Short abstract

NICE guidelines are evidence based but will need regular updating

Faced with a plethora of guidelines, doctors in primary and secondary care may well ask, why another guideline and particularly a guideline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and how is it going to affect practice?

Guidelines from the Global Initiative in Obstructive Lung Disease were updated in 2003.1 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) published a guideline earlier this year.2 New guidelines from the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society appeared recently (www.thoracic.org/copd). The existence of so many guidelines reflects the increasing recognition of the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease both on patients and on healthcare resources. Whereas the condition was considered to have few therapeutic options previously, it is now considered treatable, and over the past five years increasing evidence supports pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. This article discusses the guideline published for NICE by the National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions and many members of the British Thoracic Society and makes some comparisons with other guidelines. The 1997 British Thoracic Society guidelines needed updating,3 which is what the NICE guideline does. It is truly evidence based, wide ranging, and deals with diagnosis, assessment of severity, and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

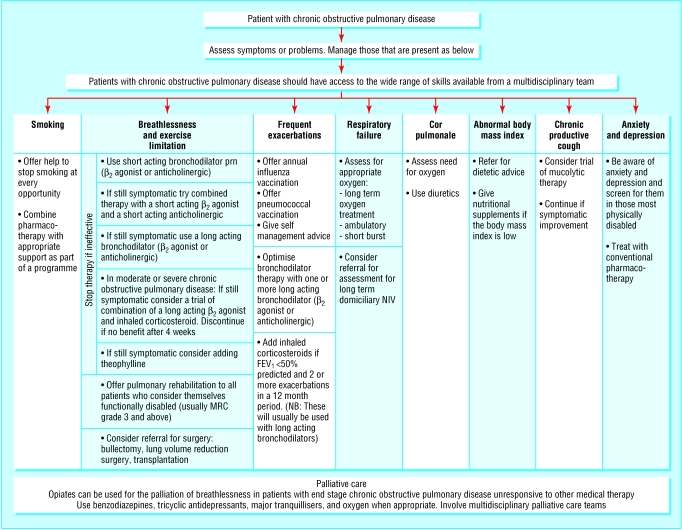

The evidence on which the recommendations in the NICE guideline are based is presented in a standard format for each section, indicating which studies were reviewed, with evidence based statements from these studies followed by consensus statements from the guidelines development group and the recommendation—which has resulted in a lengthy document. However, the key priorities are summarised with diagnostic and treatment algorithms (figure). Evidence about health economics is included, and the literature review is to high standards.

Figure 1.

Management of stable chronic pulmonary disease. Adapted from Thorax 2004;59(suppl 1)

So what is in the NICE guideline that will influence a change in practice? Several aspects of the diagnosis and assessments of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease depart from other guidelines (including the guidelines from the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society guidelines) by stating that a diagnosis of the condition can be based on a good history with the confirmation of airflow limitation by spirometry. No recommendation is made to measure the change in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after inhaled bronchodilator or a short trial of corticosteroids. This is perhaps the most controversial aspect of the guideline. Such tests are stated to be of poor reproducibility in individual patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the presence or absence of a small response to a bronchodilator fails to predict the response to future treatment. The guideline, however, ignores the importance of post-bronchodilator spirometry as the method to define chronic airflow obstruction as being not fully reversible and the usefulness of a large bronchodilator response (usually more than 400 ml) as a feature suggestive of underlying asthma. A reversibility test, usually after administering a nebulised bronchodilator, is also useful to determine the best spirometric value for individual patients.

The NICE guideline also departs from the traditional approach for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is usually based on an assessment of severity usually measured as the level of percent predicted FEV1. The NICE guideline uses symptoms rather than the degree of airflow limitation to determine treatment. The acceptance in this guideline that the FEV1 is an important aspect in the assessment of severity but not an exclusive measure of severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is also welcome, and the need to assess symptoms, exercise tolerance, and systemic features such as the measurement of the body mass index recognises recent evidence.4,5 The guideline suggests that health status should be part of the assessment of a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but no details are provided on the health status tool that should be used or the practicality of measuring health status in these patients.

The NICE guideline scores best when evidence based pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are assessed. The extensive evidence of the efficacy of long acting bronchodilators and their effectiveness in improving symptoms rather than changing the FEV1 has resulted in recommending these drugs in patients who remain symptomatic despite the use of short acting bronchodilators. An important point is the recommendation to assess the response to therapy in terms of symptoms and exercise tolerance. The use of inhaled corticosteroids is clarified, based on recent evidence that they reduce exacerbations in patients with an FEV1 of less than 50% predicted and a history of one or more exacerbations in the preceding year.

The role of combinations of long acting bronchodilators and corticosteroids is defined less clearly and is already out of date with respect to recently published data6—a problem with all guidelines. This highlights the need to have a mechanism in place for regular updates of guidelines.

A novel statement in the guideline relates to the use of mucolytic drugs, which have not been used or licensed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United Kingdom. A review of the literature indicates that mucolytics, and particularly the mucolytic and antioxidant N-acetylcysteine, are effective in reducing exacerbations and improving symptoms in patients with chronic bronchitis and provides some evidence to support its efficacy in this condition. Again this evidence will soon be out of date with the forthcoming publication of the randomised controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This trial shows no effect of the drug on FEV1 decline but a reduction in overinflation in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in the exacerbation rate in patients who are not treated with inhaled corticosteroids (Marc Decramer, personal communication, 2004).

The role of pulmonary rehabilitation is firmly established in the guideline, and this firm recommendation of its efficacy will hopefully improve the woeful lack of provision of this treatment in the United Kingdom. The provision of oxygen therapy has been updated in line with the advice of the published report by the Royal College of Physicians7 and includes recommendations for ambulatory oxygen, which will hopefully be available for prescription in the very near future.

The advice in the NICE guideline on exacerbations is very similar to recommendations in other guidelines on, for example, the use of oral corticosteroids and of oxygen therapy and antibiotics. Although the lack of evidence for intravenous theophylline is interpreted as being the reason for not altering the practice of giving intravenous theophylline when treatment with bronchodilators fails to show an improvement in an exacerbation, most other guidelines indicate that evidence is lacking for the safe use of theophylline, and it is therefore not recommended.

The effectiveness of non-invasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure, which complicates exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is given prominence, although specific recommendations on when to introduce this treatment are not clear. Nurse led or supported discharge schemes for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are recommended in view of the evidence based on several randomised controlled trials.

The NICE guideline will help to clarify, standardise, and improve treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Hopefully, it will ensure the provision of treatment options such as non-invasive ventilation, supported discharge, and rehabilitation.

Competing interests: WMcN has been reimbursed by Glaxo-SmithKline, and Boehringer-Ingelheim for attending several conferences. He has been paid for speaking at medical conferences organised by GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Zambon. He has received funding for research from Pfizer, GlaxosmithKline, and SMB Pharmaceuticals but not directly related to any of the drugs discussed in the article.

References

- 1.Fabbri LM, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis and management and prevention of COPD. 2003 Update. Eur Respir J 2003;22: 1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax 2004;59(suppl 1): 1-232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.British Thoracic Society Guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1997;52(suppl 5): s1-26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agusti AG. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Novartis Found Symp 2001;234: 242-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendex RA, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;4: 1005-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calverley PM, Boonsawat W, Cseke Z, Zhong N, Peterson S, Olsson H. Maintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2003;22: 912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Physicians. Domiciliary oxygen therapy services clinical guidelines and advice for prescribers. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1999. [PMC free article] [PubMed]