Abstract

Purpose

Accurate risk assessment is necessary for decision-making around breast cancer prevention. We aimed to develop a breast cancer prediction model for postmenopausal women that would take into account their individualized competing risk of non-breast cancer death.

Methods

We included 73,066 women who completed the 2004 Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) questionnaire (all ≥57 years) and followed participants until May 2014. We considered 17 breast cancer risk factors (health behaviors, demographics, family history, reproductive factors), 7 risk factors for non-breast cancer death (comorbidities, functional dependency), and mammography use. We used competing risk regression to identify factors independently associated with breast cancer. We validated the final model by examining calibration (expected-to-observed ratio of breast cancer incidence, E/O) and discrimination (c-statistic) using 74,887 subjects from the Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study (WHI-ES; all were ≥55 years and followed for 5 years).

Results

Within 5 years, 1.8% of NHS participants were diagnosed with breast cancer (vs. 2.0% in WHI-ES, p=0.02) and 6.6% experienced non-breast cancer death (vs. 5.2% in WHI-ES, p<0.001). Using a model selection procedure which incorporated the Akaike Information Criterion, c-statistic, statistical significance, and clinical judgement, our final model included 9 breast cancer risk factors, 5 comorbidities, functional dependency, and mammography use. The model’s c-statistic was 0.61 (95% CI [0.60–0.63]) in NHS and 0.57 (0.55–0.58) in WHI-ES. On average our model under predicted breast cancer in WHI-ES (E/O 0.92 [0.88–0.97]).

Conclusions

We developed a novel prediction model that factors in postmenopausal women’s individualized competing risks of non-breast cancer death when estimating breast cancer risk.

Keywords: breast cancer prediction, competing risks, older

INTRODUCTION

Accurate breast cancer risk assessment is necessary to make informed decisions about breast cancer screening and prevention.[1, 2] However, no available breast cancer prediction model considers a woman’s individualized risk of non-breast cancer death. Several models (e.g. Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool [BCRAT], Tyrer-Cuzick [IBIS], and Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium [BCSC]), factor in a woman’s risk of non-breast cancer death based on age alone.[3–5] As life expectancy varies based on comorbidities and functional status,[6] not accounting for individualized competing risks of non-breast cancer death risk may lead to inaccurate breast cancer risk estimation among older women.

Statistical methods, such as Fine and Gray’s competing risk regression, take into account an individual’s risk of non-breast cancer death when estimating breast cancer risk.[7] Conventional methods, such as cause-specific hazard models using Cox proportional hazards regression, focus on the outcome of interest (e.g., breast cancer) and censor women that die from a competing risk before follow-up ends.[8] When death is a common competing event, as it is for elderly women, proportional hazards regression models overestimate risk factor influence on breast cancer incidence since they do not adjust for the reduction in the at risk population due to alternative causes of death.[8–10] In competing risk regression, women with death from a competing cause are considered no longer at risk for breast cancer. Instead, these women are assigned a weight that is used in the partial likelihood function for breast cancer to account for the time during follow-up that these women were alive before their non-breast cancer death.[11] Experts recommend using competing risk regression for predictive modeling in populations with a high frequency of competing events.[12]

Therefore, we aimed to develop a breast cancer prediction model for postmenopausal women using competing risk regression that would 1) take into account their individualized competing risk of non-breast cancer death, 2) include factors important for estimating postmenopausal breast cancer risk, and 3) use self-reported information for ease of clinical use.

METHODS

Data

We developed our prediction model using Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) data, a longitudinal study of 121,700 female nurses, 30–55 years of age at entry.[13] At baseline and in biennial follow-ups, NHS participants provide detailed lifestyle and medical history information through mailed questionnaires. Our study sample included all NHS participants that returned the 2004 questionnaire. Since this questionnaire could be returned through May 2006, time of entry into our study varied. We excluded women (n=9,388) with a history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) since second diagnoses of cancer are not confirmed. Participants were 57–85 years and postmenopausal at study entry.

Outcomes

We followed participants until they developed invasive breast cancer, died, or May 2014, whichever came first. We included breast cancers confirmed by medical record review and self-reported breast cancers (12% of cases) since validation studies found that self-reported breast cancers in NHS are accurate (99% confirmed with medical record review).[14]

Possible Risk Factors

We considered four classes of variables in NHS that have been associated with breast cancer in our model, including: demographics (age [in 5 year categories for ease of clinical use], race/ethnicity), family history, reproductive factors, and health behaviors.[1] We also considered history of non-traumatic post-menopausal fracture since such fractures may be suggestive of lower estrogen levels.[15] For family history we considered history of first degree female relatives with breast cancer and their age at diagnosis (<50 vs ≥50), history of breast cancer in a grandmother, family history of ovarian cancer, and Ashkenazi Jewish decent. For reproductive factors, we considered age at menarche, menopause, and at first live birth, parity, months breastfeeding, and history of bilateral oophorectomy. Age at menopause for women who underwent simple hysterectomy was derived using a life table approach that incorporated age at surgery, exogenous hormone use, and smoking status. For health behaviors we considered physical activity, body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, cigarette use, postmenopausal hormone therapy use and duration of use (<5, 5+ years) for past users, and benign breast biopsy history. While some have found that hormone therapy use modifies the effect of obesity on breast cancer risk, these findings are not consistent, and there were too few current users to consider this interaction.[16, 17] Since weight, alcohol consumption, and physical activity tend to decline with advanced age, we used maximum BMI and maximum average alcohol consumption per day and average physical activity per week reported in the past 10 years. We also considered the influence of mammography use in the past 2 years which increases detection and estimated risk among screened women and may confound the influence of some risk factors (e.g., family history, breast biopsy history) on breast cancer incidence since these risk factors are associated with increased mammography use.[18]

Factors associated with non-breast cancer death

Competing risk regression assigns a weight to non-breast cancer deaths that is used in the partial likelihood function for assessing breast cancer risk.[7] The assigned weight takes into account the amount of time a participant was in the risk set before experiencing non-breast cancer death and is a function of factors that are related to both breast cancer incidence and non-breast cancer death (see formula in Appendix). Therefore, we considered additional factors in our model known to be associated with death.[6] Specifically, we considered Charlson comorbidities that were prevalent in >1% of our cohort and that may be self-reported accurately including: diabetes, myocardial infarction (MI), emphysema, congestive heart failure, and stroke.[19, 20] We also considered being limited in moderate daily activities, in bathing oneself, and in walking several blocks (mobility).[21, 22]

External Validation

We examined our model’s performance among WHI extension study participants (WHI-ES). We chose to examine our model’s performance in a different cohort from the one in which it was developed because we wanted to examine our model’s generalizability (external validity). WHI was a multicenter study that recruited 161,808 postmenopausal US women ages 50–79 in up to four clinical trials (WHI-CTs) or an observational study (WHI-OS) from 1993–1998 and followed women through March 2005. In 2005, 82% of WHI-CT participants and 73% of WHI-OS participants agreed to an observation-only extension study (n=115,396) through March 2010.15 In 2010, 86.7% (n=79,572) of the 91,800 participants alive agreed to a second extension study through March 2015. We examined our model’s performance among WHI-ES participants since the time period matched our NHS cohort and WHI collected the necessary information. WHI-ES participants were 55–91 years at study entry (89 women were 55–56). We followed WHI-ES participants until they developed invasive breast cancer (all cases confirmed by pathology report), died, the end of WHI-ES1 or the end of WHI-ES2 in 2015 for women that participated in WHI-ES2. To be consistent with NHS we excluded participants (n=9,778) with history of cancer, except for non-melanoma skin cancers. We also excluded participants missing data on our final model’s risk factors (n=22,229).

Detailed descriptions of each cohort and risk factor and outcome variable definitions are in the Appendix.

Statistical Analyses

Model development

We used competing risk regression (CRR) and included all possible breast cancer risk factors. To avoid collinearity, we did not include variables correlated at ≥0.3 using the Spearman correlation. Women missing risk factor information were included in the model using an indicator variable for missing. We first examined the individual contribution of each breast cancer risk factor on the model’s Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and c-statistic in predicting breast cancer.[23] We kept breast cancer risk factors in the model that improved the AIC and c-statistic, and were statistically significant at p<0.05.

In sensitivity analyses, we examined our model’s performance stratified by age (55–74 vs. 75+ years) and we re-ran our model excluding women missing risk factor information. We also re-ran our analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression (PHR).

External Validation

We used chi-square statistics to compare the prevalence of risk factors in each cohort. We then examined model calibration (whether our model’s predicted probabilities are accurate) and discrimination (how well our model distinguishes between individuals who do or do not develop breast cancer).[24] To assess calibration, we compared the expected (E) number of breast cancers at 5 years based on our model’s estimates to the observed number (O) in WHI-ES. We examined calibration at 5 years, since we do not have information on whether 8,702 WHI-ES participants developed breast cancer after 5 years since they did not consent to WHI-ES2. To determine the expected number of breast cancers among WHI-ES participants at five years, we first obtained the baseline 5-year cumulative incidence function for breast cancer from our NHS model. This allowed us to estimate the baseline breast cancer risk for WHI-ES women without any risk factors. [11] We then multiplied this baseline risk by a WHI-ES woman’s individualized hazard ratio for developing breast cancer (calculated based on the presence or absence of risk factors) to estimate breast cancer risk for each WHI-ES participant. Next, we summed these breast cancer risk estimates to obtain the total number of WHI-ES women expected to have breast cancer in 5 years. We repeated these analyses for each risk decile and age group (55–74, 75+). We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of E/O ratios using the Poisson variance for the logarithm of the observed number of cases.[25]

To assess discrimination, we used the 5-year breast cancer risk estimates for each WHI-ES participant (calculated as described above) and the observed survival times for WHI-ES participants to compute the c-index (equivalent to c-statistic in logistic regression) and its standard error.[26–28] This area ranges from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination). In sensitivity analyses, we examined our model’s performance by age (55–74, 75+ years) and limited WHI-ES to non-Hispanic whites.

To examine if there were differences in the effect of breast cancer risk factors on developing breast cancer between NHS and WHI-ES, we re-ran our model using CRR in WHI-ES. We then compared the effect of each risk factor on developing breast cancer between cohorts using the normal approximation z-test by dividing each risk factor’s beta (parameter estimate) by its standard error.

Finally, we demonstrated the practicality of our model by presenting 5-year breast cancer risk predictions for women with different breast cancer risk factors and health characteristics. We also present BCRAT and BCSC risk estimates for these women. All analyses were completed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., NC).

RESULTS

Model Development and Validation Samples

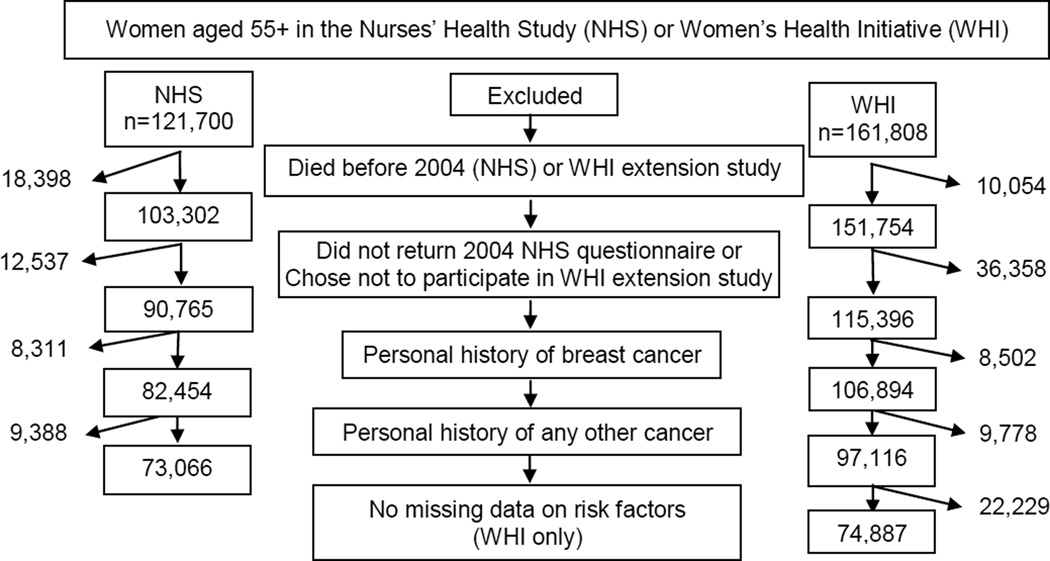

We included 73,066 NHS participants and examined model performance among 74,887 WHI-ES participants (Figure 1). Compared with WHI-ES participants, NHS participants were more likely to be non-Hispanic white, nulliparous, to have significant illness, family history of breast cancer, and to have used hormone therapy, but were less likely to have a BMI ≥30 (kg/m2) or to have been <45 years at menopause (Table 1). Within 5 years, 1.8% of NHS participants were diagnosed with breast cancer compared to 2.0% of WHI-ES participants (p=0.02) and 6.6% of NHS participants experienced non-breast cancer death compared to 5.2% of WHI-ES participants (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Model development and validation samples.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, overall and by age, among Nurses’ Health Study (n=73,066) and Women’s Health Initiative-Extension Study (n=74,887) participants.a, b

| NHSa | WHI-ESa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 57–74c years |

75+ years |

Overall | 55–74 years |

75+ years |

|

| N | 73,066 | 53,362 | 19,704 | 74,887 | 53,829 | 21,058 |

| Breast cancer risk factors in our final model | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 70 (7.0) |

66 (4.8) |

79 (2.4) |

71 (6.7) |

67 (4.5) |

79 (3.1) |

| 55–59 years, % | 7.4 | 10.1 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 0.0 |

| 60–64 years, % | 22.3 | 30.6 | 0.0 | 19.3 | 26.8 | 0.0 |

| 65–69 years, % | 22.7 | 31.1 | 0.0 | 25.3 | 35.2 | 0.0 |

| 70–74 years, % | 20.7 | 28.3 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 32.2 | 0.0 |

| 75–79 years, % | 17.6 | 0.0 | 65.2 | 18.1 | 0.0 | 64.5 |

| 80+ years, % | 9.4 | 0.0 | 34.8 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 35.5 |

|

Number of first-degree relatives with history of breast cancer and age at diagnosis |

||||||

| None, % | 82.3 | 83.3 | 79.6 | 86.5 | 87.2 | 84.8 |

| 1 and age <50 % (<45 in WHI) | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| 1 and age 50+ (45+ in WHI) or unknown age, % | 11.5 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 11.0 |

| 2+ and at least one age <50 (<45 in WHI), % | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| 2+ and age 50+ (45+ in WHI)/unknown, % | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| Number of breast biopsies | ||||||

| 0, % | 73.6 | 72.6 | 76.2 | 71.6 | 71.6 | 71.8 |

| 1, % | 23.2 | 23.8 | 21.5 | 17.7 | 17.7 | 17.7 |

| 2+, % | 3.3 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.5 |

| Postmenopausal hormone use | ||||||

| Never, % | 22.6 | 22.1 | 24.1 | 29.1 | 25.6 | 38.0 |

| Current estrogen plus progestin user, % | 3.3 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.0 |

| Current estrogen-alone user, % | 10.1 | 11.2 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 5.8 |

| Past estrogen plus progestin user <5 years, % | 15.2 | 16.9 | 10.3 | 13.7 | 14.4 | 11.8 |

| Past estrogen plus progestin user 5+ years, % | 16.4 | 19.3 | 8.6 | 22.2 | 25.3 | 14.3 |

| Past estrogen-alone user <5 years, % | 6.9 | 5.6 | 10.5 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 8.6 |

| Past estrogen-alone user 5+ years, % | 13.5 | 12.5 | 16.2 | 20.0 | 19.8 | 20.5 |

| Unknown, % | 12.0 | 8.3 | 22.0 | - | - | - |

|

Highest Body Mass Index (BMI) in past 10 yearsd |

||||||

| <20 kg/m2, % | 2.7 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| 20–24 kg/m2, % | 30.4 | 28.8 | 34.5 | 22.8 | 22.0 | 24.8 |

| 25–29 kg/m2, % | 36.5 | 36.0 | 38.0 | 36.0 | 34.6 | 39.4 |

| 30+ kg/m2, % | 30.3 | 32.9 | 23.3 | 40.1 | 42.2 | 34.6 |

| Unknown, % | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | - | - | - |

| Age at menopause (years) | ||||||

| <45, % | 10.3 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 20.6 | 20.4 | 21.0 |

| 45–49, % | 23.7 | 23.5 | 24.0 | 26.4 | 27.3 | 24.1 |

| 50–54, % | 56.2 | 55.0 | 59.5 | 39.3 | 40.8 | 35.4 |

| 55+, % | 8.8 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 13.7 | 11.5 | 19.5 |

| Unknown, % | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 | - | - | - |

|

Average alcohol use per day (highest average use in past 10 years)e |

||||||

| None, % | 36.8 | 33.3 | 46.1 | 39.2 | 38.0 | 42.2 |

| 1–4.9 gram/day, % | 22.7 | 24.7 | 17.4 | 24.5 | 25.3 | 22.3 |

| 5–14.9 gram/day, % | 17.4 | 18.0 | 15.6 | 20.0 | 20.4 | 19.0 |

| 15+ gram/day, % | 13.3 | 13.7 | 12.1 | 16.4 | 16.4 | 16.5 |

| Unknown, % | 9.9 | 10.3 | 8.8 | - | - | - |

| Age at first birth (years) and parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| <25, 1–2 children/ unknown number | 14.2 | 16.3 | 8.6 | 18.7 | 20.6 | 14.0 |

| <25, 3+ children | 35.5 | 37.8 | 29.3 | 42.6 | 44.2 | 38.6 |

| 25–29, 1–2 children/unknown number | 14.9 | 15.8 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 11.3 |

| 25–29, 3+ children | 20.0 | 17.0 | 28.4 | 13.9 | 11.0 | 21.3 |

| 30+, 1–2 children/unknown number | 5.7 | 4.9 | 7.9 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 7.2 |

| 30+, 3+ children | 2.8 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 4.6 |

| Unknown | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | - | - | - |

| Cigarette use | ||||||

| Never | 45.1 | 44.1 | 48.0 | 51.1 | 49.5 | 55.1 |

| Current | 7.9 | 8.9 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 2.4 |

| Past | 46.8 | 46.9 | 46.6 | 44.9 | 45.8 | 42.5 |

| Unknown | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | - | - | - |

| Mammogram in past 2 yearsf | ||||||

| No | 10.9 | 9.0 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 12.9 | 18.9 |

| Yes | 80.8 | 82.5 | 75.9 | 85.4 | 87.1 | 81.1 |

| Unknown | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.3 | - | - | - |

| Health Conditions in our final modelg | ||||||

| Diabetes | 11.1 | 10.4 | 13.0 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 10.0 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 2.6 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 5.9 |

| Stroke | 2.2 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Emphysema | 7.7 | 6.5 | 10.9 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 7.4 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.1 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 3.9 |

| Limited in moderate daily activity | ||||||

| Not at all limited | 59.3 | 65.9 | 41.5 | 64.1 | 70.6 | 47.5 |

| Limited | 35.3 | 28.6 | 53.7 | 35.9 | 29.4 | 52.5 |

| Missing | 5.4 | 5.6 | 4.8 | - | - | - |

| Outcomesh | ||||||

| Breast cancer in first five years, % | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Non-breast cancer death in first five years, % | 6.6 | 3.5 | 15.1 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 10.8 |

| Breast cancer up to 10 year follow-up, % | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.0 |

|

Non-breast cancer death up to 10 year follow up, % |

13.6 | 7.4 | 30.6 | 10.2 | 6.0 | 20.9 |

|

Factors considered but were not included in our final modeli |

||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White,% | 96.2 | 96.1 | 96.3 | 87.0 | 85.6 | 90.6 |

| Non-Hispanic Black,% | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 4.6 |

| Hispanic,% | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.4 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander % | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| Native American,% | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Unknown,% | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

NHS=Nurses’ Health Study included participants that completed the 2004 questionnaire; WHI-ES=Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study which began in 2005- the sample excluded women missing data on variables in our final model.

All comparisons between NHS and WHI-ES overall were statistically significant at p<0.001 using chi-square statistics except for stroke.

The youngest women in NHS at study entry were 57 years.

Body mass index was based on nurse self-report in NHS and was measured in WHI.

A standard drink is any drink that contains about 14 grams of pure alcohol (12 oz. of beer, 5 oz. of wine or 1.5 oz. of liquor)[48]

Women missing data on mammography use in NHS had completed a short version of the 2004 questionnaire.

In NHS, diabetes, myocardial infarction, and stroke were confirmed by participants and/or adjudicated by review of their medical records. Congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke were physician-adjudicated with medical records in WHI-ES.

NHS participants were followed through May 2014. All WHI participants were followed through March 2010; 58,534 WHI participants were followed through March 2015.

Other variables that were considered in our NHS model (e.g., age at menarche, months breastfeeding, physical activity, post-menopausal non-traumatic fracture, Ashkenazi Jewish, family history of ovarian cancer, mobility) but were not included in our final model may be found in eTable1.

Model Development

We initially considered 17 breast cancer risk factors, recent mammography use, and 6 health conditions in our model (Table 2). History of bilateral oophorectomy and age at menopause were correlated (r=−0.31) and mobility (r=0.57) and limitations with bathing oneself (r=0.31) were correlated with being limited in moderate activities and were not included. The c-statistic for this model was 0.62 (95% CI 0.60–0.63).

Table 2.

Performance of our postmenopausal breast cancer prediction model with all factors included among Nurses’ Health Study participants (n=73,066)- Impact of variables on AICa, c-statistic, and p value.

| Breast Cancer Risk Factors | Fine & Gray Competing Risk Model b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Ages (n=73,066) | Age 55–74 (n=53,362) |

Age 75+ (n=19,704) |

|||

| Full model c-statisticc (95% CI) | 0.6171 (0.6049–0.6292) |

0.6204 (0.6065- 0.6342) |

0.6439 (0.6203- 0.6675) |

||

| Full model AIC | 46522.29 | 34398.05 | 9874.09 | ||

| p-value |

AIC without variable |

c-statistic without variable |

p-value | p-value | |

| Postmenopausal hormone use | <0.0001 | 46586.67 | 0.6036 | <0.0001 | 0.0021 |

|

Number of 1st degree relatives with history of breast cancer and age at diagnosis |

<0.0001 | 46579.94 | 0.6062 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Number of breast biopsies | <0.0001 | 46572.21 | 0.6076 | <0.0001 | 0.0475 |

|

Highest Body Mass Index (BMI) in past 10 years |

<0.0001 | 46548.82 | 0.6106 | 0.0008 | 0.0035 |

| Age at menopause (years) | <0.0001 | 46545.38 | 0.6123 | 0.0031 | <0.0001 |

|

Average alcohol use per day (highest average use in past 10 years) |

0.001 | 46532.20 | 0.6144 | <0.0001 | 0.87 |

| Cigarette use | 0.04 | 46524.84 | 0.6151 | 0.0332 | 0.90 |

| Age at first birth (years) and parity | 0.04 | 46522.78 | 0.6142 | 0.0040 | 0.66 |

| Family history of ovarian cancer | 0.12 | 46522.66 | 0.6169 | 0.10 | 0.76 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 0.14 | 46522.01 | 0.6168 | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| Post-menopausal non-traumatic fracture | 0.51 | 46520.73 | 0.6170 | 0.63 | 0.75 |

| Grandmother with history of breast cancer | 0.54 | 46520.66 | 0.6169 | 0.34 | 0.56 |

| Age at study entry | 0.21 | 46519.70 | 0.6156 | 0.09 | 0.92 |

| Mammogram in past 2 years | 0.68 | 46519.08 | 0.6169 | 0.72 | 0.05 |

| Number of months breastfeeding | 0.32 | 46518.89 | 0.6161 | 0.26 | 0.91 |

| Age at menarche | 0.47 | 46518.87 | 0.6167 | 0.30 | 0.76 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.93 | 46518.43 | 0.6171 | 0.93 | 0.43 |

|

Average physical activity/week (highest average in past 10 years) |

0.47 | 46517.77 | 0.6165 | 0.39 | 0.82 |

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) -is a function of the log-likelihood that adds a penalty of 2 for each additional factor (AIC=-2logLikelihood + 2(number of predictors in the model)

Fine and Gray competing risk regression (CRR) allows for estimating the probability of breast cancer conditional on competing risk-free survival. Specifically, CRR assigns a weight less than one to participants that have experienced a competing risk event or are loss to follow up and these weights decline with increasing time from the competing event and the event of interest.

To improve individualized prediction of mortality, our full model also included significant illnesses (diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke, emphysema, congestive heart failure) and functional limitations.

We kept 8 breast cancer risk factors (the first 8 listed in Table 2) in our final model since they improved the model’s AIC and c-statistic and were significant at p<0.05. We also kept age group in the model since ages 65–74 were significantly associated with increased breast cancer risk and age is strongly associated with death. In addition, we kept illnesses and functional limitations in our model since these factors strongly predicted non-breast cancer death (eTable 2). In addition, we kept mammography use in the model since it was an important predictor of breast cancer among women ≥75 years (p=0.05, Table 2). The c-statistic of the final 16-variable model (Table 3) using CRR was 0.61 (0.64 among women ≥75 years, Table 4). Excluding women with missing information did not change model performance (eTable 3). Using Cox PHR, the model’s c-statistic was 0.61 (0.63 among women ≥75 years, eTable 4).Using Cox PHR, the c-statistic of the model in predicting non-breast cancer death was 0.79 (eTable 2).

Table 3.

Performance of our final predictors in predicting breast cancer using Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression in Nurses’ Health Study (n=73,066) and in Women’s Health Initiative (n=74,887) a, b

| Breast cancer risk factors | NHS (n=73,066) |

WHI (n=74,887) |

P value for the difference in the betasb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | HR | p-value | Beta | HR | p-value | ||

| Age at study entryc | 0.26 | 0.0015 | |||||

| 55–59 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 60–64 | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 1.29 | 0.03 | 0.47 |

| 65–69 | 0.20 | 1.22 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.02 | 0.65 |

| 70–74 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 1.23 | 0.08 | 0.86 |

| 75–80 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 1.24 | 0.08 | 0.83 |

| 80+ | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.32 | −0.07 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 0.30 |

| Postmenopausal hormone use | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| never user | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| past E-alone user, <5 years | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.86 | −0.20 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| past E-alone user, 5+ years | −0.08 | 0.93 | 0.35 | −0.002 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.47 |

| past E+P user, <5 years | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 1.07 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| past E+P user, 5+ years | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 0.06 | 0.85 |

| current E-alone user | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.004 | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.44 | 0.01 |

| current E+P user | 0.81 | 2.25 | <.0001 | 0.50 | 1.65 | <.0001 | 0.047 |

| unknown type of use | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.71 | - | - | - | - |

|

Number of 1st degree relatives with history of breast cancer and age at diagnosis |

<0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| None | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 1, diagnosed age<50 | 0.41 | 1.51 | <.0001 | 0.37 | 1.45 | 0.00 | 0.79 |

| 1, diagnosed age >50/ unknown | 0.27 | 1.31 | <.0001 | 0.34 | 1.41 | <0.0001 | 0.38 |

| 2+, at least 1 diagnosed age <50 | 0.93 | 2.53 | <.0001 | 0.44 | 1.56 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| 2+, 2+ diagnosed age>50/unknown | 0.64 | 1.90 | 0.0001 | 0.74 | 2.09 | <0.0001 | 0.69 |

| History of breast biopsy | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 1 | 0.33 | 1.39 | <.0001 | 0.25 | 1.28 | <0.0001 | 0.25 |

| 2+ | 0.46 | 1.58 | <.0001 | 0.44 | 1.55 | <0.0001 | 0.86 |

|

Highest Body Mass Index (BMI) in past 10 years |

<0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| <20 kg/m2 | −0.47 | 0.62 | 0.01 | −0.57 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.76 |

| 20–24 kg/m2 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 0.19 | 1.21 | 0.0005 | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| 30+ kg/m2 | 0.29 | 1.34 | <.0001 | 0.27 | 1.32 | <0.0001 | 0.85 |

| Unknown | 0.50 | 1.65 | 0.32 | - | - | - | - |

| Age at menopause (years) | <0.0001 | 0.52 | |||||

| <45 | −0.38 | 0.68 | <.0001 | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.50 | 0.003 |

| 45–49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 50–54 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.49 | 0.79 |

| 55+ | 0.17 | 1.18 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.42 | 0.29 |

| Unknown | −0.17 | 0.84 | 0.49 | - | - | - | - |

| Age at first birth (years) and parity | 0.05 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Nulliparous | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.18 | 0.88 |

| <25, 1–2 children/unknown | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| <25, 3+ children | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.54 | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.93 |

| 25–29, 1–2 children/unknown | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.59 | 0.13 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 0.45 |

| 25–29, 3+ children | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0.004 | 0.02 |

| 30+, 1–2 children/unknown | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.67 |

| 30+, 3+ children | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 1.33 | 0.03 | 0.48 |

| unknown age at first birth | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.79 | - | - | - | - |

|

Average alcohol use per day (highest average use in past 10 years) |

0.001 | 0.0014 | |||||

| 0 gm/day | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| 1–4.9 gm/day | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| 5–14.9 gm/day | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 0.06 |

| 15+ gm/day | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.0001 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.003 | 0.33 |

| Unknown | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.62 | - | - | - | - |

| Cigarette use | 0.03 | 0.09 | |||||

| Never | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| Past | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Current | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 0.32 | 0.76 |

| Unknown | −0.71 | 0.49 | 0.32 | - | - | - | - |

| Mammogram in past 2 yearsd | 0.64 | 0.02 | |||||

| No | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.02 | 0.47 |

| Unknown | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.65 | - | - | - | - |

| Comorbidityb | |||||||

| Limited in moderate daily activity | 0.0004 | 0.02 | |||||

| not at all limited | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - |

| limited | −0.17 | 0.85 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 0.02 | 0.0001 |

| Unknown | −0.39 | 0.68 | 0.008 | - | - | - | - |

| Diabetes | 0.12 | 1.12 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.91 | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| Myocardial infarction | −0.29 | 0.75 | 0.09 | −0.24 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 0.85 |

| Stroke | −0.34 | 0.71 | 0.07 | −0.23 | 0.79 | 0.16 | 0.65 |

| Emphysema | −0.10 | 0.90 | 0.27 | −0.12 | 0.89 | 0.20 | 0.90 |

| Congestive heart failure | −0.04 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 0.79 |

| c-statistics (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.60–0.63) | 0.60 (0.58–0.61) | |||||

| AIC | 46503.73 | 55647.02 | |||||

NHS=Nurses’ Health Study included participants that completed the 2004 questionnaire; WHI-ES=Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study which began in 2005- the sample excluded women missing data on variables in our final model.

To test whether betas associated with each risk factor differed between cohorts, we used the normal approximation z-test

We kept age, comorbidities, and functional limitations in our model because they were significant predictors of death.

We kept mammography use in the past two years in the model since it was a significant confounder of breast cancer incidence among women aged 75 and older.

Table 4.

Performance of our final predictors in predicting breast cancer using Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression in Nurses’ Health Study stratified by age.a, b

| Breast cancer risk factors | NHS Ages 55–74 (n=53,362) |

NHS Ages 75+ (n=19,704) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | HR | p-value | Beta | HR | p-value | |

| Age at study entryb | 0.15 | 0.92 | ||||

| 55–59 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| 60–64 | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.14 | - | - | - |

| 65–69 | 0.20 | 1.22 | 0.04 | - | - | - |

| 70–74 | 0.22 | 1.25 | 0.03 | - | - | - |

| 75–80 | - | - | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| 80+ | - | - | - | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.92 |

| Postmenopausal hormone use | <0.0001 | 0.002 | ||||

| never user | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| past E-alone user, <5 years | −0.06 | 0.95 | 0.66 | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.68 |

| past E-alone user, 5+ years | −0.13 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.69 |

| past E+P user, <5 years | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.92 | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.82 |

| past E+P user, 5+ years | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.57 |

| current E-alone user | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 1.75 | 0.0006 |

| current E+P user | 0.80 | 2.22 | <.0001 | 0.91 | 2.49 | 0.003 |

| unknown type of use | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.91 | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.85 |

|

Number of 1st degree relatives with history of breast cancer and age at diagnosis |

<0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| None | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| 1, diagnosed age<50 | 0.38 | 1.46 | 0.0006 | 0.48 | 1.62 | 0.008 |

| 1, diagnosed age >50/unknown | 0.29 | 1.34 | <.0001 | 0.17 | 1.19 | 0.19 |

| 2+, at least 1 diagnosed age <50 | 0.92 | 2.52 | <.0001 | 0.91 | 2.49 | 0.0004 |

| 2+, 2+ diagnosed age>50/unknown | 0.53 | 1.69 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 2.18 | 0.001 |

| History of breast biopsy | <0.0001 | 0.05 | ||||

| 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| 1 | 0.38 | 1.46 | <.0001 | 0.17 | 1.18 | 0.11 |

| 2+ | 0.46 | 1.59 | <.0001 | 0.48 | 1.62 | 0.04 |

|

Highest Body Mass Index (BMI) in past 10 years |

0.0001 | 0.004 | ||||

| <20 kg/m2 | −0.25 | 0.78 | 0.22 | −1.05 | 0.35 | 0.01 |

| 20–24 kg/m2 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 0.17 | 1.18 | 0.009 | 0.24 | 1.28 | 0.02 |

| 30+ kg/m2 | 0.30 | 1.35 | <.0001 | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.07 |

| Unknown | 0.20 | 1.22 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 2.59 | 0.19 |

| Age at menopause (years) | 0.003 | <0.0001 | ||||

| <45 | −0.36 | 0.70 | 0.0007 | −0.44 | 0.64 | 0.05 |

| 45–49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| 50–54 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 0.22 | 1.24 | 0.06 |

| 55+ | 0.08 | 1.08 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 1.61 | 0.006 |

| Unknown | −0.19 | 0.83 | 0.45 | −9.49 | 0 | <.0001 |

| Age at first birth (years) and parity | 0.01 | 0.68 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.80 |

| <25, 1–2 children/unknown | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| <25, 3+ children | −0.10 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 1.28 | 0.19 |

| 25–29, 1–2 children/unknown | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.25 |

| 25–29, 3+ children | −0.08 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.52 |

| 30+, 1–2 children/unknown | 0.24 | 1.28 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 1.40 | 0.14 |

| 30+, 3+ children | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 1.24 | 0.40 |

| unknown age at first birth | −0.12 | 0.89 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.55 |

|

Average alcohol use per day (highest use in past 10 years) |

<0.0001 | 0.89 | ||||

| 0 gm/day | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| 1–4.9 gm/day | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.65 |

| 5–14.9 gm/day | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.66 |

| 15+ gm/day | 0.34 | 1.41 | <.0001 | 0.0002 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Unknown | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 1.25 | 0.34 |

| Cigarette use | 0.027 | 0.90 | ||||

| Never | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Past | −0.08 | 0.92 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.61 |

| Current | 0.17 | 1.19 | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.89 | 0.63 |

| Unknown | −0.93 | 0.40 | 0.36 | −0.43 | 0.65 | 0.67 |

| Mammogram in past 2 years‡ | 0.68 | 0.06 | ||||

| No | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.07 |

| Unknown | 0.12 | 1.12 | 0.48 | −0.23 | 0.79 | 0.48 |

| Comorbidityb | ||||||

| Limited in moderate daily activity | 0.02 | 0.001 | ||||

| not at all limited | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | - |

| limited | −0.10 | 0.91 | 0.10 | −0.34 | 0.71 | 0.0002 |

| Unknown | −0.40 | 0.67 | 0.01 | −0.39 | 0.68 | 0.27 |

| Diabetes | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.07 |

| Myocardial infarction | −0.16 | 0.85 | 0.45 | −0.50 | 0.61 | 0.09 |

| Stroke | −0.25 | 0.78 | 0.31 | −0.44 | 0.65 | 0.14 |

| Emphysema | −0.10 | 0.90 | 0.34 | −0.06 | 0.94 | 0.71 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.11 | 1.12 | 0.55 | −0.18 | 0.83 | 0.41 |

| c-statistics (95% CI) | 0.62 (0.60–0.63) | 0.64 (0.62–0.66) | ||||

| AIC | 34383.02 | 9845.98 | ||||

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) -is a function of the log-likelihood that adds a penalty of 2 for each additional factor.

Fine and Gray competing risk regression (CRR) allows for estimating the probability of breast cancer conditional on competing risk-free survival. Specifically, CRR assigns a weight less than one to participants that have experienced a competing risk event or are loss to follow up and these weights decline with increasing time from the competing event and the event of interest.

External Validation

Calibration

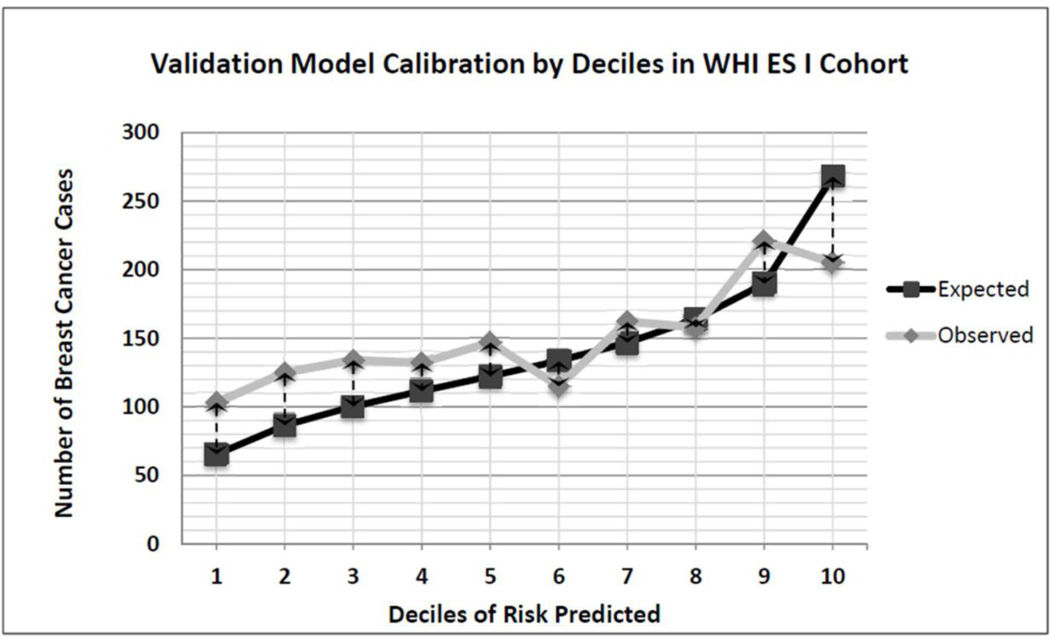

Figure 2 presents the calibration graph and eTable 5 reports the E/O ratio and 95% confidence interval for each risk decile. On average, our model under predicted breast cancer in WHI-ES by 8% (E/O 0.92 [95% CI 0.88–0.97], Table 5); however, the model tended to predict risk accurately for women at higher risk deciles. Also, stratifying by age, we found that the model accurately predicted breast cancer among women 55–74 years on average (E/O 0.96 [0.91–1.02]) but under predicted breast cancer by 17% on average among women ≥75 years (E/O 0.83 [0.76–0.91]).

Figure 2.

Model calibration by Decile of 5-Year Breast Cancer Risk among Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study Participants (n=74,887).

Table 5.

Calibration and Discrimination of our Nurses’ Health Study model among Women’s Health Initiative-Extension Study Participants (n=74,887).a

| CALIBRATION | |||

| Overall |

55–74 yearsb |

75+ years | |

| N | 74,887 | 53,829 | 21,058 |

|

E/O 95% CI |

E/O 95% CI |

E/O 95% CI |

|

| Expected/observed ratios (95% CI) over 5-yearsb | 0.92 (0.88–0.97) |

0.96 (0.91–1.02) |

0.83 (0.76–0.91) |

| DISCRIMINATION | Overall | 55–74 | 75+ years |

| c-statistic 95% CI |

c-statistic 95% CI |

c-statistic 95% CI |

|

| Using the 16-variable model in WHI-ES with NHS coefficientsc |

0.57 (0.55–0.58) |

0.56 (0.55–0.57) |

0.58 (0.56–0.60) |

Nurses’ Health Study included participants that completed the 2004 questionnaire. The Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study began in 2005; we excluded women missing data on variables in our final model.

We compared the expected (E) number of breast cancers based on our model’s estimates from NHS to the observed number (O) in WHI-ES. To determine the 95% CI of the E/O ratios, we used the Poisson variance of the logarithm of the observed number of cases.

We used the betas associated with each risk factor from NHS to determine a breast cancer risk estimate for each woman in WHI-ES. We imputed these risk scores into Mandrekar et al.’s survival c-statistic MACRO to determine our model’s c-statistic or area under the receiver operating characteristic curve and its standard error in WHI-ES.[26, 27]

Discrimination

Our model’s c-statistic was 0.57 (0.55–0.58) in WHI-ES (0.58 [0.56–0.60]) among women ≥75 years). Limiting the WHI-ES sample to non-Hispanic whites did not improve model performance.

Comparing risk factors between cohorts

Several risk factors had different effects on developing breast cancer in WHI-ES than in NHS, including: age <45 at menopause, being age 25–29 at first birth with ≥3 children, past cigarette use, current hormone therapy use, diabetes, and having a functional limitation (Table 3). The effect of having ≥2 first degree relatives (at least one <50 years) also tended to differ between cohorts.

Clinical Application

Table 6 provides example outputs from our model for women with different breast cancer risk factors and health characteristics. In these examples, we show how accounting for comorbidity and functional limitations leads to lower risk estimates for women while considering obesity and other behaviors associated with increased breast cancer risk leads to higher risk estimates. eTable 6 presents a questionnaire patients could use to complete the model.

Table 6.

Example 5-year breast cancer risk estimates for women with different risk factors and health characteristics using our model, BCRAT, and BCSCa, b

| Our model | BCRAT | BCSCc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women with different breast cancer risk factors and health characteristics: |

63 Year old |

77 year old |

63 Year old |

77 year old |

63 year old |

| No risk factors* | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| 2+ family members (1 <50 years at diagnosis) | 3.1% | 3.2% | 5.8% | 6.4% | 1.3% |

| 2+ family members (1 <50 years at diagnosis) + myocardial infarction (MI) |

2.3% | 2.4% | 5.8% | 6.4% | 1.3% |

| 2+ family members (1 <50 years at diagnosis) + MI + limitation in moderate activities |

2.0% | 2.0% | 5.8% | 6.4% | 1.3% |

| History of 2 or more breast biopsies | 1.9% | 2.0% | 2.1% | 2.3% | 1.3% |

| History of 2 or more breast biopsies + MI | 1.4% | 1.5% | 2.1% | 2.3% | 1.3% |

| History of 2 or more breast biopsies + MI + limitation in moderate activities |

1.2% | 1.3% | 2.1% | 2.3% | 1.3% |

| >1 drink per day on average | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| >1 drink per day on average + MI | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| >1 drink per day on average + MI + limitations in moderate activities |

1.0% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

|

2+ family members (1<50 years at diagnosis) and 2+ breast biopsies |

4.8% | 5.0% | 9.2% | 10.2% | 1.9% |

| 2+ family members (1<50) and 2+ breast biopsies + MI | 3.6% | 3.8% | 9.2% | 10.2% | 1.9% |

| 2+ family members (1<50) and 2+ breast biopsies +MI + limitation in moderate activities |

3.1% | 3.2% | 9.2% | 10.2% | 1.9% |

| BMI 30+, >1 drink on average/day and current smoker | 2.4% | 2.5% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| BMI 30+, >1 drink on average/day, and current smoker +MI | 1.8% | 1.9% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| BMI 30+, >1 drinks on average per day, and current smoker +MI +limitation in mod activities |

1.6% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.9% |

Abbreviations: BCRAT=Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool[49]; BCSC=Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Model[5]

Unless otherwise stated we assumed a woman had never used hormones, did not have a family history of breast cancer, never had a breast biopsy, never smoked, did not drink alcohol, had a BMI of 20–24 kg/m2, was age 20–25 at first birth with 1–2 children, was 14 at age at menarche, had fatty breasts, had a mammogram in the past 2 years, did not have significant illness, and was not limited in moderate daily activities.

We do not provide values for a 77 year old woman using BCSC since the BCSC model does not apply to women >74.

DISCUSSION

We developed a novel model for estimating postmenopausal breast cancer risk that considers health behaviors and accounts for individualized competing risks of non-breast cancer death. When we examined model performance in WHI-ES, on average the model accurately predicted breast cancer among women 55–74 years but under predicted breast cancer among women ≥75 years, likely due to greater differences in health characteristics and mammography use in these two age groups. In addition, the model tended to predict risk more accurately for women at higher risk. While model discrimination was modest (c-statistic 0.61), model performance was similar to other commonly used breast cancer prediction models (e.g., BCRAT).[29] Although we used competing risk regression for model development, using proportional hazards regression led to the same overall c-statistic for the model among women 55–74, likely because only 3.5% of women 55–74 years experienced non-breast cancer death in 5 years. Among women ≥75 years, of whom 15% experienced non-breast cancer death in 5 years, using competing risk regression resulted in a higher c-statistic (c-statistic 0.64) than using Cox PHR (c-statistic 0.63), suggesting using CRR is important when death from competing risks is more common. Our innovative model may be particularly useful for assessing breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women with comorbidity and functional limitations and in helping postmenopausal women account for their health behaviors when assessing their breast cancer risk.

Our model has excellent face validity in that the hazard ratio associated with each risk factor is consistent with prior data.[1, 30, 31] The only exception is that past smokers had a non-significant lower risk of breast cancer than non-smokers, possibly because 75% of NHS participants quit smoking >15 years before the start our study and their past cigarette use may no longer affect their risk.[32] Also, smoking is associated with greater risk of non-breast cancer death which CRR accounts for in estimating the cumulative incidence of breast cancer. Of note, some factors commonly associated with breast cancer risk were not associated with risk in our model. This could be due to the low prevalence of the risk factor in NHS (e.g., ovarian cancer family history) or that the risk factor is not strongly associated with postmenopausal breast cancer risk (e.g., age at menarche).[1, 30]

Few prediction models have been tested in populations different from the one in which it was developed, and those that are often perform less well. Our model is no exception. While our model accurately predicted breast cancer among women 55–74 years on average, it under predicted breast cancer among women ≥75 years in WHI-ES. Recommendations for use of mammography screening after age 74 are mixed and there is variable mammography use among older women.[36, 37] Also, WHI-ES participants that had previously participated in the hormone therapy trials were asked to undergo mammography for the first two years of WHI-ES.[38] Possibly as a result, fewer older NHS participants than WHI-ES participants underwent mammography during follow-up (data not shown).

There were other important differences between the WHI-ES and NHS cohorts. WHI-ES is more racially and ethnically diverse than NHS and, although none are currently confirmed, there may be different relationships between model risk factors and breast cancer incidence by race/ethnicity. Also, NHS participants were more likely to die in 5-year follow-up than WHI-ES participants. In addition, WHI-ES participants were less likely to be <45 at menopause and NHS participants <45 at menopause were much less likely to develop breast cancer than WHI-ES participants <45 at menopause. To participate in WHI’s estrogen alone trial a prior hysterectomy was required. As women not uncommonly undergo bilateral oophorectomy along with hysterectomy, a younger average age at menopause for WHI-ES participants could have developed. In post-hoc analyses, we examined the interaction between age of menopause and type of menopause in NHS but we did not find important interactions (only the missing indicator was significant). Also, WHI-ES uses age 45 rather than age 50 as a cut-off for having a family member diagnosed with breast cancer at a young age which may have led to higher risk estimates for family history of breast cancer among relatives diagnosed at an older age in WHI-ES. Family history of breast cancer was assessed on average eight years before WHI-ES began which may also have led to under-ascertainment in WHI-ES. In addition, similar to other studies, we found that current estrogen alone use was associated with increased breast cancer risk in NHS but not WHI-ES.[39, 40] This finding has been attributed to shorter use of estrogen alone and having started estrogen years past menopause in WHI. In WHI’s estrogen alone trial, the mean age at initiation of estrogen was 64 years and median follow-up was only 7.1 years.[39–41] Finally, 847 NHS participants (1.2%) compared to 92 (0.1%) WHI-ES participants remained alive but did not complete a follow-up questionnaire; breast cancer may have been missed among these women.

Our model had similar, modest ability to discriminate which postmenopausal women developed breast cancer as the commonly used BCRAT.[42–44] Although IBIS has been shown to have better discrimination than BCRAT among women with family history of breast cancer;[45] IBIS’s performance has not been tested in a large cohort that includes many women at average risk. Prediction models that include breast density such as BCSC tend to show higher discrimination than BCRAT and our model.[5, 46, 47] However, while the overall c-statistic of the BCSC model was 0.66, its age-adjusted c-statistic was 0.62 and BCSC is not applicable for women >74 years. [5] As an example of how our model may be useful, consider a 63 year old woman with history of MI and 2 first degree relatives with breast cancer. Using BCRAT her estimated 5-year risk of breast cancer is 5.8%; with our model that considers her health it is only 2.3% (Table 6).[2] Of note, BCSC estimates her risk at 1.3% likely because BCSC is known to underestimate risk among women with strong family history of breast cancer.[5]

Since our model could be useful to clinicians and postmenopausal women, we plan to make it available on the web and/or as a mobile application.[11] However, first we plan additional analyses. While our model’s c-statistic in predicting non-breast cancer death was 0.79, our model was not optimized to predict non-breast cancer death. As a next step, we will incorporate prediction of non-breast cancer death into the model so that women may consider their risk of breast cancer in relation to their risk of non-breast cancer death when making clinical decisions. This would require us to consider breast cancer death as a competing risk to non-breast cancer death and we would start the model selection process anew. We also plan to test whether using Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) estimates for baseline breast cancer incidence rather than baseline breast cancer incidence rates from NHS improves model performance.

In summary, we developed a novel model that allows users to assess breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women while taking into account their health behaviors and competing risk of non-breast cancer death. Next steps include optimizing the model to predict non-breast cancer death and making the model available for clinical use. Accounting for older women’s competing risk of mortality is necessary when assessing their breast cancer risk and making decisions around breast cancer screening and prevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. In addition, this study was approved by the Connecticut Department of Public Health (DPH) Human Investigations Committee. Certain data used in this publication were obtained from the DPH.

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C. We would also like to thank the following WHI INVESTIGATORS for their help with this project: Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Dale Burwen, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller Clinical Coordinating Center: Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker We would also like to thank Jonathan Yee for his help with data entry for this manuscript. NOTES: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

FUNDING: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG041860), an NHS cohort infrastructure grant (UM1 CA186107), and an NHS program project grant (P01 CA87969).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- BCRAT

Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool

- BCSC

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium model

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CRR

Competing risk regression

- E/O

Expected to observed ratio

- MI

Myocardial Infarction

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- PHR

Proportional hazards regression

- SEER

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results

- WHI

Women’s Health Initiative Study

- WHI-CT

Women’s Health Initiative Clinical Trials

- WHI-ES

Women’s Health Initiative Extension Study

- WHI-OS

Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study

Footnotes

ETHICAL STANDARDS: The experiments comply with current US laws.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work was presented in part at the 9th annual meeting of the Cancer and Primary Care Research International Network April 28th, 2016 in Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1336–1347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson HD, Smith ME, Griffin JC, Fu R. Use of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):604–614. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, Mulvihill JJ. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyrer J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat Med. 2004;23(7):1111–1130. doi: 10.1002/sim.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):337–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, Widera EW, Smith AK. Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307(2):182–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP. Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):783–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepe MS, Mori M. Kaplan-Meier, marginal or conditional probability curves in summarizing competing risks failure time data? Stat Med. 1993;12(8):737–751. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780120803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, McCarthy EP, Ngo LH. Predicting breast cancer mortality in the presence of competing risks using smartphone application development software. International Journal of Statistics in Medical Research. 2015;4:322–330. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Glas NA, Kiderlen M, Vandenbroucke JP, de Craen AJ, Portielje JE, van de Velde CJ, Liefers GJ, Bastiaannet E, Le Cessie S. Performing Survival Analyses in the Presence of Competing Risks: A Clinical Example in Older Breast Cancer Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health. 1997;6(1):49–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Sampson L, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123(5):894–900. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Egan KM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Baron JA, Storer BE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Fracture history and risk of breast and endometrial cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(11):1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.11.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Willett WC. Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1407–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuhouser ML, Aragaki AK, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Chlebowski R, Carty CL, Ochs-Balcom HM, Thomson CA, Caan BJ, Tinker LF, et al. Overweight, Obesity, and Postmenopausal Invasive Breast Cancer Risk: A Secondary Analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(5):611–621. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook NR, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA. Mammographic screening and risk factors for breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1422–1432. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Ales KL, Simon R, MacKenzie CR. Why predictive indexes perform less well in validation studies. Is it magic or methods? Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(12):2155–2161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43(6):607–615. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163658.65008.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. Index to predict 5-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older using data from the National Health Interview Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1115–1122. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295(7):801–808. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.deLeeuw J. “Introduction to Akaike (1973) information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle”. In: Kotz S, Johnson NL, editors. Breakthroughs in Statistics I. Springer; 1992. pp. 599–609. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):515–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daly L. Simple SAS macros for the calculation of exact binomial and Poisson confidence limits. Comput Biol Med. 1992;22(5):351–361. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(92)90023-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statisical methods in diagnostic medicine using SAS software. [Accessed June 15, 2016]; [ http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi30/211-30.pdf]

- 27.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB. Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med. 2004;23(13):2109–2123. doi: 10.1002/sim.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Tutorial in biostatistics multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in medicine. 1996;15:361–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schonberg MA, Li VW, Eliassen AH, Davis RB, LaCroix AZ, McCarthy EP, Rosner BA, Chlebowski RT, Rohan TE, Hankinson SE, et al. Performance of the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool Among Women Age 75 Years and Older. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(3) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweeney C, Blair CK, Anderson KE, Lazovich D, Folsom AR. Risk factors for breast cancer in elderly women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(9):868–875. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shantakumar S, Terry MB, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Millikan RC, Moorman PG, Neugut AI, Gammon MD. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk among older women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102(3):365–374. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo J, Margolis KL, Wactawski-Wende J, Horn K, Messina C, Stefanick ML, Tindle HA, Tong E, Rohan TE. Association of active and passive smoking with risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neilson HK, Friedenreich CM, Brockton NT, Millikan RC. Physical activity and postmenopausal breast cancer: proposed biologic mechanisms and areas for future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):11–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedenreich CM, Bryant HE, Courneya KS. Case-control study of lifetime physical activity and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):336–347. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eliassen AH, Hankinson SE, Rosner B, Holmes MD, Willett WC. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(19):1758–1764. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. W-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Royce TJ, Hendrix LH, Stokes WA, Allen IM, Chen RC. Cancer screening rates in individuals with different life expectancies. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1558–1565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHI Protocols and Study Consents. [Accessed June 18, 2016]; [ https://www.whi.org/researchers/studydoc/SitePages/Protocol%20and%20Consents.aspx]

- 39.Beral V, Reeves G, Bull D, Green J. Breast cancer risk in relation to the interval between menopause and starting hormone therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(4):296–305. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fournier A, Mesrine S, Dossus L, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Chabbert-Buffet N. Risk of breast cancer after stopping menopausal hormone therapy in the E3N cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145(2):535–543. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2934-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Gass M, Bluhm E, Connelly S, Hubbell FA, Lane D, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):476–486. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70075-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schonfeld SJ, Pee D, Greenlee RT, Hartge P, Lacey JV, Jr, Park Y, Schatzkin A, Visvanathan K, Pfeiffer RM. Effect of changing breast cancer incidence rates on the calibration of the Gail model. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2411–2417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. External validation of an index to predict up to 9-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 59(8):1444–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Lane DS, Aragaki AK, Rohan T, Yasmeen S, Sarto G, Rosenberg CA, Hubbell FA. Predicting risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women by hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(22):1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amir E, Evans DG, Shenton A, Lalloo F, Moran A, Boggis C, Wilson M, Howell A. Evaluation of breast cancer risk assessment packages in the family history evaluation and screening programme. J Med Genet. 2003;40(11):807–814. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.11.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Ziv E, Kerlikowske K. Mammographic breast density and the Gail model for breast cancer risk prediction in a screening population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94(2):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-5152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J, Pee D, Ayyagari R, Graubard B, Schairer C, Byrne C, Benichou J, Gail MH. Projecting absolute invasive breast cancer risk in white women with a model that includes mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(17):1215–1226. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.What is a standard drink? [Accessed June 15, 2016]; [ http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/pocketguide/pocket_guide2.htm]

- 49.Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool Source Code. [Accessed June 27, 2016]; Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/download-source-code.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.