Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association between the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene by emergency medical service (EMS) personnel and prehospital demographic factors and reasons for EMS calls.

Design

A retrospective, observational study.

Setting

Osaka City, Japan.

Participants

A total of 100 649 patients transported to medical institutions by EMS from January 2013 to December 2013.

Primary outcome measurements

The definition of difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene was EMS personnel making ≥5 phone calls to medical institutions until a decision to transport was determined. Multivariable analysis was used to assess the relationship between difficulty in hospital acceptance and prehospital factors and reasons for EMS calls.

Results

Multivariable analysis showed the elderly, foreigners, loss of consciousness, holiday/weekend, and night-time to be positively associated with difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. As reasons for EMS calls, gas poisoning (adjusted OR 3.281, 95% CI 1.201 to 8.965), trauma by assault (adjusted OR 2.662, 95% CI 2.390 to 2.966), self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning (adjusted OR 4.527, 95% CI 3.921 to 5.228) and self-induced trauma (adjusted OR 1.708, 95% CI 1.369 to 2.130) were positively associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene.

Conclusions

Ambulance records in Osaka City showed that certain prehospital factors such as night-time were positively associated with difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene, and reasons for EMS calls, such as self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning, were also positive predictors for difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene.

Keywords: emergency medical service, hospital acceptance, pre-hospital factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study assessed the relationship between difficulty in hospital acceptance and the prehospital factors such as demographic factors and reasons for emergency medical service (EMS) call for all patients transported to medical institutions by EMS in the third largest city with 2.2 million inhabitants in Japan, based on the population-based ambulance records.

The elderly, foreigners, loss of consciousness, holiday/weekend and night-time were positively associated with difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. As reasons for EMS calls, gas poisoning, trauma by assault, self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning and self-induced trauma were also positively associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene.

These results may not be generalised because this study was carried out in a Japanese big city and the emergency medical system in Japan is different from that in other countries.

Introduction

In Japan, when emergency patients call for emergency medical service (EMS), on-scene EMS personnel determine the appropriate emergency hospital best able to treat the patients according to their signs and symptoms. The EMS proceeds to transport the patient to the selected hospital after obtaining the hospital staff's agreement.1 Thus, difficulty in transporting the patient can occur at the scene in Japan. As a consequence, the time from a patient's call until hospital arrival lengthens2 and delays the start of emergent treatments, which might lead to worse patient outcomes.

Emergency room (ER) crowding is one of the major public health problems associated with ambulance diversion in the USA,3–5 and factors affecting ER crowding were suggested to be a balance of supply and demand in the ER, the treatments themselves and patient flow after treatment.6 Although the situation in which hospitals cannot receive emergency patients from ambulances is one of the serious social problems in Japan, it is unclear which prehospital factors, such as chronological factors, location of occurrence and patient condition, affect the transport of emergency patients to hospitals by EMS personnel.

The Osaka Municipal Fire Department has been collecting ambulance records on all patients transported to hospitals by EMS personnel in Osaka City, Japan, a metropolitan community with ∼2.6 million residents and 200 000 emergency dispatches every year. We hypothesised that demographic characteristics such as age and sex and prehospital factors such as location, time of day, day of week and reason for EMS call would influence the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. The aim of this study was to investigate the associations between the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene and these factors by reviewing a large number of ambulance records in Osaka City.

Materials and methods

Study design, population and setting

Our study was a retrospective observational study based on ambulance records in Osaka City. The study period was from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2013. All emergency patients for whom EMS personnel at the scene selected the hospital and then transported them to that institution were registered in our study. We excluded emergency patients who were either not transported or were transported to the hospitals requested by the patients and their family and those undergoing interhospital transport. The ambulance records in Osaka City are considered administrative records, and the requirement of obtaining patients' informed consent was waived because the data were anonymous.

EMS system and hospitals in Osaka City

Osaka City, the largest metropolitan community in western Japan, covers an area of 222 km2 and had a population of about 2.6 million in 2013. The municipal EMS system is basically the same as that in other areas of Osaka Prefecture, as previously described.7 The EMS system is operated by the Osaka Municipal Fire Department and is activated by phoning 119. In 2013, there were 25 fire stations with 60 ambulances and one dispatch centre in Osaka City. EMS life support is conducted 24 hours a day. Usually, each ambulance has a crew of three emergency providers including at least one highly trained prehospital emergency care provider, and the annual number of patients transported to medical institutions by EMS in this area is about 200 000. Osaka City had 186 hospitals (33 026 beds) in 2013.8 A total of 94 institutions, including six critical care centres, can accept life-threatening emergency patients from ambulances. In Osaka City, emergency dispatchers do not make phone calls to hospitals to determine patient acceptance. Rather, using the protocol established by the Osaka Municipal Fire Department, EMS ambulance crews at the scene select the appropriate medical institutions near the scene that are best able to treat emergency patients according to medical urgency or the patient's symptoms.

Data collection and quality control

Data were uniformly collected using specific data collection forms and included age, sex, foreigner or not, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, location of call, chronological factors such as time of day or day of week, time course of transport such as time of the call, time spent in contact with the patient, and time to hospital arrival, reason for EMS call and the number of phone calls made to hospitals by EMS personnel.

These data were completed by EMS personnel in cooperation with the physicians caring for the patient and then transferred to the information centre in the Osaka Municipal Fire Department. If the data sheet was incomplete, it was returned to the relevant EMS personnel for them to correct the data.

End point

The main end point was to determine factors associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. The definition of difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene was when EMS personnel needed to made ≥5 phone calls to medical institutions before the decision of which hospital to transport the patient to was made based on the guidelines regarding the transport and hospital acceptance of emergency patients in Osaka City.9

Statistical analysis

Patient and EMS characteristics between the two groups (<5 and ≥5 phone calls) were assessed by χ2 tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables. We calculated the OR and 95% CI with use of a logistic regression model to evaluate the factors associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene, and we considered potential factors that existed before the EMS personnel made contact with the emergency patient. These factors included age group (children aged <15 years, adults aged 15–64 years and elderly aged ≥65 years), sex (male or female), foreigner (yes or no), loss of consciousness (defined as GCS≤8 or not), location (home, public space such as store and station, workplace, healthcare facility such as a clinic or nursing home), time of day (daytime or night-time), day of week (weekday or holiday including weekend) and reason for the EMS call. In this study, reasons why a patient, the patient's family or bystanders would call an ambulance included, among others, internal disease; gynaecological disease; fire accident (including natural disaster); water accident; traffic accident involving vehicle, ship or aircraft; industrial accident; disease and injury during sports; disease and injury while watching sports; trauma by assault; self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning; self-induced trauma; and other injury. According to these requests, EMS personnel at the scene phoned hospitals to determine whether they could receive emergency patients. In addition, we assessed the correlation between the time interval from first call to hospital until hospital acceptance and the number of phone calls.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical package V.22.0J (IBM Corp. Armonk, New York, USA). All tests were two-tailed, and p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

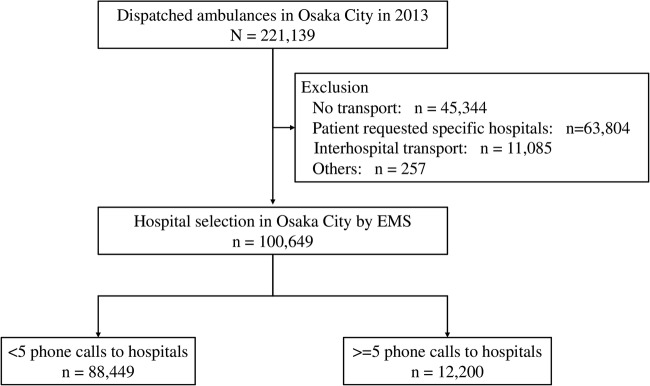

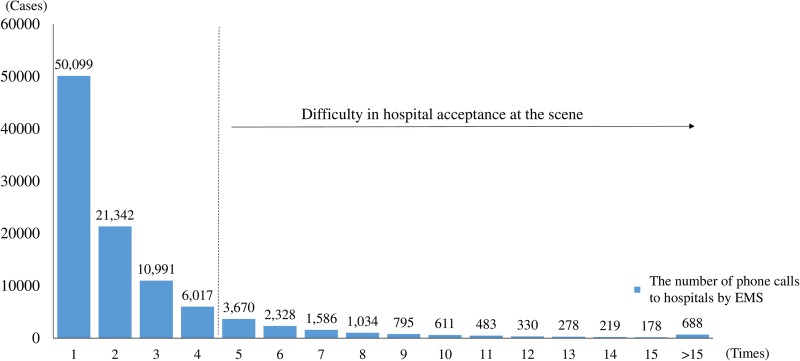

During the study period, a total of 221 139 emergency patients were documented in Osaka City. Of them, 100 649 were enrolled in this study. Excluded were 45 344 patients who were not transported by ambulances, 63 804 patients who were transferred to the hospitals requested by patients or their family, 11 085 patients who were transferred to a different hospital and 257 other patients (figure 1). Among these patients, a total of 12 200 emergency patients needed ≥5 phone calls by EMS personnel at the scene until a decision of hospital acceptance. The median number of calls was 2 (IQR 1–3), and ≥10 phone calls to hospitals by EMS personnel were needed for 2787 patients (2.8%) (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Patient flow in this study. EMS, emergency medical service.

Figure 2.

Histogram of the number of phone calls made to hospitals by emergency medical service (EMS) personnel at the scene.

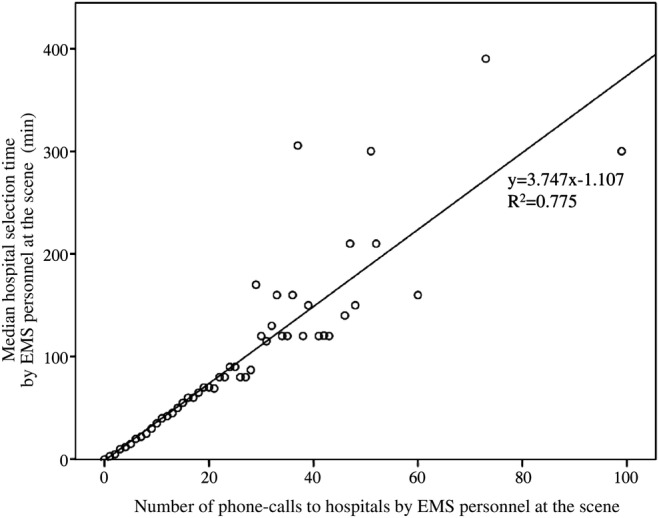

Figure 3 showed that the time interval from first call to hospital until hospital acceptance was well correlated with the number of phone calls (y=3.747x-1.107, R2=0.775).

Figure 3.

The correlation between time interval from first call to hospital until hospital acceptance. EMS, emergency medical service.

Characteristics of the emergency patients with <5 or ≥5 phone calls to hospitals by EMS personnel until the decision of hospital transport was made are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and number of phone calls to hospitals by EMS

| Number of phone calls to hospitals by EMS personnel |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| <5 | ≥5 | ||

| (n=88 449) | (n=12 200) | p Value | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 51 (28–72) | 54 (34–73) | <0.001 |

| Age group, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Children aged ≤14 years | 8444 (9.5) | 471 (3.9) | |

| Adults aged 15–64 years | 48 805 (55.2) | 7132 (58.5) | |

| Elderly aged ≥65 years | 31 200 (35.3) | 4597 (37.7) | |

| Male, n (%) | 48 586 (54.9) | 6871 (56.3) | 0.004 |

| Foreigners, n (%) | 191 (0.2) | 54 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Loss of consciousness (GCS≤8), n (%) | 4705 (5.3) | 858 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Location, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Home | 40 532 (45.8) | 6076 (49.8) | |

| Public space | 38 650 (43.7) | 5093 (41.7) | |

| Workspace | 2646 (3.0) | 192 (1.6) | |

| Healthcare facility | 484 (0.5) | 55 (0.5) | |

| Other | 6137 (6.9) | 784 (6.4) | |

| Time of day, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Daytime (09:00–17:00) | 39 275 (44.4) | 3026 (24.8) | |

| Night-time (17:00–09:00) | 49 174 (55.6) | 9174 (75.2) | |

| Day of week, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Weekdays | 57 569 (65.1) | 6866 (56.3) | |

| Weekends/holidays | 30 880 (34.9) | 5334 (43.7) | |

| Reason for EMS call, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Internal disease | 55 199 (62.4) | 7299 (59.8) | |

| Gynaecological disease | 1028 (1.2) | 26 (0.2) | |

| Fire accident (including natural disaster) | 167 (0.2) | 27 (0.2) | |

| Water accident | 29 (0.03) | 2 (0.02) | |

| Traffic accident involving car, ship or aircraft | 12 119 (13.7) | 1311 (10.7) | |

| Injury, poisoning and disease due to industrial accident | 1087 (1.2) | 124 (1.0) | |

| Disease and injury during sports | 697 (0.8) | 78 (0.6) | |

| Disease and injury while watching sports | 18 (0.02) | 2 (0.02) | |

| Asphyxia | 402 (0.5) | 57 (0.5) | |

| Gas poisoning not due to industrial accident and self-injury | 12 (0.01) | 6 (0.05) | |

| Trauma due to assault | 1378 (1.6) | 512 (4.2) | |

| Self-induced drug abuse and gas poisoning | 573 (0.6) | 325 (2.7) | |

| Self-induced trauma | 433 (0.5) | 103 (0.8) | |

| Other injury | 15 307 (17.3) | 2328 (19.1) | |

| Time from patient's call to contact by EMS, min, median (IQR) | 6 (4–7) | 6 (4–7) | 0.003 |

| Time from patient's call to hospital arrival, min, median (IQR) | 29 (23–37) | 57 (46–74) | <0.001 |

EMS, emergency medical service; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Compared with patients requiring <5 phone calls, those requiring ≥5 phone calls were more likely to be older (54 vs 51 years, p<0.001), to be male versus female (56.3% vs 54.9%, p=0.004), to have loss of consciousness (7.0% vs 5.3%, p<0.001), and have the emergency occur at night-time (17:00–09:00) (75.2% vs 55.6%, p<0.001) or on a holiday/weekend (43.7% vs 34.9%, p<0.001). As reasons for the EMS call, the proportions of trauma by assault (1.6% vs 4.2%) and self-induced drug abuse and gas poisoning (0.6% vs 2.7%) were greater in the group requiring ≥5 phone calls versus those requiring <5 phone calls. Although the time interval from the patient's call to contact with the patient by EMS was similar between the two groups, the interval from the patient's call to hospital arrival was longer for the patients requiring ≥5 phone calls than for those requiring <5 phone calls (57 vs 29 min, p<0.001).

Factors associated with ≥5 phone calls to hospitals by EMS personnel at the scene until the decision of hospital transport was made are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with ≥5 phone calls to hospitals by EMS personnel at the scene

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (versus adults) | |||

| Children | 0.375 | 0.340 to 0.414 | <0.001 |

| Elderly | 1.107 | 1.061 to 1.156 | <0.001 |

| Female (vs male) | 0.912 | 0.876 to 0.949 | 0.001 |

| Foreigners | 2.393 | 1.752 to 3.268 | <0.001 |

| Loss of consciousness (GCS≤8) | 1.234 | 1.140 to 1.336 | <0.001 |

| Location (compared with home) | |||

| Public place | 0.912 | 0.871 to 0.955 | 0.259 |

| Workplace | 0.645 | 0.550 to 0.758 | <0.001 |

| Healthcare facility | 0.834 | 0.627 to 1.109 | 0.212 |

| Other | 0.941 | 0.865 to 1.023 | 0.153 |

| Night-time (compared with daytime) | 2.426 | 2.321 to 2.536 | <0.001 |

| Weekends/holidays (compared with weekdays) | 1.362 | 1.262 to 1.470 | <0.001 |

| Reason for EMS request (compared with internal disease) | |||

| Gynaecological disease | 0.234 | 0.158 to 0.347 | <0.001 |

| Fire accident (with natural disaster) | 1.137 | 0.753 to 1.716 | 0.499 |

| Water accident | 0.413 | 0.098 to 1.749 | 0.230 |

| Traffic accident involving vehicle, ship or aircraft | 0.933 | 0.870 to 1.000 | 0.050 |

| Injury, poisoning and disease due to industrial accident | 1.415 | 1.157 to 1.731 | 0.001 |

| Disease and injury during sports | 1.253 | 0.986 to 1.594 | 0.065 |

| Disease and injury while watching sports | 1.068 | 0.245 to 4.660 | 0.930 |

| Asphyxiation | 1.154 | 0.870 to 1.532 | 0.320 |

| Gas poisoning not due to industrial accident and self-injury | 3.281 | 1.201 to 8.965 | 0.020 |

| Trauma due to assault | 2.662 | 2.390 to 2.966 | <0.001 |

| Self-induced drug abuse and gas poisoning | 4.527 | 3.921 to 5.228 | <0.001 |

| Self-induced trauma | 1.708 | 1.369 to 2.130 | <0.001 |

| Other injury | 1.214 | 1.152 to 1.279 | <0.001 |

EMS, emergency medical service; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Elderly patients (adjusted OR 1.107, 95% CI 1.061 to 1.156), foreigners (adjusted OR 2.393, 95% CI 1.752 to 3.268), loss of consciousness (adjusted OR 1.234, 95% CI 1.140 to 1.336), holiday/weekend (adjusted OR 1.362, 95% CI 1.262 to 1.470) and night-time (adjusted OR 2.426, 95% CI 2.321 to 2.536) were positively associated with ≥5 phone calls to hospitals by EMS personnel. As reasons for the EMS call, industrial accident (adjusted OR 1.415, 95% CI 1.157 to 1.731), gas poisoning not due to industrial accident and self-injury (adjusted OR 3.281, 95% CI 1.201 to 8.965), trauma by assault (adjusted OR 2.662, 95% CI 2.390 to 2.966), self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning (adjusted OR 4.527, 95% CI 3.921 to 5.228) and self-induced trauma (adjusted OR 1.708, 95% CI 1.369 to 2.130) were also positively associated with ≥5 calls to hospitals by EMS personnel. However, factors such as children (adjusted OR 0.375, 95% CI 0.340 to 0.414) and gynaecological disease (adjusted OR 0.234, 95% CI 0.158 to 0.347) were negatively associated with ≥5 calls to hospitals by EMS personnel.

Discussion

From the ambulance records of emergency patients in a large metropolitan city in Japan, we demonstrated that prehospital factors such as elderly patients, foreigners, loss of consciousness and occurrence at night-time or on weekends/holidays were associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene that required EMS personnel to make ≥5 phone calls to hospitals until the decision of transport was made. As reasons for the EMS call, factors including industrial accident, gas poisoning without industrial accident and self-injury, trauma by assault, self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning and self-induced trauma were also associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene.

Although the EMS system in western countries transports emergency patients to the ER and then selects the most appropriate hospital that can treat them, EMS personnel in Japan assess emergency patients at the scene and select the most appropriate hospital for them based on the EMS protocol by the Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan. Thus, the difference in the EMS system between communities would cause the ambulance diversion after the transport to ER in western countries and the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene in Japan. This descriptive study showing the actual situations causing difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene in Japan provides important clues for improving these factors in prehospital settings.

Several prehospital factors were associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. For example, the association of advanced age with the difficulty in hospital acceptance was consistent with that in a previous study in Japan.10 Most older patients have many complications or cannot explain their symptoms in detail to EMS personnel, and with increasing age, they tend to use an ambulance as a method of transport to an emergency department.11 Thus, advanced age might frequently lead to the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. Furthermore, foreigners were also associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. Although the nationality of foreigners was not specified in this study, emergency departments might not have been able to receive foreigners with emergency conditions who cannot speak Japanese because there were few multilingual staff at medical institutions in the Osaka area. However, patients with loss of consciousness (GCS≤8) were also associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene because it might be difficult for general hospitals to receive these severely ill patients. Although the reasons that hospitals could not receive emergency patients were unclear in this study, general reasons noted in a report from the Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan12 regarding why hospitals cannot accept emergency patients were ‘untreatable’ (22.9%), ‘all beds occupied’ (22.2%) and ‘under other patient operation or treatment’ (21.0%). To resolve the difficulty in hospital acceptance, we need to further assess the combination of factors present before and after hospital arrival.

Chronological factors such as night-time/weekend occurrence were also associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. In Japan, the number of medical institutions or medical staff that can treat emergency patients during night-time, weekends or holidays is low. Previous studies in the USA demonstrated that increasing the number of doctors, the deployment of senior physicians, and adjustments of staff schedules led to an improvement in ER crowding.13–15 Considering these results along with ours, the rotation of medical institutions that accept patients during non-working hours, increasing the number of medical staff, and increasing the salaries paid to night-time staff may help to resolve this problem. The time has come when we must work in cooperation with local autonomous bodies to take measures to resolve these problems.

This study underscored several reasons for EMS calls being associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. Both self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning and self-induced trauma were predictors of the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. Most patients causing self-induced injury often have psychological diseases,16 and medical staff in non-psychiatric emergency departments might refuse the request from EMS personnel to receive such patients because of the difficulty in treating them. In addition, these patients tend to call for ambulances and frequently visit emergency departments,17–19 which might also affect the difficulty in hospital acceptance. Trauma by assault was also one of the predictors of the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene, and emergency hospitals would hesitate to receive patients with such injuries because there are not emergency hospitals for the emergency transport of these patients by law in Japan, and it is difficult for staff to continuously monitor them in hospitals.

Gynaecological disease, however, was negatively associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. In 2006, several hospitals refused to accept a pregnant emergency patient with cerebral haemorrhage who was suspected of suffering an eclamptic seizure. As a result, she and her infant died, and this case became an important social problem across Japan.20 Since then, emergency medical systems for pregnant women with emergent conditions have been comprehensively improved, and EMS personnel at the scene can appropriately select hospitals to receive such patients,21 which might explain our result. In addition, children aged 0–14 years were also negatively associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene because the transport of paediatric emergency patients was properly conducted during the study period in Osaka.

Critical care centres in Japan accept many emergency patients with severe illnesses such as sepsis or trauma from ambulances and other emergency hospitals. Their ability to accept such patients has recently faced some limits because the number of patients to transport to critical care centres has exceeded their capacity. Therefore, the role of other emergency hospitals in accepting many patients into their hospitals is becoming important. One of our missions is to develop the emergency medical system so that many patients can be smoothly transported to hospitals with limited medical resources. The present study, which shows factors associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene, is informative in highlighting measures that need to be taken to resolve issues of difficulty in hospital acceptance in Japan.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, an important limitation of this study is that we did not obtain information on in-hospital outcomes and treatments of emergency patients after hospital arrival. Therefore, it was unclear how the difficulty in hospital acceptance would affect patient outcome after hospital arrival. After October 2014, we began to collect data including emergency patients' prognosis after hospital arrival and will address this issue in the near future.22 Second, this study uniformly defined the difficulty in hospital acceptance regardless of the patient's condition to assess differences by demographic factors or reason for EMS call. However, since there might be differences in the effects on the difficulty in hospital acceptance caused by severe conditions such as shock or loss of consciousness versus moderate/mild conditions such as high fever or cough, it is also important to further assess the difficulty in hospital acceptance according to the degree of urgency of the patient's condition. Third, the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene may be influenced by the experience and communication skills of EMS personnel to call hospitals. Fourth, these results may not be generalised because this study was carried out in a big Japanese city and the emergency medical system in Japan is different from that in other countries. Fifth, since this was an observational study, there might be unknown confounding factors that influenced our results. Finally, we did not, unfortunately, obtain information on how many of the forms returned were incomplete in this study. However, a population-based design with a large sample size to cover all emergency patients in Osaka City would serve to minimise this potential source of bias.

Conclusion

From ambulance records in a large urban community, we demonstrated that the prehospital factors of elderly patients, loss of consciousness, occurrence at night-time or on weekends/holidays, and foreigners were positively associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. Further, reasons for the EMS call including self-induced drug abuse/gas poisoning/trauma and trauma by assault were also positive predictors for the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene. This study highlighted factors associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene that can be informative for taking measures to resolve this problem in Japan.

Acknowledgments

The authors are greatly indebted to all of the EMS personnel working in the Osaka Municipal Fire Department.

Footnotes

Contributors: YK, TKi, TI and SH collected the data. YK and KK performed statistical analysis of the collected data. YK, TKi, TI, TKa and TS interpreted the data. YK, TKi, TI and TKa prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved this version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Pfizer Health Research Foundation (Tokyo, Japan).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine and Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ambulance Service Planning Office of Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan: 2014 Effect of first aid for emergency patients. http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/fieldList9_3.html (accessed 3 Nov 2015).

- 2.Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan: 2014 White book on Emergency Systems in Japan. http://www.fdma.go.jp/html/hakusho/h26/h26/pdf/part2_section5.pdf (accessed 3 Nov 2015).

- 3.Gallagher EJ, Lynn SG. The etiology of medical gridlock: causes of emergency department overcrowding in New York City. J Emerg Med 1990;8:785–90. 10.1016/0736-4679(90)90298-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glushak C, Delbridge TR, Garrison HG. Ambulance diversion. Standards and Clinical Practices Committee, National Association of EMS Physicians. Prehosp Emerg Care 1997;1:100–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squire BT, Tamayo A, Tamayo-Sarver JH. At-risk populations and the critically ill rely on disproportionately on ambulance transport to emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:341–7. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systemic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52:126–36. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irisawa T, Iwami T, Kitamura T et al. . An association between systolic blood pressure and stroke among patients with impaired consciousness in out-of-hospital emergency settings. BMC Emerg Med 2013;13:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan: 2013 Medical facilities survey. http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?lid=000001126755 (accessed 3 Nov 2015).

- 9.The guidelines regarding the transport and hospital acceptance of emergency patients in Osaka City. http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/attach/3071/00022885/osakashi.pdf (accessed 15 Sep 2016).

- 10.Suzuki M, Hori S. Characteristics of patients who were required longer time for emergency personnel activities. J Japanese Soc Emerg Med 2010;13:303–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platts-Mills TF, Leacock B, Cabañas JG et al. . Emergency medical services use by the elderly: analysis of a state database. Prehosp Emerg Care 2010;14:329–33. 10.3109/10903127.2010.481759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambulance Service Planning Office of Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan and Guidance of Medical Service Division, Health Policy Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan: a report on the acceptance of emergency patients by medical institutions. http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/houdou/h22/2203/220318_6houdou.pdf (accessed 3 Nov 2015).

- 13.Bucheli B, Martina B. Reduced length of stay in medical emergency department patients: a prospective controlled study on emergency physician staffing. Eur J Emerg Med 2004;11:29–34. 10.1097/00063110-200402000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donald KJ, Smith AN, Doherty S et al. . Effect of an on-site emergency physician in a rural emergency department at night. Rural Remote Health 2005;5:380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savage DW, Woolford DG, Weaver B et al. . Developing emergency department physician shift schedules optimized to meet patient demand. CJEM 2015;17:3–12. 10.2310/8000.2013.131224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modén B, Ohlsson H, Merlo J et al. . Risk factors for diagnosed intentional self-injury: a total population-based study. Eur J Public Health 2013;24:286–91. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durant E, Fahimi J. Factors associated with ambulance use among patients with low-acuity conditions. Prehosp Emerg Care 2012;16:329–37. 10.3109/10903127.2012.670688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowlton A, Weir BW, Hughes BS et al. . Patient demographic and health factors associated with frequent use of emergency medical services in a mid-sized city. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1101–11. 10.1111/acem.12253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doupe MB, Palatnick W, Day S et al. . Frequent users of emergency departments: developing standard definitions and defining prominent risk factors. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:24–32. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osaka Distinct Court: the court record of a case 2009 (wa) 5886. http://www.courts.go.jp/app/files/hanrei_jp/718/038718_hanrei.pdf (accessed 3 Nov 2015).

- 21.Osaka Prefecture: improvement plan of perinatal care system in Osaka. http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/iryo/syusankiiryo/ (accessed 3 Nov 2015).

- 22.Ambulance Service Planning Office of Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan: 2014 effect of first aid for emergency patients. The report about ways of emergency-medical-service. http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/about/shingi_kento/h25/kyukyu_arikata/pdf/houkokusyo.pdf (accessed 20 Nov 2015).