Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate if a referral intervention improves the patient experience of the referral and treatment process.

Setting

Interface between 14 primary care surgeries and a district general hospital.

Participants

The 14 general practitioner (GP) surgeries (7 intervention, 7 control) in the area around the University Hospital of North Norway Harstad were randomised and all completed the study. Consecutive individual patients were recruited at their hospital appointment. A total of 500 patients were recruited with 281 in the intervention and 219 in the control arm.

Interventions

Dissemination of referral templates for 4 diagnostic groups (dyspepsia, suspected colorectal cancer, chest pain and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) coupled with intermittent surgery visits by study personnel. The control arm continued standard referral practice. The intervention was in use for 2.5 years.

Outcome

The main outcome was a quality indicator score. This paper reports a secondary outcome, the patient experience, as measured by self-report questionnaires. GPs in the intervention group could not be blinded. Patients were blinded to intervention status. Analysis was based on single-question comparison with a questionnaire subscore used to assess the effect of clustering.

Results

On the individual questions, overall satisfaction was very high with minor differences between the intervention and control group. Interestingly, the most negative responses, in both groups concerned questions relating to patient interaction and information. Very little evidence of clustering was found with an estimated intracluster correlations coefficient at 1.21e−11.

Conclusions

In total, this indicates no clear effect of the implementation of referral templates on the patient experience, in a setting of generally high patient satisfaction.

Trial registration number

NCT01470963; Results.

Keywords: Patient experience, Referral, General practitioner

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Clinically relevant research in a regular district hospital setting.

High response rate.

Newly developed questionnaire hampers wider generalisation.

Introduction

Evaluation of patient experience and satisfaction is widespread with a wealth of literature concerning the development and use of questionnaires.1–5 The evaluation of patient experience can help drive quality improvement,6 and improved patient experience is associated with safety and clinical effectiveness.7

Care coordination is an important aspect of a well-functioning high-quality health service. It has been defined as ‘the deliberate integration of patient care activities between two or more participants involved in a patient's care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services’.8 In the USA, the National Quality Forum (NQF) has published preferred practices for care coordination, including transitions of care.9 This report includes clear recommendations for participation of the patient, or his/her designee, in the decision, planning and execution of a care transition. This is important, as exemplified by a recent Australian article, where patients with colorectal cancer perceived that poor information exchange led to suboptimal care.10 Hence assessing patient experience of the referral process may be beneficial in assessing the effect of a referral intervention.

This article presents the patient experience aspect of a cluster randomised study evaluating the effect of the implementation of referral templates for four diagnostic groups—dyspepsia, suspected colorectal cancer, chest pain and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—in the patient referral pathway.11 Previously, we have shown that the referral templates led to increased referral quality,12 and the effect on the main outcome, quality of care at the hospital, is in publication. This publication aims to assess whether the implementation of a referral template in the transition of care from the general practitioner (GP) to the hospital has affected the patient experience of the care process.

Methods

Study setting

In Norway, the healthcare system is quite uniformly organised throughout the country. GPs act as gatekeepers to secondary care,13 with specialist health services delivered by governmentally owned regional health authorities, mainly through public hospitals. Some specialist outpatient care is delivered by private specialists, but this is mainly purchased by the regional health authorities. The access to private specialists in the geographical area of the current study is very limited.

Study design

The study was designed as a cluster randomised study with the GP surgery as the clustering unit. A total of 14 surgeries were randomised, 7 to the intervention and 7 to the control group. The clustered design was chosen to avoid possible spill-over effect from the intervention to control GPs. Randomisation was performed by simple drawing by a person not connected to the research team, stratified by town versus countryside location of surgery.

As the intervention was to be actively used by the GPs, the referring GP could not be blinded. Patients, hospital doctors and outcome evaluators were blinded to the intervention status of the patients. Owing to the design of the intervention, the referral letter would sometimes reveal the intervention status, if the electronic template was used. No separate sample size calculation was performed for the patient experience outcome. The full study details are published in the methods paper.11

Intervention

The intervention consisted of the distribution of four separate referral templates to the intervention surgeries. These templates covered four clinical areas (dyspepsia, suspected colorectal malignancy, chest pain and COPD). The templates were to be used when initiating a new referral to the medical outpatient clinic at the University Hospital of North Norway, Harstad (UNN Harstad). The templates were distributed by the corresponding author (HW) during educational and/or lunch meetings and were provided as laminated reference sheets or in electronic form. In addition, follow-up visits were conducted regularly during the study period and intermittent mail leaflets and reminders were distributed to the intervention surgeries. Control offices continued standard referral practice.

Outcomes

The main outcome in the project was the quality of care delivered to each individual patient. In addition, health process indicators such as correct prioritisation were recorded and referral quality was also compared between the intervention and control group. The current paper presents the patient experience aspect of the study, as measured by self-report questionnaires.

Participants

The 14 GP surgeries primarily served by UNN Harstad were included in the randomisation process. In 2013, these surgeries had a total list size of 39 523 patients. The individual patients were recruited from consecutive new patients within one of the four clinical areas referred to, at the medical outpatient clinics at UNN Harstad. Study information and a consent form were sent to each individual patient together with their appointment letter. Further information, including a new consent form if appropriate, was provided at their hospital appointment. The individual patients were analysed as part of the intervention or control group depending on the intervention status of the GP surgery they were referred from. Children (<18 years of age) and patients with reduced capacity to consent were excluded from the study.

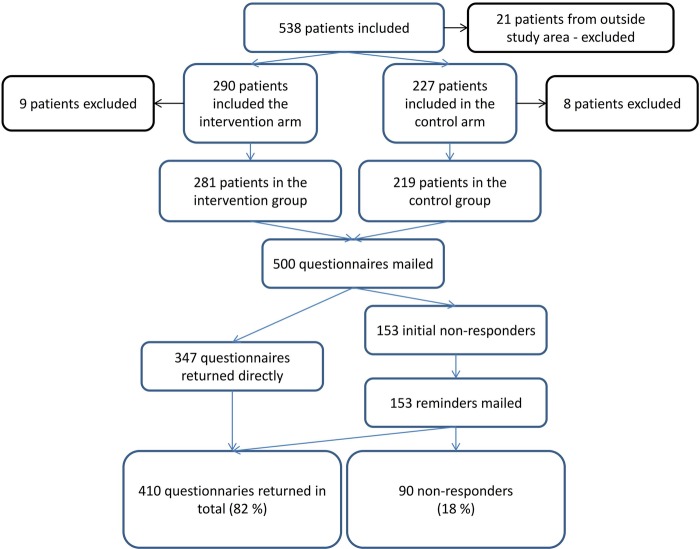

Recruitment

The study recruited patients for ∼2.5 years and a total of 538 patients were included with 290 in the intervention arm and 227 in the control arm. The remaining 21 patients were referred from GP surgeries outside the regular area of UNN Harstad, and as such neither in the intervention nor the control group. These 21 were excluded, together with 17 patients who did not fill the inclusion criteria. In total, this left 281 patients in the intervention arm and 219 patients in the control arm (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion and questionnaire response.

Questionnaire development

Multiple tools exist for measuring different aspects of care coordination14 and patient experience; however, no complete questionnaire was located that covered the area in the current study completely. Therefore, a questionnaire was developed by combining validated questionnaires regarding patient experiences and care coordination. The questions used were the full version of the Generic Short Patient Experiences Questionnaire (GS-PEQ),15 together with two further questions used in patient experience questionnaires in the Norwegian healthcare system (questions 11 and 12)16 and the two questions about health interaction from the Commonwealth Fund Survey 2010.17 Three further questions were added to assess (1) who referred the patient, (2) if the referral was seen as appropriate and (3) an overall evaluation of the institution. Table 1 presents the questions in the questionnaire. GS-PEQ and questions 11–12 use Likert-style response categories. The health interaction questions had a yes/no response. The full questionnaire, including the demographic questions, is available on request.

Table 1.

Questionnaire details

| Question no. | Wording of question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Did the clinicians* talk to you in a way that was easy to understand? |

| 2 | Do you have confidence in the clinicians' professional skills? |

| 3 | Did you get sufficient information about how examinations and tests were to be performed? |

| 4 | Did you get sufficient information about your diagnosis/conditions? |

| 5 | Did you perceive the treatment to be adapted to your situation? |

| 6 | Were you involved in decisions regarding your treatment? |

| 7 | Did you perceive the institution work practices to be well organised? |

| 8 | Did you perceive the equipment at the institution to be in good working order? |

| 9 | Overall, was the help and treatment you received at the institution satisfactory? |

| 10 | Do you believe that you were in any way given incorrect treatment (according to your own judgement)? |

| 11 | Did you have to wait before you were given an appointment at the institution? |

| 12 | Overall, what benefit have you had from the care at the institution? |

| 13 | Did the hospital specialist lack basic medical information from your GP about the reason for your visit or test results? |

| 14 | After you saw the hospital specialist, did your GP lack important information about the care you got from the specialist? |

| 15 | Was the referral to the outpatient department necessary (according to your own judgement)? |

| 16a | Were you referred by your GP for the outpatient appointment? |

| 16b | If no in question 16a; who referred you? |

| 17 | If you take an overview of your entire treatment process, how would you evaluate the institution? |

*With ‘clinicians’, we mean those who had the main treatment responsibility. This is linguistically clearer in the Norwegian wording.

The questionnaire was piloted for content validity with four local health professionals; these felt that it covered the important aspects of patient experience and care coordination. It was then piloted with five outpatients with a median age of 72 years (average 68.8 years) to ensure face validity and acceptability. Two patients needed clarification on one of the questions before they felt they could answer, and the wording of this question was adjusted accordingly. The patients felt the questionnaire was acceptable, with logical response categories and that the questions covered their clinical path during the referral process well. These patients did not take part when the project was later initiated. No further formal evaluation of the questionnaire was carried out.

Questionnaire distribution

The questionnaire was mailed to patients who had consented to take part in the referral project presented above. To increase response rates, a prepaid response envelope was included, addresses were handwritten, the questionnaire was kept short and association with research bodies was indicated.3 For non-responders, one reminder was sent ∼1 month after the first questionnaire, with a new questionnaire and prepaid response envelope.

Ethics

The study followed the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Before recruitment started, it was presented to the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics Northern Norway, who determined it not to be within the scope of the Health Research Act (REK NORD 2010/2259). The project has been approved by the Data Protection Officer for Research. The study is registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, with trial registration number NCT01470963. All patients provided written informed consent.

Imputation

To further aid the assessment of clustering, missing data were imputed. For the imputation, answers set as ‘not applicable’ were counted as missing. Missing data were seen to be random and multiple imputation using chained equations was employed. This has been shown to perform well for a variety of variable scaling types.18 Every variable used in further statistical analysis was entered into the imputation model, as failure to do so may bias estimates towards the null.19 The ordinal response scales for each single question were to be combined into a continuous score, and as such, it was determined that imputation with predictive mean matching was appropriate. As shown by van Buuren,19 the number of iterations can usually be quite low, between 5 and 20. In this study, the Stata standard of 10 iterations as burn-in period was used.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented on single question basis with comparison between the two groups using the Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal data and χ2 test for nominal data. No correction for clustering was made as the estimated ICC was very low (shown below). Aggregation of scores was postulated in the methods paper,11 but discarded as a main outcome as properties of the questionnaire, with a ‘not applicable’ answering category, are not easily suitable for such an approach. However, to assess the effect of clustering, a sum of scores from the GS-PEQ part of the questionnaire was calculated and a multilevel regression model was built with the GS-PEQ score from the questionnaire as the dependent variable. Intervention status was included in the model as this is the main point of interest. Gender, age, education level and self-perceived health were included in the model, as these tend to influence patient experience.20–22 Age was centred to ease interpretation in a mixed model analysis.23 Self-perceived health was reported on a five-level Likert-style scale and education level in four categories. Both were included as dummy variables in the analysis. Other confounding variables were assessed in the model and included if their inclusion led to a >10% change in the main outcome when added to the base model (main outcome+intervention status). Relevant interactions were checked for relevant variables, where p<0.10 was set as the significance level. As imputation was used, Monte Carlo error estimates were employed to assess the level of simulation error, as suggested by White et al.24 Normal evaluation of multilevel models with loglikelihood ratio tests were not carried out, as this is not well defined for multilevel models with imputed data. The analysis employed restricted maximum likelihood techniques throughout, as suggested when the number of clusters is small.25 As described, multiple imputation was used to account for missing data in the multilevel regression model assessing the effect of clustering. Stata V.13.1 (StataCorp 2013, Texas, USA) were used for all analysis.

Results

Response rate

The response rate was 69.4% before reminders were sent out, rising to 82.0% after reminders (figure 1). The mean age for responders was 61 years and for non-responders 47 years (t-test <0.0001). There was no significant gender difference between the responders and non-responders, and the response rate did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group (χ2 test).

Missing data

Missing data for most questions were low, ranging from 0 to 11 out of 410 answered questionnaires. Statistically, these were considered missing completely at random (MCAR) with no clear relation to either age, gender, self-perceived health, disease severity or other variables.26 However, questions 6, 10 and 12 in the general part of the questionnaire had higher amounts of not applicable ranging from 14 to 34 representing 3.4–8.3% of returned questionnaires. In these questions, the word ‘treatment’ was used. This was intended to cover the medical examination and interventions during the outpatient visit. However, it seems that this has been misunderstood by several patients. It seems reasonable to assume that patients who underwent ‘only’ diagnostic evaluation felt that they had received no ‘treatment’, and hence felt unable to answer the question. This was also highlighted by one patient in a free-text response in the questionnaire. ‘Not applicable’ to questions 6, 10 and 12 did not vary significantly with age (t-test), intervention group status (χ2 test), gender (χ2 test) or self-reported health (χ2 test). This was treated as missing at random for imputation purposes (MAR).26 Question 14 had a missing rate of 15.9% but also yielded a high level of not applicable responses, at 46.0% of returned questionnaires. This was expected, as many people will not have had a new appointment with their GP following the hospital outpatient evaluation. It is also reasonable to assume that the high amount of missing was related to the same concept. The response ‘not applicable’ did not significantly vary with age (t-test p=0.868), intervention group status (χ2 test p=0.064) or self-reported health (χ2 test p=0.459).

A histogram of responses to questions with five categories showed all response sets to be skewed to the left. However, earlier work has indicated that multiple imputation can perform well, even when the categorical variable is non-normally distributed, as long as MAR does not exceed 10%.27 In a 2010 article, Finch26 argues that multiple imputation performs well for imputation of missing categorical questionnaire data. There was no association between levels of missing data and the multilevel structure of the data.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in table 2. There was no major difference between the intervention and control group with regard to gender, age, urban or rural residency or questionnaire response. The effect of the referral intervention on referral quality has previously been shown to be clinically significant with an effect of 18% (95% CI 11 to 25, p<0.001).12 However, this was for the full data set of 500 patients. To ensure that this was also representative of the subpopulation who answered the questionnaire, the multilevel regression model was employed using data from only the 410 patients who answered it. This showed an intervention effect of 19% (95% CI 12 to 27, p<0.001) on referral quality, well within the 95% CI of the full analysis.

Table 2.

Selected patient baseline characteristics by intervention status

| Intervention group | Control group | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female/male, N (%) | 140 (59.3)/96 (40.7) | 102 (58.6)/72 (41.4) | 0.89 |

| Age (year), mean (±SD) | 60.9±12.5 | 60.3±13.5 | 0.63 |

| Urban/rural, N (%) | 145 (61.4)/91 (38.6) | 95 (54.6)/79 (45.4) | 0.17 |

| Clinical group, N (%) | |||

| Dyspepsia | 117 (49.6) | 96 (55.2) | 0.29 |

| Suspected colorectal malignancy | 75 (31.8) | 57 (32.8) | |

| Chest pain | 40 (17.0) | 18 (10.3) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Hospital appointment with senior house officer/specialist, N (%) | 107 (45.3)/129 (54.7) | 78 (44.8)/96 (55.2) | 0.92 |

| Questionnaire returned promptly/after mailed reminder, N (%) | 202 (85.6)/34 (14.4) | 145 (83.3)/29 (16.7) | 0.53 |

Questionnaire results

Overall satisfaction with services was high and as presented in table 3, there was little difference between the intervention and control group for the individual questions. Using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test and Fisher exact test, only two questions had significant p values (Q14 and Q17); however, in these questions, the absolute difference in numbers was very small. All response sets were skewed to the left, that is, towards more positive responses.

Table 3.

Questionnaire results

| Question | Answering categories* | Intervention | Control | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1† | 5 (4, 5) | 5 (4, 5) | 0.92 | |

| Question 2† | 5 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 0.39 | |

| Question 3† | 5 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 0.23 | |

| Question 4† | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (4, 4) | 0.12 | |

| Question 5† | 4 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 0.88 | |

| Question 6† | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 4) | 0.19 | |

| Question 7† | 4 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 0.22 | |

| Question 8† | 4 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 0.81 | |

| Question 9† | 5 (4, 5) | 4 (4, 5) | 0.15 | |

| Question 10† | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (5, 5) | 0.60 | |

| Question 11‡ | No | 33 (14.0) | 21 (12.1) | 0.33 |

| Yes, but not too long | 155 (66.0) | 111 (64.2) | ||

| Yes, quite long | 34 (14.5) | 29 (16.8) | ||

| Yes, too long | 13 (5.5) | 12 (6.9) | ||

| Question 12‡ | No benefit | 3 (1.4) | 5 (3.1) | 0.56 |

| Little benefit | 12 (5.5) | 7 (4.3) | ||

| Some benefit | 59 (27.2) | 44 (27.0) | ||

| Large benefit | 106 (48.9) | 86 (52.8) | ||

| Very large benefit | 37 (17.1) | 21 (12.9) | ||

| Question 13‡ | Yes | 4 (1.7) | 6 (3.5) | 0.25 |

| No | 229 (98.3) | 165 (96.5) | ||

| Question 14‡ | Yes | 4 (4.2) | 8 (13.1) | 0.04 |

| No | 92 (95.8) | 53 (86.9) | ||

| Question 15‡ | Yes | 232 (99.2) | 170 (99.4) | 0.75 |

| No | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Question 17‡ | Much poorer than expected | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.03 |

| Somewhat poorer than expected | 0 (0) | 5 (3.1) | ||

| As expected | 119 (54.1) | 94 (58.4) | ||

| Somewhat better than expected | 50 (22.7) | 32 (19.9) | ||

| Much better than expected | 51 (23.2) | 29 (18.0) |

*For questions 1–10, the following scoring was used: 1, not at all; 2, to a small extent; 3, to some extent; 4, to a large extent and 5, to a very large extent.

†Data presented as median (25th centile, 75th centile).

‡Data presented as number (%).

Interestingly, the highest numbers of scores indicating dissatisfaction were for questions 4 and 6, for the intervention and control group patients. These questions concern patient interaction and information on the treatment process.

The Cronbach α for questions 1–15 was 0.83 and for questions 1–10 0.88.

Assessment of clustering effect

In the regression model, no significant difference was seen in the GSPEQ score between the intervention and control group with the regression coefficient 0.55 (95% CI −0.37 to 1.47, p=0.24) when taking clustering into account and adjusted for confounding variables 0.57 (95% CI −0.31 to 1.46, p=0.20). No significant interaction was found, and the result was not confounded by GP specialist status, GP gender, specialist status of hospital doctor or seriousness of final diagnosis. The Monte Carlo error estimates were within the limits recommended.24 Initial multilevel analysis of the data revealed virtually no variance of the intercepts. The ICC was estimated at 1.21e−11. Hence, very little of the variation in the data was related to the clustered design.

Discussion

In the presentation of the data from each question in table 3, it is quite clear that, for the most part, patients in this project report positive experiences, with no differences between the intervention and control group. It hence seems that although the intervention has increased the referral quality significantly,12 this has not translated into a more positive patient experience with the referral process and treatment, as measured by self-report questionnaires. In the current study, indepth data analysis with imputation and multilevel regression modelling was employed to further explore the effect of clustering. No clear effect of clustering was found.

A strength of the current study is the fairly high response rate (82.0%) compared with other mail response studies.28 However, the potential for non-response bias is always present. Others have previously shown the effect of this to be small.29 30 Earlier Norwegian studies have suggested only minor differences between answers provided by responders and non-responders, when the latter have been obtained through telephone follow-up interviews.31–33 A clear limitation is the use of short-form questionnaires with single items, which may be less valid than longer forms.34 However, shorter forms will increase the response rate.4 35 The current project aimed to assess the effect of a health system intervention and the patient experiences with care after this intervention. We hence decided to keep the questionnaire short to enable a high response rate and keep the patient and staff workload manageable.

The current project used a newly developed questionnaire to assess patient experience by combining previously validated questions. The general nature of the final questionnaire may be seen as a weakness, as small changes in the patient experience induced by the intervention may have been missed. Further piloting might have revealed more clearly if the questionnaire did indeed assess the patient experience with the referral and care process in an adequate way. However, in this clinically oriented project, the authors hoped that a more general questionnaire would highlight whether the intervention would cause a more overall positive, or even a negative, change. It is probable that for each individual patient, it is the experience with the entire process that matters, as opposed to the experience of a subpart of the process. If large-scale implementation of referral guidance is contemplated, a more specific questionnaire may need to be validated.

An additional weakness was the lack of a sound analytical plan proposed in the methods paper.11 To ensure transparency, the analysis presented in this paper is therefore simple and based on single-question assessment. Given the clustered nature of the study, an assessment of clustering is given for a subsection of the questionnaire, but very little effect was seen.

Comparison with other studies was difficult as no clearly comparable analysis was found, except for the two health interaction questions. In the current study, 1.7% in the intervention group and 3.5% in the control group felt the hospital specialist lacked information from the GP. About 4.2% in the intervention and 13.1% in the control group felt the GP lacked information from the specialist. In the Norwegian part of the 2010 Commonwealth Fund Survey, the same questions gave much higher negative ratings, with 12.1% indicating that the specialist lacked information from the GP and 38.3% indicating that the GP lacked information from the hospital.17 Data from the 2013 Commonwealth Fund Survey suggest similar ratings as in 2010, although the wording of the questions is slightly different.36 A Norwegian report concerning patient experience as inpatients also suggests higher dissatisfaction with co-operation between the hospital and the GP37 than in the current study. In total, this clearly suggests that the patient experience of the GP/specialist communication is better in a small district hospital than the country average suggests. It is therefore possible that the effect of the intervention on patient experience could have been higher if the level of dissatisfaction with the healthcare cooperation had been higher in the local population. However, this also may suggest that although the hospital consultants often feel information is lacking in the referrals,38 39 this is not necessarily experienced as a problem by patients.

In the current study, two questions were answered more negatively than others. These questions therefore probably provide the most interesting points for further quality improvement at the local facility. These two questions represent areas where communication is the main concept, namely patient involvement in the treatment process and information from doctors to patients. Others have previously shown communication and information errors as a cause for dissatisfaction,40 and in other jurisdictions even malpractice claims.41 42

Conclusion

In this project, patient satisfaction, as measured by patient experience questionnaires, was generally high, with no major differences between the intervention and control group. No clear effect of the implementation of referral templates on patient satisfaction was evident.

Interestingly, the most negative feedback, from the intervention and control group, was concerning patient interaction, involvement and information. Effective communication and involving patients in decision-making may help to increase patient satisfaction to an even higher level.

Footnotes

Contributors: The administration and daily running of the study was performed by HW, who was also the grant holder. ARB and HW developed the questionnaire. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors revised drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was funded by a research grant from the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Nord RHF) with grant number HST1026-11.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The project has been approved by the Data Protection Officer for Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess 2002;6:1–244. 10.3310/hta6320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrat A, Solheim E, Danielsen K. National and cross-national surveys of patient experiences: a structured review. July 2008 Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:MR000008 10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards P. Questionnaires in clinical trials: guidelines for optimal design and administration. Trials 2010;11:2 10.1186/1745-6215-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton M et al. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials: a review. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellins J. Great expectations? Reflections on the future of patient and public involvement in the NHS. Clin Med 2011;11:544–7. 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-6-544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e001570 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald K, Sundaram V, Bravata D et al. Closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Quality Forum. Preferred practices and performance measures for measuring and reporting care coordination: a consensus report Washington, DC: National Quality Forum, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascoe SW, Veitch C, Crossland LJ et al. Patients’ experiences of referral for colorectal cancer. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:124 10.1186/1471-2296-14-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wåhlberg H, Valle PC, Malm S et al. Practical health co-operation—the impact of a referral template on quality of care and health care co-operation: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:7 10.1186/1745-6215-14-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wåhlberg H, Valle PC, Malm S et al. Impact of referral templates on the quality of referrals from primary to secondary care: a cluster randomised trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:353 10.1186/s12913-015-1017-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsen B, Norheim OF. Introduction of the patient-list system in general practice. Changes in Norwegian physicians’ perception of their gatekeeper role. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:209–13. 10.1080/02813430310004155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J et al. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:119 10.1186/1472-6963-13-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjetne IS, Bjertnaes OA, Olsen RV et al. The Generic Short Patient Experiences Questionnaire (GS-PEQ): identification of core items from a survey in Norway. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:88 10.1186/1472-6963-11-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjetne IS, Bjertnes OA, Iversen HH et al. Pasienterfaringer i spesialisthelsetjenesten. Et generisk, kort spørreskjema. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skudal KE, Bjertnes OA, Holmboe O et al. The 2010 Commonwealth Fund survey: results from a comparative population survey in 11 countries. 21 Oslo: The Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KJ, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:624–32. 10.1093/aje/kwp425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:219–42. 10.1177/0962280206074463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao H, Barber JP. The effect of perceived health status on patient satisfaction. Value Health 2008;11:719–25. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzpatrick R. Surveys of patient satisfaction: II—designing a questionnaire and conducting a survey. BMJ 1991;302:1129–32. 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Da Costa D, Clarke AE, Dobkin PL et al. The relationship between health status, social support and satisfaction with medical care among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Qual Health Care 1999;11:201–7. 10.1093/intqhc/11.3.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twisk J. Applied multilevel analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011;30:377–99. 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eldridge S, Kerry S. A practical guide to cluster randomised trials in health services research. 1st edn Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finch W. Imputation methods for missing categorical questionnaire data: a comparison of approaches. J Data Sci 2010;8:361–78. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leite W, Beretvas S. The performance of multiple imputation for Likert-type items with missing data. J Mod Appl Stat Methods 2010;9:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitzia J, Wood N. Response rate in patient satisfaction research: an analysis of 210 published studies. Int J Qual Health Care 1998;10:311–17. 10.1093/intqhc/10.4.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasek RJ, Barkley W, Harper DL et al. An Evaluation of the impact of nonresponse bias on patient satisfaction surveys. Med Care 1997;35:646–52. 10.1097/00005650-199706000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perneger TV, Chamot E, Bovier PA. Nonresponse bias in a survey of patient perceptions of hospital care. Med Care 2005;43:374–80. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156856.36901.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guldvog B, Hofoss D, Pettersen KI et al. PS-RESKVA—pasienttilfredshet i sykehus [PS-RESKVA—patient satisfaction in hospitals]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1998;118:386–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Do non-respondents’ characteristics and experiences differ from those of respondents? Poster at the 25th International Conference by the Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua). 25th International Conference by the Society for Quality in Healthcare (ISQua); 08 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Using telephone interviews to explore potential non-response bias in a national postal survey. Poster at the 26th International Conference by the Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua). 26th International Conference by the Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua); 09 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eaker S, Bergström R, Bergström A et al. Response rate to mailed epidemiologic questionnaires: a population-based randomized trial of variations in design and mailing routines. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:74–82. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haugum M, Bjertnes OA, Iversen HH et al. Commonwealth Fund's health policy survey in 11 countries: Norwegian results in 2013 and development since 2010. 27 November 2014 Oslo: The Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skudal KE, Holmboe O, Iversen HH et al. Inpatients’ experience with Norwegian hospitals: national results in 2011 and changes from 2006. March 2012 Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canadian Medical Association. National survey: experiences with referrals from primary to specialty care. Canadian Medical Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodek S, Ghori K, Edelstein M et al. Contemporary referral of patients from community care to cardiology lack diagnostic and clinical detail. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:595–601. 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00902.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiidenhovi H, Nojonen K, Laippala P. Measurement of outpatients’ views of service quality in a Finnish university hospital. J Adv Nurs 2002;38:59–67. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP et al. Physician–patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA 1997;277:553–9. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540310051034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL et al. The doctor–patient relationship and malpractice. Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1365–70. 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420120093010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]