Abstract

Background

Clark and Wells’ (1995; Clark, 2001) cognitive model of social anxiety proposes that socially anxious individuals have negative expectations of performance prior to a social event, focus their attention predominantly on themselves and on their negative self-evaluations during an event, and use this negative self processing to infer that other people are judging them harshly.

Aims

The present study tested these propositions.

Method

The study used a community sample of 161 adolescents aged 14-18 years. The participants gave a speech in front of a pre-recorded audience acting neutrally, and participants were aware that the projected audience was pre-recorded.

Results

As expected, participants with higher levels of social anxiety had more negative performance expectations, higher self-focused attention, and more negative perceptions of the audience. Negative performance expectations and self-focused attention were found to mediate the relationship between social anxiety and audience perception.

Conclusion

The findings support Clark and Wells’ cognitive model of social anxiety which poses that socially anxious individuals have distorted perceptions of the responses of other people because their perceptions are colored by their negative thoughts and feelings.

Keywords: Social anxiety, adolescents, self-focus, cognitive bias, cognitive-behavioural intervention

1. Introduction

In Clark and Wells’ (1995; Clark, 2001) cognitive model of social anxiety, socially anxious individuals are regarded as having negative expectations for performance prior to a social event, as well as heightened self-focused attention, negative self-evaluation, and negative interpretations of other people’s responses during a social event. According to the model, focusing on oneself and one’s negative self-evaluative cognitions prevents socially anxious individuals from paying attention to actual responses from their audience, including responses which might be more positive than expected. In this way, negative cognitions are not open to correction and trait social anxiety is maintained. The aim of the present study was to test several components of Clark and Wells’ model in an adolescent sample. In particular, the study sought to determine the role of negative performance expectations and self-focused attention in the link between social anxiety and audience perception.

An important aspect of the Clark and Wells (1995; Clark, 2001) model is the proposition that negative performance expectations trigger a processing mode termed “processing of the self as social object” (Clark, 2001, p. 407). When processing oneself as a social object, socially anxious individuals focus their attention on internal anxiety-related processes, they assume that others perceive them in the same negative way as they perceive themselves, and they fail to notice the actual behaviour of others towards them. Thus, the constructs of self-focused attention and audience perception fall within the rubric of processing of the self as a social object. Clark described it this way:

When individuals with social phobia believe they are in danger of negative evaluation by others, they shift their attention to detailed monitoring and observation of themselves. They then use the internal information made accessible by self-monitoring to infer how they appear to other people and what other people are thinking about them. (Clark, 2001, pp. 407-408)

Audience perception is therefore negatively biased; that is, perceptions are more negative than is actually warranted. The biased perceptions then strengthen the socially anxious individual’s negative self-evaluative cognitions, contributing to a vicious cycle maintaining social anxiety.

As far as we are aware, empirical studies have been restricted to tests of bivariate relationships presented in the model. For example, some studies have shown that socially anxious adults (e.g., Norton & Hope, 2001; Stopa & Clark, 1993) and youth (e.g., Alfano, Beidel, & Turner, 2006; Inderbitzen-Nolan, Anderson, & Johnson, 2007) indeed think negatively about their performance. Relatively high levels of self-focused attention have also frequently been reported both in adult samples (e.g., Pineles & Mineka, 2005; Rapee & Abbott, 2007) and adolescent samples (e.g., Hodson, McManus, Clark, & Doll, 2008; Miers, Blöte, De Rooij, Bokhorst, & Westenberg, 2013) of socially anxious individuals. Furthermore, several studies have investigated socially anxious individuals’ perceptions of the behaviour of others. For example, Pozo, Carver, Wellens, and Scheier (1991) used an interview procedure with pre-recorded questions posed by interviewers showing either neutral, positive (approving), or negative (disapproving) expressions. The high socially anxious group perceived lower levels of acceptance, irrespective of the behaviour of the interviewer. Perowne and Mansell (2002) used a speech task and manipulated the behaviour of a pre-recorded “make believe” audience in such a way that some audience members showed positive behaviours while others showed neutral or negative behaviours. The speakers who were high on social anxiety perceived more negative audience evaluations of their performance relative to the low anxious speakers. The high socially anxious speakers were also higher in self-focused attention. However, the role that self-focused attention played in “misinterpreting” other people’s behaviour was not investigated.

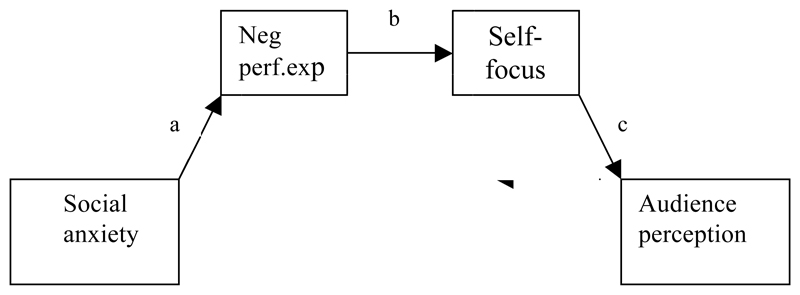

In conclusion, previous studies largely focused on bivariate relations between social anxiety and the different variables in the Clark and Wells (1995; Clark, 2001) model, while tests of the different pathways in the model are still lacking. The aim of the present study was to test some important pathways of this model in an adolescent sample. In particular, we wanted to determine what role negative self-evaluative cognitions (in the form of performance expectations) and self-focused attention play in the relation between social anxiety and audience perception (see Fig. 1). Three research questions were addressed. First, are adolescents’ perceptions of audience behaviour related to their social anxiety? We expected that higher social anxiety would be associated with more negative perceptions of audience behaviour. Second, is the proposed relation between social anxiety and negative audience perception mediated by negative expectations of performance and by self-focused attention? We expected a significant indirect effect of social anxiety on audience perception through, successively, negative expectations of performance and self-focused attention. Third, is the model presented in Figure 1 specific to social anxiety or is it more generally related to negative affect, including depression? Previous studies have failed to show, unequivocally, that negative social cognitions in adolescents are specific to social anxiety (see Miers, Blöte, Bögels, & Westenberg, 2008). We therefore checked the model’s specificity by comparing it to a model in which depression was added as covariate. We also checked that self-focused attention and not high vigilance (i.e., high self- and other-focused attention) mediates the link between social anxiety and audience perception. Other-focused attention was thus included in the analyses, along with self-focused attention

Figure 1.

Model of the relation between social anxiety and audience perception with negative performance expectations (Neg perf.exp) and self-focused attention (Self-focus) as successive mediators.

The study used a speech task procedure in order to evaluate the relation between social anxiety and perceived audience behaviour. The audience acted neutrally and could not be influenced by the speakers’ performance because it was a pre-recorded audience. The neutral behaviour of the audience created a situation in which the audience cues were ambiguous. Therefore, if speakers perceived any negative expressions in the audience this could not be ascribed to negative cues from audience members. We measured adolescents’ self-evaluative cognitions one week prior to the task in the form of expected performance. In this way, expected performance is an operationalization of Clark’s (2001) notion of “processing before a social situation” (p. 411). Audience perception and self-focused attention (components of “processing of self as a social object” during the task) were measured following the task.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were drawn from the study on Social Anxiety and Normal Development (SAND; Westenberg et al., 2009). The SAND study recruited children and adolescents from one high school and two elementary schools in the Netherlands. Participants were mainly from White middle-class families. They gave a speech on two occasions, with a period of two years in between. We used the data from the second speech and selected participants aged 14 years and older (N = 163). Their mean age was 16.00 years (SD = 1.38). Data from two participants were removed because they were outliers negatively influencing (multivariate) normality of the data. The remaining 161 participants included 82 boys and 79 girls. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University. Parents gave their informed consent and adolescents assented to participation. Participants received a monetary reward.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Audience Perception List (APL)

The APL was specifically developed for this study. It contains 4 questions: (1) Did you think the audience was interested? (2) Did you think the audience was friendly? (3) How pleasant was it to speak in front of this audience? (4) How at ease did you feel when giving your speech in front of this audience? All items had 5-point likert scales ranging from -2 to 2. For example, Question 1 was scaled as follows: -2 = uninterested, -1 = somewhat uninterested, 0 = neutral, 1 = somewhat interested, and 2 = interested. Scores were recoded from 1 to 5 to make them comparable with other measures. Additional information about the psychometrics of the APL is presented in the Results.

2.2.2. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998)

The Dutch translation (H. Koot & E. Utens, unpublished) of the SAS-A was used to measure participants’ trait social anxiety. The SAS-A consists of 18 self-descriptive items about social anxiety (e.g. “I worry about what others think of me”, “I get nervous when I meet new people”, “It’s hard to ask others to do things with me”) and four filler items, rated on a 5 point Likert-scale (from 1 = not at all to 5 = always). The mean score for the 18 self-descriptive items was used in the analyses. The internal consistency of the original version (La Greca, & Lopez, 1998, Inderbitzen-Nolan, & Walters, 2000) and the Dutch version (Blöte & Westenberg, 2007) are both good. In the present sample α was .91.

2.2.3. Expected Performance Scale (ES-before)

An adapted version of Evaluated Performance Before (ES-before; Spence, Donovan, & Brechman-Toussaint, 1999) was used to measure participants’ expected performance. The original version has five questions, for example, “Compared to other kids your age, how many mistakes do you think you will make when you are giving this speech?” For the current study, two of the questions (asking participants how they think other people will judge their speech) were split up so as to ask how they think same age peers and teachers would judge their speech. For example, one of the questions became “How good do you think a teacher watching the video will think you are at this task?” and “How good do you think the other kids your age watching the video will think you are at this task?” Items are rated on a 5-point scale. By way of example, the scale for the two items described above was: 1 = very poor, 2 = not so good, 3 = okay, 4 = rather good, and 5 = good. In the present sample α for the seven items was .76. Scores were recoded such that higher scores indicate more negative performance expectations.

2.2.4. Focus of Attention Questionnaire (FAQ; Woody, Chambles, & Glass, 1997)

We used items from the Focus of Attention Questionnaire to measure self-focused and other-focused attention. Items were adapted to the speech task by changing “the other person” to “the persons in the class”. As per the original instructions, items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (totally). To measure self-focused attention we used three items addressing self-focus on internal processes (i.e., “I was focusing on my level of anxiety”, “I was focusing on my internal bodily reactions”, and “I was focusing on past social failures”). One of the original items (“I was focusing on what I would say or do next”) was excluded because it was not relevant to the delivery of a prepared speech, and another item (“I was focusing on the impression I was making on the persons in the class”) was deleted because participants were aware that they were delivering their speech to a pre-recorded audience. In the present sample the internal consistency of the three-items measuring self-focused attention was α = .64.

To measure other-focused attention we used four items from the FAQ (“I was focusing on the appearance or dress of the persons in the class”, “I was focusing on how the persons in the class might be feeling about themselves”, “I was focusing on what I thought of the persons in the class”, and “I was focusing on what the persons in the class were doing”). The item “I was focusing on the features or conditions of the physical surroundings” was excluded because we were interested in the participants’ focus on the audience. The internal consistency of the four other-focused items was α = .62.

2.2.5. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985)

The Dutch translation (Timbremont & Braet, 2002) of the CDI was used to measure depression. The CDI contains 27 items, 26 of which were used in the present study. For ethical reasons, the item asking about suicide was removed. Each item presents three statements representing different degrees of depressed actions, feelings, and cognitions. Participants choose the one that best describes what they have experienced in the past two weeks (e.g., “I do most things okay,” “I do many things wrong,” and “I do everything wrong.”). Scale values range from 0 (least depressed) to 2 (most depressed). The average score over the 26 items was used in the analyses. The internal consistency was α = .84.

2.3. Procedure

Participants came to the university laboratory twice to take part in the Leiden Public Speaking Task (Leiden-PST; Westenberg et al., 2009). The two sessions were held one week apart. During the first session participants filled in several questionnaires, among them the SAS-A, CDI, and ES-before. The other questionnaires which were collected for the SAND study are not relevant to the present paper. The participants met assistants who would supervise the speaking task a week later. The assistants gave instructions about what topic the participants would talk about (“the kind of films you like or dislike and why, using examples to illustrate your reasoning”) and for how long (5 minutes). Participants were required to prepare for the task at home, just as they would do for a school presentation. One week later the participant gave their speech in front of a life-size pre-recorded audience. They were told beforehand that the audience was pre-recorded but that at a later time their performance would be evaluated by same-age peers and teachers. Participants were standing in front of a 1.5 by 2 m screen on which the audience was projected. No soundtrack was included. Two audiences of different ages were used to best match the age of the participants to the filmed audience. All participants had a different audience compared to the one they had when they presented their first speech two years earlier. The audience showed four boys, four girls, and a female teacher walking into an empty classroom and then sitting down. The persons in the audience had been coached by a professional drama director to act neutrally in a natural way. Several takes were made and the best one as rated by six experts was chosen. These experts independently ranked the takes taking both the naturalness and neutrality of the audience members into account. Final decisions were made by discussion.

By behaving neutrally the audience members only presented ambiguous cues to the speakers. Therefore, if speakers perceived negative expressions in the audience this could not be ascribed to cues from audience members behaving negatively. After all audience members were seated the participant was asked to start the speech. If participants stopped before 5 minutes had expired they were prompted to continue their speech. After 5 minutes participants were asked to stop and the audience projection was turned off. Participants then used visual analogue scales to indicate how nervous they had been during their speech and how nervous they were after their speech, and completed two questionnaires for the purpose of other SAND studies (i.e., Evaluated Performance after, Spence et al. [1999] and Cartwright-Hatton and colleagues’ [2005] Performance Questionnaire) . Consecutively, the APL and the FAQ were completed.

2.4. Data analysis

First, we checked whether the four items of the APL were measuring independent aspects of audience perception or the same underlying construct. Second, descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the study variables were computed. The correlation between social anxiety and audience perception would answer the first research question as to whether social anxiety and audience perception were negatively related. Third, to address the question about whether expected performance and self-focused attention mediate the relation between social anxiety and audience perception, we used the MED3C macro (Hayes, 2010). The macro computes Ordinary Least Square regressions which allowed us to estimate direct and indirect effects of social anxiety on audience perception, and to produce percentile-based bootstrap confidence intervals and standard errors of the indirect effects (see Hayes, Preacher, & Myers, 2011). We used 1000 bootstrap samples. In a further analysis of the model we added depression as covariate in order to determine whether it is social anxiety per se or negative affect in general that predicts audience perception.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses related to the APL are presented in Table 1. The inter-correlations among the four APL items were between r = .28 and r = .58, with corrected item-total correlations between r = .48 and r = .62. Cronbach’s α of the APL was .74. All four items were significantly (negatively) related to the SAS-A. The four items of the APL were thus regarded as measuring one construct and the average score across the four items was used in the analyses.

Table 1. Reliability of the Audience Perception List Items.

| M | SD | Corrected Item-total correlation | Correlation with SAS-A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Audience is interested | 2.77 | 1.01 | .50 | -.25** |

| 2. Audience is friendly | 3.21 | 0.74 | .48 | -.18* |

| 3. Audience is pleasant to speak to | 3.13 | 1.07 | .62 | -.27** |

| 4. Feel at ease with the audience | 3.56 | 1.05 | .54 | -.32** |

p < .05, two-tailed;

p < .01, two-tailed

SAS-A: Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for the study variables. Variables are represented as mean item score per subscale or mean item score per instrument. The mean score for social anxiety was 2.11, which is close to that reported by La Greca and Lopez (1998; mean item score of 2.17 in a community sample). There was a wide range of social anxiety scores across participants. Twenty-four participants (15%) had a mean score > 2.78, meeting the criterion for a clinically high level of social anxiety (La Greca, 1998; criterion is > 2.77). With respect to focus of attention, participants were generally more other-focused than self-focused; this difference in focus of attention was significant, t(159) = 7.31. p < .01.

Table 2. Ms, SDs and Intercorrelations of the Study’s Variables (N = 160).

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Audience perception | 3.17 | 0.73 | - | |||||

| 2. Negative performance expectations | 2.75 | 0.48 | -.27** | - | ||||

| 3. Self-focused attention | 1.62 | 0.68 | -.32** | .35** | - | |||

| 4. Other-focused attention | 2.20 | 0.79 | .00 | .06 | .10 | - | ||

| 5. Social anxiety | 2.11 | 0.58 | -.34** | .32** | .43** | .12 | - | |

| 6. Depression | 0.35 | 0.22 | -.15 | .31** | .35** | .27** | .46** | - |

p < .01, two-tailed

3.2. Correlational analyses

As expected, participants with higher social anxiety perceived the audience as less positive (see Table 2). More specifically, they thought the audience was less interested, less friendly, less pleasant to speak to, and they felt less at ease with them (see Table 1).

With respect to the hypothesized mediating roles of negative performance expectations and self-focused attention, the correlations showed that both variables were significantly related to social anxiety and audience perception. As expected, higher social anxiety was associated with more negative performance expectations and higher self-focused attention, and negative performance expectations and self-focused attention were associated with less positive audience perception. Other-focused attention was not related to social anxiety, audience perception, or negative performance expectations. We therefore did not include other-focused attention in the subsequent analyses. Depression was significantly related to all variables except audience perception.

3.3. Mediation

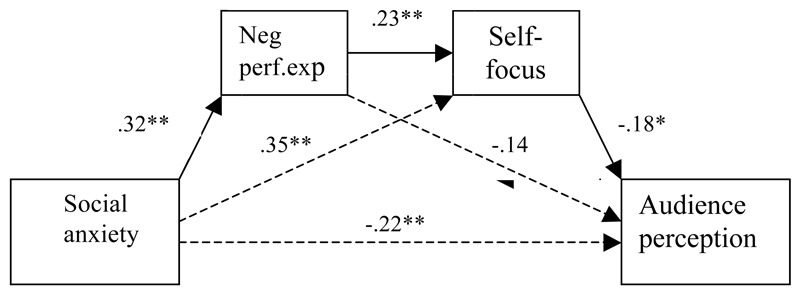

Figure 2 presents the standardized path coefficients in the mediation model. Table 3 presents the indirect effects with confidence intervals. The expected path from social anxiety via negative performance expectations and self-focused attention to audience perception was significant. An additional path from social anxiety through self-focused attention to audience perception was also significant, whereas the path through negative performance expectations was not significant. Given that the direct path from social anxiety to audience perception was significant (see Fig. 2) the mediation effects were only partial.

Figure 2.

Standardized path estimates of the mediation model with negative performance expectations (Neg perf.exp) and self-focused attention (Self-focus) as mediators.

Notes. Numbers are standardized path estimates; * p<.05, ** p<.01. Bolded lines indicate pathways in the proposed model and dotted lines alternative pathways.

Table 3. Indirect Effects in the Social-Anxiety Audience-Perception Model with Negative Performance Expectations and Self-focused Attention as Mediators(M1 and M2); First without and then with Depression as Covariate.

| Effect | LL95%CI | UL95%CI | BootSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression not included | ||||

| Total | -.12 | -.19 | -.05 | .04 |

| M1 (Negative performance expectations) | -.04 | -.10 | .004 | .03 |

| M2 (Self-focused attention) | -.06 | -.12 | -.01 | .03 |

| M1 & M2 | -.01 | -.03 | -.001 | .01 |

| Depression as covariate included | ||||

| Total | -.10 | -.17 | -.04 | .03 |

| M1 (Negative performance expectations) | -.03 | -.09 | .001 | .02 |

| M2 (Self-focused attention) | -.05 | -.12 | -.01 | .03 |

| M1 & M2 | -.01 | -.02 | -.001 | .01 |

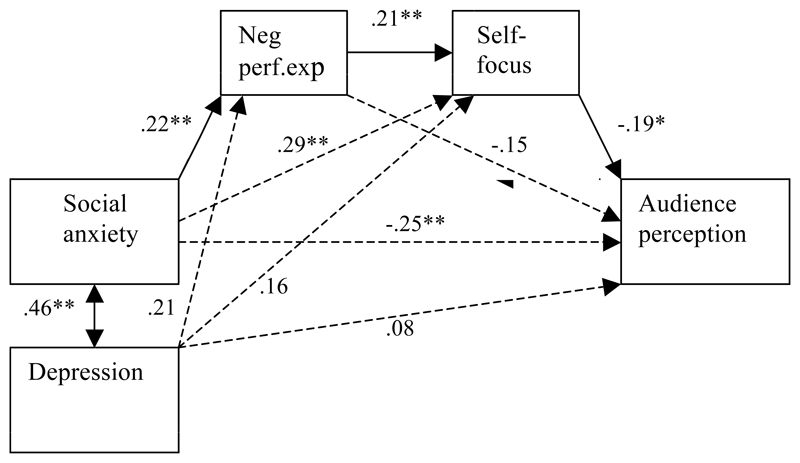

In a follow-up analysis with depression added as covariate, the path coefficients did not substantially change (see Fig. 3) and the results of the tests of indirect effects replicated those of the original model (see Table 3).

Figure 3.

Standardized path estimates of the mediation model with negative performance expectations (Neg perf.exp) and self-focused attention (Self-focus) as mediators and depression as covariate. Notes. Numbers are standardized path estimates; * p<.05, ** p<.01. Bolded lines indicate pathways in the proposed model and dotted lines alternative pathways.

4. Discussion

Using a sample of adolescents, this study tested an important part of Clark and Wells’ (1995; Clark, 2001) cognitive model of social anxiety. As expected, we found that audience perception was related to adolescents’ social anxiety. The higher their social anxiety, the more negative their perceptions of the audience were. The link between social anxiety and audience perception was partly mediated by, successively, negative expectations of performance and self-focused attention. Furthermore, these findings were specific to social anxiety and cannot be ascribed to a pattern of negative emotions related to depression. The findings offer direct support for Clark and Wells’ (1995; Clark, 2001) cognitive model of social anxiety. In the vocabulary of the model, negative “processing before a social situation” triggers “processing of the self as a social object” while in the situation, and as a result the socially anxious individual is “.. less likely to notice any signs of being accepted by other people” and will partly base their judgments about others’ responses on self-judgments (Clark, 2001, p. 411).

The results regarding the link between social anxiety and negative audience perception are in line with those of previous adult studies using a procedure involving “pre-recorded others”. These studies found that socially anxious individuals think that prerecorded others are less accepting (Pozo et al., 1991) and less positive about their performance (Perowne & Mansell, 2002). Unlike the procedure in these two studies, participants in the present study were told beforehand that the audience was pre-recorded. This approach has the advantage that participants have full knowledge of the situation and their attention is not drawn away from the task because they are wondering whether the audience is really watching them. It is important to note that although our participants were fully aware that the audience was pre-recorded, and thus audience behaviour could not have been influenced by participant’s speech performance, higher socially anxious participants nevertheless interpreted this audience behaviour as less positive.

Furthermore, in the present study - and in contrast with the studies of Perowne and Mansell (2002) and Pozo et al. (1991) - audience behaviour was neutral. The present study extends our knowledge about the perceptions of socially anxious individuals by showing that socially anxious individuals interpret neutral behaviour in a negative way. This suggests that socially anxious individuals do not need negative cues in an audience to construe negative perceptions; rather, these perceptions are driven by negative internal processes.

The present study is the first to provide empirical support for the mediating role of negative self-evaluative cognitions (measured as negative performance expectations) and self-focused attention in the link between social anxiety and audience perception. The stronger of these two was self-focused attention as it directly predicted audience perception whereas negative performance expectations only predicted audience perception via its link with self-focused attention. On the basis of high levels of self-focused attention in a socially anxious group, Perowne and Mansell (2002) argued that the negatively biased perceptions of audience behaviour as held by high socially anxious individuals might be the result of a focus on internal processes. The present study supports this proposition.

Furthermore, the present study corroborated findings from previous studies concerning the link between youths’ social anxiety and negative self-evaluations (e.g., Alfano et al., 2006; Inderbitzen-Nolan et al., 2007) or self-focused attention (Hodson et al., 2008; Miers et al., in press). The results are also in line with those reported by Pineless and Mineka (2005) who found that high socially anxious individuals show an attentional bias towards internal but not external cues of potential threat. In the present study, other-focused attention, unlike self-focused attention, was neither related to social anxiety nor audience perception.

At the same time, other-focused attention was relatively high in our sample, irrespective of social anxiety level. This suggests that individuals with higher levels of social anxiety do not show a completely “closed circuit” reaction in social situations (Schultz & Heimberg, 2008, p. 1214). They focus their attention not only on their internal processes but also on the audience. This finding is consistent with the cognitive models of Clark and Wells (1995) and Rapee and Heimberg (1997; see also Heimberg, Brozovich, & Rapee, 2010; Schultz & Heimberg, 2008). Both models emphasize negatively biased external attention as well as problematic self-processing, although the former is more prominent in Rapee and Heimberg’s writings. Given that the link between social anxiety and audience perception was only partially mediated by negative self-evaluation and self-focused attention, it is possible that a specific focus on negative cues in the audience is a third mediator. Unfortunately the method of the present study did not permit investigation of this hypothesis. That is, there were no explicit negative cues in the audience and the measure used for external focus did not specifically address negative external cues. It is thus not possible to draw conclusions about what the speakers were paying attention to.

Clark and Wells’ (1995; Clark, 2011) model describes how social anxiety is maintained in adults. We used a sample of adolescents aged 14 to 18 years and found support for (parts of) the model in this age group. The question arises as to whether our findings can be generalized to adults. Considering that the prevalence rate of social anxiety increases during adolescence and levels off in emerging adulthood (Miers et al., in press) it is probable that the pathway we found between social anxiety and audience perception should hold for adults too. At the same time, it may be difficult to generalize the findings to younger adolescents because in early adolescence social anxiety is often still emerging. In future studies attention should be given to the phase of development in which these associations arise.

To answer the question of why socially anxious youth become negative in their self-evaluations in the first place, the role of negative feedback from others like peers should be considered (e.g., Blöte, Bokhorst, Miers, & Westenberg, 2011; Verduin & Kendall, 2008). It is likely that, from an early age, some socially anxious individuals received negative responses in social situations because of a lack of social skills (Spence et al., 1999) or because of withdrawn behaviour that is not accepted in the peer group (Ollendick & Hirshfeld-Becker, 2002; Stormshack et al., 1999). Based on these experiences, young people might develop negative self-evaluations as well as negative expectations regarding responses from other people. Longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the intertwining of these internal and external factors in the development of social anxiety.

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, conceptually there may be some overlap between certain APL items and the SAS-A. For example, Item 4 in the APL asks how “at ease” the adolescent felt when giving their speech in front of the audience. By the same token, other items in the APL would appear to be more exclusively associated with audience perception (e.g., “did you think the audience was interested?”). Statistically, we observed that the items of the APL were internally consistent and only moderately related with the SAS-A. Nevertheless, future studies might benefit from adding more items that exclusively address audience perception. Second, the scale of self-focused attention comprised just 3 items and it had a rather modest internal consistency. Third, the other-focused attention scale had rather low internal consistency. In future studies investigating other-focused attention, a more sophisticated measure that assesses what participants focus on in the external environment would be preferable. Eye-tracking technology could be used for this purpose. Fourth, we used a community sample in which there was a wide range of social anxiety, including some participants who were not at all anxious and some who reported clinical levels of social anxiety. It remains unclear as to whether Clark and Wells’ (1995) model holds among young people with social anxiety disorder.

Replication is required before definitive clinical implications can be offered. In the meantime, the findings seem to support the commonly held notion that cognitive maintenance factors (i.e., negative expectations of performance and negative perceptions of others’ reactions) should be addressed in treatment for social anxiety. Consistent with this, a recent review (Lampe, 2009) concluded that cognitive therapy appears to enhance exposure-based therapies for social anxiety disorder. A more unique contribution of the present study stems from the relationship found between social anxiety and self-focused attention. This points to the importance of modifying internal self-focused processes occurring during social interactions. Shifting to an external focus of attention fits well with the more performance based forms of cognitive therapy (e.g., Clark et al., 2006) that rely more on the use of behavioural experiments to change negative cognitions. In such behavioural experiments, clients are encouraged to specify the worst that they think could happen in a social situation if they were to drop their safety behaviours and then to test out whether the prediction is correct. Focusing externally is essential for such experiments as it ensures that actual outcomes, rather than imagined outcomes, can be observed. It is worth keeping in mind, however, that increased external focus could increase the risk for negative perceptions of the audience. In such cases the newer acceptance-based treatments for social anxiety may be useful (e.g., Dalrymple & Herbert, 2007; Kocovski, Fleming, & Rector, 2009). Interventions such as cognitive defusion (i.e., diverting attention away from the content or meaning of thoughts) may help to break the debilitating interplay between negative cognitions and feelings of anxiety.

References

- Alfano CA, Beidel DB, Turner SM. Cognitive correlates of social phobia among children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:189–201. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöte AW, Bokhorst CL, Miers AC, Westenberg PM. Why are socially anxious adolescents rejected by peers? The role of subject-group similarity characteristics. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;22:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Blöte AW, Westenberg PM. Socially anxious adolescents’ perception of treatment by classmates. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, Tschernitz N, Gomersall H. Social anxiety in children: Social skills deficit or cognitive distortion? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM. A cognitive perspective on social phobia. In: Crozier WR, Alden LE, editors. International handbook of social anxiety. Chichester: Wiley; 2001. pp. 405–430. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell MJV, Waddington L, Grey N, Wild J. Cognitive therapy and exposure plus applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:568–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple KL, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:543–568. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. MED3C. 2010 Macro retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html.

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ, Myers TA. Mediation and the estimation of indirect effects in political communication research. In: Bucy EP, Holbert RL, editors. Sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures and analytical techniques. New York: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Brozovich FA, Rapee RM. A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, editors. Social anxiety, clinical, developmental, and social perspectives. New York: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson KJ, McManus FV, Clark DM, Doll H. Can Clark and Wells’ (1995) cognitive model of social phobia be applied to young people? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:449–461. [Google Scholar]

- Inderbitzen-Nolan HM, Anderson ER, Johnson HS. Subjective versus objective behavioral ratings following two analogue tasks: A comparison of socially phobic and non-anxious adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inderbitzen-Nolan HM, Walters KS. Social Anxiety Scale for adolescents: Normative data and further evidence of construct validity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2000;29:360–371. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Rector NA. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy for social anxiety disorder: An open trial. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16:276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescence: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe LA. Social anxiety disorder: Recent developments in psychological approaches to conceptualization and treatment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;43:887–898. [Google Scholar]

- Miers AC, Blöte AW, Bögels SM, Westenberg PM. Interpretation bias and social anxiety in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:1462–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miers AC, Blöte AW, De Rooij M, Bokhorst CL, Westenberg PM. Trajectories of Social Anxiety during Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood and Relations with Cognition, Social Competence, and Temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:97–110. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9651-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hope DA. Kernels of truth or distorted perceptions: Self and observer ratings of social anxiety and performance. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:765–786. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Hirshfeld-Becker DR. The developmental psychopathology of social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:44–58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perowne S, Mansell W. Social anxiety, self-focused attention, and the discrimination of negative, neutral and positive audience members by their nonverbal behaviors. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;30:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Mineka S. Attentional biases to internal and external sources of potential threat in social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:314–318. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo C, Carver CS, Wellens AR, Scheier MF. Social anxiety and social perception: Construing other’s reactions to the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17:355–362. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Abbott MJ. Modelling relationships between cognitive variables during and following public speaking in participants with social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2977–2989. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz LT, Heimberg RG. Attentional focus in social anxiety disorder : Potential for interactive processes. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1206–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH, Donovan C, Brechman-Toussaint M. Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:211–221. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopa L, Clark DM. Cognitive processes in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:255–267. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90024-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, Bruschi C, Dodge KA, Coie JD, et al. The relation between behavior problems and peer preference in different classroom contexts. Child Development. 1999;70:169–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B, Braet C. Children’s Depression Inventory: Nederlandstalige versie [Children’s Depression Inventory: Dutch version] Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Verduin TL, Kendall PC. Peer perceptions and liking of children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:459–469. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg PM, Bokhorst CL, Miers AC, Sumter SR, Kallen VL, van Pelt J, Blöte AW. A prepared speech in front of a pre-recorded audience: Subjective, physiological, and neuroendocrine responses to the Leiden Public Speaking Task. Biological Psychology. 2009;82:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody SR, Chambless DL, Glass CR. Self-focused attention in the treatment of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:117–129. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]