Abstract

The End TB Strategy mandates that no tuberculosis (TB)-affected households face catastrophic costs due to TB. However, evidence is limited to evaluate socioeconomic support to achieve this change in policy and practice. The objective of the present study was to investigate the economic effects of a TB-specific socioeconomic intervention.

The setting was 32 shantytown communities in Peru. The participants were from households of consecutive TB patients throughout TB treatment administered by the national TB programme. The intervention consisted of social support through household visits and community meetings, and economic support through cash transfers conditional upon TB screening in household contacts, adhering to TB treatment/chemoprophylaxis and engaging with social support. Data were collected to assess TB-affected household costs. Patient interviews were conducted at treatment initiation and then monthly for 6 months.

From February 2014 to June 2015, 312 households were recruited, of which 135 were randomised to receive the intervention. Cash transfer total value averaged US$173 (3.5% of TB-affected households' average annual income) and mitigated 20% of households' TB-related costs. Households randomised to receive the intervention were less likely to incur catastrophic costs (30% (95% CI 22–38%) versus 42% (95% CI 34–51%)). The mitigation impact was higher among poorer households.

The TB-specific socioeconomic intervention reduced catastrophic costs and was accessible to poorer households. Socioeconomic support and mitigating catastrophic costs are integral to the End TB strategy, and our findings inform implementation of these new policies.

Short abstract

Socioeconomic intervention defrays costs of accessing TB care in impoverished TB-affected households in Peru http://ow.ly/zXfd302fBFG

Introduction

In 2014, nearly 10 million people developed tuberculosis (TB) and 1.5 million died due to TB, mostly in resource-constrained settings [1]. In order to enhance TB control, the World Health Organization's (WHO) End TB Strategy mandates complementing the existing biomedical response with approaches that combat the financial burden of TB. Specifically, the strategy recommends providing social protection for TB-affected households and includes a milestone of zero TB-affected households incurring catastrophic costs by 2020.

Previously, catastrophic costs were defined financially as TB-related out-of-pocket expenses that led to worsening impoverishment of TB-affected households [2–4]. In recent research, we defined a clinically relevant catastrophic costs threshold, demonstrating that TB patients from households that incurred total TB-related household costs of ≥20% of their household annual income were more likely to die, or not complete, or not be cured by, TB treatment [5]. Additionally, this research suggested that such catastrophic costs led to as many adverse outcomes as multidrug-resistant (MDR)-TB [5]. This catastrophic costs' threshold has been included by the WHO within a tool to estimate country-specific TB-related and catastrophic costs of TB patients and their TB-affected households, which is being piloted and rolled-out in sentinel countries in 2015–2016 [4].

However, collecting costs data is complex, labour-intensive, and thus may be logistically difficult for national TB programmes to perform in addition to their routine day-to-day activities, especially in resource-constrained settings. Moreover, in primarily agrarian societies or communities, such data may not truly reflect the financial hardship that some households experience or encompass any related coping strategies. A potential solution may be to collect data on other indicators of financial hardship, weakening or shock, called “dissaving”, as part of catastrophic costs surveillance [6]. Examples of dissaving include households using savings, taking out a loan, taking a child out of education, and/or selling household items or assets. The WHO costs tool includes measurement of dissaving but evidence is needed concerning the accuracy and validity of dissaving as a proxy measure for catastrophic costs.

Social protection, such as cash transfer interventions, aim to reduce or prevent further poverty and vulnerability by improving people's capacity to manage social and/or economic risks [7–14]. Socioeconomic interventions include social protection and may additionally aim to defray TB-related costs, incentivise and enable care and reduce TB vulnerability. Social risks of having TB disease include TB-related stigma whereas economic risks include incurring TB-related costs. TB-related costs may be considered in terms of national economic costs (e.g. impact on or proportion of gross domestic product), health system costs (e.g. healthcare service and provision), and human costs (e.g. direct and indirect costs of patients and their households). In the setting of Peruvian shantytowns, the human costs associated with TB are generally experienced and shared by all the members of the household in which someone receives TB treatment [15]. In this manuscript we focus on costs experienced by TB-affected households that are henceforth referred to as TB-related costs [8–10, 16]. There is minimal operational research assessing the impact of socioeconomic interventions on mitigation of the effects of TB-related costs. Such interventions may be a cost-effective investment from a societal perspective [17] through their potential ability to enhance TB control as part of the post-2015 End TB Strategy.

Socioeconomic support aiming to enhance TB control and elimination may be: 1) “TB-specific” − offered only to TB-affected people or households; 2) “TB-inclusive” − adapting existing support interventions to explicitly include TB-affected people in their eligibility criteria with objectives that include, but are not limited to, TB; or 3) “TB-sensitive” − adapting existing support interventions which do not explicitly include TB-affected people in their eligibility criteria but are expected to impact TB prevention, care, and/or control by being sensitive to TB risk reduction strategies and reaching groups at high risk of TB.

Building on the findings of the Innovative Socioeconomic Interventions Against TB “ISIAT” study [15], we designed a new, more focused, clearly defined TB-specific socioeconomic intervention aiming to support TB-affected households in order to better achieve TB prevention and cure [18]. During a household-randomised controlled study, we performed an initial phase assessment of this intervention in order to optimise its impact for the larger Community Randomised Evaluation of a Socioeconomic Intervention to Prevent TB (CRESIPT). Here we report the economic effects of the intervention during the initial phase of the CRESIPT project, including an evaluation of dissaving as a possible proxy marker for catastrophic costs and an assessment of the intervention's impact on defraying TB-related costs and catastrophic costs.

Methods

Participants, study setting and description of the socioeconomic intervention are provided in greater detail in tables 1 and 2 and in a related publication concerning the intervention's planning and implementation [18].

TABLE 1.

The initial phase of the CRESIPT project: socioeconomic intervention methods, participant recruitment and impact of the intervention [18]

| Study setting |

| The study took place in 32 shantytown communities in Callao, Peru, with an estimated population of one million people and TB rates that are higher than the national average [19] |

| Intervention |

| The intervention aimed to increase: 1) screening for TB in household contacts and MDR-TB testing in TB patients; 2) adherence to TB treatment and chemoprophylaxis; and 3) engagement with socioeconomic support activities |

| This integrated intervention consisted of: |

| Economic support component: conditional cash transfers throughout treatment to defray average household TB-related costs and thereby reduce TB vulnerability, incentivise, empower and enable equitable access to care; and |

| Social support component: household visits and participatory community meetings for information, mutual support, stigma reduction and empowerment |

| The cash transfers of the economic component of the intervention were designed so that if a patient achieved all possible conditions and thereby received all possible cash transfers throughout treatment, this would largely defray their direct out-of-pocket expenses for their entire illness that were previously found to be 10% of annual household income in this study site [5, 18]. It should be noted that current Peruvian National TB Programme guidance recommend a home visit for all diagnosed TB patients to perform contact tracing and provision of food baskets to MDR-TB patients. However, the implementation of these activities varies according to locality and, in some communities, does not occur |

| Participants |

| Inclusion criteria: any patient initiating treatment with the Peruvian National TB Programme for TB disease in health posts in the study setting was invited to participate between February 10 and August 14, 2014 and followed up until June 1, 2015 |

| Exclusion criteria: inability or unwillingness to give informed written consent. For patients who were minors, a parent or guardian was asked to give informed written consent and patients who were old enough were also invited to provide their assent to participate |

| After informed written consent, patient households were randomised to the intervention or control arm: |

| Control TB-affected households: TB-affected households in which a TB patient received the Peruvian National TB Programme standard of care only; and |

| Intervention TB-affected households: TB-affected households in which a TB patient received the Peruvian National TB Programme standard of care plus the socioeconomic intervention |

| Healthy control households: were randomly recruited households not known to have TB-affected household members and recruited concurrently with TB patients. Potential healthy control households were randomly selected from maps of the 32 study site communities. Either this household or the nearest inhabited household to this location was invited to participate during a household visit. All available household members, regardless of age, were invited to participate in the study. Healthy controls were not matched to patients because the study aimed to characterise risk factors for TB outcomes including sex, age, and poverty |

CRESIPT: Community Randomised Evaluation of a Socioeconomic Intervention to Prevent TB; TB: tuberculosis; MDR-TB: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of social and economic support activities provided by the Peruvian National TB Programme (NTP) and the CRESIPT project

| NTP | CRESIPT | |

| Community meetings | Every 2–4 weeks throughout treatment for patient and contacts | |

| Home visits | Rarely occurred (national policy once per patient, but limited resources) | At least once (all patients and their contacts) |

| Information | Mainly to patient, verbal (in health post; National TB Program local clinic) | To patients and their contacts, verbal and written (in health post (National TB Program local clinic), home visits and community meetings) |

| Expert support | Baseline assessment by social worker and/or psychologist (in health post, national policy once for patients but limited resources) | Specialist TB nurse advice (in health post (National TB program clinic), home visits and community meetings) |

| Peer support | Every 2–4 weeks (during community meetings and some home visits) | |

| Stigma support | Group peer sessions specifically addressing stigma (during community meetings) | |

| Civil society organisation | Fostered a civil society organisation of people living with TB (during community meetings) | |

| Food support | Occasional (monthly for selected vulnerable patients: mainly MDR) | Every 2–4 weeks (during community meetings) |

| Travel cost reimbursement | To attend community meetings every 2–4 weeks | |

| Cash transfers also aimed to defray average household TB-related costs, including travel (all patients and their contacts) | ||

| Lost income reimbursement | To reimburse lost earnings for time spent participating in CRESIPT activities every 2–4 weeks | |

| The cash transfers also aimed to defray average household TB-related costs, including average household lost income (all patients and their contacts) | ||

| Cash transfers | Assisted to open free bank account | |

| Cash transfers were provided monthly throughout treatment conditional on adherence, contact screening contacts, and engagement in CRESIPT activities | ||

| Throughout the study, intervention households received an average of US$173 (3.5% of average TB-affected household's annual income), which was mostly spent on food and travel |

TB: tuberculosis; MDR: multidrug resistant; CRESIPT: Community Randomised Evaluation of a Socioeconomic Intervention to Prevent TB. The NTP provided all TB drugs, TB-related consultation and TB tests free of direct charges. Patients paid for their travel to receive this care and also paid for symptomatic medications. Many patients also paid for additional private consultations and other tests, especially prior to being diagnosed with TB. The NTP did not provide any monetary support or reimbursements. Contacts indicates patients' household contacts who spent >6 h per week in the patient's household in the 2 weeks prior to the patient being diagnosed with TB.

General analysis of costs

Continuous data were summarised by their arithmetic means and their 95% confidence intervals and compared with the t-test whether the data was Gaussian or non-Gaussian, because this approach is considered to be robust for health economics data analysis (and facilitates comparison with previous studies) [5, 20–22]. Furthermore, because of the skewed nature of some expenditure data, most median values were zero or close to zero limiting the descriptive usefulness of presenting median values. As described previously [5], any direct expenses, lost income, or annual income recorded as “zero” or missing was replaced with 0.5 Peruvian soles per day, i.e. the midpoint of zero and the lowest unit of measurement, one Peruvian sol. Categorical data were summarised as proportions with 95% confidence intervals and were compared with the z-test of proportions. Operational definitions of the key study variables (TB disease, TB treatment phases, TB costs and dissaving) were used from our group's published research [5] conducted in the same study site in 2004 (table 3).

TABLE 3.

Operational definitions

| TB treatment phases# |

| Pre-treatment: the time from self-reported onset of TB-related symptoms until treatment initiation |

| Intensive treatment phase: the initial phase of daily (or 6 days per week) TB therapy, usually the first two consecutive months of TB treatment |

| Continuation treatment phase: the months following intensive treatment phase in which treatment is given three times per week, usually for four consecutive months |

| During treatment: the intensive treatment phase plus the continuation treatment phase |

| Entire illness: the time from TB-related symptom onset to the end of the continuation treatment phase |

| TB costs¶ |

| Direct medical expenses: costs of medical examinations and medicines |

| Direct non-medical expenses: costs of natural non-prescribed remedies, TB care-related transport, extra food and other miscellaneous expenses caused by the TB illness |

| Direct (“out of pocket”) expenses: the sum of direct medical and non-medical expenses [4, 23, 24] |

| Lost income (indirect expenses): the income the patient estimated that the household lost due to TB illness or TB-related time off work since symptom onset and during treatment [4, 23, 24] |

| Total costs: direct expenses plus lost income |

| TB-related costs: refers collectively to direct expenses, lost income and total costs |

| Income: the money earned by the household, stated monthly or annually |

| Catastrophic costs: a threshold of total costs of the entire TB illness ≥20% of that household's annual income, which were associated with a higher likelihood of TB patient death, abandonment or TB recurrence in a cohort of TB-affected households from impoverished Peruvian shantytowns [5] |

| TB-related costs cohort impact: to estimate the impact of TB-related costs at a cohort level, TB-related costs are expressed as a proportion of average annual income of the entire study cohort of TB-affected households |

| TB-related costs impact: to estimate the impact of TB-related costs at an individual household level, TB-related household costs are expressed as a proportion of the same household's annual income |

| Poverty and dissaving |

| Socioeconomic variables: relatively stable proxy poverty markers including: home ownership, highest patient education level, material that walls were composed of, material that floors were composed of, toilet services, electricity use, water facilities, phone ownership (landline and/or cell), fuel used to cook at home, TV ownership, radio ownership, cooker/stove ownership and refrigerator ownership |

| Poverty score: a composite score using arbitrary units derived by PCA of all the socioeconomic variables [15] |

| Dissaving variables: proxy markers of household financial weakening and shock that included household members having: taken loans (informal and formal); left education (e.g. to care for or accompany patient); sold or pawned household items; used savings; started a new or second job; been asked to eat elsewhere; been asked to move out or find other lodgings; and performed fund-raising events (e.g. buying and cooking food to sell to friends, family, colleagues and others for a small profit) |

| Dissaving score: a composite score using arbitrary units derived by PCA of all the dissaving variables |

TB: tuberculosis; PCA: principal component analysis. #: these treatment definitions apply to all TB patients, irrespective of whether they had multidrug-resistant (MDR)-TB or non-MDR-TB. It must be noted, however, that Peruvian National TB Programme guidance recommends that the intensive phase for MDR-TB patients is 6 months and the continuation phase is at least 12 months of treatment (e.g. a total of at least 18 months of treatment). Treatment is tailored to patients with MDR-TB by a multidisciplinary team according to their resistance profile and “intensive” and “continuation” treatment phase durations may vary depending on treatment response. All patients with MDR-TB recruited during the study received ambulatory treatment. ¶: income, expenses and costs are all measured in Peruvian Soles (average US$1 equivalent to 2.9 Peruvian Soles during the study period) at the household level unless otherwise stated.

Costs and poverty

A locally validated questionnaire [5, 15] was updated and used to interview patients and collect sociodemographic data concerning household income and expenses throughout TB illness. Interviews were conducted at baseline with TB patients in intervention and control arms, as well as healthy controls. For all patients, this baseline interview occurred prior to or at the time at which treatment commenced. All patients (but not healthy controls) were subsequently interviewed after 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 weeks. At all baseline and subsequent interviews, data was collected characterising earnings, income, expenses, employment (paid or unpaid), days unable to work due to illness, additional household food expenditure due to TB illness (e.g. over and above normal food expenditure), and crowding since the previous interview. As per previous research [5], crowding was defined as both a continuous variable (number of people per room) and a dichotomous variable (percentage of households with greater than cohort median people per room). A final “exit” interview took place at 24 weeks or, in those who continued TB treatment beyond 24 weeks, at 28 weeks of treatment. The baseline and exit interviews (but no other interview) included anthropometric measurement of height and weight, calculation of body mass index (BMI), and a detailed assessment of 13 key stable variables associated with socioeconomic position (table 3). These variables were used to create a composite household poverty index score in arbitrary units using principal component analysis (PCA), as described previously [5]. The Eigenvector loading values derived by PCA analysis were analysed in order to assess which of the socioeconomic variables contributed the most to the poverty score in this setting (variables with higher Eigenvector loading values being more discriminatory). The proportion of intervention patient households' TB-related costs that were defrayed by the conditional cash transfers was calculated. Additionally, changes in poverty score and BMI from recruitment to the exit interview were analysed in order to evaluate the impact of the intervention on nutritional and other poverty-related TB risk factors.

Dissaving

Elements of “dissaving” specifically related to the patient's TB illness were recorded at each interview (table 3). Cumulative dissaving episodes (i.e. each separate occasion on which an element of dissaving occurred) were also measured. A composite dissaving score was then derived by PCA from all of the dissaving variables [5]. The dissaving score was measured as a continuous variable in arbitrary units with the mean dissaving score of the patient cohort being 0 units. A higher score implied greater dissaving and thus implied that the TB illness was causing a greater financial burden. The Eigenvector loading values derived by PCA analysis were analysed in order to assess which of the dissaving variables had the highest discriminatory power to explain the dissaving score in the setting. Univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses with stepwise exclusion of non-contributory variables were used to assess the association between dissaving and socioeconomic variables including catastrophic costs. For these analyses the dissaving score was considered as a binary variable of higher-than versus lower-than average dissaving. This dissaving analysis tested whether dissaving may be a possible proxy indicator of catastrophic costs (see introduction section).

Data shown

Data concerning TB-related costs, catastrophic costs, and dissaving is shown for both intervention TB-affected households and control TB-affected households. Data concerning the effect of the socioeconomic intervention on defraying costs are only shown for the intervention TB-affected households. This is because control TB-affected households did not receive the socioeconomic intervention and thus their TB-related costs were not defrayed.

Ethical approval

The project was approved by the ethical committee of the Peruvian Ministry of Health, Callao, Peru and all participants gave informed written consent prior to participation.

Results

Participants

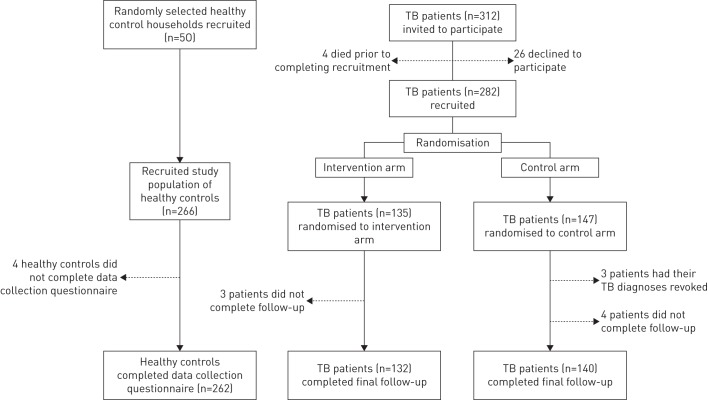

The recruitment period was from February 10, 2014 to August 14, 2014 when the a priori study sample size was reached. Data collection on TB-affected household costs continued until June 1, 2015. Figure 1 shows TB-affected household recruitment and participation: 312 TB patients each from separate households were invited to participate, of whom 90% (282 out of 312) were recruited. Of these, 147 were randomised to the control arm and received normal standard of care only (“control TB-affected households”) and 135 were randomised to the intervention arm and additionally received the socioeconomic intervention (“intervention TB-affected households”). Of the intervention TB-affected households, 98% (132 out of 135) completed final follow-up. All 135 intervention TB-affected households had TB-related costs data available for analysis. Concurrently, healthy control households were randomly recruited from the same 32 study site communities. 98% (262 out of 266) of healthy control household members gave informed consent and participated.

FIGURE 1.

Participant recruitment and randomisation. Recruitment constituted completing informed consent and a recruitment questionnaire. Dashed arrows refer to participants who were not included in the final analysis. 25 (8%) out of 321 patients had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) of whom 10 were randomised to the intervention arm and 15 to the control arm.

Descriptive data

Baseline demographic data are summarised in table 4, which compares all patients with healthy controls, and their households. There were no significant demographic differences between intervention and control patients or their households. TB patients' household income in Peruvian soles was lower during the intensive treatment phase (PEN1109, 95% CI 1011–1206; p<0.0001) and maintenance treatment phase (PEN1155, 95% CI 1050–1261; p=0.004) than pre-treatment (PEN1316, 95% CI 1210–1421) (table 4). Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that being a TB patient rather than a healthy control was independently associated with being poorer (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.4; p=0.002) (table 5).

TABLE 4.

Baseline demographic characteristics of patients and healthy controls and their households

| Patients | Healthy controls | p-value# | ||

| Intervention | All | All | ||

| Subjects n | 135 | 282 | 262 | |

| General | ||||

| Age years median (interquartile range) | 30 (21–45) | 28 (21–44) | 25 (11–44) | 0.02 |

| Male % (95% CI) | 64 (55–72) | 62 (56–67) | 50 (44–56) | 0.006 |

| Socioeconomic | ||||

| Education level % (95% CI) | ||||

| Preschool minor | 3 (0–6) | 2 (0–4) | 5 (2–8) | 0.1 |

| Illiterate | 3 (0–6) | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | 0.5 |

| Primary school incomplete | 12 (6–17) | 9 (6–12) | 12 (8–17) | 0.2 |

| Primary school complete | 10 (5–15) | 7 (4–10) | 11 (7–15) | 0.1 |

| Secondary school incomplete | 29 (22–37) | 27 (22–33) | 21 (16–26) | 0.1 |

| Secondary school complete | 27 (20–35) | 32 (27–38) | 32 (26–38) | 0.8 |

| Higher education | 16 (10–22) | 20 (16–25) | 11 (7–15) | 0.01 |

| Employment % (95% CI) | ||||

| Paid employment | 28 (20–36) | 29 (24–35) | 39 (33–45) | 0.02 |

| Unpaid employment | 25 (17–32) | 23 (18–28) | 16 (12–21) | 0.05 |

| Student | 6 (2–10) | 8 (5–12) | 30 (24–36) | <0.0001 |

| Minor | 3 (0–6) | 2 (0–4) | 5 (2–8) | 0.1 |

| Unemployed | 36 (28–44) | 36 (30–41) | 6 (3–9) | <0.0001 |

| Monthly household income Peruvian Soles mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Throughout entire illness | 1190 (1071–1309) | 1231 (1138–1325) | 2204 (2002–2407) | <0.0001 |

| Pre-treatment | 1358 (1206–1510) | 1316 (1210–1421) | NA | NA |

| Intensive phase | 1091 (976–1207) | 1109 (1011–1206) | NA | <0.0001¶ |

| Maintenance phase | 1082 (958–1207) | 1155 (1050–1261) | NA | 0.004+ |

| Crowding people/room mean (95% CI) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | 2 (1.8–2.1) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 0.08 |

| Proportion poor % (95% CI) | ||||

| Poorer tercile | 41 (32–49) | 39 (34–45) | 27 (22–32) | 0.002 |

| Poor tercile | 30 (23–38) | 33 (27–38) | 36 (30–42) | 0.4 |

| Less poor tercile | 29 (21–37) | 28 (23–33) | 37 (31–43) | 0.03 |

| Days went to bed hungry in the past month mean (95% CI) | 1.7 (1.0–2.4) | 1.5 (1.0–2.0) | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) | 0.003 |

| TB and health | ||||

| Sputum smear positive % (95% CI) | 40 (32–48) | 40 (34–45) | 0 | NA |

| MDR % (95% CI) | 7 (2–11) | 9 (5–12) | 0 | NA |

| Previous TB episode % (95% CI) | 18 (11–25) | 23 (18–28) | 5 (0–15) | 0.05 |

| BMI (mean (95% CI)) | 22 (21–23) | 22 (21–22) | 24 (23–25) | <0.001 |

There was no significant difference between household income comparing intensive versus maintenance phase. TB: tuberculosis; MDR: multidrug resistant; BMI: body mass index; NA: not applicable. #: compare all healthy controls versus all patients using univariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and sex; ¶: pre-treatment versus intensive phase; +: pre-treatment versus maintenance phase.

TABLE 5.

Univariate and multiple logistic regression of specific poverty indicators associated with tuberculosis (TB) disease comparing patients versus healthy controls

| Patients# | Controls¶ | Univariate logistic regression | Multiple logistic regression | |||

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Poor (% poorer than median poverty score) | 50 (44–56) | 38 (32–43) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.002 | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.002 |

| Crowded (% above median number of people per room) | 46 (41–52) | 53 (47–59) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.2 | ||

| Head of household did not complete secondary school (%) | 47 (40–53) | 52 (46–58) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.3 | ||

| Food insecurity (% above median days of going hungry in past month) | 29 (23–34) | 21 (16–26) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 0.03 | ||

| Not in paid employment (%) | 62 (56–68) | 31 (25–36) | 4.7 (3.2–6.9) | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| Lower monthly household income (% below median income) | 58 (52–64) | 27 (21–32) | 3.7 (2.6–5.4) | <0.001 | NA | NA |

After univariate logistic regression adjusting for age and sex, contributory variables (p≤0.1) were entered into a multiple logistic regression analysis. The variables that have blank cells in the multiple logistic regression columns were those non-contributory variables excluded from the final model. The OR (95% CI) and p-values of the association of being poor and having TB disease are identical for the univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses because this was the only variable that remained significantly associated with TB disease after stepwise multiple logistic regression was performed. The variables “not in paid employment” and “lower monthly household income” were not included in the multiple regression model because these variables were strongly collinear with the variable “poor”. Body mass index was not included in the analysis because this variable is strongly and acutely influenced by having TB disease. NA: not applicable. #: n=282; ¶: n=262.

Costs: direct expenses and lost income

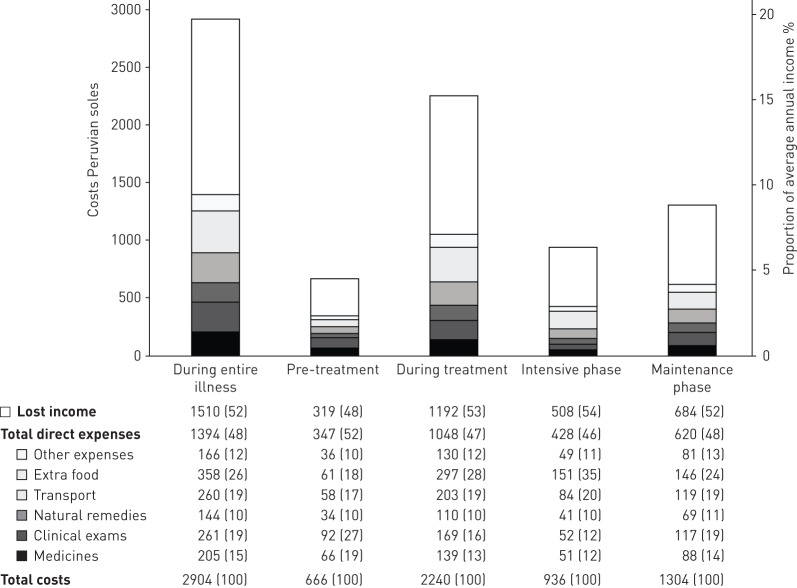

Constituent direct expenses and lost income are summarised in figure 2. Of the total direct costs throughout the entire illness, non-medical expenses were greater than medical (67%, 95% CI 65–68, versus 33%, 95% CI 32–35; p<0.0001), due to additional food and transport expenses during treatment predominantly. Direct expenses and lost income were higher during treatment than pre-treatment (direct expenses 7.1%, 95% CI 6.2–8.1, versus 2.3%, 95% CI 1.9–2.8, of average TB-affected household annual income; p<0.0001; and lost income 8.0%, 95% CI 6.5–9.2, versus 2.2%, 95% CI 1.8–2.6; p<0.0001). As a proportion of total costs during the entire illness, lost income was similar to direct expenses (48%, 95% CI 48–52%, versus 52%, 95% CI 50–54; p=0.3) (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Tuberculosis affected household direct expenses, lost income and total costs by treatment phase.

Total costs

Total costs are summarised in figure 2. Total costs as a proportion of average TB-affected household income were significantly lower pre-treatment than during treatment (4.5%, 95% CI 3.8–5.3, versus 15%, 95% CI 13–18; p<0.0001), the intensive treatment phase (6.3%, 95% CI 5.6–7.1; p<0.02), or the maintenance treatment phase (9.2%, 95% CI 6.8–10.8; p<0.0001). Total costs were higher during maintenance treatment phase than intensive treatment phase (9.2%, 95% CI 6.8–10.8, versus 6.3%, 95% CI 5.6–7.1; p=0.0005) predominantly owing to the duration of the maintenance treatment phase being twice as long as the intensive treatment phase. However, costs per month during the intensive treatment phase costs were approximately 1.5-times greater than costs per month during the maintenance treatment phase (p=0.001).

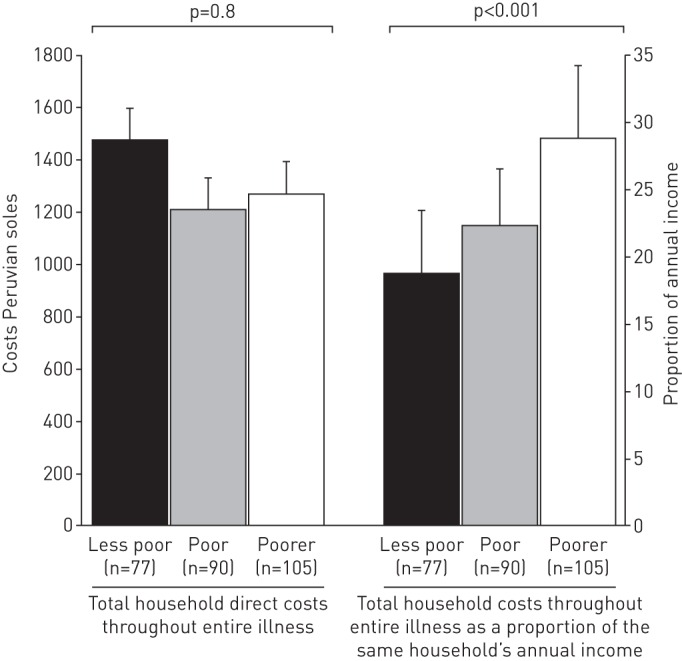

Poverty and TB-related costs

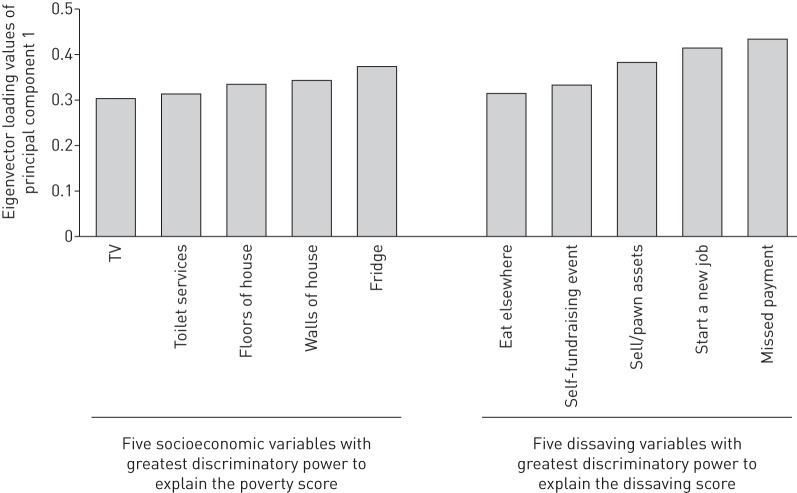

In poorer versus less poor households, direct expenses in Peruvian soles throughout the entire illness were lower (mean direct expenses PEN1267, 95% CI 1070–1464, versus PEN1470, 95% CI 1001–1938) (figure 3). However, total costs made up a greater proportion of poorer household's annual income (poorest households 29%, 95% CI 23–34, versus least poor households 19%, 95% CI 14–23; p<0.001) (figure 3). The socioeconomic variables with the highest discriminatory power to explain the poverty score in this setting were: quality of wall material (e.g. a wall made of mud/straw versus bricks); quality of floor material (e.g. a floor made of mud/rubble versus concrete); type of toilet (e.g. no toilet or rudimentary outdoor latrine versus a flushing toilet in a specific separate room of the house); not having a refrigerator; and not having a television (figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Total direct household expenses during the entire illness and total costs during the entire illness as a proportion of annual income by poverty tercile (n=272). This analysis is comparable with previous research [5].

FIGURE 4.

Variables with the highest Eigenvector loading values derived by principal component analysis. Higher Eigenvector values represent a higher discriminatory power of that specific variable to explain the poverty score and dissaving scores.

Dissaving and the association of dissaving with catastrophic costs

95% (95% CI 92–98) of patient households experienced at least one episode of dissaving during their entire TB illness. Patient households experienced an average of 1.3 episodes (95% CI 1.1–1.5) of dissaving pre-treatment, 3.4 episodes (95% CI 3.0–3.8) in the intensive phase of treatment, and 3.7 episodes (95% CI 3.2–4.2) in the maintenance phase of treatment. Thus, cumulatively, patient households experienced an average of 8.4 (95% CI 7.5–9.2) episodes of dissaving during the entire TB illness. Multiple regression analysis of the dissaving score demonstrated that patients who belonged to households with more than average dissaving were independently more likely to: incur catastrophic costs (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.1; p=0.02), be poorer (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.0; p<0.03), and have more food insecurity (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–3.8; p=0.008) (table 6). The variables with the highest discriminatory power to explain the dissaving score in this setting were: starting a new job; undertaking small scale fundraising activities; selling or pawning household items; missing scheduled payments; and being asked to eat elsewhere to conserve household food (figure 4).

TABLE 6.

Patient household (n=282) dissaving score associations with health and socioeconomic variables

| Variable | Dissaving score | Univariate logistic regression | Multiple logistic regression | ||

| Mean | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Catastrophic costs | |||||

| Incurred | 0.58 | 2.4 (1.5–3.9) | 0.001 | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 0.02 |

| Not incurred | −0.43 | ||||

| Poverty | |||||

| Poorer | 0.37 | 2.3 (1.4–3.7) | 0.001 | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | 0.03 |

| Less poor | −0.35 | ||||

| Food insecurity | |||||

| High | 0.3 | 2.6 (1.5–4.5) | 0.001 | 2.2 (1.2–3.8) | 0.008 |

| Low | −0.26 | ||||

| Secondary education | |||||

| Incomplete | 0.36 | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) | 0.03 | ||

| Complete | −0.165 | ||||

| Employment | |||||

| Unpaid/no work | 0.16 | 1.1 (0.68–1.8) | 0.6 | ||

| Paid work | −0.23 | ||||

| Symptom duration | |||||

| Longer | 0.09 | 1.4 (0.84–2.2) | 0.2 | ||

| Shorter | −0.068 | ||||

| Type of TB | |||||

| Non-MDR | 0.008 | 1.1 (0.49–2.6) | 0.8 | ||

| MDR | −0.09 | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 0.07 | 1.1 (0.66–1.7) | 0.8 | ||

| Male | −0.04 | ||||

The patient cohort had a median average dissaving score of 0. Higher (more positive) scores indicate greater dissaving and hence greater financial shock. Health and socioeconomic variables were analysed for association with having a greater than average dissaving score by univariate logistic regression. Multiple logistic regression was then performed with stepwise exclusion of non-contributory (p>0.1) variables. The variables that have blank cells in the multiple logistic regression columns were those non-contributory variables excluded from the final model. The variable “secondary education” was entered but was significantly associated in the multiple regression model. Secondary education, employment, symptom duration, type of TB and sex all refer to the patient. A complementary linear regression analysis of the association of a higher dissaving score with health and socioeconomic variables showed a similar pattern of significance with a higher dissaving score being independently associated with incurring catastrophic costs (coefficient 0.30 (95% CI 0.047–0.55), p=0.02) and having greater food insecurity (coefficient 0.38 (95% CI 0.12–0.64), p=0.004). TB: tuberculosis; MDR: multidrug resistant.

Conditional cash transfers and mitigation of direct costs total costs and catastrophic costs

122 (90%) out of 135 intervention TB-affected households received at least one conditional cash transfer. These 122 intervention TB-affected households received a total of 890 conditional cash transfers (80% of potential conditional cash transfers), receiving on average a total of 520 Peruvian soles (US$173) of a maximum possible total of 640 Peruvian Soles (US$230). The average US$173 received is equivalent to 3.5% of average TB-affected household annual income or 42% of average TB-affected household monthly income [5, 18]. Fidelity to the intervention and proportion of specific conditional cash transfers met (e.g. those for adherence to medication versus those for social support) are described in greater detail in a related publication [18].

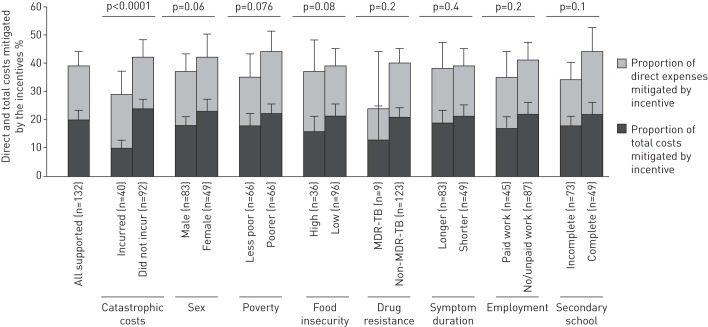

The conditional cash transfers defrayed 20% (95% CI 15–25%) of total costs, 39% (95% CI 37–43%) of direct costs (figure 5), and 19% of lost income. Overall, 36% of patient households incurred catastrophic costs. Compared to control households, intervention households were less likely to incur catastrophic costs (30%, 95% CI 22–38% of intervention households versus 42%, 95% CI 34–50% of control households; p=0.002) (figure 5). Post hoc analysis showed that, in households that incurred catastrophic costs, there was no significant difference between intervention and control households in the proportion who had higher than average dissaving score (52%, 95% CI 36–69% intervention versus 62%, 95% CI 49–75% control households; p=0.3).

FIGURE 5.

Catastrophic costs incurred by intervention (n=132) and control (n=140) households. #: regression analysis adjusted for household clustering and confounders including food insecurity, poverty level, household crowding, highest level of education of head of household, resistance profile of patient and employment of patient; ¶: regression analysis for household clustering.

Equity

The data in the two pairs of columns at the left of figure 6 show that the conditional cash transfers defrayed total costs to a greater extent in poorer households (22%, 95% CI 19–25%, versus 18%, 95% CI 14–22%; p=0.08) and for female patients (23%, 95% CI 19–27, versus 18%, 95% CI 15–21%; p=0.06) (figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Intervention incentives as a proportion of direct expenses and total costs of the household. Incentives refer to conditional cash transfers received by the intervention patient households only (n=132). MDR-TB: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. p-values are univariate logistic regression of each binary variable against total costs defrayed by the incentives.

Conditional cash transfers and poverty-related TB risk factor reduction

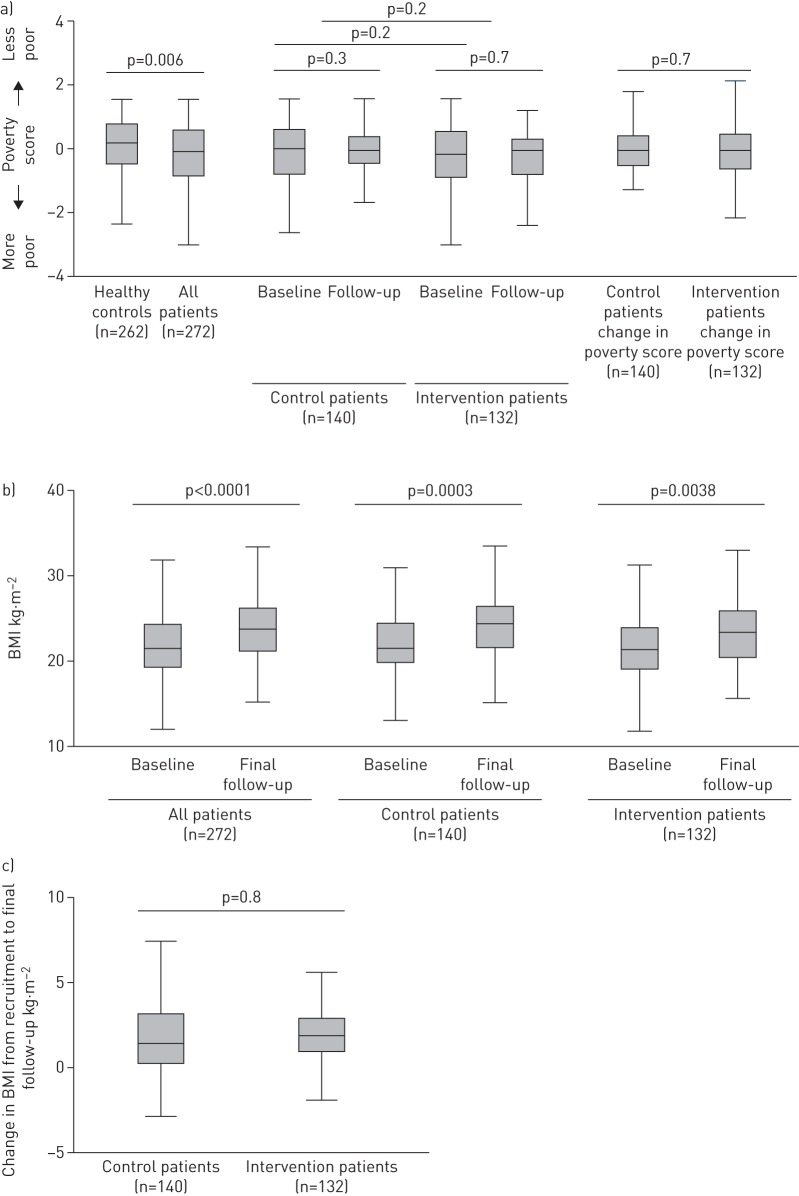

Figure 7a shows the change in poverty score from baseline to final follow-up for control versus intervention patients. There was no significant difference in poverty score or change in poverty score in control patients, intervention patients, or control versus intervention patients. BMI increased significantly from baseline to final follow-up in the intervention patients (2.2 kg·m−2 increase from 22 kg·m−2 (95% CI 21–23 kg·m−2) to 24.2 kg·m−2 (95% CI 23–25 kg·m−2); p=0.0003) and also the control patients (1.6 kg·m−2 increase from 21.6 kg·m−2 (95% CI 21–22 kg·m−2) to 23.2 kg·m−2 (95% CI 22–24 kg·m−2); p<0.004) (figure 7b). There was a nonsignificant trend towards intervention patients' BMI increasing to a greater extent than control patients (figure 7c). Post hoc subgroup analyses of the poorest third of patients or of the subset of patients who experienced catastrophic costs also showed no statistically significant effect of the intervention on BMI, savings, income or poverty score (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

a) Poverty score and changes in poverty score between all patients and healthy controls at baseline, and intervention patients and controls at baseline and follow-up. p-values are the difference of poverty score between all patients and healthy controls, and the change in poverty score from baseline to follow-up in and between intervention and control patients. b) Body mass index (BMI) at baseline and final follow-up in all patients, supported patients and controls. p-values represent the difference in BMI between baseline and follow-up in univariate logistic regression. c) Change in BMI from baseline to follow-up in intervention patients and controls. p-values represent the difference in change in BMI between patient and control arms in univariate logistic regression.

Discussion

We evaluated the effects of a TB-specific socioeconomic intervention [18] including cash transfers on mitigation of the effects of TB-related costs in impoverished Peruvian shantytowns. The financial burden of TB was high, especially amongst poorer TB-affected households, reinforcing Virchow's 150-year old assertion that TB is a social disease [5, 25, 26]. Over one-third of the TB-affected households experienced catastrophic costs and thus were at increased risk of adverse treatment outcome [5]. Households with greater dissaving were nearly twice as likely to incur catastrophic costs, suggesting that dissaving may be a useful and simple proxy indicator of catastrophic costs risk. The intervention defrayed only a fifth of patient households' TB-related costs but, despite this, households that were randomised to receive the intervention were less likely to incur catastrophic costs. TB-related costs were defrayed to a greater extent in poorer households and for female patients, suggesting that the intervention was equitable to these vulnerable groups. This evidence suggests a socioeconomic intervention including a social protection component can contribute to defraying TB-related costs, reduce the likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs, and may inform future implementation of such interventions in line with the post-2015 global End TB Strategy.

Impact of the socioeconomic intervention on defraying TB-related costs and catastrophic costs

The findings of this current research are important because they indicate that a socioeconomic intervention reduced the likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs: an encouraging finding that contributes to WHO's goal of eliminating catastrophic costs by 2035. However, despite reducing the likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs, the impact of the socioeconomic intervention may have been limited by the fact that the conditional cash transfers defrayed only 20% of patient households' total TB-related costs. During planning of the intervention, it had been estimated that if implemented nationally this conditional cash transfer programme would increase the Peruvian TB programme budget by between 5% and 26% per patient [18]. Focus group discussions with key stakeholders including local staff of the Peruvian TB programme and a civil society of TB-affected people suggested that such an increase in programme expenditure was locally appropriate, affordable and potentially sustainable [18]. A nationwide socioeconomic support programme designed for TB-affected households may benefit from collaborative implementation between the national TB programme and other social development and welfare organisations that share cash transfer and delivery costs. During planning of CRESIPT, leading members of the Peruvian national cash transfer programme “JUNTOS” were consulted as to the possibility of extending the reach of the scheme to the urban, TB-affected households of the study communities. However, this was not possible as JUNTOS provides cash transfers exclusively to female heads of household in rural communities [18]. Therefore, to enhance the future impact of the intervention in Peru, it will likely be necessary to increase the proportion of costs defrayed by conditional cash transfers in order to further incentivise TB-affected households, eliminate catastrophic costs, reduce TB vulnerability, and enable improved access to TB treatment and care. This could be achieved by a combination of: reducing system costs (e.g. through rapid diagnosis, and improved access to treatment and chemoprophylaxis); increasing the value of the cash transfers; and increasing access to and uptake of conditional cash transfers (e.g. stratifying the intervention so that high-risk groups receive greater and more frequent socioeconomic support).

Dissaving and the association of dissaving with catastrophic costs

Dissaving is a simple, proxy measure of financial shock [27]. A key research question to be answered prior to widespread adoption of dissaving assessment is how well the prevalence of certain dissaving measures correlates with likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs. This is important because certain communities (e.g. pastoralists) may not commonly use cash or banking services and, therefore, collecting pecuniary costs data only is likely to overlook the economic impact TB has on often marginalised and vulnerable TB-affected households within that community. In the current study setting, dissaving was associated with vulnerable, underserved individuals or households. Patients from households with more than average dissaving were poorer, and more likely to incur catastrophic costs and have greater food insecurity. In addition to a recently published study demonstrating the correlation of dissaving with TB-related costs in different settings [27], our current results provide evidence to inform the potential role of dissaving and provide provisional support for dissaving as a proxy marker of catastrophic costs. Our previous research has shown that catastrophic costs were associated with adverse TB treatment outcome and may be assumed to have a negative effect on TB control. The same may be the case for dissaving. If dissaving was to be adopted as a proxy indicator of catastrophic costs, it is probable that local adaptation of dissaving measures will be necessary. In specific settings, certain dissaving variables may be more relevant to, and correspond more closely with, the likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs. For example, in rural sub-Saharan Africa where formal loans or payments may be less frequent, other dissaving variables such as selling livestock may be more important contributors to dissaving [2]. In addition, while there is scope for measuring dissaving elements longitudinally as a binary variable at different time points throughout TB treatment (e.g. loan taken, up to present day), collecting only dissaving data would risk losing the richness of quantitative costs data and the opportunity to estimate the equivalent cash transfer amounts required to defray TB-related costs. Piloting of the WHO TB costs tool including dissaving measures may soon shed new light on this under-researched area.

Equity of the socioeconomic intervention on TB-related costs mitigation

There was evidence suggesting the intervention was equitable because the proportion of direct expenses, lost income, and total costs defrayed by conditional cash transfers was higher in poorer households and female patients. These findings are encouraging because such vulnerable and marginalised patient groups have previously been found to have reduced access to TB care and prevention in the study setting, and thus are more likely to experience adverse TB treatment outcome [5, 28]. In order to reach these underserved groups in the future, national TB-specific socioeconomic interventions may benefit from a broader approach than simply money and education, including cross-sector provision of improved access to health insurance, social housing, housing improvements (e.g. optimising ventilation), employment services (nearly half of total TB-related costs were due to lost income), and multidisciplinary drug and alcohol addiction clinics (services not widely available during the study period in the study setting). In addition, alternative forms of DOT may be beneficial to reduce TB-related financial burden and allow an early return to work, such as video-observed or peer-observed therapy.

Limitations

First, the study sample size was determined by TB outcomes, so no a priori power calculations were made to evaluate the impact of the intervention on financial outcomes. In addition, the impact of frequency of conditional cash transfers on TB-related costs and household finances was not analysed during this preliminary phase of CRESIPT but will be evaluated during the main CRESIPT study. Secondly, despite the encouraging findings concerning equity of the intervention, research nurses reported their subjective impression that patients who declined to participate in the study were much more commonly from groups associated with high-risk of adverse treatment outcome (including the formerly incarcerated, homeless and/or those with drug addictions). However, this qualitative observation cannot be quantitatively verified because these patients chose not to give informed consent and so we were unable to formally collect data on their specific risk factors. Thirdly, costs of accessing treatment for comorbidities such as HIV and diabetes throughout TB illness were not specifically examined during this study. However, only 6% of the cohort had diabetes and 5% HIV and these comorbidities were equally distributed in both the intervention and control TB-affected households, so it is unlikely that this would have influenced our results. Fourthly, we only studied the financial effects of MDR-TB for 6–7 months, whereas patients with MDR TB are usually treated for 18 months or more. We decided a priori to analyse the catastrophic costs of both MDR-TB and non-MDR-TB patients together for 6–7 months, given the small number of MDR-TB patients, and in order to be consistent with our previous published research of catastrophic costs of TB-affected households [5]. Finally, there is currently no standardised, accepted method by which to measure mitigation of the effects of catastrophic costs or defraying of TB-related costs, the findings from Peru (an upper/middle-income economy country) may not be generalisable to other countries globally, and the impact of conditional cash transfers may be different if implemented within national TB programmes' day-to-day practice by programmes themselves rather than as part of a household-randomised study.

Conclusions

Accessing TB care that provided TB tests and treatment free of charge was associated with higher dissaving, high TB-related costs, and frequent catastrophic costs in Peruvian shantytowns, especially for poorer households. This research provides preliminary evidence concerning the use of dissaving as a proxy indicator of catastrophic costs. A novel socioeconomic intervention defrayed a substantial proportion of TB-related costs, especially for female patients and poorer households, and reduced the likelihood of incurring catastrophic costs. Informed by these findings, the cash transfers have been increased in value and the impact of the socioeconomic intervention on TB health outcomes is ready to be evaluated during the CRESIPT study.

Footnotes

Support statement: This study was supported by Joint Global Health Trials (award MR/K007467/1 from a consortium of the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council and UK-AID/Dept For International Development), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation award OPP1118545, the Wellcome Trust award 105788/Z/14/Z and IFHAD. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Open Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at erj.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Global Tuberculosis Report 2014 Geneva, WHO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laokri S, Dramaix-Wilmet M, Kassa F, et al. . Assessing the economic burden of illness for tuberculosis patients in Benin: determinants and consequences of catastrophic health expenditures and inequities. Trop Med Int Health 2014; 19: 1249–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ukwaja KN, Alobu I, Abimbola S, et al. . Household catastrophic payments for tuberculosis care in Nigeria: incidence, determinants, and policy implications for universal health coverage. Infect Dis poverty 2013; 2: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauch V, Woods N, Kirubi B, et al. . Assessing access barriers to tuberculosis care with the tool to Estimate Patients Costs: pilot results from two districts in Kenya. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingfield T, Boccia D, Tovar M, et al. . Defining catastrophic costs and comparing their importance for adverse tuberculosis outcome with multi-drug resistance: a prospective cohort study, Peru. PLoS Med 2014; 11: e1001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laokri S, Weil O, Drabo KM, et al. . Removal of user fees no guarantee of universal health coverage: observations from Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ 2013; 91: 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Combating poverty and inequality: structural change, social policy and politics France, UNRISD, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatham House. Social protection interventions for tuberculosis control: the impact, the evidence, and the way forward 2012. www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/GlobalHealth/170212summary.pdf Date last accessed: September 8, 2016. Date last updated: May 1, 2012.

- 9.Boccia D, Hargreaves J, Lönnroth K, et al. . Cash transfer and microfinance interventions for tuberculosis control: review of the impact evidence and policy implications. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 7: CD008137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organisation. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage Geneva, WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNAIDS Expanded Business Case. Enhancing Social Protection Geneva, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Social protection floor of a fair and inclusive globalization Geneva, International Labour Office, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doetinchem O, Xu K, Carrin G. Conditional cash transfers: What's in it for health? Technical Briefs for Policy Makers. Number 1 Geneva, WHO, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha C, Montoya R, Zevallos K, et al. . The Innovative Socio-economic Interventions Against Tuberculosis (ISIAT) project: an operational assessment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15: Suppl 2, S50–S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laxminarayan R, Klein E, Dye C, et al. . Economic benefit of tuberculosis control. Policy research working paper 4295 Geneva, WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grede N, Claros JM, de Pee S, et al. . Is there a need to mitigate the social and financial consequences of tuberculosis at the individual and household level? AIDS Behav 2014; 18: Suppl 5, 542–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wingfield T, Boccia D, Tovar MA, et al. . Designing and implementing a socioeconomic intervention to enhance TB control: operational evidence from the CRESIPT project in Peru. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. 2014 Boletín epidemiológico Callao 2014. Dirección regional de salud de Callao, Oficina de epidemiología, semana epidemiológica (SE) Número 10 del 02/03/2014 al 08/03/2014. Tuberculosis. www.diresacallao.gob.pe/wdiresa/documentos/boletin/epidemiologia/20140409-052600-a7d70d06.pdf Date last accessed: September 8, 2016. Date last updated: March 8, 2014.

- 20.Barter DM, Agboola SO, Murray MB, et al. . Tuberculosis and poverty: the contribution of patient costs in sub-Saharan Africa – a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ 2000; 320: 1197–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis and interpretation of cost data in randomised controlled trials: review of published studies. BMJ 1998; 317: 1195–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann G, Nhlema Simwaka B, Kemp JR, et al. . Can Malawi's poor afford free tuberculosis services? Patient and household costs associated with a tuberculosis diagnosis in Lilongwe. 033167. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajeswari R, Muniyandi M, Balasubramanian R, et al. . Perceptions of tuberculosis patients about their physical, mental and social well-being: a field report from south India. Soc Sci Med 2005; 60: 1845–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raviglione M, Krech R. Tuberculosis: still a social disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15: 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, et al. . Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 2240–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madan J, Lönnroth K, Laokri S, et al. . What can dissaving tell us about catastrophic costs? Linear and logistic regression analysis of the relationship between patient costs and financial coping strategies adopted by tuberculosis patients in Bangladesh, Tanzania and Bangalore, India. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onifade DA, Bayer AM, Montoya R, et al. . Gender-related factors influencing tuberculosis control in shantytowns: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]