Abstract

Genome sizes in plants vary over several orders of magnitude, reflecting a combination of differentially acting local and global forces such as biases in indel accumulation and transposable element proliferation or removal. To gain insight into the relative role of these and other forces, ∼105 kb of contiguous sequence surrounding the cellulose synthase gene CesA1 was compared for the two coresident genomes (AT and DT) of the allopolyploid cotton species, Gossypium hirsutum. These two genomes differ approximately twofold in size, having diverged from a common ancestor ∼5–10 million years ago (Mya) and been reunited in the same nucleus at the time of polyploid formation, ∼1–2 Mya. Gene content, order, and spacing are largely conserved between the two genomes, although a few transposable elements and a single cpDNA fragment distinguish the two homoeologs. Sequence conservation is high in both intergenic and genic regions, with 14 conserved genes detected in both genomes yielding a density of 1 gene every 7.5 kb. In contrast to the twofold overall difference in DNA content, no disparity in size was observed for this 105-kb region, and 555 indels were detected that distinguish the two homoeologous BACs, approximately equally distributed between AT and DT in number and aggregate size. The data demonstrate that genome size evolution at this phylogenetic scale is not primarily caused by mechanisms that operate uniformly across different genomic regions and components; instead, the twofold overall difference in DNA content must reflect locally operating forces between gene islands or in largely gene-free regions.

The lack of correlation between genome size and organism complexity, known as the “C-value paradox” (Thomas 1971) or “G-value/N-value paradox” (Claverie 2000; Bertran and Long 2002), has been recognized for more than half a century (Mirsky and Ris 1951). Genome size in eukaryotes varies >200,000-fold, from ∼2.8 Mb in Encephalitozoon cuniculi (Biderre et al. 1998) to >690,000 Mb in the diatom Navicola pelliculosa (Cavalier-Smith 1985; Li and Graur 1991). Even within various eukaryotic groups, there are remarkable differences in genome size. Protozoans display a 5800-fold genome size variation, vertebrates a 330-fold variation, and angiosperms display a 2300-fold variation in genome size (Cavalier-Smith 1985; Gregory 2001; Bennett and Leitch 2003). Significant genome size variation has also been observed among closely related species; for instance, the plant genus Crepsis displays a ninefold variation (Jones and Brown 1976), whereas another plant genus, Vicia, displays a sixfold variation in genome size (Chooi 1971). Despite this impressive variation in genome size, the amount of variation in the numbers of protein coding genes is only about 20-fold (Li 1997).

Although it is generally agreed that the majority of genome size variation can be accounted for by differences in the amount of noncoding DNA, the relative importance of mechanisms that generate genome size variation is not well-understood. In plants, the most prominent forces involved in genomic expansion are acknowledged to be polyploidy (Wendel 2000) and transposable element (TE) amplification (Bennetzen 2002), complemented by smaller-scale processes such as increases in pseudogene number (Zhang 2003), intron size (Deutsch and Long 1999; Vinogradov 1999), and incorporation of organellar genome fragments into the nucleus (Adams and Palmer 2003; Shahmuradov et al. 2003). Taken alone, these forces would cause an upward spiral toward bloated genomes (Bennetzen and Kellogg 1997). This one-way ticket to obesity is contraindicated by the phylogenetic distribution of plants with smaller genomes (Bennett and Leitch 1995, 1997; Leitch et al. 1998; Wendel et al. 2002b), as well as by the existence of many plants, such as Arabidopsis (Vision et al. 2000) and maize (Ilic et al. 2003), that clearly have eliminated massive amounts of DNA following polyploidization. Less well understood are evolutionary mechanisms that reduce genome size. Global mechanisms, such as small indel (<400 bp) mutational bias (Petrov 2002b) and species-specific differences in nonhomoeologous end joining (Kirik et al. 2000; Orel and Puchta 2003), have the potential to stochastically and differentially contract genomes. Sequence-specific mechanisms, such as LTR recombination (Shirasu et al. 2000; Vitte and Panaud 2003), ectopic recombination (Langley et al. 1988; Bennetzen 2000b; Petrov et al. 2003), and illegitimate recombination (Devos et al. 2002; Ma et al. 2004), have been shown to be capable of removing larger segments of DNA. Superimposed on these internal molecular genetic mechanisms are external factors and selective forces that may mold genome size; cell size limitations and cell division rate selection, for example, may constrain genome size (Gregory 2002).

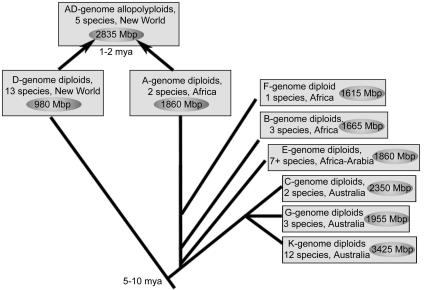

Some mechanisms of genome size evolution, such as polyploidy and global deletional biases, are expected to affect all genomic constituents approximately equally, whereas others, such as proliferation of transposable elements, are likely to be more heterogeneous in their impacts on various genomic regions. To evaluate these alternatives, it may be informative to compare closely related species that differ dramatically in genome size. Here we demonstrate this approach using model species from the genus Gossypium. Despite its relatively young age (5–10 million years old; Cronn et al. 2002) and conserved complement of genes, DNA content varies more than threefold within the genus, from 980 to 3425 Mb per 1C nucleus (Wendel and Cronn 2003). Two diploid groups of species, designated A-genome and D-genome, diverged from a common ancestor about 5–10 million years ago (Mya) and acquired genomes that differ approximately twofold in size. Approximately 1–2 Mya, these two genomes became reunited in a common nucleus through allopolyploidization, leading to the evolution of the modern polyploid cotton species, including Gossypium hirsutum, the primary cotton of commerce. Backed by a well-studied phylogeny (Fig. 1), we have embarked on comparative BAC sequencing to illuminate the patterns and processes responsible for modern-day genome size differences. For our initial study, we compared 100 kb+ of homoeologous sequence surrounding a cellulose synthase gene (CesA1) from the two genomes (designated AT and DT) that comprise the allotetraploid, G. hirsutum, and that differ overall in genome size by a factor of 2 (1C = 980 Mb and 1860 Mb for DT and AT, respectively; Endrizzi et al. 1985). Remarkably, sequence conservation between the AT and DT genomes is shown to be high, even in intergenic regions. No evidence of mechanisms that underlie the twofold genome size difference is observed within this genomic region, where even the >550 small indels detected are evenly divided among the two genomes. The results show that genome size evolution operates regionally rather than globally at this phylogenetic scale, perhaps largely between gene islands.

Figure 1.

The evolutionary history of diploid and tetraploid Gossypium, as inferred by numerous chloroplast and nuclear data sets (Seelanan et al. 1997; Small et al. 1998; Cronn et al. 2002). Genome groups designate closely related species, as determined by interspecific meiotic pairing and chromosome size (Endrizzi et al. 1985). All diploid species have the same base chromosome number (n = 13); however, each genome group varies in genome size (1C content indicated in circles). Polyploid species are thought to have originated 1–2 Mya, following divergence of their diploid progenitors 5–10 Mya.

RESULTS

General Sequence Comparison of the Homologous BACs

The CesA1 BACs from the AT and DT genomes were shotgun-sequenced and assembled, giving a total of 2311 sequence reads and 4019 sequence reads, respectively. The overall gapped, aligned length of AT with DT is 123.8 kb. The ungapped aligned length of the AT BAC is 103.9 kb, and the ungapped aligned length of the DT BAC is 107.9 kb. Thus, for the CesA1 region in G. hirsutum, there is only a 4-kb difference in length between the AT and DT genomes. Both BACs are equal in GC content (33% GC). Database searches led to the inference of 14 genes in the CesA1 region, shared by both genomes. The total length of these genes was calculated to be 29.2 kb, or about one-third of the sequence. Excluding the 555 gapped positions (see below), which collectively exclude 36 kb and distinguish the two homoeologs, sequence identity over the aligned, ungapped positions was extraordinarily high (95%).

Analysis of Potential Genes

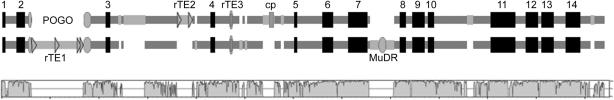

Fourteen genes were predicted along the colinear segment (Fig. 2), giving an average density of 1 gene per 7.5 kb of sequence. This is slightly less than the average Arabidopsis gene density of 1 gene per 4.5 kb of sequence (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000) and similar to the average gene density in rice (Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium 2003). The CesA1 region appears to be part of a gene island, as the gene density is fairly high and the non-genic DNA content low. The predicted genes (Table 1) range in size from a partial 244-bp fragment of a putative ABC-transporter to 4.3 kb in a predicted gene that is similar to an expressed Arabidopsis protein (gi: 18396997). Silent and replacement site substitutions were calculated for each gene (Table 1). Synonymous substitution rates between homoeologous genes vary over a 10-fold range, from 0.008 to 0.084, with a weighted mean of 0.037; this value is identical to the weighted mean of 0.037 that was previously reported for a set of ∼40 homoeologous genes in polyploid Gossypium (Senchina et al. 2003).

Figure 2.

Pairwise alignment of CesA1 homoeologous BACs, AT and DT, to scale. AT and DT are genes shown as block diagrams: numbered boxes are predicted corresponding to the list presented in Table 1; rTE1, rTE2, and rTE3 represent the three largely intact retrotransposons identified (rTE1 encompasses two predicted copia elements); the POGO and MuDR-like TEs are indicated individually, as is the ycf2 fragment of plastidial origin. The bottom panel indicates a continuous window of sequence identity between the two BACs, scaled from 50% to 100%.

Table 1.

Gene Features Predicted Along Homoeologous AT and DT BACs Surrounding the CesA1 Gene in Allopolyploid Cotton

|

Length (bp)b

|

Total length, exonsb

|

Total length, introns

|

Length (a.a.)

|

Divergencec

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Putative functiona | DT | AT | Exons | DT | AT | Introns | DT | AT | DT | AT | Ks | Ka | Ksil | |

| 1 | ABC transporterd | 244 | 244 | * | 244 | 244 | * | 0 | 0 | 81 | 81 | 0.035 | 0.000 | 0.035 | |

| 2 | GTP-binding protein | 1909 | 1925 | 2 | 657 | 657 | 1 | 1252 | 1268 | 218 | 218 | 0.054 | 0.006 | 0.047 | |

| 3 | WRKY TF | 1024 | 1013 | 3 | 822 | 819 | 2 | 202 | 194 | 273 | 274 | 0.064 | 0.014 | 0.041 | |

| 4 | Arabidopsis hypothetical protein | 994 | 992 | 3 | 471 | 471 | 2 | 523 | 521 | 156 | 156 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.061 | |

| 5 | No BLAST homoeology | 519 | 519 | 1 | 519 | 519 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 172 | 172 | 0.084 | 0.026 | 0.084 | |

| 6 | G-protein B | 2376 | 2376 | 9 | 1068 | 1068 | 8 | 1308 | 1308 | 355 | 355 | 0.043 | 0.012 | 0.029 | |

| 7 | CesA | 4080 | 4083 | 12 | 2925 | 2925 | 11 | 1155 | 1158 | 974 | 974 | 0.041 | 0.004 | 0.033 | |

| 8 | LeuRR | 1308 | 1308 | 1 | 1308 | 1308 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 435 | 435 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.020 | |

| 9 | PRR/Se-binding protein | 2628 | 2628 | 3 | 2418 | 2418 | 2 | 210 | 210 | 805 | 805 | 0.019 | 0.013 | 0.018 | |

| 10 | Ribosomal protein L11 | 1273 | 1275 | 4 | 519 | 519 | 3 | 754 | 756 | 172 | 172 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.029 | |

| 11 | LeuRR transmembrane or kinase | 3189 | 3197 | 11 | 1857 | 1857 | 10 | 1332 | 1340 | 618 | 618 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.031 | |

| 12 | Growth regulator | 2631 | 2637 | 10 | 1797 | 1800 | 9 | 834 | 837 | 598 | 599 | 0.050 | 0.015 | 0.037 | |

| 13 | Permease | 2633 | 2629 | 13 | 1575 | 1575 | 12 | 1058 | 1054 | 524 | 524 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.021 | |

| 14 | Arabidopsis expressed protein | 4349 | 4325 | 8 | 1287 | 1278 | 7 | 3062 | 3047 | 425 | 422 | 0.037 | 0.014 | 0.029 | |

| Weighted average | 0.037 | 0.010 | 0.032 | ||||||||||||

Putative function is assigned by BLAST homoeology to genes in GenBank. The locations of genes along the BAC contigs are represented in Figure 2.

Total length including stop codon.

Ks, Ka, and Ksil denote rate of substitution across all sites, substitutions at nonsynonymous sites, and synonymous sites within codons plus all noncoding positions, respectively.

This predicted gene is fragmented in the BAC; a start codon was identified, but no intronic sequences or stop codon was found. This gene would presumably be full length, were it not fragmented in the generation of the BAC library. An asterisk (*) signifies that the number of exons and introns is not known.

We searched a growing collection of cotton EST data sets for evidence of transcription of the predicted genes. To date, ∼150,000 ESTs have been generated from various tissues and organs of diploid and polyploid cotton (J.A. Udall, J. Hatfield, R.A. Rapp, Y. Wu, L. Dennis, A.B. Arapat, T. Wilkins, J. Guo, X. Chen, E. Taliercio et al., unpubl.). Searches of these data sets revealed evidence for expression of five of the 14 genes inferred to reside on the CesA1 BACs. This, in addition to the sequence divergence evidence and low levels of replacement substitutions (Table 1), lends support to the gene predictions.

Analysis of Potential Transposable Elements

Differential insertions of transposable elements (TEs) are recognized as a prominent force in genome size expansion. Thus, we examined the CesA1 BACs for evidence of transposable elements. A total of six largely intact TEs were detected in the two G. hirsutum homoeologs, two that are shared, one that is unique to AT, and three that are unique to DT. The two genomes also share a highly degraded EnSpm (class 2) remnant, identified by CENSOR (Jurka et al. 1996), as well as a potential and highly degraded retrotransposon, identified by BLAST homoeology to elements characterized in an ongoing study (J.S. Hawkins, H-R. Kim, R.A. Wing, J.D. Nason, and J.F. Wendel, unpubl.). The AT genome has a series of potential, highly degraded retrotransposons of indeterminate number, again identified by BLAST homoeology. Additionally, nine potential miniature inverted-repeat TEs (MITEs) were predicted in the CesA1 region, seven shared between AT and DT, and two that are unique to AT. Overall, transposable elements (including remnants) account for 28.5 kb of sequence in the region, 10.8 kb in AT, and 17.7 kb in DT.

The two shared intact transposable elements belong to different classes. One of the shared transposable elements has similarity to known POGO elements from Arabidopsis. The putative POGO is flanked by 15-bp terminal inverted repeats (TIR), which have 73% identity (5′-TIR vs. 3′-TIR) and which retain the typical TA dinucleotide target site duplication. Each Gossypium POGO element retains ∼90% identity over the TIR to several Arabidopsis POGO elements (Feschotte and Mouches 2000) and 35% identity over the entire element. Compared with each other, the AT POGO (1940 bp) and the DT POGO (2150 bp) have 83% sequence identity, including gaps, and 92% sequence identity when gaps are excluded.

The other shared intact transposable element is a retrotransposon of unidentified type. This element was identified through its BLASTX identity to known reverse transcriptase (RT) sequences (40% identity and 65% similar over 100 amino acids to numerous RT sequences from Arabidopsis). There is evidence that this RT sequence may have been derived from a degraded non-LTR retroelement, as a few BLASTX hits were to non-LTR RT sequences and no vestige of ancient LTRs was identified.

The AT and DT genomes also share what appears to be a 45-bp remnant of a highly degraded EnSpm transposon. This remnant was identified by CENSOR as having identity to the described EnSpm element ATENSPM5 from Arabidopsis (Jurka 2000). Sequence identity between AT and DT over the remnant is 100%, and the sequence identity between either Gossypium remnant and ATENSPM5 is 82%.

Finally, the AT and DT genomes also share a potential, highly degraded gypsy retrotransposon. The DT element shows 164 bp identity to Gossypium gypsy elements, whereas 204 bp of identity was observed for the AT element.

The AT BAC sequence contains only one identified largely intact transposable element that is not shared with the DT genome. This element is a predicted long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposon of unknown type. The element contains 612-bp LTRs, which retain 98% sequence identity with each other. The element is 3138 bp in length and contains homoeology to identified tomato (gi: 4235644) and Arabidopsis pol proteins of unspecified type.

The AT BAC sequence contains two potential and extremely degraded retroelement clusters. The first retroelement cluster spans 7.5 kb of sequence, although only 1573 bp can be identified as belonging to degraded TEs. This cluster may have contained two to three gypsy elements, one shared with the DT BAC sequence (204 bp; mentioned above), and contains moderate sequence identity (60%–70%) to previous reported A-genome-specific repetitive sequences (Zhao et al. 1998). The second degraded retroelement cluster contains a potential gypsy remnant and a potential copia remnant. These two remnants are situated on either side of a cpDNA insertion (see below), and were likely genomic neighbors before being separated by the cpDNA insertion.

The DT BAC contains three transposable elements (one DNA element and two copia retrotransposons) that are not shared with the AT genome. The DNA element has homoeology to several Oryza mutator (MuDR) elements, as well as some limited homoeology to the Arabidopsis Vandal12 DNA element (Jurka et al. 1996). The element appears to be degraded, as the protein alignment generated by BLASTX shows only 26% identity (44% similarity) over 536 amino acids.

The two copia insertions that are DT-specific for this BAC are nested within the POGO insertion (see Fig. 3). The outer copia has 200-bp LTRs that are 97% identical. The element is 5.3 kb in length and has well-defined reverse transcriptase-, integrase-, and protease-coding domains. The inner copia has 561-bp LTRs that are 99.7% identical. This element also is 5.3 kb in length and has well-defined reverse transcriptase- and integrase-coding domains. The protease-coding domain for this element could not be identified. The inner copia inserted between the protease-coding domain and LTR of the outer copia, after the outer one had inserted. These copia insertions share no identity with each other; thus, they probably belong to different families. Retrotransposon insertions can be dated based on LTR divergence (SanMiguel et al. 1998), although these estimates provide only approximations, given the unknown absolute rate of mutation. Previous data on sequence divergence in Gossypium (Senchina et al. 2003) can be used to infer the relative insertion times of each copia. The percent divergence between LTRs of the outer copia (3%) is similar to that estimated for divergence of A- and D-genome diploids, suggesting transposition shortly after the divergence of these two species groups. Similarly, LTR divergence of the inner copia (0.3%) is slightly less than that estimated for comparisons between model diploid progenitors and their counterparts in the polyploid, suggesting insertion of the internal copia subsequent to polyploidization.

Figure 3.

Nested insertions of retroelements in the AT BAC of Gossypium hirsutum. The outer copia is shown in gray and the inner copia in black. Four LTRs, corresponding to the two copia insertions, are shown as triangles. The three coding domains of the copias, reverse transcriptase (RT), integrase (INT), and protease (PRO), are designated by the labeled boxes within the LTRs. Surrounding the copia nest is a single POGO element that is shared by AT and DT, and which was split in two when the copias inserted.

Miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) are a common feature of gene-rich regions (Feschotte et al. 2002). Although they are categorized as class 2 elements, these nonautonomous TEs do not encode a transposase or transposase remnant; thus, the prediction and classification of potential MITEs is primarily achieved through terminal inverted repeat (TIR) and target site duplication (TSD) identification (Feschotte et al. 2002). Considering this, two approaches were used to predict MITEs in the AT and DT CesA BACs. The first approach, which attempted to predict MITEs from known families (Stowaway, Tourist, etc.) by searching for similarity to TIRs from known MITEs in Arabidopsis, Brassica, and the grasses, did not reveal any known MITEs in the CesA BACs. The second approach used a de novo search method (Tu 2001), which inspects the sequence for potential TIRs that also have a TSD. Although this method predicted many MITEs in both AT and DT, subsequent inspection revealed that a majority of the predicted TIRs and TSDs contained simple sequence repeats (SSRs). Predicted MITEs whose TIRs were comprised mostly of SSRs were considered probable artifacts. In total, 16 MITEs were predicted in the CesA1 region, seven shared and two unique to AT, accounting for 2.5 kb and 2 kb in AT and DT, respectively.

Other Potential Mechanisms of Genome Size Evolution

In addition to TE insertions, the CesA1 BAC alignments were examined for other distinctions. Most prominent among these is a 900-bp fragment of the plastid gene ycf2, which was inserted into a noncoding region of the AT genome (Fig. 2; 90% identity over 897 bp to ycf2 from Arabidopsis) and was flanked by 1.5 kb of AT-specific sequence of undetermined identity. While accounting for a mere 0.86% of the total aligned length of the homoeologous BACs, the 900-bp ycf2 fragment accounts for 5.6% of the AT-specific sequence.

Intron sizes for each gene were compared for all inferred genes on the homoeologous BACs to evaluate their potential contribution to the genome size variation. Intron sizes deviated by an average of 4.3 bp per gene, with a range of 0–16 bp. The total contribution of intron size differences to the size difference of the region was a mere gain of 3 bp in AT. This result provides a striking contrast to reports of intron sizes contributing to genome size differences over much longer evolutionary timescales (Deutsch and Long 1999; Vinogradov 1999). The present study concurs with previous data on Gossypium intron size variation, which suggested that there exists little intron size variation among Gossypium species, irrespective of genome size (Wendel et al. 2002a).

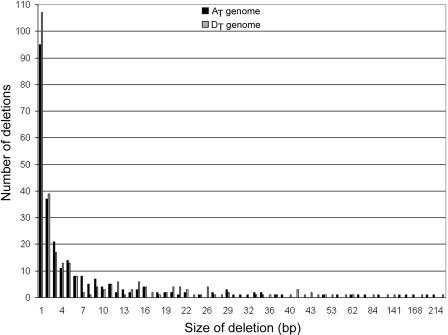

Evidence for a bias in small indel number and length was also examined for the homoeologous sequences (Fig. 4; Table 2). The frequency of small indels was computed for any gapped position <400 bp in length. A total of 555 small gaps were scored in the two BACs, approximately equally distributed between AT and DT in number and aggregate size. Of the 269 indels in AT and 286 indels in DT, 264 and 279 were classified as small indels, respectively. Moreover, small indels account for 2777 bp of missing sequence in AT and 2897 bp of missing sequence in DT, a difference of only 120 bp. In addition to similarities in number and aggregate size, the frequency spectrum of small indels is similar in shape and position between the AT and DT BACs; that is, the number of indels of any length is similar between AT and DT (Fig. 4). Overall, small indels account for 14% and 18% of the total length in AT and DT, respectively, but fail to contribute significantly to the overall size difference in the aligned region.

Figure 4.

The spectrum of small indels inferred from sequence alignment of the AT and DT CesA1 BACs. For AT (solid bars), “differences” are gapped positions relative to DT, whereas for DT (open bars), differences reflect gaps relative to AT. These indels are not although the phylogenetically polarized, spectrum of indels is equivalent in the two genomes.

Table 2.

Spectrum of Small Indelsa in the Comparison Between AT and DT Homoeologous BACs of Gossypium hirsutum

|

AT Genome

|

DT Genome

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of indels | bp | No. of indels | bp | |

| 1-10 bp | 210 | 593 | 207 | 489 |

| 11-20 bp | 25 | 369 | 34 | 506 |

| 21-30 bp | 10 | 260 | 17 | 414 |

| 31-40 bp | 8 | 274 | 5 | 239 |

| 41-50 bp | 1 | 49 | 8 | 346 |

| 51-100 bp | 5 | 353 | 5 | 351 |

| 101-200 bp | 4 | 665 | 2 | 321 |

| 200-400 bp | 1 | 214 | 1 | 231 |

| Small indels | 264 | 2777 | 279 | 2897 |

| All indels | 269 | 19,977 | 286 | 16,009 |

Indels are binned in multiples of 10 bp because of up to an indel length of 50 bp; the last three bins span 50 bp, 100 bp, and 200 bp, respectively, because of the infrequency of these larger indels in either genome. The last two rows tally totals for the number and amount of sequence accounted for by small indels (<400 bp) and all indels, respectively.

One hallmark of illegitimate recombination is the presence of direct flanking repeats 2–15 bp in size (Ma et al. 2004). We searched all indels discovered here for flanking repeats, restricting our attention to the 144-bp indels that were at least 10 bp in length (Ma et al. 2004). Of these, 55 (38%) showed flanking repeats of 2–15 bp (excluding possible mono- or dinucleotide and microsatellite expansion/contraction events). These flanking repeats were unequally distributed in number between the AT and DT genomes (19 vs. 36), but encompassed approximately the same amount of sequence (11,720 and 13,164, respectively). These data suggest that illegitimate recombination is a common mechanism of sequence evolution in Gossypium, and that it may play a role in genome size evolution. Additional analyses that include outgroups for phylogenetic polarization of indels will shed light on the extent and importance of this mechanism.

DISCUSSION

In recent years there has been a rapidly accumulating literature focused on comparative analyses of contiguous, homoeologous stretches of genomic sequence in plants. Stimulated by the seminal investigations of Bennetzen and colleagues on the maize, rice, and sorghum sh2/a1 and Adh regions (SanMiguel et al. 1996; Chen et al. 1997, 1998; Tikhonov et al. 1999) and the increasing accessibility of genomic tools, “microcollinearity” has been studied for numerous other genomic regions and taxa (Ku et al. 2000; Tarchini et al. 2000; Dubcovsky et al. 2001; Rossberg et al. 2001; Wicker et al. 2001; Fu and Dooner 2002; Ramakrishna et al. 2002a; Vandepoele et al. 2002; van Leeuwen et al. 2003; Chantret et al. 2004). Among the generalizations and insights that emerged from these analyses is the concept that gene order and content may be conserved over long periods of evolutionary time (Gale and Devos 1998; Bennetzen 2000a), that polyploidy may lead to a rapid decay in synteny and gene content preservation among homoeologs (Ilic et al. 2003; Kellis et al. 2004; Langham et al. 2004), and that intergenic regions may be subject to more dramatic and rapid evolutionary alterations. The latter in particular has led to the notion that much of the genome size evolution that takes place in plant genomes is caused by differential accumulation of retroelements in intergenic regions (Bennetzen 2000b), although it also is evident from the draft Oryza sativa genome sequence (Goff et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2002) that retroelements may be concentrated near centromeres and other largely heterochromatic regions. Superimposed on these ideas has been the concept that genome size itself may have biological significance and be visible to natural selection (Bennett 1985, 1987; Gregory and Hebert 1999), applying directional pressure on all genomic constituents simultaneously, perhaps through molding genome-specific mutational processes that determine the frequency and spectrum of deletions or insertions (Kirik et al. 2000; Petrov 2002b; Orel and Puchta 2003). Based on the foregoing, we anticipated that the twofold genome size difference that exists between A- and D-genome cotton species might reflect similar phenomena of either differential intergenic retroelement accumulation or perhaps a more globally operating bias in the prevalence and size of insertions and deletions. Neither of these expectations was realized, however, and in addition, a remarkable degree of conservation of the entire CesA1 region was observed, including the size and sequence of most intergenic regions.

Genome Evolution in the CesA1 Region of Polyploid Cotton

The most likely process responsible for the twofold genome size difference between the AT and DT genomes is differential accumulation or retention of transposable elements, particularly retroelements. In the region studied here, however, relatively few TEs were detected, and their differential presence does not correspond with the genome size difference; three of the four unique and intact TE insertions are found in the smaller (DT) of the two genomes, accounting for 15.5 kb in DT versus 5.8 kb in AT. The presence of unique MITEs in AT did little to counteract the disparity, only accounting for +500 bp in AT. Thus, although transposable element amplification may have contributed to the twofold genome size difference, this phenomenon is not evidenced in this genomic region.

The CesA1 region was examined for evidence of ectopic recombination among retroelements. If ectopic recombination has played a role in shaping the CesA1 region, then footprints of the recombined elements should be apparent, such as solo LTRs resulting from recombination between LTRs of individual retroelements or between LTRs of distinct but linked elements (Vicient et al. 1999; Kalendar et al. 2000; Shirasu et al. 2000; Devos et al. 2002; Vitte and Panaud 2003). In the CesA1 region, however, all elements are either fully situated within a span of unique noncoding DNA or are identifiably full length. Thus, although ectopic recombination may play a role in shaping the genome and genome sizes in Gossypium, no evidence of that role was seen here.

Similarly, illegitimate recombination has recently been shown to have the ability to reduce genome size more than was previously anticipated (Ma et al. 2004). The current comparison does not distinguish insertions from deletions, and thus we are unable to accurately gauge the extent to which illegitimate recombination has shaped this region. However, as slightly more than a third of the indels >10 bp in size had flanking repeats, illegitimate recombination may prove to be an active force contributing to genome size evolution in Gossypium. Follow-up studies that distinguish insertions from deletions will further enable an evaluation of the importance of illegitimate recombination in cotton.

Analysis of the sequenced Arabidopsis and rice genomes showed that organelle–nuclear transfers (fragmented or full length) can be common in some genomes (rice) and relatively infrequent in others (Arabidopsis; Shahmuradov et al. 2003). In the present study, one chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) fragment was found in the AT BAC, nestled among unique noncoding DNA. This fragment was only 900 bp in length, however, therefore it does not contribute significantly to genome size evolution in this region.

Despite evidence from broader phylogenetic surveys and some other systems that intron size may be correlated with genome size (Moriyama et al. 1998; Deutsch and Long 1999; Vinogradov 1999; McLysaght et al. 2000), this is not true for genes in the CesA1 region. The average intron size deviation was 4.3 bp per gene (60 bp total). Intron size deviation was not biased with respect to genome; the AT BAC sequence contains a total of only 3 bp more intronic sequence than does its homoeolog. This result is not surprising for Gossypium; a previous study reported for 40 nuclear genes that there exists no significant size variation between Gossypium species groups with varying genome sizes (Senchina et al. 2003). Thus, although intron size expansion/contraction may play a role in shaping the size of other genomes, evidence from Gossypium indicates that it has not played a similar role at the phylogenetic scale encompassed by this genus.

One of the attractive proposals that attempts to account for genome size variation is that there exist biases in the frequency and size of insertions and deletions (Bensasson et al. 2001; Petrov 2002a,b). To evaluate this possibility, we tabulated the spectrum of small indels in the CesA1 region of the AT and DT genomes. The data reveal no evidence of an indel bias (Table 2; Fig. 4). For each indel bin, there were approximately the same number of indels accounting for a similar total of nucleotides. The maximum difference for any bin was 344 bp, which was counteracted through indels in other bins. Overall, the total difference in genome size attributable to small indels is a scant 120 bp (in DT). These observations demonstrate the absence of a globally operating indel bias in Gossypium, despite evidence to the contrary in some other plants (Kirik et al. 2000; Orel and Puchta 2003).

Remarkable Conservation of Intergenic Space

Aside from several TE insertions and a single chloroplast insertion, most intergenic space between the AT and DT genomes is highly conserved. This contrasts with most other studies of microcollinearity, reflecting both the absence of major structural alterations in this genomic region (as discussed above) and perhaps the amount of time that has elapsed since the A and D genomes diverged from their last common ancestor. Yet reports from grasses suggest that ∼11 million years is sufficient to remove homoeology outside of genes (Ramakrishna et al. 2002b; SanMiguel et al. 2002), and, in some cases, only 0.5–1 million years is required (Wicker et al. 2003). Because the AT and DT genomes evolved in isolation on different continents for 5–10 million years prior to becoming reunited by polyploidy ∼1 Mya (Cronn et al. 2002; Senchina et al. 2003), one might not have been surprised by detecting a larger amount of intergenic divergence and lessened sequence identity. The remarkable conservation we observed indicates that the evolutionary forces and molecular mechanisms responsible for rapid intergenic divergence in other plant systems do not operate similarly in this region of Gossypium.

Conclusions

A large body of empirical evidence has demonstrated that myriad external forces and internal molecular genetic mechanisms are involved in the complex suite of phenomena that collectively mold genome size (Petrov 2001; Petrov and Wendel 2004). Recent technological advances in large insert libraries and high-throughput sequencing have made genomic comparisons accessible and feasible, thereby promising increasing application to nonmodel organisms. These comparisons will enable insights into the organization of genomes and their evolution, and are likely to be more informative when conducted within well-understood phylogenetic frameworks. The research described here represents a first step in this direction for Gossypium, which contains, in addition to the A and D genomes, other diploid groups (Fig. 1) whose genome sizes span an even greater range than the twofold size difference studied here. Extension of the present study to include more of this diversity, as well as to additional genomic regions, will enable us to more critically evaluate the suggestion of relative stasis in gene islands and conservation of intergenic sequence reported here. In this regard, the recent publication of a high-density genetic map for Gossypium (Rong et al. 2004) will facilitate targeted selection of genomic regions for analysis.

METHODS

BAC Library Screening and BAC Selection

A cotton (G. hirsutum L.) BAC library (Tomkins et al. 2001) was screened for clones containing a gene encoding cellulose synthase (CesA1), as previously reported (Tomkins et al. 2001). This gene was previously isolated and its sequence determined from A- and D-genome diploid cottons as well as from both genomes of polyploid cotton (Senchina et al. 2003), which facilitated identification of the genomic origin of each BAC. PCR and sequencing were used to verify the presence of CesA1 and to determine which homoeolog of the tetraploid (AT or DT) was represented by each BAC screened. The largest clone from the DT genome (BAC clone 106I22) was sequenced to completion first. Following contig assembly, candidate AT BACs for comparison were evaluated for maximal overlap with the sequenced DT BAC, using a combination of PCR screening of inferred genes (3 and 11; see Fig. 2) as well as BAC-end sequencing. Because the G. hirsutum BAC library was created using partially digested (HindIII) genomic DNA, some BAC ends were conserved and shared among homoeologs. Thus, an AT clone that shared a BAC end sequence and tested genes with 106I22 (AT BAC clone 155C17) was verified as providing maximum overlap for the region. This clone was then sequenced as described below.

Shotgun Sequencing, Assembly, and Analysis

BAC DNA was sheared using a HydroShear (GeneMachines) DNA shearing device at speed code 12 with 25 cycles at room temperature. Fragmented DNA was end-repaired using the “End-it” DNA end repair kit (Epicentre), separated on an agarose gel, and size-selected for a range of 2–6 kb. This prepared insert DNA was randomly cloned into a pBluescript II KS+ vector (Strategene) and sequenced with the universal vector primers T7 and T3 to an average depth of 8× (∼1152 clones in AT and 1920 clones in DT). The resulting sequences were base-called using the program Phred (Ewing and Green 1998; Ewing et al. 1998), vector sequences were removed by CROSS_MATCH (Ewing and Green 1998; Ewing et al. 1998), and assembled by the program Phrap (Green 1999). Contigs were visualized and edited with CONSED (Gordon et al. 1998). Potential genes were predicted by three independent programs: FGENESH (http://www.softberry.com/), GeneMark.hmm (Lukashin and Borodovsky 1998), and GENSCAN+ (Burge and Karlin 1997). Predicted proteins were used as input for BLASTP searches against the nonredundant GenBank protein database. To further investigate potential genes in the assembled sequence, 500-bp segments of each assembled BAC were subjected to BLASTX queries against the nonredundant GenBank protein database and BLASTN queries against the cotton EST database.

Alignment of the homoeologous BACs to each other was accomplished using LAGAN (Brudno et al. 2003). The resulting alignment was checked manually for errors using BIOEDIT (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html).

Preliminary mining for repetitive elements was accomplished through RepeatMasker (http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/RM/RepeatMasker.html), CENSOR (Jurka et al. 1996), and BLAST homoeology to known elements in RepBase (version 8.5; Jurka 2000). MITEs were mined using the program FINDMITE (Tu 2001) and querying the results for repetitiveness in the genome (J.S. Hawkins, H-R. Kim, R.A. Wing, J.D. Nason, and J.F. Wendel, unpubl.), as well as by searching for conserved Arabidopsis TIR and TSD sequences. Each potential MITE was inspected manually to ensure that the predicted TIRs were not composed primarily of simple sequence repeats that would generate a false prediction. In addition, each BAC was queried against itself in 500-bp fragments to reveal potentially missed repetitive elements. Finally, each BAC was again queried in 500-bp fragments against whole-genomic shotgun sequences characterized by an ongoing study (J.S. Hawkins, H-R. Kim, R.A. Wing, J.D. Nason, and J.F. Wendel, unpubl.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Trent Grover, Jamie Estill, and Jordan Swanson for technical assistance; Anna Gardner for help with Figure 3; Jennifer Hawkins for helpful discussion and assistance with some analyses; and Cedric Feschotte for guidance concerning mining for MITEs. This work was funded by the National Science Foundation Plant Genome program, whose support we gratefully acknowledge.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.2673204. Article published online ahead of print in July 2004.

Footnotes

References

- Adams, K.L. and Palmer, J.D. 2003. Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: Gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29: 380–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. 2000. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408: 796–815.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.D. 1985. Intraspecific variation in DNA amount and the nucleotypic dimension in plant genetics. In Plant genetics (ed. M. Freeling), pp. 283–302. A.R. Liss, New York.

- Bennett, M.D. 1987. Variation in genomic form and its ecological implications. New Phytol. 106: 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.D. and Leitch, I.J. 1995. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Annals Bot. 76: 113–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.D. and Leitch, I.J. 1997. Nuclear DNA amount in angiosperms. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London B 334: 309–345. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.D. and Leitch, I.J. 2003. Plant DNA C-values database. http://www.rbgkew.org.uk/cval/homepage.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bennetzen, J.L. 2000a. Comparative sequence analysis of plant nuclear genomes: Microcolinearity and its many exceptions. Plant Cell 12: 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J.L. 2000b. Transposable element contributions to plant gene and genome evolution. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 251–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J.L. 2002. Mechanisms and rates of genome expansion and contraction in flowering plants. Genetica 115: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J.L. and Kellogg, E.A. 1997. Do plants have a one-way ticket to genomic obesity? Plant Cell 9: 1509–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensasson, D., Petrov, D.A., Zhang, D.X., Hartl, D.L., and Hewitt, G.M. 2001. Genomic gigantism: DNA loss is slow in mountain grasshoppers. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran, E. and Long, M. 2002. Expansion of genome coding region by acquisition of new genes. Genetica 115: 65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biderre, C., Metenier, G., and Vivares, C.P. 1998. A small spliceosomal-type intron occurs in a ribosomal protein gene of the microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 74: 229–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudno, M., Do, C., Cooper, G., Kim, M.F., Davydov, E., Green, E.D., Sidow, A., and Batzoglou, S. 2003. LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: Efficient tools for large scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 13: 721–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge, C. and Karlin, S. 1997. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 268: 78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith, T. 1985. The evolution of genome size. John Wiley, New York.

- Chantret, N., Cenci, A., Sabot, F., Anderson, O., and Dubcovsky, J. 2004. Sequencing of the Triticum monococcum Hardness locus reveals good microcolinearity with rice. Mol. Genet. Genom. Online First: 1617–4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M., SanMiguel, P., de Oliveira, A.C., Woo, S.-S., Zhang, H., Wing, R.A., and Bennetzen, J.L. 1997. Microcolinearity in sh2-homoeologous regions of the maize, rice, and sorghum genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 3431–3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.S., SanMiguel, P., and Bennetzen, J.L. 1998. Sequence organization and conservation in sh2/a1-homoeologous regions of sorghum and rice. Genetics 148: 435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chooi, W.Y. 1971. Variation in nuclear DNA content in the genus Vicia. Genetics 68: 195–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie, J.-M. 2000. What if there are only 30,000 human genes? Science 291: 1255–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronn, R.C., Small, R.L., Haselkorn, T., and Wendel, J.F. 2002. Rapid diversification of the cotton genus (Gossypium: Malvaceae) revealed by analysis of sixteen nuclear and chloroplast genes. Am. J. Botany 89: 707–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M. and Long, M. 1999. Intron–exon structure of eukaryotic model organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 3219–3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos, K.M., Brown, J.K.M., and Bennetzen, J.L. 2002. Genome size reduction through illegitimate recombination counteracts genome expansion in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 12: 1075–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubcovsky, J., Ramakrishna, W., SanMiguel, P.J., Busso, C.S., Yan, L.L., Shiloff, B.A., and Bennetzen, J.L. 2001. Comparative sequence analysis of colinear barley and rice bacterial artificial chromosomes. Plant Physiology 125: 1342–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endrizzi, J.D., Turcotte, E.L., and Kohel, R.J. 1985. Genetics, cytology, and evolution of Gossypium. Adv. Genet. 23: 271–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B. and Green, P. 1998. Basecalling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8: 186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B., Hillier, L., Wendl, M.C., and Green, P. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequences traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8: 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C. and Mouches, C. 2000. Evidence that a family of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome has arisen from a POGO-like DNA transposon. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17: 730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., Zhang, X., and Wessler, S.R. 2002. Miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements and their relationship to established DNA transposons. In Mobile DNA II (ed. N.L. Craig). ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Fu, H.H. and Dooner, H.K. 2002. Intraspecific violation of genetic colinearity and its implications in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 9573–9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale, M.D. and Devos, K.M. 1998. Plant comparative genetics after 10 years. Science 282: 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff, S.A., Ricke, D., Lan, T.H., Presting, G., Wang, R., Dunn, M., Glazebrook, J., Sessions, A., Oeller, P., Varma, H., et al. 2002. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 296: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, D., Abajian, C., and Green, P. 1998. CONSED: A graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, P. 1999. Phrap documentation. http://www.phrap.org/phrap.docs/phrap.html.

- Gregory, T.R. 2001. Animal genome size database. http://www.genomesize.com.

- Gregory, T.R. 2002. Genome size and developmental complexity. Genetica 115: 131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, T.R. and Hebert, P.D.N. 1999. The modulation of DNA content: Proximate causes and ultimate consequences. Genome Res. 9: 317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, K., SanMiguel, P.J., and Bennetzen, J.L. 2003. A complex history of rearrangement in an orthologous region of the maize, sorghum, and rice genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 12265–12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.N. and Brown, L.M. 1976. Chromosome evolution and DNA variation in Crepsis. Heredity 36: 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J. 2000. Repbase Update: A database and an electronic journal of repetitive elements. Trends Genet. 9: 418–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J., Klonowski, P., Dagman, V., and Pelton, P. 1996. CENSOR—A program for identification and elimination of repetitive elements from DNA sequences. Comput. Chem. 20: 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalendar, R., Tanskanen, J., Immonen, S., Nevo, E., and Schulman, A.H. 2000. Genome evolution in wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) by BARE-1 retrotransposon dynamics in response to sharp microclimatic divergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 6603–6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis, M., Birren, B.W., and Lander, E. 2004. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 428: 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik, A., Salomon, S., and Puchta, H. 2000. Species-specific double-strand break repair and genome evolution in plants. EMBO J. 2000: 5562–5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku, H.M., Vision, T., Liu, J., and Tanksley, S.D. 2000. Comparing sequenced segments of tomato and Arabidopsis genomes: Large scale duplication followed by selective gene loss creates a network of synteny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 9121–9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langham, R.J., Walsh, J., Dunn, M., Ko, C., Goff, S.A., and Freeling, M. 2004. Genomic duplication, fractionation and the origin of regulatory novelty. Genetics 166: 935–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley, C.H., Montgomery, E., Hudson, R., Kaplan, N., and Charlesworth, B. 1988. On the role of unequal exchange in the containment of transposable element copy number. Genet. Res. 52: 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch, I.J., Chase, M.W., and Bennett, M.D. 1998. Phylogenetic analysis of DNA C-values provides evidence for a small ancestral genome size in flowering plants. Annals Bot. (Suppl. A) 82: 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.-H. 1997. Molecular evolution. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Li, W.-H. and Graur, D. 1991. Fundamentals of molecular evolution. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Lukashin, A. and Borodovsky, M. 1998. GeneMark.hmm: New solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 1107–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., Devos, K.M., and Bennetzen, J.L. 2004. Analyses of LTR-retrotransposon structures reveal recent and rapid genomic DNA loss in rice. Genome Res. 14: 860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLysaght, A., Enright, A.J., Skrabanek, L., and Wolfe, K.H. 2000. Estimation of synteny conservation and genome compaction between pufferfish (Fugu) and human. Yeast 17: 22–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky, A.E. and Ris, H. 1951. The DNA content of animal cells and its evolutionary significance. J. Gen. Physiol. 34: 451–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama, E.N., Petrov, D.A., and Hartl, D.L. 1998. Genome size and intron size in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15: 770–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orel, N. and Puchta, H. 2003. Differences in the processing of DNA ends in Arabidopsis thaliana and tobacco: Possible implications for genome evolution. Plant Mol. Biol. 51: 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, D.A. 2001. Evolution of genome size: New approaches to an old problem. Trends Genet. 17: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, D.A. 2002a. DNA loss and evolution of genome size in Drosophila. Genetica 115: 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, D.A. 2002b. Mutational equilibrium model of genome size evolution. Theoret. Pop. Biol. 61: 531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, D.A. and Wendel, J.F. 2004. Evolution of eukaryotic genome structure. In Evolutionary genetics: Concepts and case studies (eds. C.W. Fox and J.B. Wolf). Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford.

- Petrov, D.A., Aminetzach, Y.T., Davis, J.C., Bensasson, D., and Hirsh, A.E. 2003. Size matters: Non-LTR retrotransposable elements and ectopic recombination in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 880–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, W., Dubcovsky, J., Park, Y.J., Busso, C., Emberton, J., SanMiguel, P., and Bennetzen, J.L. 2002a. Different types and rates of genome evolution detected by comparative sequence analysis of orthologous segments from four cereal genomes. Genetics 162: 1389–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, W., Emberton, J., Ogden, M., SanMiguel, P., and Bennetzen, J.L. 2002b. Structural analysis of the maize Rp1 complex reveals numerous sites and unexpected mechanisms of local rearrangement. Plant Cell 14: 3213–3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium. 2003. In-depth view of structure, activity, and evolution of rice chromosome 10. Science 300: 1566–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong, J., Abbey, C., Bowers, J.E., Brubaker, C.L., Chang, C., Chee, P.W., Delmonte, T.A., Ding, X., Garza, J.J., and Marler, B.S., 2004. A 3347-locus genetic recombination map of sequence-tagged sites reveals features of genome organization, transmission and evolution of cotton (Gossypium). Genetics 166: 389–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossberg, M., Theres, K., Acarkan, A., Herrero, R., Schmitt, T., Schumacher, K., Schmitz, G., and Schmidt, R. 2001. Comparative sequence analysis reveals extensive microcolinearity in the Lateral suppressor regions of the tomato, Arabidopsis, and Capsella genomes. Plant Cell 13: 979–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel, P., Tikhonov, A., Jin, Y.K., Motchoulskaia, N., Zakharov, D., Melake-Berhan, A., Springer, P.S., Edwards, K.J., Lee, M., Avramova, Z., et al. 1996. Nested retrotransposons in the intergenic regions of the maize genome. Science 274: 765–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel, P., Gaut, B.S., Tikhonov, A., Nakajima, Y., and Bennetzen, J.L. 1998. The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nat. Genet. 20: 43–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel, P., Ramakrishna, W., Bennetzen, J.L., Busso, C.S., and Dubcovsky, J. 2002. Transposable elements, genes, and recombination in a 215 kb contig from wheat chromosome 5Am. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2: 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelanan, T., Schnabel, A., and Wendel, J.F. 1997. Congruence and consensus in the cotton tribe. Syst. Bot. 22: 259–290. [Google Scholar]

- Senchina, D.S., Alvarez, I., Cronn, R.C., Liu, B., Rong, J.K., Noyes, R.D., Paterson, A.H., Wing, R.A., Wilkins, T.A., and Wendel, J.F. 2003. Rate variation among nuclear genes and the age of polyploidy in Gossypium. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahmuradov, I.A., Akbarova, Y.Y., Solovyev, V.V., and Aliyev, J.A. 2003. Abundance of plastid DNA insertions in nuclear genomes of rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 52: 923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu, K., Schulman, A.H., Lahaye, T., and Schulze-Lefert, P. 2000. A contiguous 66-kb barley DNA sequence provides evidence for reversible genome expansion. Genome Res. 10: 908–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small, R.L., Ryburn, J.A., Cronn, R.C., Seelanan, T., and Wendel, J.F. 1998. The tortoise and the hare: Choosing between noncoding plastome and nuclear ADH sequences for phylogeny reconstruction in a recently diverged plant group. Am. J. Botany 85: 1301–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarchini, R., Biddle, P., Wineland, R., Tingey, S., and Rafalski, A. 2000. The complete sequence of 340 kb of DNA around the rice Adh1–Adh2 region reveals interrupted colinearity with maize chromosome 4. Plant Cell 12: 381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.A. 1971. The genetic organisation of chromosomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 5: 237–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, A.P., SanMiguel, P.J., Nakajima, Y., Gorenstein, N.M., Bennetzen, J.L., and Avramova, Z. 1999. Colinearity and its exceptions in orthologous adh regions of maize and sorghum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 7409–7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, J.P., Peterson, D.G., Yang, T.J., Main, D., Wilkins, T.A., Paterson, A.H., and Wing, R.A. 2001. Development of genomic resources for cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.): BAC library construction, preliminary STC analysis, and identification of clones associated with fiber development. Mol. Breed. 8: 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z. 2001. Eight novel families of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements in the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 1699–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele, K., Saeys, Y., Simillion, C., Raes, J., and Van de Peer, Y. 2002. The automatic detection of homoeologous regions (ADHoRe) and its application to microcolinearity between Arabidopsis and rice. Genome Res. 12: 1792–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, H., Monfort, A., Zhang, H.B., and Puigdomenech, P. 2003. Identification and characterisation of a melon genomic region containing a resistance gene cluster from a constructed BAC library. Microcolinearity between Cucumis melo and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 51: 703–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicient, C.M., Suoniemi, A., Anamthawat-Jonsson, K., Tanskanen, J., Beharav, A., Nevo, E., and Schulman, A.H. 1999. Retrotransposon BARE-1 and its role in genome evolution in the genus Hordeum. Plant Cell 11: 1769–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov, A.E. 1999. Intron–genome size relationship on a large evolutionary scale. J. Mol. Evol. 49: 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vision, T.J., Brown, D.G., and Tanksley, S.D. 2000. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 290: 2114–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitte, C. and Panaud, O. 2003. Formation of solo-LTRs through unequal homoeologous recombination counterbalances amplifications of LTR retrotransposons in rice Oryza sativa L. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 528–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel, J.F. 2000. Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 225–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel, J.F. and Cronn, R.C. 2003. Polyploidy and the evolutionary history of cotton. Adv. Agron. 78: 139–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel, J.F., Cronn, R.C., Alvarez, I., Liu, B., Small, R.L., and Senchina, D.S. 2002a. Intron size and genome size in plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 2346–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel, J.F., Cronn, R.C., Johnston, J.S., and Price, H.J. 2002b. Feast and famine in plant genomes. Genetica 115: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker, T., Stein, N., Albar, L., Feuillet, C., Schlagenhauf, E., and Keller, B. 2001. Analysis of a continuous 211 kb sequence in diploid wheat (Triticum monococcum L.) reveals multiple mechanisms of genome evolution. Plant J. 26: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker, T., Yahiaoui, N., Guyot, R., Schlagenhauf, E., Liu, Z.-D., Dubcovsky, J., and Keller, B. 2003. Rapid genome divergence at orthologous low molecular weight glutenin loci of the A and Am genomes of wheat. Plant Cell 15: 1186–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., Hu, S., Wang, J., Wong, G.K., Li, S., Liu, B., Deng, Y., Dai, L., Zhou, Y., Zhang, X., et al. 2002. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 296: 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. 2003. Evolution by gene duplication: An update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18: 292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.P., Si, Y., Hanson, R.E., Crane, C.F., Price, H.J., Stelly, D.M., Wendel, J.F., and Paterson, A.H. 1998. Dispersed repetitive DNA has spread to new genomes since polyploid formation in cotton. Genome Res. 8: 479–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/RM/RepeatMasker.html; RepeatMasker.

- http://lagan.stanford.edu/; LAGAN alignment toolkit.

- http://www.genomesize.com; Animal genome size database.

- http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html; Biological sequence alignment editor.

- http://www.phrap.org/; Phred/Phrap/Consed.

- http://www.softberry.com/; Softberry.

- http://www.rbgkew.org.uk/cval/homepage.html; Plant C-value database.