Abstract

Aspergillus species produces a wide spectrum of fungal diseases like endophthalmitis and fungal keratitis ophthalmologically, but there has been no report about blepharitis caused by Aspergilus flavus to date. Herein, we report a 61-year-old ethnic Han Taiwanese male who had suffered from pain with burning and foreign body sensation after an insect bite on his left eye. Specimens from bilateral eyelids suggested infection of A. flavus, whereas corneal scraping showed the presence of Gram-negative bacteria. He was admitted for treatment of infectious keratitis with topical antibiotic and antifungal eye drops. Two weeks after discharge, recurrent blepharitis and keratitis of A. flavus was diagnosed microbiologically. Another treatment course of antifungal agent was resumed in the following 6 months, without further significant symptoms in the following 2 years. Collectively, it is possible for A. flavus to induce concurrent keratitis and blepharitis, and combined treatment of keratitis as well as blepharitis is advocated for as long as 6 months to ensure no recurrence.

Introduction

Aspergillus species are ubiquitous, and aspergillosis produces a wide spectrum of fungal diseases with variable susceptibility. Although the spores are occasionally inhaled, the fungal species seldom arouse vigorous systemic immune response. Although aspergillosis can be devastating in high-risk individuals, including the immunocompromised, it can still cause asthma, sinusitis, endophthalmitis, and fungal keratitis for those immunocompetent individuals without risk factors.1,2 Among Aspergillus species, Aspergillus flavus is only less common than Aspergillus fumigatus as a cause of invasive aspergillosis in the human body and among the most common Aspergillus species causing fungal keratitis.3,4 However, compared with the various pathogens of infectious blepharitis such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites, fungi are rarely encountered.5 To date, there has been no report on blepharitis caused by A. flavus. Herein, we report a case of recurrent fungal blepharitis with concurrent fungal keratitis, both of which were salvaged by continuous treatment with topical antifungal agents.

Case Report

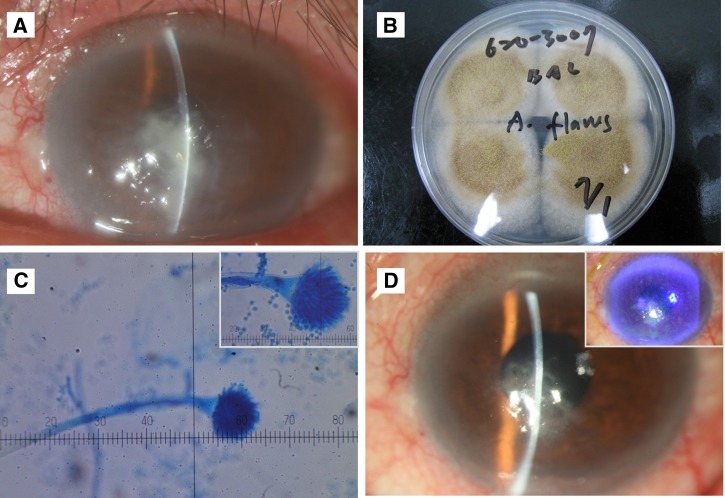

A 61-year-old ethnic Han Taiwanese male with previous surgical history of meningioma and cataract had suffered from pain with burning and foreign body sensation after an insect bite on his left eye for 1 week, with associated symptoms of purulent discharge, tearing, hyperemia, and blurred vision. He visited a local clinic where an unknown tiny bug was removed and unknown eye drops were given which were not effective. The patient then visited our clinic of a tertiary hospital, and was admitted due to suspected infectious keratitis. On examination, his best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was only counting fingers at the distance of 10 cm for the left eye and was 20/40 for the right eye. Bilateral crusty and thickened eyelid margins, hyperemic at the lash base, and conjunctival injection were noted. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy showed a crescent-shaped, greyish-white corneal stromal infiltration (4.4 × 3.2 mm) with fluffy margins (Figure 1A ) located centrally. In addition, partial corneal melting without satellite lesions was also found, whereas the anterior chamber was free of hypopyon. Then, corneal scraping and crust from the eyelid were sent for microbiological investigation.

Figure 1.

Concurrent fungal keratitis and blepharitis at the first admission. (A) A crescent-shaped, greyish-white corneal stromal infiltration (4.4 × 3.2 mm) with fluffy margins, (B) green-yellow colonies with white edge, (C) conidiophores with classical radiate conidia (methylene blue stain, ×400), (D) central scar with residual punctate epithelial erosions, much improved in comparison with previous status.

During admission, the patient was treated with hourly empirical topical fortified antibiotics including cefazolin 25 mg/mL (Union Chemical and Pharmaceutical, Taipei, Taiwan), amikacin 25 mg/mL (Taiwan Biotech, Taoyuan, Taiwan), and antifungal natamycin ophthalmic suspension 5% (Alcon Laboratory, Fort Worth, TX). Specimens from bilateral eyelids showed growth of green-yellow colonies with white edge, suggestive of A. flavus (Figure 1B). Light microscopy with methylene blue stain demonstrated conidiophores (Figure 1C) with classical radiate conidia (Figure 1C, inset), whereas corneal scraping from the left eye revealed Gram-negative bacteria only, without evidence of fungal colonization. By the time of discharge, BCVA of left eye improved to 20/200, and slit-lamp revealed significantly decreased corneal opacity and haze with only residual stromal infiltrates (Figure 1D); there was only a central scar with residual punctate epithelial erosions stained with fluorescein (Figure 1D, inset).

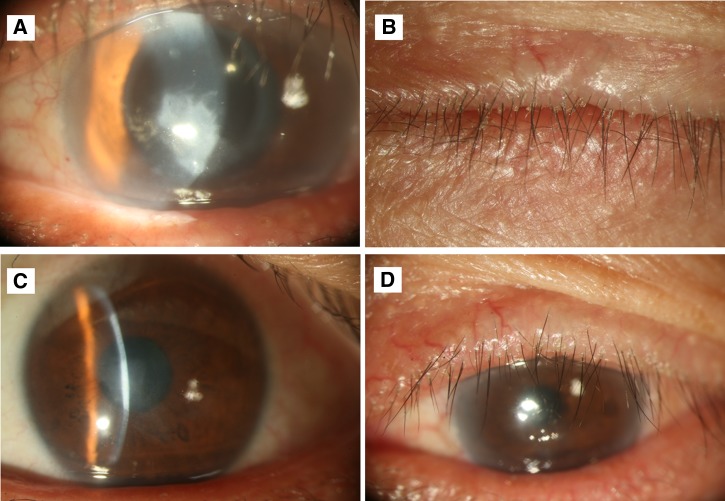

However, 14 days after being discharged, the patient returned to our hospital due to progressively blurred vision and lid margin itchiness without ocular pain. On examination, there was greyish-white stromal feathery infiltrate extending from the residual central corneal epithelial defect (Figure 2A ). Eyelid margin telangiectasia and plugging of meibomian gland orifices indicated flare-up of blepharitis (Figure 2B). For relapsing blepharitis and keratitis without systemic involvement, bilateral eyelid crust and corneal scraping of left eye were sent for microbiological assessments, and the growth from bilateral eyelid specimens turned out as A. flavus again. Different to previous management, topical tetracycline ointment 1% (Synpac-Kingdom Pharmaceutical, Taipei, Taiwan) and natamycin ophthalmic suspension 5% (Alcon Laboratory, Fort Worth, TX) were given four times daily and hourly, respectively, for 2 weeks, which were both tapered to twice daily for the succeeding 6 months and the patient had recovered without further symptoms. In the following 2 years, with proper eyelid hygiene, chronic blepharitis was much less active without recurrence of keratitis (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Concurrent fungal keratitis and blepharitis at the second admission. (A) Greyish-white stromal feathery infiltrate extending from the residual central corneal epithelial defect, (B) marginal telangiectasia and plugging of meibomian gland orifices of eyelid, (C) clear corneal appearance, (D) no abnormalities of eyelid.

Discussion

Blepharitis is a chronic eyelid disorder that seldom causes visual impairment, rendering its easily overlooked influence to ocular morbidity. Definite treatment of blepharitis is lacking and recurrence is common. Severe blepharitis usually presents with complications such as conjunctivitis, dry eye syndrome, keratitis, or even corneal ulceration. Although antifungal agent is not recommended as empirical treatment of keratitis, the importance of timely microbiological testing cannot be overemphasized, especially in the case of recurrent keratitis.6

Fungal infection is commonly associated with agriculture or outdoor activities.7 Our patient, a farmer with a contact history of insects or unknown vegetative matter, was surely a candidate for Aspergillus-related infection. Given that fungal infection is usual in immunocompromised individuals, we assumed that there were undetected underlying ocular disorders.8 The eyelid disorder, such as blepharitis, might have predisposed our patient to keratitis, and prolonged the course of treatment.9

The relationship between A. flavus infection and blepharitis remains controversial. In a semiquantitative study, colonies of A. flavus were isolated from one of 90 eyes with blepharitis, but not from 66 normal eyes.10 It was indeterminate whether Aspergillus spp. would be present because of inflammation on eyelid margins or as being transient flora.10 In addition, in a case report of vernal keratoconjunctivitis superimposed with A. flavus keratitis, it was postulated that transient mold-containing microbiota of external ocular surfaces can really invade and initiate infection in compromised cornea.11 Accordingly, the preexisting fungal blepharitis in our patient might have caused recurrence of fungal keratitis soon after he was discharged. To prevent recurrence of fungal keratitis, the treatment strategy should include eradication of eyelid mycosis, for which ocular surface protection with tear substitutes as well as extended use of topical antifungal therapy are suggested in chronic blepharitis with suspected fungal keratitis.

To treat Aspergillus-related fungal keratitis, there is no gold standard yet. Generally, it is divided into three groups: azoles, polyenes, and allylamines. Topical antifungal agents still remain the major therapeutic choice and first-line treatment, and although there is no single drug or combinations that have proved to be more effective in treating fungal keratitis, amphotericin B, voriconazole, and natamycin are being routinely used to treat fungal keratitis.12 Natamycin is the only commercially available topical antifungal agent, which is used as the standard regimen in our hospital to treat Aspergillus-related fungal keratitis, and the patient's diseased eye obtained good outcome without recurrence during follow-up after topical natamycin application. We did not consider manufactured amphotericin B eye drops as solitary treatment or double fungal treatments because Fusarium infection cannot be excluded initially, on which amphotericin B has minimal effect.12 Also, the visual acuity of our patient has gradually improved under natamycin administration, so multiple medications or alternation of therapeutic agent seems unnecessary. Given the recurrent tendency of fungal infection, we recommend an extended course of natamycin administration and tapering it according to clinical response. Except for natamycin, use of voriconazole has been described in ophthalmic literatures.13 As for topical amphotericin B, which is also active against Aspergillus spp., it has poorer penetration through cornea with intact epithelium compared with topical natamycin.14

In conclusion, it is possible for A. flavus to induce concurrent keratitis and blepharitis according to the presentation of our case. The administrations of tetracycline for blepharitis and natamycin for A. flavus infection may be considered as an effective treatment, but the therapeutic period should not be shorter than 6 months. Larger case series or clinical trials are merited to recommend more precise dosage and duration of topical antibiotics and to prevent side effects if any.

Disclaimer: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this Journal.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG3D0901, CMRPG3E0931, and CMRPG3F1471) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104-2314-B-182A-007) in Taiwan to Hung-Chi Chen.

Authors' addresses: Chia-Yi Lee, Department of Ophthalmology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan, and Department of Ophthalmology, Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan, E-mail: ao6u.3msn@hotmail.com. Yi-Ju Ho, Hsin-Chiung Lin, Ching-Hsi Hsiao, David Hui-Kang Ma, Chi-Chun Lai, and Hung-Chi Chen, Department of Ophthalmology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan, E-mails: freedomshield3800@gmail.com, hsinchiung@gmail.com, hsiao.chinghsi@gmail.com, davidhkma@yahoo.com, chichun.lai@gmail.com, and mr3756@cgmh.org.tw. Chi-Chin Sun, Department of Ophthalmology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung, Taiwan, E-mail: arvin.sun@msa.hinet.net.

References

- 1.Segal BH. Aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1870–1884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badiee P, Alborzi A, Nejabat M. Detection of Aspergillus keratitis in ocular infections by culture and molecular method. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:291–296. doi: 10.1007/s10792-011-9457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan S, Manavathu EK, Chandrasekar PH. Aspergillus flavus: an emerging non-fumigatus Aspergillus species of significance. Mycoses. 2009;52:206–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khairallah SH, Byrne KA, Tabbara KF. Fungal keratitis in Saudi Arabia. Doc Ophthalmol. 1992;79:269–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00158257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson WB. Blepharitis: current strategies for diagnosis and management. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:170–179. doi: 10.1139/i08-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalmon C, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Prajna NV, Prajna L, Das MR, Kumar JA, Mascarenhas J, Margolis TP, Whitcher JP, Jeng BH, Keenan JD, Chan MF, McLeod SD, Acharya NR. The clinical differentiation of bacterial and fungal keratitis: a photographic survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1787–1791. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Athmanathan S, Rao GN. The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: a 10-year review at a referral eye care center in south India. Cornea. 2002;21:555–559. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vilela RC, Vilela L, Vilela P, Vilela R, Motta R, Pôssa AP, de Almeida C, Mendoza L. Etiological agents of fungal endophthalmitis: diagnosis and management. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:707–721. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9854-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCulley JP, Shine WE. Changing concepts in the diagnosis and management of blepharitis. Cornea. 2000;19:650–658. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seal DV, McGill JI, Jacobs P, Liakos GM, Goulding NJ. Microbial and immunological investigations of chronic non-ulcerative blepharitis and meibomianitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:604–611. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.8.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sridhar MS, Gopinathan U, Rao GN. Fungal keratitis associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2003;22:80–81. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200301000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Badriyeh D, Neoh CF, Stewart K, Kong DC. Clinical utility of voriconazole eye drops in ophthalmic fungal keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:391–405. doi: 10.2147/opth.s6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta H, Mehta HB, Garg P, Kodial H. Voriconazole for the treatment of refractory Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:243–245. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.40369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Day DM, Head WS, Robinson RD, Clanton JA. Corneal penetration of topical amphotericin B and natamycin. Curr Eye Res. 1986;5:877–882. doi: 10.3109/02713688609029240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]