this work the technical officers in the ministry of health for tobacco control starts saying, ‘remember you are an advisory board why are you doing this and that’. That is where the conflict comes in and that is why I said the act itself needs amendment.

Participant 11 also alluded to this passion for action when he stated, ‘But I have also been told by people who know better, people who have been with us in this war. The day I was appointed the chairman of tobacco control board they told me you know, now you are the chairman of the board now you need to speak the language of the executives not to be activist. Then I told them you know with tobacco control once an activist, always an activist. You tone down you lost it, ok so some way somehow, we have been soldiering on’.

In general, the role of the KTCB remains unclear. At least five informants from both government and civil society noted that there was a genuine lack of consensus on both the mandate of the board. Participant 5 expressed that ‘…the KTCB’s mandate is to advise the ministry. They are operating like they have executive powers … which they don’t have’. Participant 11 also commented on the board’s role to advise the ministry, stating flatly that ‘… we have an act, a clause in the act that allows us to advise the minister…’. He also suggested that the cabinet secretary anticipated the kind of frank advice that it might receive from the KTCB:

….the (cabinet secretary for health) knew what kind of tactics they use (tobacco industry) when we came now to feed him with our own kind of advice (KTCB) that there is a problem, and fortunately he was like a convert right from the word go….

Much of the difference appears to be in the interpretation of what is meant by the board’s advisory role. In particular, informants observe that some permanent MOH staff believe that the KTCB has exercised executive powers and sought to occupy space that was not within their mandate. This tension has led to challenges between the MOH and the KTCB:

The Tobacco Control Board is an advisory board to the cabinet secretary for health. And because of that, … it has brought a little bit of friction between the ministry of health technical officials, not minister, technical officials and the board. Such that when the board wants to do ABCD this technical officer says you are just an advisory board. … But I know that the board is out and is doing, is doing a lot. (Participant 17)

Several informants expressed concern about the engagement of the KTCB with other bodies that could assist in enforcement of tobacco control. For example, officials from the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA), which has enforcement authority and is founded on issues surrounding substance abuse (including tobacco), indicated in key informant interviews that the KTCB is not directly working with them on these issues even though NACADA produces reports on tobacco use prevalence and other aspects of the harms of tobacco among youth, as well as other ongoing tobacco control-related research projects. According to participant 12 this research has not been requested and used by the KTCB.

I think what I will say is that the tobacco control board and NACADA, we have not been able to engage on a serious level. Maybe it something you can take up because I think it should be them that should be engaging us. Not the other way round because they are the lead agency in that area but we apart from the meetings that we usually have with the ministry and we are also member of the same board we have not been able to engage actively. (NACADA representatives)

Since the secretary to the KTCB is also a member of NACADA, better coordination could support NACADA operations since they have powers to enforce some key tobacco control laws in their mandate.

Consistent with our findings above around accountability issues specific to leaders’ performance and political will, 9 key informants explicitly identified challenges related to institutional resource constraints as a barrier to successful tobacco control policy implementation. Informants across the different institutions responsible for tobacco control uniformly noted the lack of resources, which suggests that the highest levels of leadership may not be making it a budgetary priority. Although resource constraints are a commonly identified barrier to policy implementation, tobacco control interventions such as graphic warning labels, smoke-free areas and marketing bans are seen as a public health ‘best buy’ due to the fact that they are inexpensive and highly cost-effective (Eriksen et al. 2015). However, resources are often an expression of political will and are necessary to generate momentum for policy change within government. Resources are also needed to facilitate coordination among different actors and monitor policy implementation.

First, the CPHO needs resources to fulfil its important mandate, but generally, funding for the secretariat has not been forthcoming from the government. It seems important for the CPHO, as the secretary to the KTCB, to demonstrate technical and strategic capacity because the secretariat must undertake requisite research, identify issues for consideration and initiate appropriate discussions among the key actors and to coordinate operations of the board. WHO needs assessment substantiates the recognition that funds are lacking noting that, despite being established in the CPHO’s office, the operations of the secretariat have been hampered by lack of funding (WHO 2012a). Similarly, participant 11 commented that,

They have not been funded I think that is an issue of the ministry of health. Because the technical person that is the PS of ministry of health should have sorted this out long time ago because it is a question of them having a vote line within the ministry’s budget

A similar lack of funding is evident with the KTCB. At least 9 informants noted the board does not receive the funds that it needs to execute the tasks with which it is charged. Participant 17 expressed this concern:

Yes, the board has not been really funded. I have heard that in this new financial year (2014/2015) I think they were trying to see if they can put something for the board. But officially no funding for the board from government. Yeah but I think they received some little support from elsewhere. Yeah but direct funding from government has been an issue. They even have a problem of office space, where should they be posted. I know, all those small frictions and because of that you find that enforcement of the act becomes an issue….

At least two civil society organizations corroborated the statement that they have provided operational funds to the KTCB (Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease). Participant 12 also explicitly noted the board’s budget woes:

But what I know is that—the board itself I think they are struggling with issues to do with budgeting. Because financially they did not get the budget to function.

Impacts of Kenya’s new constitution

During the time that officials were moving tobacco control regulations toward parliament, Kenya promulgated a new constitution in 2010 that created major structural–institutional changes, including the ways that the MOH operates. Previously both health policy and implementation were coordinated from the central government at the ministry headquarters. The new constitution has devolved health functions—particularly implementation of tobacco control policies and regulations—to 47 newly created county governments, each with their own governor and assembly that also pass sub-national laws and regulations (Barkan and Mutua 2010; McCollum et al. 2015). The fourth schedule of the constitution has decentralized some of the national government’s functions to the county level with the national government responsible for health policy broadly, while the county governments are now responsible for the control of drugs, ensuring participation of local communities in governance at a local level, advertising and, importantly, promotion of primary health care. This is unlike the previous regulatory system, in which implementation was coordinated centrally by the MOH. Moreover, county governments have their own budgets—i.e. not controlled by the central government—that assist in the implementation of health policies passed by the central government (Republic of Kenya 2010).

Many of the new structural changes stemming from the constitution—particularly the political decentralization—are likely to exacerbate the institutional challenges discussed above. The informants identified genuine concerns around tobacco control governance at the national level—including lack of coordination, accountability and clear goal-setting in the health sector—which have led to slow policy reform in tobacco control. But these challenges are likely to pile on top of similar and perhaps other distinct challenges at the county level.

Comprehensive tobacco control policy has always involved interaction between the different levels of government. Many of the pioneering policies, such as smoke-free public spaces, emerged at both municipal/county and national levels. For example, Asbridge (2004) highlights the fact that policy restricting smoking in public places in Canada was first developed using bylaws at the municipal level. This pattern of sub-national policy development prior to a consolidated federal approach is also reflected in the history of tobacco control in USA (Koh et al. 2007). However, the context where municipal policy preceded national policy was one in which tobacco control in general was quite novel and policymakers were experimenting with different measures. The contemporary context is one where there is robust evidence and now international law (i.e. FCTC) to support the implementation of a comprehensive slate of policy measures. In this context, municipal policy may lead to geographic fragmentation of policy within a country. This point is supported by our findings that suggest that the county governments have varied and mostly limited capacity to implement comprehensive tobacco control measures. Despite the potential for this devolution to lead to more tailored and localized measures targeted to address specific contexts (Christensen et al. 2014), there appears to be a greater immediate threat of fragmentation away from comprehensive tobacco control measures. Kaur and Jain (2011) highlighted similar challenges in coordinating implementation of national tobacco control laws at the district level in India. They found that as of the late 2000s only half of the districts had mechanisms to monitor the implementation of the national law. They attributed the challenges at the district level with a lack of material and human resources, and also a general lack of prioritization of tobacco control at this level (Kaur and Jain 2011).

The old constitutional structure created national-level institutions for tobacco control, including the secretariat for coordinating tobacco control activities (i.e. KTCB) in the office of the CPHO. These county governments now have a greater role in tobacco control and are developing new and independent institutions for tobacco control. Many county governments, however, have not yet placed priority on tobacco control efforts. According to 10 informants, there is enormous need to work with stakeholders to devise ways of downscaling tobacco control to the counties, in line with their mandate. This effort is complicated because there is enormous variation in the 47 counties on budgets and levels of development, and most have significant challenges in attracting qualified personnel to manage even basic operations. Another challenge is the fact that regulations have not been implemented for the TCA, leading to ambiguity in how the Act should be interpreted and implemented at the county level. This situation is not isolated to tobacco control. Funder and Marani (2015) studied how Environmental Officers navigated the implementation of the Environmental Act in one county in Kenya. One prominent finding was that these officers operated with broad ‘discretion and interpretation of the law … to find pragmatic solutions to the practical problem of limited budgets, time and operational scope’ in part because ‘few specific regulations exist and as the act itself is quite broad and of a cross-sectorial nature, its scope and practical implications is in many cases open to interpretation’ (Funder and Marani 2015). This context seems to mirror the institutional context of tobacco control. However, specific to the tobacco control context there seems to be a lack of awareness and corresponding misalignment between the national policy (and the FCTC) and the direction being taken in some of the counties. For example, the members of the county assemblies, who pass the county-level enforcement legislation, are not conversant with the WHO FCTC, the TCA or the regulatory requirements for tobacco control, an overall dynamic that presents serious difficulty for implementation. Participant 11 related an experience of visiting one of the major tobacco-growing areas because the governor, in direct violation of the WHO FCTC, was championing sub-national legislation to promote investment in tobacco leaf cultivation:

…I was in Migori with my board, going to see the governor of the Migori county who had been heard, had been seen, to be ready to champion the expansion of tobacco farming in Migori.

The transitional process to the new constitutional order has resulted in confusion, gaps and a lack of clarity in understanding the different specific roles of national versus county governments. It is important to note that the challenges facing Kenya exist across policy areas (Funder and Marani 2015; Cheeseman et al. 2016), and are similar in other countries (Brinkerhoff 1996). Christensen et al. (2014) analysed the challenges and strengths of Norway’s broad welfare administration reform of 2005 and found that coordination between the national and local level was the most challenging and one salient challenge was in terms of control and authority, a tension between the relative autonomy of localities and the need to adhere to overarching decisions made at the national level. In this case, prior to devolution, the national government had started restricting smoking zones, and prohibiting the sale of cigarettes to minors and in single sticks. The national government had also banned the promotion and advertisement of tobacco. But as county governments came into force, the enforcement and monitoring of these measures lagged as confusion and administrative conflicts over mandates predominated. When we asked a county-level informant (participant 10) who was charged with implementing the TCA, they noted that we ‘consult with the office of the CPHO on that question. We are not sure’ (country-level health official). In short, the national government expected the counties to take over, while the counties assumed that national governments would continue the enforcement.

Conclusion

Despite success in passing the Tobacco Control Act in Kenya, there remains a distinct lack of institutional coherence. One major component of this disjointed dynamic is the tension between the office of the CPHO and NCD division within the MOH. It is primarily the responsibility of the Director of Public Health to ensure that the two work together as the heads of both the CPHO and NCD division report to him. Similarly, the permanent secretary in the MOH should also take responsibility as the chief administrative officer and ensure coherence. It therefore calls for leadership in the health department. While Kenya has made progress in having the leadership of the mandated interagency committee situated in the health ministry, the national government must also ensure that there is coordination and coherence of tobacco control strategy and activities so as to ensure health objectives are met when dealing with other actors. These findings point to the need for a basic map of who is doing what at the federal and county levels and where gaps exist among action, expectation and mandate. It is important to note that very little attention has been paid in the tobacco control literature to internal coordination problems within the health sector. For example, a guide produced by the World Health Organization in 2004 on tobacco control legislation focused almost exclusively on protecting tobacco control measures from tobacco industry interference (Blanke and Costa e Silva 2004). This interference remains perhaps the most important challenge to successful comprehensive tobacco control legislation. However, the Kenya case suggests that governments must also attend to the institutional dynamics within the health sector to ensure successful governance.

The findings also suggest strongly that government tobacco control efforts struggle with what Christensen and Lægreid (2008) have termed horizontal and vertical internal coordination. Although horizontal challenges across sectors are perhaps a perennial challenge for tobacco control given the commitment of some economic sectors to support the tobacco industry, this study also highlights the importance of coordinating tobacco control between levels of government, particularly when new autonomy and mandates are granted to local authorities.

Governments are far from monolithic, with discrete agencies and actors who as a collective institution often have confusing or even contradictory mandates (Lencucha and Drope 2015; Lencucha et al. 2015a). It is therefore paramount that the agency tasked with steering tobacco control activities work with actors who share the same health objectives. This arrangement will help in the case of intractable conflict of perspectives and objectives with actors necessary in implementing a successful tobacco control programme in the country. Our findings point to ambiguity, if not on paper at least among the informants we interviewed, about the roles and responsibilities of different actors. Within Kenya, there seems to be a need to articulate the role of the KTCB and its relationship to the CPHO and the MOH. As it stands the KTCB does not fully exercise its potential power to implement tobacco control that it holds as stipulated under the Act, while members of the Board even may believe that they have roles that actually fall outside of the roles identified in the Act. Finding from Brazil supports the general point that national tobacco control advisory bodies struggle to find their place in the broader institutional landscape. In the case of Brazil, the national tobacco control commission (CONICQ) experienced challenges in both developing proposals and communicating these proposals to decision-makers (Bialous et al. 2014).

Though no panacea to institutional challenges, the findings in this research suggest that a clearer articulation of not just the institutional structure but also goals and accountability for reaching those goals are likely to help the health policy process. While sometimes actors emerge who push strong health policies effectively, these results reinforce the notion that clearly communicated rules and expectations can push governments toward action perhaps even where actors are not strong. A major lesson from this experience is that the ambiguity of roles has created a situation where many actors are not doing enough or perhaps are not empowered sufficiently to do what needs to be done to implement policies effectively.

Finally, there is an urgent need to review the working relationship among tobacco control actors and stakeholders under the new constitution. It is clear that researchers need to direct their gaze towards better understanding the barriers and facilitators to WHO FCTC implementation at the country level. There have been numerous calls to this effect specific to WHO FCTC implementation (e.g. Hammond and Assunta 2003) and more broadly to the implementation of international standards at the country level (Hoffman and Røttingen 2012; Frenk and Moon 2013; Hoffman et al. 2015). Our study highlights the additional need to emphasize the relationship between different offices within the MOH and levels of government when examining treaty implementation. It is this institutional emphasis that is often lacking in the research on tobacco control policy development and implementation. The government passed the TCA under the old constitutional order in which the system of governance was centralized. With the devolved system of governance, some functions that would have been comparatively easy for the MOH to coordinate are not clear or easy under the new structure. Currently, many county governments seem not to understand their role in tobacco control. The national government needs to increase the capacity of the sub-national governments on tobacco-related issues and then empower them to adequately play their constitutional role in the process. The shortage of both human and financial resources to implement functions like monitoring smoking in public places, marketing and sales to minors, as well as implementing education campaigns in schools, remains a grave challenge. If the government and its partners do not address these challenges soon, the important progress made in tobacco control in Kenya could stall.

In closing, these challenges are not confined to Kenya and as we mentioned above are not confined to tobacco control or even health policy but to environmental governance and other sectors. The WHO widely admits that other WHO FCTC Parties face similar struggles (WHO 2012b). The Kenyan experience offers useful lessons in the pitfalls of institutional incoherence, but more importantly, the enormous value in investing in and then promoting well-functioning institutions. This study points to the importance of coordinating policy development and implementation across levels of government and the need for leadership and clear mandates to guide coordination efforts.

Ethics Approval

IRB approval from McGill University, Morehouse University (American Cancer Society), Strathmore University Navigating Institutional Complexity within the Health Sector: Lessons from Tobacco Control in Kenya

Funding

This analysis is derived from research supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Fogarty International Center and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA035158. The research findings do not necessarily represent the views of the funder.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Asbridge M. 2004. Public place restrictions on smoking in Canada: assessing the role of the state, media, science and public health advocacy. Social Science & Medicine 58: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan J, Mutua M. 2010. Turning the Corner in Kenya. Foreign Affairs; https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/east-africa/2010-08-10/turning-corner-kenya [Google Scholar]

- Bialous S, da Costa e Silva V, Drope J, et al. 2014. The Political Economy of Tobacco Control: Public Health Policymaking in a Complex Environment. Rio de Janeiro: National Public Health School/FIOCRUZ and Atlanta: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki P, Waldorf D. 1981. Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Social Methods Research 10: 141–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blanke DD, e Silva VDC. 2004. Tools for Advancing Tobacco Control in the 21st Century: Tobacco Control Legislation: an Introductory Guide. Geneva: World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Boeije H. 2002. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity 36: 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff D. 2003. Accountability and Health Systems: Overview Framework and Strategies. Partners for Health Reform Plus. Washington DC: USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff DW. 1996. Coordination issues in policy implementation networks: an illustration from Madagascar’s environmental action plan. World Development 24: 1497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Cassels A. 1995. Health sector reform: key issues in less developed countries. Journal of International Development 7: 329–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Tobacco Control in Africa. 2013. Guide for Country Coordination Mechanism (CCM) for Tobacco Control. Kampala: Makwere University. [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman N, Lynch G, Willis J. 2016. Decentralisation in Kenya: the governance of governors. The Journal of Modern African Studies 54: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen T, Fimreite AL, Lægreid P. 2014. Joined-up government for welfare administration reform in Norway. Public Organization Review 14: 439–56. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen T, Lægreid P. 2008. The challenge of coordination in central government organizations: the Norwegian case. Public Organization Review 8: 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Costa e Silva VL, Pantani D, Andreis M, Sparks R, Pinsky I. 2013. Bridging the gap between science and public health: taking advantage of tobacco control experience in Brazil to inform policies to counter risk factors for non‐communicable diseases. Addiction 108: 1360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Alba LA. 2012. United Nations System-Wide Coherence on Tobacco Control. (Draft Resolution No. E/2012/L.18). New York, NY: United Nations Economic and Social Council, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Duit A, Galaz V. 2008. Governance and complexity—emerging issues for governance theory. Governance 21: 311–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N, Islami F, Drope J. 2015. The Tobacco Atlas, 5th edn. Atlanta: American Cancer Society and New York: World Lung Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Francis JA, Abramsohn EM, Park HY. 2010. Policy-driven tobacco control. Tobacco Control 19(Suppl 1): i16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J, Moon S. 2013. Governance challenges in global health. New England Journal of Medicine 368: 936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder M, Marani M. 2015. Local bureaucrats as bricoleurs. The everyday implementation practices of county environment officers in rural Kenya. International Journal of the Commons 9: 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, Mills A. 1995. Health sector reforms in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons of the last 10 years. Health Policy 32: 215–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, Raphaely N. 2008. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 1994–2007. Health Policy and Planning 23: 294–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer SL, Lillvis DF. 2014. Beyond leadership: political strategies for coordination in health policies. Health Policy 116: 12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond R, Assunta M. 2003. The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: promising start, uncertain future. Tobacco control 12(3): 241–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA. 2012. Assessing implementation mechanisms for an international agreement on research and development for health products. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90: 854–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SJ, Røttingen JA, Frenk J. 2015. Assessing proposals for new global health treaties: an analytic framework. American Journal of Public Health 105: 1523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isett KR. 2013. In and across bureaucracy: structural and administrative issues for the tobacco endgame. Tobacco Control 22(Suppl 1): i58–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J, Jain DC. 2011. Tobacco control policies in India: implementation and challenges. Indian Journal of Public Health 55: 220.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh D, Richards D. 2001. Departmentalism and joined-up government. Parliamentary Affairs 54: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Koh H, Joossens L, Connolly G. 2007. Making smoking history worldwide. New England Journal of Medicine 356: 1496–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencucha R, Drope J. 2015. Plain packaging: an opportunity for improved international policy coherence? Health Promotion International 30: 281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencucha R, Drope J, Chavez JJ. 2015a. Whole-of-government approaches to NCDs: the case of the Philippines Interagency Committee—Tobacco. Health Policy and Planning 30: 844–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencucha R, Drope J, Labonte R, Zulu R, Goma F. 2016. Investment Incentives and the Implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Evidence from Zambia. Tobacco Control 25: 483–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin M. 2007. When does cooperation improve public policy implementation? Policy Studies Journal 35: 629–52. [Google Scholar]

- McCollum R, Otiso L, Mireku M, et al. 2015. Exploring perceptions of community health policy in Kenya and identifying implications for policy change. Health Policy and Planning 31: 10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 358. [Google Scholar]

- Nica E. 2013. Organizational culture in the public sector. Economics, Management and Financial Markets 8: 179. [Google Scholar]

- Noy C. 2008. Sampling knowledge: the hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 11: 327–44. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary R, Vij N. 2012. Collaborative public management: where have we been and where are we going? The American Review of Public Administration 42: 507–22. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. 2007a. Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation – Kenya. (2007) Strategic Plan 2008–2012. Nairobi: Government Printer, Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. 2007b. Tobacco Control Act. Nairobi: Government Printer, Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. 2010. Schedule 4 of the Constitution of Kenya. Nairobi: Government Printer, Nairobi. [Google Scholar]

- Saloojee Y, Dagli E. 2000. Tobacco industry tactics for resisting public policy on health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78: 902–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelcher C, Mathur N, Smith M. 2005. The public governance of collaborative spaces: discourse, design and democracy. Public Administration 83: 573–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker G. 1998. Governance as theory: five propositions. International Social Science Journal 50: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Studlar DT. 2007. Ideas, institutions and diffusion: what explains tobacco control policy in Australia, Canada and New Zealand? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 45: 164–84. [Google Scholar]

- Studlar DT, Cairney P. 2014. Conceptualizing punctuated and non-punctuated policy change: tobacco control in comparative perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences 80: 513–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vangen S, Huxham C. 2003. Enacting leadership for collaborative advantage: dilemmas of ideology and pragmatism in the activities of partnership managers. British Journal of Management 14: S61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Gilson L. 1994. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning 9: 353–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2012a. Joint National Capacity Assessment for the Implementation of Effective Tobacco Control Policies in Kenya. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2012b. 2012 Global Progress Report on Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins P. 2002. Accountability and joined-up government. Australian Journal of Public Administration 61: 114–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Bai CX, Chen ZM, Wang C. 2015. Implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in China: an arduous and long‐term task. Cancer 121: 3061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yach D, Bettcher D. 2000. Globalisation of tobacco industry influence and new global responses. Tobacco Control 9: 206–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]