Abstract

We present the first speleothem-derived central North Africa rainfall record for the last glacial period. The record reveals three main wet periods at 65-61 ka, 52.5-50.5 ka and 37.5-33 ka that lead obliquity maxima and precession minima. We find additional minor wet episodes that are synchronous with Greenland interstadials. Our results demonstrate that sub-tropical hydrology is forced by both orbital cyclicity and North Atlantic moisture sources. The record shows that after the end of a Saharan wet phase around 70 ka ago, North Africa continued to intermittently receive substantially more rainfall than today, resulting in favourable environmental conditions for modern human expansion. The encounter and subsequent mixture of Neanderthals and modern humans – which, on genetic evidence, is considered to have occurred between 60 and 50 ka – occurred synchronously with the wet phase between 52.5 and 50.5 ka. Based on genetic evidence the dispersal of modern humans into Eurasia started less than 55 ka ago. This may have been initiated by dry conditions that prevailed in North Africa after 50.5 ka. The timing of a migration reversal of modern humans from Eurasia into North Africa is suggested to be coincident with the wet period between 37.5 and 33 ka.

The North African region experienced dramatic changes in climatic and hydrological conditions during the Pleistocene1 with important consequences for human evolution and dispersal. The region lies at a critical boundary position between polar and subtropical air masses and its climate is influenced by both the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. However, the specific mechanisms behind these influences and resulting hydrological changes are not well understood. Marine records of dust and runoff2,3 as well as Holocene terrestrial records4,5, point to the over-riding importance of the precession cycle in controlling North African rainfall6. On the other hand, there is a lack of terrestrial evidence for past precipitation, particularly for the pre-Holocene for which well-dated time series are almost absent.

Speleothems, especially stalagmites, are well established terrestrial archives of past environmental and climate conditions through time series of proxies including δ18O, δ13C and trace element concentrations7. Under specific circumstances, speleothem formation itself represents a direct proxy for hydrological changes at sites where water availability was highly variable in the past. For example, the very presence of speleothems in caves located in currently arid areas indicates dramatic changes in water availability and epikarst recharge8,9. We present a palaeohydrological record based on a stalagmite from Susah Cave (Fig. 1, 32°53.419′N, 21°52.485′E), a shallow cave positioned at ~200 m altitude on the northern flank of Jebel Malh in the Al Akhdar Massif in Cyrenaica, Libya, in close proximity to Haua Fteah, an archaeological cave site with evidence for human occupation since about 75 ka10,11. Today, the region experiences average precipitation of less than 200 mm per year, with most rainfall between October and April, sustaining a Mediterranean ‘Maquis’ vegetation with a thin soil cover. Reflecting this low rainfall, Susah Cave is hydrologically inactive today, with no evidence of water flow or dripping anywhere in the cave. Speleothem formations are covered with dust, and the majority of the specimens are broken. The sample used here (SC-06-01) is a 93 cm-long stalagmite that was found broken, but the basal piece fitted onto its stump so that completeness of the specimen could be demonstrated (Supplementary Information (SI), Fig. S2). Thin red layers similar to the superficial dust coating separate individual growth intervals, and mark episodic dry phases or events with concomitant dust deposition inside the cave. The chronology and derived age model are based on 116 reliable and precise U-Th dates12 along the growth axis (SI, Table S1). For palaeoclimatic analyses, stable oxygen and carbon isotopes (δ18O and δ13C) were measured along the growth axis at 1 mm resolution or, for sections with slow growth, at 0.15 mm.

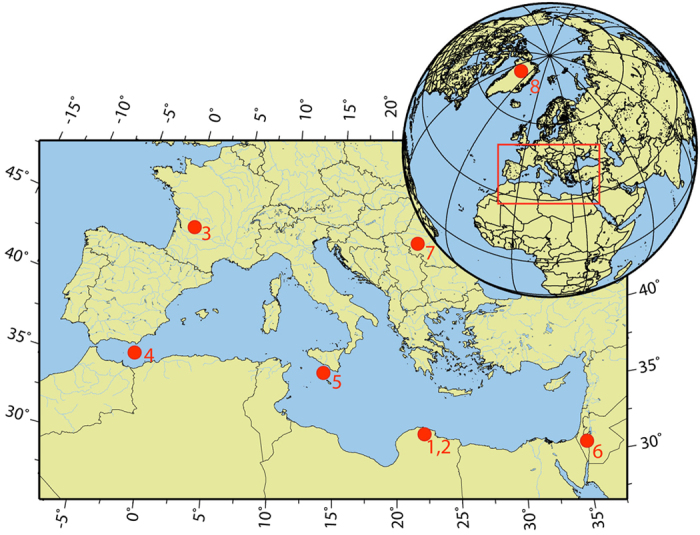

Figure 1. Map showing the locations of 1, 2) Susah Cave in northern Libya and nearby site Haua Fteah11, 3) Villars Cave21 in France, 4) marine sediment core ODP 97728, 5) marine sediment core ODP 96327, 6) Levant with archaeological sites Kebara44 and Boker Tachit39, 7) Peştera cu Oase48 and 8) NGRIP ice core24.

. The map was created using the Geomar GMT-Maps web site (http://sfb574.geomar.de/gmt-maps.html).

Growth phases and insolation

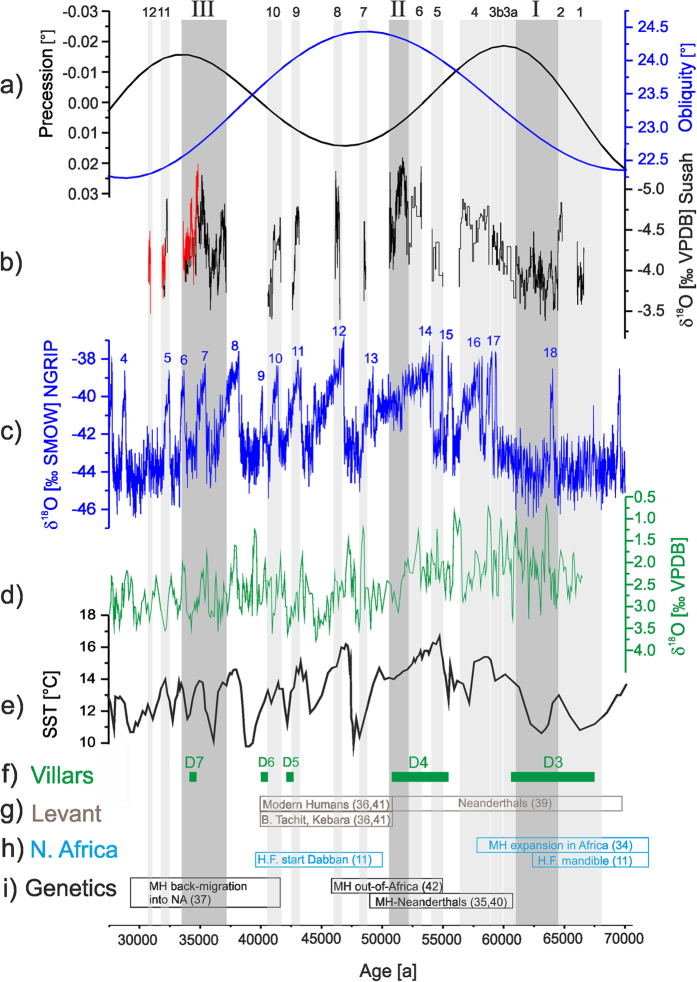

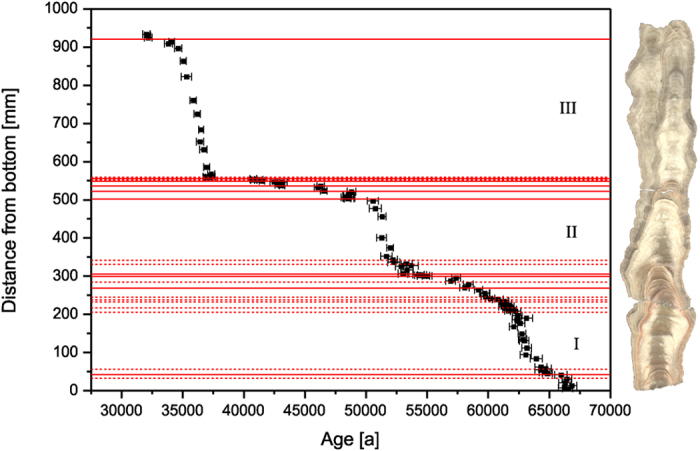

The presence of speleothems in Susah Cave demonstrates that effective rainfall must have been locally significantly higher in the past, allowing for episodic groundwater recharge in coastal northeast Libya. SC-06-01 formed episodically during the last glacial period between 67 and 30 ka (Fig. 2). We identify three sustained speleothem growth phases (Fig. 2, phases I, II and III) and 12 minor growth phases (phases 1 to 12) during the last glacial period (SI, Figs S3 and S4) during which increased aquifer recharge led to speleothem formation in Susah Cave. The three main sustained growth phases represent about 75% of stalagmite deposition. The SC-06-01 δ13Ccalcite record (SI, Fig. S8) supports the interpretation that the sustained growth phases I, II and III represent times of higher water availability and hence North African wet phases. At times of more water availability the vegetation density increases and leads to higher pCO2 which in turn leads to increased carbonate dissolution in the epikarst. Consequently, phases I, II and III exhibit higher growth rates. During phases I, II and III we find lower δ13Ccalcite values, while the short growth phases, particularly between 50 and 40 ka, are characterised by higher δ13Ccalcite values. These compositions likely result from changes in vegetation density, C4 vs. C3 vegetation, or prior calcite precipitation. At times of less water availability a relative increase of C4 vegetation would yield higher δ13Ccalcite values. Lower vegetation density, also a result of less water availability, likewise leads to higher δ13Ccalcite values. And increased prior calcite precipitation as a results of drier conditions also gives rise to higher δ13Ccalcite values. All this strongly indicates that the main growth phases I, II and III represent major North African wet phases. Two of the phases during which the speleothem grew rapidly, SC-06-01 phase I (65 to 61 ka) and phase III (37.5 to 33.5 ka), occur ~3000 years before maxima in Northern Hemisphere summer insolation13, arising from precession minima (Fig. 3). This supports a precessional forcing of runoff14 and freshwater supply to the Mediterranean Sea6, as well as reduced aeolian dust supply to both the Mediterranean15 and the eastern Atlantic16. Rainfall changes in North Africa and the surrounding region have previously been ascribed to meridional migrations of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and its attendant monsoon belt14,17. Cyrenaica is too far north to be directly influenced by the monsoon, but the coherence of variability in SC-06-01 and the precessional control at low latitudes suggests a teleconnection. Most likely, rainfall in Cyrenaica reflects enhanced convergence at 25–40°N as a consequence of the contraction of the Hadley cell, as suggested by General Circulation Model (GCM) experiments18 and proxy data19.

Figure 2. Chronology of SC-06-01.

U-Th ages are shown vs distance from the bottom of the stalagmite. The polished sections of the stalagmite are shown on the right for comparison. Red lines indicate positions of red dust layers visible in the speleothem. Solid red lines represent red layers associated with a hiatus, red layers without a detectable hiatus within dating uncertainties are marked by dotted red lines. The three main growth phases are the sections I, II and III.

Figure 3.

Speleothem δ18Ocalcite record (b) from northern Libya (Susah), numbers on top of the grey bars indicate SC-06-01 growth phases. The red data points of the SC-06-01 δ18O record refer to the twin stalagmite near the top. Dark grey bars indicate main phases I, II and III of sustained growth and light grey bars indicate phases 1 to 12 of short growth intervals. Comparison of the δ18Ocalcite with (a) Northern Hemisphere obliquity (blue) and precession (black) changes13, (c) NGRIP δ18O24 (blue numbers on top of the NGRIP record indicate Greenland Interstadials), (d) Mediterranean planktonic δ18O27, (e) Mediterranean SST28, (f) timing of discontinuities (green bars) in Villars cave speleothem21, durations of D5, D6 and D7 are not resolved by the age model of Vil9, (g,h) timing of archaeological evidence in North Africa and the Levant, (i) timing of genetically derived events in human evolution. Note that the scale is reversed for precession, the Mediterranean δ18O and the SC-06-01 δ18O record.

A shorter main phase of sustained speleothem growth, phase II (52.5 to 50.5 ka), is not related to a precession minimum, and therefore reflects a different component of the climate system. SC-06-01 phase II occurs ~ 3000 a before a maximum in obliquity (Fig. 3). This is the first terrestrial archive-based support of the model-based hypothesis18 that North African precipitation is enhanced during both maximum obliquity and minimum precession. Indeed, according to GCM results the impact of obliquity on insolation should be stronger during maximum precession18, and this is consistent with what we observe in SC-06-01 phase II.

A comparison between speleothem growth phases and insolation at 30°N and 60°N (SI, Figs S11 and S12) indicates that increased North African precipitation during the last glacial period could have been caused by the insolation gradient between mid and high latitudes. Phases I and III occurred just before peaks of the gradient in winter insolation between 60°N and 30°N (SI, Fig. S11b), whilst phase II occurred before a peak of gradient in summer insolation (SI, Fig. S12b). This mixed forcing indicates that increased water supply to North Africa can be the consequence of more than one configuration of insolation, in a way that is perhaps analogous to today’s North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Increasing insolation at 60°N relative to 30°N (SI, Figs S11 and S12) could more permanently reduce the gradient between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High, leading to a prolonged NAO−-like scenario, with wet climate in southern Europe and northern Africa while dry and cold conditions prevail in central and northern Europe20. This idea receives support from the fact that discontinuities in a stalagmite from Villars cave (France)21, interpreted as cold and dry phases in Europe, coincide with humid phases recorded by SC-06-01 (Fig. 3). The relationship between winter insolation and NAO−-like winter precipitation is straightforward during phases I and III, but a less direct mechanism must connect summer insolation and NAO−-like conditions during phase II. This may reflect the fact that winter precipitation in North Africa is largely driven by the North Atlantic surface heat budget22, which is influenced by both winter and summer insolation.

A key new observation in the SC-06-01 record is that all three main phases of speleothem growth occur before the corresponding orbital peak, and so rainfall occurs during increasing obliquity or decreasing precession, and not at maximum or minimum values respectively. The timing of growth phases found in SC-06-01 is precise to less than 300 a (2σ). The wet phases are out of phase with peak precession and obliquity by ~3000 a (Fig. 3). The observation that coastal North African rainfall precedes precession minima by ~3000 a is inconsistent with the accepted phase relationship between runoff from North Africa and precession, inferred from the timing of sapropel formation in the eastern Mediterranean6,23. Based on the radiocarbon age control on the Holocene Sapropel 1, and astrochronological arguments for the Neogene6, peak monsoonal runoff has been considered to lag peak precession minima by ~3000 a. Coastal rainfall is therefore out of phase with the monsoonal rainfall responsible for sapropel formation, which could also explain the shift in timing of Atlantic dust minima16 relative to that of sapropels. It seems likely that during the first millennia of the African Humid Periods, dust transport was suppressed by northern rainfall as recorded in SC-06-01. During the later millennia of these humid periods, rainfall further south suppressed dust transport and enhanced run off, which eventually led to sapropel deposition.

Growth phases and Greenland Interstadials

Growth phases in Susah Cave are not only controlled by orbital insolation. A succession of minor growth episodes of SC-06-01 mark millennial changes in water availability. Most of these minor episodes (phases 2, 3b, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11) coincided with Greenland Interstadials (GIS) (Fig. 3) as recorded in the NGRIP δ18O record24 (although they are numbered differently), indicating increased effective rainfall in northern Africa during times of rapid Northern Hemisphere warming. This is consistent with a marine MIS 3 record from the Western Mediterranean Sea, which shows stadials with lower sea-surface temperatures and higher aridity, and interstadials with higher continental humidity25. However, some of the minor growth phases in SC-06-01 (1, 3a, 5 and 12) coincide with cold periods in Greenland. This phenomenon has not previously been recognised for North African rainfall, and further investigation will require additional records from the region with age control as good as SC-06-01.

Changes in δ18O in speleothem calcite can be driven by a variety of effects7, for example, by changes of the rainwater source, moisture trajectories, ocean surface water composition (ice volume), amount effect, air temperature, and local effects in the cave such as drip rate, pCO2 or cave air temperature26. The position of Susah cave (Fig. 1) suggests that the main precipitation source is the Mediterranean Sea, but Atlantic influences are also likely. In Fig. 3 the SC-06-01 δ18O record is compared to δ18O records from Mediterranean δ18Osea27 and NGRIP δ18Oice24 as well as Mediterranean sea-surface temperature (SST)28. δ18Osea and SST show coherent patterns, consistent with a Mediterranean source for at least some rainfall at Susah cave. Changes in global ice volume between 65 and 30 ka may be an additional factor controlling the absolute value of δ18O in SC-06-01 on timescales ~10 ka, but this is probably not first-order effect on the high-frequency δ18Ocalcite changes recorded by SC-06-01 since ice volume-related source changes are not known on Dansgaard-Oeschger frequencies. However, comparison of the SC-06-01 δ18Ocalcite record with δ18Oice from NGRIP also indicates a high degree of correspondence, and the two records appear to be in-phase (Fig. 3 and SI, Fig. S9 and S10). This is true for both precessional and millennial timescales, regardless of the phasing with interstadials/stadials. Part of the SC-06-01 record is duplicated along a parallel secondary growth axis (Fig. 3), and this partial replication confirms the isotope pattern of SC-06-01. The correlation of the SC-06-01 and NGRIP data series indicates a North Atlantic influence on rainfall composition in North Africa, with warm periods in Greenland corresponding to isotopically more negative rainfall in Libya. This does not seem to arise from the isotopic ‘amount effect’ as found for speleothems in the Levant29, although some influence of the rainfall amount on the δ18O record cannot be excluded. For SC-06-01, maximum speleothem growth likely reflects maximum water availability, but the main growth phases I and II in our speleothem correspond to both higher (-3.8‰ between 65 and 61 ka) and lower δ18O values (-5.3‰ between 52.5 and 50.5 ka). This means that there are independent controls on rainfall amount and water isotopic composition. Similarity between relative changes in the North Atlantic system (NGRIP) and δ18Ocalcite therefore indicate a partial Atlantic source of the rainfall recorded in SC-06-01, perhaps via the frequency and severity of Atlantic storms influenced by the Atlantic SST. An Atlantic source is also implied by the δ18Ocalcite values, which are low relative to expectations for the Mediterranean region at this time30. We therefore interpret the isotopic variability in the SC-06-01 record as indicating that warm phases in Greenland correspond to increased advection of Atlantic-sourced moisture to Libya. This interpretation is consistent with GCM results, which show enhanced advection of moisture from the Atlantic across coastal North Africa during Northern Hemisphere warm phases22,31.

Implications for modern human dispersal and migration

Our speleothem record not only reveals important insights into North African hydrology changes during the last glacial period, but also sheds light on the highly variable environmental boundary conditions for human migration and dispersal during this critical time period. North Africa has been suggested to be a potential ‘launch pad’ for modern human migration into Eurasia32, and advantageous hydroclimate conditions, as identified in our record, are the primary limitation on the ability of the North African region to play this role. Migration of modern humans out of the sub-Sahara region into the North African realm would have been possible during MIS 5 due to a Sahara wet phase resulting in a green Sahara scenario33 and connected river systems34,35. However, subsequent migration and/or dispersal patterns north of the Sahara between 70 and 45 ka are still unclear. Our record shows that northern Africa remained humid during most of MIS 4 after the “green Sahara” phase ended about 72 ka ago. We show that North Africa experienced a sustained wet phase with favourable conditions for humans at 65–61 ka (SC phase I), a time when the Saharan area was dry36, but modern human populations show a major expansion in Africa37. Modern human remains have been found in Haua Fteah cave, only a few kilometres from Susah Cave, in a layer dated to about 73–65 ka11. Our results suggest that modern human presence and expansion in North Africa can be assigned to the SC phase I wet period recorded in our stalagmite.

The SC-06-01 palaeohumidity record furthermore provides a chronological and palaeoenvironmental framework for at least three subsequent major events in modern human migration and dispersal: a) interbreeding of modern humans with Neanderthals38, b) migration of modern humans into Eurasia39 and c) back-migration of a non-African lineage into North Africa40.

Our data suggest that SC wet phase II between 52.5–50.5 ka is a potential period during which modern human and Neanderthal interbreeding was first possible, perhaps in the Levant. There is independent evidence for humid conditions in the Levant broadly between 60 and 45 ka41. This indicates that synchronous humid conditions in North Africa and the Levant prevailed between 52.5 and 50.5 ka possibly along the entire North African coast, providing favourable habitats and migration routes for modern humans. Our results therefore suggest that modern humans expanded into the Levant during SC-06-01 wet phase II between 52.5 and 50.5 ka, where Neanderthals were present after 70 ka42. This supports and constrains DNA based timing of Neanderthal - modern human encounter and interbreeding between about 60 and 50 ka38,43. Archaeological evidence for modern humans in the Levant is found e.g. in Boker Tachit39 and Kebara44. Although the chronology for these sites is not secure39,45, modern human presence in the Levant can be broadly assigned to at least around or after 50 ka, while modern humans also remained in North Africa as demonstrated by the start of the Dabban in Haua Fteah11.

The further expansion of modern humans into Eurasia was suggested to have started around 48 ka ago39. A recent mtDNA based study by Posth et al.46 indicates a single dispersal out of North Africa starting less than 55 ka ago. Our record provides a possible chronological and environmental framework for this phase of human expansion, too. Dispersal into the Levant was likely to happen during SC wet phase II, possibly followed by the expansion into Eurasia, perhaps during GIS 1247 and possibly triggered by the predominantly dry period that started in North Africa after the end of SC wet phase II around 50 ka. Modern humans arrived in Europe no later than 41 ka as evidenced by a mandible found in Peştera cu Oase48.

The back-flow of modern humans from Eurasia into North Africa40 is another important movement during the last glacial period. Based on mtDNA evidence, Secher et al.40 show that a non-African lineage was moving back into Africa around 35 ka ago40. However, the DNA based estimate for the timing has large uncertainties and ranges between 24.6–46.4 ka. We suggest that this back-flow into the North African realm happened during a North African wet period recorded as SC phase III between 37.5 and 33.5 ka (SC phase III), providing environmental context for this event for the first time.

Conclusions

SC-06-01 records orbitally forced changes in water availability reflecting low-latitude migration of the ITCZ17 as well as high-latitude North Atlantic heat-forced changes in both rainfall amount and composition. This is the first time increased effective rainfall during the last glacial period has been directly demonstrated for the North African region, and extends the spatial distribution of known past increases in effective rainfall in North Africa5. This provides new insights for the critically under-constrained northern margin of the African Hadley Cell, and underscores the importance of North Africa as a key region for unravelling teleconnections between low- and high-latitude climate forcing.

Human dispersal and migration in North Africa during the last glacial period were closely linked to water availability. This new record provides important insights into environmental conditions in North Africa, covering the time of modern human dispersal north of the Sahara, interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans, modern human migration into Eurasia and back-flow of a non-African lineage into Africa.

Methods

The chronology of SC-06-01 is based on high-precision MC-ICPMS U-series dating of 116 sub-samples along the growth axis. Sample preparation and analytical protocols are detailed elsewhere12. Results are reported in full in the Supplementary Information (SI, Table S1). The depth-age model was derived using StalAge49. The dating results show episodic growth and age modelling was accordingly done section-wise using red dust layers as marker points to define growth intervals. Samples for stable isotope analyses were analysed using mass spectrometry as described in Spötl & Vennemann50. The isotopic composition of calcite was analysed in eighteen Hendy tests along individual growth layers from the central axis towards the flank of the stalagmite.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hoffmann, D. L. et al. Timing and causes of North African wet phases during the last glacial period and implications for modern human migration. Sci. Rep. 6, 36367; doi: 10.1038/srep36367 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Coath (University of Bristol) for his support on the Neptune. D. Richards (University of Bristol) helped to cut the three pieces of SC-06-01 along the growth axis. M. Wimmer (University of Innsbruck) assisted with the stable isotope measurements. This research was supported by a Natural Environment Research Council (UK) studentship to AO, a Thesiger-Oman Fellowship from Royal Geographical Society (UK), a BSRG Travel Grant to MR, and a NERC grant NE/J014133/1 to MR and DH. We thank three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments that helped to improve a previous version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.H., M.R. and C.S. designed the study. D.V. led the field campaign in Libya. M.R., D.V., A.O., G.M., M.L. and N.F. contributed to the fieldwork in Libya. M.R., A.O. and D.V. recovered the stalagmite. D.H. did U-series analyses and calculated the age model for SC-06-01. C.S. supervised the stable isotopes analyses and contributed to the interpretation. All authors contributed to data interpretation and writing.

References

- Drake N. A. et al. Palaeohydrology of the Fazzan Basin and surrounding regions: The last 7 million years. Paleogeogr. Paleoclimatol. Paleoecol. 263, 131–145, doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.02.005 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tjallingii R. et al. Coherent high- and low-latitude control of the northwest African hydrological balance. Nat. Geosci. 1, 670–675, doi: 10.1038/ngeo289 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scaillet S., Vita-Scaillet G. & Rotolo S. G. Millennial-scale phase relationships between ice-core and Mediterranean marine records: insights from high-precision Ar-40/Ar-39 dating of the Green Tuff of Pantelleria, Sicily Strait. Quat. Sci. Rev. 78, 141–154, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.08.008 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa K., Russell J., Konecky B. & Lamb H. Isotopic reconstruction of the African Humid Period and Congo Air Boundary migration at Lake Tana, Ethiopia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 83, 58–67, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.10.031 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasse F. Diatom-inferred salinity and carbonate oxygen isotopes in Holocene waterbodies of the western Sahara and Sahel (Africa). Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 737–767, doi: 10.1016/s0277-3791(01)00125-1 (2002). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler M., Tuenter E. & Lourens L. J. The precession phase of the boreal summer monsoon as viewed from the eastern Mediterranean (ODP Site 968). Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1481–1490, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.03.011 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild I. J. et al. Modification and preservation of environmental signals in speleothems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 75, 105–153, doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.08.003 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaks A., Bar-Matthews M., Matthews A., Ayalon A. & Frumkin A. Middle-Late Quaternary paleoclimate of northern margins of the Saharan-Arabian Desert: reconstruction from speleothems of Negev Desert, Israel. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 2647–2662, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.014 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brook G. A. et al. Djara Cave in the Western Desert of Egypt: Morphology and evidence of Quaternary climatic change. Cave and Karst Science 29, 57–66 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- McBurney C. B. M., Trevor J. C. & Wells L. H. The Haua Fteah Fossil Jaw. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 83, 71–85, doi: 10.2307/2844156 (1953). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douka K. et al. The chronostratigraphy of the Haua Fteah cave (Cyrenaica, northeast Libya). J. Hum. Evol. 66, 39–63, doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.10.001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D. L. et al. Procedures for accurate U and Th isotope measurements by high precision MC-ICPMS. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 264, 97–109 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Berger A. & Loutre M. F. Insolation values for the climate of the last 10000000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 297–317, doi: 10.1016/0277-3791(91)90033-q (1991). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohling E. J. et al. African monsoon variability during the previous interglacial maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 202, 61–75, doi: 10.1016/s0012-821x(02)00775-6 (2002). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrasoana J. C., Roberts A. P. & Rohling E. J. Magnetic susceptibility of eastern Mediterranean marine sediments as a proxy for Saharan dust supply? Marine Geology 254, 224–229, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2008.06.003 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- deMenocal P. et al. Abrupt onset and termination of the African Humid Period: rapid climate responses to gradual insolation forcing. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 347–361, doi: 10.1016/s0277-3791(99)00081-5 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns S. J., Fleitmann D., Matter A., Neff U. & Mangini A. Speleothem evidence from Oman for continental pluvial events during interglacial periods. Geology 29, 623–626, doi: (2001 ). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuenter E., Weber S. L., Hilgen F. J. & Lourens L. J. The response of the African summer monsoon to remote and local forcing due to precession and obliquity. Glob. Planet. Change 36, 219–235, doi: 10.1016/s0921-8181(02)00196-0 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. A. et al. Interhemispheric symmetry of the tropical African rainbelt over the past 23,000 years. Nat. Geosci. 4, 42–45, doi: 10.1038/ngeo1039 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner H. et al. North Atlantic Oscillation - Concepts and studies. Surv. Geophys. 22, 321–382, doi: 10.1023/a:1014217317898 (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genty D. et al. Precise dating of Dansgaard-Oeschger climate oscillations in western Europe from stalagmite data. Nature 421, 833–837, doi: 10.1038/nature01391 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayshaw D. J., Woollings T. & Vellinga M. Tropical and Extratropical Responses of the North Atlantic Atmospheric Circulation to a Sustained Weakening of the MOC. J. Clim. 22, 3146–3155, doi: 10.1175/2008jcli2594.1 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lourens L. J. et al. Evaluation of the Plio-Pleistocene astronomical timescale. Paleoceanography 11, 391–413, doi: 10.1029/96pa01125 (1996). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson A. et al. A 60 000 year Greenland stratigraphic ice core chronology. Clim. Past. 4, 47–57 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A. et al. Links between marine and atmospheric processes oscillating on a millennial time-scale. A multi-proxy study of the last 50,000 yr from the Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean Sea). Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1623–1636, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.06.018 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlinghaus C., Scholz D. & Mangini A. Modelling fractionation of stable isotopes in stalagmites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 7275–7289, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2009.09.010 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprovieri M. et al. Centennial- to millennial-scale climate oscillations in the Central-Eastern Mediterranean Sea between 20,000 and 70,000 years ago: evidence from a high-resolution geochemical and micropaleontological record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 46, 126–135 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Martrat B. et al. Abrupt temperature changes in the Western Mediterranean over the past 250,000 years. Science 306, 1762–1765 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Matthews M., Ayalon A. & Kaufman A. Late Quaternary Paleoclimate in the Eastern Mediterranean Region from Stable Isotope Analysis of Speleothems at Soreq Cave, Israel. Quat. Res. 47, 155–168 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Rohling E. J. Environmental control on Mediterranean salinity and delta O-18. Paleoceanography 14, 706–715, doi: 10.1029/1999pa900042 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. et al. Simulating the transient evolution and abrupt change of Northern Africa atmosphere-ocean-terrestrial ecosystem in the Holocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 1818–1837, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.03.002 (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balter M. Was North Africa The Launch Pad For Modern Human Migrations? Science 331, 20–23, doi: 10.1126/science.331.6013.20 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake N. A., Blench R. M., Armitage S. J., Bristow C. S. & White K. H. Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 458–462, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012231108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard T. J., Ramirez J. A., Barton N., Rogerson M. & Brücher T. Were rivers flowing across the Sahara during the last interglacial? Implications for human migration through Africa. PloS one 8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne A. H. et al. A humid corridor across the Sahara for the migration of early modern humans out of Africa 120,000 years ago. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 16444–16447, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804472105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake N. A., Breeze P. & Parker A. Palaeoclimate in the Saharan and Arabian Deserts during the Middle Palaeolithic and the Potential for hominin dispersals. Quat. Int. 300, 48–61, doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2012.12.018 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellars P. Why did modern human populations disperse from Africa ca. 60,000 years ago? A new model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 9381–9386, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510792103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman S., Patterson N., Li H., Pääbo S. & Reich D. The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans. PLoS Genet 8, e1002947, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002947 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hublin J. J. The modern human colonization of western Eurasia: when and where? Quat. Sci. Rev. 118, 194–210, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.08.011 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Secher B. et al. The history of the North African mitochondrial DNA haplogroup U6 gene flow into the African, Eurasian and American continents. Bmc Evolutionary Biology 14, 17, doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-109 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almogi-Labin A. et al. Climatic variability during the last similar to 90 ka of the southern and northern Levantine Basin as evident from marine records and speleothems. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 2882–2896, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.07.017 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shea J. J. Transitions or turnovers? Climatically-forced extinctions of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the east Mediterranean Levant. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 2253–2270, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.08.015 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Centeno H., Hubbe M., Hanihara T., Stringer C. & Harvati K. Testing modern human out-of-Africa dispersal models and implications for modern human origins. J. Hum. Evol. 87, 95–106, doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.06.008 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo N. R. et al. New radiocarbon dating of the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic in Kebara Cave, Israel. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 2424–2433, doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.05.010 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zilhão J. In Dynamics of Learning in Neanderthals and Modern Humans Volume1: Cultural Perspectives (ed Akazawa T. et al.) (Springer: Japan, , 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Posth C. et al. Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe. Current Biology, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller U. C. et al. The role of climate in the spread of modern humans into Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 273–279, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.11.016 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkaus E. et al. An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 11231–11236, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035108100 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz D. & Hoffmann D. L. StalAge - An algorithm designed for construction of speleothem age models. Quat. Geochronol. 6, 369–382, doi: 10.1016/j.quageo.2011.02.002 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spötl C. & Vennemann T. W. Continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometric analysis of carbonate minerals. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 1004–1006, doi: 10.1002/rcm.1010 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.