Short abstract

To achieve the UN's goals worldwide, less developed countries need to address weaknesses in health systems and policy makers need to look beyond aggregate national figures to inequalities in outcomes

In September 2000 the largest ever gathering of heads of state ushered in the new millennium by adopting the UN Millennium Declaration.1 The declaration, endorsed by 189 countries, was then translated into a roadmap setting out goals to be reached by 2015.2

The eight goals in the section on development and poverty eradication are known as the millennium development goals. They build on agreements made at major United Nations' conferences of the 1990s and represent commitments to reduce poverty and hunger, to tackle ill health, gender inequality, lack of education, lack of access to clean water, and environmental degradation (box). The big difference from their predecessors is that rather than just set targets for what developing countries aspire to achieve, the goals are framed as a compact that recognises the contribution that developed countries can make through fair trade, development assistance, debt relief, access to essential medicines, and technology transfer. Without progress in these areas (summarised in the final goal) the poorest countries will face an uphill struggle to achieve the other goals. The notion of the goals as a compact between North and South was reaffirmed at the international conference on financing development in Monterrey, Mexico, in 2002.3

Figure 1.

Achieving the millennium development goals requires steep declines in maternal and child mortality

Credit: DIETER TELEMANS/PANOS

Health and the millennium development goals

Health is central to the achievement of the millennium development goals—both in its own right (see goals 4, 5, and 6), and as a contributor to several others. For instance, the impact of poverty on ill health is well known and extensively documented. Ill health can also be an important cause of poverty through loss of income, catastrophic health expenses, and orphanhood. Thus improving health can make a substantial contribution to target 1, which aims to halve between 1990 and 2015 the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day. Although this article focuses on health, the millennium development goals should be considered as a mutually reinforcing framework contributing interactively to human development.

Are international goals worthwhile?

Sceptics may question whether it is worthwhile to have ambitious goals of this nature, given the patchy track record of the implementation of previous international declarations. Although goals and targets by themselves cannot achieve change, and although the monitoring progress is fraught with difficulties, we believe they are worthwhile for several reasons.

First and foremost they are a means, if used well, for holding to account those responsible for providing health services, and the accountability cuts both ways—for developing and developed countries. Secondly, they help define the role of health in development. Three of the eight goals, eight of the 18 targets, and 18 of the 48 indicators relate to health—so no one can say that development is just about economic growth. Thirdly, they provide a focus for development efforts and a lens through which to assess government plans, budgets, and poverty reduction strategies: do such efforts prioritise activities which will help meet the millennium development goals? Lastly, they demonstrate, beyond any doubt, the need for urgent action by showing how far progress lags behind expectations.

Millennium development goals focused on health

Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Achieve universal primary education

Promote gender equality and empower women

Reduce child mortality

Improve maternal health

Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

Ensure environmental sustainability

Develop a global partnership for development See www.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB111/eeb1113c1.pdf for targets within each goal

A mixed picture at half time

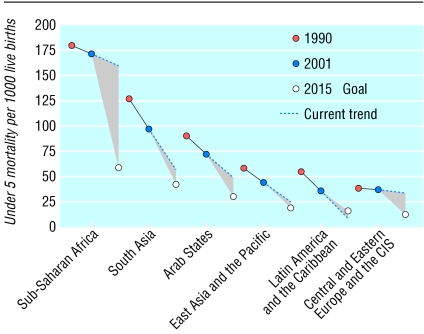

With 1990 as the base year for the millennium development goals, the score at half time is decidedly mixed. Some countries have made impressive gains and are “on track,” but many more are falling behind. The situation is not encouraging for goals related to lowering child and maternal mortality and infectious diseases, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. For mortality in children under 5, for example, the developing world has managed only a 2.5% average annual rate of reduction during the 1990s, well short of the target of 4.2%.4 In 16 countries (14 of which are in Africa) levels of under 5 mortality are currently higher than those in 19905; figure 1 summarises progress by region. Although the largest number of hungry people live in Asia, food production is increasing and the number of hungry people is declining, while in Africa the number is increasing and one third of the population is under-nourished.6 With more than 500 000 women a year dying in pregnancy and childbirth, faster progress on reducing maternal mortality also remains a key challenge. Maternal death rates are 100 times higher in sub-Saharan Africa than in many high income countries. However, the good news is that, outside sub-Saharan Africa, some strong progress has been made in increasing the rate of attended deliveries: for example, the percentage of deliveries with a skilled attendant rose by two thirds in southeast Asia and north Africa between 1990 and 2000.7

Fig 1.

Mortality in children under 5 years, 1990-2001, current trend (dotted line), and millennium development goals targets for 2015.6 Used by permission of Oxford University Press

Despite success in selected countries, the prospect of falling short overshadows the other health related targets, particularly as a result of the worsening global pandemic of HIV/AIDS, which has reversed life expectancy and economic gains in many parts of Africa. Malaria, tuberculosis, access to safe water and sanitation, and use of solid fuel as an indicator of indoor air pollution have similar prospects. The 2003 Human Development Report puts the situation starkly: “If global progress continues at the same pace as in the 1990s, only the millennium development goals of halving poverty and halving the proportion of people without access to safe water stand a realistic chance of being met, thanks mainly to China and India. Sub-Saharan Africa would not reach the poverty goals until the year 2147 and for child mortality until 2165.”6

Measuring progress

Although overall trends are clear, much remains to be done if we are to get a more accurate picture of what is really happening. A recent high level meeting on the health goals noted: “We cannot count the dead in the vast majority of the world's poorest countries—paradoxically these are the countries where the disease burden is greatest. In sub-Saharan Africa fewer than 10 countries have vital registration systems that produce viable data... The considerable investments in measuring health outcomes, often to monitor the effectiveness of donor-driven programmes... too often do not strengthen national health information systems.”8

Sound information is essential for tracking progress, evaluating impact, attributing change to different interventions, and guiding decisions on programme scope and focus. A key issue is that many different development partners—particularly those providing financial resources—each impose their own monitoring demands on countries. These are largely designed to suit donors' reporting requirements, rather than to help countries make strategic decisions. The result is that countries are overwhelmed and fragile information systems are unable to cope. The Health Metrics Network—a new coalition of countries, international agencies, bilateral and multilateral donors, foundations and technical experts—seeks to address this problem by persuading partners to focus on strengthening national information systems rather than particular sets of indicators.5

Ends and means

Clearly, the goals do not say everything that needs to be said about health and development. It is best to think of them as a kind of shorthand for some of the most important outcomes that development should achieve: fewer women dying in childbirth, more children surviving the early years of life, dealing with the catastrophe of HIV/AIDS, making sure people have access to lifesaving drugs. The millennium development goals represent desirable ends; they are not a prescription for the means by which those ends are to be achieved. They say nothing, for example, about the importance of effective health systems, which are essential to the achievement of all of the health goals, or the importance of rural infrastructure (roads, telephones, etc) in reducing maternal mortality. Similarly, the goals focus on communicable diseases, when we know that non-communicable diseases and injuries contribute as much or more to the total burden of disease in many countries. In this regard, WHO has argued that an overall measure of mortality is included among the indicators of progress. In addition, some countries chose to broaden the range of indicators to encompass priorities not covered by the goals.

Whose goals are they anyway?

National ownership is important. There is a risk that the millennium development goals are seen by some developing countries as being of prime concern to donors. They fear they will be used as a condition for the receipt of aid. In addition, the restricted focus of the goals, and the fact that they are a product of political negotiation, gives rise to concern that other hard-fought goals—such as those agreed in Cairo on reproductive health9—will be forgotten. It is encouraging, therefore, that some countries are choosing to include reproductive health data in their annual reports on the millennium development goals and that others have adapted the targets to their own national context, in some cases setting national targets which are more ambitious than the global ones.

Nevertheless, progress on goal 8—particularly in relation to fair trade, debt relief, and progress toward the UN target of 0.7% of gross national income for development assistance—has been generally disappointing. Compared with $57.6bn given in 1990, $56.5bn was given in 2002—a drop from 0.33% to 0.23% of gross national income in donor countries (an additional $16bn pledged by 2006 amounts to only 0.26% of gross national income).6 However, the UK's chancellor of the exchequer has recently announced the intention of the UK government to increase expenditure on aid to reach 0.7% of gross national income by 2013 at the latest.10

Who benefits if the goals are achieved?

The health goals are expressed as national averages, rather than gains among poor or disadvantaged groups. This means that significant progress in non-poor groups can result in the achievement of goals even though only minor improvements in the health of the poorest have been made.11 The use of aggregate data may mask growing inequalities, but such inequalities are not inevitable, as countries such as Guatemala and Bangladesh have shown.5

What needs to be done?

The problem is not simply a lack of effective interventions. There is, of course, a need for new drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics—and thus an important research agenda in relation to the millennium development goals. However, countries are not “off track” because knowledge is lacking on how to treat a child with pneumonia, to prevent diarrhoea, to deliver babies safely, or even to prolong the life of people living with AIDS. But effective interventions often fail to reach the people who need them.

Resources are important. Current health spending in most low income countries is insufficient for achieving the health goals. We have global estimates of what is needed—a doubling of aid from around $50bn in 2001 to $100bn a year for the goals as a whole; $10bn per year total spending on HIV/AIDS; and a fivefold increase in donor spending on health.12 The proposed International Finance Facility could help to achieve the needed increase by using long term commitments from government donors to leverage immediate and additional resources from private markets13—thus enabling the frontloading of aid when it is most needed.14 Progress, though, cannot depend on aid alone: reducing trade barriers erected by wealthy nations to exports from developing countries can make a big difference. Developing countries too have to make greater efforts. In this context, African ministers set their own target to increase health spending (for example, to 15% of total government expenditure15).

Although few would dispute the need for more money, there are concerns about the current capacity of poor countries to effectively absorb major increases in aid. In addition, a debate remains between ministries of finance, the Bretton Woods institutions, and others about the extent to which a rapid scale-up of aid will affect macroeconomic stability.12 Increases in aid can influence exchange rates and competitiveness, but HIV/AIDS and other major causes of ill health will hit economies hard for a long time. Fiscal policy should reflect the urgency of the situation in countries where high death rates among civil servants, teachers, police, and health workers threaten the stability of societies.

More money is only part of the picture. Progress equally depends on getting policies right; making the institutions that implement them function effectively; building health systems that work well and treat people fairly; generating demand for better and more accessible services; and—perhaps the most neglected factor of all—ensuring there are enough staff to do all the work that is required.

In many countries, particularly in southern Africa, the shortage of health service and other public sector staff has now become one of the most serious rate limiting factors in scaling up the response to HIV/AIDS and other public health problems. The reasons for this crisis are multiple. Health workers are dying. They are leaving public service because the conditions are poor, and getting worse. They are seeking better paid jobs in the private sector, or leaving health care altogether for better paid jobs. They are migrating to countries that can pay more for their services within Africa. Others go further afield and add to the brain drain from sub-Saharan Africa. Although extensive analysis of these issues is available,16,17 a concerted attempt to remedy the situation has so far been wanting.

In summary

Achieving the health millennium development goals represents some of the greatest challenges in international development, not least because they include the goal of reversing the global epidemic of HIV/AIDS. To this we have to add the steep declines required in child and maternal mortality, where progress lags far behind aspirations in many parts of the world. Improving health outcomes will not be possible without major improvements in healthcare delivery systems, which in turn depend on changes in public sector management, new forms of engagement with the private sector (leading, for example, to wider availability of affordable drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics), more research directed at improving health systems, as well as policies and interventions well beyond the health sector itself. Moreover, improvements in health are essential if progress is to be made with the other millennium development goals, including the reduction of absolute poverty.

Summary points

Improving health outcomes will not be possible without major improvements in healthcare delivery systems

Improvements in health are essential for progress with other millennium development goals

Without more resources and changes in policies, the goals cannot be attained—but accelerated progress is possible

In answer to the question posed in the title, if none of the changes described in this article take place then the answer is almost certainly no, the goals cannot be attained. But accelerated progress is possible, and lies within reach. It is a matter of political choice in both the developed and developing world. We also know that substantial progress, even if it were to fall short of the targets set four years ago, could dramatically transform the lives of millions of the world's poorest people. The millennium development goals are one means of exerting the leverage that can make this happen.

We thank Becky Dodd and Carla Abou Zahr, WHO, for their comments and advice.

Contributors and sources: AH has had a longstanding interest in global health issues and has written articles on a range of relevant topics. AC is director of the department within the World Health Organization concerned with coordinating WHO's work on the health related millennium development goals. In addition to quoted publications, the article draws on discussions at the High Level Forum on the Health MDGs held in Geneva in January 2004. Both authors are guarantors of the paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.United Nations Millennium Declaration. New York: United Nations, 2000. (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 55/2. www.un.org/milleennium/declaration/ares552e.pdf (accessed 8 Jul 2004).)

- 2.Road map toward the implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration. New York: United Nations, 2002. United Nations General Assembly Document A56/326. www.eclac.cl/povertystatistcs/documentos/a56326i.pdf (accessed 8 July 2004).

- 3.Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development, Monterrey, Mexico, 18-22 March 2002. New York: United Nations, 2002.

- 4.World Bank. The millennium development goals for health: rising to the challenges. Washington: World Bank, 2004.

- 5.World Health Organization. World health report 2003: shaping the future. Geneva: WHO, 2003. www.who.int/whr/2003/en/ (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 6.United Nations Development Programme. Human development report, 2003. The millennium development goals: a compact among nations to end human poverty. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- 7.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. Progress towards the millennium development goals, 1990-2003. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mi/mi_coverfinal.htm (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 8.World Health Organization, World Bank. Monitoring the health MDGs. Issue paper 3 for the high level forum on the health MDGs. December 2003. www.who.int/hdp/en/IP3-monitoring.pdf (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 9.Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 5-13 September 1994. Chapter 7. www.unfpa.org/icpd/docs/index.htm (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 10.H M Treasury. Statement by the chancellor of the exchequer on the 2004 spending review. 12 July 2004. www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/spending_review/spend_sr04/spend_sr04_statement.cfm (accessed 15 Jul 2004).

- 11.Gwatkin D. Who would gain most from efforts to reach the MDGs for health? An enquiry into the possibility of progress that fails to reach the poor. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002. www1.worldbank.org/hnp/Pubs_Discussion/Gwatkin-Who%20Would%20-Whole.pdf (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 12.World Health Organization, World Bank. Resources, aid effectiveness and harmonisation. Issue paper 2 for the high level forum on the health MDGs. December 2003. www.who.int/hdp/en/IP2-resources.pdf (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 13.H M Treasury. International finance facility. 23 January 2003. www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/documents/international_issues/global_new_deal/int_gnd_iff2003.cfm (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 14.Lee K, Walt G, Haines A. The challenge to improve global health: financing the millennium development goals. JAMA 2004;291: 2636-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.African Development Forum. Abuja Declaration on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other related infectious diseases. 2001. www.uneca.org/adf2000/Abuja%20Declaration.htm (accessed 8 Jul 2004).

- 16.Stilwell B, Diallo K, Zurn P, Vujicic M, Adams O, Dal Poz M. Health workers and migration from low-resource countries—what can be done? Bull World Health Org (in press). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Narasimhan V, Brown H, Pablos-Mendez P, Adams O, Dussault G, Elzinga G, et al. Responding to the global human resource crisis. Lancet 2004:363: 1469-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]