Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) plays a pivotal signaling role in inflammatory response; because S1P1 modulation has been identified as a therapeutic target for various diseases, a PET tracer for S1P1 would be a useful tool. Fourteen fluorine-containing analogues of S1P ligands were synthesized and their in vitro binding potency measured; four had high potency and selectivity for S1P1 (S1P1 IC50 < 10 nM, >100-fold selectivity for S1P1 over S1P2 and S1P3). The most potent ligand, 28c (IC50 = 2.63 nM for S1P1) was 18F-labeled and evaluated in a mouse model of LPS-induced acute liver injury to determine its S1P1-binding specificity. The results from biodistribution, autoradiography, and microPET imaging showed higher [18F]28c accumulation in the liver of LPS-treated mice than controls. Increased expression of S1P1 in the LPS model was confirmed by immunohistochemical analysis (IHC). These data suggest that [18F]28c is a S1P1 PET tracer with high potential for imaging S1P1 in vivo.

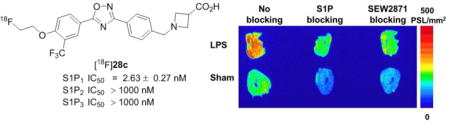

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

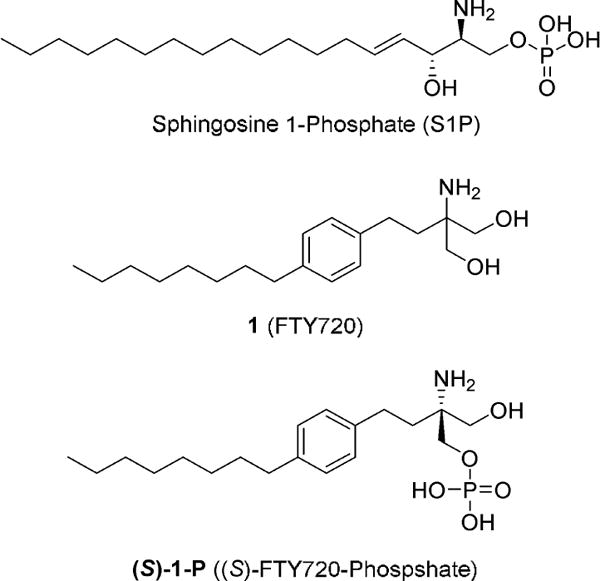

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P, Figure 1) receptors are a class of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) with five distinct subtypes, denoted as S1P1–5.1,2 These receptors are regulated by S1P and have important regulatory functions in both normal biological processes and in disease, particularly in pathological processes involving the immune system, the central nervous system (CNS), and the cardiovascular system. Because the S1P/S1P-receptor pathway is especially important in cancer and autoimmune disorders including multiple sclerosis (MS), tremendous development efforts have focused on therapeutically targeted S1P receptor ligands. These efforts discovered promising compounds, 2-amino-2-[2-(4-octyl-phenyl)-ethyl]-propane-1,3-diol 1 (FTY720, Fingolimod, Figure 1), which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of relapse remitting multiple sclerosis in 2010. Compound 1 is phosphorylated in vivo by sphingosine kinase 2; this stereospecific process generates the biologically active metabolite (S)-FTY720-Phosphate ((S)-1-P, Figure 1), a potent S1P receptor agonist.3–5 (S)-1-P is a nonselective S1P receptor ligand, which binds to each of the S1P receptor subtypes except S1P2. Since its primary mechanism of action in MS is believed to be through S1P1,4 recent development has focused on ligands having high potency and selectivity for S1P1 with suitable pharmacological properties for therapeutic applications. Although rodent studies using S1P receptor ligands suggested that adverse cardiovascular effects were the result of S1P3 agonism,6,7 the Phase I study of a S1P1 selective therapeutic reported bradycardia associated with the first dose administered to human subjects.8 Because activity at S1P3 has clear effects on the vascular system and does not appear to contribute to therapeutic efficacy of these ligands in the immune system,9 our efforts have focused on identifying subtype-selective ligands. S1P1 ligands are also being evaluated in cancer,10,11 rheumatoid arthritis,12 ulcerative colitis,13,14 as well as liver and lung injury among other therapeutic uses.15–18

Figure 1.

Structures of S1P, FTY720, and (S)-FTY720-phosphate.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a widely utilized imaging modality which can be used to noninvasively quantify molecular targets in vivo. PET is used in drug discovery to assess receptor occupancy, downstream functional changes, and impact on disease pathophysiology.19 A S1P1 specific PET tracer could greatly assist the evaluation of new therapeutics by measuring the relationship between drug exposure (dose administered or plasma concentration) and receptor occupancy, thus enabling accelerated dose selection during early clinical trials.20–22 A successful PET ligand should have a binding potency <10 nM and must be specific to the target versus neighboring nontarget tissues to allow for quantification of the regions of interest during the time frame of clinical studies (0–2 h).23,24

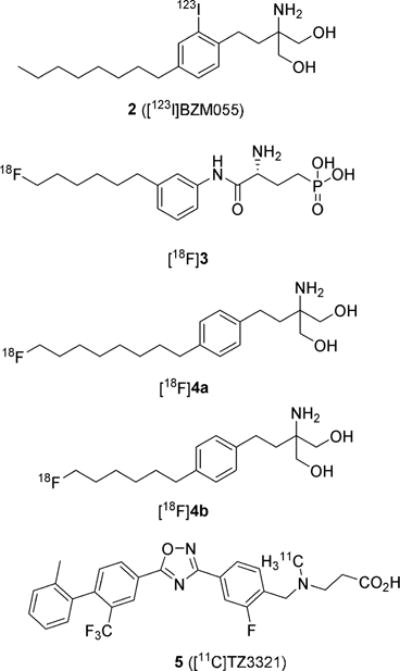

To date, no S1P receptor imaging agent suitable for clinical studies has been reported, although since 2011, several groups have reported their efforts to develop a S1P1 receptor tracer.25–27 The iodinated analogue, 2-amino-2-[2-(2-iodo-4-octylphenyl)ethyl]-1,3-propandiol 2 (BZM055, Figure 2), was 123I-labeled for single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) studies and could be 124I-labeled for PET imaging.25 Although compound 2 showed pharmacokinetic trends similar to those of compound 1, its lower rate of phosphorylation (required for receptor binding) compared to that of compound 1 limits its effectiveness as an imaging agent. The long half-lives of either iodine-123 (t1/2 = 13.2 h) or iodine-124 (t1/2 = 4.2 days) would enable the study of both the distribution kinetics of the parent ligand and its elimination kinetics. Haufe and coworkers separately reported 18F-labeled PET imaging agents based on the only known S1P1 antagonist, [(3R)-amino-4-[(3-hexylphenyl)amino]-4-oxobutyl]-phosphonic acid, mono-(trifluoroacetate) (W146),26 and based on compound 1.27 The 18F-labeled W146 analogue (R)-1-[[3-(6-fluorohexyl)-phenyl]amino-4-oxobutyl]phosphonic acid, ([18F]3, Figure 2) was shown to bind with S1P1 and unlike 1 does not require a preliminary phosphorylation step for binding potency. However, despite its in vitro stability in mouse serum, PET imaging of [18F]3 in wild-type mice showed rapid total body clearance as well as bone uptake, which is a measure of in vivo defluorination. Their recent report describes the more favorable evaluation of 18F-labeled 2 analogues, with either an 8-carbon (2-amino-2-[4-(8-fluorooctyl)phenethyl]propane-1,3-diol, [18F]4a) or a 6-carbon (2-amino-2-[4-(6-fluorohexyl)-phenethyl]propane-1,3-diol, [18F]4b) aliphatic tail (Figure 2). The ligand with the shorter tail, [18F]4b, showed reduced in vitro activity, but both tracers demonstrated uptake in S1P target organs of wild-type mice with no evidence of in vivo defluorination. Unlike [18F]3, the 1 analogues require phosphorylation before binding to S1P receptors. While potentially useful tools, at this time it is unclear how rapidly and to what extent the ligands undergo phosphorylation during the typical time frame for PET imaging (1–2 h postinjection).

Figure 2.

Structures of S1P receptor imaging agents.

We have also used the wealth of knowledge in this field to investigate PET radiotracers for S1P receptors using rodent models of human disease.28–30 Our group previously reported the radiosynthesis of the 11C-labeled S1P1 selective ligand 3-((2-fluoro-4-(5-(2′-methyl-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)benzyl)-(methyl)amino)-propanoic acid 5 ([11C]TZ3321, Figure 2) and demonstrated the feasibility of PET imaging S1P1 as a measure of inflammatory response in both the femoral artery wire-injury mouse model of restenosis29 and in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) rat model of multiple sclerosis (MS).30 Here, we present the synthesis and screening of fluorine-containing ligands based on reported compounds with either a benzoxazole core31 or an oxadiazole core.32,33 Compound 28c was identified as a potent and selective ligand for S1P1 over S1P2 or S1P3 in our competitive binding assay,34 so was 18F-labeled for biological evaluation in the mouse model of LPS-induced liver injury.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The synthetic strategy is discussed in detail below, but the two lead compounds used for development of an 18F-labeled tracer were selected due to published data indicating that they are not prodrugs which require in vivo phosphorylation and due to their favorable biological behavior.31,32 Our screening focused on S1P1 selective ligands because the efficacy of 2 in MS is attributed to its high binding potency toward to S1P1.6,35 As shown in Table 2, 28c has a high potency (IC50 = 2.63 ± 0.27 nM) and selectivity for S1P1 over S1P2 or S1P3 (IC50 > 1000 nM). The synthesis of [18F]28c was accomplished. The mouse model of LPS-induced acute liver injury was used for the in vivo evaluation of [18F]28c. Biodistribution studies were carried out with both [18F]28c and the liver imaging agent [99mTc]-N-(3-bromo-2,4,6-trimethyacetanilide) iminodiacetic acid ([99mTc]-mebrofenin) in LPS and sham mice.36 The absence of a significant difference in the liver uptake of [99mTc]mebrofenin in LPS-treated mice vs controls at 60 min postinjection suggested that the higher liver uptake of [18F]28c in LPS-treated mice compared to that of control mice was not caused by reduced hepatobiliary clearance in the liver injury model. MicroPET imaging in LPS and sham-treated mice also showed increased retention of [18F]28c in the injured liver which correlated with increased S1P1 expression observed in IHC studies, while no difference in liver uptake of [15O]water was seen between LPS-treated and sham mice,37,38 suggesting that the higher injured liver accumulation of [18F]28c is not due to a change in blood flow in the injured liver. These data indicate that a liver uptake of [18F]28c correlates well with the expression of S1P1 in mouse livers.

Table 2.

Structure–Activity Relationships in the Oxadiazole Core Series

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | Head Group (R3) | IC50 (nM) | cLogD7.4 | ||

| S1P1 | S1P2 | S1P3 | |||||

| 28a | Et | Η |

|

8.53 ± 3.14 | >1000 | >1000 | 1.10 |

| 28b | FCH2CH2 | Η |

|

9.94 ± 1.03 | >1000 | >1000 | 0.80 |

| 28c | FCH2CH2 | CF3 |

|

2.63 ± 0.27 | >1000 | >1000 | 2.32 |

| 28d | FCH2CH2 | CF3 |

|

45.4 ± 2.7 | >1000 | >1000 | 3.02 |

| 28e | FCH2CH2 | CF3 |

|

509 ± 167 | – | – | 2.08 |

| 28f | Me | CF3 |

|

103 ± 21 | – | – | 2.09 |

| 26c | FCH2CH2 | CF3 |

|

6.67 ± 0.70 | >1000 | >1000 | 4.88 |

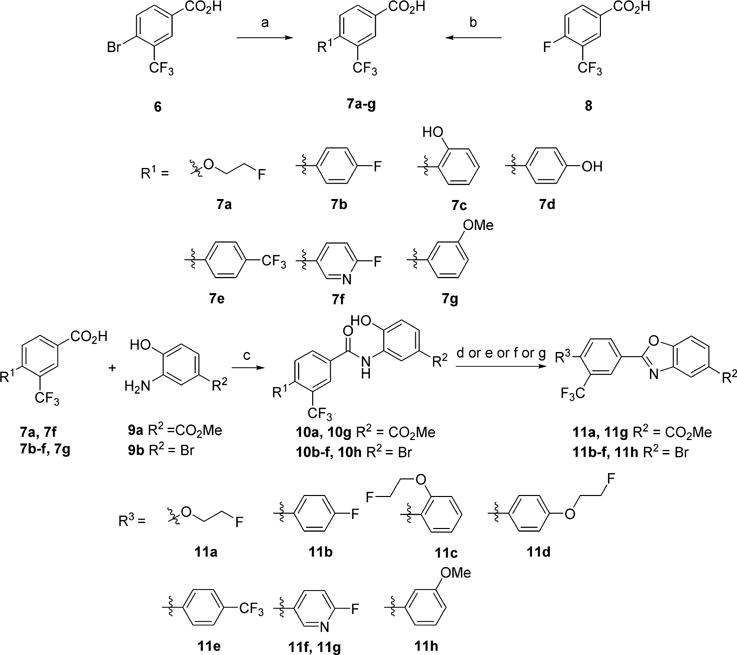

2.1. Chemistry

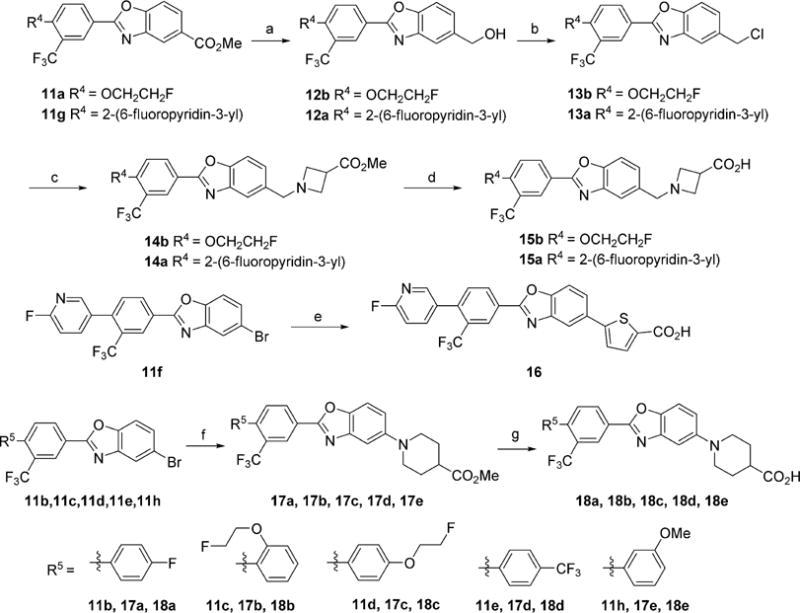

Ligands with a benzoxazole core were prepared as shown in Schemes 1 and 2. The starting halogenated trifluoromethylbenzoic acids were functionalized by either palladium catalyzed Suzuki coupling with the desired aryl boronic acid to provide the biaryl moieties or by nucleophilic aromatic substitution with the desired alcohol to give the ethereal products. The appendant carboxylic acid was transformed to the corresponding acid chloride with oxalyl chloride and catalytic DMF, which was then reacted with a functionalized 2-hydroxyaniline under Schotten–Baumann conditions to give amides 10. These amides were subsequently heated under acidic conditions to cyclize and provide the benzoxazole cores. The installation of the polar head groups was accomplished by a variety of methods. β-Amino acids 15a and 15b, were prepared by reduction of a methyl ester to an alcohol and functional group transformation to a chloride, and subsequently to the azetidine ester, which was unmasked to provide 15. Acid 16 was prepared by a Suzuki coupling with a thiophene boronic acid. Palladium-catalyzed amination with methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate gave the protected products, which were subsequently saponified to give acids 18.

Scheme 1. Preparation of Benzoxazole Coresa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Pd(OAc)2, SPhos, CsF, R1B(OH)2, 1,4-dioxane/H2O for 7b–g; (b) NaH, R1OH, DMSO for 7a; (c) (i) (COCl)2, cat. DMF, CH2Cl2; (ii) Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2; (d) p-TsOH, toluene for 11a, 11b, 11e, 11h; (e) (i) p-TsOH, toluene; (ii) Cs2CO3, fluoroethyltosylate, DMF for 11c, 11d; (f) Ph3P, DIAD, THF for 11f; (g) PPTS, toluene for 11g.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Benzoxazole Targetsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DIBAI-H, THF; (b) cyanuric chloride, DMF, CH2Cl2; (c) methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride, i-Pr2NEt, MeCN; (d) LiOH, THF/H2O; (e) Pd(OAc)2, SPhos, KF, 2-carboxythiophene-5-boronic acid, 1,4-Dioxane/H2O; (f) Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3, XPhos, NaOtBu, methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate; (g) LiOH, THF/H2O.

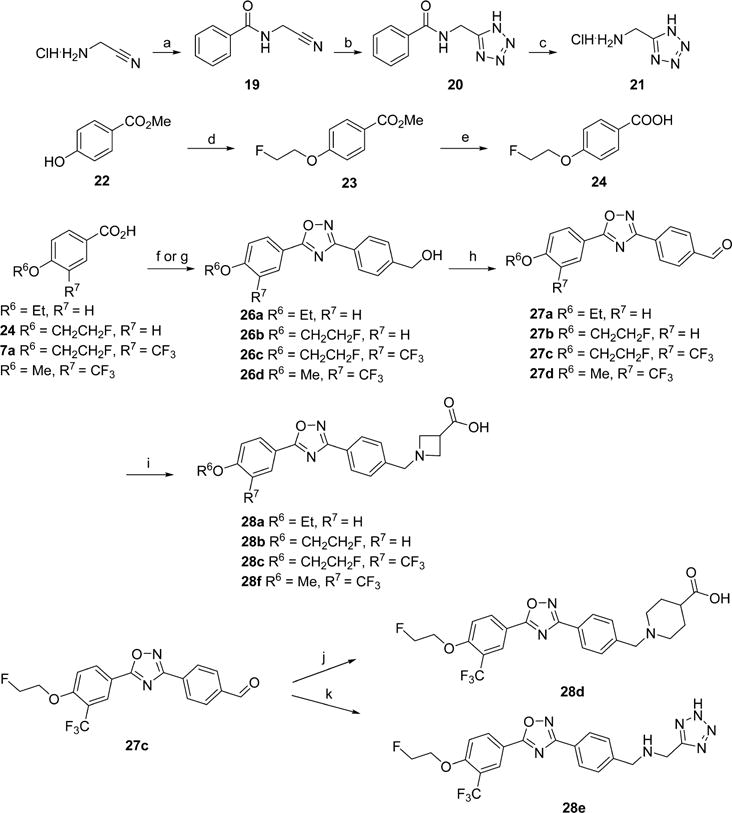

Ligands with an oxadiazole core were synthesized according to Scheme 3. The required carboxylic acids were prepared as described above or from methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (22) by alkylation and saponification. The desired carboxylic acid was reacted with N′-hydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)benzimidamide (25) under standard peptide coupling conditions, and subsequently thermally cyclized to give the oxadiazole cores. O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU) was also used as a coupling agent, followed by thermal cyclization.39 The appendant benzyl alcohol was oxidized under Swern conditions to give aldehydes 27. The β-amino acid headgroup was affixed by reductive amination with the desired amine to provide the targeted ligands 28a–f. The lipophilicity of a radiotracer, expressed as logP, impacts nonspecific binding and its ability to cross the BBB, which is a key physical constraint for targets in the CNS and intracellular targets including enzymes.40 The calculated lipophilicity at a pH of 7.4 of the new compounds is reported as cLogD values in Tables 1 and 2. The oxadiazole 28c had a cLogD of 2.32 which is within the desired range for CNS tracers and, as discussed below, a favorable in vitro binding profile; thus, we elected to pursue its development as a radiotracer and synthesized precursors for radiolabeling. Precursor 32 for radiolabeling using [18F]2-fluoroethyltosylate was prepared from phenol 29, as shown in Scheme 4, using a synthetic route similar to that used for the oxadiazole analogues. Formation of the oxadiazole proceeded as expected; however, the oxidation step required different conditions due to the presence of the unprotected phenol. Oxidation with manganese(IV) oxide provided smooth conversion to the desired aldehyde 31. Reductive amination under buffered conditions afforded 32. Precursor 34 for direct labeling was also prepared as shown in Scheme 5. Starting with aldehyde 31, the free phenol was alkylated with ethylene ditosylate to provide compound 33, which was subjected to reductive amination to yield 34. The reductive amination conditions were modified to utilize sodium triacetoxyborohydride because harsher reducing agents tended to reduce the alkyl tosylate.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Benzoxazole Targetsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DIBAI-H, THF; (b) cyanuric chloride, DMF, CH2Cl2; (c) methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride, i-Pr2NEt, MeCN; (d) LiOH, THF/H2O; (e) Pd(OAc)2, SPhos, KF, 2-carboxythiophene-5-boronic acid, 1,4-dioxane/H2O; (f) Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3, XPhos, NaOtBu, methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate; (g) LiOH, THF/H2O.

Table 1.

Structure–Activity Relationships in the Benzoxazole Core Series

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | S1P1 IC50 (nM) | S1P1 EC50 (nM) | cLogD7.4 |

| 15a |

|

|

92.7 ± 35.3 | – | 2.08 |

| 15b |

|

|

76.4 ± 21.6 | – | 2.21 |

| 16 |

|

|

334 ± 59 | 2.99 | 4.10 |

| 18a |

|

|

486 ± 69 | 0.76 | 3.72 |

| 18b |

|

|

894 ± 367 | 3.04 | 3.69 |

| 18c |

|

|

114 ± 73 | 11.1 | 3.84 |

| 18d |

|

|

498 ± 335 | 4.47 | 4.76 |

| 18e |

|

|

95.7 ± 25.1 | 4.90 | 3.56 |

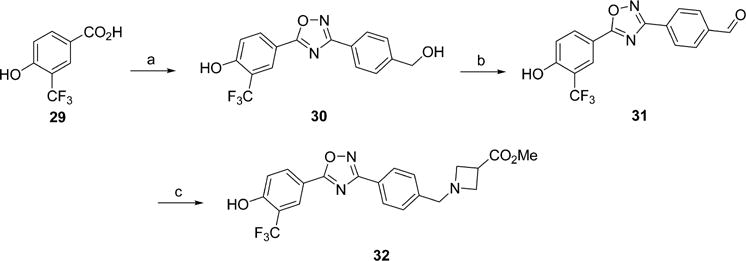

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Radiolabeling Precursor 32a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) TBTU, HOBt, 25, DMF; (b) MnO2, 1,4-dioxane (c) methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride, NaBH3CN, AcOH, DIPEA, MeOH.

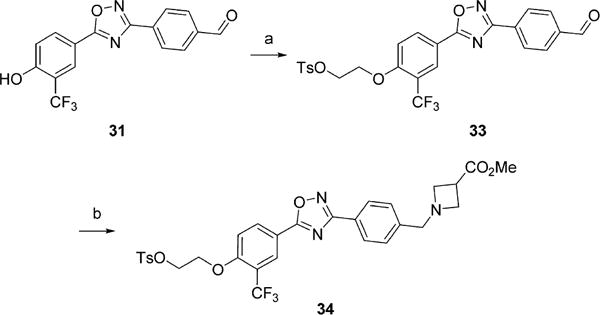

Scheme 5. Preparation of Direct Radiolabeling Precursor 34a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (CH2OTs)2, K2CO3, MeCN; (b) (i) DIPEA, 1,2-DCE/MeOH; (ii) NaBH(OAc)3, AcOH, 1,2-DCE.

2.2. In Vitro Binding Assays

Competitive inhibition of the binding of radiolabeled [32P]S1P to the new analogues was measured to determine the affinity of the ligands for S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3.34 The results are reported in Tables 1 and 2. The benzoxazole series of ligands displayed nanomolar activity in the functional assay (EC50); however, the ligands displayed lower IC50 value for S1P1 in the competitive binding assay (IC50). Although the reason for this discrepancy in the assay results is not clear, similar results have been observed with other S1P receptor ligands.41 Additionally, while functional assays can be extremely useful in the preliminary stages of imaging agent development, the binding potency of a ligand cannot be determined without a competitive binding assay.42 While none of the ligands in this series had sufficient binding affinity (IC50 < 10 nM) to be pursued as a PET tracer, structure–activity relationships (SAR) became apparent. The residues and shape of the S1P1 binding pocket have been well documented with a published crystal structure.43 The binding pocket consists of two major components, a charged head portion and a lipophilic tail area. The strong recognition for ligand binding is thought to be derived from interactions between the positively charged Arg120 and the phosphate in S1P, and interactions between the negatively charged Glu121 and the ammonium in S1P. The lipophilic part of the binding pocket appears to be quite tolerant of a variety of functional groups, with the noted exception of the ortho-substituted fluoroethyl ether 18b (IC50 = 894 ± 367 nM).

The oxadiazole ligand series showed much more promise than the benzoxazole series, as seen in Table 2. We explored the effects of modifying the lipophilic side chain of 28a (IC50 = 8.53 ± 3.14 nM). Addition of a fluorine (28b, IC50 = 9.94 ± 1.03 nM) had no significant change on the binding potency, while an ortho-trifluoromethyl group noticeably improved the affinity to 2.63 ± 0.27 nM (28c). Next, we turned to the polar headgroup. While some S1P1 ligands without a polar headgroup have a high degree of potency, we elected to maintain this property in our explorations. Changing the azetidine ring of 28c to a piperidine (28d) gave a 20-fold decrease in binding affinity to 45.4 ± 2.7 nM. Bioisosteric substitution of the acid to a tetrazole resulted in significant loss of activity of over 100-fold to 509 ± 167 nM (28e), while shortening the two-carbon tail to a methyl group adversely impacted the binding potency giving an IC50 > 100 nM (28f). Finally, the benzyl alcohol 26c was synthesized to determine how critical the amino acid headgroup was; surprisingly, this headgroup was not required as 26c was quite potent with an IC50 of 6.67 ± 0.70 nM. All compounds with a IC50 value under 50 nM were screened for selectivity versus S1P2 and S1P3; no tested compounds showed detectable binding with S1P2 or S1P3. 28c had a high potency for S1P1 (IC50 = 2.63 ± 0.27 nM) with no measurable potency for S1P2 (IC50 > 1000 nM) or S1P3 (IC50 > 1000 nM) with a cLogD of 2.32; thus, we elected to pursue 28c as our lead compound for 18F-labeling.

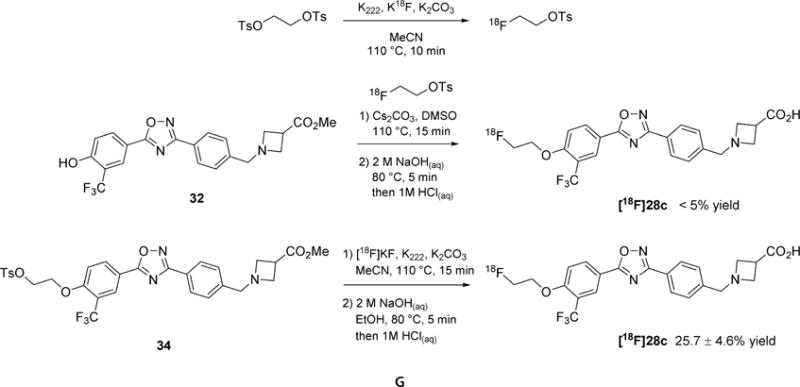

2.3. Radiochemistry

The radiosynthesis of 28c was initially attempted using the versatile indirect approach of labeling with [18F]2-fluoroethyltosylate. The precursor 32 was prepared as shown in Scheme 4. Unfortunately, attempts to label 32 indirectly resulted only in extremely low yields under a variety of conditions (<5% radiochemical yield for the alkylation step), likely due to the low nucleophilicity of the electron-deficient phenol. Because of this concern, as well as a desire to avoid a three-step, two-pot radiosynthesis, we subsequently pursued a direct labeling approach starting with the tosylate precursor (34) as shown in Scheme 6.

Scheme 6.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]28c

The tosylate precursor (34) was reacted with Kryptofix 222 (K222) and [18F]KF in acetonitrile for 15 min at 110 °C to install the fluoroethyl tail. The carboxylic acid headgroup was unmasked by saponification with sodium hydroxide. The resulting crude product was purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to give [18F]28c in 25.7 ± 4.6% (n = 10, decay corrected to start of synthesis), with >98% chemical and radiochemical purity, and a high specific activity (1.43 ± 0.12 Ci/μmol).

2.4. Biological Studies

2.4.1. Biodistribution in Normal Rats

To investigate the tissue distribution of [18F]28c in living subjects, a biodistribution study was performed in adult male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats. As shown in Table 3, the results showed significant uptake and retention in the liver, without evidence of in vivo defluorination (no increased accumulation in bone was observed from 5 to 120 min postinjection). Relatively high uptake was observed for the heart, lungs, pancreas, and spleen, all organs known to have high S1P1 expression. The surprisingly low brain uptake of [18F]28c as shown in Table 3 may potential limit its utility for CNS applications.

Table 3.

Biodistribution of [18F]28c in Adult Male SD Rats (% ID/g ± SD)(n = 4)

| organ | 5 min | 30 min | 60 min | 120 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blood | 0.304 ± 0.058 | 0.240 ± 0.024 | 0.223 ± 0.007 | 0.178 ± 0.039 |

| lung | 0.753 ± 0.097 | 0.413 ± 0.005 | 0.341 ± 0.024 | 0.272 ± 0.053 |

| liver | 6.076 ± 1.134 | 5.509 ± 0.567 | 5.081 ± 0.324 | 3.355 ± 0.772 |

| spleen | 0.589 ± 0.067 | 0.282 ± 0.030 | 0.251 ± 0.014 | 0.202 ± 0.033 |

| kidney | 2.026 ± 0.250 | 1.080 ± 0.000 | 1.117 ± 0.052 | 0.845 ± 0.091 |

| muscle | 0.121 ± 0.013 | 0.145 ± 0.013 | 0.156 ± 0.010 | 0.135 ± 0.007 |

| fat | 0.051 ± 0.011 | 0.061 ± 0.003 | 0.051 ± 0.003 | 0.059 ± 0.011 |

| heart | 0.811 ± 0.167 | 0.445 ± 0.030 | 0.379 ± 0.015 | 0.316 ± 0.061 |

| brain | 0.027 ± 0.004 | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.015 ± 0.002 |

| bone | 0.215 ± 0.027 | 0.114 ± 0.002 | 0.105 ± 0.100 | 0.100 ± 0.012 |

| pancreas | 0.755 ± 0.207 | 0.320 ± 0.047 | 0.298 ± 0.089 | 0.265 ± 0.128 |

| thymus | 0.150 ± 0.023 | 0.151 ± 0.010 | 0.161 ± 0.007 | 0.182 ± 0.013 |

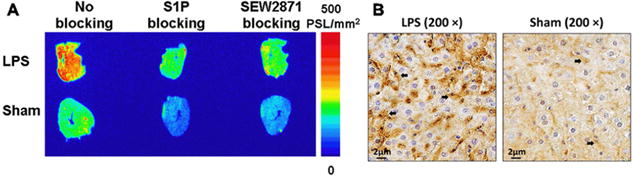

2.4.2. In Vitro Autoradiography and IHC in LPS-Treated Mice

We utilized the mouse model of LPS-induced liver injury and inflammation, in which inflammation caused by LPS is known to cause increased liver expression of S1P1 after ∼24 h to evaluate [18F]28c in tissue from an animal model of inflammatory disease.44,45 In vitro autoradiographic data showed increased uptake of [18F]28c in the liver of LPS-treated mice, compared with the sham liver shown in Figure 3A. The specificity of [18F]28c for S1P1 was demonstrated by incubation of adjacent mouse liver slices with the tracer in the presence of either the native ligand (S1P) or the S1P1 selective compound, SEW2871.46 The upregulation of S1P1 in the liver at the 24 h time point following LPS treatment was further confirmed by IHC staining as shown in Figure 3B. These blocking studies in conjunction with the IHC results suggest that the binding of [18F]28c in the liver of LPS-treated mice is the result of specific binding to the receptor and is increased when S1P1 expression is increased.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative in vitro autoradiographic images of serial liver sections from LPS-treated and sham mice after incubation with [18F]28c under baseline or blocking conditions. (B) IHC staining for S1P1 in mouse liver sections. Positive staining for S1P1 (brown, indicated by black arrows) was observed in the liver of both LPS-treated (left) and sham (right) mice. The number of S1P1-positive cells in the liver of LPS-treated mice was much greater than that in sham mice.

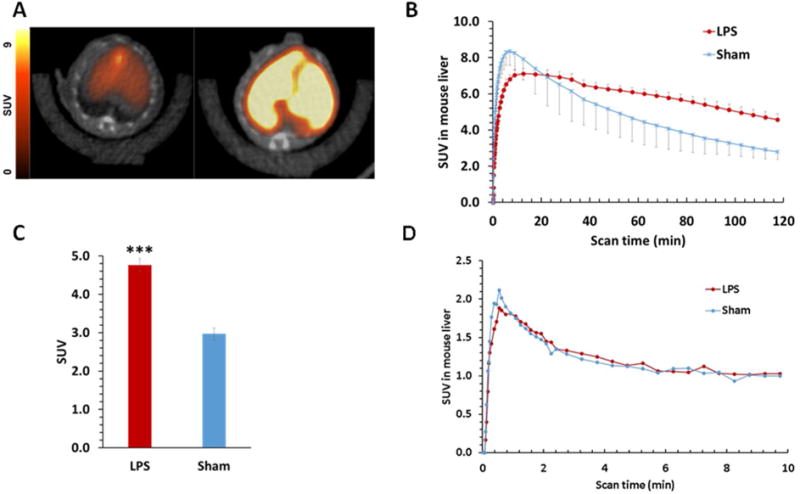

2.4.3. MicroPET Imaging of LPS-Treated Mice with [18F]28c and [15O]Water

Subsequent microPET imaging in the LPS model of liver inflammation also clearly showed increased accumulation of [18F]28c in the liver of LPS-treated mice compared to that in sham controls (Figure 4A). Time–activity curves (TAC) confirmed higher tracer uptake in the liver of LPS pretreated mice compared with that in the sham controls (Figure 4B). Quantification of the liver region of interest (ROI) in the microPET scan from 100 to 120 min shows a 61% increase (P < 0.001, n = 4) (Figure 4C). These results were confirmed by euthanasia of the mice post-PET for an acute biodistribution study. The liver uptake of [18F]28c in the LPS-treated mouse at 2 h was 1.95-fold higher than that in the sham mice (12.5 vs 24.4% ID/gram, P < 0.001, n = 4). To further demonstrate that the increased uptake of [18F]28c in the liver was not attributed to changes in blood flow in the LPS-induced model of liver injury, additional microPET studies were performed with an injection of [15O]water 30 min prior to the injection of [18F]28c. [15O]Water is a widely used radiotracer for assessing blood flow.47,48 As shown in Figure 4D, the liver TAC for [15O]water in LPS-treated mice showed no significant change compared to that in the sham mice. This suggested that the increase in vivo uptake of [18F]28c in the liver of LPS-treated mice is the result of increased S1P1 expression and not increased blood flow.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative summed 120 min transverse PET/CT images of [18F]28c in a sham (left) and LPS-treated (right) mouse. (B) Liver time–activity curves (TAC) of [18F]28c standardized uptake values (SUV) in sham and LPS-treated mice. (C) Sham vs LPS-treated summed liver SUVs from 100 to 120 min postinjection. P < 0.001. (D) Liver TACs of [15O]H2O in sham and LPS-treated mice.

2.4.4. Biodistribution of [18F]28c and [99mTc]Mebrofenin in LPS-Treated Mice

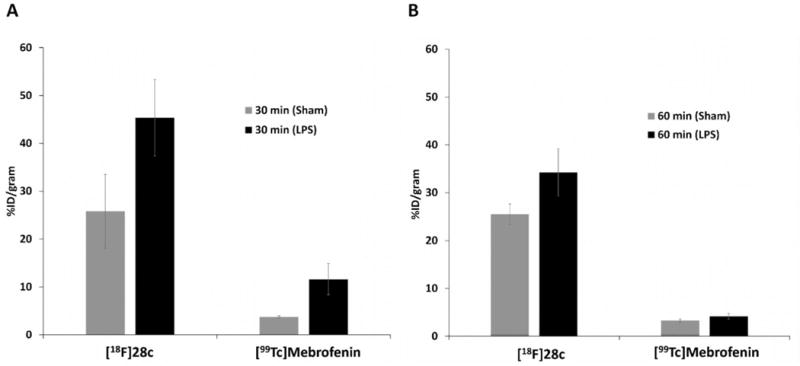

To confirm that the uptake of [18F]28c was associated with S1P1 expression, we utilized a mouse model of LPS-induced liver injury and inflammation, in which inflammation caused by LPS is known to cause increased liver expression of S1P1 after ∼24 h.44,45 Biodistribution studies comparing [18F]28c uptake in saline-treated sham controls vs the LPS-treated mouse model demonstrated a large increase in liver uptake (Figure 5). In order to demonstrate that tracer retention in the liver was not due to impaired hepatobiliary clearance in the liver injury model, an additional study was carried out with this model using a liver imaging agent. [99mTc]Mebrofenin is used to detect if the hepatobiliary transport is impaired. Increased liver uptake of [99mTc]-mebrofenin indicates the potential for nonspecific retention of drugs (in this case, [18F]28c) in the liver due to impaired clearance, rather than uptake specific to the pathological increase in S1P1 at the molecular level.36,49,50,32,33 We hypothesized that increased liver uptake of [99mTc]mebrofenin in LPS-treated mice versus the sham control mice at 60 min would suggest that increased uptake of the S1P1 tracer resulted from a severely damaged liver; however, if the liver uptake of [99mTc]mebrofenin in LPS-treated mice versus the sham mice was similar at 60 min (as we observed), the increase should reflect an increase in S1P1 rather than impaired clearance.36,49 To confirm that this increase in uptake of [18F]28c resulted from the increase expression of S1P1 receptor response to liver injury, the biodistribution study of [99mTc]mebrofenin was performed in the LPS-induced liver injury models. Although increased [99mTc]mebrofenin was observed in the liver of LPS-treated mice at 30 min p.i. compared with sham mice, at 60 min p.i. there was no significant difference between the sham and LPS study groups. The uptake of [18F]28c showed a significant increase in the LPS-treated mice compared to that of the sham control mice at both 30 and 60 min (Figure 5). The biodistribution data demonstrated that the increased hepatobiliary uptake of [18F]28c in LPS-treated mice is mainly caused by the upregulation of S1P1 expression in the liver.

Figure 5.

Liver uptake in LPS-treated and sham mice 30 min (A) and 60 min (B) postinjection of [18F]28c or [99mTc]mebrofenin.

3. CONCLUSIONS

We synthesized 14 fluorine-containing analogues based on two lead pharmacophores and determined their affinity for S1P1. Potent compounds (IC50 < 50 nM for S1P1) were subsequently screened for their S1P2 and S1P3 binding affinities. Seven compounds were found to have IC50 values <100 nM, while three were very potent with S1P1 IC50 values <10 nM. We explored the SAR studies on the oxadiazole containing pharmacophore by optimizing the lipophilic tail binding portion of the binding pocket. The oxadiazole 28c had a high potency (2.63 nM for S1P1) and selectivity (>100-fold for S1P1 versus S1P2/3), and was successfully radiolabeled in high yield and high specific activity. Biodistribution in normal rats showed no evidence of defluorination, so the mouse model of liver inflammation was used for subsequent biological evaluation of [18F]28c as a PET tracer for imaging S1P1. In vitro autoradiography and microPET imaging studies showed increased binding in vitro and in vivo retention of [18F]28c in the liver of LPS-treated vs control mice. IHC staining studies confirmed that S1P1 expression was increased in the liver of LPS-treated mice. Additional microPET imaging showed no difference in liver uptake of [15O]water between LPS-treated and control mice,37,38 further supporting the hypothesis that the higher uptake and retention of [18F]28c in the liver of LPS-treated mice was a reflection of increased S1P1 due to inflammation and not due to a change in blood flow. Parallel acute biodistribution studies in the LPS model were carried out with both [18F]28c and the liver imaging agent [99mTc]-mebrofenin.36 The absence of a significant difference in liver uptake of [99mTc]mebrofenin in LPS-treated vs control liver uptake 60 min postinjection suggested that the increased liver uptake of [18F]28c observed in the PET studies of LPS-treated mice was not the result of reduced hepatobiliary clearance due to liver injury. Together, these data indicate that uptake of [18F] 28c reflects the expression of S1P1 and suggest that [18F]28c is a S1P1 specific radiotracer with potential for use in quantifying S1P1 receptor expression in response to inflammation.

4. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

4.1. Chemistry Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise indicated, all reactions were conducted in oven-dried (140 °C) glassware. Stainless steel syringes or cannulae that had been oven-dried (140 °C) and cooled under a nitrogen atmosphere or in a desiccator were used to transfer air- and moisture-sensitive liquids. Yields refer to chromatographically and spectroscopically (1H NMR) homogeneous materials, unless otherwise stated. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) carried out on precoated glass plates of silica gel (0.25 mm) 60 F254 from EMD Chemicals Inc. Visualization was accomplished with ultraviolet light (UV 254 nm) or by shaking the plate in a sealed jar containing silica gel and iodine. Alternatively, plates were treated with one of the following solutions (this was accomplished by holding the edge of the TLC plate with forceps or tweezers and immersing the plate into a wide-mouth jar containing the desired staining solution) and carefully heating with a hot-air gun (450 °C) for approximately 1–2 min (note: excess stain was removed by resting the TLC on a paper towel prior to heating): 10% phosphomolybdic acid in ethanol, 1% potassium permanganate/7% potassium carbonate/0.5% sodium hydroxide aqueous solution, and/or anisaldehyde in ethanol with 10% sulfuric acid. Flash column chromatography was performed using Silia Flash P60 silica gel (40–63 μm) from Silicycle. All workup and purification procedures were carried out with reagent grade solvents in air.

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400 MHz instrument. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) and are calibrated using residual undeuterated solvent as an internal reference (CDCl3, δ 7.26 ppm; MeOD-d4, δ 3.31 ppm; DMSO-d6, δ 2.50 ppm). Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity, coupling constants (Hz), and integration. The following abbreviations or combinations thereof were used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, pent = pentet, sext = sextet, sept = septet, m = multiplet, at = apparent triplet, aq = apparent quartet, and b = broad. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian instrument (100 MHz) spectrometer with complete proton decoupling. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm and are calibrated using a residual undeuterated solvent as an internal reference (CDCl3, δ 77.16 ppm; MeOD-d4, 49.00 ppm; and DMSO-d6, 39.52 ppm). Elemental compositions (C, H, and N) are within ±0.4% of the calculated values and were determined by Atlantic Microlab, Inc. Lipophilicity values as cLogD are reported as the calculated Log P value at pH 7.4 and were obtained using ACD/I-Lab version 7.0 (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc. Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The biological activity of all of the final compounds was determined by an analytical HPLC method with purity ≥ 95%.

4.1.1. Synthesis. General Procedure A: Suzuki Coupling

To an oven-dried round-bottomeded flask equipped with a stir bar was added Pd(OAc)2 (2 mol %), 2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl (SPhos, 5 mol %), commercially available 4-bromo-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid (6) (1 equiv), the boronic acid (1.1 equiv), and a fluoride base (3 equiv). 1,4-Dioxane (0.37 M) and degassed H2O (0.37 M) were added to the reaction mixture, and the reaction was degassed by sparging with N2(g) for 10 min, at which time it was equipped with a condenser and placed in a preheated 110 °C oil-bath. The reaction mixture was stirred for the time indicated, cooled to room temperature (r.t.), and poured into a 1:1 mixture of ethyl acetate and 1 N HCl (aq). The quenched reaction mixture was stirred for 20 min, and the layers were then separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (×2). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4, concentrated in vacuo, and purified as specified.

General Experimental B: Amide Formation

To an oven-dried round-bottomeded flask equipped with a stir bar was added carboxylic acid (1 equiv) followed by CH2Cl2 (0.1 M). Five drops of N,N-dimethylformamide was added via pipet followed by the slow addition of oxalyl chloride (2.3 equiv) via a syringe. The reaction was then stirred at r.t. for 2 h, at which time it was concentrated in vacuo. The crude acid chloride was then dissolved in toluene (0.15 M), and 10% NaHCO3(aq) (0.3 M) was added. The aniline 9a or commercially available 2-amino-4-bromophenol (9b) (1 equiv) was added, and the reaction was stirred overnight. Upon completion of the reaction, the resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with H2O, toluene, and hexanes to give the desired amide.

General Experimental C: Benzoxazole Formation

To a round-bottomeded flask equipped with a stir bar was added the amide (1 equiv), toluene (0.1 M), and p-toluenesulfonic acid (2.1 equiv) or pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (2.1 equiv). The reaction was equipped with a reflux condenser and lowered into a preheated 130 °C oil-bath. The reaction mixture was stirred for the specified time, cooled to r.t., diluted with EtOAc, and washed with sat. NaHCO3(aq) (×2), and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo to give the desired benzoxazole.

General Procedure D: Buchwald–Hartwig Coupling

To an oven-dried flask (pressure-vessel or Schlenk tube) equipped with a stir bar was added Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (2 mol %), XPhos (8 mol %), sodium tert-butoxide (1.4 equiv), and the aryl bromide (1 equiv). Toluene (0.5 M) was added followed by the amine (1.2 equiv), and the reaction mixture was degassed by sparging with N2(g) for 10 min. The reaction vessel was sealed with a Teflon screw-cap and lowered into a preheated 110 °C oil-bath. After 18–20 h, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to r.t. and diluted with ethyl acetate. The reaction mixture was then concentrated in vacuo and purified as specified.

General Procedure E: Saponification

To a 16 × 150 mm test tube equipped with a stir bar was added the ester (1 equiv), THF (0.24 M), H2O (1.2 M), and lithium hydroxide (2 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 16–18 h, at which time it was acidified to pH 1 with 1 M HCl(aq). The reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (×4). The combined organic layers were washed with brine and concentrated in vacuo to give the desired products.

General Procedure F: Oxadiazole Formation

To an oven-dried round-bottomeded flask equipped with a stir bar was added the acid (1 equiv), EDC·HCl (1 equiv), HOBt (1 equiv), and DMF (0.8 M). The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 30 min, at which time amidoxime (1 equiv) was added. A reflux condenser was attached, and the reaction vessel was placed in a preheated 120–140 °C oil-bath and stirred overnight (14–18 h). The reaction mixture was cooled to r.t. and diluted with EtOAc and water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×1). The combined organic layers were washed with water, 1 M HCl(aq), water, and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give the desired product.

General Procedure G: Reductive Amination

To a round-bottomeded flask equipped with a stir bar was added aldehyde (1 equiv), amine (1.05 equiv), methanol (0.07 M), and acetic acid (2 M). The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at which time sodium cyanoborohydride (0.5 equiv) was added as a solution in methanol (0.25 M). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1–2 h, at which time the solids were filtered and washed with methanol to give the desired product.

4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic Acid (7a)

To an oven-dried 500 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added 4-fluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid (8)(8.32 g, 40.0 mmol), 100 mL of DMSO, and 2-fluoroethanol (3.52 mL, 60.0 mmol). Sodium hydride (3.60 g, 90.0 mmol) was added portionwise, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 16 h. The reaction mixture was poured into water and acidified with 12 M HCl(aq) to pH 1. The resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with water and hexanes to give a tan solid (9.8 g, 97% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 12.18 (s, 1H), 8.18 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.85–4.40 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 166.0, 159.44, 135.6, 128.0 (q, JC–F = 4.9 Hz), 123.2 (q, JC–F = 274 Hz), 123.2, 117.4 (q, JC–F = 31.1 Hz), 113.9, 81.8 (d, JC–F = 168 Hz), 68.6 (d, JC–F = 19.1 Hz), MP: 131–133 °C. HRMS (EI-TOF) m/z calcd for C10H7F4O3 [M – H] 251.0337. Found [M – H] 251.0289.

4′-Fluoro-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic Acid (7b)

Following general experimental procedure A, Pd(OAc)2 (67 mg, 0.30 mmol), SPhos (306 mg, 0.75 mmol), 6 (4.0 g, 14.9 mmol), 4-fluorophenylboronic acid (2.29 g, 16.4 mmol), cesium fluoride (6.79 g, 44.7 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (40 mL), and degassed H2O (40 mL) were combined. The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h, to give 3.0 g of a tan solid which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 13.56 (br s, 1H), 8.28 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.43–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.29 (m, 2H).

2′-Hydroxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic Acid (7c)

Following general experimental procedure A, Pd(OAc)2 (84 mg, 0.37 mmol), SPhos (382 mg, 0.93 mmol), 6 (5.0 g, 18.6 mmol), 2-hydroxyphenylboronic acid (2.82 g, 20.4 mmol), cesium fluoride (8.48 g, 55.8 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (50 mL), and degassed H2O (50 mL) were combined. The reaction mixture was stirred for 20 h and purified on a silica gel column, eluting with 5% MeOH/CH2Cl2, to provide 5.2 g of a yellow semisolid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.54 (s, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (td, J = 8.8 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H).

4′-Hydroxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic Acid (7d)

Following general experimental procedure A, Pd(OAc)2 (67 mg, 0.30 mmol), SPhos (306 mg, 0.75 mmol), 6 (4.0 g, 14.9 mmol), 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid (2.46 g, 17.8 mmol), cesium fluoride (6.79 g, 44.7 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (40 mL), and degassed H2O (40 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 20 h and purified on a silica gel column, eluting with 5% MeOH/CH2Cl2, to provide 4.2 g of a yellow semisolid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.73 (s, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.83(d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H).

2,4′-Bis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic Acid (7e)

Following general experimental procedure A, Pd(OAc)2 (42 mg, 0.19 mmol), SPhos (191 mg, 0.47 mmol), 6 (2.5 g, 9.3 mmol), 4-(trifluorofluoromethyl)phenylboronic acid (2.12 g, 11.2 mmol), potassium fluoride (4.24 g, 27.9 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (25 mL), and degassed H2O (25 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 22 h to give 2.35 g of a yellow solid, which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 12.67 (br s, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H).

4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic Acid (7f)

Following general experimental procedure A, Pd(OAc)2 (50 mg, 0.22 mmol), SPhos (230 mg, 0.56 mmol), 6 (3.0 g, 11.15 mmol), (6-fluoropyridin-3-yl)boronic acid (1.89 g, 13.4 mmol), cesium fluoride (5.08 g, 33.5 mmol), 30 mL of 1,4-dioxane, and 30 mL of degassed H2O. The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h to give a yellow solid, which was used without further purification (3.0 g, 94% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 13.63 (br s, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.30–8.24 (m, 2H), 8.09–7.98 (m, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.34 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.8 Hz, 1H).

3′-Methoxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic Acid (7g)

Following general experimental procedure A, Pd(OAc)2 (50 mg, 0.22 mmol), SPhos (230 mg, 0.56 mmol), 6 (3.0 g, 11.15 mmol), 3-methoxyphenylboronic acid (2.04 g, 13.4 mmol), cesium fluoride (5.08 g, 33.5 mmol), 30 mL of 1,4-dioxane, and 30 mL of degassed H2O. The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h, to give a yellow solid, which was used without further purification (3.12 g, 95% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 13.22 (br s, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.06–7.01 (m, 1H), 6.93–6.86 (m, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H).

Methyl 3-amino-4-hydroxybenzoate (9a)

To a 250 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added methyl 4-hydroxy-3-nitrobenzoate (5.0 g, 25.4 mmol), 120 mL of EtOH, and 540 mg of 10% Pd/C. One balloon of H2(g) was bubbled through the reaction mixture, and then it was stirred under 1 atm of H2(g) overnight (16 h). At this time, the reaction was filtered through a Celite plug, washing with EtOH, and concentrated in vacuo to give a brown solid (4.17 g, 98% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 7.45 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H).

Methyl 3-(4-(2-fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzamido)-4-hydroxybenzoate (10a)

To an oven-dried 100 mL of round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added acid 7a (2.50 g, 9.91 mmol), 50 mL of CH2Cl2, and 10 drops of DMF. Oxalyl chloride (1.68 mL, 19.8 mmol) was added carefully, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at r.t. The reaction was concentrated in vacuo and dissolved in 33 mL of CH2Cl2. Triethylamine (5.52 mL, 39.6 mmol) was added followed by DMAP (120 mg, 0.99 mmol) and aniline 9a (1.66 g, 9.91 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight and diluted with MTBE, at which point a precipitate had formed. The precipitate was filtered, washed with MTBE, and hexanes to give a white solid which was used in the next step without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 10.75 (br s, 1H), 9.83 (s, 1H), 8.27 (app q, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 8.23 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.87–4.68 (m, 2H), 4.57–4.42 (m, 2H).

N-(5-Bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)-4′-fluoro-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxamide (10b)

Following general experimental procedure B, carboxylic acid 7b (720 mg, 2.53 mmol), 25.3 mL of CH2Cl2, oxalyl chloride (0.49 mL, 5.82 mmol), 17 mL of toluene, 8.5 mL of 10% NaHCO3(aq), and 9b (476 mg, 2.53 mmol) were combined to give amide 10b as a tan solid (1.11 g, 99% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 8.30 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.25 (m, 4H), 7.08 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H).

N-(5-Bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)-2′-hydroxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxamide (10c)

Following general experimental procedure B, carboxylic acid 7c (3.5 g, 12.4 mmol), 124 mL of CH2Cl2, oxalyl chloride (2.41 mL, 28.5 mmol), 82 mL of toluene, 41 mL of 10% NaHCO3(aq), and 9b (2.33 g, 12.4 mmol) were combined to give amide 10c as a brown solid (1.15 g, 20% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 8.32 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 2H), 7.05 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.89–6.82 (m, 2H).

N-(5-Bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)-4′-hydroxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxamide (10d)

Following general experimental procedure B, carboxylic acid 7d (4.2 g, 14.9 mmol), 149 mL of CH2Cl2, oxalyl chloride (2.90 mL, 34.3 mmol), 100 mL of toluene, 50 mL of 10% NaHCO3(aq), and 9b (2.80 g, 14.9 mmol) were combined to give amide 10d as a brown solid which was used in the next step without further purification (3.4 g, 50% yield).

N-(5-Bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)-2,4′-bis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxamide (10e)

Following general experimental procedure B, acid 7e (2.27 g, 6.79 mmol), 68 mL of CH2Cl2, oxalyl chloride (1.21 mL, 14.3 mmol), 46 mL toluene, 23 mL of 10% NaHCO3(aq), and 9b (1.28 g, 6.79 mmol) were combined to give a light brown solid (2.81 g, 82% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 10.09 (br s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.92–7.84 (m, 3H), 7.65–7.56 (m, 3H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H).

N-(5-Bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(6-fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (10f)

Following general experimental procedure B, acid 7f (1.00 g, 3.51 mmol), 35 mL of CH2Cl2, oxalyl chloride (0.68 mL, 8.1 mmol), 24 mL of toluene, 12 mL of 10% NaHCO3(aq), and 9b (660 mg, 3.51 mmol) were combined to give a tan solid (1.0 g, 63% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 10.32 (br s, 1H), 8.40 (s, 1H), 8.35–8.18 (m, 2H), 8.03 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H).

Methyl 3-(4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-benzamido)-4-hydroxybenzoate (10g)

To an oven-dried 100 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added acid 7f (1.50 g, 5.26 mmol), 53 mL of CH2Cl2, and 10 drops of DMF. Oxalyl chloride (0.89 mL, 10.5 mmol) was added carefully, and the reaction was stirred for 2 h, where upon it was concentrated in vacuo to give a yellow semisolid. The crude acid chloride was suspended in 26 mL of CH2Cl2, and triethylamine (2.93 mL, 21.0 mmol) was added, followed by DMAP (64 mg, 0.53 mmol). The reaction was stirred for 5 min at which time aniline 9a (880 mg, 5.26 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight (18 h), quenched with 1 M HCl(aq), and diluted with CH2Cl2, causing a suspension to form in the organic layer. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (×3). The combined organic layers were diluted with hexanes and filtered to give a brown solid (1.02 g, 45% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 10.78 (br s, 1H), 10.05 (br s, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (s, 2H), 8.05 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H).

N-(5-Bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)-3′-methoxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxamide (10h)

Following general experimental procedure B, acid 7g (3.1 g, 10.5 mmol), 105 mL of CH2Cl2, oxalyl chloride (2.04 mL, 24.2 mmol), 70 mL of toluene, 35 mL of 10% NaHCO3(aq), and 9b (1.97 g, 10.5 mmol) were combined to give a brown solid which was used in the next step without further purification (3.96 g, 81% yield).

Methyl 2-(4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzo-[d]oxazole-5-carboxylate (11a)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10a (crude from previous step), 99 mL of toluene, and p-toluenesulfonic acid (3.77 g, 19.8 mmol) were combined to give a tan solid (1.1 g, 29% yield over two steps). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.56–8.49 (m, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.93–4.75 (m, 2H), 4.48–4.37 (m, 2H), 3.97 (s, 3H).

5-Bromo-2-(4′-fluoro-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-benzo[d]oxazole (11b)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10b (980 mg, 2.17 mmol), 21.7 mL of toluene, and p-toluenesulfonic acid (867 mg, 4.56 mmol) were combined to give oxazole 11b as a red solid (760 mg, 80% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7. 86 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.35 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H).

5-Bromo-2-(2′-(2-fluoroethoxy)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]oxazole (11c)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10c (1.06 g, 2.34 mmol), 23.4 mL of toluene, and p-toluenesulfonic acid (0.94 g, 4.92 mmol) were combined to give the crude product which was applied to a silica gel column, eluted with 20% EtOAc/hexanes, to provide the phenol intermediate as a red solid (820 mg, 80% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.64 (s, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.6 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H).

To an oven-dried 16 × 125 mm test tube equipped with a stir bar was added the phenol prepared above (290 mg, 0.67 mmol), cesium carbonate (437 mg, 1.34 mmol), and 2.2 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide. 2-Fluoroethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (160 mg, 0.73 mmol) was added via syringe, and the reaction vessel was placed in a preheated 70 °C oil-bath and stirred for 4 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to r.t. and diluted with EtOAc and H2O, and the layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with H2O (×5) and brine, dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated in vacuo to give a light brown solid, which was used without further purification (310 mg, 97% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.58 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.53–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (dt, J = 47.2 Hz, 4 Hz, 2H), 4.31–4.03 (m, 2H).

5-Bromo-2-(4′-(2-fluoroethoxy)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]oxazole (11d)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10d (3.4 g, 7.52 mmol), 75 mL of toluene, and p-toluenesulfonic acid (3.0 g, 15.8 mmol) were combined to give the crude product, which was applied to a silica gel column, eluted with 20% EtOAc/hexanes, to provide the phenol intermediate as a red solid (1.21 g, 37% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.77 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.4 2H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H).

To an oven-dried 16 × 125 mm test tube equipped with a stir bar was added the phenol prepared above (217 mg, 0.50 mmol), cesium carbonate (326 mg, 1.0 mmol), and 1.7 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide. 2-Fluoroethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (120 mg, 0.55 mmol) was added via a syringe, and the reaction vessel was placed in a preheated 70 °C oil-bath and stirred for 4 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to r.t. and diluted with EtOAc and H2O, and the layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with H2O (×5) and brine, dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated in vacuo to give 232 mg of a light brown solid, which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.46 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.70–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.87–4.70 (m, 2H), 4.37–4.25 (m, 2H).

2-(2,4′-Bis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-5-bromobenzo-[d]oxazole (11e)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10e (2.70 g, 5.35 mmol), 54 mL of toluene, and p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (2.14 g, 11.2 mmol) were combined to give a light red solid (2.39 g, 92% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.92–7.85 (m, 3H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.61 (m, 3H).

5-Bromo-2-(4-(6-fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-benzo[d]oxazole (11f)

To an oven-dried 25 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added amide 10f (935 mg, 2.05 mmol) and 8.2 mL of THF. Triphenylphosphine (1.19 g, 4.52 mmol) was added followed by diisopropylazodicarboxylate (0.89 mL, 4.52 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 22 h and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was diluted with diethyl ether and filtered through a Celite plug, washing with ether. The ether mixture was concentrated in vacuo and applied to a silica gel column, eluting with 15% EtOAc/hexanes to give a pink solid (500 mg, 56% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.66 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.46 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (td, J = 8.0 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.47 (m, 3H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.8 Hz, 1H).

Methyl 2-(4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-benzo[d]oxazole-5-carboxylate (11g)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10g (500 mg, 1.15 mmol), 11.5 mL of toluene, and pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (607 mg, 2.42 mmol) were combined to give a yellow solid (415 mg, 87% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.64 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.48–8.42 (m, 2H), 8.22 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (td, J = 8.0 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H).

5-Bromo-2-(3′-methoxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-benzo[d]oxazole (11h)

Following general experimental procedure C, amide 10h (3.96 g, 8.49 mmol), 85 mL of toluene, and p-toluenesulfonic acid (3.39 g, 17.8 mmol) were combined to give a red solid (3.24 g, 85% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.61 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.96–7.93 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.02–6.90 (m, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H).

(2-(4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzo[d]-oxazol-5-yl)methanol (12a)

To a 25 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added ester 11g (415 mg, 0.99 mmol) and 5 mL of THF. The reaction was cooled in a −78 °C cooling bath (CO2(s)/acetone), and DIBAl-H (2.99 mL, 2.99 mmol, 1.0 M in hexanes) was added slowly. The reaction was allowed to warm in the bath to −15 °C for 1 h, at which time TLC indicated consumption of the starting ester. The reaction was quenched with 2 mL of EtOAc and 5 mL of saturated Rochelle’s salt solution and stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc and the layers separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×2). The combined organic layers were washed with H2O, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a white solid (350 mg, 91% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.69 (s, 1H), 8.48 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.86–7.78 (m, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.86 (s, 2H).

(2-(4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzo[d]-oxazol-5-yl)methanol (12b)

To an oven-dried 50 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added ester 11a (844 mg, 2.2 mmol) and 11 mL of 2-methyltetrahydrofuran. The reaction mixture was cooled to −78 °C (CO2(s)/acetone bath), and DIBAl-H (1.0 M solution in hexanes, 6.6 mL, 6.6 mmol) was added carefully. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to −5 °C in the bath over 1 h, at which time TLC showed the consumption of the ester. The reaction was quenched with EtOAc and saturated Rochelle’s salt solution(aq), and stirred for 30 min when a precipitate had formed. The reaction mixture was filtered through a Celite plug, washing with EtOAc and water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×1). The combined organic layers were washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a white solid (743 mg, 95% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.48 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.90–4.74 (m, 2H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 4.47–4.35 (m, 2H).

5-(Chloromethyl)-2-(4-(6-fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)benzo[d]oxazole (13a)

To an oven-dried 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added 0.11 mL of DMF, followed by cyanuric chloride (194 mg, 1.05 mmol). The reaction was stirred for 30 min, at which time TLC analysis showed the consumption of the cyanuric chloride. Then, 2.5 mL of CH2Cl2 was added, followed by alcohol 12a (388 mg, 1.00 mmol). The reaction was stirred for 1 h, at which time TLC analysis showed the consumption of the alcohol. The reaction was quenched with H2O and diluted with CH2Cl2. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (×1). The combined organic layers were washed with sat. sodium carbonate solution, 1 M HCl(aq), brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give 398 mg of an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.86–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (s, 2H).

5-(Chloromethyl)-2-(4-(2-fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)benzo[d]oxazole (13b)

To an oven-dried 50 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added 0.23 mL of DMF and cyanuric chloride (218 mg, 1.18 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at which time 3 mL of CH2Cl2 and alcohol 12b (400 mg, 1.13 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h and diluted with CH2Cl2 and water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (×2). The combined organic layers were washed with sat. Na2CO3(aq), 1 M HCl (aq), and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a tan solid (250 mg, 59% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.47 (s, 1H), 8.38 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.92–4.74 (m, 2H), 4.73 (s, 2H), 4.48–4.36 (m, 2H).

Methyl 1-((2-(4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)methyl)azetidine-3-carboxy-late (14a)

To a 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added chloride 13a (260 mg, 0.64 mmol), methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride (146 mg, 0.96 mmol), 2.1 mL of acetonitrile, and potassium carbonate (265 mg, 1.92 mmol). The reaction was stirred for 3 h, at which time no progress was observed by TLC. iPr2NEt (0.33 mL, 1.92 mmol) was added and the reaction stirred for 20 h at r.t. The reaction was diluted with water and EtOAc and the layers separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×1). The combined organic layers were washed with water (×2), brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a yellow semisolid. The crude product was then purified on a silica gel column, eluting with EtOAc to give a white solid (110 mg, 35% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.63 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.43 (dd, J = 8 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (td, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (s, 2H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 3.57–3.52 (m, 2H), 3.40–3.30 (m, 3H).

Methyl 1-((2-(4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)methyl)azetidine-3-carboxylate (14b)

To a 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added chloride 13b (187 mg, 0.5 mmol), methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride (114 mg, 0.75 mmol), 1.7 mL of MeCN, and DIPEA (0.26 mL, 1.5 mmol). The reaction was placed in a preheated 60 °C oil-bath and stirred overnight (∼18 h). The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to r.t. and diluted with water and EtOAc. The layers were separated and the aqueous layer extracted with EtOAc (×2). The combined organic layers were washed with water (×3), brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a tan solid (150 mg, 66% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.85–4.67 (m, 2H), 4.40–4.28 (m, 2H), 3.75–3.65 (m, 4H), 3.55–3.45 (m, 2H), 3.36–3.25 (m, 2H).

1-((2-(4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzo-[d]oxazol-5-yl)methyl)azetidine-3-carboxylic Acid (15a)

To a 13 × 100 mm test tube equipped with a stir bar was added ester 14a (70 mg, 0.14 mmol), 1.1 mL of THF, and 0.21 mL of 2 M LiOH(aq). The reaction was stirred overnight at r.t. and quenched with 1 M HCl(aq) to give a white precipitate. The precipitate was removed by filtration and dried under reduced pressure to provide 30 mg of the product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.69 (s, 1H), 8.57 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.07–7.97 (m, 2H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (d, J = 22.4 Hz, 2H), 4.48 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 4.39–4.32 (m, 3H), 3.83–3.71 (m, 1H).

1-((2-(4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzo[d]-oxazol-5-yl)methyl)azetidine-3-carboxylic Acid (15b)

To a 10 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar and containing ester 14b (120 mg, 0.27 mmol) was added 2.1 mL of THF and 0.4 mL of 2 M LiOH(aq). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight (18 h) and quenched with 1 M HCl(aq). The reaction mixture was neutralized with sat. NaHCO3(aq), which caused the formation of a precipitate. This precipitate was filtered and washed with Et2O to give a white solid (41 mg, 35% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.50–8.43 (m, 2H), 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.86–4.71 (m, 2H), 4.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.54–4.25 (m, 6H), 3.72 (pent, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H).

5-(2-(4-(6-Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)benzo-[d]oxazol-5-yl)thiophene-2-carboxylic Acid (16)

To an oven-dried 25 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a stir bar was added palladium acetate (2.2 mg, 0.01 mmol), bromide 11f (219 mg, 0.5 mmol), 2-carboxythiophene-5-boronic acid (95 mg, 0.55 mmol), cesium fluoride (228 mg, 1.5 mmol), 1.35 mL of 1,4-dioxane, and 1.35 mL of degassed H2O. The reaction vessel was equipped with a cold finger, placed in a preheated 110 °C oil-bath, and heated overnight (∼18 h). The reaction was cooled to r.t. and poured into a 1:1 mixture of EtOAc/1 M HCl(aq). The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×3). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a brown solid (223 mg, 92% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 13.19 (br s, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (td, J = 8.0 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.8 Hz, 1H).

Methyl 1-(2-(4′-Fluoro-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (17a)

Following general experimental procedure D, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (10 mg, 0.01 mmol), XPhos (19 mg, 0.040 mmol), sodium tert-butoxide (67 mg, 0.70 mmol), oxazole 11b (218 mg, 0.5 mmol), toluene (1 mL), and methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate (81 μL, 0.60 mmol) were combined to give the crude product which was applied to a silica gel column, eluting with 5–15% ethyl acetate in hexanes to give ester 17a as a yellow solid (165 mg, 66% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.59 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.11 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.61 (dt, J = 8.8 Hz, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (td, J = 12 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (tt, J = 11.2 Hz, 4 Hz, 1H), 2.13–2.02 (m, 2H), 2.01–1.87 (m, 2H).

Methyl 1-(2-(2′-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (17b)

Following general experimental procedure D, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (6.2 mg, 0.006 mmol), XPhos (11.4 mg, 0.024 mmol), sodium tert-butoxide (40 mg, 0.42 mmol), oxazole 11c (144 mg, 0.30 mmol), toluene (0.6 mL), and methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate (48 μL, 0.36 mmol) were combined to give the crude product which was applied to a silica gel column, eluting with 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes to give ester 17b as a yellow solid (90 mg, 56% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.60 (s, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (br s, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.01 (m, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (dt, J = 47.6 Hz, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 4.29–4.04 (m, 2H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2H), 2.84 (t, J = 11.2 Hz, 2H), 2.53–2.44 (m, 1H), 2.14–2.04 (m, 2H), 2.03–1.85 (m, 2H).

Methyl 1-(2-(4′-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxy-late (17c)

Following general experimental procedure D, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (7.2 mg, 0.007 mmol), XPhos (13 mg, 0.028 mmol), sodium tert-butoxide (47 mg, 0.49 mmol), oxazole 11d (168 mg, 0.35 mmol), toluene (0.7 mL), and methylpiperidine-4-carboxylate (57 μL, 0.42 mmol) were combined to give the crude product, applied to a silica gel column, eluting with 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes to give ester 17c as a yellow solid (95 mg, 50% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.59 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.11 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.61 (dt, J = 8.8 Hz, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (td, J = 12 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (tt, J = 11.2 Hz, 4 Hz, 1H), 2.13–2.02 (m, 2H), 2.01–1.87 (m, 2H).

Methyl 1-(2-(2,4′-Bis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo-[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (17d)

Following general experimental procedure D, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (21 mg, 0.02 mmol), XPhos (38 mg, 0.08 mmol), sodium tert-butoxide (135 mg, 1.4 mmol), bromide 11e (486 mg, 1.0 mmol), and 2 mL of toluene were combined to provide the crude product. This was applied to a silica gel column, eluting with 20% EtOAc/hexanes to provide a yellow powder (265 mg, 48% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.52–7.45 (m, 4H), 7.31 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (s, 3H), 3.63 (dt, J = 12.4 Hz, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 2.84 (td, J = 11.6 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (tt, J = 10.8 Hz, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 2.13–2.04 (m, 2H), 2.02–1.87 (m, 2H).

Methyl 1-(2-(3′-Methoxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (17e)

Following general experimental procedure D, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (21 mg, 0.02 mmol), XPhos (38 mg, 0.08 mmol), sodium tert-butoxide (135 mg, 1.4 mmol), bromide 11h (447 mg, 1.0 mmol), and 2 mL of toluene were combined to provide the crude product. This was applied to a silica gel column, eluting with 20% EtOAc/hexanes to provide a yellow powder (93 mg, 18% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.60 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.38–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.00–6.87 (m, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2H), 2.84 (t, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H), 2.53–2.42 (m, 1H), 2.13–2.04 (m, 2H), 2.03–1.86 (m, 2H).

1-(2-(4′-Fluoro-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]-oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylic Acid (18a)

Following general experimental procedure E, ester 17a (150 mg, 0.30 mmol), 1.25 mL of tetrahydrofuran, 0.25 mL of H2O, and lithium hydroxide (14 mg, 0.60 mmol) were combined to give carboxylic acid 18a as an off-white pearly solid (129 mg, 89% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.93–3.74 (m, 4 H), 2.93–2.82 (m, 1H), 2.41 (dd, J = 15.2 Hz, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 2.32–2.16 (m, 2H).

1-(2-(2′-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylic Acid (18b)

Following general experimental procedure E, ester 17b (90 mg, 0.17 mmol), 0.70 mL of tetrahydrofuran, 0.13 mL of H2O, and lithium hydroxide (8.0 mg, 0.332 mmol were combined to give carboxylic acid 18b as an off-white pearly solid (82 mg, 94% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (d, J = 48 Hz, 2H), 3.31–3.05 (m, 2H), 3.68 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 3.14 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 2H), 2.59 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 2.26–2.10 (m, 2H), 2.09–1.92 (m, 2H).

1-(2-(4′-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylic Acid (18c)

Following general experimental procedure E, ester 17c (90 mg, 0.166 mmol), 0.7 mL of tetrahydrofuran, 0.13 mL of H2O, and lithium hydroxide (8.0 mg, 0.332 mmol) were combined to give carboxylic acid 18c as a light tan solid (87 mg, 99% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.50 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (s, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.77 (dt, J = 48 Hz, 4 Hz, 2H), 4.29 (dt, J = 28.8 Hz, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 3.90–3.74 (m, 4H), 2.93–2.83 (m, 1H), 2.49–2.35 (m, 2H), 2.35–2.20 (m, 2H).

1-(2-(2,4′-Bis(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo[d]-oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylic Acid (18d)

Following general experimental procedure E, ester 17d (102 mg, 0.19 mmol), 0.79 mL of THF, and 0.16 mL of H2O, and LiOH (8.9 mg, 0.37 mmol) were combined to give an off-white solid. (101 mg, 99% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.92–3.81 (m, 4H), 2.96–2.85 (m, 1H), 2.47–2.25 (m, 4H).

1-(2-(3′-Methoxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)benzo-[d]oxazol-5-yl)piperidine-4-carboxylic Acid (18e)

Following general experimental procedure E, ester 17e (92 mg, 0.18 mmol), 0.9 mL of THF, and 0.2 mL of H2O, and LiOH (8.6 mg, 0.36 mmol) were combined to give an off-white solid (72 mg, 81% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) δ = 8.62 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.37 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.95–6.89 (m, 2H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.84–3.73 (m, 2H), 3.58–3.43 (m, 2H), 2.76 (br s, 1H), 2.35–2.25 (m, 2H), 2.21–2.16 (m, 2H).

N-(Cyanomethyl)benzamide (19)

To an oven-dried 250 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added amino-acetonitrile hydrochloride (8.0 g, 86.5 mmol). Pyridine (50 mL) was carefully added dropwise via an addition funnel. Benzoyl chloride (10.5 mL, 90 mmol) was added via an addition funnel dropwise over 30 min, and the reaction was stirred overnight (20 h). Then, 70 mL of H2O was added to dissolve the pyridinium hydrochloride and precipitate the product. The new precipitate was filtered, washed with H2O, dried, and recrystallized from 95% ethanol to give a white crystalline solid (9.5 g, 69% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.22 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 0.8 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (tt, J = 7.2 Hz, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 4.31 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H).

N-((1H-Tetrazol-5-yl)methyl)benzamide (20)

To a 100 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added nitrile 19 (5.9 g, 36.8 mmol), 32 mL of DMF, sodium azide (2.51 g, 38.7 mmol), and ammonium chloride (2.17 g, 40.5 mmol). The reaction vessel was lowered into a preheated 125 °C oil-bath and stirred overnight (18 h). The reaction was cooled to r.t. and diluted with 85 mL of 2 M HCl(aq) causing the product to precipitate. The precipitate was filtered, washed with copious amounts of H2O, and air-dried to give a white fluffy solid (6.89 g, 92% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 9.27 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (tt, J = 7.2 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.76 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H).

(1H-Tetrazol-5-yl)methanamine Hydrochloride (21)

To a 250 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added amide 20 (6.89 g, 33.9 mmol) and 50.6 mL of 12 M HCl(aq). The reaction was equipped with a reflux condenser, placed in a preheated 110 °C oil-bath, and stirred at reflux overnight (18 h). The reaction was cooled to r.t., then to 0 °C causing the formation of a precipitate. The reaction mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was washed with Et2O (×2) and concentrated in vacuo to give a white solid. This solid was triturated with ethanol and dried under vacuum to give a pale yellow solid (3.59 g, 78% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ = 4.59 (s, 2H).

Methyl 4-(2-fluoroethoxy)benzoate (23)

To a 500 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (22) (5.0 g, 32.9 mmol), potassium carbonate (13.6 g, 98.6 mmol), and 219 mL of acetone. The reaction vessel was heated to reflux in a preheated 70 °C oil-bath, and stirred for 30 min. 1-Bromo-2-fluoroethane (7.34 mL, 98.6 mmol) was added via syringe, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 20 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to r.t. and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting solid was dissolved in EtOAc and H2O. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×1). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a white solid (6.25 g, 96% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.00 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 4.78 (ddd, J = 47.2 Hz, 5.6 Hz, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 4.27 (ddd, J = 27.6 Hz, 5.6 Hz, 4.4 Hz, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H).

4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)benzoic Acid (24)

To a 500 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added ester 23 (5.84 g, 29.5 mmol), followed by 98 mL of methanol, and 49 mL of H2O. NaOH (4.71 g, 118 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 16 h at r.t. The reaction was acidified with conc HCl(aq) to pH 1 and diluted with H2O. The resulting precipitate was filtered, washed with H2O and hexanes, and air-dried to give a white solid (5.41 g, 99%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.05 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.86–4.72 (m, 2H), 4.34–4.23 (m, 2H).

N′-Hydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)benzimidamide (25).33

To a 500 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added 4-(hydroxymethyl)benzonitrile (13.3 g, 100 mmol), hydroxyamine hydrochloride (11.1 g, 160 mmol), sodium bicarbonate (26.9 g, 320 mmol), and 167 mL of methanol. The reaction was equipped with a reflux condenser and lowered into a preheated 70 °C oil-bath. The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 h and then cooled to r.t. The precipitate was filtered and washed with methanol. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to give a white solid (16.5 g, 99% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d4) data match the literature values.

(4-(5-(4-Ethoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)phenyl)methanol (26a).33

Following general experimental procedure F, 4-ethoxybenzoic acid (2.49 g, 15.0 mmol), EDC·HCl (2.88 g, 15.0 mmol), HOBt (2.03 g, 15.0 mmol), 19 mL of DMF, and amidine 25 (2.49 g, 15.0 mmol) were combined to give an off-white solid (2.2 g, 50% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.18–8.11 (m, 4H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.79 (s, 2H), 4.13 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H).

(4-(5-(4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)phenyl)-methanol (26b)

Following general experimental procedure F, carboxcyclic acid 24 (2.76 g, 15.0 mmol), EDC·HCl (2.88 g, 15.0 mmol), HOBt (2.03 g, 15.0 mmol), 19 mL of DMF, and amidine 25 (2.49 g, 15.0 mmol) were combined to provide the crude product, which was used without further purification for the next step.

(4-(5-(4-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)phenyl)methanol (26c)

Following general experimental procedure F, acid 7a (3.78 g, 15.0 mmol), EDC·HCl (2.88 g, 15.0 mmol), HOBt (2.54 g, 15.0 mmol), 19 mL of DMF, and amidine 25 (2.49 g, 15.0 mmol) were combined to give an off-white solid (3.12 g, 55% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.45 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.90–4.74 (m, 4H), 4.48–4.35 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 174.4, 168.9, 159.7, 144.4, 133.4, 127.8, 127.8 (q, JC–F = 5.2 Hz), 127.3, 122.9, (q, JC–F = 274 Hz), 120.4 (q, JC–F = 32.1 Hz), 117.2, 113.5, 81.4 (d, JC–F = 173 Hz), 68.5 (d, JC–F = 21.1 Hz), 64.9. MP: 146–147 °C. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H14F4N2O3 [M + H+] 383.1013. Found [M + H+] 383.1011.

(4-(5-(4-Methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)phenyl)methanol (26d)

To a 100 mL round-bottomed flask equipped with a stir bar was added 4-methoxy-3-(trifluoromethyl)-benzoic acid (2.2 g, 10.0 mmol), HOBt (0.39 g, 2.0 mmol), TBTU (3.21 g, 10.0 mmol), 20 mL of DMF, and DIPEA (5.23 mL, 30.0 mmol). The reaction was stirred at r.t. for 30 min, and N′-hydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)benzimidamide (1.66 g, 10.0 mmol) was added. The reaction was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, heated in a 120 °C oil-bath for 3 h, and cooled to r.t. The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc and water. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (×1). The combined organic layers were washed with 1 M HCl(aq), water, sat. NaHCO3(aq), water (×3), and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a tan solid (2.6 g, 74% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.45 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (s, 2H), 4.02 (s, 3H).

4-(5-(4-Ethoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)benzaldehyde (27a).33