Abstract

Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma (PPSS) is a rare disease. Diagnosis is made postoperatively following resection of the tumor. We describe the case of a 39‐year‐old non‐smoking woman whose chest imaging revealed a heterogeneous mass (5.4 cm × 4.6 cm), with soft tissue density in the right upper lobe and pleural effusion in the right hemithorax. The tumor was enhanced on a computed tomography scan, in which enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes compressing the adjacent superior vena cava was observed. Endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS‐TBNA) was then performed, which demonstrated PPSS, subsequently confirmed by immunohistochemistry and the detection of a SYT‐SSX fusion gene. We believe that a diagnostic approach of EBUS‐TBNA for lung sarcoma would provide helpful information to clinicians.

Keywords: Diagnosis, endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration, primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma, SYT‐SSX fusion gene

Introduction

Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma (PPSS) is very uncommon, comprising only 0.5% of all primary lung malignancies.1, 2 A diagnosis of PPSS is usually made postoperatively following resection of the tumor. Endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS‐TBNA) is an effective tool used in lung cancer diagnosis and staging.3 Herein, we describe the unique clinical application of EBUS‐TBNA for a diagnosis of PPSS, confirmed by immunohistochemistry and the detection of a SYT‐SSX fusion gene.

Case report

A 39‐year‐old non‐smoking woman presented to our hospital with a one‐year history of chest tightness, which had worsened with a cough for approximately a week. The patient did not experience fever or back pain. She denied trauma or prior surgery, and had no known toxic exposure or family history of malignancy. A physical examination revealed nothing of significance in the chest, abdominal region, or in the extremities.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed a heterogeneous mass (5.4 cm × 4.6 cm), with soft tissue density in the superior lobe of the right lung and pleural effusion in the right hemithorax (Fig 1a). Moderate tumor enhancement, with enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes compressing the adjacent superior vena cava, was also observed (Fig 1b). Exudate and morphological changes to the cells were determined upon analysis of the patient's right‐sided pleural effusion. Single‐photon emission CT of the bones showed a slight increase of radioactive tracer in the right fifth rib, while magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was normal.

Figure 1.

(a) Chest computed tomography revealed a heterogeneous mass in the superior lobe of the right lung and pleural effusion in the right hemithorax. (b) The tumor was enhanced, compressing the adjacent superior vena cava. (c) Fiberoptic bronchoscopy showed a neoplasm in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe involving the opening of the apical segments. (d) Endobronchial ultrasonography showed an abnormally low echo signal next to the front wall of the right main bronchus, upon which endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration sampling was performed.

A neoplasm was observed in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe involving the opening of apical segments on fiberoptic bronchoscopy (Fig 1c). Endobronchial ultrasonography was performed, and an abnormally low‐echo signal next to the front wall of the right main bronchus was identified, upon which EBUS‐TBNA sampling was performed using an Olympus 21‐gauge needle (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA; Fig 1d).

A number of heterotypic cells were seen during fiberoptic bronchoscope brushing, and small malignant tumor cells were indicated in the histological and pathological examination (Fig 2a), consistent with poorly differentiated sarcoma. When combined with immunohistochemistry, staining was positive for vimentin, B‐cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl‐2), cluster of differentiation (CD) 99 (Fig 2b–d) and CD56, and negative for leukocyte common antigen, cytokeratin, Syn, S‐100, CD34, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and thyroid transcription factor‐1. Subsequent fusion gene detection by reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) showed the SSX‐SYT gene to be positive in the lesion identified by ultrasound, and negative in the peripheral blood (Fig 3).

Figure 2.

Pathological examination. (a) Small, malignant tumor cells were shown on hematoxylin–eosin staining (magnification ×200). Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for (b) vimentin (magnification ×200), (c) B‐cell lymphoma 2 (magnification ×200), and (d) cluster of differentiation 99 (magnification ×200).

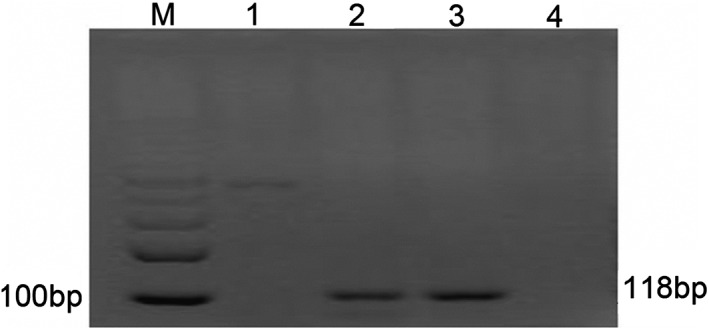

Figure 3.

Positive detection of the SYT‐SSX fusion gene. Reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction analysis of total RNA from a patient with synovial sarcoma was performed using SYT‐SSX primers. Lane 1: the patient's peripheral blood sample; lane 2: a sample of the patient's ES lesions; lane 3: positive control; lane 4: negative control; and M: marker of SYT‐SSX fusion gene.

Next‐generation sequencing (Illumina HiSeq NGS 4000, tissue depth of 1000; Illumina Inc., Madison, WI, USA) showed that EGFR, ALK, BRAF, BRCA1, and KIT were all negative, and there was no powering gene expression. On the basis of these findings, we diagnosed the tumor as a monophasic PPSS.

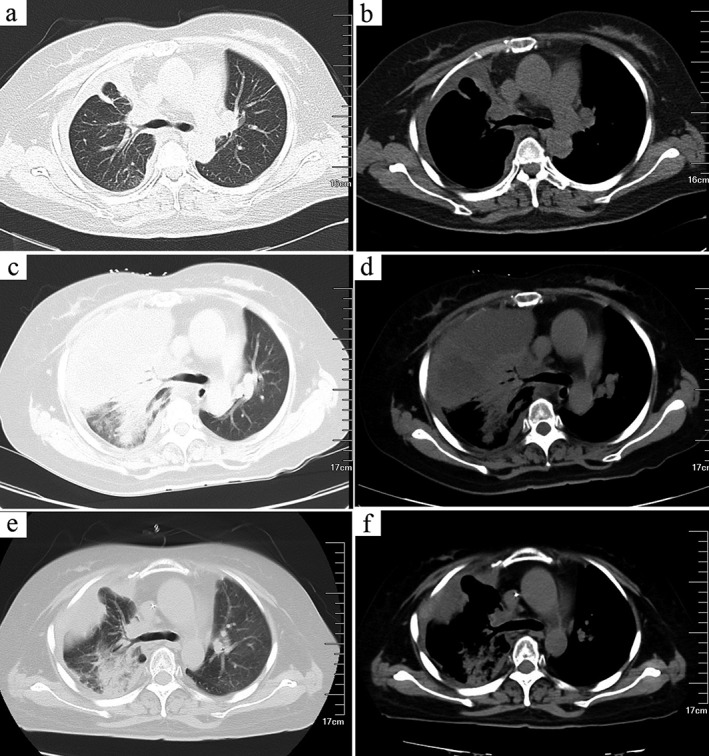

The patient underwent local radiotherapy (54 Gy/26 f). The primary lesion was significantly reduced and the chest tightness and coughing relieved (Fig 4a,b). Unfortunately, her condition deteriorated three months later, and a follow‐up chest CT taken on 17 October showed that the tumor had increased in size (Fig 4c,d). The patient received a cycle of chemotherapy (ifosfamide 1.2 g/m2 on days 1–5, epirubicin 50 mg/m2, on day 1). Despite severe bone marrow suppression, the tumor appeared smaller than it had previously on a subsequent chest CT taken on 14 November (Fig 4e,f). Unfortunately, after six months the patient was lost to follow‐up.

Figure 4.

Imaging findings at different periods. The size of the mass reduced significantly following radiotherapy: (a) lung window, (b) mediastinum window. An increase in tumor size was shown on chest computed tomography (CT): (c) lung window, (d) mediastinum window). The tumor appeared smaller after chemotherapy on chest CT: (e) lung window, (f) mediastinum window.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a rare tumor, accounting for 5–10% of all soft tissue sarcomas. It occurs most frequently in the extremities of adolescents and young adults, and also in parts of the head, neck, eyelids, and thoracic and abdominal cavities, as well as in the temporomandibular joint, infratemporal fossa, and pulmonary valve.4 The lung is an extremely unusual anatomical location for SS. Primary occurrence in the mediastinum is also quite rare.5 A diagnosis of PPSS depends on good histopathological and immunohistochemical results, as well as SYT‐SSX gene detection.6

The main clinical manifestations include chest pain, dyspnea, coughing, and hemoptysis. Patients can also develop fever or pneumothorax. A typical CT finding of PPSS is a well‐circumscribed large mass with soft tissue density in the lung. The mass may show mild or moderate enhancement, with or without enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes. Ipsilateral pleural effusion with calcification is common in this rarely seen tumor. Overall, the clinical and imaging findings are not specific.

In immunohistochemical studies, PPSS is often found positive for cytokeratin, EMA, Bcl‐2 and vimentin, and negative for S‐100, desmin, smooth muscle actin, and vascular tumor markers. A characteristic balanced translocation between chromosomes X and 18, t (X; 18) (p11.2; q11.2) is shown in most cases of SS, and, as in our case, is confirmed by SYT‐SSX gene detection.

Current treatment for PPSS primarily consists of surgical resection, followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma is controversial. The prognosis for PPSS is poor, and there is an overall five‐year survival rate of 50%. In our case, the patient received sequential radiotherapy and chemotherapy, with initial improvement.

Endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration is an effective and safe method of diagnosing unknown mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy, and allows the sampling of mediastinal, hilar, and proximal endobronchial masses.7, 8 It was first applied to diagnose and stage lung cancer, but rapidly evolved to diagnose other benign and malignant diseases, including lymphoma, nodal infection, and tuberculosis.9 Adequate and meaningful results can be obtained with EBUS‐TBNA: its culture‐positive rates are higher than those of other methods; its use directs subsequent management strategy; and the procedure is less invasive and painful and more facilitative of rapid postoperative recovery than surgery.

In summary, PPSS is an extremely rare tumor. Our case study illustrates the use of EBUS‐TBNA in the diagnosis of PPSS as a minimally invasive technique, rather than having to resort to more invasive surgical biopsy.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. J Francis Turner Jr., University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, is thanked for his expert contribution and critical analysis of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Falkenstem‐Ge RF, Kimmich M, Grabner A et al. Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma: A rare primary pulmonary tumor. Lung 2014; 192: 211–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hashimoto M, Kondo N, Takuwa T, Matsumoto S, Hasegawa S. A surgical case of primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma confirmed by the detection of a SYT‐SSX1 fusion gene. Int Canc Conf J 2014; 3: 128–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yasufuku K, Chiyo M, Sekine Y et al. Real‐time endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Chest 2004; 126: 122–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eilber FC, Dry SM. Diagnosis and management of synovial sarcoma. J Surg Oncol 2008; 97: 314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rea G, Somma F, Valente T, Antinolfi G, Di Grezia G, Gatta G. Primary mediastinal giant synovial sarcoma: A rare case report. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 2015; 46: 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bode‐Lesniewska B, Hodler J, von Hochstetter A, Guillou L, Exner U, Caduff R. Late solitary bone metastasis of a primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma with SYT‐SSX1 translocation type: Case report with a long follow‐up. Virchows Arch 2005; 446: 10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tournoy KG, Rintoul RC, van JP M et al. EBUS‐TBNA for the diagnosis of central parenchymal lung lesions not visible at routine bronchoscopy. Lung Cancer 2009; 63: 45–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boujaoude Z, Dahdel M, Pratter M, Kass J. Endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2012; 19: 9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Korrungruang P, Oki M, Saka H et al. Endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration is useful as an initial procedure for the diagnosis of lymphoma. Respir Investig 2016; 54: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]