A field-based climate warming experiment reveals a loss of dynamical community stability due to altered species interactions.

Keywords: Climate change, community ecology, dynamical stability, experimental warming, temperature, species interactions, ants, forest

Abstract

How will ecological communities change in response to climate warming? Direct effects of temperature and indirect cascading effects of species interactions are already altering the structure of local communities, but the dynamics of community change are still poorly understood. We explore the cumulative effects of warming on the dynamics and turnover of forest ant communities that were warmed as part of a 5-year climate manipulation experiment at two sites in eastern North America. At the community level, warming consistently increased occupancy of nests and decreased extinction and nest abandonment. This consistency was largely driven by strong responses of a subset of thermophilic species at each site. As colonies of thermophilic species persisted in nests for longer periods of time under warmer temperatures, turnover was diminished, and species interactions were likely altered. We found that dynamical (Lyapunov) community stability decreased with warming both within and between sites. These results refute null expectations of simple temperature-driven increases in the activity and movement of thermophilic ectotherms. The reduction in stability under warming contrasts with the findings of previous studies that suggest resilience of species interactions to experimental and natural warming. In the face of warmer, no-analog climates, communities of the future may become increasingly fragile and unstable.

INTRODUCTION

Climate-driven shifts in community structure and function are already apparent in natural systems (1). Identifying the mechanisms that underlie these shifts in communities in response to climate change is vital to ecological forecasting efforts (2, 3). No species is an island, but many models of species responses to climate change make this assumption, ignoring indirect effects of climate change on species interactions. State-of-the-art forecasting models describe future communities at an equilibrium state determined by the joint effects of climate and species interactions (4, 5). However, this equilibrium perspective overlooks the dynamics of colonization, extinction, and patch occupancy of communities as they experience climate change. The outcomes of species interactions and community dynamics can allow us to forecast community resilience or decline under environmental perturbation, but only a limited number of statistical and theoretical models have addressed this question of system dynamics and stability under climate change (6–8). We still lack an understanding of how these processes operate in nature.

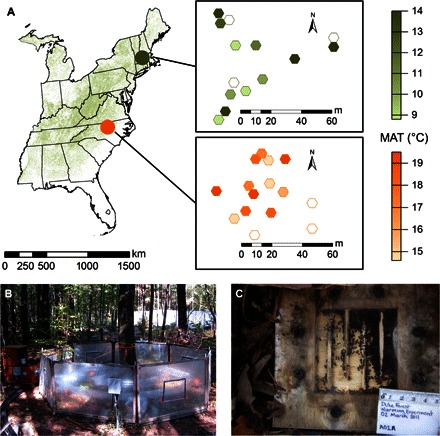

We explored the temporal dynamics and mathematical stability of the responses of ant communities to climate warming in one of the largest, geographically replicated experimental warming arrays in the world (9). The arrays were established in a warm, southern site (Duke Forest, located in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, USA) and a cool, northern site (Harvard Forest, located in the New England upland region of Massachusetts, USA). These sites are located, respectively, near the center and the northern range boundary of the deciduous forest biome in eastern North America. The experimental arrays spanned 6.5 degrees of latitude, yielding a mean annual temperature (MAT) difference of 5.8°C (Fig. 1A). Each site contained 15 open-top chambers, each 5 m in diameter, and warmed the forest floor year-round with thermostat-controlled forced air passed over hydronic heaters.

Fig. 1. Experimental chambers warm the forest floor inhabited by ants in nest boxes.

(A) Geographic position of warming arrays at Duke Forest (orange) and Harvard Forest (green) toward the center and northern boundary of temperate deciduous forest (45) and the local spatial arrangement of the chambers at each site. Color intensity indicates greater MAT, with chamberless control plots indicated by unshaded symbols. (B) A single warming chamber at Duke Forest. Note that the diameter of each chamber is roughly 1000 ant body lengths. (C) Nest box containing a Crematogaster lineolata colony, with the cover tile removed.

At each site, nine chambers were warmed in increments of 0.5°C from 1.5° to 5.5°C above ambient temperature; three additional chambers had forced air, but no heat, and a final three chamberless controls had no forced air and no heat (Fig. 1, A and B). The open-top chambers were also open at the bottom to allow free access to ants and other invertebrates. The range of temperatures spanned by the warming treatments encompasses climate projections of increased MAT from 1° to greater than 5°C over the next century (10). The warming increments represent a continuous experimental gradient of increasing temperature between sites: The unheated control chambers at the southern Duke Forest site had similar temperatures to the warmest heated chambers at the northern Harvard Forest site.

During the 5-year study, more than 60 species of ground-foraging ants were collected in the chambers, 30 of which occurred at both sites. Because most of these species forage a distance of less than 1 m from their nesting sites (11), the responses of ants to climate warming in these 5-m-diameter chambers primarily reflect the activities of resident colonies within the chambers, rather than transient movements of foragers or queens nesting outside of the chambers. More than 98% of foraging activity observed in the chambers involved workers originating from nests within the chambers (11). For ant foragers, with a typical body length of ~0.5 cm, the equivalent area of each chamber scales up to ~314 ha (1.2 square miles) in terms of human body lengths.

At the start of the experiment in 2010, we placed four artificial nest boxes into each of the 30 chambers; midway through the experiment, we added another four nest boxes. Because many ant species in eastern deciduous forests are nest-site limited, and competition for nest sites can be intense (12), artificial nest boxes are ideal experimental units for exploring the impacts of climate on interactions and associations among species. The boxes were constructed from carved wood blocks and were fitted with clear Plexiglas viewing windows that allowed us to census colonies with minimal disturbance (Fig. 1C). Censuses occurred approximately monthly during the growing season at each site over a span of 5 years of experimental warming (fig. S1 and table S1).

For the four or five most common species at each site (see Materials and Methods for species selection criteria), we pooled nest box census records within each chamber and estimated the species-specific monthly binomial probability of colonization, extinction, and occupancy. Colonization and extinction were defined operationally as appearances and disappearances between consecutive censuses of a species in a nest box. Nest box occupancy per chamber ranged from 0.10 to 0.33 at Duke Forest and from 0.07 to 0.22 at Harvard Forest, with considerable dynamic turnover between consecutive monthly censuses and frequent replacement of one species by another with no intervening vacancy (table S1). Multiple occupancy of nest boxes was never observed: At each census, nest boxes were either occupied by a single colony or empty. These data suggest that nest boxes provided adequate nesting sites but were still sufficiently limited to reflect the dynamics of interactions and associations among species. Note that periodic nest box censuses provide indirect evidence of interactions among species through shifts in nest box usage as opposed to direct observations of interactions. Here and elsewhere, we refer to altered species interactions under climate change in a general sense, but because we acknowledge the possibility (albeit one that we consider unlikely) that some or all of the shifts in nest box usage in our experiment may be simple associations among species absent any interactions, we refer to the results from our experiment as shifts in species associations (see Results and Discussion for a full discussion of the nature of species interactions and associations in our system).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

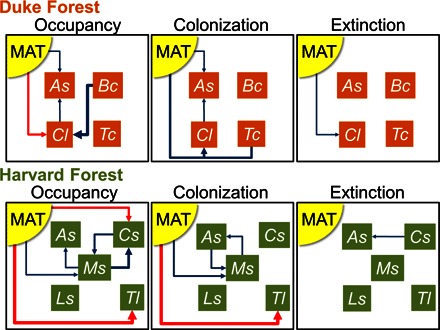

We used multiple regression models with a quasi-binomial error structure [generalized linear models (GLMs)] to tease apart the effects of MAT in each chamber and the presence of other species on responses to warming. There were few cases in which colonization, occupancy, or extinction was affected by only MAT, as is often assumed for many species distribution models. Instead, the responses of species depended on both temperature and other species. Most species were connected to one or two other species in simple networks of positive and negative associations mediated by temperature (Fig. 2 and table S2). The responses of individual species to warming and to the presence of other species were complex and idiosyncratic, and these responses were different for colonization, extinction, and occupancy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Direct and indirect effects of warming on ant communities.

Path diagram indicating the magnitude (arrow width, scaled for each model term separately; the one interaction term was arbitrarily given an intermediate arrow width) and direction (blue, negative; red, positive) of the effects of MAT and the presence of other ant species on the occupancy, colonization, and extinction of ant species inhabiting artificial nest boxes at the Duke Forest and Harvard Forest warming arrays (statistical summaries are given in table S2). Interaction effects between MAT and species presence are indicated by lines connecting MAT with species and terminating in a single arrow. Only statistically significant (P < 0.05) effects are shown. Species codes: As, Aphaenogaster spp.; Bc, B. chinensis; Cl, C. lineolata; Cs, Camponotus spp.; Ls, Lasius spp.; Ms, Myrmica spp.; Tc, T. curvispinosus; Tl, T. longispinosus.

Individual species responses to warming at Duke Forest

At Duke Forest, C. lineolata and, to a lesser degree, Aphaenogaster spp. were the most strongly influenced by the direct effects of warming. With increasing warming, the probability of nest box occupancy by C. lineolata significantly increased and the probability of extinction decreased (figs. S2 to S4 and table S3). Aphaenogaster spp. exhibited decreased occupancy and colonization with increasing temperature (figs. S2 and S3 and table S3). For the remaining two focal species, Brachyponera chinensis and Temnothorax curvispinosus, occupancy, colonization, and extinction did not respond significantly to increasing chamber temperature. We found some cases in which occupancy of a focal species responded to temperature or other species, but we did not detect effects on colonization or extinction, possibly because of limited sample sizes (figs. S3 and S4 and table S3).

Although there is good evidence for the direct effects of temperature on C. lineolata and Aphaenogaster spp., there were also indirect effects of temperature on nest box occupancy, colonization, and extinction that were mediated by its effects on co-occurring species (Fig. 2 and table S2). For example, the presence of C. lineolata was negatively associated with Aphaenogaster spp. occupancy and colonization; the presence of B. chinensis (a newly arrived exotic species at Duke Forest) was negatively associated with C. lineolata occupancy, and there was a significant interaction of MAT and T. curvispinosus occupancy on C. lineolata colonization.

Individual species responses to warming at Harvard Forest

At Harvard Forest, Camponotus spp., Myrmica spp., and Temnothorax longispinosus were the most strongly influenced by the direct effects of warming. Nest box occupancy and colonization of Myrmica spp. decreased with warming (figs. S5 and S6 and table S4), whereas occupancy by Camponotus spp. and T. longispinosus (fig. S5 and table S4) and colonization by T. longispinosus (fig. S6 and table S4) increased with warming. Aphaenogaster spp. and Lasius spp. did not exhibit significant occupancy or colonization responses to increasing chamber temperature. None of the five focal species exhibited significant effects of warming on the probability of extinction (fig. S7 and table S4).

We again found the widespread importance of the indirect effects of other species on occupancy, colonization, and extinction at Harvard Forest (Fig. 2 and table S2). Aphaenogaster spp. and Myrmica spp. were each negatively associated with the other’s colonization, and Myrmica spp. and Camponotus spp. were each negatively associated with the other’s occupancy. The presence of Camponotus spp. and Myrmica spp. was negatively associated with Aphaenogaster spp. extinction and occupancy, respectively.

Community responses to warming at Duke and Harvard forests

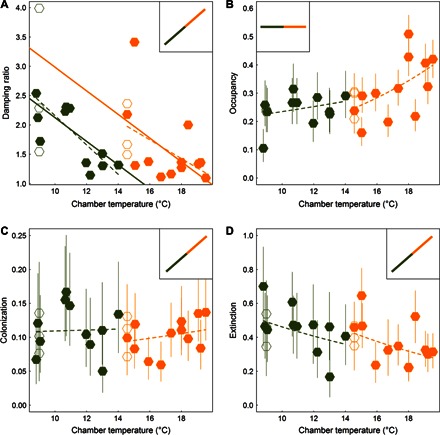

In contrast to the idiosyncratic responses of individual species, responses at the community level were more consistent: Within and between sites, warming increased occupancy and decreased extinction, with nonsignificant, but positive, effects on colonization (Fig. 3 and Table 1). There was no evidence that MAT influenced occupancy, colonization, or extinction differently between sites (no significant site × temperature interactions; table S5). When the sites were analyzed separately, occupancy increased and extinction decreased with temperature at Duke Forest. At Harvard Forest, the effects were marginally nonsignificant, but the slopes were of the same magnitude and direction as at Duke Forest (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Stability and demographic responses of ant communities to warming.

(A) Damping ratio, (B) occupancy, (C) colonization, and (D) extinction as functions of MAT (°C) for ant communities inhabiting nest boxes at Duke Forest (orange) and Harvard Forest (green); chambered plots are represented by filled symbols, and chamberless control plots are represented by open symbols. For the damping ratio, dashed lines represent simple linear regressions; the solid lines are from an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with separate intercepts for site and a common slope for MAT (Table 1). For occupancy, colonization, and extinction, mean proportions and binomial 95% confidence intervals are presented; dashed lines are predicted values from quasi-binomial GLMs (Table 1). Inset panels depict the null expectations for stability, occupancy, colonization, and extinction under a simple model of increasing activity of thermophilic ectotherms at higher temperatures.

Table 1. Occupancy, colonization, extinction, and stability responses to warming.

For occupancy, colonization, and extinction, slope estimates ± 1 SE are from GLMs using a quasi-binomial error structure to examine the effect of MAT on community-wide occupancy, colonization, and extinction. F ratios and P values indicate the statistical significance of chamber temperature or site. The pseudo-r2 is calculated as 1 − (residual deviance / null deviance). For stability, slope estimates ± 1 SE are from simple linear regressions to examine the effect of MAT on stability (damping ratio) for each site considered separately and from an ANCOVA with separate intercepts for site and a common slope for MAT (the site × MAT interaction was not significant and was dropped from the final model).

| Data subset | Response | Predictor | Estimate | SE | F | P | r2 |

| Duke Forest | Occupancy | MAT | 0.0965 | 0.0299 | 10.5 | 0.00156 | 0.0721 |

| Colonization | MAT | 0.0338 | 0.0422 | 0.64 | 0.425 | 0.00552 | |

| Extinction | MAT | −0.0834 | 0.03 | 7.75 | 0.00634 | 0.0678 | |

| Harvard Forest | Occupancy | MAT | 0.0362 | 0.0356 | 1.03 | 0.313 | 0.00815 |

| Colonization | MAT | 0.00626 | 0.0375 | 0.0278 | 0.868 | 0.000221 | |

| Extinction | MAT | −0.0627 | 0.0364 | 3 | 0.0868 | 0.026 | |

| Duke Forest | Stability | MAT | −0.16 | 0.0793 | 4.057 | 0.0651 | 0.238 |

| Harvard Forest | Stability | MAT | −0.25 | 0.0921 | 7.38 | 0.0187 | 0.381 |

| Both sites (common slope model) | Stability | MAT | −0.201 | 0.0598 | 11.3 | 0.00237 | 0.347 |

| Site | −0.861 | 0.418 | 4.25 | 0.0494 |

Community-level responses were driven by a few thermophilic species at each site that increased in occupancy and colonization in response to warming: Camponotus spp. and T. longispinosus at Harvard Forest and C. lineolata at Duke Forest. Camponotus spp., C. lineolata, and T. longispinosus have upper thermal tolerances between 42° and 46°C, compared to upper thermal tolerances of 38° to 43°C for the rest of the community (13). Because individual species responses were predictable on the basis of their upper thermal tolerances, community-level responses to warming were consistent.

Community stability under warming

To explicitly model the associations among species and link the outcomes of these associations to warming, we constructed a Markov transition matrix model (14, 15) for the data from each individual chamber. For a community of n interacting species, we constructed an (n + 1) × (n + 1) transition matrix, which includes a state for each species and one state for an empty patch. We recorded a total of 6960 individual state transitions in the 240 nest boxes and used these to construct 30 independent transition matrices, one for each chamber in the experimental array. The transition matrix describes the discrete-time dynamic occupancy of a patch based on the colonization, persistence, extinction, and turnover of individual species and their responses to each other. The model preserves the identity of each species and allows for asymmetries in the strength and outcome of species associations at each of the different chamber temperatures.

The left eigenvector of the transition matrix represents the vector of relative abundances of species at equilibrium, and the damping ratio of the first two eigenvalues represents the Lyapunov stability and measures return time to equilibrium following a small perturbation (16). Our parameterization of the Markov model does not assume that communities have reached an equilibrium state, but we do assume that transition probabilities for each chamber, averaged over the entire collecting period, were drawn from a stationary distribution.

These Markov models predicted a consistent shift in equilibrium species composition through time, with a set of thermophilic “winner” species becoming more common and an approximately equal number of “loser” species becoming less common. At Duke Forest, the equilibrium frequency of the thermophilic C. lineolata increased with warming, whereas the equilibrium frequencies of Aphaenogaster spp., T. curvispinosus, and empty patches either decreased or exhibited little change (fig. S8 and table S6). These shifts reflect the change in transition probabilities in the individual matrices: The transition (empty→C. lineolata) increased at higher temperatures, whereas the transitions (C. lineolata→Aphaenogaster spp.) and (C. lineolata→T. curvispinosus) decreased at higher temperatures. At Harvard Forest, there was a nonsignificant trend at higher temperatures toward a greater equilibrium frequency of the relatively thermophilic T. longispinosus (fig. S9 and table S6). Individual transition probabilities as functions of chamber temperature supported this result: The transition (T. longispinosus→empty) trended negatively with increased warming (table S7). Analyses of individual transition probabilities reinforced the results of the species association GLMs (Fig. 2), which revealed evidence of indirect effects of warming at Harvard Forest. Although the transition (Myrmica spp.→Myrmica spp.) significantly increased with warming, there was also an increase in the transition (Myrmica spp.→T. longispinosus) with warming. The change in species associations with increasing temperature was further reflected in a decrease in the transitions (Aphaenogaster spp.→Myrmica spp.) and (Myrmica spp.→Aphaenogaster spp.) with warming.

The net effect of these altered species associations was the consistent reduction in the damping ratio of the transition matrix under warmer temperatures (Fig. 3A). This ratio measures the relative speed at which a perturbed system returns to its equilibrium (Lyapunov stability). Collectively, MAT and additive effects of site accounted for 35% of the variation among chambers in the damping ratio (Table 1). Thus, as temperatures increased, community stability decreased and did so at both sites. The stability and occupancy patterns predicted by the Markov models were not affected by using different criteria for including species in the model or by incorporating the possibility of measurement error in the estimation of transition probabilities (see “Alternative demographic and transition matrix model specifications” in the Supplementary Materials).

To understand the mechanisms that disrupt community stability with warming, we analyzed the relationship between the Lyapunov stability of a matrix and its individual transition elements. Although the Lyapunov exponent reflects nonadditive contributions of all the transition elements in the matrix (16), the best correlate of the Lyapunov stability is the sum of the diagonal transition elements, which measures the probability that the system remains unchanged from one time step to the next (resistance). The higher the probability of species persistence from one time period to the next, the lower the Lyapunov stability (table S8). At the southern site and in warm chambers, persistence of colonies was high, community resilience was low, and the return to equilibrium was slow. In contrast, at the northern site and in cool chambers, persistence of colonies was low, assemblage resilience was high, and the return to equilibrium was fast. When not perturbed, the system exists in a state of dynamic turnover; however, when perturbed by increasing environmental temperature, thermophilic colonies remain in nest sites for longer periods of time, reducing the overall stability of the community. Our metric of stability, the damping ratio, was uncorrelated with sample size, both including and excluding the empty class. Therefore, results for the damping ratio were driven by the structure of the matrices themselves rather than by variation in sample sizes used to construct the transition matrices in different chambers.

Null expectations for temperature effects on communities

Understanding the responses of ectotherms to climate change is especially challenging because of feedback between organismal physiology and behavior. Because the behavior and activity of ectotherms strongly depend on ambient temperature (17, 18), standard sampling procedures, such as pitfall traps may passively accumulate more individuals, even if the only effect of elevated temperatures is the increased random movement of foragers (19). For example, at the Duke Forest site, foraging activity by ant workers closely tracks seasonal and diurnal fluctuations in temperature (11, 20). However, the dynamics of nest site occupancy by colonies refute this null hypothesis of simple temperature-driven activity levels. At higher temperatures, nest occupancy increases (Fig. 3B) because of a strong reduction in nest site abandonment (Fig. 3D). These results were qualitatively robust to several variations on the formulation of the Markov model, such as treating net boxes as unavailable for colonization when occupied by a nonfocal species, changing the number of focal species used for the analysis, and replacing estimated transition probabilities of 0.0 with small nonzero probabilities reflecting measurement error (see “Alternative demographic and transition matrix model specifications” in the Supplementary Materials).

Limitations of our approach and priorities for future research

Our field-based manipulation of environmental temperature yielded evidence consistent with altered species associations among forest ant species and a reduction of dynamical stability at the community level. However, there are some limitations of our current study that future research efforts could address. Here, we highlight three such areas for further development. First, although we were able to quantify the consequences of warming with respect to ant community stability, we did not directly observe interactions among species leading to nest displacement. Given the strong nest site limitation in forest ants (21) and our direct observations of competitive interactions among ant species in and near the warming chambers (22), altered species interactions seem the most likely explanation for our results. An alternative explanation for our results is possible, though one that we consider unlikely given the above: Our models may simply be detecting associations among species, absent any interactions, in their responses to warming. Detailed assessments of the nature and magnitude of altered species interactions under climate change are clearly needed—a call that has now been echoed by many climate researchers [reviewed by Angert et al. (23)]. Irrespective of the distinction between species interactions and associations, the outcomes of the 5-year climate manipulation experiment are clear: Warming alters species-specific occupancy, colonization, and extinction rates; shifts the outcomes of pairwise associations among species; and consistently decreases the overall stability of temperate forest ant communities at two widely separated sites in eastern North America.

Second, our warming chambers, although being some of the largest of their kind, are limited to inferences at the chamber scale. However, given the small size of ants relative to the 5-m diameter of the warming chambers, entire ant communities are encapsulated within the footprint of a single chamber (see Materials and Methods). Because our study identifies a pattern of reduced stability under warming and suggests a mechanism via altered species interactions, then all else being equal, we would expect the pattern and process to scale up, that is, that the altered species interactions and dynamics of ant community responses to warming at the chamber scale would reflect responses at broader spatial scales of entire forests. Yet, it is still possible that our chamber-level results for dynamical stability may not scale up beyond the chamber or site level to the regional level. A regional scale or larger test of shifts in dynamical community stability under experimental climate change does not seem feasible with the infrastructure needed for a manipulative warming experiment. Testing whether our chamber results extend to larger spatial scales could be possible using space-for-time substitution (24). Indeed, this approach would allow for tests of dynamical stability from cooler and warmer background climates—an especially relevant comparison because temperate and tropical communities may respond differently to increasing temperature (25). However, as many researchers have noted, inferences from warmer geographic locations can, but do not necessarily, reflect responses to warming per se [reviewed by Bellard et al. (26)]. In this regard, it is interesting that both our higher and lower latitude warming arrays, situated at 42.5°N and 36°N latitude, respectively, yielded similar results, with cooler and warmer forest ant communities each showing a reduction in community stability under experimental warming. Many studies point to the greater susceptibility of lower-latitude (especially tropical) habitats to climate change, though some models and empirical work suggest greater susceptibility at mid- and higher latitudes (27, 28). Broader taxonomic and spatial coverage of community stability is needed to understand the biogeographic patterns of community stability and responses to global temperature rise.

Third and finally, although the reduction in community stability under warming translates to longer return times to equilibrium following an environmental perturbation, such as a marked increase in temperature, the long-term biological significance of a reduction in dynamical community stability is unclear. With slower recovery times following perturbation, warmed communities may be more fragile and susceptible to extirpation with increasing temperature (29). An important next step for this work then is to link the reduction in stability with the demographic and fitness consequences for individual species and biodiversity at the community level. Indeed, our analyses of the abundances of individual ant species and community composition in the warming arrays are already suggestive of potential higher-level consequences of the loss of dynamical stability. Within the warming chamber arrays, we detected substantial shifts in individual ant species abundances (13) and modest, but significant, shifts in ant community composition with increasing chamber temperature (20); these shifts tended to favor thermophilic subsets of communities, in some cases at the expense of less heat-tolerant species (see Supplementary Materials for a more detailed discussion of community dynamics and compositional changes).

Consequences of altered species interactions in a warmer world

What will communities of the future look like in a warmer world? Before species migrate from distant latitudes in an effort to track a changing climate (30), there will be shifts in abundance among resident species. It is this shift in abundance that is forecast with the Markov transition models of nest box dynamics. Although there is a strong focus in the literature on forecasting patterns of biodiversity change with warming (31), the effects of climate change on community dynamics are not well understood. Here, we provided experimental evidence for the cascading effects of warming on individual species and community-wide colonization and extinction processes, species associations, and, ultimately, community stability. Many researchers have pointed to the difficulty of incorporating species interactions into models of responses to climate change (32, 33). The idiosyncratic effects of climate and other species on colonization, extinction, and occupancy rates of individual ant species (Fig. 2) certainly do not lend themselves to simple generalizations. Nevertheless, at the community level, there were consistent increases in occupancy and decreases in extinction (Fig. 3). The dominance of thermophilic species increased in warmer experimental chambers, and this reduced the stability of local ant communities across climatically diverse sites.

Although the loss of community stability under warming may seem an intuitive result, decreasing stability is surprising for at least two reasons. First, decreasing stability of intact communities provides an important alternative to widely anticipated scenarios of “regime shifts” under climate change, in which communities switch abruptly to a contrasting alternative stable state (34). Second, some previous studies have found evidence for resilience, not destabilization, of trophic, predator-prey, and competition-based species interactions in response to climate change over geological (35, 36) and contemporary (6, 37, 38) time scales. However, these studies have relied on theoretical models, correlative data, and nondynamical community stability approaches. In contrast, our direct measurements of extinction and colonization dynamics in a long-term controlled field experiment suggest that climate warming not only may change the composition of ecological communities but also may lead to greater instability and slower recovery from environmental perturbation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Warming chambers

We constructed two experimental warming arrays at the center and the northern range boundary of the temperate deciduous forest biome in the eastern United States. The higher latitude array was located within Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts, and the lower latitude array was located within Duke Forest, Hillsborough, North Carolina. Details of the chamber construction and operation are provided elsewhere (9), but briefly, each site contained 15 chambers (5 m in diameter) that warmed the forest floor. Nine of these chambers were warmed via forced air in a regression design from 1.5° to 5.5°C above ambient in increments of 0.5°C; three additional chambers had forced air, but under ambient conditions, and a final three chambers had no forced air (“chamberless control”) and remained under ambient conditions.

We computed the MAT for each of the chambers with forced air (12 per site). The MAT of the chamberless control plots was computed for the single set of sensors located outside the warming chambers, and this value was assigned as the MAT for all three chamberless control plots. Raw temperature data were recorded at hourly intervals via a ground-based sensor network of thermistors in the chambers; MAT is the mean of all hourly temperatures for the years in which the nest box censuses occurred.

Censuses of nest boxes

We constructed nest boxes from a wood block of untreated pine (14 cm × 15 cm × 2 cm) and balsa wood; we routed a zigzag pattern into the top of the nest box and cut an entryway in the side of the box. The nest box was covered on top with Plexiglas and a ceramic tile. The tiles were lifted to census the ant colony visible through the Plexiglas top.

An initial group of four nest boxes (A to D) per chamber was deployed at the beginning of the warming experiment, representing census points 1 to 41 at Duke Forest and census points 1 to 19 at Harvard Forest. A second group of four nest boxes (E to H) per chamber was deployed midway through the warming experiment, representing census points 26 to 41 at Duke Forest and census points 8 to 19 at Harvard Forest.

The nest boxes were censused approximately monthly during the growing season at Duke and Harvard forests (fig. S1). Note that fewer censuses occurred at Harvard Forest because the snow-free growing season is much shorter there than at Duke Forest. The number of days between censuses at Duke Forest ranged from 12 to 154, with a mean of 38.7 and an SD of 23.9. The first census occurred on 7 February 2011, and the last census occurred on 19 May 2015. The number of days between censuses at Harvard Forest ranged from 16 to 314, with a mean of 63.2 and an SD of 71.2. The first census occurred on 31 May 2012, and the last census occurred on 14 July 2015.

Species

Collectively, the two sites harbor 60 species of ground-foraging ants, with more than 30 species common to both sites. Ants make up more than half of macroinvertebrate abundance in eastern forests in North America, where they perform vital functions in ecosystems (39). Although some ant species in eastern U.S. forests frequently relocate nests (12), most species in this system foraged and dispersed over distances of less than 1 m (13). The foragers of resident colonies almost never ventured outside the chamber, and resident colonies usually remained within experimental chambers between consecutive censuses.

At Duke Forest, we found a total of 10 species (or species groups) inside the nest boxes: Stigmatomma pallipes (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), Aphaenogaster lamellidens (10 occurrences; 5 chambers), Aphaenogaster spp. (Aphaenogaster rudis and Aphaenogaster carolinensis) (444 occurrences; 15 chambers), B. chinensis (8 occurrences; 2 chambers), Camponotus castaneus (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), C. lineolata (466 occurrences; 15 chambers), Nylanderia flavipes (2 occurrences; 2 chambers), Prenolepis imparis (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), Strumigenys spp. (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), and T. curvispinosus (79 occurrences; 9 chambers). From this group, we identified four focal species (or species groups) with sufficient replication for analysis and for which we are reasonably confident of their moving the entire colony into the nest box rather than their temporarily occupying the nest box as transient foragers: Aphaenogaster spp. (A. lamellidens combined with Aphaenogaster spp.; 454 occurrences; 15 chambers), B. chinensis (8 occurrences; 2 chambers), C. lineolata (466 occurrences; 15 chambers), and T. curvispinosus (79 occurrences; 9 chambers).

At Harvard Forest, we found a total of 14 species (or species groups) inside the nest boxes: Aphaenogaster picea (62 occurrences; 15 chambers), Aphaenogaster fulva (9 occurrences; 7 chambers), Aphaenogaster spp. (92 occurrences; 15 chambers), Camponotus nearcticus (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), Camponotus novaeboracensis (13 occurrences; 3 chambers), Camponotus pennsylvanicus (46 occurrences; 5 chambers), Formica spp. (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), Lasius alienus (8 occurrences; 4 chambers), Lasius nearcticus (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), Lasius sp. (1 occurrence; 1 chamber), Myrmica punctiventris (21 occurrences; 11 chambers), Myrmica spp. (151 occurrences; 12 chambers), Tapinoma sessile (2 occurrences; 2 chambers), and T. longispinosus (25 occurrences; 6 chambers). From this group, we identified five focal species (or species groups) with sufficient replication for analysis and for which we are reasonably confident of their moving the entire colony into the nest box rather than their temporarily occupying the nest box as transient foragers: Aphaenogaster spp. (A. picea, A. rudis, and Aphaenogaster spp. combined; 163 occurrences; 15 chambers), Camponotus spp. (C. pennsylvanicus, C. nearcticus, and C. novaeboracensis combined; 60 occurrences; 7 chambers), Lasius spp. (L. alienus, L. nearcticus, and Lasius spp. combined; 10 occurrences; 5 chambers), Myrmica spp. (M. punctiventris and Myrmica spp. combined; 172 occurrences; 12 chambers), and T. longispinosus (25 occurrences; 6 chambers).

The ant species that we used to model the direct and indirect effects of climatic warming are a relatively small subset of the ant species present at each site and represent abundant ant species that typically nest in logs or small cavities and were thus amenable to living in nest boxes. Ant species with other nesting strategies (for example, soil nesting or arboreal nesting) and rare ant species were either too difficult to monitor or too data-poor for us to model their responses to warming. We note that although our chambers effectively contained entire ant communities, because nest box sampling plus alternative sampling methods, that is, pitfall trapping and litter sifting (9), yielded species diversity estimates on the order of regional levels of ant biodiversity (20), we focused our analyses on a subset of nest box–inhabiting species for practical reasons surrounding assessment and modeling.

Chamber 5 at Harvard Forest (a target warming increase of +5°C above ambient, with a MAT of 13.8°C) was too sparsely populated to estimate transition probabilities for our Markov model; thus, we eliminated chamber 5 from the Markov model and all other analyses. Chambers 3 and 10 at Harvard Forest (target warming increases of +2° and +4.5°C above ambient with MATs of 10.7° and 13.0°C, respectively) had estimated equilibrium frequencies of 1 for Camponotus spp.; thus, we added counts of 1 to the Camponotus transition matrix to allow for a small transition probability to the other states. Our results were qualitatively similar when we removed Camponotus entirely from these matrices or excluded chambers 3 and 10 from our analyses. For both sites, we used the criterion that a species (or species) group must be present during greater than one census point in at least two chambers to be included in the analyses.

Demographic response variables

We calculated proportions for the following: occupancy, as the number of times the focal species was present out of the total number of times the nest box was censused; colonization, as the number of times the nest box shifted from another state to the focal species out of the total number of times the species was present; extinction, as the number of times the nest box shifted from the focal species to another state out of the total number of times the species was present; and persistence, as the number of times the nest box contained the focal species and persisted with the focal species to the next census point.

We compared our results for occupancy calculated as the number of times the focal species was present out of the total number of times the nest box was censused to occupancy estimated from colonization and extinction probabilities as the equilibrium frequency in the island-mainland variation of Levins’ (40) metapopulation model

We further used colonization and extinction probabilities to estimate turnover

Statistical analysis

All statistical models were performed using R version 3.2.2, Fire Safety (41). For each of the focal species at each site, we fit models of the proportion of nest boxes that were occupied, those that were colonized, and those that went extinct as functions of chamber MAT. Owing to issues with dispersion not equal to 1, we used GLMs with a quasi-binomial error structure. We conducted similar quasi-binomial GLMs for community-wide occupancy, colonization, and extinction at Duke Forest and Harvard Forest separately. We also fit models of the proportion of nest boxes that were inhabited by the focal species in one census point and persisted to the next census point. Like the occupancy, colonization, and extinction models, we used quasi-binomial GLMs to examine the impact of MAT of the chambers on persistence. We used F tests to assess the statistical significance of chamber temperature, because these tests are most appropriate for models where dispersion is estimated by moments (42).

We explored the effects of nonfocal species presence or absence over the course of the census period on each of the focal species responses (occupancy, colonization, and extinction) at each site. For each focal species and response variable, we constructed four models: (i) a main effect of chamber MAT, (ii) a main effect of nonfocal species presence or absence, (iii) both main effects of MAT and nonfocal species presence or absence, and (iv) both main effects plus the interaction of MAT and nonfocal species. We chose the best-fitting model among these four on the basis of the lowest Akaike information criteria (AIC) score (43). To obtain AIC values, we initially fit all models with a binomial error structure; we then refit the best-fitting models using a quasi-binomial error structure to obtain the correct SEs for the estimates.

We constructed a transition matrix for each chamber at each site, pooling observations across nest boxes within a chamber and transforming the raw counts to probabilities, such that columns summed to 1 (see table S1 for the raw number of transitions per chamber). We then used the eigen.analysis function from the popbio library (44) to perform eigenvalue decomposition on the probability matrix, allowing us to compute the Lyapunov stability (that is, the damping ratio, which is the ratio of the dominant eigenvalue to the second largest eigenvalue), the equilibrium frequencies for each species and the empty nest box class, and the transition probabilities for individual species and the empty nest box class.

Because the transition probabilities for each chamber are simple constants that do not incorporate density dependence, the Markov transition model does not forecast species extinctions. However, it does predict an equilibrium vector of relative abundances of each species (and of empty patches) that reflects all possible pairwise transitions in the system. None of the diagonal elements in the empirical matrices equaled 1.0; thus, there were no absorbing states. Instead, there is only a single equilibrium vector of relative abundances for each chamber, and the Lyapunov stability measures the return time to that equilibrium state following a small perturbation to the equilibrium. This Markov model effectively captures the interplay between occupancy, colonization, and extinction because the probabilistic transitions are always conditioned on the current state of the system.

To quantify which attributes of the transition matrices were most strongly contributing to the damping ratios, we examined Spearman’s rank correlation between damping ratio and the following: disturbance (the sum of the first row of the transition matrix that measures the tendency of the system to the empty state), evenness (the variance of the sums of the columns of the transition matrix), and resistance (the sum of the diagonals of the transition matrix that measures the tendency of the system to stay unchanged). We also calculated the return time, the number of time steps until the constant occupancy fraction is achieved under a simulation of 10,000 nest boxes starting in the empty state; we explored whether this alternative metric of stability was correlated with the damping ratio.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Colwell for comments on a previous version of the manuscript. Funding: The U.S. Department of Energy Program for Ecosystem Research (DEFG02-08ER64510) and NSF Dimensions of Biodiversity (1136703) provided funding. Author contributions: R.R.D., N.J.S., A.M.E., and N.J.G. designed the warming experiment. L.M.N., S.L.P., C.A.P., G.W.B., and S.H.C. collected data. S.E.D. and N.J.G. designed the models, performed the analyses, and wrote the first draft. All coauthors contributed to revisions of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. Warming chamber climate data and ant nest box data are deposited at the Harvard Forest Data Archive (http://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu/ data set HF-113).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/10/e1600842/DC1

Levins’ metapopulation, turnover, and persistence models

Alternative demographic and transition matrix model specifications

Linking altered community dynamics with changes in community composition

fig. S1. Frequency of nest box censuses at the two experimental warming arrays.

fig. S2. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S3. Mean proportion of nest boxes colonized per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S4. Mean proportion of nest boxes that went extinct per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S5. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied per chamber at Harvard Forest.

fig. S6. Mean proportion of nest boxes colonized per chamber at Harvard Forest.

fig. S7. Mean proportion of nest boxes that went extinct per chamber at Harvard Forest.

fig. S8. Equilibrium frequencies as a function of chamber temperature for each of the four focal species and empty nest boxes at Duke Forest.

fig. S9. Equilibrium frequencies as a function of chamber temperature for each of the five focal species and empty nest boxes at Harvard Forest.

fig. S10. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied at equilibrium using Levins’ colonization-extinction formula at Duke Forest.

fig. S11. Mean proportion of nest boxes that turn over at Duke Forest.

fig. S12. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied at equilibrium using Levins’ colonization-extinction formula at Harvard Forest.

fig. S13. Mean proportion of nest boxes that turn over at Harvard Forest.

fig. S14. Mean proportion of nest boxes that persisted to the next census per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S15. Mean proportion of nest boxes that persisted to the next census per chamber at Harvard Forest.

table S1. Observed transitions in the nest boxes at Duke and Harvard forests.

table S2. Models of species associations at Duke and Harvard forests.

table S3. Models of temperature effects at Duke Forest.

table S4. Models of temperature effects at Harvard Forest.

table S5. Models of community-wide responses.

table S6. Models of equilibrium frequency as functions of temperature.

table S7. Temperature dependence of individual transition probabilities.

table S8. Transition matrix correlates of community stability.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Walther G.-R., Community and ecosystem responses to recent climate change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B 365, 2019–2024 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark J. S., Carpenter S. R., Barber M., Collins S., Dobson A., Foley J. A., Lodge D. M., Pascual M., Pielke R. Jr, Pizer W., Pringle C., Reid W. V., Rose K. A., Sala O., Schlesinger W. H., Wall D. H., Wear D., Ecological forecasts: An emerging imperative. Science 293, 657–660 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckley L. B., Kingsolver J. G., Functional and phylogenetic approaches to forecasting species’ responses to climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 43, 205–226 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blois J. L., Zarnetske P. L., Fitzpatrick M. C., Finnegan S., Climate change and the past, present, and future of biotic interactions. Science 341, 499–504 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiens J. A., Stralberg D., Jongsomjit D., Howell C. A., Snyder M. A., Niches, models, and climate change: Assessing the assumptions and uncertainties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (Suppl. 2), 19729–19736 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fussmann K. E., Schwarzmüller F., Brose U., Jousset A., Rall B. C., Ecological stability in response to warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 206–210 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 7.E. S. Post, Ecology of Climate Change: The Importance of Biotic Interactions (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilman S. E., Urban M. C., Tewksbury J., Gilchrist G. W., Holt R. D., A framework for community interactions under climate change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 325–331 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelini S. L., Bowles F. P., Ellison A. M., Gotelli N. J., Sanders N. J., Dunn R. R., Heating up the forest: Open-top chamber warming manipulation of arthropod communities at Harvard and Duke Forests. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 534–540 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2013 - The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuble K. L., Pelini S. L., Diamond S. E., Fowler D. A., Dunn R. R., Sanders N. J., Foraging by forest ants under experimental climatic warming: A test at two sites. Ecol. Evol. 3, 482–491 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbers J. M., Community structure in north temperate ants: Temporal and spatial variation. Oecologia 81, 201–211 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamond S. E., Nichols L. M., McCoy N., Hirsch C., Pelini S. L., Sanders N. J., Ellison A. M., Gotelli N. J., Dunn R. R., A physiological trait-based approach to predicting the responses of species to experimental climate warming. Ecology 93, 2305–2312 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.H. S. Horn, in Ecology and Evolution of Communities, M. L. Cody, J. M. Diamond, Eds. (Harvard Univ. Press, 1975). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittman S. E., Gotelli N. J., Predicting community structure of ground-foraging ant assemblages with Markov models of behavioral dominance. Oecologia 166, 207–219 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.H. Caswell, Matrix Population Models: Construction, Analysis, and Interpretation (Sinauer Associates, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertz P. E., Huey R. B., Stevenson R. D., Evaluating temperature regulation by field-active ectotherms: The fallacy of the inappropriate question. Am. Nat. 142, 796–818 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunday J. M., Bates A. E., Kearney M. R., Colwell R. K., Dulvy N. K., Longino J. T., Huey R. B., Thermal-safety margins and the necessity of thermoregulatory behavior across latitude and elevation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 5610–5615 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods H. A., Dillon M. E., Pincebourde S., The roles of microclimatic diversity and of behavior in mediating the responses of ectotherms to climate change. J. Therm. Biol. 54, 86–97 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelini S. L., Diamond S. E., Nichols L. M., Stuble K. L., Ellison A. M., Sanders N. J., Dunn R. R., Gotelli N. J., Geographic differences in effects of experimental warming on ant species diversity and community composition. Ecosphere 5, 1–12 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.L. Lach, C. Parr, K. Abbott, Ant Ecology (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuble K. L., Rodriguez-Cabal M. A., McCormick G. L., Jurić I., Dunn R. R., Sanders N. J., Tradeoffs, competition, and coexistence in eastern deciduous forest ant communities. Oecologia 171, 981–992 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angert A. L., LaDeau S. L., Ostfeld R. S., Climate change and species interactions: Ways forward. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1297, 1–7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blois J. L., Williams J. W., Fitzpatrick M. C., Jackson S. T., Ferrier S., Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9374–9379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huey R. B., Kearney M. R., Krockenberger A., Holtum J. A. M., Jess M., Williams S. E., Predicting organismal vulnerability to climate warming: Roles of behaviour, physiology and adaptation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B 367, 1665–1679 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellard C., Bertelsmeier C., Leadley P., Thuiller W., Courchamp F., Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 15, 365–377 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters R. J., Blanckenhorn W. U., Berger D., Forecasting extinction risk of ectotherms under climate warming: An evolutionary perspective. Funct. Ecol. 26, 1324–1338 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kingsolver J. G., Diamond S. E., Buckley L. B., Heat stress and the fitness consequences of climate change for terrestrial ectotherms. Funct. Ecol. 27, 1415–1423 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebenman B., Jonsson T., Using community viability analysis to identify fragile systems and keystone species. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 568–575 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen I.-C., Hill J. K., Ohlemüller R., Roy D. B., Thomas C. D., Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333, 1024–1026 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malcolm J. R., Liu C., Neilson R. P., Hansen L., Hannah L., Global warming and extinctions of endemic species from biodiversity hotspots. Conserv. Biol. 20, 538–548 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tylianakis J. M., Didham R. K., Bascompte J., Wardle D. A., Global change and species interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 11, 1351–1363 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moritz C., Agudo R., The future of species under climate change: Resilience or decline?. Science 341, 504–508 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheffer M., Carpenter S., Foley J. A., Folke C., Walker B., Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 413, 591–596 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blois J. L., Hadly E. A., Mammalian response to Cenozoic climatic change. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 37, 181–208 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willis K. J., MacDonald G. M., Long-term ecological records and their relevance to climate change predictions for a warmer world. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 267–287 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Post E., Erosion of community diversity and stability by herbivore removal under warming. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 280, 20122722 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grime J. P., Fridley J. D., Askew A. P., Thompson K., Hodgson J. G., Bennett C. R., Long-term resistance to simulated climate change in an infertile grassland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10028–10032 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King J. R., Warren R. J., Bradford M. A., Social insects dominate eastern US temperate hardwood forest macroinvertebrate communities in warmer regions. PLOS ONE 8, e75843 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levins R., Some demographic and genetic consequences of environmental heterogeneity for biological control. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 15, 237–240 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 41.R Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, available at www.R-project.org/ [accessed 28 September 2016] (2015).

- 42.M. J. Crawley, The R Book (John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burnham K. P., Anderson D. R., Huyvaert K. P., AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: Some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 23–35 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stubben C., Milligan B., Estimating and analyzing demographic models using the popbio package in R. J. Stat. Softw. 22, 1–23 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Homer C., Dewitz J., Yang L., Jin S., Danielson P., Xian G., Coulston J., Herold N., Wickham J., Megown K., Completion of the 2011 national land cover database for the conterminous United States—Representing a decade of land cover change information. Photogramm. Eng. Rem. S. 81, 345–354 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/10/e1600842/DC1

Levins’ metapopulation, turnover, and persistence models

Alternative demographic and transition matrix model specifications

Linking altered community dynamics with changes in community composition

fig. S1. Frequency of nest box censuses at the two experimental warming arrays.

fig. S2. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S3. Mean proportion of nest boxes colonized per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S4. Mean proportion of nest boxes that went extinct per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S5. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied per chamber at Harvard Forest.

fig. S6. Mean proportion of nest boxes colonized per chamber at Harvard Forest.

fig. S7. Mean proportion of nest boxes that went extinct per chamber at Harvard Forest.

fig. S8. Equilibrium frequencies as a function of chamber temperature for each of the four focal species and empty nest boxes at Duke Forest.

fig. S9. Equilibrium frequencies as a function of chamber temperature for each of the five focal species and empty nest boxes at Harvard Forest.

fig. S10. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied at equilibrium using Levins’ colonization-extinction formula at Duke Forest.

fig. S11. Mean proportion of nest boxes that turn over at Duke Forest.

fig. S12. Mean proportion of nest boxes occupied at equilibrium using Levins’ colonization-extinction formula at Harvard Forest.

fig. S13. Mean proportion of nest boxes that turn over at Harvard Forest.

fig. S14. Mean proportion of nest boxes that persisted to the next census per chamber at Duke Forest.

fig. S15. Mean proportion of nest boxes that persisted to the next census per chamber at Harvard Forest.

table S1. Observed transitions in the nest boxes at Duke and Harvard forests.

table S2. Models of species associations at Duke and Harvard forests.

table S3. Models of temperature effects at Duke Forest.

table S4. Models of temperature effects at Harvard Forest.

table S5. Models of community-wide responses.

table S6. Models of equilibrium frequency as functions of temperature.

table S7. Temperature dependence of individual transition probabilities.

table S8. Transition matrix correlates of community stability.