Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a devastating disease with a low five-year survival rate, yet new immunotherapeutic modalities may offer hope for this and other intractable cancers. Here we report that inhibitory targeting of PI3Kγ, a key macrophage lipid kinase, stimulates anti-tumor immune responses, leading to improved survival and responsiveness to standard-of-care chemotherapy in animal models of PDAC. PI3Kγ selectively drives immunosuppressive transcriptional programming in macrophages that inhibits adaptive immune responses and promotes tumor cell invasion and desmoplasia in PDAC. Blockade of PI3Kγ in PDAC-bearing mice reprograms tumor-associated macrophages to stimulate CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor suppression and to inhibit tumor cell invasion, metastasis and desmoplasia. These data indicate the central role that macrophage PI3Kγ plays in PDAC progression and demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ represents a new therapeutic modality for this devastating tumor type.

Keywords: PI3Kγ, PDGF, Arginase, transcription, macrophages, immune suppression, chemotherapy, gemcitabine, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, desmoplasia, metastasis

Introduction

Inflammation plays a major role in cancer immune suppression and progression, perhaps especially in pancreatic cancer (1–4). Ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (PDAC), a devastating disease with one of the poorest five-year survival rates among all cancers, is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in America (5–6). Although 10–15% of patients are candidates for gross total surgical resection, local recurrence and metastasis are frequent, and the overall 5-year survival rate among patients with pancreatic cancer is only around 7% (5–6). Since standard therapies have only a modest impact on survival (7–8), novel therapeutic and diagnostic strategies are urgently needed.

Pancreatic carcinomas, like other solid tumors, are characterized by an abundant inflammatory cell infiltrate, including T cells, B cells, mast cells, macrophages and neutrophils, yet these cells produce an ineffective anti-tumor immune response (9–11). Myeloid lineage cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells and myeloid derived suppressor cells, play important roles in the initiation of pancreatic carcinoma and in establishing an immune suppressive microenvironment that dampens effective anti-tumor T cell responses in pancreatic carcinomas (9–11). Strategies to reverse immune suppression in PDAC by inhibiting myeloid cell trafficking or signal transduction (12–16), by re-activating adaptive immune responses, by vaccination with attenuated intracellular bacteria or DNA plasmids coding for PDAC-associated antigens (16–18), or by the application of checkpoint inhibitors (19–21), have demonstrated that appropriate targeting of the immune system may lead to new and effective treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer. However, continued investigation into the mechanisms by which innate immune cells contribute to PDAC progression will help to refine approaches to improve therapy for this disease.

For this reason, we sought to identify mechanisms regulating the contribution of myeloid cells to immune suppression and progression of PDAC. We report here that the macrophage lipid kinase PI3Kγ promotes immune suppressive polarization in macrophages, leading to immune suppression, tumor progression, metastasis and fibrosis in PDAC. The Class I PI3K lipid kinases phosphorylate PtdIns (4,5)P2 on the 3′ hydroxyl position of the inositol ring to produce PtdIns (3,4,5)P3, which regulates metabolic and transcriptional pathways during inflammation and cancer (22–23). The Class IA isoforms PI3Kα and β are widely expressed in endothelial, epithelial and tumor cells, while the Class IA isoform PI3Kγ is primarily expressed in T and B lymphocytes and the structurally unique Class IB isoform PI3Kγ is expressed mainly in myeloid cells where it is the major PI3K isoform (22–23). PI3Kγ promotes the adhesion and migration of granulocytes and monocytes, and mice lacking the PI3Kγ catalytic subunit, exhibit defects in neutrophil and monocyte accumulation in inflamed and tumor tissues (24–25). Using orthotopic and genetically engineered mouse models of PDAC, we found that inhibition of PI3Kγ unexpectedly slowed PDAC tumor growth and enhanced survival and responsiveness to standard-of-care chemotherapy by altering macrophage transcriptional profiles and thereby activating T cells, indicating that targeting PI3Kγ therapeutically could provide long-term control of this devastating malignancy.

Results

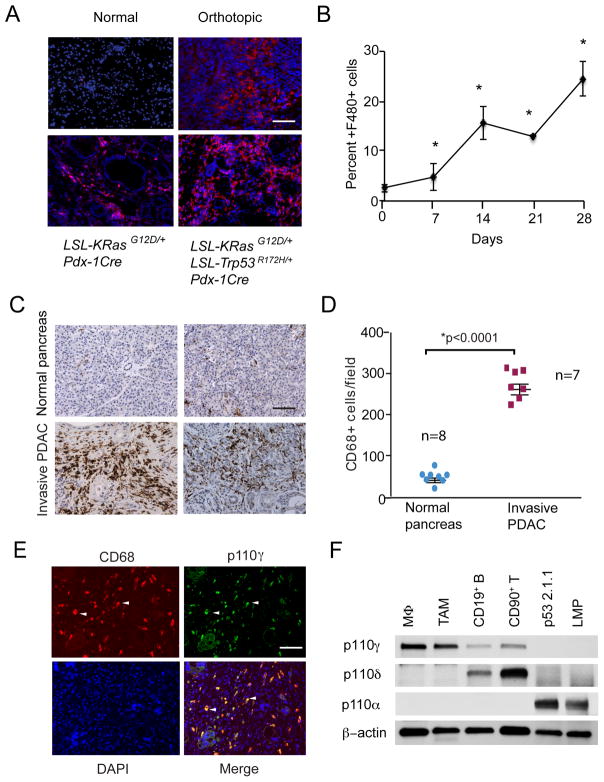

PI3Kγ is a marker of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma associated macrophages

Macrophages play particularly significant roles in PDAC tumor progression, as they can promote tumor initiation, immune suppression and metastasis (9–15). To investigate the role of the macrophage in spontaneous and experimentally induced pancreatic adenocarcinomas, we immunostained pancreata from normal and tumor bearing mice to detect the presence of F4/80+ macrophages. We examined pancreata from normal mice, as well as LSL-KRasG12D; Pdx-1Cre mice (KC mice), which develop extensive PanIns but not invasive carcinoma, LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+; Pdx-1Cre mice (KPC mice), which develop invasive carcinomas and widespread metastases, and orthotopically implanted LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+Pdx-1Cre (LMP) tumors (26–32). While normal pancreata exhibited very few F4/80+ macrophages, pancreata from KC and KPC mice exhibited extensive infiltration by macrophages, as did orthotopic LMP tumors (Fig. 1A). Quantification of CD11b+ myeloid cells and F4/80+ macrophages in spontaneous and orthotopic LMP tumors demonstrated that macrophage infiltration increases, while T cell and B cell infiltration decreases during tumor development (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Figure S1A–D). We also observed increases in CD68+ macrophage content in invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas compared to healthy pancreata from patients (Fig. 1C–D), as has been previously reported (26), indicating that increased macrophage infiltration occurs in both murine and human PDAC.

Figure 1. PI3Kγ is a marker of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma associated macrophages.

A. Immunofluorescent staining of F4/80+ macrophages (red) counterstained with DAPI (blue) in pancreata from normal mice, LSL-KRasG12D; Pdx-1Cre (KC) mice, LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+; Pdx-1Cre (KPC) mice and mice that were implanted orthotopically with LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+Pdx-1Cre (Orthotopic) tumors. Bar indicates 50μm. B. Quantification of the increase in F4/80+ macrophages over time in pancreata that were orthotopically implanted with LMP tumor cells (n=10), *p<0.01. C. Representative histopathologic characterization of human invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissues (n=7) and normal pancreas (n=8) showing immune reactivity for the macrophage marker CD68, with hematoxylin counterstaining. Scale bar indicates 100μm. D. Quantification of CD68+ macrophages/100X microscopic field in tissue sections from normal human pancreata (n=7) and from invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (n=8). Statistical significance was determined via Wilcoxon rank-sum test. E. Immunostaining of human invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas for expression of PI3Kγ (green) and CD68+ macrophages (red). Tissues were counterstained with DAPI (blue) to detect nuclei. Arrows indicate examples of overlap (yellow) of PI3Kγ and CD68 immunostaining. Scale bar indicates 50μm. F. Western blot of p110γ, p110γ, p110α and actin in murine bone marrow derived macrophages (MΦ), tumor associated macrophages (TAM), CD19+ B cells, CD90+ T cells and LMP and p53 2.1.1 murine PDAC cells.

The infiltration of bone marrow derived granulocytes and monocytes into tumors depends in part on the gamma isoform of the Class I PI3K lipid kinases (24–25). Therefore, we asked whether PI3Kγ might promote inflammation associated with tumor progression in PDAC. Immunostaining of clinical biopsies of human invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas to detect expression of PI3Kγ (green) and CD68+ macrophages (red) showed that CD68+ macrophages, but not other cells in pancreatic tumors, uniformly express PI3Kγ (yellow) (Fig. 1E). Western blotting analyses showed that murine bone marrow derived and tumor associated macrophages express PI3Kγ, while CD19+ B cells and CD90+ T cells express PI3Kγ and murine LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53+/−; Pdx-1Cre (p53 2.1.1) and LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+; Pdx-1Cre (LMP, K8484, DT6606, or DT4313) pancreatic carcinoma cells express PI3Kα but not PI3Kγ (Fig. 1F and Supplementary Fig. S2A). These results indicate that PI3Kγ is a biomarker of PDAC-associated macrophages that might have a functional role in PDAC inflammation.

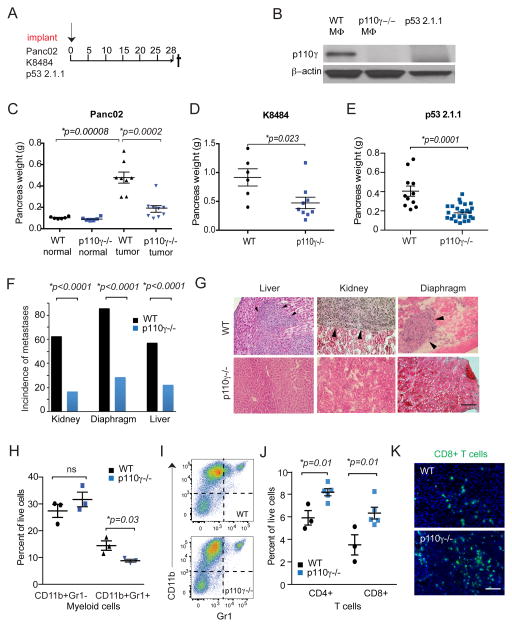

PDAC tumor growth and metastasis depend on macrophage PI3Kγ

To investigate the functional role of macrophage PI3Kγ in pancreatic cancer, Panc02, K8484, or p53 2.1.1 pancreatic tumor cells were orthotopically implanted in wild type or PI3Kγ deficient (p110γ−/−;) mice, according to the depicted schema (Fig. 2A). Whereas WT macrophages expressed PI3Kγ, neither p110γ−/−; macrophages nor PDAC cells expressed this kinase (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 2A). While normal p110γ−/−; pancreata were similar in size as those from WT mice, pancreatic tumors from p110γ−/−; mice were significantly smaller than pancreatic tumors in WT mice, as p110γ−/− tumors were reproducibly half the size of WT tumors (Fig. 2C–E). Notably, the incidence of PDAC metastases, including kidney, diaphragm and liver metastases, was also significantly reduced in p110γ−/− animals (Fig. 2F–G), indicating that macrophage PI3Kγ contributes to tumor spread.

Figure 2. PDAC tumor growth and metastasis depend on macrophage PI3Kγ.

A. Panc02, K8484 or p53 2.1.1 PDAC tumor cells were orthotopically implanted into syngeneic WT or p110γ−/− mice according to the depicted schema. B. Western blot comparing p110γ and actin expression in WT and p110γ−/− macrophages and in vitro cultured p53 2.1.1 PDAC cells. C–E. Weights of normal pancreata as well as pancreata containing tumors from WT and p110γ−/− mice 28 days after orthotopic implantation with (C) Panc02, (D) K8484 or (E) p53 2.1.1 PDAC cells. Significance testing was performed by nonparametric t test. F. Incidence of kidney, diaphragm and liver metastases in WT and p110γ−/− animals implanted with Panc02 cells. Significance testing was performed by Fisher’s exact test. G. Images of kidney, diaphragm and liver metastases from F. Arrowheads indicate metastatic foci. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. H. Quantification of CD11b+Gr1− macrophages and CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells by flow cytometry in representative tumors from WT (n=3) and p110γ−/− (n=5) mice. Significance testing was performed by unpaired t test. I. Representative Facs plots from WT and p110γ−/− orthotopic tumors. J. Quantification of CD4 and CD8 T cells in tumors from WT (n=3) and p110γ−/− (n=5) mice. Significance testing was performed by unpaired t test. K. Immunofluorescence images of CD8+ T cells in WT and p110γ−/− tumors. Scale bar indicates 50μm.

We previously showed that PI3Kγ regulates the trafficking of bone marrow-derived CD11bGr1lo monocytes and CD11bGr1hi granulocytes into lung tumors by stimulating integrin α4β1 mediated adhesion to endothelium (24–25, 33). To determine if PI3Kγ regulates myeloid cell trafficking in pancreatic tumors, we performed flow cytometry to quantify immune cell populations in tissues from PDAC-bearing p110γ−/− vs WT animals and in PI3Kγ inhibitor vs vehicle control-treated animals. Whereas PI3Kγ inhibition only slightly suppressed recruitment of CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells to tumors, it had little effect on the recruitment of CD11b+Gr1-F480hi macrophages into PDACs (Fig. 2H–I; Supplementary Fig. S2B). Importantly, PDACs from p110γ−/− mice exhibited significantly more CD4+ and CD8+ T cell content than PDACs from WT mice (Figure 2J–K). In contrast, no differences were observed in the number of T cells in spleen, lung or liver of p110γ−/− and WT mice (Supplementary Fig. S2C–D). As p110γ is primarily expressed in myeloid cells, and p110γ is the major isoform PI3K isoform in T cells (Figure 1F), these results suggest that PI3Kγ inhibition in myeloid cells promotes enhanced CD8+ T cell mobilization into PDACs, thereby enhancing anti-tumor immunity.

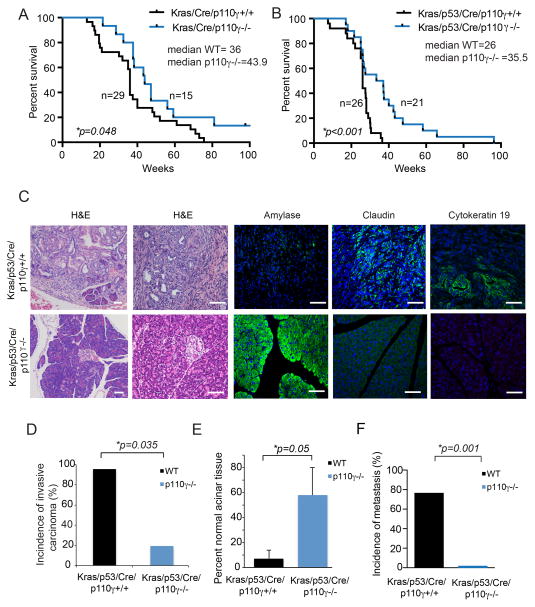

Genetic ablation of PI3kγ improves survival in mice with pancreatic adenocarcinomas

To determine whether PI3Kγ inhibition improves the survival of mice with spontaneous pancreatic tumors, we crossed PI3Kγ−/− mice with KC and KPC mice (27–28). PI3Kγ deletion significantly delayed tumor progression and extended the survival of both KC and KPC mice (Fig. 3A–B). The median survival time of control KC mice was 36 weeks, while median survival of p110γ−/− KC mice was 43.9 weeks (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the median survival time of control KPC animals was 26 weeks while the median survival time of p110γ−/− KPC animals was 35.5 weeks (Fig. 3B). Remarkably, twenty percent of p110γ−/− KPC mice lived for more than one year, whereas none of the WT mice survived beyond 40 weeks. Analysis of pancreata from KPC animals by immunohistochemistry indicated that most KPC animals exhibited extensive claudin+, cytokeratin19+ invasive carcinoma (30) with little normal amylase+ pancreas remaining (Fig. 3C–E). WT animals almost uniformly exhibited metastases in organs that included liver, heart, lung and kidney (Fig. 3F). In contrast, KPC; p110γ−/− animals exhibited extensive areas of normal amylase+ pancreas, little claudin+ and cytokeratin19+ invasive carcinoma (Fig. 3C–E), and little evidence of metastasis (Fig. 3F). Together, these results illustrate that PI3Kγ drives tumor development and spread in the pancreas and whereas PI3Kγ inhibition prevents these events and significantly extends survival.

Figure 3. PI3Kγ inhibition promotes survival of mice with PDAC.

A. Kaplan-Meier plot of survival of KC mice (n=29; median survival=36 weeks) compared to KC;p110γ−/− mice (n=15; median survival=43.9 weeks). B. Kaplan-Meier plot of survival of KPC animals (n=26; median survival=26 weeks) compared to KPC; p110γ−/− mice (n=21; median survival=35.5 weeks). Significance testing was performed by parametric Student’s t test. C. Images of hematoxylin and eosin staining and fluorescence immunostaining to detect amylase, claudin and cytokeratin 19 in tissue sections of pancreata tissue harvested at sacrifice in B. Images representative of the group are shown. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. D. Incidence of invasive carcinoma in animals from B. Significance testing was performed by Fisher’s exact test. E. Percent normal acinar tissue in animals from B. F. Incidence of metastasis in animals from B. Significance testing was performed by Fisher’s exact test.

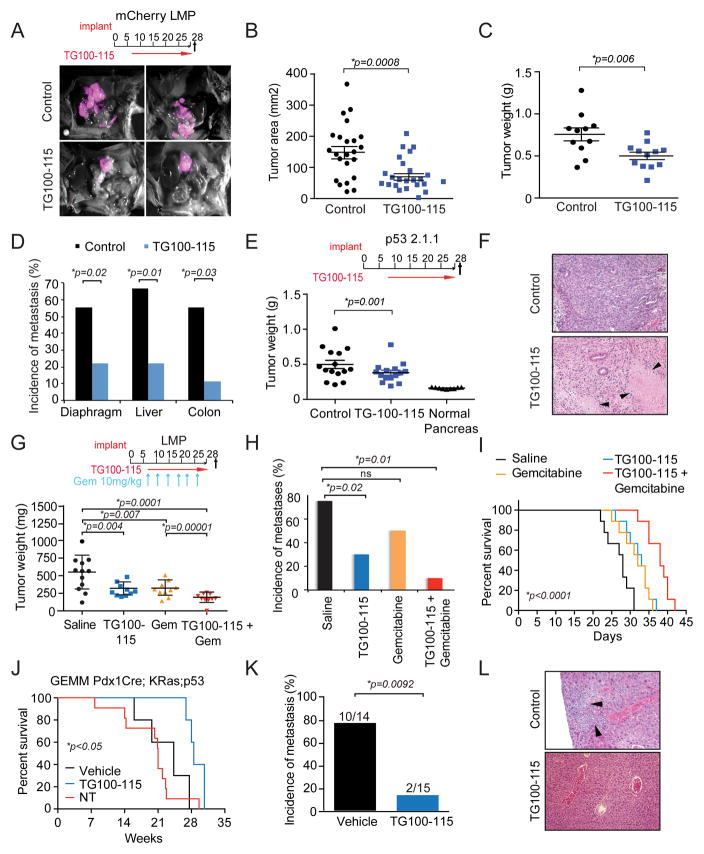

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ suppresses PDAC growth and metastasis

Since PI3Kγ promotes PDAC growth and spread, we speculated that pharmacological inhibitors of PI3Kγ could favorably impact the outcome of pancreas cancer. To test this, we evaluated the effect of the investigational PI3Kγ/γ inhibitor TG100–115, which has an IC50 of 83nM for p110γ, 238nM for p110γ and >1000nM for p110α and p110β (34), in mouse models of PDAC. mCherry-labeled LMP cells were orthotopically implanted into the pancreata of WT mice, and mice were then treated with the PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100–115 or chemically matched control compound, according to the schema depicted in Figure 4A. Intravital imaging revealed that control-treated mice exhibited large pancreatic tumors and multiple metastases, whereas TG100–115 treated mice had significantly smaller pancreatic tumors and few, if any metastases (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S3A–B). Quantification of tumor size by area of fluorescence and by tumor weight demonstrated that TG100–115 substantially suppressed PDAC growth to approximately half of that of control treated animals (Fig. 4B–C). TG100–115 also quantitatively suppressed metastasis to the diaphragm, liver, colon and other organs (Fig. 4D). Either early or late treatment with TG100–115 suppressed growth of p53 2.1.1 orthotopic tumors (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Fig. 4A–C), indicating PI3Kγ inhibition can suppress the growth of late stage tumors as well as early stage tumors. Histological analysis of tumors revealed that TG100–115 treated tumors exhibited enhanced tumor necrosis compared to control treated tumors (Fig. 4F); however, TG100–115 had no direct affect on viability of any PDAC cell line (Supplementary Fig. S4D–E). As PI3Kγ inhibition suppresses tumor growth without directly targeting tumor cells, these results suggested that PI3Kγ inhibitors might effectively combine with standard of care chemotherapy, which targets tumor cells directly.

Figure 4. Pharmacological inhibitors of PI3Kγ suppress PDAC growth and metastasis.

A. Merged brightfield and red fluorescent images of mCherry-labeled LMP orthotopic pancreatic tumors from mice that were treated with PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100-115 or chemically similar control according to the schema depicted. B. Mean area of fluorescence from A. C. Mean weight of pancreata from A. D. Incidence of metastases in animals from A. E. Weight of normal pancreas and TG100-115 and control treated p53 2.1.1 orthotopic tumors. F. Images of tumors from TG100-115 and control treated animals from E. Arrows indicate necrotic tissue. G. Weight of PDAC tumors from animals treated with saline, TG100-115, gemcitabine and gemcitabine+TG100-115 according to the depicted schema. Significance testing was performed by one-sided Anova with Tukey’s posthoc multiple pairwise testing. H. Incidence of metastases in animals from G. Significance testing was performed by Fisher’s exact test. I. Effect of TG100-115 (n=9; median survival = 33 days), gemcitabine (n=9; median survival = 32 days) and combination gemcitabine + TG100-115 treatment (n=9; median survival = 38 days) on survival of implanted PDAC tumors compared to control treated animals (n=9; median survival = 28 days). J. Kaplan-Meier survival plot of KPC animals that were treated from week 10 to week 25 with TG100-115 (n=5; median survival = 28.5 weeks) compared to control treated KPC (n=5; median survival = 21 weeks) and untreated KPC mice (n=11; median survival= 24.3 weeks). K. Incidence of metastasis in TG100-115 (n=15) treated and control treated KPC animals (n=14). Significance testing was performed by Fisher’s exact test. L. Images of metastases in liver cross sections from control and TG100-115 treated tumors from K. Significance testing was performed by Anova or unpaired t-test.

To evaluate the combinatorial effect of PI3Kγ inhibition and chemotherapy on PDAC growth and progression, we treated mice bearing orthotopic PDAC tumors with TG100–115 and gemcitabine, according to the depicted schema (Fig. 4G). TG100–115 and gemcitabine similarly suppressed tumor growth as single agents, while the combination of the two treatments even further suppressed tumor growth (Fig. 4G) and significantly inhibited metastasis (Fig. 4H). Importantly, combined TG100–115 and gemcitabine treatment prolonged survival of mice with implanted PDACs from a median survival of 28 days for control animals to 38 days for the combination of Gemcitabine and TG100–115 (Fig 4I). Additionally, long-term TG100–115 treatment significantly increased survival of KPC mice with spontaneous pancreatic tumors and was accompanied by substantial reductions in metastasis (Fig. 4J–L). These results indicate that PI3Kγ inhibitors provide long-term survival benefits in these models of pancreas cancer.

PI3Kγ drives macrophage polarization and immune suppression in vitro and in vivo

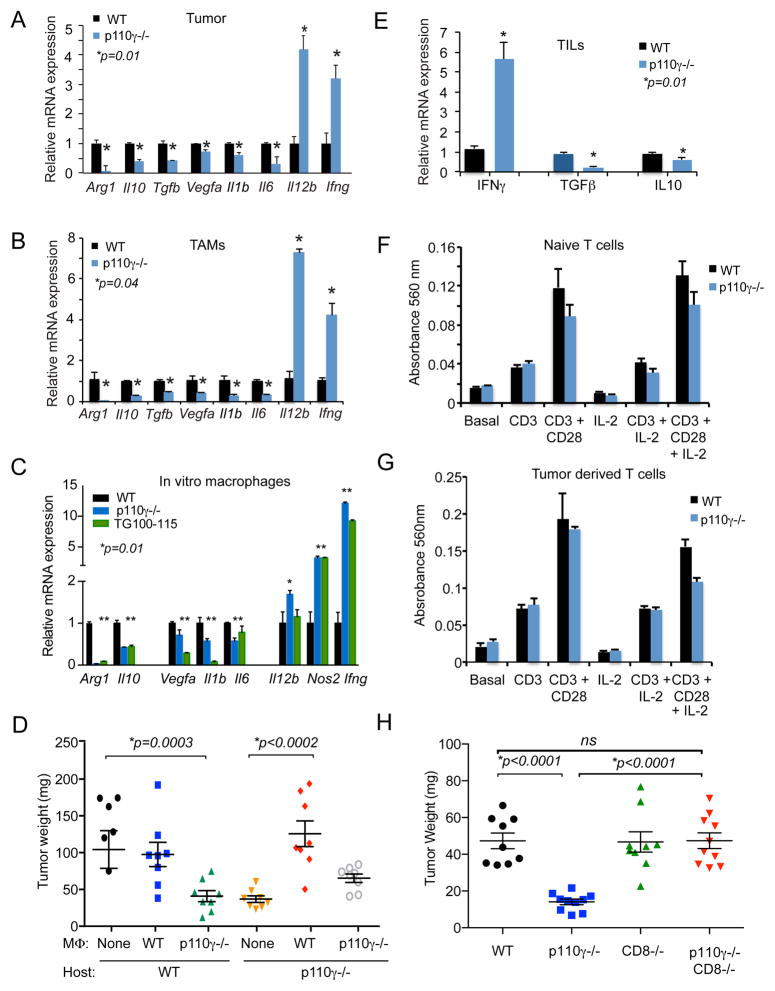

Although myeloid cells can establish immunosuppressive microenvironments by inhibiting CD8+ T cell recruitment and/or survival in tumors (9–11), p110γ−/− PDACs exhibited increased CD8+ cell influx (Fig 2J–K). Therefore, we investigated whether PI3Kγ inhibition alters the immune response expression profile of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. The expression of genes associated with immune suppression, chronic inflammation or tumor angiogenesis, including Arg1, Tgfb, Il1b, Il6 and Vegfa, were strongly expressed in myeloid cells isolated from WT PDAC tumors (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Genetic (p110γ−/−) and pharmacological (TG100–115) inhibition of PI3Kγ both significantly inhibited expression of these genes in orthotopic PDAC tumors and in TAMs purified from PDAC tumors (Fig. 5A–B, Supplementary Fig. S5B–C). In contrast, the expression of immunostimulatory factors, including Il12 and Ifng, was significantly enhanced in tumors and TAMs from p110γ−/− and PI3Kγ inhibitor-treated animals (Fig. 5A–B, Supplementary Fig S5B–C). However, no significant difference in gene expression was observed in macrophages isolated from the uninvolved spleen or liver of WT and p110γ−/− PDAC tumor bearing mice (Supplementary Fig S5D–E). To determine whether PI3Kγ directly controls these transcriptional changes in macrophages, we evaluated the effect of PI3Kγ inhibition in IL-4 polarized in vitro cultured macrophages, which model tumor derived macrophages, as they express immune-suppressive cytokines and factors, including Arg1, Il10 and Tgfb, and inhibit expression of immune stimulatory genes including Il12b and Ifng (35–39). Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ not only inhibited immunosuppressive gene expression but also stimulated expression of Il12b, Ifng and Nos2 (Fig. 5C), indicating that PI3Kγ directly regulates a macrophage transcriptional switch from immune suppression toward immune stimulation.

Figure 5. PI3Kγ drives tumor associated macrophage polarization and immune suppression in vitro and in vivo.

A–B. Relative mRNA expression of immune response genes in (A) orthotopic WT and p110γ−/− Panc02 tumors and (B) purified TAM from orthotopic WT and p110γ−/− Panc02 tumors. C. Relative mRNA expression of immune response genes in p110γ−/− or TG100-115 and control treated in vitro macrophages that were polarized with IL-4 for 48h. *p<0.05. D. Mean weight of tumors from WT or p110γ−/− mice implanted with p53 2.1.1 tumor cells admixed 1:1 with macrophages isolated from p53 2.1.1 tumors grown p110γ−/− and WT mice (n=8). Significance testing was performed by one-way Anova with Tukey’s posthoc multiple pairwise testing. E. mRNA expression of Ifng, Tgfb and Il10 in T cells isolated from orthotopic WT and p110γ−/− Panc02 tumors. F–G. In vitro proliferation of anti-CD3, anti-CD3+CD28 or IL2 + anti-CD3+ CD28 treated T cells isolated from spleens of (F) naive mice or (G) p53 2.1.1 PDAC tumor bearing mice. H. p53 2.1.1 tumor growth in WT, p110γ−/−, CD8−/−, and p110γ−/−;CD8−/− animals (n=10). Significance testing was performed by one-way Anova with Tukey’s posthoc multiple pairwise testing.

To determine if selective blockade of PI3Kγ in macrophages was sufficient to disrupt tumor growth, we performed adoptive transfer studies by implanting tumor-derived macrophages in tumors grown in WT host mice. Tumor derived macrophages were isolated from WT and p110γ−/− p53 2.1.1 tumors, mixed with freshly cultured p53 2.1.1 tumor cells and implanted in WT or p110γ−/− host mice. Tumor growth was significantly inhibited when p110γ−/− macrophages were implanted in either WT or p110γ−/− host mice (Fig. 5D). In contrast, tumor growth was enhanced when WT macrophages were implanted in p110γ−/− host mice (Fig. 5D). Importantly, tumors implanted with p110γ−/−, but not WT, macrophages exhibited a three-fold increase in CD8+ T cell content (Supplementary Fig. S5F).

Our studies show that PI3Kγ inhibition alters macrophage transcriptional programming, leading to increased CD8+ T cell recruitment and reduced PDAC growth (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S5F). We speculated therefore, that PI3Kγ inhibition indirectly activates T cell mediated anti-tumor immune responses in vivo. Accordingly, we found that T cells isolated from p110γ−/− PDAC tumors exhibited enhanced expression of the TH1 cytokine Ifng and downregulated expression of the immune suppressive cytokines Tgfb and Il10 (Fig. 5E). To exclude the possibility that PI3Kγ within T cells directly controls T cell activation, we examined the effect of p110γ inhibition on T cell proliferation ex vivo. T cells were isolated from naive (Fig. 5F) or PDAC-bearing (Fig. 5G) WT and p110γ−/− mice, and proliferation was stimulated by incubation with anti-CD3, anti-CD3+CD28 or IL2 + anti-CD3+CD28 antibodies. No differences were observed in the proliferative capacity of WT and p110γ−/− T cells, whether from naive or tumor-bearing mice. To determine if the anti-tumor effect of p110γ inhibition required the presence of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, we crossed WT and p110γ−/− mice with CD8−/− animals and performed PDAC tumor studies. As only 3% of live cells in WT PDACs were CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2J), it was not surprising that CD8 deletion had little effect on WT PDAC tumor size (Fig 5H). Importantly, CD8 deletion ablated the tumor suppressive effect of p110γ inhibition (Fig. 5H). Taken together, these results indicate that macrophage PI3Kγ suppresses T cell mediated immune surveillance by promoting expression of immunosuppressive cytokines by tumor associated macrophages. Furthermore, our studies indicate that PI3Kγ inhibition indirectly stimulates T cell mediated anti-tumor immune responses, leading to growth suppression in PDAC.

Recent progress in anti-cancer therapeutics has led to the development and clinical approval of T cell checkpoint inhibitors for therapy of some solid tumors, including melanoma and lung carcinoma (18–21). To explore the possibility that PI3Kγ inhibitors might synergize with T cell checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of PDACs, we first evaluated expression of the programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and its ligand, programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in WT and p110γ−/− PDAC tumors. Although PD-1 was expressed on CD8+ T cells from PDAC tumors, we observed no significant differences in expression levels in T cells from WT and p110γ−/− tumors (Supplementary Fig. S6A). We did observe significant expression of the checkpoint ligand PD-L1 on macrophages but not tumor cells from PDACs but no difference in expression between cells from WT and p110γ−/− tumors (Supplementary Fig. S6B). We also observed no change in the presence of FoxP3+CD25+CD4+ T regulatory cells in WT and p110γ−/− tumors (Supplementary Fig. S6C). To explore the relative effects of PI3Kγ inhibition and T cell checkpoint inhibition as therapeutic strategies, we treated WT and p110γ−/− animals bearing PDAC tumors with anti-PD-1 or isotype control antibodies. Both anti-PD-1 and p110γ inhibition substantially suppressed PDAC tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. S6D–E). However, the combination of anti-PD-1 with p110γ inhibition provided no added benefit over single agent therapy (Supplementary Fig. S6D–E). We also treated WT animals bearing PDAC tumors with TG100-115, anti-PD-1, isotype control antibodies or combination therapy; similarly no benefit was observed with the combined treatment. These data support the conclusion that PI3Kγ inhibition promotes an anti-tumor T cell response that, like anti-PD-1, relieves T cell exhaustion. Future studies optimizing checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy and tumor cell targeted therapy in combination with PI3Kγ inhibition may provide further insights into the nature of immune suppression in PDAC cancer.

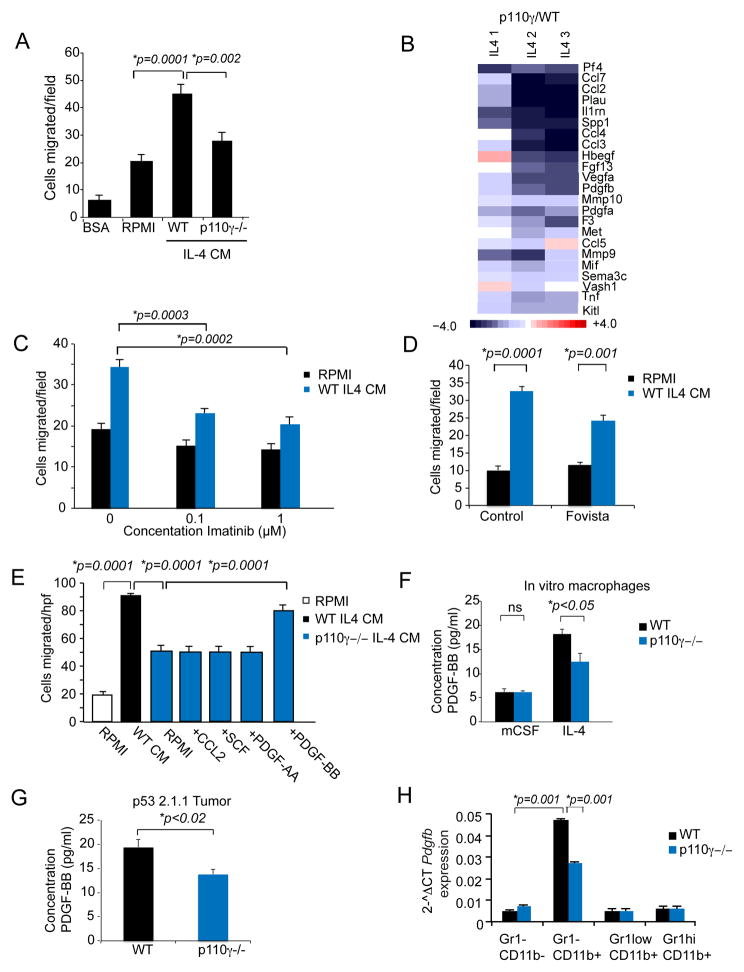

PI3Kγ controls macrophage PDGF expression to promote PDAC cell invasion

PI3Kγ inhibition mediated a striking suppression of metastasis in orthotopic and spontaneous PDAC models (Fig. 2–4). To determine whether macrophage PI3Kγ promotes PDAC invasion, we analyzed the effect of conditioned medium (CM) from IL-4 stimulated WT or p110γ−/− macrophages on migration of LMP and p53 2.1.1. PDAC cells. CM from WT macrophages stimulated robust chemotaxis, while CM from p110γ−/− macrophages was less effective in stimulating cell migration (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Fig. S7A). Macrophage CM had no effect on cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S7B). To identify factors that could account for these differences in migration, we performed RNA sequencing on p110γ −/−; and WT IL-4 stimulated macrophages and found that the mRNA expression of many chemotactic factors, including Ccl2, Scf, Hbegf, Pdgfa, and Pdgfb, was strongly suppressed in p110γ−/− macrophages (Fig. 6B). To determine if these factors could stimulate PDAC invasion, we tested the effect of the PDGFR inhibitor Imatinib (40–41), the PDGF inhibitor Fovista (42), the EGFR inhibitors Erlotinib (43), Lapatinib (44) and anti-CCL2 on CM stimulated chemotaxis. Only Imatinib and Fovista suppressed PDAC migration toward macrophage CM, indicating that PDGF and PDGFR are required for macrophage stimulated PDAC chemotaxis (Fig. 6C–D and Supplementary Fig. S7C–D). To determine which cytokines were sufficient to induce migration, we supplemented p110γ −/− CM with PDGF-AA, PDGF-BB, SCF or CCL2 and found that only PDGF-BB was sufficient to restore chemotactic migration in murine and human PDAC cells (Fig. 6E; Supplementary Fig. S7E–F). Notably, we found that PDGF-BB protein expression was reduced in p110γ−/− CM and in PDAC tumors from p110γ−/− mice (Fig. 6F–G). As p110γ−/− CD11b+Gr1− tumor derived macrophages expressed reduced PDGFβ mRNA in vivo (Fig. 6H), our studies show that macrophage derived PDGF-BB may promote PDAC metastasis in vivo and that PI3Kγ inhibitors may block metastasis by suppressing macrophage expression of PDGF-BB.

Figure 6. PI3Kγ controls macrophage PDGF expression to promote PDAC tumor cell invasion.

A. Chemotaxis of LMP PDAC cells towards conditioned medium from IL-4 stimulated WT or p110γ−/− macrophages (IL-4 CM). B. Relative mRNA expression of select chemotactic factors in IL-4 stimulated p110γ−/− vs WT macrophages as determined by RNA sequencing and expressed as Log2-fold change from WT. C. Chemotaxis of LMP PDAC cells towards conditioned medium from IL-4 stimulated WT macrophages (WT IL4 CM) or RPMI medium in the presence or absence of dilutions of the PDGFR inhibitor Imatinib. D. Chemotaxis of LMP PDAC cells towards RPMI or conditioned medium from IL-4 stimulated WT macrophages (WT IL4 CM) in the presence or absence of the PDGF inhibitor Fovista. E. Chemotaxis of LMP PDAC cells towards medium (RPMI) or conditioned medium from IL-4 stimulated WT or p110γ −/− macrophages in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml CCL2, SCF, PDGF-AA or PDGF-BB. F. Concentration of PDGF-BB in conditioned medium from WT and p110γ−/− basal (mCSF-stimulated) and IL-4 stimulated macrophages. G. Concentration of PDGF-BB in lysates from p53 2.1.1 orthotopic pancreatic tumors grown in WT and p110γ−/− mice. H. Relative mRNA expression of Pdgfb in tumor-derived CD11b+Gr1− macrophages, CD11b+Gr1lo monocytes, CD11b+Gr1hi neutrophils and CD11b−Gr1− cells (tumor cells). Significance testing was performed by Anova or parametric Student’s t test.

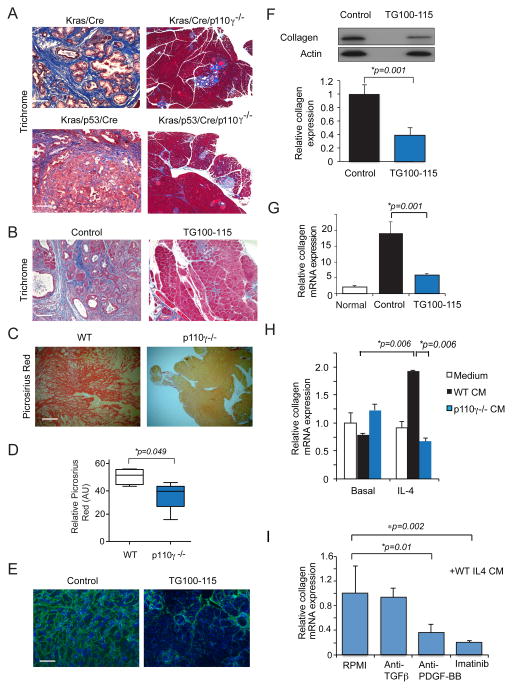

PI3Kγ mediated macrophage PDGF-BB expression promotes desmoplasia in PDAC

Pancreatic tumors are associated with extensive desmoplasia; this severe desmoplastic response impedes the effectiveness of chemotherapy and disrupts the normal functions of the pancreas (45). Pancreata from p110γ−/− KC and KPC animals exhibited substantially less desmoplasia than their WT counterparts, as revealed by Masson’s Trichrome staining of pancreatic tumor sections (Fig. 7A). Similarly, pancreata from KPC animals treated with the PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100-115 exhibited less desmoplasia by Trichrome staining (Fig. 7B). Similar differences in desmoplastic response were seen in picrosirius red stained pancreata from KPC orthotopic tumors grown in WT and p110γ−/− animals (Fig. 7C–D). Additionally, less collagen protein and gene expression was observed in orthotopic LMP tumors that were treated with the PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100-115 (Fig. 7E–G). To determine whether macrophage PI3Kγ regulates fibroblast-mediated collagen expression, we incubated primary murine fibroblasts with CM from basal and IL-4 stimulated WT and p110γ−/− macrophages. Less collagen mRNA was expressed in fibroblasts incubated with p110γ−/− CM (Figure 7H). As p110γ−/− macrophages express less TGFβ1 and PDGF-BB than WT macrophages, we tested the effect of inhibitors of these factors in collagen expression assays. Only anti-PDGF-BB and Imatinib suppressed collagen expression in fibroblasts, indicating that macrophage PI3Kγ likely regulates desmosplasia associated with PDAC by controlling expression of secreted PDGF-BB (Fig. 7I).

Figure 7. PI3Kγ promotes macrophage PDGF-BB expression to control PDAC fibrosis.

A. Masson’s Trichrome staining of tissue sections of pancreata from WT and p110γ−/− KC and KPC animals. Scale bar, 100μm. B. Masson’s Trichrome staining of sections of pancreata from control and TG100-115 treated KPC animals. C–D. Images (C) and quantification (D) of picrosirius red staining of sections of pancreata from KPC tumors grown in WT and p110γ−/− animals. Scale bar 100μm. E. Collagen I immunostaining of LMP tumors from animals treated with the PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100-115 or chemically similar inert control. F. Western blot and quantification of collagen I protein expression in LMP tumors from animals treated with the PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100-115 or chemically similar inert control. G. Relative collagen I mRNA expression in normal pancreata and LMP tumors from animals treated with the PI3Kγ inhibitor TG100-115 or chemically similar inert control. H. Relative collagen I mRNA expression in primary murine fibroblasts incubated in the presence or absence of stimulus free conditioned medium from IL-4 stimulated WT and p110γ−/− macrophages. I. Relative collagen I mRNA expression in fibroblasts incubated in the presence or absence of stimulus free conditioned medium from IL-4 stimulated WT macrophages in the absence or presence of anti-TGFβ, anti-PDGF-BB or Imatinib. Significance testing was performed by parametric Student’s t test.

In summary, the studies presented here demonstrate the critical roles that PI3Kγ plays in regulating PDAC tumor growth and progression. Our studies demonstrate PI3Kγ promotes transcription of genes associated with the M2 immunosuppressive macrophage phenotype in PDACs, including immune suppressive factors such as Arg1, Tgfb, and Il10 and chemokines and wound healing factors that include PDGF-BB. By inhibiting PI3Kγ, the expression of these genes is constrained, thereby activating CD8+ T cell dependent tumor suppression and increased survival.

Discussion

Inflammation plays a critical role in pancreatic carcinoma progression and relapse from therapy (1–4). B cells, T cells and myeloid cells can all be found in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment, yet these cells do not mount an appropriate anti-tumor adaptive immune response. It is now accepted that tumor associated macrophages and myeloid derived suppressor cells release immune suppressive factors that inhibit T cell mediated anti-tumor responses (3, 38), and therapeutic approaches that are aimed at preventing myeloid derived suppressive responses show some therapeutic efficacy in animal models of cancer (12–17). T cell checkpoint inhibitors that target T cell functions in cancer also hold some promise as novel therapeutics for pancreatic cancer (18–21). However, strategies that inhibit myeloid cell-mediated immune suppression may well boost the effect of checkpoint inhibitors, vaccines and other therapeutic strategies in the highly immunosuppressive microenvironment of pancreatic tumors.

In the studies presented here, we have identified PI3Kγ as a critical regulator of the pathways that control immune suppression, metastasis and desmoplasia in pancreatic cancer. We showed that PI3Kγ is expressed in human and murine pancreatic tumor macrophages and that selective deletion of this PI3K isoform suppresses orthotopic and spontaneous PDAC growth and metastasis. In addition, PI3Kγ inhibition significantly enhanced survival of mice bearing spontaneous PDACs by suppressing tumor growth and metastasis. Our studies demonstrate that PI3Kγ plays a key role in activating the immune suppressive transcriptional signature of tumor derived macrophages, in that PI3Kγ inhibition suppressed expression of Arg1, Tgfb, and Il10 and stimulated expression of Il12 and Ifng in vivo. These changes in myeloid gene expression signatures were associated with increased CD8+ T cell recruitment to PDAC tumors, increased T cell expression of IFNγ and decreased expression of TGFβ and IL10, and CD8+ T cell dependent tumor suppression. Our results are in agreement with recent studies that showed that PI3Kγ but not PI3Kγ is required for T cell activation but contrast with studies that showed that p110γ is required for T cell recruitment by inflammatory chemokines (46–49). It is possible that T cell recruitment to tumors in vivo depends on chemokines that only activate p110γ rather than p110γ. Finally, we show that PI3Kγ also regulates macrophage expression of PDGF-BB, which stimulates tumor cell chemotaxis and fibroblast production of collagen in vitro and in vivo. Recent studies revealed that p53 mutations induce constitutive PDGFR expression and signaling that drives tumor invasion and metastasis (50). Our studies suggest that macrophage derived PDGF-BB may cooperate with this mutant pathway to promote metastasis but also show that targeting PI3Kγ can control this pathway by which PDACs spread. Our studies thus demonstrate that inhibitors of PI3Kγ offer promise as new therapeutic approaches to control tumor growth and progression, metastasis and desmoplasia in this devastating malignancy.

In related studies, we demonstrated that human and murine PDACs exhibit increased PI3Kγ-dependent BTK activation in CD11b+ FcγRI/III+ myeloid cells (51). BTK or PI3Kγ inhibition as monotherapy in early stage PDAC, or in combination with Gem in late-stage PDAC slowed progression of orthotopic tumors in a manner dependent on T cells (51). However, we observed that BTK was not activated in p110γ−/− macrophages and that combination of BTK and PI3Kγ inhibitors had no additive effects in regulating macrophage gene expression or PDAC progression. These studies indicated that the two kinases regulate overlapping signal transduction pathways in macrophages. An increase in effector and memory CD8+ T cell phenotypes was also observed in these studies, which is consistent with other reports about CD8+ T cell responses to various immunotherapies (17).

We demonstrated that genetic and pharmacological PI3Kγ inhibition was as effective as treatment with the checkpoint inhibitor anti-PD-1 in mouse models of PDAC. Although we were unable to observe additive effects of targeting PI3Kγ and PD-1 on tumor growth at this time, we did observe improved survival by combining PI3Kγ inhibitors and chemotherapeutic agents. Our studies show that targeted inhibition of PI3Kγ can combine with other therapeutic approaches targeting distinct components of the tumor microenvironment to effect long-term durable anti-PDAC tumor immune responses.

Methods

Institutional approvals

All studies with human tissues were approved by the Institutional Review Board for human subjects research of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to surgery. The use of samples occurred under “exempt category 4” for research on de-identified biological specimens. All animal experiments were performed with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of California, San Diego and the University of Torino, Italy.

Reagents

TG100-115 was from Targegen, Inc. (La Jolla, CA). Fovista was from Ophthotech (New York, NY).

Cell lines

The p53 2.1.1 pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line was derived from primary PDAC tumors (Fvb/N) of male transgenic KC mice harboring null mutations in p53. The LMP pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line was derived from a liver metastasis of a primary PDAC tumor from transgenic KPC mice in a C57Bl6;129Sv background. The K8484 pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line was derived from a primary PDAC tumor from transgenic KPC mice in a C57Bl6 background. The Panc02 cell line from C57Bl6 mice has been previously described (33). All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma contamination and grown in DMEM/10% FBS/1.0% Pen-Strep on plastic plates (LMP, Panc02, K8484) or plastic plates coated with 50μg/ml rat tail collagen I (p53 2.1.1)(BD Biosciences). Cells used in these studies were authenticated by morphological profiling and RNA sequencing and RT-PCR in 2012, whole exome analysis in 2015 (p53 2.1.1), and PI3Kγ inhibitor sensitivity analyses (2013–2015). Panc02 cells and LMP were acquired in 2009; K8484 cells and p53 2.1.1 cells were acquired in 2014.

Animals

Generation and characterization of p110γ−/−, KC and KPC mice have been described previously (23–24, 29). KPC animals in the C57Bl6 background were crossed with Pik3cg−/− animals in the C57Bl6 background to generate Pik3cg−/−KC; and Pik3cg−/−; KPC mice in the Animal Facility at the Molecular Biotechnology Center, University of Turin.

Tumor studies

Ten thousand p53 2.1.1 PDAC cells were orthotopically implanted into the pancreata of p110γ+/+ (WT) or p110γ−/− 8–10 week old FVB/n mice. Five hundred thousand LMP PDAC cells were orthotopically implanted into the pancreata of 8–10 week old C57Bl6;129 mice and five hundred thousand K8484 or Panc02 PDAC cells were orthotopically implanted into the pancreata of 8–10 week old C57Bl6 mice (n=10). In some studies, WT and p110γ−/− animals with tumors were treated by i.p injection with and without gemcitabine (150 mg/kg) on d7 and d14 (n=10). In other studies, mice were treated by i.p injection b.i.d. with 2.5mg/kg of PI3Kγ inhibitor (TG100–115) or with a chemically similar inert control twice daily from day 7–21 (n=10). In some studies, WT and p110γ−/− mice were treated with 100μg anti-PD-1 or isotype control clone LTF-2, (BioXCell) administered by i.p. injection on day 7, 10 and 13 of tumor growth. Mice were sacrificed on d21. For all tumor experiments, tumor volumes and weights were recorded at sacrifice. In other studies, the growth, metastasis and survival of spontaneous PDAC tumors in p110γ+/+ and p110γ−/− LSL-KRasG12D/+; Pdx-1/Cre, and LSL-KRasG12D/+; LSL-Trp53R172H/+Pdx-1Cre animals was evaluated over 100+ weeks.

RNA sequencing

Freshly isolated mouse bone marrow cells from 9 WT and 9 p110γ−/− mice were pooled into 3 replicates sets of WT or p110γ−/− cells that were differentiated into macrophages for six days in RPMI + 20% FBS+ 1%Pen/Strep+ 50 ng/ml M-CSF. Each replicate set of macrophages was then incubated for 48 h with mCSF or mCSF + IL-4. Macrophages were removed from dishes, and RNA was harvested using Qiagen Allprep kit. One microgram of total RNA per sample was used for the construction of sequencing libraries. RNA sequencing was performed by the University of California, San Diego Institute for Genomic Medicine Genomics Center as follows: RNA libraries were prepared for sequencing using standard Illumina protocols. mRNA profiles of MCSF and IL4 stimulated macrophage derived from wild-type (WT) and PI3Kinase gamma null (p110γ−/−) mice were generated by single read deep sequencing, in triplicate, using Illumina HiSeq2000. Sequence analysis was performed as previously described and results are available to view online at the NCBI Gene Express Omnibus website (file number GSE58318).

Statistics

For studies evaluating the effect of drugs on tumor growth, a sample size of at least 10 mice/group provided 80% power to detect mean difference of 2.25 standard deviation (SD) between two groups (based on a two-sample t-test with 2-sided 5% significance level). Prior to statistical analyses, data were examined for quality and possible outliers. Data were normalized to the standard where applicable. Significance testing was performed by one-way Anova with Tukey’s posthoc testing for multiple pairwise testing or by parametric or nonparametric Student’s t test as appropriate. Fisher’s exact test was used to query significant differences in rates of metastasis between groups.

Supplementary methods

Additional detailed methods are available online in Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

We report here that PI3Kinase gamma (PI3Kγ) regulates macrophage transcriptional programming leading to T cell suppression, desmoplasia and metastasis in pancreas adenocarcinoma. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ restores anti-tumor immune responses and improves responsiveness to standard-of-care chemotherapy. PI3Kγ represents a new therapeutic immune target for pancreas cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ophthotech for the gift of Fovista and Sanofi-Aventis/Targegen for the gift of TG100-115. The authors also thank Xiaodan Song, Joan Manglicmot and Roberta Curto for technical assistance.

Grant support: The authors acknowledge support from T32HL098062 to MMK and R01CA167426-03S1 to AVN; from Ministero della Salute Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata RF-2013-02354892, Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (5 x mille no. 12182) and (IG no. 15257); University of Turin-Progetti Ateneo 2014-Compagnia di San Paolo (PANTHER to PC) (PC-METAIMMUNOTHER) to FN and support from the NCI/NIH (R01CA167426, R01CA126820 and R01CA083133), Lustgarten Foundation and AACR/Landon Foundation to JAV.

Footnotes

Author contributions: MMK, CH and PS performed IHC analysis. MMK, CH, PF, PC and MCS performed orthotopic PDAC models. EM, MMK, MCS and PC performed PDAC GEMM studies. MMK and CH performed Western blotting. MMK, AVN, NR, CH, SG, PF and MCS performed RT-PCR. Cell migration studies were performed by AVN and MMK. Collagen expression analysis was performed by AVN and MMK. MV provided human pancreas tissues and pathological analysis. RS performed RNA seq data analysis. MB, AL and JAV directed studies at UCSD. FN and EH directed studies at University of Torino. JAV, MB, AML, FN and EH conceived the studies. JAV wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts: None

References

- 1.Liou GY, Storz P. Inflammatory macrophages in pancreatic acinar cell metaplasia and initiation of pancreatic cancer. Oncoscience. 2015;2:247–51. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, Combs C, Tuveson DA, Vonderheide RH. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9518–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karakhanova S, Link J, Heinrich M, Shevchenko I, Yang Y, Hassenpflug M, et al. Characterization of myeloid leukocytes and soluble mediators in pancreatic cancer: importance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e998519. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2014.998519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty GL, Winograd R, Evans RA, Long KB, Luque SL, Lee JW, et al. Exclusion of T Cells From Pancreatic Carcinomas in Mice Is Regulated by Ly6C(low) F4/80(+) Extratumoral Macrophages. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:201–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SEER.cancer.gov [Internet] Rockville: National Cancer Institute; c2015. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, Laheru DA, Smith LS, Wood TE, et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and Therapeutic Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:462–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid MC, Varner JA. Myeloid cells in tumor inflammation. Vasc Cell. 2012;4:14. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coussens LM, Zitvogel L, Palucka AK. Neutralizing tumor-promoting chronic inflammation: a magic bullet? Science. 2013;339:286–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1232227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stortz P. The crosstalk between acinar cells with Kras mutations and M1-polarized macrophages leads to initiation of pancreatic precancerous lesions. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1008794. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1008794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stromnes IM, Brockenbrough JS, Izeradjene K, Carlson MA, Cuevas C. Targeted depletion of an MDSC subset unmasks pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to adaptive immunity. Gut. 2014;63:769–81. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612–16. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y, Knolhoff BL, Meyer MA, Nywening TM, West BL, Luo J. CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating macrophages and improves response to T-cell checkpoint immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5057–69. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu NJ, Armstrong TD, Jaffee EM. Nonviral oncogenic antigens and the inflammatory signals driving early cancer development as targets for cancer immunoprevention. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1549–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappello P, Rolla S, Chiarle R, Principe M, Cavallo F, Perconti G, et al. Vaccination with ENO1 DNA prolongs survival of genetically engineered mice with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1098–106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keenan BP, Saenger Y, Kafrouni MI, Leubner A, Lauer P, Maitra A, et al. A Listeria vaccine and depletion of T-regulatory cells activate immunity against early stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms and prolong survival of mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1784–94. e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E, et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520:373–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune Checkpoint Blockade: A Common Denominator Approach to Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martini M, De Santis MC, Braccini L, Gulluni F, Hirsch E. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and cancer: an updated review. Ann Med. 2014;46:372–383. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.912836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanhaesebroeck B, Stephens L, Hawkins P. PI3K signalling: the path to discovery and understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:195–203. doi: 10.1038/nrm3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmid MC, Avraamides CJ, Dippold HC, Franco I, Foubert P, Ellies LG, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinases and TLR/IL1Rs unexpectedly activate myeloid cell PI3Kgamma, a single convergent point promoting tumor inflammation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:715–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid MC, et al. PI3-kinase gamma promotes Rap1a-mediated activation of myeloid cell integrin alpha4beta1, leading to tumor inflammation and growth. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng L, Guo Y, Liang J, Chen S, Peng P, Zhang Q, et al. Perineural Invasion and TAMs in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas: Review of the Original Pathology Reports Using Immunohistochemical Enhancement and Relationships with Clinicopathological Features. J Cancer. 2014;5:754–60. doi: 10.7150/jca.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuveson DA, Shaw AT, Willis NA, Silver DP, Jackson EL, Chang S, et al. Endogenous oncogenic K-ras(G12D) stimulates proliferation and widespread neoplastic and developmental defects. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:375–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bardeesy N, Aguirre AJ, Chu GC, Cheng KH, Lopez LV, Hezel AF, et al. Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5947–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601273103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins MA, Benar F, Zhang Y, Brisset J-C, Galban S, Galban CJ, et al. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:639–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins MA, Brisset J-C, Zhang Y, Bednar F, Pierre J, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer is dependent on oncogenic Kras in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng WW, Winer D, Kenkel JA, Choi O, Shain AH, Pollack JR, et al. Development of an orthotopic model of invasive pancreatic cancer in an immunocompetent murine host. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3684–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid MC, Avraamides CJ, Foubert P, Shaked Y, Kang SW, Kerbel RS, et al. Combined blockade of integrin-alpha4beta1 plus cytokines SDF-1alpha or IL-1beta potently inhibits tumor inflammation and growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6965–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palanki MS, Dneprovskaia E, Doukas J, Fine RM, Hood J, Kang X, et al. Discovery of 3,3′-(2, 4-diaminopteridine-6,7-diyl)diphenol as an isozyme-selective inhibitor of PI3K for the treatment of ischemia reperfusion injury associated with myocardial infarction. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4279–4294. doi: 10.1021/jm051056c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, Schioppa T, Saccani A, Sironi M, et al. A distinct and unique transcriptional program expressed by tumor-associated macrophages (defective NF-kappaB and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation) Blood. 2006;107:2112–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flavell RA, Sanjabi S, Wrzesinski SH, Licona-Limon P. The polarization of immune cells in the tumour environment by TGFbeta. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:554–67. doi: 10.1038/nri2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barron L, Smith AM, El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Huang X, Cheever A, et al. Role of arginase 1 from myeloid cells in th2-dominated lung inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J, Ortiz B, Zea AH, Piazuelo MB, et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5839–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Pesce JT, Smith AM, Thompson RW, Henao-Tamayo M, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.George D. Platelet-derived growth factor receptors: a therapeutic target in solid tumors. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joensuu H, Dimitrijevic S. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) as an anticancer agent for solid tumours. Ann Med. 2001;33:451–5. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tolentino MJ, Dennrick A, John E, Tolentino MS. Drugs in Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24:183–99. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.961601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim TE, Murren JR. Erlotinib OSI/Roche/Genentech. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:1385–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia W, Mullin RJ, Keith BR, Liu LH, Ma H, Rusnak DW, et al. Anti-tumor activity of GW572016: a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks EGF activation of EGFR/erbB2 and downstream Erk1/2 and AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2002;21:6255–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi C, Washington KM, Chaturvedi R, Drosos Y, Revetta FL, Weaver CJ, et al. Fibrogenesis in pancreatic cancer is a dynamic process regulated by macrophage-stellate cell interaction. Lab Invest. 2014;94:409–21. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alcazar I, Marques M, Kumar A, Hirsch E, Wymann M, Carrera AC, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma participates in T cell receptor-induced T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2977–2987. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin AL, Schwartz MD, Jameson SC, Shimizu Y. Selective regulation of CD8 effector T cell migration by the p110 gamma isoform of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Immunol. 2008;180:2081–2088. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali K, Soond DR, Pineiro R, Hagemann T, Pearce W, Lim EL, et al. Inactivation of PI(3)K p110delta breaks regulatory T-cell-mediated immune tolerance to cancer. Nature. 2014;510:407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature13444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soond DR, Bjørgo E, Moltu K, Dale VQ, Patton DT, Torgersen KM, et al. PI3K p110delta regulates T-cell cytokine production during primary and secondary immune responses in mice and humans. Blood. 2010;115:2203–2213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weismueller S, Manchado E, Saborowski M, Morris J, Wagenblast E, Davis CA, et al. Mutant p53 drives pancreatic cancer metastasis through cell-autonomous PDGF Receptor β signaling. Cell. 2014;157:382–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gunderson AJ, Kaneda MM, et al. Bruton Tyrosine Kinase–Dependent Immune Cell Cross-talk Drives Pancreas Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:270–285. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.