Abstract

Objectives

We compared 2 sociocultural cohorts with different duration of exposure to graphic health warning labels (GHWL), to investigate a possible desensitisation to their use. We further studied how a differing awareness and emotional impact of smoking-associated risks could be used to prevent this.

Setting

Structured interviews of patients from the general respiratory department were undertaken between 2012 and 2013 in 2 tertiary hospitals in Singapore and London.

Participants

266 participants were studied, 163 Londoners (35% smokers, 54% male, age 52±18 years) and 103 Singaporeans (53% smokers, p=0.003; 78% male, p<0.001; age 58±15 years, p=0.012).

Main outcomes and measures

50 items assessed demographics, smoking history, knowledge and the deterring impact of smoking-associated risks. After showing 10 GHWL, the impact on emotional response, cognitive processing and intended smoking behaviour was recorded.

Results

Singaporeans scored lower than the Londoners across all label processing constructs, and this was consistent for the smoking and non-smoking groups. Londoners experienced more ‘disgust’ and felt GHWL were more effective at preventing initiation of, or quitting, smoking. Singaporeans had a lower awareness of lung cancer (82% vs 96%, p<0.001), despite ranking it as the most deterring consequence of smoking. Overall, ‘blindness’ was the least known potential risk (28%), despite being ranked as more deterring than ‘stroke’ and ‘oral cancer’ in all participants.

Conclusions

The length of exposure to GHWL impacts on the effectiveness. However, acknowledging the different levels of awareness and emotional impact of smoking-associated risks within different sociocultural cohorts could be used to maintain their impact.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, tobacco control, psychology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cross-sectional cohort studies demonstrate associations and cannot be used to wholly determine causality.

Demographic differences between the London and Singapore cohorts.

Linear regression analysis showed that the primary outcome of ‘desensitisation’ was independent of other demographic variables, including ethnicity.

Participants were recruited from outpatient settings and the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Smoking remains a global public health issue with a total prevalence of 21%. Thirty-six per cent of men and 7% of women currently smoke.1 It is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in almost every country in the world,2 causing over six million deaths per year and accounting for 16% of all-cause mortality in men and 7% in women globally.3 In addition, the use of e-cigarette products and advertisements is currently on the rise.4 In recognition of the global epidemic of tobacco use, the WHO instigated the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and the 168 adopting countries were obliged to introduce ‘large, clear, visible and legible’ health warnings on cigarette packages.5

Cigarette packets remain a powerful marketing tool for the tobacco industry, creating brand awareness and influencing views on safety and perception of taste.6 Tobacco companies are predicted to spend more money on e-cigarette advertising in 2 days than the current total US annual budget on smoking and tobacco cessation education.7 Graphic health warning labels (GHWL) are pictorial graphic images that appear on the front of cigarette packages. They depict advanced stages of specific diseases, with accompanying messages, and can be used to educate the public, serving as healthcare advice to impact on smoking prevention and cessation8 both in smokers and non-smokers alike.9

GHWL have several advantages over text-only labels;9–14 they increase viewing time, attention, as well as the recall of messages,15 and they increase intention and motivation to quit smoking.11 13 They can also modify health beliefs about the dangers of smoking,16 17 and recent studies have shown that they are more effective in reducing cravings to smoke, particularly among adolescent smokers.18 19

In 2004, Singapore had become the first country in Asia to introduce GHWL,20 prior to the implementation of the FCTC. In 2008, the UK was the first European country to introduce GHWL on all tobacco packaging as a direct result of the European Commission labelling directive.21

This study aimed to investigate whether an increased duration of exposure to GHWL leads to a desensitisation of their impact, hypothesising a reduction in the cognitive processing domain. A number of studies until now have explicitly investigated a habituation to cigarette warning labels over time;22–25 however, none have explored this relation in the context of different cultural cohorts. Understanding cultural differences in their responses to specific labels, and using these differences, may prove an effective way to prevent desensitisation.

Patients and methods

Data were acquired at Guy's and St Thomas' National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, London, UK and at Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, during a 1-year period starting January 2012. Participants were recruited from respiratory department outpatient clinics within both hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We included male and female smokers and non-smokers who could communicate fluently and were aged between 21 and 80 years. Patients who were unable to consent, view the GHWL or understand the survey were excluded from the study.

In both countries, participants answered the questions in English, but Chinese-only speaking participants had the questions translated. Ex-smokers who had quit within the past 2 years were excluded from the analysis to allow a better comparison between smokers and non-smokers. At the time of the study, participants in Singapore had been exposed to GHWL for 8 years, twice as long as the London cohort (4 years). Some of the data on the London cohort, comparing smokers with non-smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), had been published in parts elsewhere.26

Structured survey

A structured survey containing 50 items based on previous studies was used for this study.26–29 The items were generated following an internal peer review among two tertiary hospitals (Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital, London, UK; and Singapore General Hospital, Singapore), and the Academic Health Sciences Centre (King's Health Partners, London, UK) with its associated academic institution (King's College London, UK).

The survey recorded demographics, smoking history and the perceived impact of smoking on health on a continuous scale from 1 (no effect) to 10 (maximum effect). It also recorded knowledge of specific smoking-associated health risks: ‘Do you believe the following diseases are related to smoking? (yes/no/not sure): “mouth and throat cancer”, “lung cancer”, “heart disease”, “stroke” and “blindness”’. The deterring impact for each risk was assessed by asking participants which disease they would ‘prevent’, if they could only choose one; and which they would ‘treat’, if only one could be treated.

Participants were then shown 10 UK and Singapore GHWL with similar messages, consisting of: ‘oral cancer’, ‘neck cancer’, ‘mouth disease’, ‘lung cancer’, ‘lung disease’, ‘heart attack’, ‘heart disease’, ‘stroke’, ‘miscarriage’ and ‘harms the baby’. After viewing the labels, the participants' emotional response to the labels was recorded by asking them to state whether they felt ‘fear’, ‘disgust’ or whether they ‘avoided looking at the labels’ (yes/no).

Participants' processing of the warning labels was also recorded regarding (1) package processing and (2) general processing (on a scale of 1 ‘not at all/never’ to 5 ‘all the time/a lot’).

Sample size analysis

A sample size calculation revealed that at least 200 participants were required, with 50 participants needed in each group of the study (smokers and non-smokers, in both cities) to achieve a power of >0.8, based on a 95% CI and an α of 0.05. The estimated label processing difference, measured from 1 ‘not at all/never’ to 5 ‘all the time/a lot’, was 1 out of 5 between the non-smoker groups (least expected difference compared with the smoker groups), with a maximum estimated population variance of 3–4, assumed to be the same in both cities.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected using MS Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, Washington, USA) and analysed with SPSS statistics V.22 (IBM, New York, New York, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess data for normality. Normally distributed categorical data were assessed using the χ2 test, and unpaired t-tests for non-categorical data. Non-normally distributed data were assessed using Spearman's coefficient, Mann-Whitney and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Where multiple correlations were found to be associated with the main outcome measures of knowledge score (ie, the number of risks that each participant was aware of), emotional response and depth of processing of the health warnings, multiple linear regression analyses were applied to determine independent factorial associations. The independent variables included in the regression analysis were age, gender, sex, ethnicity, smoking and city status (London vs Singapore). A level of significance was defined as a p<0.05.

Results

Demographics

A total of 266 participants were included in the study, 163 from London and 103 from Singapore. Participants from Singapore were predominantly ‘Chinese’ (71%) or ‘Asian/Asian other’ (27%) which includes people of Indian and Malay ethnicities. London respondents were predominantly ‘white’ (79%), ‘Asian/Asian British’ (10%) and ‘black/black British’ (9%). The London group was younger, with more male participants and a lower percentage of smokers. The ethnic background was different between the two groups, but typical of the two cities (table 1). The participants were matched for age (p=0.147) when comparing the smoking groups. The non-smoking groups were matched with regard to percentage of ex-smokers: 19 (40%) in Singapore, versus 41 (37%) in London (p=0.915; refer to online supplementary tables E1 and E2 for more detailed information on smoker and non-smoker demographic).

Table 1.

Demographic data of participants

| Total (n=266) | London (n=163) | Singapore (n=103) | χ2/one-way ANOVA (p value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 54.4 (16.8) | 52.4 (17.9) | 57.7 (14.5) | 0.012 |

| Male, n (%) | 168 (63) | 88 (54) | 80 (78) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 98 (38) | 75 (46) | 23 (22) | |

| Smokers, n (%) | 112 (42) | 57 (35) | 55 (53) | 0.003 |

| Chinese | 73 (27) | 0 (0) | 73 (71) | <0.001 |

| White | 129 (48) | 129 (79) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Asian/Asian other | 45 (17) | 17 (10) | 28 (27) | <0.001 |

| Black/black other | 14 (5) | 14 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.002 |

| Mixed | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.953 |

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

bmjopen-2016-012693supp_tables.pdf (282.2KB, pdf)

Perceived effect of smoking on health

Overall, non-smokers perceived smoking as more harmful than smokers (8.6±2.2 vs 7.7±2.4 points, p=0.001), while Londoners felt that smoking was more harmful than Singaporeans (8.8±1.7 vs 7.2±2.8 points, p<0.001), which was reflected in the results of the smokers (8.4±1.8 vs 6.9±2.7 points, p<0.001) and non-smoker groups (9.1±1.7 vs 7.6±2.9 points, p<0.012).

Awareness of health risks associated with smoking

Participants had the lowest awareness of the association between smoking and ‘blindness’, and were most aware of ‘lung cancer’ as a risk, followed by ‘mouth and throat cancer’, ‘heart disease’ and ‘stroke’. Smokers in Singapore were more aware of ‘blindness’ than smokers in London (p=0.031). Non-smokers in Singapore were less aware of ‘mouth and throat cancer’ and ‘lung cancer’ as a consequence of smoking than non-smokers in London (table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of participants showing awareness of smoking consequences: London (L) and Singapore (S), by smoking status

| All |

Non-smokers |

Smokers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | S | p Value | L | S | p Value | L | S | p Value | |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 138 (85) | 76 (74) | 0.029 | 86 (81) | 33 (70) | 0.134 | 51 (89) | 43 (78) | 0.104 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 116 (71) | 66 (64) | 0.226 | 73 (69) | 29 (62) | 0.386 | 42 (74) | 37 (67) | 0.457 |

| Blindness, n (%) | 39 (24) | 35 (34) | 0.075 | 26 (25) | 12 (26) | 0.895 | 13 (23) | 23 (42) | 0.031 |

| Mouth and throat cancer, n (%) | 147 (90) | 79 (77) | 0.003 | 97 (92) | 36 (77) | 0.012 | 49 (86) | 43 (78) | 0.282 |

| Lung cancer, n (%) | 156 (96) | 84 (82) | <0.001 | 102 (96) | 36 (77) | <0.001 | 53 (93) | 48 (87) | 0.310 |

Bold typeface denotes statistical significance.

Ethnicity was correlated with the total knowledge score of the smoking-related diseases (see online supplementary table E3), with Chinese participants being better informed overall than Caucasian participants (see online supplementary table E4); however, regression analyses showed that the significant differences in overall knowledge score between both cities were independent of the different ethnicity levels, age, gender, occupation and the levels of smokers and non-smokers in those cities (table 3).

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis of independent variables (country, age, gender, ethnicity, occupation and smoking status) on the main outcome measures: awareness of smoking risks, emotional response to and processing of graphic health warning labels

| Standardised coefficients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Knowledge |

Emotional response: ‘disgust’ |

Depth of processing |

||||||

| Model | β | t | Significance | β | t | Significance | β | t | Significance |

| Constant β (SE) | −1.538 (0.935) | −1.645 | 0.101 | 0.986 (0.211) | 4.662 | 0.000 | 18.933 (2.304) | 8.216 | 0.000 |

| Country | 0.464 | 7.558 | 0.000 | −0.250 | −3.703 | 0.000 | −0.289 | −4.448 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.003 | −0.054 | 0.957 | −0.013 | −0.192 | 0.848 | −0.112 | −1.827 | 0.069 |

| Gender | 0.044 | 0.752 | 0.453 | 0.022 | 0.349 | 0.728 | 0.025 | 0.466 | 0.642 |

| Ethnicity | 0.093 | 1.504 | 0.134 | 0.010 | 0.149 | 0.881 | −0.023 | −0.372 | 0.710 |

| Occupation | 0.063 | 1.074 | 0.284 | −0.038 | −0.586 | 0.558 | −0.036 | −0.631 | 0.529 |

| Smoking status | 0.095 | 1.680 | 0.094 | 0.032 | 0.514 | 0.607 | 0.36 | −1.513 | 0.132 |

Deterrent impact of smoking-associated risks

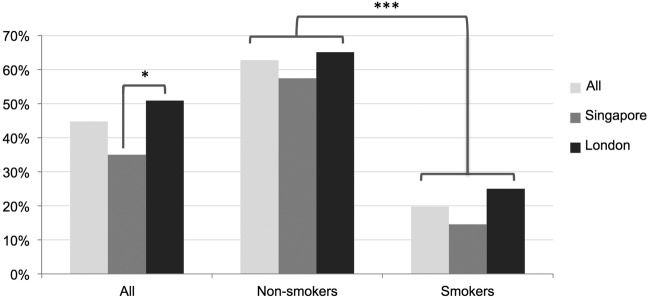

When participants were asked to choose one of the listed diseases that they could prevent or treat, ‘lung cancer’ was the most common choice, followed by ‘heart disease’, ‘blindness’, ‘stroke’ and ‘mouth and throat cancer’. Among smokers, ‘blindness’ ranked second behind ‘lung cancer’. Londoners, overall, chose ‘mouth and throat cancer’ more so than Singaporeans, and non-smokers in London were more likely to select ‘blindness’. In Singapore, smokers were more likely to select ‘stroke’ and non-smokers to choose ‘lung cancer’ (table 4). Overall, 45% of respondents felt that GHWL were a sufficient motivation to quit, or prevent from starting smoking, with more Londoners and more non-smokers in agreement (figure 1).

Table 4.

Combined percentage of participants who chose to prevent and treat each health risk when only one could be chosen: London (L) versus Singapore (S) overall, and by smoking statushttp://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012693

| All |

Non-smokers |

Smokers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | L | p Value | S | L | p Value | S | L | p Value | |

| Heart disease (%) | 18 | 22 | 0.251 | 19 | 25 | 0.301 | 17 | 18 | 0.957 |

| Stroke (%) | 12 | 7 | 0.046 | 12 | 9 | 0.544 | 13 | 3 | 0.004 |

| Blindness (%) | 13 | 18 | 0.111 | 6 | 17 | 0.013 | 18 | 19 | 0.831 |

| Mouth and throat cancer (%) | 1 | 9 | <0.001 | 0 | 9 | <0.001 | 2 | 7 | 0.060 |

| Lung cancer (%) | 50 | 43 | 0.103 | 61 | 39 | <0.001 | 41 | 50 | 0.172 |

Bold typeface denotes statistical significance. The individual ‘prevent only one’ and ‘treat only one’ table is available in the online supplementary table E5.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants (%) who felt graphic health warning labels are sufficient motivation to help them stop/not start smoking. Comparing London and Singapore and non-smokers with smokers in each city. *p≤0.05, ***p≤0.001.

Emotional response to GHWL

Following exposure to GHWL, 52% of all participants said that they experienced ‘fear’, 69% felt ‘disgust’ and 29% said they would avoid looking at the labels. Londoners, overall, were more likely to experience ‘disgust’ than Singaporeans, and this was consistent when comparing both smokers and non-smokers. There were no differences in the experience of ‘fear’ or ‘avoidance’ (table 5).

Table 5.

Percentage of participants who had an emotional reaction after viewing the graphic warning labels: London (L) and Singapore (S) overall, and by smoking status

| All |

Non-smokers |

Smokers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response n (%) | S | L | p Value | S | L | p Value | S | L | p Value |

| Experienced fear | 50 (49%) | 87 (53%) | 0.443 | 30 (64%) | 65 (61%) | 0.768 | 19 (35%) | 22 (39%) | 0.656 |

| Experienced disgust | 55 (53%) | 128 (79%) | <0.001 | 30 (64%) | 84 (79%) | 0.044 | 45 (45%) | 43 (75%) | 0.001 |

| Avoiding looking at labels | 29 (28%) | 47 (29%) | 0.905 | 13 (28%) | 28 (26%) | 0.873 | 16 (29%) | 18 (32%) | 0.775 |

Bold typeface denotes statistical significance.

While the feeling of ‘disgust’ was greater in specific ethnic groups (see online supplementary table E3), regression analyses revealed that the significant difference in ‘disgust’ between London and Singapore was independent of the ethnic make-up of both cities, in addition to age, gender, occupation, and the levels of smokers and non-smokers in each country (table 3). Overall, more non-smokers experienced ‘fear’ and ‘disgust’ than smokers (see online supplementary table E6 for more detailed information).

Cognitive processing of GHWL

Smokers and non-smokers in London showed a higher degree of label processing compared with their Singaporean counterparts (table 6). Overall, non-smokers talked more about GHWL than smokers, but no other significant differences in processing were found between them (refer to online supplementary table E7 for more detailed information).

Table 6.

Mean processing scores of graphic health warning labels (GHWL): comparing London (L) and Singapore (S) overall, and by smoking status

| All |

Non-smokers |

Smokers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing (/5) mean (95% CI) | S | L | p Value | S | L | p Value | S | L | p Value |

| How carefully do you read GHWL messages? | 1.80 (0.22) | 2.23 (0.19) | 0.004 | 1.64 (0.28) | 2.12 (0.25) | 0.024 | 1.95 (0.32) | 2.42 (0.30) | 0.028 |

| How often do you read GHWL messages? | 1.72 (0.21) | 2.25 (0.20) | <0.001 | 1.51 (0.25) | 2.24 (0.54) | 0.001 | 1.91 (0.33) | 2.27 (0.28) | 0.095 |

| How often have you thought about GHWL messages? | 1.64 (0.20) | 2.44 (0.21) | <0.001 | 1.51 (0.26) | 2.48 (0.27) | 0.001 | 1.76 (0.30) | 2.39 (0.34) | 0.006 |

| Have you ever talked about GHWL? | 1.52 (0.22) | 2.20 (0.21) | <0.001 | 1.55 (0.32) | 2.32 (0.28) | 0.001 | 1.53 (0.32) | 1.98 (0.27) | 0.039 |

| Have you ever thought about GHWL when they are not in sight (/5)? | 1.28 (0.14) | 1.77 (0.18) | <0.001 | 1.15 (0.17) | 1.77 (0.24) | 0.001 | 1.40 (0.23) | 1.76 (0.27) | 0.040 |

| Have you ever kept a GHWL (/5)? | 1.02 (0.04) | 1.25 (0.13) | 0.005 | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.26 (0.17) | 0.049 | 1.04 (0.07) | 1.25 (0.27) | 0.045 |

Bold typeface denotes statistical significance.

Discussion

This is the first study comparing the effect of GHWL across different cultures, Singapore versus London, and revealing a desensitisation effect to GHWL over time, as defined by diminished cognitive processing. Cultural differences were found in the response to various GHWL. Though the FCTC appreciates the need to refresh labels,30 policies do not exist which recognise the importance of cultural differences to focus any label refresh in order to prevent desensitisation.

During the study, Singaporeans have had exposure to GHWL for twice as long as Londoners and they displayed less ‘disgust’ and decreased processing of the health messages. These findings were independent of differences in the ethnicity, gender differences, occupation status and the levels of smokers and non-smokers in each county.

Significant differences in label processing were also found between non-smokers in London and Singapore, stressing the importance of GHWL for opposing smoking within the entire population, not just smokers. Consequently, this implies that non-smokers are prone to the same desensitisation effects as smokers and these findings raise the question as to how GHWL efficacy is best maintained.

Clinical significance

Our findings are consistent with previous descriptions of an exposure–affect relationship with health advertisements31–33 and a prognosticated ‘wear out’ effect. White et al24 showed that the cognitive processing among adolescents diminishes after 5 years, while other studies have shown the impact of GHWL ‘wear out’ after around 3 years, with differences existing between cultures.25 34 Exposure to new messages is processed more extensively than to well-known messages.35 36 Increased confidence surrounding messages, which is expected with greater familiarity, is also known to foster heuristic models of cognitive processing37 38 and less systematic processing of labels.39 Similar observations have been described in patients with COPD,26 although COPD is associated with cognitive and psychological biases that favour diminished processing.29 40–44 This study, however, reaches the same conclusion by comparing two separate cohorts with different exposure to GHWL.

Knowledge of adverse consequences of smoking

Knowledge of smoking-associated risks varies widely. A study comparing 21 European countries found considerable differences in the awareness that heart conditions are associated with smoking.45 This study observed that Singaporeans were less aware of the association with ‘mouth and throat cancer’, ‘heart disease’ and ‘lung cancer’ than Londoners. One-fifth of Singaporeans were unaware of smoking being associated with lung cancer and it is noteworthy that the message that ‘smoking causes lung cancer’ was removed from Singaporean labels in 2005, with ‘smoking causes lung disease’ introduced in 2013.46 This observation indicates that public health campaigns can potentially have a significant impact on public awareness.

‘Blindness’ was the least well-known risk despite having the second most deterring effect in smokers, as previously shown.47 The European Commission only officially approved a new warning ‘smoking causes blindness’ in 2012. It will be placed on cigarette packaging in the UK in 2016; although Singapore has introduced this warning in 2013, a large proportion of countries around the world have not included ‘blindness’ as a message on their packaging.46

Limitations of study

This paper is quasi-clinical in nature, and though there was an inability to critically analyse the population in their context and cultural norms, its strength is that it allows us, and policymakers, to speculate regarding why groups are different, why not and how long they should expose specific populations to GHWL before refreshing them—questions that have not yet been asked. We observed a significant difference in label processing at 8 vs 4 years and encourage policymakers to review their guidelines with these questions in mind, at least every 4 years.

Data were collected by means of a cross-sectional structured survey and the results should not be generalised to the general population per se. Participants were recruited from outpatient hospital settings, and hence a selection bias may have further influenced generalisability. A number of warning labels were shown over a short period of time and this might have perpetuated the expected emotional response. In addition, while the emotional response and cognitive processing questions were simple and applicable to everyday life, they lacked evidence of reliability and validity.

The Singaporean participants were older and had a higher proportion of smokers compared with the London cohort. Increased age was associated with decreased depth of processing and ‘fear’, but not ‘disgust’ or ‘avoidance’. However, our outcomes remained consistent when comparing just the smoking groups between both cities, where Singaporean and London smokers were matched for age. Outcomes were also confirmed when comparing the non-smoker groups. Further, the regression analyses showed independent differences between Singapore and London in ‘disgust’ and ‘label processing’, irrespective of other demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, occupation and smoking status).

Except for age and smoking status, other cultural differences may not have been accounted for in our analysis; hence, a more in-depth cultural and social analysis may be required in future work. While cultural differences may impact on the emotional response to labels, they would not impact on cognitive processing of labels or the primary outcome of desensitisation.

Conclusion

Desensitisation appears to occur with an increased length of exposure to GHWL. Previous studies have also implicated a habituation to the initial impact of GHWL over a period of weeks22 and others have implicated a ‘wear out’ effect over years.23 24 In addition, while studies have also compared the effect of GHWL among different countries,25 to the best of our knowledge, none have directly investigated the sociocultural relevance of the impact of desensitisation.

Current interest resides in a move towards plain cigarette packaging which removes branding and other distractors from the core messages presented.48 Culturally tailored renewal of GHWL to avoid a waning impact could be considered to maintain long-term efficacy. Any such approach should take into account the sociocultural context of the targeted population by assessing pre-existing awareness of smoking risks, as well as the emotional impact of different GHWL. Finally, the length of exposure to warning labels should be considered when timing the launch of future public health interventions. Future research should focus on this desensitisation effect with longitudinal studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Culadeeban Ratneswaran at @Deeban8

Contributors: CR designed the study, adapted the research items, established and oversaw the London and Singapore research teams, obtained ethical approval, and wrote all parts of the paper. He is the first guarantor. BC collected and analysed the data, and made significant contribution to the analysis section. ML and ST made significant contribution to the data collection and literature review of the paper. AD guided the statistical analysis and analysis section of the paper. DA established the project in Singapore, oversaw the Singapore research team and critically reviewed the paper prior to submission. JS is the second guarantor. He established the London research arm, oversaw and safeguarded data collection, and guided, critically reviewed and redrafted all aspects of the manuscript. All authors confirmed the final draft prior to submission.

Funding: JS's contribution was partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. Open access for this article was funded by King's College London.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (12/NE/0013).

Data sharing statement: All data are displayed. For further information, please contact the lead author—CR (c.ratneswaran@gmail.com).

References

- 1.Mendis S. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014: World Health Organization (report number: 9789241564854), 2014. https://goo.gl/1UK96e (accessed 16 Oct 2016).

- 2.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD et al. . A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO global report: mortality attributable to tobacco. 2012. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/rep_mortality_attributable/en/

- 4.Nasr SZ, Sweet SC. Electronic cigarette use in middle and high school students triples from 2013 to 2014. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:276–8. 10.1164/rccm.201505-0898ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO Framework convention on tobacco control. Secondary WHO Framework convention on tobacco control. http://www.who.int/fctc/en/ (accessed 06 Aug 2016).

- 6.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK et al. . The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2002;11(Suppl 1):i73–80. 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crotty Alexander L, Fuster M, Montgrain P et al. . The need for more e-cigarette data: a call to action. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:275–6. 10.1164/rccm.201505-0915ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West R. Smoking cessation interventions. In: Britton J, ed.. Fifty years since smoking and health: progress, lessons and priorities for a smoke-free UK. UK: Royal College of Physicians, 2012:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control 2011;20:327–37. 10.1136/tc.2010.037630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardavas CI, Connolly G, Karamanolis K et al. . Adolescents perceived effectiveness of the proposed European graphic tobacco warning labels. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:212–17. 10.1093/eurpub/ckp015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A et al. . Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii19–25. 10.1136/tc.2005.012294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong GT, Hammond D, Jiang Y et al. . Perceptions of tobacco health warnings in China compared with picture and text-only health warnings from other countries: an experimental study. Tob Control 2010;19(Suppl 2):i69–77. 10.1136/tc.2010.036483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW et al. . Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control 2003;12:391–5. 10.1136/tc.12.4.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R et al. . Communicating risk to smokers: the impact of health warnings on cigarette packages. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strasser AA, Tang KZ, Romer D et al. . Graphic warning labels in cigarette advertisements: recall and viewing patterns. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:41–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borland R, Hill D. Initial impact of the new Australian tobacco health warnings on knowledge and beliefs. Tob Control 1997;6:317–25. 10.1136/tc.6.4.317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQueen A, Kreuter MW, Boyum S et al. . Reactions to FDA-proposed graphic warning labels affixed to US smokers’ cigarette packs. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:784–95. 10.1093/ntr/ntu339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N et al. . How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC Four-Country survey. Addiction 2009;104:669–75. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02508.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thrasher JF, Hammond D, Fong GT et al. . Smokers’ reactions to cigarette package warnings with graphic imagery and with only text: a comparison between Mexico and Canada. Salud Publica Mex 2007;49:S233 10.1590/S0036-36342007000800013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singapore Ministry of Health. Healthy living everyday: tobacco control. Ministry of Health budget initiatives 2015 media fact sheets. Press Room. https://goo.gl/2dGpP9 (accessed 16 Oct 2016).

- 21. European Commission. Commission Decision of 5 September 2003 on the use of colour photographs or other illustrations as health warnings on tobacco packages. Official Journal of the European Union 2003/641/EC. https://goo.gl/YpsyqW (accessed 16 Oct 2016).

- 22.Rooke S, Malouff J, Copeland J. Effects of repeated exposure to a graphic smoking warning image. Curr Psychol 2012;31:282–90. 10.1007/s12144-012-9147-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller CL, Hill DJ, Quester PG et al. . Impact on the Australian quitline of new graphic cigarette pack warnings including the quitline number. Tob Control 2009;18:235–7. 10.1136/tc.2008.028290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White V, Bariola E, Faulkner A et al. . Graphic health warnings on cigarette packs: how long before the effects on adolescents wear out? Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:776–83. 10.1093/ntr/ntu184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT et al. . Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control 2009;18:358–64. 10.1136/tc.2008.028043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratneswaran C, Chisnall B, Drakatos P et al. . A cross-sectional survey investigating the desensitisation of graphic health warning labels and their impact on smokers, non-smokers and patients with COPD in a London cohort. BMJ Open 2014;4: e004782 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng DHL, Roxburgh STD, Sanjay S et al. . Awareness of smoking risks and attitudes towards graphic health warning labels on cigarette packs: a cross-cultural study of two populations in Singapore and Scotland. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:864–8. 10.1038/eye.2009.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moradi P, Thornton J, Edwards R et al. . Teenagers’ perceptions of blindness related to smoking: a novel message to a vulnerable group. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:605–7. 10.1136/bjo.2006.108191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoth KF, Wamboldt FS, Bowler R et al. . Attributions about cause of illness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:465–72. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Guidelines for Implementation of Article 5. 3 Article 8 Article 11 and Article 13. World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blair MH. An empirical investigation of advertising wearin and wearout. J Advertising Res 2000;40:95–100. 10.2501/JAR-40-6-95-100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bornstein RF. Exposure and affect: overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychol Bull 1989;106:265 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strahan EJ, White K, Fong GT et al. . Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: a social psychological perspective. Tob Control 2002;11:183–90. 10.1136/tc.11.3.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R et al. . Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:202–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn Psychol 1973;5:207–32. 10.1016/0010-0285(73)90033-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyer RS Jr, Hartwick J. The role of information retrieval and conditional inference processes in belief formation and change. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 1980;13:241–84. 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60134-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohner G, Moskowitz GB, Chaiken S. The interplay of heuristic and systematic processing of social information. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 1995;6:33–68. 10.1080/14792779443000003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Chaiken S. The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. Dual Process Theories Soc Psychol 1999;15:73–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuckerman A, Chaiken S. A heuristic-systematic processing analysis of the effectiveness of product warning labels. Psychol Mark 1998;15:621 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fritzsche A, Watz H, Magnussen H et al. . Cognitive biases in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and depression—a pilot study. Br J Health Psychol 2013;18:827–43. 10.1111/bjhp.12025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rusanen M, Ngandu T, Laatikainen T et al. . Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma and the risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a population based CAIDE study. Curr Alzheimer Res 2013;10:549–55. 10.2174/1567205011310050011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez CH, Richardson CR, Han MK et al. . Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, and development of disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:1362–70. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-187OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Association with Mild Cognitive Impairment: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Mayo Clinic Proc 2013;88:1222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh B, Mielke MM, Parsaik AK et al. . A prospective study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk for mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:581–8. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Smith H et al. . Tobacco smoking in young adults from 21 European countries: association with attitudes and risk awareness. Addiction 1995;90:571–82. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb02192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammond D. Tobacco Labelling Resource Centre. Secondary Tobacco Labelling Resource Centre, 2015. http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/.Last accessed 06/08/2016

- 47.Bidwell G, Sahu A, Edwards R et al. . Perceptions of blindness related to smoking: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:945–8. 10.1038/sj.eye.6701955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Health Organization. World No Tobacco Day, 31 May 2016: Get ready for plain packaging, 2016. World Health Organization news releases. https://goo.gl/oMHm2P (accessed 16 Oct 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012693supp_tables.pdf (282.2KB, pdf)