Abstract

We examined an immediate, but short-lived, response to crizotinib, a drug with a new indication for ROS1 rearranged non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in a middle-aged non-smoker. The patient presented with metastatic NSCLC and extensive disease in multiple organs. He was treated with crizotinib 250 mg twice a day. Within 2–3 days, his condition rapidly improved, which was evident in a CT scan 2 months later. However, after 3 months of treatment, his condition deteriorated dramatically. The patient did not respond to ceritinib, a second-line drug that targets anaplastic lymphoma kinase, and died shortly after. This case demonstrated an impressive but brief response to crizotinib.

Background

Crizotinib is a drug that targets anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and has been used successfully to treat patients with ALK mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1 The FDA approved the new indication of crizotinib for treatment of ROS1 rearranged NSCLC in March 2016.2 The ROS1 gene is found on chromosome 6q22 and codes for a tyrosine kinase; it shares a sequence homologue with ALK.3 ROS1 rearrangement is a rare mutation occurring in only 1–2% of all NSCLC patients.4 There are limited data regarding the use of crizotinib in this setting. Here we report a case of an immediate, but short-lived, response to crizotinib in a middle-aged non-smoker with an extremely aggressive NSCLC harbouring ROS1 rearrangements.

Case presentation

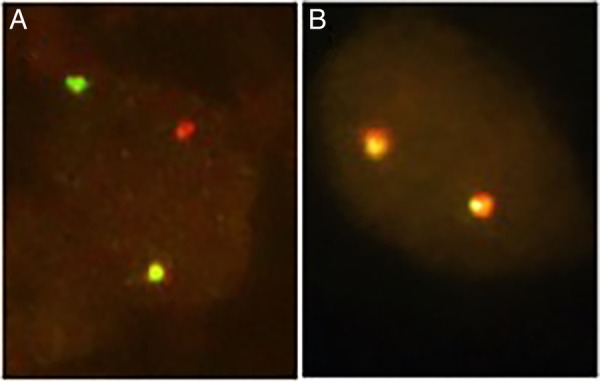

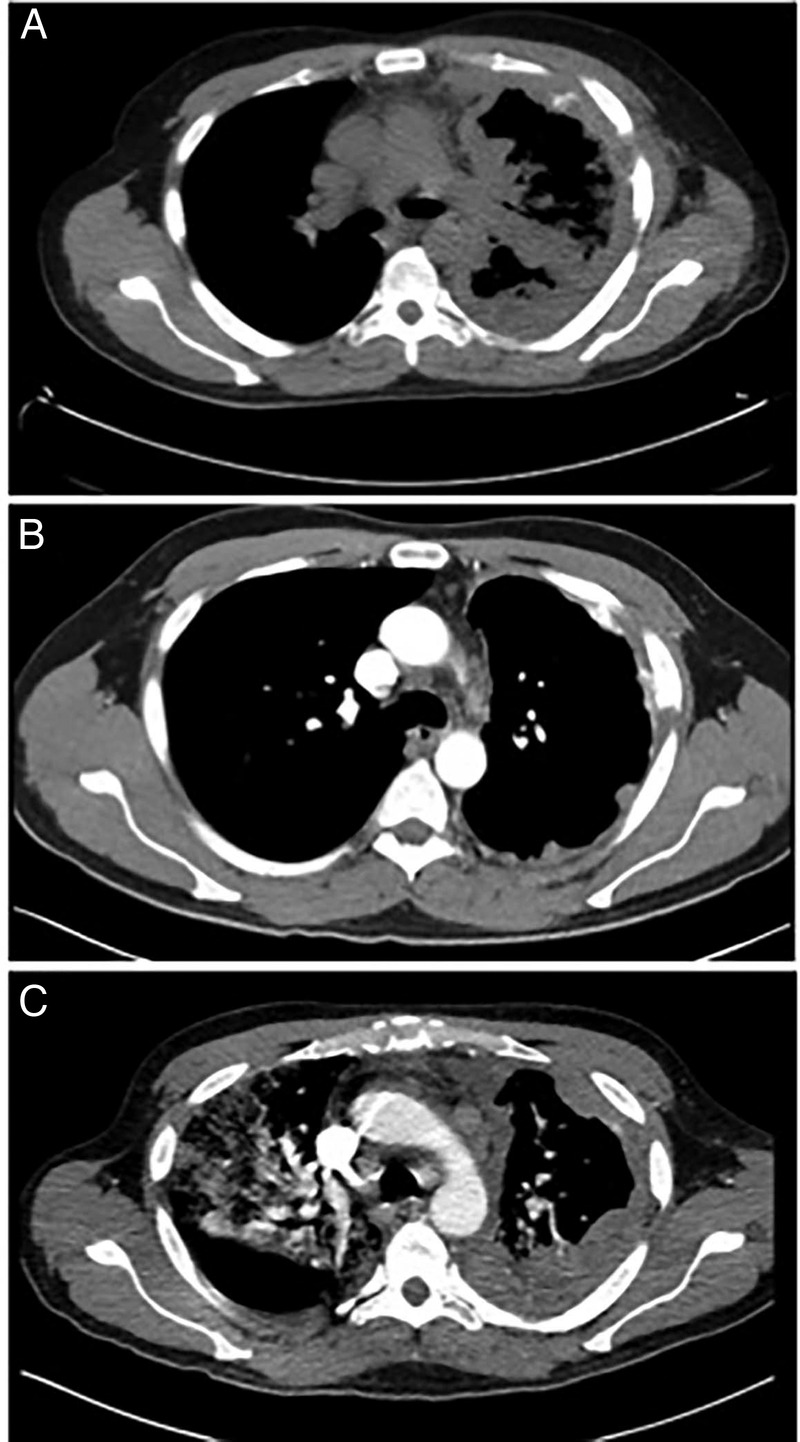

A middle-aged non-smoker and otherwise healthy man was admitted to the hospital for cough and shortness of breath. CT scans showed patchy infiltrates throughout the left lung and right lower lobe. In addition, there was enhancing irregular soft tissue at the left lung base, a potential sign for extensive loculated pleural effusion. He underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with pleural biopsy, which showed large cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumour cells were positive for TTF-1 and Napsin-A and negative for P40, P63 and CK5/6. These findings are consistent with solid-predominate type adenocarcinoma of the lung. Molecular analysis revealed that the tumour was negative for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations. Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) found evidence of XT ROS1 rearrangement (figure 1A) but no evidence of 2p23/ALK rearrangement (figure 1B). PET/CT scans performed 3 weeks later showed extensive disease in the left pleural space, left chest wall, lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm and numerous adrenal and osseous metastases (figure 2A). He was admitted to the hospital again for shortness of breath and possible pneumonia. Despite antibiotic treatment, he developed bilateral lower extremity oedema, abdominal distention and had trouble breathing and ambulating.

Figure 1.

Diagnosis of ROS1 rearrangement using FISH. (A) One yellow fusion, red and green sign demonstrate rearrangement for ROS 1 (×1000). (B) Two yellow fusion signs suggest no evidence of ALK rearrangement (×1000). ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation.

Figure 2.

(A) CT scans of the ROS1 rearrangement NSCLC patient before treatment with crizotinib. (B) Significant improvement is seen after 2 months of treatment. (C) Recurrence and progression of the disease is seen after 4 months of treatment. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Treatment

He was then started on crizotinib 250 mg twice a day.

Outcome and follow-up

His condition improved roughly 3 days after starting crizotinib. Within a week, his shortness of breath was alleviated, and he was discharged from the hospital without oxygen supplements. The patient felt energised and resumed routine activities. CT scans performed after 2 months of treatment showed significant improvements in pleural-based nodules, pleural effusion and in mediastinal and retroperitoneal nodes (figure 2B). However, after about 3 months on crizotinib, the patient developed lower back pain and rapidly progressive weakness in the lower extremities. MRI of the lumbar spine showed diffuse osseous metastases and near circumferential epidural metastases affecting the lateral recesses and neural foramina at L2–3, L3–4 and L4–5. He was treated with radiation and steroids without much improvement. Less than 4 months from the start of treatment, he was admitted into the hospital again due to shortness of breath and pneumonia-like symptoms. CT scans showed that the malignancy reappeared in the left lung, similar to the original CT scans; however, this time there was evidence of multiloculated pleural effusion (figure 2C). Furthermore, the scans showed multiple right pleural metastases (figure 2C). The patient was put on BiPAP with 100% oxygen and was treated for pneumonia without improvement. In the mean time, he was put on a second-line ALK rearrangement drug, ceritinib. However, the patient did not respond and died of respiratory failure less than a month after this hospitalisation and <6 months after the initial presentation of the disease. The autopsy identified a 16 cm hilar mass in the left upper and lower lobes, numerous right pleural metastases, measuring up to 0.3 cm in diameter, and numerous intra-abdominal metastases, including multiple liver and adrenal metastases.

Discussion

Lung cancer causes the most cancer-related deaths in men and women.5 Therapies that target EGFR, ALK and KRAS mutations now play pivotal roles in the treatment of NSCLC.1 ROS1 rearrangement is now being used as one of the newest targets for NSCLC.4 ALK and ROS1 share a significant amino acid sequence, making them both viable targets for crizotinib. Similar to ALK gene mutations, rearrangements of the ROS1 gene are often associated with younger and healthier patients, generally with no history of smoking.6

In this case report, our patient demonstrated a very rapid and significant response to crizotinib. However, the duration of our patient's response to crizotinib was <12 weeks, much shorter than the reported median response duration of 49.1 weeks.7 The shorter duration of response may be due to the unique biology of this patient's cancer, which exhibited a very aggressive nature. An extremely high tumour burden at the presentation of the disease could also have played a role in reducing the effectiveness of crizotinib. The sheer amount of malignant cells could have easily developed new mutations that caused resistance to crizotinib. Acquired resistance to crizotinib has been linked to new ROS1 mutations such as L2155S.8 Moreover, the expression of KRAS and EGFR has also been suggested to play a role in crizotinib resistance.3 9 Although these mutations are generally mutually exclusive at first, a case report by Rossing et al9 demonstrated that a patient on crizotinib developed resistance after 8 months of treatment due to new EGFR mutations. Studying the mechanisms behind acquired resistance is critical and may lead to the development of better second-line drugs. In conclusion, we found that crizotinib is a very effective medication for patients with ROS1 rearrangement; however, the rapid development of resistance poses a very serious problem that must be addressed.

Learning points.

ROS1 rearranged non-small cell lung cancer can behave aggressively.

Response to crizotinib in ROS1 rearranged cancer is very rapid and impressive.

Duration of response to crizotinib may be short, and the development of resistance to crizotinib is likely due to newly acquired mutations.

Second-line drug for ALK, ceritinib, was not very effective in this case. More effective second-line or third-line drugs are needed.

Footnotes

Contributors: EZ gathered data, drafted the article and performed the literature search. HH conceived the study and critically reviewed the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ou SH, Bartlett CH, Mino-Kenudson N et al. Crizotinib for the treatment of ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer: a success story to usher in the second decade of molecular targeted therapy in oncology. Oncologist 2012;17:1351–75. 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazandjian D, Blumenthal GM, Luo L et al. Benefit-risk summary of crizotinib for the treatment of patients with ROS1 alteration-positive, metastatic non-small cell lunc cancer. Oncologist 2016;21:974–80 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazières J, Zalcman Gérard Z, Crinò L et al. Crizotinib therapy for advanced lung adenocarcinoma and a ROS1 rearrangement: results from the EUROS1 cohort. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:992–9. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies KD, Le AT, Theodoro MF et al. Identifying and targeting ROS1 gene fusions in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4570–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Y, Zhang Y, Li Y et al. ALK, ROS1 and RET fusions in 1139 lung adenocarcinomas: a comprehensive study of common and fusion pattern-specific clinicopathologic, histologic and cytologic features. Lung Cancer 2014;84:121–6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw AT, Ou SH, Bang YJ et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1963–71. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song A, Kim TM, Kim DW et al. Molecular changes associated with acquired resistance to crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2379–87. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossing HH, Grauslund M, Urbanska EM et al. Concomitant occurrence of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) and KRAS (V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) mutations in an ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase)-positive lung adenocarcinoma patient with acquired resistance to crizotinib: a case report. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:489 10.1186/1756-0500-6-489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]