Abstract

Corneal endothelial cells (CECs) play a crucial role in maintaining corneal clarity through active pumping. A reduced CEC count may lead to corneal edema and diminished visual acuity. However, human CECs are prone to compromised proliferative potential. Furthermore, stimulation of cell growth is often complicated by gradual endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EnMT). Therefore, understanding the mechanism of EnMT is necessary for facilitating the regeneration of CECs with competent function. In this study, we prepared a primary culture of bovine CECs by peeling the CECs with Descemet's membrane from the corneal button and demonstrated that bovine CECs exhibited the EnMT process, including phenotypic change, nuclear translocation of β-catenin, and EMT regulators snail and slug, in the in vitro culture. Furthermore, we used a rat corneal endothelium cryoinjury model to demonstrate the EnMT process in vivo. Collectively, the in vitro primary culture of bovine CECs and in vivo rat corneal endothelium cryoinjury models offers useful platforms for investigating the mechanism of EnMT.

Keywords: Developmental Biology, Issue 114, Corneal endothelium, mesenchymal transition, matrix metalloproteinase, β-catenin, N-cadherin, intracameral injection

Introduction

Corneal endothelial cells (CECs) play a vital role in maintaining corneal clarity and thus visual acuity by regulating the hydration status of the corneal stroma through active pumping1. Because of the limited proliferative potential of human CECs, the cell number decreases with age, and the repair of corneal endothelial wounds following injury is usually achieved through cell enlargement and migration, rather than cell mitosis2. When the CEC count decreases below a threshold of approximately 500 cells/mm2, the dehydration status of the corneal stroma cannot be maintained, leading to bullous keratopathy and vision impairment3,4.

The limited proliferative potential of human CECs has been attributed to several factors, including reduced expression of the epidermal growth factor and its receptor in aging cells5, antiproliferative TGFβ2 in the aqueous humor6, and contact inhibition2,7. Although some growth factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), can increase proliferation in a cultured human corneal endothelium, the culture efficiency remains limited8,9. Furthermore, CECs may undergo a phenotypic change during ex vivo expansion, resembling epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)10-13. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EnMT) is characterized by cell junction destabilization, apical-basal polarity loss, cytoskeletal rearrangement, alpha smooth muscle actin expression, and type I collagen secretion14. All of these characteristics may abrogate the normal function of CECs, hampering the use of ex vivo cultured CECs in tissue engineering. Moreover, EnMT has been associated with the pathogenesis of several corneal endothelial diseases, including Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy and retrocorneal membrane formation15,16. Therefore, understanding the mechanism of EnMT may aid in manipulating the EnMT process and facilitate the regeneration of CECs to enable competent function.

In this study, we described a method for isolating bovine CECs from the corneal button. In the primary culture in vitro, the EnMT process, including a phenotypic change, the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, and EMT regulators snail and slug, was observed. We further described a method for demonstrating EnMT in vivo by using a rat corneal endothelium cryoinjury model. Using these 2 models, we demonstrated that marimastat, a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor, can suppress the EnMT process. The described protocols facilitate the detailed analysis of the EnMT mechanism and the development of strategies for manipulating the EnMT process for further clinical application.

Protocol

All the procedures followed in this study accorded with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital.

1. Isolation, Primary Culture Preparation, and Immunostaining of Bovine CECs

Acquire fresh bovine eyes from a local abattoir.

Disinfect the eyes in a 10% w/v povidone-iodine solution for 3 min. Wash them with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution.

Harvest the corneal button with a scalpel and scissors under sterile conditions. Peel the Descemet's membrane with forceps under a dissecting microscope (note that in this study, the bovine eyes were enucleated by a local abattoir; therefore, the first study procedure was the disinfection of the preenucleated eyes in the laboratory).

Incubate the Descemet's membrane in 1 ml of trypsin at 37 °C for 30 min. Collect the bovine CECs by centrifugation at 112 x g for 5 min. Resuspend the cells in 1 ml of supplemented hormonal epithelial medium (SHEM) containing equal volumes of HEPES-buffered Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium and Ham's F12 medium, supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 2 ng/ml of human epidermal growth factor, 5 mg/ml of insulin, 5 mg/ml of transferrin, 5 ng/ml of selenium, 1 nmol/l of cholera toxin, 50 mg/ml of gentamicin, and 1.25 mg/ml of amphotericin B.

Seed the cells (approximately 1 x 105 cells per eye) into a 6 cm dish. Culture them in the SHEM. Incubate the dish at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Change the culture medium every 3 days.

- When the cells reach confluence, wash them in PBS and incubate them in 1 ml of trypsin at 37 °C for 5 min. Collect them by centrifugation at 112 x g for 5 min. Re-suspend the cell pellet in 1 ml of the SHEM.

- Count the cells in a hemocytometer. Seed the cells on cover slides at a density of 1 x 104 per well in a 24-well plate, and culture the cells in the SHEM. For investigating the EnMT-suppressing effect of marimastat, incubate the cells in SHEM with 10 µM of marimastat added into the culture medium, and change the culture medium every 3 days.

Fix the cells at an indicated time point with 250 µl of 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4, for 30 min at room temperature. Permeabilize with 250 µl of 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Block with 10% bovine serum albumin for 30 min.

Incubate the cells with primary antibodies against active beta-catenin (ABC), snail, and slug overnight at 4 °C. The dilution of the primary antibodies used is 1:200. The antibodies are diluted in antibody diluent composed of 10 mM PBS, 1% w/v bovine serum albumin, and 0.09% w/v sodium azide.

Wash the cells twice with PBS for 15 min, and incubate them with the Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (1:100 in antibody diluent) at room temperature for 1 hr.

Counterstain the cell nucleus by covering the cells with 2 µg/ml of 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, wash the cells twice with PBS for 15 min, and mount them with anti-fading mounting solution.

Obtain immunofluorescent images at the excitation wavelengths of 405 and 488 nm by using a laser scanning confocal microscope with 20X objective magnification.

2. Rat Corneal Endothelium Cryoinjury Model and Intracameral Injection

Anesthetize 12 week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats with intramuscular injections of 2% xylazine (5.6 mg/kg) and tiletamine plus zolazepam (18 mg/kg). Gently pinch the skin of the animals to confirm proper anesthesia in the absence of skin twitching.

Instill one drop of 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride to the right eye of each rat to minimize eye pain and the blink reflex. Instill tetracycline ointment to the left eye to prevent corneal dryness.

Cool a stainless steel probe (diameter = 3 mm) in liquid nitrogen. Apply the stainless steel probe to the central cornea of the right eye for 30 sec. Frequently instill PBS to the right eye during the procedure to prevent corneal dryness.

- Instill 0.1% atropine and 0.3% gentamicin sulfate immediately after cryoinjury and once daily to relieve ocular pain resulting from ciliary spasm and to prevent infection.

- After the procedure, keep the rats warm using a heat lamp, and observe their recovery every 15 min after anesthesia until they regain motor control. Additionally, apply tetracycline ointment to the right eye to prevent corneal dryness during the recovery period.

Repeat the corneal cryoinjury for 3 consecutive days.

For delivering marimastat or bFGF into the anterior chamber of the rat eyes, anesthetize the rats as described previously. Instill one drop of 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride into the right eye to minimize eye pain and the blink reflex.

Irrigate the ocular surface with sterile PBS. Perform anterior chamber paracentesis under an operating microscope by inserting a 30 G needle attached to a 1 ml syringe at the paralimbal clear cornea in a plane above and parallel to the iris.

Turn the needle bevel up, and slightly depress the corneal wound to drain some aqueous humor and reduce the intraocular pressure. Inject 0.02 ml of the drug intracamerally. Gently compress the needle tract with a cotton tip during the needle withdrawal.

Photograph the external eye at an indicated time point under the operating microscope.

3. Harvesting the Rat Corneal Button and Immunostaining

To euthanize the rats, place them in a euthanasia chamber and infuse 100% CO2 at a fill rate of 10-30% of the chamber volume per minute. Maintain CO2 infusion for an additional minute after lack of respiration and faded eye color.

Penetrate the rat eye at the limbus with a sharp blade. Cut the corneas with corneal scissors along the limbus. Flatten the corneas on a slide. Make additional radial incisions if the corneas curl up.

Fix the corneas with 250 µl of 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4, for 30 min at room temperature. Permeabilize with 250 µl of 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and block with 10% bovine serum albumin for 30 min.

Incubate the corneas with primary antibodies against ABC overnight at 4 °C with a dilution of 1:200 in antibody diluent. Wash the corneas twice with PBS for 15 min, and incubate them with the secondary antibody (1:100 in antibody diluent) at room temperature for 1 hr. Counterstain the cell nucleus by covering the cells with 2 µg/ml of 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and wash the cells twice with PBS for 15 min.

Mount the corneas in anti-fading mounting solution. Obtain the immunofluorescent images at excitation wavelengths of 405 and 561 nm with a laser scanning confocal microscope at 20X objective magnification.

Representative Results

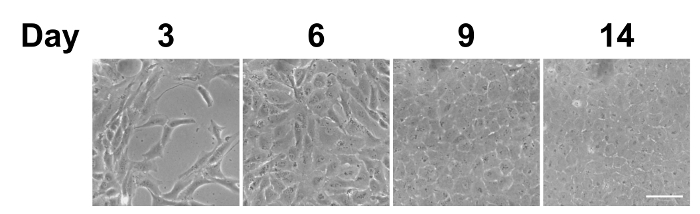

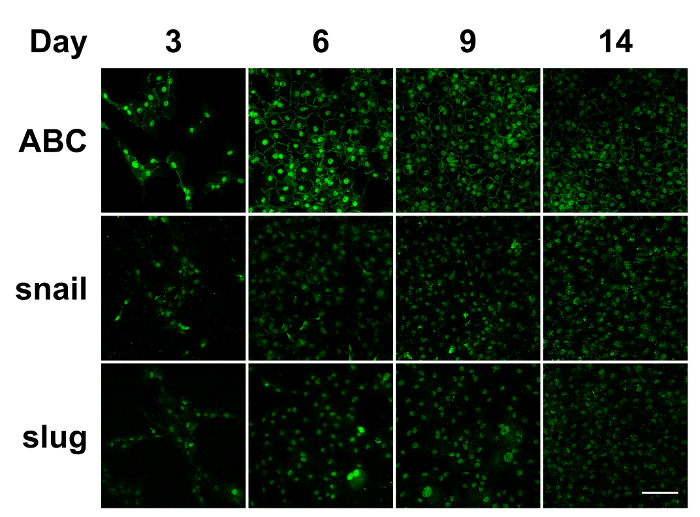

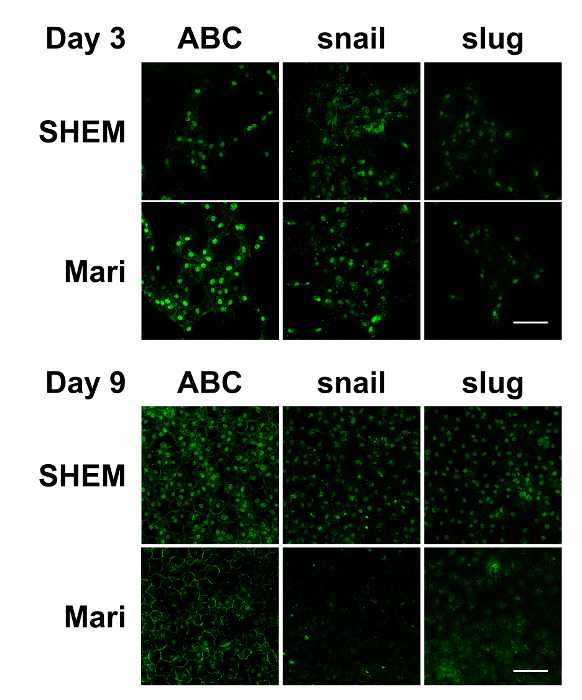

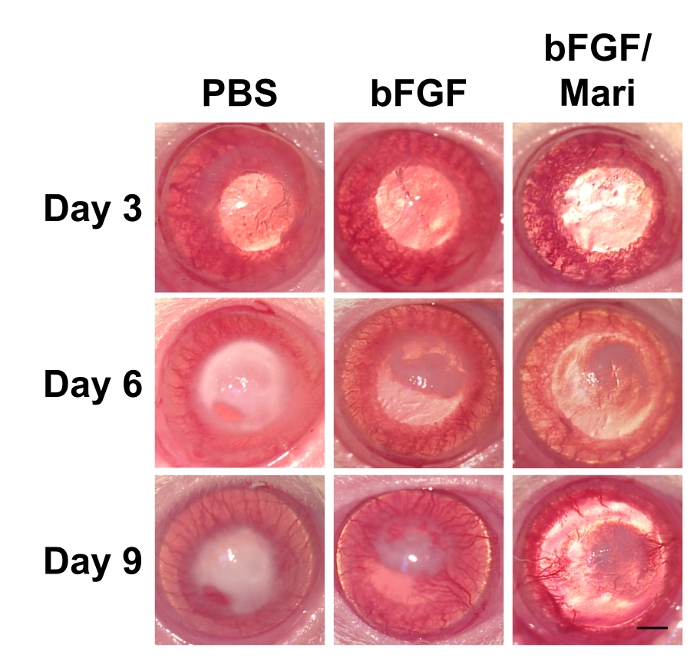

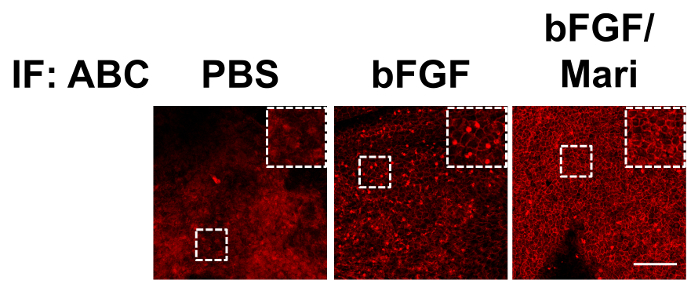

After the isolation of bovine CECs, the cells were cultured in vitro. Figure 1 presents the phase contrast images of the bovine CECs. The hexagonal shape of the cells at confluence indicated that the cells were not contaminated by corneal stromal fibroblast during cell isolation. Figure 2 depicts the immunostaining that was performed using antibodies against ABC, snail, and slug at an indicated time point. Apart from phenotypic changes in the in vitro culture, a corresponding nuclear translocation of ABC and EMT regulators was observed. Figure 3 illustrates the effect of marimastat, a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor, on the EnMT process of the in vitro cultured bovine CECs. Figure 4 comprises the external eye photographs of rats after cryoinjury followed by intracameral injection. Figure 5 shows the immunostaining of the rat corneal button that was performed using antibodies against ABC after cryoinjury followed by intracameral injection. The nuclear translocation of ABC was observed in the PBS group and was significantly increased in the bFGF group, indicating activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling and EnMT process. After intracameral injection of bFGF followed by marimastat injection, the nuclear staining of ABC was diminished, suggesting the EnMT-inhibiting effect of marimastat.

Figure 1: Phase contrast images of in vitro cultured bovine CECs. After being seeded on the culture plate, the bovine CECs initially appeared fibroblast-like on days 3 and 6. They became more hexagonal upon reaching complete confluence on day 9. Scale bar = 50 µm. Representative images of 3 replicates. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1: Phase contrast images of in vitro cultured bovine CECs. After being seeded on the culture plate, the bovine CECs initially appeared fibroblast-like on days 3 and 6. They became more hexagonal upon reaching complete confluence on day 9. Scale bar = 50 µm. Representative images of 3 replicates. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Immunostaining of in vitro cultured bovine CECs. During the in vitro culture of the bovine CECs, the nuclear translocation of ABC, snail, and slug was detected through day 14. ABC: active β-catenin. Scale bar = 100 µm. Representative images of 3 replicates. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Immunostaining of in vitro cultured bovine CECs. During the in vitro culture of the bovine CECs, the nuclear translocation of ABC, snail, and slug was detected through day 14. ABC: active β-catenin. Scale bar = 100 µm. Representative images of 3 replicates. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Immunostaining of in vitro cultured bovine CECs with or without marimastat at different cell confluence levels. Immunostaining demonstrated that ABC, snail, and slug were evident in the nucleus of the bovine CECs with or without 10 µM of marimastat on day 3. However, marimastat significantly reduced the nuclear staining of ABC, snail, and slug on day 9 when the bovine CECs became fully confluent. Scale bar = 100 µm. Representative images of 3 replicates. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Immunostaining of in vitro cultured bovine CECs with or without marimastat at different cell confluence levels. Immunostaining demonstrated that ABC, snail, and slug were evident in the nucleus of the bovine CECs with or without 10 µM of marimastat on day 3. However, marimastat significantly reduced the nuclear staining of ABC, snail, and slug on day 9 when the bovine CECs became fully confluent. Scale bar = 100 µm. Representative images of 3 replicates. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: External eye photographs of rats at indicated time points after cryoinjury. Following cryoinjury for 3 consecutive days, rats were subjected to intracameral injection of 0.02 ml of PBS or 50 ng/ml bFGF on day 3. On day 6, 0.02 ml of 10 µM marimastat was injected intracamerally in the bFGF/Mari group, whereas PBS was injected in the other 2 groups (n = 9 in each group). External eye photographs revealed reduced corneal edema after bFGF injection, whereas marimastat further reduced corneal edema compared with bFGF alone. n = 9 in each group. Scale bar = 1 mm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: External eye photographs of rats at indicated time points after cryoinjury. Following cryoinjury for 3 consecutive days, rats were subjected to intracameral injection of 0.02 ml of PBS or 50 ng/ml bFGF on day 3. On day 6, 0.02 ml of 10 µM marimastat was injected intracamerally in the bFGF/Mari group, whereas PBS was injected in the other 2 groups (n = 9 in each group). External eye photographs revealed reduced corneal edema after bFGF injection, whereas marimastat further reduced corneal edema compared with bFGF alone. n = 9 in each group. Scale bar = 1 mm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Immunostaining of rat corneal buttons. Immunostaining of the rat corneal buttons that were harvested on day 9 revealed little nuclear staining of ABC in the PBS group. In the bFGF group, there was extensive nuclear staining of ABC, which was significantly reduced in the bFGF/Mari group. Scale bar = 100 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Immunostaining of rat corneal buttons. Immunostaining of the rat corneal buttons that were harvested on day 9 revealed little nuclear staining of ABC in the PBS group. In the bFGF group, there was extensive nuclear staining of ABC, which was significantly reduced in the bFGF/Mari group. Scale bar = 100 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

CECs are known for their propensity to undergo EnMT during cell proliferation. To develop strategies for suppressing the EnMT process for therapeutic purposes, a thorough understanding of the EnMT mechanism is necessary. We described 2 models to investigate EnMT, namely the bovine CEC in vitro culture model and rat corneal endothelium cryoinjury model. Our results demonstrated the EnMT process in both models. Furthermore, the EnMT-suppressing effect of marimastat was reproduced in both models, suggesting that these 2 models share the same mechanism.

The bovine CEC in vitro culture model offers ease of manipulation. In addition, compared with the human or primate CEC in vitro culture models employed in previous studies17,18, bovine eyes are larger and easier to acquire, and thus have more CECs available. In our study, we acquired the enucleated bovine eyes from a local abattoir. Because of the fresh nature of the bovine eyes, the exact number of bovine CECs harvested is subject to variation, at approximately 1 x 105 cells per eye. By contrast, the number of human CECs in a normal cornea is approximately 3 x 105 per eye. This number is lower in study-grade corneas and is even lower in residual corneal rims after transplantation. Manipulations during the harvesting procedure will further reduce the number of cells obtained. Furthermore, bovine CECs can proliferate and undergo EnMT spontaneously; therefore, the bovine CEC in vitro culture model is useful in investigating the EnMT mechanism and screening EnMT-suppressing chemicals, such as marimastat. Although there remains concern regarding species-related differences, such as the proliferative capacity of CECs, our results demonstrated that the EnMT signaling pathway of bovine CECs is similar to that of human CECs, including the activation of Wnt/β-catenin18,19.

During the isolation of bovine CECs, peeling the Descemet's membrane is critical. In some bovine eyes, the Descemet's membrane may have tight adhesion with the corneal stroma, leading to excessive stromal tissue on the peeled Descemet's membrane. Further trypsinization may lead to the release of stromal keratocytes that transform into corneal fibroblasts, which affect cell purity and therefore the experimental results. In our study, we peeled the Descemet's membrane carefully under a microscope. To further ensure cell purity, we first cultured the harvested cells in a 6 cm dish until cell confluence. Only when the cells were hexagonal in shape were they used in further experiments.

To further substantiate the findings of the bovine CEC in vitro culture model, we used the rat corneal endothelium cryoinjury model adopted in previous studies20,21. After cryoinjury, the rat CECs underwent EnMT during regeneration, manifested by the nuclear translocation of active β-catenin, indicating that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is conserved among species during CEC regeneration. In addition, this model is useful in investigating the function of CECs because low CEC function leads to obvious corneal edema. Combined with other equipments, such as ultrasound biomicroscope, anterior segment optical coherence tomography, and confocal microscopy, corneal thickness can be quantitatively evaluated and thus reflect CEC function.

To stimulate the regeneration of CECs and suppress EnMT after wound healing, we administered intracameral injections of bFGF followed by marimastat injection. The treatment significantly reduced the extent of corneal edema. Previous studies have used the topical application of CEC growth-stimulating agents, such as ROCK inhibitor, and EnMT-suppressing agents, such as Notch inhibitor21,22. However, the penetration of drugs into the CEC layer is limited by the corneal epithelium and stroma, which may influence the treatment efficacy23. In contrast to topical application, intracameral injection enables direct access to the corneal endothelium by introducing drugs directly into the anterior chamber. Therefore, the growth-stimulating and EnMT-suppressing effect of chemicals can be assessed unbiasedly following cryoinjury. In our study, we performed anterior chamber paracentesis to lower the intraocular pressure before intracameral injection. Without paracentesis, an abrupt increase in intraocular pressure causes corneal edema or even prolapse of the iris through the needle tract. Gently compressing the tract during needle withdrawal aids in sealing the wound and preventing intraocular infection.

Disclosures

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Second Core Lab, Department of Medical Research, National Taiwan University Hospital for their technical support.

References

- Maurice DM. The location of the fluid pump in the cornea. J Physiol. 1972;221(1):43–54. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce N. Proliferative capacity of the corneal endothelium. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2003;22(3):359–389. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishige N, Sonoda KH. Bullous keratopathy as a progressive disease: evidence from clinical and laboratory imaging studies. Cornea. 2013;32:77–83. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182a1bc65. Suppl 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates AK, Cheng H, Hiorns RW. Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy: relationship with endothelial cell density and use of a predictive cell loss model. A preliminary report. Curr Eye Res. 1986;5(5):363–366. doi: 10.3109/02713688609025174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SE, Lloyd SA. Epidermal growth factor and its receptor, basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor beta-1, and interleukin-1 alpha messenger RNA production in human corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32(10):2747–2756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KH, Harris DL, Joyce NC. TGF-beta2 in aqueous humor suppresses S-phase entry in cultured corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(11):2513–2519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo T, Obara Y, Joyce NC. EDTA: a promoter of proliferation in human corneal endothelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(10):2930–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue BY, Sugar J, Gilboy JE, Elvart JL. Growth of human corneal endothelial cells in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30(2):248–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peh GS, Beuerman RW, Colman A, Tan DT, Mehta JS. Human corneal endothelial cell expansion for corneal endothelium transplantation: an overview. Transplantation. 2011;91(8):811–819. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182111f01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Rawe I, Joyce NC. Differential protein expression in human corneal endothelial cells cultured from young and older donors. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1805–1814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MK, Kay EP. Regulatory role of FGF-2 on type I collagen expression during endothelial mesenchymal transformation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4495–4503. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HT, Kay EP. FGF-2 induced reorganization and disruption of actin cytoskeleton through PI 3-kinase, Rho, and Cdc42 in corneal endothelial cells. Mol Vis. 2003;9:624–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipparelli A, et al. ROCK Inhibitor Enhances Adhesion and Wound Healing of Human Corneal Endothelial Cells. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e62095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy O, Leclerc VB, Bourget JM, Theriault M, Proulx S. Understanding the process of corneal endothelial morphological change in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):1228–1237. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobiec FA, Bhat P. Retrocorneal membranes: a comparative immunohistochemical analysis of keratocytic, endothelial, and epithelial origins. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(2):230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura N, et al. Involvement of ZEB1 and Snail1 in excessive production of extracellular matrix in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Lab Invest. 2015;95(11):1291–1304. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura N, et al. Enhancement on primate corneal endothelial cell survival in vitro by a ROCK inhibitor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(8):3680–3687. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YT, Chen HC, Chen SY, Tseng SCG. Nuclear p120 catenin unlocks mitotic block of contact-inhibited human corneal endothelial monolayers without disrupting adherent junctions. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(15):3636–3648. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho WT, et al. Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity Reverses Corneal Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(8):2158–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay ED, Cheung CC, Jester JV, Nimni ME, Smith RE. Type I collagen and fibronectin synthesis by retrocorneal fibrous membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982;22(2):200–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, et al. Notch Signal Regulates Corneal Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Am J Pathol. 2013;183(3):786–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura N, et al. The ROCK Inhibitor Eye Drop Accelerates Corneal Endothelium Wound Healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(4):2493–2502. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannermaa E, Vellonen KS, Urtti A. Drug transport in corneal epithelium and blood-retina barrier: emerging role of transporters in ocular pharmacokinetics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58(11):1136–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]