Abstract

Aberrant DNA methylation has been implicated in prostate carcinogenesis. The one-carbon metabolism pathway and related metabolites determine cellular DNA methylation and thus is thought to play a pivotal role in PCa occurrence. This study aimed to investigate the contribution of genetic variants in one-carbon metabolism genes to prostate cancer (PCa) risk and the underlying biological mechanisms. In this hospital-based case-control study of 1817 PCa cases and 2026 cancer-free controls, we genotyped six polymorphisms in three one-carbon metabolism genes and assessed their association with the risk of PCa. We found two noncoding MTR variants, rs28372871 T > G and rs1131450 G > A, were independently associated with a significantly increased risk of PCa. The rs28372871 GG genotype (adjusted OR = 1.40, P = 0.004) and rs1131450 AA genotype (adjusted OR = 1.64, P = 0.007) exhibited 1.40-fold and 1.64-fold higher risk of PCa, respectively, compared with their respective homozygous wild-type genotypes. Further functional analyses revealed these two variants contribute to reducing MTR expression, elevating homocysteine and SAH levels, reducing methionine and SAM levels, increasing SAH/SAM ratio, and promoting the invasion of PCa cells in vitro. Collectively, our data suggest regulatory variants of the MTR gene significantly increase the PCa risk via decreasing methylation potential. These findings provide a novel molecular mechanism for the prostate carcinogenesis.

Prostate cancer (PCa) remains the most frequently occurring non-cutaneous solid malignancy in men from Western countries and represents the second leading cause of cancer-related death next to lung cancer1,2. The incidence of PCa in China, although lower than in developed countries, has increased remarkably partly due to the increasing life expectancy, dietary changes and Westernized lifestyle3. Recently, accumulated evidence suggests that genetic factors, such as genetic polymorphisms, may contribute to the etiology of PCa4,5,6.

Aberrant DNA methylation plays an essential role in prostatic tumorigenesis by stimulating proto-oncogenes and inactivating tumor suppressor genes7,8. Alteration of DNA methylation is often identified in PCa and is associated with PCa initiation by regulating gene expression and promoting chromosomal instability9,10,11. Several epigenetic mechanisms related to one-carbon metabolism involving DNA and histone methylation, DNA uracil misincorporation, and chromosomal rearrangements have been observed in PCa cells12,13. The one-carbon metabolism pathway is a complex network of interdependent reactions that facilitates the transfer of one-carbon units and ultimately provides various forms of precursors needed for DNA synthesis, repair and methylation. Numerous studies showed that one-carbon metabolism gene polymorphisms were associated with the balance of one-carbon metabolism and the genome-wide DNA methylation levels in breast cancer and colorectal cancer14,15,16,17. Moreover, our previous study identified several noncoding variants within one-carbon metabolism genes were able to impair the one-carbon metabolism balance and were associated with increased risk of birth defect18,19,20. However, whether those noncoding variants contributed to the occurrence of cancer remains unknown. Thus, investigating the roles of one-carbon metabolism gene variations in the cancer development is a topic of much current interest. Studies addressing the relationship between polymorphisms of one-carbon metabolism genes and the risk of various cancers, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer and malignant lymphoma, have yielded conflicting results21,22,23,24,25. Few studies have addressed the effects of one-carbon metabolism gene polymorphisms on the risk of PCa, and the results have been inconsistent4,5,6. Marchal and colleagues explored the association between polymorphisms of MTHFR (rs1801133, rs1801131), MTR (rs1805087) and MTRR (rs1801394) genes and risk of PCa in a Spain cohort and found MTHFR rs1801131 is clearly related to prostatic carcinogenesis6. Collin et al.4 investigated the effect of eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including MTHFR rs1801133, MTHFR rs1801131, MTR rs1805087, MTRR rs1801394, MTHFD1 rs2236225, SLC19A1/RFC1 rs1051266, SHMT1 rs1979277 and FOLH1 rs202676, on PCa risk in a meta-analysis and found no significant effects of any SNPs on susceptibility to PCa.

The accumulation of homocysteine causes elevated levels of its precursor S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), thus leading to aberrant DNA methyltransferase activity26,27,28,29,30. For this reason, the role of homocysteine removal gene polymorphisms in modulating the risk of PCa warrants further research. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there are few studies of the possible correlation between genetic variations in the noncoding region of one-carbon metabolism genes and PCa risk have been published. The aim of the present study was to investigate the contribution of functional non-coding variants to the risk of PCa in a large-scale hospital-based case-control study, including MTR rs28372871, MTR rs1131450, MTRR rs326119 and CBS rs285014418,19,20. Moreover, we assessed the effects of other extensively reported polymorphisms of genes in the one-carbon metabolism pathway, including MTR rs1805087 and MTRR rs18013944,6,31, on the risk of PCa in our cohort.

Results

Characteristics of the study subjects

The demographic characteristics of the entire cohort are displayed in Table 1. The cases and controls were matched well by age, with a mean age of 66.7 and 66.9, respectively (P = 0.437). There were no significant differences in the distribution of age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease between 1817 cases and 2026 controls. Among the case subjects, 605 (33.3%) patients were Gleason score ≥8, 586 (32.3%) patients had extracapsular extension, 352 (19.4%) patients had positive surgical margins and 154 (8.5%) patients had lymph node involvement.

Table 1. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of 1817 PCa patients and 2026 controls included in the study.

| Variables | Cases (n = 1817) | Controls (n = 2026) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 66.7 ± 7.2 | 66.9 ± 6.8 | 0.437 |

| BMI (Kg/m2), n (%) | 0.877 | ||

| <25 | 1308 (72.0) | 1463 (72.2) | |

| ≥25 | 509 (28.0) | 563 (27.8) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.424 | ||

| No | 1054 (58.0) | 1201 (59.3) | |

| Yes | 763 (42.0) | 825 (40.7) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.926 | ||

| No | 1636 (90.0) | 1826 (90.1) | |

| Yes | 181 (10.0) | 200 (9.9) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 0.631 | ||

| No | 1660 (91.4) | 1842 (90.9) | |

| Yes | 157 (8.6) | 184 (9.1) | |

| PSA (ng/mL), mean ± SD | 28.5 ± 1.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Gleason score, n (%) | |||

| ≤6 | 289 (15.9) | ||

| 7 | 923 (50.8) | ||

| ≥8 | 605 (33.3) | ||

| Pathological tumor stage, n (%) | |||

| T2 | 1231 (67.7) | ||

| T3a | 160 (8.8) | ||

| T3b | 426 (23.4) | ||

| Positive surgical margins, n (%) | 352 (19.4) | ||

| Lymph node involvement, n (%) | 154 (8.5) |

Association between one-carbon metabolism gene variants and PCa risk

The genotype frequencies and their associations with the risk of PCa are summarized in Table 2. The genotype frequencies among the controls were all in agreement with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) (all P > 0.05). The variants rs28372871, rs1131450 and rs1805087 within MTR, and rs326119 and rs1801394 within MTRR, were not in high linkage disequilibrium (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Significant differences in genotype distributions between cases and controls were observed for the non-coding MTR variants rs28372871 T > G (P = 3 × 10−4) and rs1131450 G > A (P = 2 × 10−4). The homozygous GG genotype of rs28372871 in the MTR gene promoter (crude OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.20–1.73, P = 3 × 10−4) and the homozygous AA genotype of rs1131450 in the 3′UTR of the MTR gene (crude OR = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.30–2.41, P = 2 × 10−4) were associated with a significantly increased risk of PCa compared with their respective homozygous wild-type genotypes. Furthermore, both the above-mentioned genotypes maintained their statistical significance in multivariate logistic regression analyses after adjusting for age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Compared with the homozygous wild-types, there was a 1.40-fold increased risk of PCa associated with the MTR rs28372871 GG genotype (adjusted OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.15–1.71, P = 0.004) and a 1.64-fold increased risk associated with the MTR rs1131450 AA genotype (adjusted OR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.17–2.31, P = 0.007). Nevertheless, we did not observe statistical evidence to support associations of the other SNPs with PCa risk (Table 2).

Table 2. Associations between genetic polymorphisms in homocysteine removal genes and PCa risk in Han Chinese men.

| Gene | SNP | Type | Genotype | Cases (n = 1817) | Controls (n = 2026) | PHWE | Crude OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95% CI)c | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTR | rs28372871 | Promoter | TT | 449 (24.7) | 579 (28.6) | 0.180 | 1.00 | 3 × 10-4 | 1.00 | |

| TG | 910 (50.1) | 1037 (51.2) | 1.13 (0.97–1.32) | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | ||||||

| GG | 458 (25.2) | 410 (20.2) | 1.44 (1.20–1.73) | 1.40 (1.15–1.71) | 0.004 | |||||

| Dominant model | 1.22 (1.06–1.73) | 0.007 | 1.20 (1.03–1.41) | 0.020 | ||||||

| Recessive model | 1.33 (1.14–1.55) | 2 × 10-4 | 1.29 (1.10–1.53) | 0.002 | ||||||

| Log-additive model | 1.20 (1.09–1.31) | 1 × 10-4 | 1.18 (1.07–1.30) | 0.001 | ||||||

| rs1131450 | 3'UTR | GG | 1045 (57.5) | 1267 (62.5) | 0.120 | 1.00 | 2 × 10-4 | 1.00 | ||

| GA | 664 (36.5) | 685 (33.8) | 1.18 (1.03–1.34) | 1.14 (0.98-1.32) | ||||||

| AA | 108 (5.9) | 74 (3.7) | 1.77 (1.30–2.41) | 1.64 (1.17–2.31) | 0.007 | |||||

| Dominant model | 1.23 (1.08–1.40) | 0.001 | 1.19 (1.03–1.37) | 0.017 | ||||||

| Recessive model | 1.67 (1.23–2.26) | 8 × 10-4 | 1.57 (1.12–2.20) | 0.009 | ||||||

| Log-additive model | 1.24 (1.11–1.38) | 1 × 10-4 | 1.20 (1.06–1.35) | 0.003 | ||||||

| rs1805087 | Nonsynonymous | AA | 1481 (81.5) | 1692 (83.5) | 0.960 | 1.00 | 0.182 | 1.00 | ||

| (Asp → Gly) | AG | 316 (17.4) | 319 (15.7) | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | 1.11 (0.92–1.34) | |||||

| GG | 20 (1.1) | 15 (0.7) | 1.52 (0.78–2.99) | 1.72 (0.83–3.53) | 0.190 | |||||

| Dominant model | 1.15 (0.97–1.36) | 0.102 | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | 0.160 | ||||||

| Recessive model | 1.49 (0.76–2.92) | 0.240 | 1.69 (0.82–3.47) | 0.150 | ||||||

| Log-additive model | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) | 0.074 | 1.15 (0.97–1.36) | 0.100 | ||||||

| MTRR | rs326119 | Intron-1 | AA | 896 (49.3) | 944 (46.6) | 0.880 | 1.00 | 0.220 | 1.00 | |

| AC | 757 (41.7) | 881 (43.5) | 0.91 (0.79–1.03) | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | ||||||

| CC | 164 (9.0) | 201 (9.9) | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) | 0.86 (0.67–1.10) | 0.310 | |||||

| Dominant model | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.092 | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | 0.140 | ||||||

| Recessive model | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) | 0.345 | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) | 0.390 | ||||||

| Log-additive model | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | 0.087 | 0.92 (0.83–1.03) | 0.130 | ||||||

| rs1801394 | Nonsynonymous | AA | 985 (54.2) | 1111 (54.8) | 0.420 | 1.00 | 0.831 | 1.00 | 0.89 | |

| (Ile → Met) | AG | 706 (38.9) | 769 (38.0) | 1.04 (0.91–1.18) | 0.99 (0.85–1.14) | |||||

| GG | 126 (6.9) | 146 (7.2) | 0.97 (0.76–1.25) | 0.93 (0.71–1.24) | ||||||

| Dominant model | 1.03 (0.90–1.16) | 0.697 | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 0.770 | ||||||

| Recessive model | 0.96 (0.75–1.23) | 0.743 | 0.94 (0.71–1.23) | 0.650 | ||||||

| Log-additive model | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.860 | 0.98 (0.87–1.09) | 0.670 | ||||||

| CBS | rs2850144 | Promoter | CC | 774 (42.6) | 844 (41.7) | 0.180 | 1.00 | 0.818 | 1.00 | 0.910 |

| CG | 803 (44.2) | 905 (44.7) | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) | 0.98 (0.84–1.14) | ||||||

| GG | 240 (13.2) | 277 (13.7) | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.96 (0.77–1.19) | ||||||

| Dominant model | 0.96 (0.85–1.09) | 0.556 | 0.97 (0.85–1.12) | 0.710 | ||||||

| Recessive model | 0.96 (0.80–1.16) | 0.674 | 0.97 (0.79–1.18) | 0.740 | ||||||

| Log-additive model | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 0.530 | 0.98 (0.88–1.08) | 0.670 | ||||||

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

HWEP value for the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test in control subjects.

aAdjusted for age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in multivariant logistic regression models.

Stratification analysis

Further stratified analyses were performed to investigate associations between the SNPs evaluated and PCa risk by recessive, dominant and log-additive genetic model, respectively (Table 3, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that the MTR rs28372871 GG genotype and rs1131450 AA genotype were associated with an increased risk of PCa, particularly in subgroups of Gleason score ≥8, positive extracapsular extension, positive seminal vesicle invasion and positive lymph node involvement in all three models, as supported by homogeneity tests (all P < 0.05). In addition, although increased risk was observed among subgroups of BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and lacking diabetes mellitus for patients carrying MTR rs28372871 GG genotype and among subgroups of age ≤68 years and without cardiovascular disease for those carrying MTR rs1131450 AA genotype in all three models, further homogeneity tests did not support any difference in the estimates of PCa risk between these strata.

Table 3. Stratified analysis for associations between genetic polymorphisms in homocysteine removal genes and PCa risk by recessive genetic model in Han Chinese men.

| Variables | rs28372871 (cases/controls) |

Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | P | Phom | rs1131450 (cases/controls) |

Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

P | Phom | rs1805087 (cases/controls) |

Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | P | Phom | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT/TG | GG | GG/GA | AA | AA/AG | GG | |||||||||||

| Age (yr), median | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤68 | 762/1031 | 253/274 | 1.21 (0.95–1.53) | 0.120 | 0.294 | 959/1260 | 56/45 | 1.77 (1.08–2.88) | 0.022 | 0.970 | 1006/1293 | 9/12 | 0.81 (0.29–2.23) | 0.680 | 0.115 | |

| >68 | 597/585 | 205/136 | 1.42 (1.04–1.96) | 0.028 | 750/692 | 52/29 | 1.53 (0.81–2.88) | 0.180 | 791/718 | 11/3 | 3.14 (0.73–13.49) | 0.110 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||||||||||

| <25 | 993/1166 | 315/297 | 1.22 (0.92–1.51) | 0.074 | 0.193 | 1233/1410 | 75/53 | 1.49 (0.99–2.22) | 0.053 | 0.768 | 1292/1452 | 16/11 | 1.79 (0.0.79–4.10) | 0.160 | 0.631 | |

| ≥25 | 366/450 | 143/113 | 1.47 (1.07–2.01) | 0.016 | 476/542 | 33/21 | 1.83 (0.97–3.45) | 0.061 | 505/559 | 4/4 | 1.30 (0.29–5.89) | 0.730 | ||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 801/954 | 253/247 | 1.14 (0.91–1.43) | 0.250 | 0.199 | 994/1160 | 60/41 | 1.51 (0.95–2.42) | 0.081 | 0.851 | 1045/1190 | 9/11 | 1.06 (0.39–2.87) | 0.920 | 0.113 | |

| Yes | 558/662 | 205/163 | 1.45 (1.11–1.90) | 0.006 | 715/792 | 48/33 | 1.50 (0.88–2.57) | 0.140 | 752/821 | 11/4 | 4.17 (1.10–15.83) | 0.026 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1224/1463 | 412/363 | 1.35 (1.13–1.61) | 9 × 10−4 | 0.425 | 1539/1760 | 97/66 | 1.55 (1.08–2.21) | 0.017 | 0.875 | 1620/1812 | 16/14 | 1.49 (0.69–3.23) | 0.320 | 0.997 | |

| Yes | 135/153 | 46/47 | 0.86 (0.48–1.54) | 0.620 | 170/192 | 11/8 | 2.38 (0.82–6.87) | 0.110 | 177/199 | 4/1 | 4.20 (0.27–64.20) | 0.290 | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1254/1467 | 406/375 | 1.21 (0.92–1.46) | 0.067 | 0.055 | 1558/1779 | 101/63 | 1.80 (1.26–2.58) | 0.001 | 0.078 | 1646/1827 | 14/15 | 1.10 (0.50–2.44) | 0.810 | 0.061 | |

| Yes | 105/149 | 52/35 | 2.32 (1.26–4.25) | 0.006 | 151/173 | 7/11 | 0.37 (0.10–1.36) | 0.120 | 151/184 | 6/0 | NA (0.00-NA) | 0.005 | ||||

| Gleason score | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤7 | 932/1616 | 280/410 | 1.13 (0.93–1.38) | 0.220 | 0.017 | 1153/1952 | 59/74 | 1.10 (0.73–1.66) | 0.660 | 0.037 | 1204/2011 | 8/15 | 1.05 (0.41–2.71) | 0.910 | 0.057 | |

| ≥8 | 427/1616 | 178/410 | 1.67 (1.31–2.14) | <0.0001 | 556/1952 | 49/74 | 2.83 (1.78–4.48) | <0.0001 | 593/2011 | 12/15 | 2.79 (1.13–6.87) | 0.028 | ||||

| Extracapsular extension | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 961/1616 | 270/410 | 1.03 (0.84–1.25) | 0.780 | <0.0001 | 1171/1952 | 60/74 | 1.20 (0.81–1.79) | 0.370 | 0.033 | 1218/2011 | 13/15 | 1.42 (0.64–3.17) | 0.390 | 0.835 | |

| Yes | 398/1616 | 188/410 | 2.08 (1.62–2.67) | <0.0001 | 538/1952 | 48/74 | 2.41 (1.51–3.87) | 3 × 10−4 | 579/2011 | 7/15 | 2.63 (0.86–8.05) | 0.099 | ||||

| Seminal vesicle invasion | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1074/1616 | 317/410 | 1.11 (0.92–1.34) | 0.260 | <0.0001 | 1321/1952 | 70/74 | 1.22 (0.83–1.79) | 0.310 | 0.022 | 1375/2011 | 16/15 | 1.78 (0.83–3.82) | 0.140 | 0.761 | |

| Yes | 285/1616 | 141/410 | 2.12 (1.60–2.82) | <0.001 | 388/1952 | 38/74 | 3.08 (1.83–5.18) | <0.0001 | 422/2011 | 4/15 | 1.51 (0.39–5.89) | 0.560 | ||||

| Positive surgical margin | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1094/1616 | 371/410 | 1.29 (1.08–1.54) | 0.006 | 0.837 | 1383/1952 | 82/74 | 1.51 (1.05–2.16) | 0.026 | 0.300 | 1450/2011 | 15/15 | 1.43 (0.67–3.09) | 0.360 | 0.601 | |

| Yes | 265/1616 | 87/410 | 1.29 (0.93–1.81) | 0.140 | 326/1952 | 26/74 | 1.79 (0.95–3.36) | 0.078 | 347/2011 | 5/15 | 3.09 (0.81–11.71) | 0.110 | ||||

| Lymph node involvement | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1259/1616 | 404/410 | 1.23 (1.04–1.47) | 0.017 | 0.007 | 1569/1952 | 94/74 | 1.45 (1.02–2.05) | 0.039 | 0.133 | 1644/2011 | 19/15 | 1.75 (0.85–3.64) | 0.130 | 0.198 | |

| Yes | 100/1616 | 54/410 | 1.96 (1.27–3.02) | 0.003 | 140/1952 | 14/74 | 3.02 (1.39–6.57) | 0.008 | 153/2011 | 1/15 | 1.93 (0.18–21.10) | 0.610 | ||||

| Variables | rs326119 (cases/controls) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | P | Phom | rs1801394 (cases/controls) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | P | Phom | rs2850144 (cases/controls) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | P | Phom | ||||

| AA/AC | CC | AA/AG | GG | CC/CG | GG | |||||||||||

| Age (yr), median | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤68 | 925/1181 | 90/124 | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 0.600 | 0.701 | 938/1205 | 77/100 | 0.99 (0.73–1.35) | 0.940 | 0.894 | 888/1140 | 127/165 | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) | 0.920 | 0.593 | |

| >68 | 728/644 | 74/77 | 0.82 (0.53–1.26) | 0.360 | 753/675 | 49/46 | 1.07 (0.63–1.80) | 0.810 | 689/609 | 113/112 | 0.91 (0.64–1.30) | 0.610 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||||||||||

| <25 | 1190/1319 | 118/144 | 0.89 (0.68–1.18) | 0.430 | 0.905 | 1215/1365 | 93/98 | 1.07 (0.78–1.48) | 0.660 | 0.197 | 1146/1275 | 162/188 | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) | 0.530 | 0.979 | |

| ≥25 | 463/506 | 46/57 | 0.91 (0.57–1.43) | 0.670 | 476/515 | 33/48 | 0.70 (0.42–1.16) | 0.160 | 431/474 | 78/89 | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | 0.710 | ||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 959/1067 | 95/134 | 0.77 (0.56–1.05) | 0.096 | 0.195 | 977/1122 | 77/79 | 1.17 (0.81–1.68) | 0.400 | 0.153 | 907/1033 | 147/168 | 0.96 (0.73–1.26) | 0.780 | 0.647 | |

| Yes | 694/758 | 67/69 | 1.30 (0.88–1.94) | 0.190 | 714/758 | 49/67 | 0.74 (0.47–1.18) | 0.200 | 670/716 | 93/109 | 0.95 (0.67–1.35) | 0.790 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1481/1641 | 155/185 | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) | 0.530 | 0.330 | 1519/1695 | 117/131 | 0.98 (0.74–1.31) | 0.910 | 0.339 | 1421/1573 | 215/253 | 0.93 (0.75–1.16) | 0.530 | 0.489 | |

| Yes | 172/184 | 9/16 | 0.33 (0.10–1.15) | 0.064 | 172/185 | 9/15 | 0.59 (0.20–1.74) | 0.330 | 156/176 | 25/24 | 1.66 (0.81–3.38) | 0.170 | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1512/1654 | 148/188 | 0.85 (0.66–1.09) | 0.200 | 0.177 | 1543/1712 | 117/130 | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 0.950 | 0.322 | 1441/1595 | 219/247 | 1.00 (0.80–1.24) | 0.990 | 0.509 | |

| Yes | 141/171 | 16/13 | 1.91 (0.73–4.99) | 0.190 | 148/168 | 9/16 | 0.52 (0.17–1.54) | 0.220 | 136/154 | 21/30 | 1.18 (0.55–2.50) | 0.670 | ||||

| Gleason score | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤7 | 1104/1825 | 108/201 | 0.97 (0.74–1.29) | 0.850 | 0.836 | 1126/1880 | 86/146 | 0.99 (0.72–1.36) | 0.970 | 0.744 | 1058/1749 | 154/277 | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) | 0.390 | 0.449 | |

| ≥8 | 549/1825 | 56/201 | 0.80 (0.55–1.16) | 0.230 | 565/1880 | 40/146 | 0.87 (0.57–1.34) | 0.530 | 519/1749 | 86/277 | 1.09 (0.80–1.49) | 0.570 | ||||

| Extracapsular extension | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1129/1825 | 102/201 | 0.83 (0.63–1.10) | 0.190 | 0.176 | 1146/1880 | 85/146 | 0.91 (0.67–1.25) | 0.570 | 0.951 | 1069/1749 | 162/277 | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) | 0.680 | 0.940 | |

| Yes | 524/1825 | 62/201 | 1.11 (0.78–1.59) | 0.560 | 545/1880 | 41/146 | 1.01 (0.66–1.55) | 0.970 | 508/1749 | 78/277 | 0.96 (0.70–1.32) | 0.810 | ||||

| Seminal vesicle invasion | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1271/1825 | 120/201 | 0.89 (0.68–1.16) | 0.370 | 0.351 | 1297/1880 | 94/146 | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) | 0.590 | 0.642 | 1208/1749 | 183/277 | 0.95 (0.76–1.19) | 0.650 | 0.917 | |

| Yes | 382/1825 | 44/201 | 1.00 (0.66–1.52) | 1.000 | 394/1880 | 32/146 | 1.05 (0.65–1.72) | 0.830 | 369/1749 | 57/277 | 0.99 (0.69–1.42) | 0.940 | ||||

| Positive surgical margin | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1339/1825 | 126/201 | 0.84 (0.65–1.09) | 0.200 | 0.257 | 1366/1880 | 99/146 | 0.89 (0.66–1.19) | 0.410 | 0.594 | 1266/1749 | 199/277 | 0.98 (0.79–1.21) | 0.830 | 0.389 | |

| Yes | 314/1825 | 38/201 | 1.13 (0.71–1.79) | 0.600 | 325/1880 | 27/146 | 1.28 (0.72–2.26) | 0.410 | 311/1749 | 41/277 | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.580 | ||||

| Lymph node involvement | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1519/1825 | 144/201 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) | 0.240 | 0.100 | 1551/1880 | 112/146 | 0.91 (0.68–1.20) | 0.500 | 0.310 | 1443/1749 | 220/277 | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 0.870 | 0.936 | |

| Yes | 134/1825 | 20/201 | 1.23 (0.66–2.26) | 0.520 | 140/1880 | 14/146 | 1.51 (0.75–3.06) | 0.260 | 134/1749 | 20/277 | 0.97 (0.54–1.74) | 0.930 | ||||

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

homP value for homogeneity test using the χ2-based Q-test.

aAdjusted for age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease in multivariant logistic regression models.

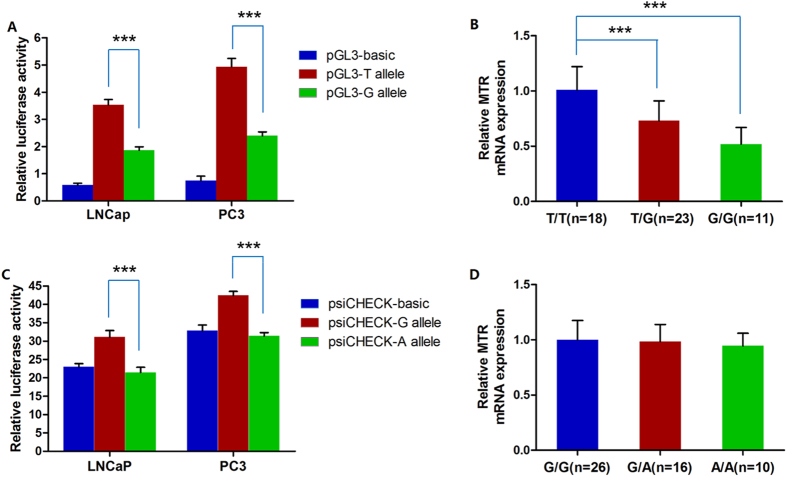

The promoter rs28372871 decreases MTR transcriptional activity in PCa cell lines and prostate tissues

Because the rs28372871 T > G variant is located in the core promoter region of the MTR gene, we speculated that it might influence MTR transcription. Thus, we carried out in vitro luciferase reporter assays in the PCa cell lines LNCaP and PC3 and compared mRNA levels among different genotypes of the rs28372871 T > G variant in 52 human prostate tissue samples to assess the functional consequence of variant rs28372871 T > G on MTR transcriptional activity. The luciferase assay revealed that a plasmid containing the minor G allele provided significantly lower luciferase expression in comparison with the major A allele with a 47.2% reduction in LNCaP cells and a 51.4% reduction in PC3 cells (Fig. 1A). Data from human prostate tissue showed that samples with the rs28372871 TG and GG genotypes displayed 27.7% and 48.5% reductions in MTR gene expression, respectively, compared with the TT genotype (Fig. 1B). These consistent findings confirmed our hypothesis that the promoter rs28372871 T > G variant functionally reduces the transcription of MTR.

Figure 1. The MTR variants rs28372871 T > G and rs1131450 G > A down-regulate MTR expression at the levels of transcription and translation, respectively.

(A) Luciferase expression is significantly decreased in the minor G allele construct compared with the major T construct in different cell types (47.2% reduction in LNCaP cells and 51.4% reduction in PC3 cells). (B) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of MTR in vivo mRNA expression in 52 human prostate tissue samples with different rs28372871 T > G genotypes. All values have been normalized to the level of GAPDH. (C) In luciferase assays, a plasmid construct with the minor A allele manifested luciferase activity significantly reduced by 31.1% compared with the major G allele in LNCaP cells. This value was 26.0% in PC3 cells. (D) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis of MTR in vivo mRNA expression in 52 human prostate tissue samples with different rs1131450 G > A genotypes. All values have been normalized to the level of GAPDH. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and each experiment was performed in triplicate. ***indicates P < 0.001.

The variant rs1131450 G > A reduces MTR expression

To investigate whether the rs1131450 G > A variant affects MTR expression, we performed in vitro luciferase reporter assays and assess the functional consequence of variant rs1131450 G > A on MTR transcriptional activity. The results of the transfection experiments showed that the plasmid construct carrying the mutant A allele manifested a 31.1% reduction in luciferase activity compared with that carrying the wild type G allele in LNCaP cells. There was a 26.0% reduction in PC3 cells (Fig. 1C). However, real-time PCR results showed that the variant rs1131450 was not related to MTR gene expression in human prostate tissue samples (Fig. 1D). Since the luciferase results indicated the protein level of target vector, these findings indicate that subjects carrying the MTR rs1131450 A allele might be at higher risk for PCa due to a reduction in MTR protein expression.

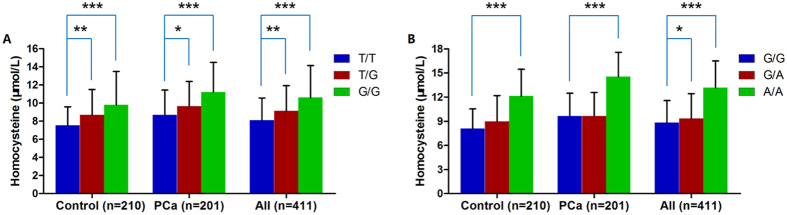

MTR variants correlate with human plasma homocysteine concentration

MTR is responsible for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, which is essential for maintaining normal homocysteine concentrations. Because the rs28372871 and rs1131450 variants could reduce MTR expression and be correlated with plasma homocysteine concentration in adolescence, we assumed that those variants also determine homocysteine levels in the PCa susceptible population. To test this hypothesis, we explored the relationship between the two variants and plasma homocysteine levels in 201 PCa patients and 210 matched control subjects. Our results regarding the rs28372871 T > G variant showed that the TG and GG genotypes were significantly associated with elevated plasma homocysteine levels compared with the wild-type TT genotype in PCa and control subgroups as well as in combined analysis (all P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). With regard to the rs1131450 G > A variant, carriers of the homozygous mutant AA genotype had the highest plasma homocysteine concentration, which was approximately 1.5-fold higher than those carrying the homozygous GG genotype in the PCa cohort, the control cohort and the entire cohort (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The functional MTR variants rs28372871 T > G and rs1131450 G > A correlate with human plasma homocysteine concentrations.

(A) Homocysteine concentrations were significantly different between the groups with different rs28372871 T > G genotypes in the PCa cohort, the control cohort and the entire cohort. (B) Homocysteine concentrations were significantly different between the groups with different rs1131450 G > A genotypes in the PCa cohort, the control cohort and the entire cohort. The data shown are expressed as the mean ± SD. *indicates P < 0.05, **indicates P < 0.01, ***indicates P < 0.001.

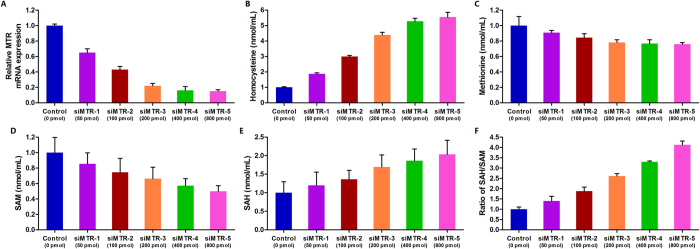

Down-regulation of MTR elevates cellular homocysteine and SAH levels and reduces methionine and SAM levels in PCa cell lines

Furthermore, we detected cellular homocysteine, methionine, SAM and SAH concentrations in PC3 and LNCaP cells after gradient transfection with MTR siRNA. The MTR knockdown efficiency and metabolites quantification in PC3 cells were shown in Fig. 3. The results of quantitative real-time PCR, which was performed to determine the knockdown efficiency, showed that the expression of MTR was down-regulated in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). We observed elevated cellular homocysteine levels and reduced methionine levels with decreasing MTR expression (Fig. 3B,C). Moreover, decreased SAM concentration, increased SAH concentration, and an increased SAH/SAM ratio were observed when MTR expression decreased (Fig. 3D–F). Results obtained in LNCaP cells were consistent with those in PC3 cells (Supplementary Figure 2). These findings suggested that reduced MTR expression led to increased homocysteine levels and reduced cellular methylation potential.

Figure 3. Down-regulation of MTR contributes to elevated cellular homocysteine and SAH levels, reduced methionine and SAM levels, and increased SAH/SAM ratio in PC3 cells.

(A) Knockdown efficiency of gradient MTR siRNA was measured using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. (B) Cellular homocysteine concentration after transfection with gradient MTR siRNA. (C) Cellular methionine level after transfected with gradient MTR siRNA. (D) Cellular SAM level after transfection with gradient MTR siRNA. (E) Cellular SAH level after transfection with gradient MTR siRNA. (F) Ratio of SAH/SAM after transfection with gradient MTR siRNA. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and each experiment was performed in triplicate.

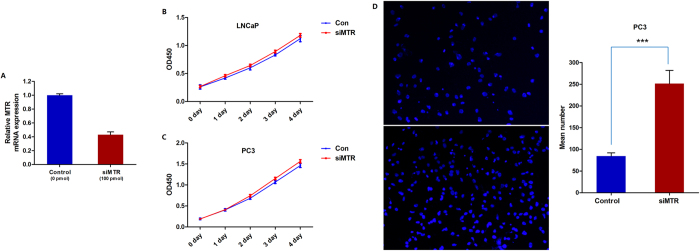

Down-regulation of MTR promotes cell invasion in vitro

Taking into consideration that the MTR genotype of risk led to nearly 50% reduction in MTR expression in vivo (Fig. 1B), LNCaP and PC3 cells with approximately 50% reduced MTR expression were constructed using siRNA (Fig. 4A). CCK-8 assays indicated that the approximately 50% reduction of MTR did not alter LNCaP or PC3 cell proliferation (Fig. 4B,C). However, in the PC3 cell invasion assay, we found that MTR knockdown significantly increased the number of invading cells following 24 hours of incubation compared with non-transfected cells (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4. Down-regulation of MTR significantly increased PCa cell invasion but did not alter cell proliferation in vitro.

(A) The knockdown efficiency of MTR siRNA was measured using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. (B) Down-regulation of MTR did not alter LNCaP cell proliferation. (C) Down-regulation of MTR did not alter PC3 cell proliferation. (D) Down-regulation of MTR significantly increased invasion by PC3 cells. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Discussion

In the current large-scale hospital-based case-control study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of a panel of genetic polymorphisms in 3 homocysteine removal genes involved in one-carbon metabolism and risk of PCa in 1817 cases and 2026 controls from an ethnic Han Chinese population. We found that two genetic variants in the regulatory regions of the MTR gene, rs28372871 T > G and rs1131450 G > A, were associated with a significantly increased risk of PCa. In previous study we proved that rs28372871 destroyed the transcription factor binding site in MTR promoter and rs1131450 enhanced the binding affinity of miRNA to the MTR 3′UTR18. In the current study, further functional analyses revealed that these two variants reduced the expression of the MTR gene in vitro and in vivo, elevated homocysteine and SAH levels, reduced methionine and SAM levels, increased the SAH/SAM ratio, and promoted the invasion of PCa cells in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between genetic variations in the noncoding region of one-carbon metabolism genes and risk of PCa.

MTR, one of the key enzymes in one-carbon metabolism, is responsible for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, thereby removing homocysteine. Consecutively, methionine is metabolized to yield SAM, which is the main methyl donor for methylation reactions. Studies addressing the relationship between MTR gene polymorphisms and risk of various cancers have yielded contradictory results. It was reported that MTR polymorphisms increase the risk of colorectal cancer21, breast cancer22, and malignant lymphoma23, but these findings have not been confirmed in other studies24,25. In a meta-analysis of one-carbon metabolism genes and risk of PCa, Collin et al. found that the MTR c.2756 A > G polymorphism was positively associated with PCa risk4. However, another study reported that there was no risk or statistically significant association between MTR polymorphism and PCa5. In the present study, we found that two noncoding MTR variants, rs28372871 T > G and rs1131450 905G > A, were independently associated with a significantly increased risk of PCa. The homozygous GG genotype of the variant rs28372871 in the promoter region (adjusted OR = 1.40, P = 0.004) and the homozygous AA genotype of the variant rs1131450 in the 3′UTR region (adjusted OR = 1.64, P = 0.007) exhibited a 1.40-fold and a 1.64-fold higher risk of PCa, respectively, compared with their respective homozygous wild-type genotypes in multivariate analyses. Furthermore, functional experiments revealed that both of the risk MTR allelic variants reduce MTR expression significantly. Decreased MTR expression results in elevated homocysteine levels with a simultaneous reduction of methionine production, consequently leading to an increased SAH/SAM ratio, which represents decreased methylation ability. Therefore, we inferred that the functional MTR variants rs28372871 and rs1131450 increase the risk of PCa via impairing methylation reactions considering that global DNA hypomethylation is a feature of prostatic tumorigenesis32,33,34.

MTRR catalyzes the regeneration of methylcobalamin, a cofactor of MTR, keeping MTR active. This is the first study to examine the association of the MTRR rs326119 polymorphism with the risk of PCa, and we report null results. Moreover, we did not observe an association between rs1801394, the most frequently studied MTRR polymorphism, and the risk of PCa. Previous studies that examined the MTRR rs1801394 polymorphism in relation to PCa risk generally showed null results, which is consistent with our results4,6.

CBS, as a rate-limiting enzyme, catalyzes the first irreversible step from homocysteine to cystathionine in the transsulfuration pathway. So far, few studies concerning the association between genetic polymorphisms in CBS and PCa risk have been published5. Kimura et al.5 investigated the association of CBS 844ins68 polymorphism and susceptibility to PCa and found no significant association. In this study, we found that the polymorphism rs2850144 C > G in the CBS gene promoter region was not associated with PCa risk. Recently, Zhang et al. observed an association between the CBS rs706209 polymorphism and clear cell renal cell carcinoma risk in the Chinese population35. Soon afterwards, Gallegos-Arreola and colleagues reported that the 844ins68 polymorphism in the CBS gene contributes significantly to breast cancer susceptibility in Mexican population36. Nevertheless, negative results have been observed with regard to different types of cancer37,38,39. Various factors, including differences in study design, study population and dietary assessment, could contribute to these inconsistent findings.

We acknowledge that there are certain limitations in the present study. Firstly, this hospital-based case-control study may have some selection and information biases, although these might be minimized by the age-matching between cases and controls as well as the adjustment for potential confounding factors in the statistical analyses. Secondly, although we investigated six SNPs in three key genes thought to be important in PCa risk in the one-carbon metabolism pathway, other potentially functional genetic variants may not have been included in the current study. Another potential limitation of this study is that the modest number of cases in the stratified analyses may limit the statistical power to examine the genetic variants with regard to the risk of PCa. Finally, the lack of data on folate intake and levels prohibits the evaluation of their effects on genetic variants in one-carbon metabolism genes and risk of PCa, thus limiting our conclusions. Notwithstanding these limitations, the results of the current study underscore that genetic variants in one-carbon metabolism genes may influence their function in one-carbon supply and subsequently result in elevated homocysteine levels and aberrant DNA methylation, thereby modifying PCa risk.

In summary, this large-scale hospital-based case-control study revealed that two functional variants in the regulatory regions of the MTR gene, rs28372871 T > G and rs1131450 G > A, were associated with a significantly increased risk of PCa by reducing MTR expression, elevating homocysteine and SAH levels, reducing methionine and SAM levels, increasing the SAH/SAM ratio, and promoting invasion by PCa cells. Our findings suggest that one-carbon metabolism plays a vital role in the etiology of PCa, and further investigation of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions in one-carbon metabolism is warranted.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This hospital-based case-control study recruited 1817 eligible patients with newly diagnosed PCa and 2026 matched cancer-free controls from genetically unrelated ethnic Han Chinese participants treated at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center from January 2008 to June 2015. All cases had histologically confirmed primary prostate adenocarcinoma assessed independently by two pathologists in routine diagnosis. All pathologic diagnoses were performed according to the WHO criteria for PCa. Cases who had malignancies other than primary PCa, had a family history of PCa and those who had radiotherapy or chemotherapy before enrollment were excluded. The tumor stage was determined and categorized according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM classification system40. Histopathological grading was performed according to the Gleason score system. Patient clinicopathological characteristics including age, height, weight, serum PSA level at diagnosis, characteristics at surgery (tumor grade, tumor stage, surgical margin status and lymph node involvement) and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease) were extracted from the archival medical records.

The 2026 male cancer-free control subjects were frequency-matched to cases by age and geographic area and were recruited during the same period. Due to population-based PCa screening using PSA and digital rectal examination not being a routine practice in China, those who suffered from low urinary tract symptoms were advised to have serum PSA testing and a digital rectal examination, and subjects with serum PSA > 4 ng/mL with or without an abnormal digital rectal examination were excluded from the control group. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration II and approved by the Institution Review Board of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before any study-specific investigation was performed.

SNP identification and genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral leukocytes by standard procedures using the Qiagen Blood DNA KIT (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). Polymorphisms in noncoding regions of the MTR (rs28372871, rs1131450), MTRR (rs326119) and CBS (rs2850144) genes were amplified by PCR. Selected SNPs, including polymorphisms in noncoding regions of the MTR, MTRR and CBS genes and the MTR rs1805087 and MTRR rs1801394 polymorphisms, were genotyped using SNaPshot analysis (ABI)18,19,20. Five percent of the genotyping results were validated using direct dye terminator sequencing of PCR products in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol of the ABI Prism BigDye system (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). The samples for sequencing and genotyping were run on an ABI 3730 automated sequencer and analyzed by SeqMan and Peakscan, respectively.

Cell lines and cell culture

Human LNCaP and PC3 cell lines (The Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai) were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). The cells were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37 °C and media was replaced every other day. Short tandem repeats genotyping and intermittent testing for androgen responsiveness (growth and androgen receptor activity) were performed to authenticate the cell lines. The genotypes of detected SNPs in these cell lines were detected and listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Plasmid construction and luciferase reporter assay

The luciferase reporter plasmids were constructed as described before18. Briefly, 1304 bp MTR fragments from −1267 to +37 containing either T allele or G allele of rs28372871 were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA. After digestion with MluI and BglII, the PCR products were subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), in which the firefly luciferase gene was used as a reporter. To construct the MTR 3′UTR reporter plasmid, 878 bp fragments of the 3′UTR of the MTR gene containing either the G allele or A allele of rs1131450 were amplified from genomic DNA. The PCR products were subsequently digested using XhoI and BamHI and cloned into the 3′UTR of the Renilla luciferase gene of the psiCHECK-2 vector (Promega). The Renilla luciferase gene was used as a reporter, and its expression could be normalized to the firefly luciferase signal. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

In luciferase reporter assay, 1 μg of each MTR reporter plasmid and 20 ng of the pRL-TK plasmid (Promega) as an internal control were transfected into LNCaP or PC3 cells. After 24 hours of transfection, cell lysates were collected and subjected to luciferase assay using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Each luciferase assay was performed in triplicate, and three independent transfection experiments were carried out.

Quantitative real-time PCR

We randomly collected 52 human prostate tissue samples from surgery of PCa patients and extracted total RNA using TransZol Up Plus Kit (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China). After the total RNA was converted to cDNA using random hexamers, oligo primers and reverse transcriptase (Takara), the MTR mRNA were quantified by real-time PCR using the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system with GAPDH as an internal control. Each reaction was performed in triplicate. The primers utilized are listed in supplementary Table 6.

siRNA transfection

MTR siRNA and mock siRNA negative control were chemically synthesized (Genepharma, Shanghai, China). For transfection, PC3 cells were seeded in six-well plates at 50–70% confluency. MTR siRNA was transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 48 hours after transfection, the cells were seeded for cell proliferation assays and invasion assays.

Plasma and cellular one-carbon metabolite quantification

EDTA-plasma samples were randomly collected from 201 PCa patients and 210 cancer-free control participants, centrifuged immediately and frozen at −80 °C for quantifying the homocysteine levels. Plasma homocysteine levels were determined using the Axis® Homocysteine Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) Kit (Axis-Shield, Norton, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PC3 cells were transfected with 0 pmol, 50 pmol, 100 pmol, 200 pmol, 400 pmol or 800 pmol of MTR siRNA. After 48 hours of transfection, the cells were harvested for the detection of metabolite levels. Cellular homocysteine levels were determined using the Axis® Homocysteine Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) Kit. The levels of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and SAH were detected with a SAM & SAH ELISA Combo Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). The concentration of methionine was quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously reported41. Each test was repeated in triplicate, and the mean level was used for further analysis.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation after transfection was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Briefly, LNCaP and PC3 cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After incubation for 48 hours, CCK-8 solution (10 μl) was added to each well and incubated in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 2 hours. Then, the absorbance of samples taken from each well was measured at 450 nm, on the basis of which the percentage of surviving cells in each treatment group was plotted relative to the untreated one.

Cell invasion assay

Cellular invasion was measured using a Transwell chamber (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after transfection, 1 × 105 PC3 cells suspended in 100 μl F-12K medium without fetal bovine serum were seeded in the upper chamber of Transwell inserts with a pore size of 8 μm. A volume of 600 μl F-12K medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum as a chemoattractant was added to the lower chamber. Subsequent to a 24 hour incubation, the Transwell insert was washed with PBS, and cells on the upper surface of the insert were gently removed with a cotton swab. Invading cells (lower surface of the insert) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min and were stained with DAPI. All assays were independently repeated in triplicate. Five random microscopic fields were evaluated for each insert.

Statistical analysis

Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and was categorized according to the WHO cut point for obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) in Asian populations42. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for evaluation of genotype distribution in the control subjects was calculated using the goodness-of fit χ2 test, and P < 0.05 was considered deviated from the equilibrium. Univariate and multivariate unconditional logistic regression models were used to calculate crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), respectively, to evaluate associations between the genotypes and PCa risk, with adjustments for age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in multivariate models. In addition, stratified analysis was performed to explore the association between the genotypes and risk of PCa among subgroups of age (≤68 vs. >68), BMI (<25 vs. ≥25), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, Gleason score, extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, positive surgical margin and lymph node involvement. In the stratified analysis by age, patients were grouped using the median age (68 years old) as cutoff. The Chi-square-based Q test was performed to detect the homogeneity of associations between subgroups. For all statistical tests, a two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Qu, Y.-Y. et al. Functional variants of the 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase gene significantly increase susceptibility to prostate cancer: Results from an ethnic Han Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 6, 36264; doi: 10.1038/srep36264 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the 863 Program (number 2015AA020913), the 973 Program (Number 2015CB943300), the National Science Foundation of China (Numbers 81471454 and 31521003), Commission for Science and Technology of Shanghai Municipality (Numbers 14ZR1402000 and 15XD1500500) to Zhao J.Y., grant from the National Science Foundation of China (Number 81472377) to Ye D.W. and grant from Shanghai rising star project (Number 16QA1401100) to Zhu Y.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.-Y.Q. acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. S.-X.Z., X.Z., R.Z., C.-Y.G. and K.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. X.-Q.Y. and H.-L.G. reviewed Haematoxylin and eosin sections to confirm tumor histology. B.D. and H.-L.Z. prepared all figures. G.-H.S. edited all tables. Y.Z., D.-W.Y. and J.-Y.Z. designed and supervised the study, and provided funding support. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

References

- Ferlay J. et al. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO 18, 581–592, doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D. & Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 65, 5–29, doi: 10.3322/caac.21254 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y. et al. Constitutively active AR-V7 plays an essential role in the development and progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Scientific reports 5, 7654, doi: 10.1038/srep07654 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin S. M. et al. Association of folate-pathway gene polymorphisms with the risk of prostate cancer: a population-based nested case-control study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 18, 2528–2539, doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0223 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F. et al. Methyl group metabolism gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to prostatic carcinoma. The Prostate 45, 225–231 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal C. et al. Association between polymorphisms of folate-metabolizing enzymes and risk of prostate cancer. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 34, 805–810, doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.09.008 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W. G., De Marzo A. M. & Isaacs W. B. Prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine 349, 366–381, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021562 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingg J. M. & Jones P. A. Genetic and epigenetic aspects of DNA methylation on genome expression, evolution, mutation and carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 18, 869–882 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Roles of Distal and Genic Methylation in the Development of Prostate Tumorigenesis Revealed by Genome-wide DNA Methylation Analysis. Scientific reports 6, 22051, doi: 10.1038/srep22051 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H. et al. Deep sequencing reveals distinct patterns of DNA methylation in prostate cancer. Genome research 21, 1028–1041, doi: 10.1101/gr.119347.110 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden A., Gaudet F., Waghmare A. & Jaenisch R. Chromosomal instability and tumors promoted by DNA hypomethylation. Science 300, 455, doi: 10.1126/science.1083557 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegnasubramanian S. et al. DNA hypomethylation arises later in prostate cancer progression than CpG island hypermethylation and contributes to metastatic tumor heterogeneity. Cancer research 68, 8954–8967, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6088 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bistulfi G., Vandette E., Matsui S. & Smiraglia D. J. Mild folate deficiency induces genetic and epigenetic instability and phenotype changes in prostate cancer cells. BMC biology 8, 6, doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-6 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra A. et al. Germline polymorphisms in the one-carbon metabolism pathway and DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer causes & control: CCC 21, 331–345, doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9464-2 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. A. et al. Genetic variation in one-carbon metabolism in relation to genome-wide DNA methylation in breast tissue from heathy women. Carcinogenesis, doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw030 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friso S. et al. The MTHFR 1298A > C polymorphism and genomic DNA methylation in human lymphocytes. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 14, 938–943, doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0601 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroo L. A. et al. Global DNA methylation and one-carbon metabolism gene polymorphisms and the risk of breast cancer in the Sister Study. Carcinogenesis 35, 333–338, doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt342 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. Y. et al. Genetic variants reducing MTR gene expression increase the risk of congenital heart disease in Han Chinese populations. European heart journal 35, 733–742, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht221 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. Y. et al. Functional variant in methionine synthase reductase intron-1 significantly increases the risk of congenital heart disease in the Han Chinese population. Circulation 125, 482–490, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050245 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. Y. et al. A functional variant in the cystathionine beta-synthase gene promoter significantly reduces congenital heart disease susceptibility in a Han Chinese population. Cell research, doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.135 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vogel S. et al. Genetic variants of methyl metabolizing enzymes and epigenetic regulators: associations with promoter CpG island hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 18, 3086–3096, doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0289 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cassia Carvalho Barbosa R., da Costa D. M., Cordeiro D. E., Vieira A. P.& Rabenhorst S. H. Interaction of MTHFR C677T and A1298C, and MTR A2756G gene polymorphisms in breast cancer risk in a population in Northeast Brazil. Anticancer research 32, 4805–4811 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K. et al. Association between polymorphisms of folate- and methionine-metabolizing enzymes and susceptibility to malignant lymphoma. Blood 97, 3205–3209 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. et al. No association between MTR rs1805087 A > G polymorphism and non-Hodgkin lymphoma susceptibility: evidence from 11 486 subjects. Leukemia & lymphoma 56, 763–767, doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.935370 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D., Mei Q., Luo H., Tang B. & Yu P. The polymorphisms in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, methionine synthase, methionine synthase reductase, and the risk of colorectal cancer. International journal of biological sciences 8, 819–830, doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill M. A. et al. Intracellular S-adenosylhomocysteine concentrations predict global DNA hypomethylation in tissues of methyl-deficient cystathionine beta-synthase heterozygous mice. The Journal of nutrition 131, 2811–2818 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer A. A. et al. LINE-1 DNA methylation is inversely correlated with cord plasma homocysteine in man: a preliminary study. Epigenetics 4, 394–398 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N. C. et al. Regulation of homocysteine metabolism and methylation in human and mouse tissues. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 24, 2804–2817, doi: 10.1096/fj.09-143651 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam F. et al. Homocysteine clearance and methylation flux rates in health and end-stage renal disease: association with S-adenosylhomocysteine. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 287, F215–F223, doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2003 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillemacher T., Frieling H., Muschler M. A. & Bleich S. Homocysteine and epigenetic DNA methylation: a biological model for depression? The American journal of psychiatry 164, 1610, doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060881 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. D. et al. Complex interaction between serum folate levels and genetic polymorphisms in folate pathway genes: biomarkers of prostate cancer aggressiveness. Genes & nutrition 8, 199–207, doi: 10.1007/s12263-012-0321-7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelic R. et al. Global DNA hypomethylation in prostate cancer development and progression: a systematic review. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases 18, 1–12, doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.45 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. A. Overview of cancer epigenetics. Seminars in hematology 42, S3–S8 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothman A. R. et al. Global hypomethylation is common in prostate cancer cells: a quantitative predictor for clinical outcome? Cancer genetics and cytogenetics 156, 31–36, doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.04.004 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. One-carbon metabolism pathway gene variants and risk of clear cell renal cell carcinoma in a Chinese population. PloS one 8, e81129, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081129 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos-Arreola M. P. et al. The association between the 844ins68 polymorphism in the CBS gene and breast cancer. Archives of medical science: AMS 10, 1214–1224, doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.47830 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbiatti A. L. et al. The association between CBS 844ins68 polymorphism and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma risk - a case-control analysis. Archives of medical science: AMS 6, 772–779, doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.17094 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A. S. et al. Polymorphisms in the folate-metabolizing genes MTR, MTRR, and CBS and breast cancer risk. Cancer epidemiology 36, e95–e100, doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.11.010 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. Genetic variations in the one-carbon metabolism pathway genes and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a case-control study. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine 36, 997–1002, doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2725-z (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Montironi R., Bostwick D. G., Lopez-Beltran A. & Berney D. M. Staging of prostate cancer. Histopathology 60, 87–117, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04025.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Tan Y., Yang Z., Li S. & Hoffman R. M. A rapid HPLC method for the measurement of ultra-low plasma methionine concentrations applicable to methionine depletion therapy. Anticancer research 25, 59–62 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consultation W. H. O. E. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 363, 157–163, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.