Abstract

Objectives

To explore views of all stakeholders (patients, optometrists, general practitioners (GPs), commissioners and ophthalmologists) regarding the operation of community-based enhanced optometric services.

Design

Qualitative study using mixed methods (patient satisfaction surveys, semi-structured telephone interviews and optometrist focus groups).

Setting

A minor eye conditions scheme (MECS) and glaucoma referral refinement scheme (GRRS) provided by accredited community optometrists.

Participants

189 patients, 25 community optometrists, 4 glaucoma specialist hospital optometrists (GRRS), 5 ophthalmologists, 6 GPs (MECS), 4 commissioners.

Results

Overall, 99% (GRRS) and 100% (MECS) patients were satisfied with their optometrists’ examination. The vast majority rated the following as ‘very good’; examination duration, optometrists’ listening skills, explanations of tests and management, patient involvement in decision-making, treating the patient with care and concern. 99% of MECS patients would recommend the service. Manchester optometrists were enthusiastic about GRRS, feeling fortunate to practise in a ‘pro-optometry’ area. No major negatives were reported, although both schemes were limited to patients resident within certain postcode areas, and some inappropriate GP referrals occurred (MECS). Communication with hospitals was praised in GRRS but was variable, depending on hospital (MECS). Training for both schemes was valuable and appropriate but should be ongoing. MECS GPs were very supportive, reporting the scheme would reduce secondary care referral numbers, although some MECS patients were referred back to GPs for medication. Ophthalmologists (MECS and GRRS) expressed very positive views and widely acknowledged that these new care pathways would reduce unnecessary referrals and shorten patient waiting times. Commissioners felt both schemes met or exceeded expectations in terms of quality of care, allowing patients to be seen quicker and more efficiently.

Conclusions

Locally commissioned schemes can be a positive experience for all involved. With appropriate training, clear referral pathways and good communication, community optometrists can offer high-quality services that are highly acceptable to patients, health professionals and commissioners.

Keywords: Enhanced Optometric Services, Multi-stakeholder perspective, Qualitative mixed methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to describe the views and attitudes of all key stakeholders (patients, optometrists, general practitioners, ophthalmologists and commissioners) on the operation of community-based enhanced optometric services.

The wide range of qualitative methods used comprised patient satisfaction questionnaires validated by follow-up telephone interviews, focus groups and semi-structured telephone interviews.

All those surveyed were active participants in the two schemes studied and their views may not be representative of participants in schemes in general across the UK

Introduction

The need for more cost-effective NHS services is increasingly impacting health policy and service delivery. Ophthalmologists are overstretched and resource-heavy to train, and therefore, alternative models of care are being explored.

In 2005, the Department of Health commissioned a review of the General Ophthalmic Services (GOS)1 which focused on how to support and develop a wider range of community-based eye care services and recommended a three-tiered GOS framework comprising: (a) essential services: provision of the standard sight test, (b) additional services: that is, domiciliary sight tests and (c) enhanced services, such as community referral refinement and management of acute eye conditions.

Across England, enhanced service schemes (ESS) (now known as Community Eyecare Services) within primary care are delivered by optometrists, outside the GOS contract. While schemes are dependent on purpose, the intended outcomes are to help community optometrists and dispensing opticians work collaboratively with local commissioners and/or hospital eye services (HES) to design and add value to local eye health pathways. Aims of ESS include making services accessible for patients who would otherwise have to be managed in hospital, and increasing the cost-effectiveness of services.

ESS are locally commissioned and heavily dependent on existing infrastructure. Establishing effective monitoring strategies for chronic conditions requires the input of service providers and service users. Care plans that place burdens on patients may result in reduced willingness to attend, leading to compromised quality of care.2 3 The health professionals' and patients' views regarding aspects of their condition are not always aligned,4 5 and views of all stakeholders must be considered when commissioning services.

This paper reports on a qualitative study to determine views and attitudes of stakeholders, including patients, regarding two representative ESS: a minor eye conditions scheme (MECS) in South London and a glaucoma referral refinement scheme (GRRS) in Manchester. This study complements our previous qualitative research which investigated the development and implementation of these schemes.6 The current study aims to establish if the schemes met stakeholders' expectations.

Methods

Organisation of the MECS and GRRS

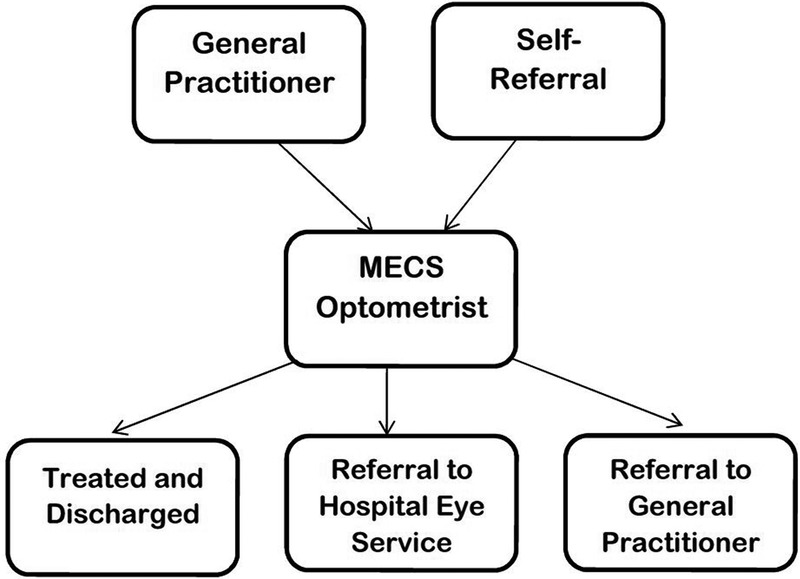

Under the MECS, patients presenting to their general practitioner (GP) with an eye problem and satisfying certain inclusion criteria are referred to specially trained community optometrists. The scheme also allows patients to access MECS optometrists directly. Patients were examined by optometrists within 48 hours and could be either managed within community optometric practice or referred directly to the HES. Patients could also be referred to their GP for systemic investigations (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Minor eye conditions scheme patient pathway.

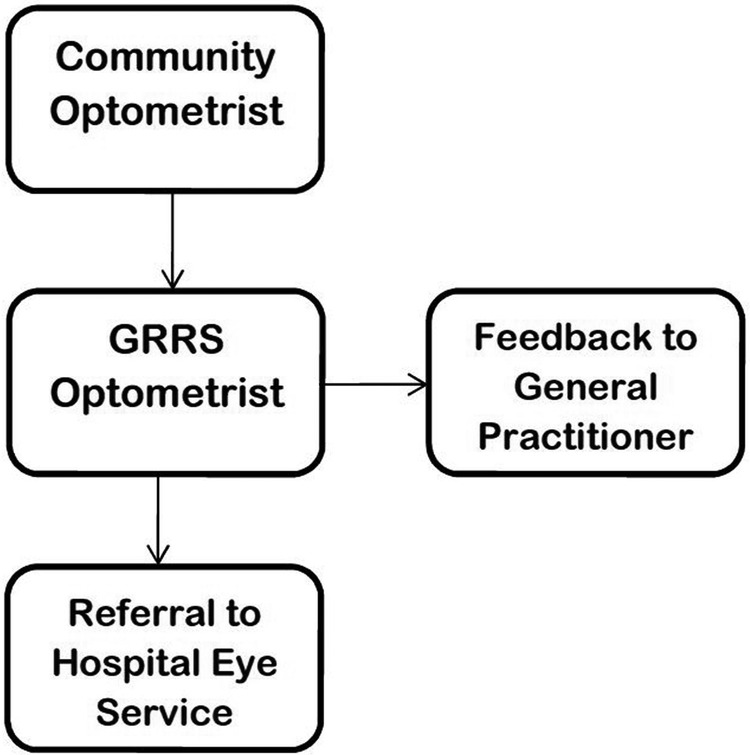

In the GRRS, patients with suspected glaucoma or ocular hypertension following a standard GOS sight test are referred to accredited community optometrists. These accredited optometrists work to an agreed set of referral criteria and, depending on whether or not patients meet these criteria, either refer the patients to the HES or discharge them (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Glaucoma referral refinement scheme patient pathway.

Design, participants and data collection

Four target groups of stakeholders participated, using mixed methods of data collection to maximise response rates and data quality (table 1). The sampling strategy was designed to be inclusive and capture views of healthcare professionals, commissioners and patients. As some groups, for example, ophthalmologists/commissioners, had small numbers, all participants in these groups were included in the sample frame.

Table 1.

Methods of data collection

| MECS |

GRRS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Method of data collection | N | Method of data collection | |

| Patients | 109 | Patient satisfaction survey, validated by follow-up telephone interviews on a random sample | 80 | Patient satisfaction survey, validated by follow-up telephone interviews on a random sample |

| Optometrists | 11 | Focus group | 14 | Focus group |

| Other health professionals | ||||

| GPs | 6 | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 0 | NA |

| Ophthalmologists | 2 | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 3 | Semi-structured telephone interviews |

| Glaucoma specialist optometrists | 0 | NA | 4 | Semi-structured telephone interviews |

| Commissioners | 2 | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 2 | Semi-structured telephone interviews |

Patient satisfaction survey

A questionnaire, adapted from an Ipsos MORI validated GP survey,7 was developed. It comprised questions with multiple choice answers and respondents graded their satisfaction with the scheme. There was one open-ended question for recommendations and an option for respondents to leave their telephone number if they were willing to participate in a further indepth discussion. The questionnaire was almost identical for both schemes, with minor scheme-specific amendments only (copies in online supplementary file).

bmjopen-2016-011934supp1.pdf (138.1KB, pdf)

After their appointment, patients were given a questionnaire to complete and return in a prepaid envelope. Data were collected over a 2-month period for MECS and a 6-month period for GRRS because the number of patients seen per week was fewer than in MECS.

Community optometrists' focus group

Two meetings took place; in November 2014 in London (MECS optometrists) and June 2015 in Manchester (GRRS optometrists). All optometrists in the schemes were invited to participate. Topic guides were devised outlining broad question areas, and their contents were informed by our previous study.6 The guide topics acted only as suggestions; the precise wording of questions used at meetings did not adhere rigidly to the guide scripts, although each topic was addressed in a similar way, nor was the order of the topics fixed (see online supplementary file ‘topic guide’). Prompts were used to introduce topic areas and encourage respondents to elaborate, but the onus was on participants to supply the overall discussion content. Questions were open and ‘non-leading’, although more specific questioning was used, when required, to clarify points made by participants.

bmjopen-2016-011934supp2.pdf (196.8KB, pdf)

Health professionals' (GPs, glaucoma specialist optometrists and ophthalmologists) semi-structured telephone interviews

In addition to community optometrists, both schemes had other health professionals essential to their smooth running. Ophthalmologists were important service users within MECS and GRRS. MECS relies heavily on GPs referring patients into the scheme and GRRS employs hospital-based glaucoma specialist optometrists (known as Optometrist Led Glaucoma Assessment (OLGA) optometrists) as trainers and receivers of referrals from community optometrists. The questionnaire from the previous study6 informed the development of the semi-structured questionnaire used in the current study. For a copy, see the online supplementary file: health professionals' questionnaire. The questionnaire covered:

impacts on current working practice,

meeting expectations,

appropriateness of referrals,

training,

communication.

A purposive sample of GPs from MECS was contacted, including high, medium and low scheme users. Ophthalmologists from MECS and GRRS and OLGA optometrists from GRRS were invited to participate. All questionnaires were completed during a telephone interview and data entered at the point of administration.

Commissioners' semi-structured telephone interviews

Commissioners of MECS and GRRS were contacted and a short semistructured questionnaire was administered by telephone, using the same format as the questionnaire to health professionals, with an emphasis on meeting expectations, cost-effectiveness and continuation of the scheme.

Analysis

Focus groups were audio recorded (with permission from the participants). The dialogue from the recordings was later transcribed and reviewed by the investigators. Data from interviews and focus groups were analysed using framework analysis8 as displayed in table 2. The qualitative software package NVIVO v.10.2 (QSR International, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) was used to organise the thematic framework by refining and condensing the categories that had been manually identified and to identify additional themes for further analysis.

Table 2.

Framework technique used for data analysis8

| Framework technique | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Familiarisation | Reading and re-reading the transcriptions |

| 2 | Identifying a thematic framework | Condense data into categories |

| 3 | Indexing | Codes systematically applied to the data |

| 4 | Charting | Rearranging the data according to the thematic content in a way which allows for a cross case and within case analysis |

| 5 | Mapping and interpretation | Interpretations and recommendations |

Results

All qualitative data were indexed according to themes and questions central to the main research questions. During analysis, sub-themes that emerged were explored and indexed accordingly. Direct quotes from transcripts and interviews were chosen to illustrate key emerging themes.

Patient satisfaction survey

The questionnaire consisted of eight (GRRS) or nine (MECS) multiple choice questions and one open-ended question. There were 109 responses for MECS (∼28% response rate) and 80 (∼21% response rate) for GRRS.

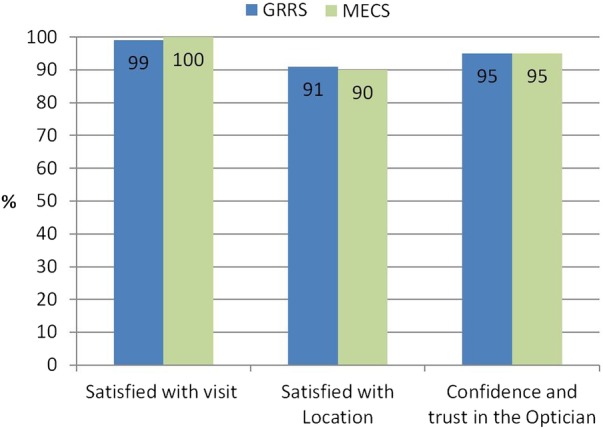

Overall satisfaction results (figure 3) revealed that the vast majority of patients reported satisfaction with their appointment and any subsequent treatment.

Figure 3.

Overall satisfaction.

Ninety-five per cent of participants in both schemes had confidence and trust in their optometrist. The responses to more specific questions about the optometrist's performance are presented in table 3. The vast majority of patients rated as ‘very good’ the time allowed for the examination, the optometrist listening to the patient's concerns, explanations of tests and management, involving the patient in decision-making, and treating the patient with care and concern.

Table 3.

Optometrists' performance as rated by patients

| Very good % |

Good % |

Neither good nor poor % |

Poor % |

Very poor % |

Missing data % |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRRS | MECS | GRRS | MECS | GRRS | MECS | GRRS | MECS | GRRS | MECS | GRRS | MECS | |

| a. Giving you enough time | 93 | 90 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| b. Listening to you | 95 | 89 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| c. Explaining tests and treatments | 88 | 84 | 10 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| d. Involving you in decisions about your care | 90 | 84 | 6 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| e. Treating you with care and concern | 90 | 91 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

MECS allows for self-referral; therefore, these patients were asked if they would recommend the service to family and friends, and 99% of patients would. In both schemes, there was one open-ended question asking how the scheme could be improved. Nineteen per cent of GRRS and 16% of MECS patients responded. The majority of patients in both schemes merely reiterated how happy they were with their visit and treatment, and 4% of MECS patients wanted the scheme to be better publicised.

Optometrists' focus groups

Overall impression of the schemes

Attendees were pleased to be involved in the schemes. In Manchester, there was real enthusiasm for the scheme and optometrists felt fortunate they practised in an area that was so ‘pro-optometry’.

I think we're very lucky in the fact that we live in a community where we've got pro-optometry ophthalmologists.— GRRS

From a practice point of view … the scheme is fantastic, I think [there are] lots of advantages for patients—MECS

Positives and negatives

Both groups discussed the opportunity provided by the schemes for their practices to gain new patients. This benefit was more relevant to the MECS optometrists as most MECS patients were either referred by GPs or pharmacists.

We'd say, OK, it's your choice, generally we advise you to go back to your regular optician but that's up to you.— MECS

In GRRS, participants saw benefits in being able to offer the enhanced service to their own patients and receive payment, with the added benefit of keeping patients within their own practice.

If you have a specialist interest in glaucoma… the optoms within your own practice can refer to you. You're keeping them within your own practice, and you really do feel that you've got job satisfaction and that you're actually being paid to do a very thorough investigation.—GRRS

Neither group saw major negatives to being involved in their scheme, although in GRRS there was an issue regarding interaction with ophthalmologists at outlying hospitals. Both schemes were limited to patients resident within certain postcode areas and this was reported to be a negative feature.

Appropriateness of the case mix

The suitability of patients referred into both schemes was discussed. In GRRS, inappropriate referrals were not common but could be due to a hasty GP referral or an unaware optometrist. Relationships with optometrists outside the scheme were seen as delicate and needed careful handling. A good relationship would mean ongoing referral into their practice. A letter or telephone call tended to improve understanding of the scheme.

When I get a patient that has been referred by the wrong route… I always send a letter back to the optom explaining about the scheme and include a list of everyone [GRRS practices]. I find that [by] doing that they then refer properly.— GRRS

With MECS, inappropriate referrals were a greater issue. GPs who inappropriately referred patients made the expectations of these patients difficult to manage when they attended the optometrist. GPs from outside the participating area referring patients into the scheme was seen to be an issue. These patients take up consulting-room time for which the optometrists received no remuneration.

You don't get paid. So… on a particular day I had three people who were all outside but they were sent in by the walk-in clinic.—MECS

There was seen to be a gap in training for GPs with regard to the referral procedure.

One of the biggest downfalls of the whole scheme is that GPs are referring patients inappropriately and those patients’ expectations are not met when they get to the practice.—MECS

Communication with HES

With MECS, communication with hospitals was mixed and relied heavily on the commitment of the ophthalmologist involved in the scheme. One hospital appeared better equipped to deal with referrals; therefore, optometrists preferred to refer to this hospital.

I think if you've got someone … who wants to be referred and you say, do you want to go to hospital A or hospital B? Hospital B you'll get seen in two hours, what are you going to do?—MECS

Many of these difficulties were attributed to poor administration and knowledge of the scheme among hospital staff and ophthalmologists not directly connected to the scheme.

With GRRS, there was some concern regarding whether urgent patients received priority within the booking scheme. Although optometrists could indicate whether referral was urgent, there was scepticism whether this step would expedite referral. Some communication from the hospital to the optometrist to confirm referral receipt and appointment status was viewed as the solution to this problem. Ideally, an email or electronic referral system would be preferred.

What would be great is if you knew that an appointment at the hospital had actually been made.—GRRS

In GRRS, participants praised the communication with and feedback from the hospital, specifically from the OLGA optometrists. Optometrists always received a letter back from their GRRS referral which was not always the case with other referrals to HES.

We always get a letter back, and it's not just a letter back saying yes, but with loads of information.—GRRS

Training

Training for both schemes was viewed as valuable. GRRS participants were particularly enthusiastic, some viewed the training as the best they had ever had. Participants in both meetings found value in in-house hospital training. In MECS, it was not just clinically of value but presented an opportunity to receive oral feedback on their referrals.

Some of the best CET [Continuing Education and Training] that I've ever done.—GRRS

Especially with the ophthalmologist there because you're getting feedback as to what they think of your referrals as well.—MECS

In GRRS, it was recognised that the excellent training was given in 2013; therefore, additional formal training, perhaps annually, would be useful. The form and content of the training was discussed. Optic disc assessment was an area where all could benefit from continued training, preferably viewing stereoscopic disc images rather than monoscopic images. In a similar fashion, MECS optometrists valued peer review and saw this as a way to continue training.

Recommendations for scheme improvement

GRRS optometrists' main recommendation was for a mechanism for ensuring urgent cases were seen urgently without optometrists having to telephone to follow-up their referral. An electronic pathway with the hospital was the preferred method, allowing information to be passed in both directions, permitting optometrists to see confirmation of appointments, and providing reassurance that the referral had followed the correct route.

MECS optometrists recommended GP training and possibly some inpractice training for GP reception staff. Optometrists wished to receive ophthalmologist feedback as standard, rather than the current range between ophthalmologists who provide regular feedback and those who offer none.

With MECS, better advertising of the scheme was requested. This suggestion was regarded as the clinical commissioning group's responsibility and it was mentioned that advertising may have been held back previously to prevent overcapacity.

GPs semi-structured telephone interviews (MECS)

Impression of the scheme

GPs saw MECS as an alternative to referring patients to urgent eye clinics and offering the opportunity for a second opinion. It was viewed positively by most GPs interviewed and an improvement on care pathways for patients with eye problems.

I think it is great, especially for things like floaters [that can] be seen quickly. It is a pathway for referral and I have used it for Glaucoma referral refinement.—MECS

GP utilisation of the scheme

The number of patients referred into MECS varied considerably between optometric practices. It also depended on whether they were acute or non-acute care patients, as there was a tendency to send acute patients straight to the HES. GPs who failed to use the scheme to its full potential attributed this to lack of knowledge about the scheme and which patients were suitable for referral.

Not used as much as possible due to lack of knowledge about who they take and the pathway.—MECS

Most patients were referred into MECS from their GP practice, but there were mixed approaches to who initiated this referral. Two practices felt the decision to refer would be too much clinical responsibility for reception staff. In contrast, in one GP practice the majority of MECS patients were referred by reception staff.

Have a GP appointment first—otherwise it is too much clinical responsibility on reception staff.—MECS

Mostly referred by reception staff.—MECS

Communication

At the beginning of MECS, there were ‘teething problems’ with referral forms, and practices were only being sent cover sheets. As the scheme has progressed, these problems appear to have been rectified and GPs are happy with communication. Letters of information and referrals from MECS optometrists were appropriate and GPs found optometrists to be helpful and accommodating. GPs also commented that they received only positive feedback from MECS patients.

Only had referrals back for drops, no inappropriate referrals.—MECS

Prescribing

GPs were asked if their prescribing budget had been affected. There was a feeling that they were prescribing slightly more eye medication, but with no major impact on their prescribing budget.

Hasn't really changed. I prescribe a bit more eye gel and eye drops. Not expensive.—MECS

Recommendations

The scheme had great potential but could be improved by having more providers. GP practices had different levels of geographical coverage and a few more optometrist practices could help to keep waiting times down in busy areas.

A few more practices to refer to, to keep waiting lists down.—MECS

Better publicity of the scheme through pharmacies was recommended, and the ability of the scheme to cope with the prospect of GPs opening 7 days a week with extended hours was raised.

HES (OLGA optometrists and MECS and OLGA ophthalmologists) semi-structured telephone interviews

Impact on current practice

All hospital-based health professionals involved in both schemes viewed them as an asset to their eye care services. Any impacts on current practice were seen in a positive light, with benefits including high quality, accurate referrals with full assessment details. In MECS, the impact of patients being seen quickly, locally reducing the number of Accident and Emergency visits was seen as a major advantage. Hospital optometrists and ophthalmologists were impressed by the high quality of care the community optometrists were offering.

Receive high quality referrals with accurate information.—GRRS

I am impressed by the quality of care they are offering. They are keeping people from the hospital and patients are getting quicker responses to their problems.—MECS

Training

Training was reported to be of a high standard, but it was recognised that both schemes would benefit from ongoing training. Ophthalmologists and glaucoma specialist optometrists in the hospital stated their door was always open for optometrists to observe and refresh their skills. However, it was acknowledged that a more formal arrangement would be of benefit (eg, annual updates and training to refresh knowledge on glaucoma management and optic disc assessment training).

It would be useful for GRRS optometrists to receive yearly updates and training—GRRS

Continual CET and they need this to be mandatory.—MECS

The cost of ongoing training was raised by one GRRS ophthalmologist. Training takes place in ophthalmologists and optometrists own time, without remuneration, with a further cost implication for optometrists who have to take unpaid time out of their practice. It was felt that commissioners should recognise this issue and provide support.

Communication

In general, both schemes were viewed as easy to support, the main issues being attributable to administrative and IT difficulties. GRRS HES optometrists felt they always attempted to copy GP letters to referring optometrists, and would often address the letter to the optometrist and copy in the GP. Some MECS ophthalmologists acknowledged a reticence to copy optometrists into the GP letter. However, MECS ophthalmologists reported they were always open to communication with optometrists by telephone or email if required, and that when optometrists did contact them it was always appropriate.

I always try to give feedback on every single referral and offer open communication if they want to discuss further.—GRRS

We communicate on a weekly basis with the optometrists and ie, good [communication]. If the optometrists contact me through email or by phone it is always appropriate.—MECS

Having secure, electronic communication would benefit GRRS, and a fully electronic patient record could improve triage and communication, enabling hospitals to provide optometrists with images and information for ongoing monitoring.

Recommendations for scheme improvement

Expansion of both schemes was seen as a logical step. Most saw expansion occurring by extension to a wider area and increasing numbers of accredited optometrists, benefitting their hospital and other local hospitals. The general feeling was that if expansion occurred, they would be happy to remain involved, although one GRRS ophthalmologist had reservations if the expansion was to take on an extended role.

I would be happy with optometrists who have already established themselves on GRRS where we are confident of their skills. From a governance point of view it is quite important that if you are managing patients in the community that you see a critical mass of patients to maintain your skills.—GRRS

One MECS ophthalmologist was concerned that if the scheme expanded, then standards could fall.

Commissioners' semi-structured telephone interviews

Expectations

Two commissioners from each scheme were interviewed. Both schemes had been commissioned to reduce strain on hospitals from unwarranted referrals. All interviewed felt their schemes had met, and in some cases exceeded, expectations by successfully diverting patients from unnecessary referral, providing effective local care and allowing patients to be seen quicker and more efficiently.

Yes, it provides a secure pathway. It diverts patients away from unnecessary referral. It is very effective and it provides care more locally for patients.—GRRS

Met and exceeded [expectations] in some respects. We have seen the activity we budgeted for.—MECS

Cost-effectiveness

Commissioners for both schemes were keen to note that although there was some evidence of cost-effectiveness, the quality of care provided was a major factor. Both schemes met the QIPP (Quality, Innovation, Productivity, Prevention) criteria perfectly.9

It is not a financial service it is a quality of care, quality of service, service.—GRRS

We wouldn't have increased the budget if it wasn't. It is still early days. Quality is important too.—MECS

Communication

Both schemes had been instrumental in improving communication pathways between Commissioners and eye care professionals. Commissioners for MECS recognised that the establishment of a multidisciplinary steering group of ophthalmologists, community optometrists, GPs and commissioners had helped foster these relationships which in turn contributed to the scheme's success.

A review of the GRRS has made it much better. We now have good communication with LCS (Locally Commissioned Services) and LOC (Local Optical Committee).—GRRS

Excellent, as it began in the eye group, it came from the eye group and is supported by them. They are all very enthusiastic (consultants and optometrists) and easy to engage.—MECS

Sustainability and future expansion of the schemes

Both schemes have received continued funding and commissioners recognised scope for expansion within both schemes, although the nature of expansion was to be discussed and no commitments were made. Further evaluation of MECS was seen as vital before committing to any form of expansion.

We have two years funding which is as good as it gets. If it continues to deliver then I can see it getting mainstream funding—MECS

We are pleased with the service. While other schemes are being disbanded this one is expanding.—GRRS

Discussion

Although many studies have evaluated ESS, these have tended to focus on clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness.10–14 This is the first multi-stakeholder study to include the views of health professionals, patients and commissioners and extends the work described in the previous paper that investigated the development and implementation of the two schemes.6

The main finding is that both schemes were received positively by all involved and, despite a few minor issues and concerns, the schemes were classed as a success by commissioners, patients and providers. Patients made no negative comments on either scheme, and saw great benefit in receiving care locally.

The high quality of care provided was a theme running through all stakeholder reports. Patients, ophthalmologists and commissioners were all impressed by the standard of care, supporting the view that community optometrists are an acceptable alternative to hospital care for certain services and can provide a streamlined pathway to secondary care by eliminating unnecessary referrals.

It was acknowledged by community optometrists and HES that training was vital in producing and maintaining a high standard of care. It was widely agreed that some form of ongoing training in both schemes was required. In the current schemes, both hospital ophthalmologists and optometrists maintained an open-to-contact policy; however, in reality, community optometrists, although they knew this to be the case, felt awkward approaching and accessing the help on offer. A more structured and planned method of training could benefit all involved. How training is planned and funded would need discussion. There was an undercurrent that commissioners should recognise this requirement and provide funding for it.

This study highlights the importance of the HES being fully committed to enhanced optometric services and demonstrates the value of good interprofessional communication. In MECS, one hospital provided a more streamlined referral pathway, which led to optometrists opting to refer more urgent cases to this hospital. It is likely that referral pathways could be improved through an electronic referral system, but this would ideally require community optometrists to be connected to the N3 network, which provides secure broadband connectivity across the NHS.

Training of GPs and their staff was seen as lacking by optometrists in MECS, with knowledge of referral procedures and the correct patient pathways the main areas to address. GPs in MECS recognised this lack of knowledge and were open to further training and guidance, an area often overlooked when implementing ESS, possibly because GPs are notoriously difficult to engage due to heavy clinic loads and overstretched resources.15

The role of ESS is to streamline services, be cost-effective and reduce the burden on secondary care. Most GPs interviewed in MECS highlighted that very few patients attending the GP practice get directed to an optometrist without first being reviewed by the GP, because referral of these patients by reception staff conferred too much clinical responsibility. Some patients who required particular eye-drops were referred back from the MECS optometrist to the GP for prescribing, resulting in a three visit consultation, which is neither cost-effective nor streamlined. Although MECS optometrists were able to supply a number of ophthalmic medications that are appropriate for treating common eye conditions, for example, ocular lubricants, topical antibiotics and antiallergy drugs, none of the participating optometrists had specialist prescribing qualifications.16 Consequently, some patients were referred back to the GP for them to prescribe certain medications that the optometrist was unable to supply or where it was likely that the patient needed repeat prescribing for a chronic condition, for example, preservative-free lubricants for dry eye. In future, this problem could potentially be addressed via the use of Patient Group Directions (PGDs), which provide a legal framework that allows particular healthcare professionals (including optometrists) to supply and/or administer a specified medicine(s) to a predefined group of patients, without them having to see a doctor.

The local nature of both schemes raises issues of equity of care. GRRS could be expanded, through recruitment of more optometrists and practices to cover a wider area. However, wide expansion would not be possible with MECS as bordering areas, such as Croydon, have their own schemes and cross-funding is an issue. Commissioners are aware that optometrists favour a scheme across South London, but some commissioners appear reluctant to fund this enlarged scheme. Government changes and healthcare priorities put ESS under pressure to perform and continually prove their effectiveness. If either scheme were to be expanded, careful consideration would need to be taken to ensure quality of care is maintained. Structured training, and clear patient pathways would need to be put in place.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The major strength of this study is the multi-stakeholder perspective. The mixed methods approach to capturing these views offered each group a convenient and congenial opportunity to voice their opinions. There was an excellent response rate for participants heavily invested in the scheme (optometrists, HES and commissioners).

There are some study limitations. All participation was voluntary and though every attempt was made to maximise the number of participants, some groups are represented more than others. GPs in MECS were particularly difficult to recruit and those recruited could have been the ones with more positive views of the scheme. Data saturation is often used as a quality indicator in qualitative research. Resource limitations and participant availability meant that we were only able to conduct two optometrist focus groups. To ensure that the views and experiences of the majority of scheme participants were captured, these groups were larger than is optimal and it is possible that further themes may have emerged by using multiple smaller groups. However, the optometrist focus groups were characterised by a high level of participant engagement and consensus was reached. We are therefore confident that we have reliably identified the views of participating community optometrists regarding both schemes.

Conclusions

This multi-stakeholder study identified that locally commissioned ESS can be a positive experience for all involved. With appropriate training, clear referral pathways and good communication, community optometrists can offer high-quality services that are highly acceptable to patients, health professionals and commissioners.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for giving up their time to participate in the study. The authors would also like to thank members of the Enhanced Scheme Evaluation Project Steering Group for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: The analysis and interpretation of the data was initially undertaken by HB and checked by JGL, RAH and DFE. The article was drafted by HB and revised by JGL, RAH and DFE. All authors contributed to the design of the study and approved the final version of the article. HB is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant from the College of Optometrists.

Competing interests: HB's time on this study was funded by the College of Optometrists.

Ethics approval: School of Health Sciences Research and Ethics Committee, City, University of London.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Department of Health. General Ophthalmic Services Review. Findings in relation to the framework for primary ophthalmic services, the position of dispensing opticians in relation to the NHS, Local Optical Committees, and the administration of General Ophthalmic Services payments. Gateway reference: 7689 2007. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_063984 (accessed 17 Oct 2016).

- 2.Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD et al. Why we don't come: patient perceptions on no-shows. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:541–5. 10.1370/afm.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owsley C, McGwin G, Scilley K et al. Perceived barriers to care and attitudes about vision and eye care: focus groups with older African Americans and eye care providers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:2797–802. 10.1167/iovs.06-0107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laine C, Davidoff F, Lewis CE et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients’ and physicians’ opinions. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:640–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S. Difference between ophthalmologists’ and patients’ perceptions of quality of life associated with age-related macular degeneration. Can J Ophthalmol 2000;35:127–33. 10.1016/S0008-4182(00)80005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konstantakopoulou E, Harper RA, Edgar DF et al. A qualitative study of stakeholder views regarding participation in locally commissioned enhanced optometric services. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004781 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.https://gp-patient.co.uk/surveys-and-reports (accessed Nov 2015).

- 8.Ritchie J. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG eds. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The NHS quality, innovation, productivity and prevention challenge: an introduction for clinicians, Department of Health gateway reference: 13551 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_113806 (accessed 17 Oct 2016).

- 10.Park JC, Ross AH, Tole DM et al. Evaluation of a new cataract surgery referral pathway. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:309–13. 10.1038/sj.eye.6703075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns DH, Dart JK, Edgar DF. Review of the Camden and Islington anterior segment eye disease scheme. Optom Pract 2002;3:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheen NJ, Fone D, Phillips CJ et al. Novel optometrist-led all Wales primary eye-care services: evaluation of a prospective case series. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:435–8. 10.1136/bjo.2008.144329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parkins DJ, Edgar DF. Comparison of the effectiveness of two enhanced glaucoma referral schemes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2011;31:343–52. 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratnarajan G, Newsom W, Vernon SA et al. The effectiveness of schemes that refine referrals between primary and secondary care—the UK experience with glaucoma referrals: the Health Innovation & Education Cluster (HIEC) Glaucoma Pathways Project. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002715 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller R, Peckham S, Coleman A et al. What happens when GPs engage in commissioning? Two decades of experience in the English NHS. J Health Serv Res Policy 2016;21:126–33. 10.1177/1355819615594825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/CPD/Therapeutics/index.cfm (accessed Nov 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011934supp1.pdf (138.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-011934supp2.pdf (196.8KB, pdf)