Abstract

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, apical ballooning syndrome or stress-induced cardiomyopathy is characterised by transient left ventricular dysfunction, mimicking myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease or acute plaque rupture on coronary angiography. The exact mechanism of myocardial dysfunction in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is unknown; however, due to its association with physical and emotional stress, it is postulated that catecholamines play a central role in its pathogenesis. We present a case of a patient who was admitted with acute asthma exacerbation and was treated with β-2 agonist nebulisation and intravenous aminophylline. During her hospital stay she developed Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Background

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was first identified in Japan in 1991.1 It is characterised by typical symptoms of acute coronary syndrome such as chest pain or shortness of breath, associated with ECG changes and raised cardiac biomarkers, however with normal coronary arteries with no evidence of acute plaque rupture on angiography. The exact pathogenesis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is unknown, however several hypotheses exist. These include microvascular spasm causing myocardial stunning or direct myocardial toxicity,2 3 multivessel epicardial coronary artery spasm4 and primary metabolic disturbances causing dysfunctional metabolism of cardiac myocytes affecting either glucose or fatty acid metabolism.5 6 However, the prevailing mechanism is the uncoupling of β-2 adrenoceptors from Gs protein signalling to Gi protein signalling that is seen at very high concentrations of epinephrine and results in negative inotropic effect.7–10 This is known as stimulus trafficking. In some patients, the only stressor observed with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is use of β adrenergic agonists or catecholamine exposure. A possible pathogenic role of catecholamine also comes from studies in which catecholamine levels were carried out in patients with myocardial infarction and in patients with stress-induced cardiomyopathy and their levels were found to be significantly higher in patients with stress-induced cardiomyopathy.11 A recent systemic review of 38 patients has tried to establish a link between respiratory diseases and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy; however, no causal relationship has yet been identified.12 There are a few case reports of patients with acute exacerbation of asthma who developed Takotsubo cardiomyopathy; however, there has only been one case report of a patient receiving intravenous aminophylline infusion and developing Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.13

Case presentation

A 51-year-old woman with multiple myeloma of IgG type and bronchial asthma presented to our facility with a history of worsening shortness of breath for 1 day. The patient had been admitted to the hospital 12 days back with acute asthma exacerbation and had been discharged on oral steroids, montelukast and levofloxacin, a combination of β-2 agonist and a steroid inhaler and proton pump inhibitor. For the patient's multiple myeloma, she had received eight doses of Valcade (bortezomib), the last dose received more than 3 months back. Her disease was currently stable on thalidomide. At the time of presentation to the hospital, the patient had a heart rate of 99 bpm, she was afebrile, and blood pressures were 192/120 mm Hg with a respiratory rate of 38 bpm. Her precordial examination was unremarkable; however, the chest examination revealed bilateral wheeze. Abdominal and central nervous system examinations were unremarkable.

Investigations

The initial laboratory workup revealed respiratory acidosis with hypoxaemia, a pH of 7.10, pCO2 of 72 mm Hg, pO2 of 70 mm Hg and oxygen saturation of 84% on room air. Complete blood count revealed normal haemoglobin with total leucocyte count of 26 600 cells/μL and normal platelets. Her creatinine was slightly increased at 1.3 mg/dL and potassium was 5.5 mmol/L. The initial troponin I was 0.026 ng/mL. The initial ECG (figure 1) recorded in the emergency department was normal. An initial chest X-ray performed in the emergency department was normal. The patient was managed on the lines of acute asthma exacerbation with salbutamol and ipratropium bromide nebulisation, intravenous methylprednisolone, intravenous aminophylline infusion and empiric antibiotics. She was shifted to a special care unit and non-invasive ventilation with bilevel positive airway pressure was initiated. The patient's symptoms and respiratory acidosis improved. After 14 hours of aminophylline infusion the patient started reporting of shortness of breath with jaw pain. An ECG (figure 2) was recorded again which revealed up to 5 mm ST segment elevation with deep T wave inversions in the precordial leads and T wave inversions in the inferior leads. A second test of troponin level turned out to be 5.557 ng/mL. Pro-brain natriuretic peptide (ProBNP) test was performed and was found to be 9490 pg/mL.

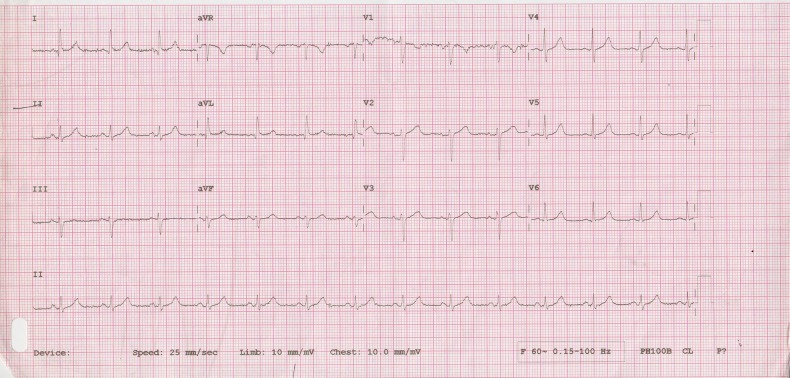

Figure 1.

ECG of the patient on arrival to the hospital, showing sinus rhythm with a normal axis, a heart rate of 75 bpm, no ST-T changes and good R wave progression.

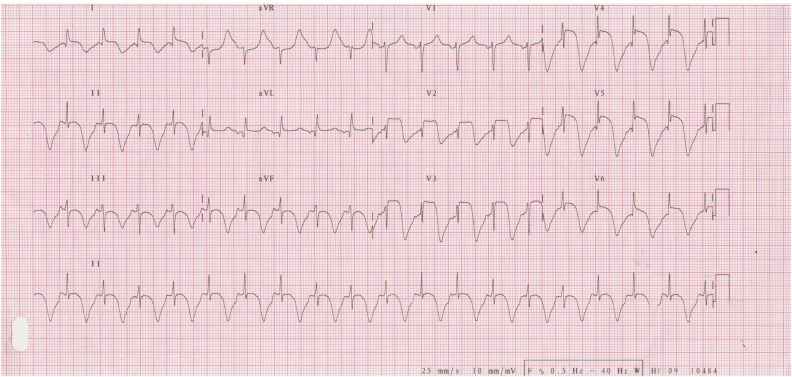

Figure 2.

ECG at time of patient having symptoms of shortness of breath and jaw pain, shows ST segment elevation in leads I, aVL, V2–V6, prolonged QT-interval and deep T wave inversions in all the inferior and anterior precordial leads, the heart rate is 120 bpm.

Differential diagnosis

In a patient with acute onset shortness of breath with jaw pain and ECG changes a diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is strongly suspected. The most common cause of ACS is acute plaque rupture; however, one must keep in mind the possibilities of spontaneous coronary artery dissection, aortic dissection and coronary artery vasospasm. Non-ACS causes would include acute pericarditis, pneumothorax and pulmonary embolism.

Treatment

Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel was started along with intravenous heparin. The patient was electively intubated due to respiratory distress. An informed consent was taken from the family and the patient was shifted to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory. Left heart catheterisation was performed from the right femoral arterial approach. It revealed normal coronary arteries with left dominant system (figures 3–5). A 6-French pigtail catheter was passed into the left ventricle and a left ventriculogram was recorded that revealed an ejection fraction of 30% with apical akinesia and basal segment hyperkinesia (figure 6 and video 1). Aminophylline infusion and salbutamol nebulisation were immediately stopped. She was continued on ipratropium nebulisation and intravenous corticosteroids. The patient was successfully extubated the very next day and then discharged after 48 hours on ACE inhibitor. An echocardiogram was performed subsequently that revealed normal left ventricular systolic function with no segmental wall motion abnormality. β-blocker was not started due to a history of asthma.

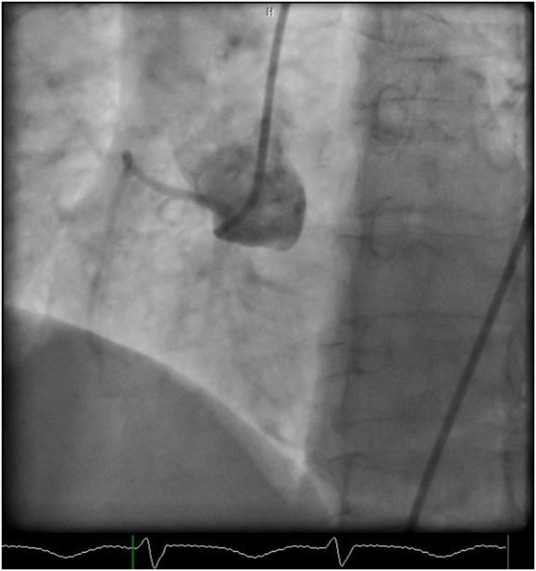

Figure 3.

Cardiac catheterisation still image in LAO view, showing a normally filling non-dominant right coronary artery. LAO, left anterior oblique.

Figure 4.

Cardiac catheterisation still image in RAO caudal view, showing a normally filling dominant left circumflex artery. RAO, right anterior oblique.

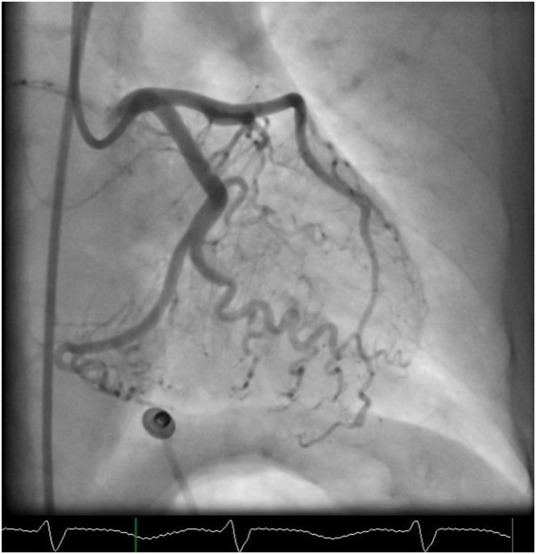

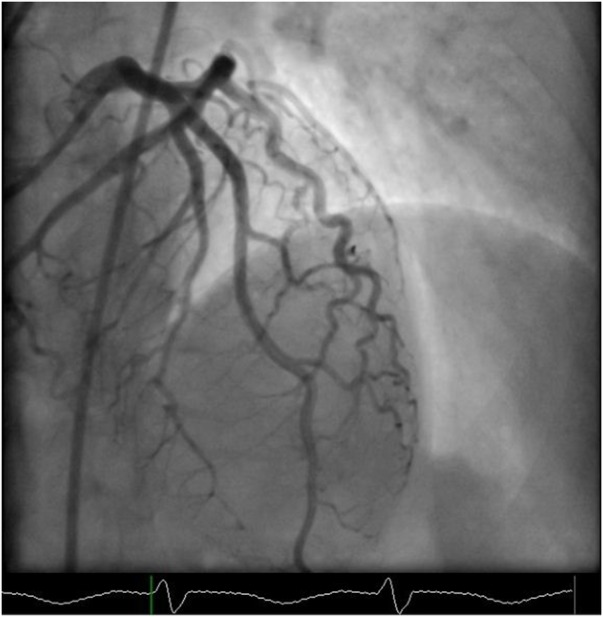

Figure 5.

Cardiac catheterisation still image in AP cranial view, showing a normally filling LAD. Notice that the LAD has one large first septal branch that gives off further smaller septal branches. AP, anteroposterior; LAD, left anterior descending artery.

Figure 6.

Cardiac catheterisation still image of left ventriculogram in RAO view showing apical ballooning. RAO, right anterior oblique.

Video 1.

Left ventriculogram in RAO view showing apical ballooning. RAO, right anterior oblique.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged and followed up with the cardiologist. She is currently asymptomatic.

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or apical ballooning syndrome (ABS) is a syndrome distinct from ACS. It is characterised by reversible myocardial dysfunction associated with ST-T changes seen on the ECG, elevation of cardiac enzymes and presence of an acute stressor. Ever since the first case was reported by Dote et al1 from Japan several case reports and case series of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy have been reported from around the world. The largest cohort of 6837 affected patients was reported by Deshmukh et al14 from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) in the USA.

Two diagnostic criteria have been proposed for the diagnosis of Takotsubo syndrome, namely, the Modified Mayo Clinic Criteria for diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy15 and the recently proposed diagnostic criteria published in the European Journal of Heart Failure titled ‘Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology’.16

Contrary to popular belief, Takotsubo is not an uncommon condition. Numerous case reports and case series have been published describing several variants of the condition.17–22 A number of case reports have now been published of patients developing Takotsubo cardiomyopathy as a result of drug administration during diagnostic tests such as dobutamine stress echo,23–26 anaesthesia administration,27 epinephrine administration28–30 and with iatrogenic thyrotoxicosis.31 Case reports have also described patients who developed ABS following administration of β-2 agonists for acute asthma exacerbation.32–38 However, after searching PubMed and Google Scholar we only found one case report in the English language of a patient developing ABS following aminophylline infusion.13

Aminophylline is pharmacologically classified as a methylxanthine. Its exact mechanism of action is unknown; however, it has been proposed that it acts as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. This in turn results in an increase in intracellular concentration of cyclic AMP (cAMP). An increase in intracellular activity of cAMP results in cardiac stimulation and smooth muscle relaxation.39 Evidence of this important effect also available from animal studies which suggest that methylxanthines potentiate cardiac inotropic response to catecholamines by stimulating the release of norepinephrine from cardiac β adrenergic nerve endings and also stimulate the release of catecholamines from adrenal medulla.40 41

The precise aetiology and pathophysiology of Takotsubo syndrome remains unknown and several mechanisms have been proposed. The current prevailing hypothesis on the pathophysiology of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is the coupling of β-2 adrenoceptor to Gi proteins rather than Gs proteins in response to high concentrations of epinephrine.7–9 At physiological concentrations of epinephrine and norepinephrine, activation of β-1 and β-2 adrenoceptors triggers a positive inotropic response from cardiac myocytes due to intracellular activation of Gs proteins resulting in increased production of cAMP.42 Epinephrine has higher affinity for β-2 adrenoceptors and at supraphysiological concentrations epinephrine triggers a negative inotropic response from cardiac myocytes. This change in response occurs due to a switch in coupling of β-2 adrenoceptors from Gs protein signalling to Gi protein signalling.43 44 Once the higher concentrations of epinephrine are cleared from the circulation, the β-2 adrenoceptors switch back to Gs protein coupling, explaining the recovery of ventricular function in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy has been classified into primary and secondary subtypes.16 Primary Takotsubo syndrome is one where there is no identifiable stressor and the patient seeks help due to symptoms associated with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Secondary Takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurs in patients who are already hospitalised for a medical, surgical or psychiatric illness and develop ABS as a result of the treatment received for the illness, as seen in our patient. Our patient's possible mechanism of development of ABS was a result of aminophylline-induced potentiation of circulating β agonists resulting in uncoupling of β-2 adrenoceptors, causing myocardial apical stunning and depression of myocardial function. This effect was possibly enhanced by the inhaled β-2 agonists administered for the treatment of the patient's acute asthma exacerbation and, presumably due to the high levels of circulating catecholamines caused by the acute illness.

Learning points.

Takotsubo syndrome can develop in patients who have been admitted for acute exacerbation of chronic illnesses.

It has been associated with patients receiving β-2 agonist drugs and aminophylline.

Patients receiving β-2 agonists and aminophylline should be monitored for symptoms and signs of stress-induced cardiomyopathy.

Apical ballooning syndrome should be suspected in patients who develop chest pain or worsening shortness of breath with ECG changes.

Footnotes

Contributors: The patient was admitted under care of JMT (Assistant Professor and Consultant Interventional cardiologist). The coronary angiogram was performed by JMT. YHK assisted JMT in performing the coronary angiogram. He was actively involved in the management of the patient while she was admitted under JMT service in the coronary care unit and while in the special care unit. The coronary angiogram and echocardiogram was reported by JMT. The case report was written by YHK under supervision of JMT. The literature search, designing and formulation of the case report was done by YHH. JMT did the final editing of the case report for submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Dote K, Sato H, Tateishi H et al. [Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: a review of 5 cases]. J Cardiol 1991;21:203–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nef HM, Möllmann H, Kostin S et al. Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy: intraindividual structural analysis in the acute phase and after functional recovery. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2456–64. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM et al. Apical ballooning syndrome or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1523–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbaro G et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation 2008;118:2754–62. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Testa M, Feola M. Usefulness of myocardial positron emission tomography/nuclear imaging in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. World J Radiol 2014;6:502–6. 10.4329/wjr.v6.i7.502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obunai K, Misra D, Van Tosh A et al. Metabolic evidence of myocardial stunning in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a positron emission tomography study. J Nucl Cardiol 2005;12:742–4. 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2005.06.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akashi YJ, Nef HM, Lyon AR. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of Takotsubo syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:387–97. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S et al. Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy—a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:22–9. 10.1038/ncpcardio1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paur H, Wright PT, Sikkel MB et al. High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a β2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: a new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2012;126:697–706. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.111591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams R, Arri S, Prasad A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of Takotsubo syndrome. Heart Fail Clin 2016;12:473–84. 10.1016/j.hfc.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 2005;352:539–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa043046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manfredini R, Fabbian F, Giorgi AD et al. Heart and lung, a dangerous liaison-Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy and respiratory diseases: a systematic review. World J Cardiol 2014;6:338–44. 10.4330/wjc.v6.i5.338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khurshid SM, Abubaker J, Noor A et al. Aminophylline infusion leading to broken heart syndrome in a Pakistani women. Chest 2008;134:c37002-c 10.1378/chest.134.4_MeetingAbstracts.c37002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshmukh A, Kumar G, Pant S et al. Prevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. Am Heart J 2012;164:66–71.e1. 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008;155:408–17. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a position statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:8–27. 10.1002/ejhf.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chahal GS, Polena S, Fard BS et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: case report and review of the literature. Proc West Pharmacol Soc 2008;51:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laghari AH, Khan AH, Kazmi KA. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: ten year experience at a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:932 10.1186/1756-0500-7-932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagan J, Connor V, Saravanan P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy case series: typical, atypical and recurrence. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015:bcr2014208741 10.1136/bcr-2014-208741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merchant EE, Johnson SW, Nguyen P et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case series and review of the literature. West J Emerg Med 2008;9:104–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takizawa M, Kobayakawa N, Uozumi H et al. A case of transient left ventricular ballooning with pheochromocytoma, supporting pathogenetic role of catecholamines in stress-induced cardiomyopathy or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2007;114:e15–17. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurst RT, Prasad A, Askew JW et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a unique cardiomyopathy with variable ventricular morphology. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:641–9. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arias AM, Oberti PF, Pizarro R et al. Dobutamine-precipitated Takotsubo cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction: a multimodality image approach. Circulation 2011;124:e312–15. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margey R, Diamond P, McCann H et al. Dobutamine stress echo-induced apical ballooning (Takotsubo) syndrome. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009;10:395–9. 10.1093/ejechocard/jen292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosley WJ, Manuchehry A, McEvoy C et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by dobutamine infusion: a new phenomenon or an old disease with a new name. Echocardiography 2010;27:E30–3. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.01089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasconcelos Filho FJ, Gomes CA, Queiroz OA et al. Dobutamine stress echocardiography-induced broken heart syndrome (Takotsubo syndrome). Arq Bras Cardiol 2009;93:e5–7. 10.1590/S0066-782X2009000700014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Littlejohn FC, Syed O, Ornstein E et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with anesthesia: three case reports. Cases J 2008;1:227 10.1186/1757-1626-1-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laínez B, Ureña M, Alvarez V et al. Iatrogenic Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to catecholamine administration. Rev Esp Cardiol 2009;62:1498–9. 10.1016/S0300-8932(09)73140-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litvinov IV, Kotowycz MA, Wassmann S. Iatrogenic epinephrine-induced reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: direct evidence supporting the role of catecholamines in the pathophysiology of the “broken heart syndrome”. Clin Res Cardiol 2009;98:457–62. 10.1007/s00392-009-0028-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundbøll J, Pareek M, Høgsbro M et al. Iatrogenic Takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by locally applied epinephrine and cocaine. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2013202401 10.1136/bcr-2013-202401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon SA, Yang JH, Kim MK et al. A case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with iatrogenic thyrotoxicosis. Int J Cardiol 2010;145:e111–13. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmoush FY, Barbour MF, Noonan TE et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new perspective in Asthma. Case Rep Cardiol 2015;2015:640795 10.1155/2015/640795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendoza I, Novaro GM. Repeat recurrence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy related to inhaled beta-2-adrenoceptor agonists. World J Cardiol 2012;4:211–13. 10.4330/wjc.v4.i6.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel B, Assad D, Wiemann C et al. Repeated use of albuterol inhaler as a potential cause of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Case Rep 2014;15:221–5. 10.12659/AJCR.890388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rennyson SL, Parker JM, Symanski JD et al. Recurrent, severe, and rapidly reversible apical ballooning syndrome in status asthmaticus. Heart Lung 2010;39:537–9. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salahuddin FF, Sloane P, Buescher P et al. A case of apical ballooning syndrome in a Male with status asthmaticus; highlighting the role of B2 agonists in the pathophysiology of a reversible cardiomyopathy. J Commun Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2013;3(2):1–5. 10.3402/jchimp.v3i2.20530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanojevic DA, Alla VM, Lynch JD et al. Case of reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in status asthmaticus. South Med J 2010;103:964 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181eb349d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venditti F, Bellandi B, Parodi G. Fatal Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy recurrence after β2-agonist administration. Int J Cardiol 2012;161:e10–11. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galanter JM, Boushey HA, Katzung BG et al. Drugs used in asthma. Basic & clinical pharmacology, 13e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.RALL TW, WEST TC. The potentiation of cardiac inotropic responses to norepinephrine by theophylline. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1963;139:269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudusky BM. Aminophylline: exploring cardiovascular benefits versus medical malcontent. Angiology 2005;56:295–304. 10.1177/000331970505600309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Port JD, Bristow MR. Altered beta-adrenergic receptor gene regulation and signaling in chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2001;33:887–905. 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heubach JF, Blaschke M, Harding SE et al. Cardiostimulant and cardiodepressant effects through overexpressed human beta2-adrenoceptors in murine heart: regional differences and functional role of beta1-adrenoceptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2003;367:380–90. 10.1007/s00210-002-0681-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zamah AM, Delahunty M, Luttrell LM et al. Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor regulates its coupling to Gs and Gi. Demonstration in a reconstituted system. J Biol Chem 2002;277:31249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]