Abstract

Finding ways to deliver high-quality health care to an increasingly diverse population is a major challenge for the American health care system. The persistence of racial and ethnic disparities in health care access, quality, and outcomes has prompted considerable interest in increasing the cultural competence of health care, both as an end in its own right and as a potential means to reduce disparities. This article reviews the potential role of cultural competence in reducing racial and ethnic health disparities, the strength of health care organizations’ current incentives to adopt cultural competence techniques, and the limitations inherent in these incentives that will need to be overcome if cultural competence techniques are to become widely adopted.

Keywords: cultural competence, cultural diversity, delivery of health care, disparities, ethnic groups, health care systems, health policy, incentives, race

Background

Persistence of Disparities

Literature on health care access and outcomes shows a persistent gap between majority and minority populations.1–6 These disparities have many causes, including low socioeconomic status (SES). Minority Americans are disproportionately represented among the poor, the unemployed, and the undereducated, and lower SES is correlated with poorer access to health care services and poorer health outcomes.7 But even minority Americans who are not socioeconomically disadvantaged have systematically different health experiences from nonminority Americans.6, 8–13 Studies of the Veterans Health Administration, Medicare, and single health plans make it clear that minority Americans have different experiences in the health care system, even when they have similar medical conditions and health coverage.14–23 Because financial barriers should not be a factor in these cases, researchers have concluded that the health care delivery system must be doing an inferior job in meeting the needs of racial and ethnic minorities compared to its performance in meeting the needs of the nonminority population.

Promise of Cultural Competence

Increasing linguistic and cultural competence provides one potential way to address flaws in the delivery system. Communication with physicians presents a problem for one in five Americans receiving health care, and the percentage rises to 27 percent among Asian Americans and 33 percent among Hispanics.6 These barriers have a negative impact on utilization, satisfaction, and possibly adherence. People with language barriers or limited English proficiency (LEP) have fewer physician visits and receive fewer preventive services, even after controlling for such factors as literacy, health status, health insurance, regular source of care, and economic indicators.24–28 They have lower satisfaction, even when compared with patients of the same ethnicity who have good English skills.29–31 Reducing disparities will require surmounting not only these linguistic barriers but broader cultural ones as well.

Research over the past two decades32–35 has shown that quality health care requires attention to differences in culture—the “integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values and institutions of a racial, ethnic, religious or social group.”36p.iv Although quality challenges arise even in homogeneous environments, growing diversity among patients increases the likelihood that differences between patients and providers will lead to diagnostic errors; missed opportunities for screening; failure to take into account differing responses to medication; harmful drug interactions resulting from simultaneous use of conventional and traditional folk medications; and inadequate patient adherence to clinician recommendations on prescriptions, self-care, and follow-up visits. The idea of cultural competence therefore extends beyond language to include the full “set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency or amongst professionals and enables that system, agency or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations”36p.iv (see other definitions as well37–42). For the remainder of this article, the term cultural competence will be used to encompass linguistic competence as well.

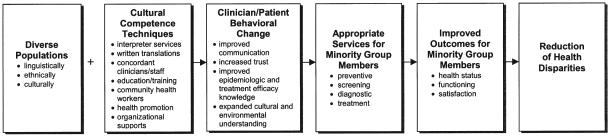

One recent analysis provided a model for how health care organizations could use cultural competence techniques to reduce racial and ethnic disparities43 (Figure 1). Cultural competence techniques include such interventions as the use of interpreter services, racially or linguistically concordant clinicians and staff, culturally competent education and training, and culturally competent health education. Cultural competence techniques, introduced singly or in combination, could change clinician and patient behavior by improving communication, increasing trust, improving racially or ethnically specific knowledge of epidemiology and treatment efficacy, and expanding understanding of patients’ cultural behaviors and environment. These behavioral changes lead to appropriate services for minority group members, such as tailored preventive care, timely health screenings, indicated diagnostic tests, and early intervention and treatment. Appropriate services in turn result in improved outcomes, such as better health status, functioning, and satisfaction. The final result is a decrease in disparities in health care access and quality and health outcomes.43

Figure 1.

Reducing Health Disparities Through Cultural Competence. Source: Brach and Fraser, Medical Care Research and Review (57 Supplement 1)

pp. 181–217, copyright © 2000 by Sage Publications. Adapted by permission of Sage Publications.

Support for Cultural Competence

In recent years, national organizations have supported this idea of cultural competence, both as an end in itself and a means for reducing disparities. A growing body of federal and state laws, as well as quasi-governmental actions, seeks to guarantee cultural competence as an entitlement. These laws and actions spring from the premise that we as a society value some characteristics of health care—such as ensuring informed consent, choice of providers, and equitable treatment—regardless of their impact on outcomes.44,45 For example, the 1997 Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities, adopted by the President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry, recommended a wide range of measures to promote and assure health care quality and value and protect consumers and workers in the health care system.46 The Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities requires linguistic and cultural competence in several major areas, including information disclosure, access to emergency services, participation in treatment decisions, and respect and nondiscrimination. Although health care organizations are not required to follow the recommendations of the Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities, federal agencies are actively supporting its implementation.

More recently, the Office of Minority Health of the Department of Health and Human Services spotlighted cultural competence by publishing national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) in health care.47 The 14 CLAS standards span the delivery of culturally competent care, language access services, and organizational supports for cultural competence. The promulgation of these standards, taken with other activities by the federal government (including actions that have been undertaken in the role of health services purchaser, as described later), combine to create a federal climate promoting cultural competence.

In the current very competitive health care system, health care organizations must respond to the financial incentives of the marketplace.

Meanwhile, several health care organizations have pioneered programs designed to increase cultural competence. Early findings from the authors’ qualitative research in this area suggest that these efforts are largely mission-driven. Despite the increasingly competitive environment in which they operate, many health care organizations adhere to a public health ethic whereby improving outcomes and reducing racial and ethnic disparities are motivations in their own right. The older nonprofit health maintenance organizations, for example, were established under the premise that managing care would lead to improved health care. It is not a coincidence that many of the health plans providing leadership in the area of cultural competence (e.g., Kaiser Permanente and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care) represent a generation that behaved in many ways like public health agencies, with a fixed budget, a fixed population, and a mission to improve access to and continuity of care while controlling costs.48 Some newer health care organizations founded to serve largely publicly insured populations share these values. All of these health care organizations have implemented cultural competence techniques based on the belief—often without evidence—that these techniques have the power to improve outcomes and reduce disparities.

But in the current very competitive health care system, health care organizations must respond to the financial incentives of the marketplace. Health care organizations are likely to adopt cultural competence techniques when it makes business sense for them to do so. The following analysis, drawn from a review of the academic literature and trade press, identifies the major financial incentives that constitute the business case for health care organizations to increase their cultural competence.

The Business Case for Culturally Competent Health Care

Health care organizations have four interrelated financial incentives to provide culturally competent care. Together, these constitute a business case for cultural competence.

Appeal to Minority Consumers

The first incentive for health care organizations to become culturally competent is to increase their appeal to minority consumers, thereby enlarging their market share. Racial and ethnic minority Americans constitute a large and growing part of the health care market. Minority groups accounted for 70 percent of the total population growth in the decade between 1988 and 1998.49 Four of ten Americans will belong to a racial or ethnic minority group by 2030.50 In some markets, such as California and New Mexico, minority Americans already constitute a majority of the population.51

By advertising their cultural competence, health care organizations could attract the business of minority group members. Americans directly choose their health plans and providers by making a selection from among the options given to them by employers or public insurance programs. Even when health plan options are limited, employees can choose from among competing health systems or provider groups within plans. Because Americans are given the option to change their selections on a regular basis, health care organizations must deliver on their promises to retain patients.

Some health care organizations, therefore, are looking for ways to appeal to racial and ethnic minority Americans.49 Articles in the provider trade press52–54 focus on how health care organizations can use cultural competence to draw in consumers who want easier and more comfortable access and service. As Mitchell notes, “the culturally diverse consumer no longer represents a niche market but a market that offers the opportunity for increased revenue potential.”55 In an article in Profiles in Healthcare Marketing, Herreria describes an array of strategies managed care organizations have adopted to expand in Hispanic, Asian, African American, and other ethnic markets.56 In other words, at least some health care organizations may see that an increased emphasis on cultural competence will help them attract and retain new enrollees in a racially and ethnically diverse market.49

Compete for Private Purchaser Business

A second financial incentive for cultural competence can be to increase the health care organization’s performance on quality measures of interest to private purchasers, particularly in competitive markets with a large minority population. The Health Plan Employers Data and Information Set (HEDIS), developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), is an example of such measures for health plans. HEDIS is intended to give purchasers and consumers a basis for comparison among health plans. It can be used in two ways to judge the cultural competence of a health plan. First, the most recent (3.0) version of HEDIS includes a few indicators of the availability of linguistically appropriate clinical and administrative services.57,58 Second, overall HEDIS scores can be used to assess the quality of plans that serve a high proportion of minority enrollees. The HEDIS data are not reported by racial and ethnic groups, and therefore the quality of care for minority enrollees cannot be separately analyzed.59 However, poor service to minority groups in plans that have a sizable proportion of minority enrollees would reduce those plans’ overall performance on HEDIS measures. NCQA also requires health plans to conduct the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS) as part of HEDIS. The CAHPS core survey includes such items as satisfaction with choice of physicians and whether physicians explain things in an understandable way and show respect for what the patient has to say. The CAHPS supplemental survey asks about difficulties in communication and the availability of interpreters. CAHPS, therefore, provides additional measures of cultural competence.

These measures are increasingly used by private purchasers to guide their decisions. For example, a group of large private purchasers and coalitions—the so-called “V-8” group—has developed a common request for information (RFI) to use in soliciting bids from health plans. This common RFI calls for not only HEDIS and CAHPS data, but also for additional information related to safety, quality, and cultural competence. For example, in the area of diabetes management, the RFI asks plan applicants if they have special arrangements to help diabetic members whose primary language is not English or who have particular cultural preferences. It also asks whether the plan gives provider educational material identifying disease incidence by race or ethnicity, and whether it gives providers information on treatment outcomes and pharmacology by race or ethnicity.60 To the extent that purchasers and consumers factor in HEDIS, CAHPS, and RFI data when selecting health care organizations that serve minority populations, culturally competent health care organizations will fare better than others.

Respond to Public Purchaser Demands

A third business incentive for culturally competent health care is that Medicare, Medicaid, and other public purchasers are placing increased emphasis on cultural competence and quality. Any health care organization wanting Medicare or Medicaid business must comply with their respective regulations and purchasing practices. A significant proportion of health plans have Medicare or Medicaid business,61 so this is a powerful tool for promoting cultural competence.

The major legal underpinning for Medicare and Medicaid rules lies in Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. It states: “No person in the United States shall, on grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving financial assistance.”62 Although Title VI only explicitly addresses discrimination, a policy guidance document issued by the Department of Justice, the lead enforcement agency, expressly recognizes the obligation Title VI imposes to provide meaningful access to people with limited English proficiency.63 Department of Justice regulations have construed the law broadly to include all operations of an organization, not just that portion that receives federal funds, and to apply to subcontractors as well.64,65 Remedies for violations of Title VI include injunctive relief, corrective action plans, termination of federal funds, and damages.65 A 2000 Presidential Executive Order66 requires that federal agencies develop guidance for recipients of federal funds to ensure that they are meeting Title VI obligations to LEP individuals, and also requires them to meet those same standards for providing meaningful access. A recent report from the Office of Management and Budget noted that language assistance services confer significant benefits on the LEP population and states that the administration has commenced to implement the Executive Order’s provisions.67 The Office of Civil Rights of the Department of Health and Human Services has issued a policy guidance identifying ways to secure Title VI compliance; this office investigates complaints and undertakes compliance reviews.63

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS, formerly the Health Care Financing Administration), the federal agency that administers the Medicare and Medicaid programs, is encouraging cultural competence in several ways. First, Medicare + Choice regulations require cultural competence in provision of care by health professionals, coordinated care plans, and networks.68

Second, federal Medicaid rules explicitly reference Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and have other provisions obliging state Medicaid agencies and providers to ensure that services are provided in a linguistically and culturally appropriate manner.65,68 In particular, Medicaid managed care rules under the Balanced Budget Amendment include several provisions related to linguistic and cultural competence.69 These requirements are increasingly important because of growth in the number of beneficiaries covered under capitation. In 1998, almost 36 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries—14.7 million people—were receiving care from health maintenance or health insuring organizations.70 Of particular note is the requirement that managed care organizations (MCOs) ensure “that services are provided in a culturally competent manner to all enrollees, including those with limited English proficiency and diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds” (438.206(e)(2)). In addition, the rules specify that state agencies are to require that each MCO make written information available in prevalent languages, make oral interpretation services available, and notify enrollees and potential enrollees of their availability (438.10(b)(3), (4), and (5)).

Third, CMS has developed a quality improvement system for managed care (QISMC), a set of standards and guidelines to ensure quality for and protection of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries served by managed care organizations.71 QISMC standards and guidelines identify MCO responsibilities toward people with limited English proficiency and of diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. The standards specify that MCOs need to guarantee access to clinical and nonclinical services; have a provider network capable of meeting the cultural, linguistic, and informational needs of diverse beneficiaries; educate employees on providing culturally appropriate services; and conduct assessments to identify any special culturally based health care needs among their beneficiaries. QISMC applies to all prepaid health plans with Medicare or Medicaid business, so it could function as a strong stimulus for health plans to become culturally competent. Finally, CMS is having its Medicare + Choice plans implement a quality assessment and performance improvement project in 2003 that either reduces clinical disparities or implements an organizational initiative aimed at improving culturally and linguistically appropriate services.72

Because Medicaid is a state and federal program, states can and do add their own requirements related to cultural competence in their Medicaid contracts with health plans. A review of state Medicaid contracts found many requirements that promote cultural competence. Eleven states require the plan’s network to respond to cultural, racial, or linguistic needs; 28 states require services for people whose primary language is not English; and 23 states require some form of cultural competence from plans.73 Medicaid contracts for behavioral health services are somewhat more likely to contain cultural competence provisions.74

Improve Cost-effectiveness

Hiring bilingual staff or interpreters could be a cost-effective intervention, permitting more accurate medical histories to be taken and eliminating unnecessary testing.

For some health care organizations, the business case for cultural competence extends beyond increasing market share through appealing to individuals and purchasers. The fourth financial incentive for these organizations to become culturally competent is improved cost-effectiveness in caring for patients. After patients are enrolled, health plans or systems operating through any kind of capitated payment have a financial stake in providing care in a way that will limit future costs of care for enrollees. Cultural competence has the potential to change both clinician and patient behavior in ways that result in the provision of more appropriate services,43 which can be cost-effective in both the short and long run. For example, researchers have noted an association between language barriers and higher rates of diagnostic tests. Apparently, physicians compensate for difficulties in communication by ordering additional tests.30,75 Hiring bilingual staff or interpreters could be a cost-effective intervention, permitting more accurate medical histories to be taken and eliminating unnecessary testing. Culturally appropriate health education that encourages enrollees to come in for screenings or adopt healthier lifestyles provides an example of longer run cost savings. To the extent that cultural competence in health care results in prevention, earlier detection, and more appropriate treatment of illness, enrollees presumably will use fewer services. Fewer services yield greater profits for the capitated health care organization. The business case for cultural competence, therefore, extends beyond attracting new enrollees; financial rewards may result even after enrollment.

Limitations in the Business Case

Although a business case for cultural competence can be made, the financial incentives are often unclear or inconsistent. The perceived business case is therefore likely to vary depending on the market, the mission of the health care organization, and the time frame used for weighing potential adoption of cultural competence techniques. Table 1 shows how for each financial incentive, there is a limitation that weakens the business case.

Table 1.

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR CULTURAL COMPETENCE

| Incentives | Limitations |

|---|---|

| To increase enrollment | Fear of adverse selection |

| To compete for private purchaser business |

Measurement difficulty Purchasers’ tendency to respond primarily to price |

| To respond to public purchasers’ demands |

Lack of definition and monitoring/enforcement |

| To reduce costs | Emphasis on short-term cost- effectiveness Enrollee/patient turnover Inability to capture cost savings |

Views on Attractiveness of Minority Markets

It is unclear whether health care organizations as a whole have decided to seek out minority markets. Cultural competence may be an effective marketing tool for recruiting members of minority groups, and some health care organizations (such as Medicaidonly plans in cities with large minority populations) have deliberately chosen to serve this market. But historically, health care organizations have found a variety of ways to “de-market” their services or otherwise discourage care to some minority populations.76–78 They have feared, rightly or wrongly, that these populations could be more expensive to serve. In a capitated environment with non–risk-adjusted payments this would pose disadvantages from a business perspective, making some minority populations a market to avoid rather than seek out. Increased competitiveness in some markets can exacerbate this fear of adverse selection. As the size and diversity of the minority population increases, the objective business case for using cultural competence to appeal to this market also increases. Perceptions, however, can lag behind reality. Health care organizations may be slow to reorient their marketing practices toward this growing segment of the market.

Limited Employer Interest and Tools to Reward Cultural Competence and Quality

Although employers theoretically could use their clout to reward culturally competent health care organizations, the evidence suggests that employers are not systematically effectuating improvements in quality.79–82 For example, accreditation and certification guidelines could be used much more widely to make health plan purchasing decisions, but only 9 percent of employers make them a precondition83 and only 11 percent to 36 percent consider them very important criteria when selecting a plan.80,83,84 Some purchasers would be willing to reward quality, but they find it difficult to distinguish good from bad quality, while cost appears to be easier to measure.85,86

The lack of quality measurement tools is particularly acute with regard to cultural competence. The tools available to purchasers to measure health care organizations’ cultural competence are still few and very weak, and they focus almost exclusively on linguistic competence rather than broader cultural competence. Although there are many self-assessment tools and other cultural competence measures, they are designed chiefly for quality improvement purposes and do not support interorganizational comparisons. For example, a cultural competence measurement profile developed for the US Health Resources and Services Administration does not purport to be a tool for purchasers to use in making contracting decisions.87

Another example of insufficient cultural competence measures is supplied by HEDIS. As mentioned previously, HEDIS data are not reported by racial or ethnic groups, so disparities cannot be measured. The few HEDIS measures that pertain to linguistic competence have been criticized for measuring the presence but not the quality of particular services.88 Although new measures for linguistically and culturally appropriate care have been proposed,88 none have been accepted because of difficulties in operationalizing the measures and lack of evidence that good performance on the measures results in better quality health care. The use of CAHPS to promote cultural competence is limited by the fact that the survey has been only psychometrically validated in English and Spanish. Although CAHPS has been translated into other languages, its cultural appropriateness has not been tested. In sum, there is little evidence that employers are serving as catalysts for quality improvement, and even less evidence that they are pursuing cultural competence as a particular quality goal.

Vague and Seldom-Enforced Public Purchaser Provisions

Although public purchasers may be starting to mandate cultural competence in their regulations, purchasing specifications, or contracts, these mandates are not likely to have a major impact until there are more precise measures and definitions, and more attention to monitoring and enforcement. CMS does not collect data from plans participating in Medicare or Medicaid to show that they are following the QISMC cultural competence standards and guidelines. States are similarly lax. Only 8 of the 23 states that had a cultural competence requirement as part of their Medicaid contracts defined the term cultural competence.73

Neither the federal government nor the states have directed major attention to monitoring and enforcement. Although courts have required cultural competence in educational services, no published court decision has held that failure to provide language-specific or culturally competent health care services violates the Civil Rights Act.65,76 In part, that reflects the fact that the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) tends to secure voluntary compliance agreements and consent decrees from violators of the statute rather than procuring court decisions. But it is also a reflection of OCR’s limited enforcement capacity. A relatively small staff is responsible for policing the 100,000 organizations that receive funds from the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).89 A recent Institute of Medicine report on racial and ethnic health disparities recommended increased funding for OCR, stating that funding in recent years has been insufficient to investigate complaints adequately.14 Similarly, states generally have very few staff members dedicated to monitoring their Medicaid contracts, and the cultural competence provisions are a fraction of the myriad of requirements that these individuals are responsible for policing. Moreover, enforcement activity has focused on preserving the rights of people with limited English proficiency rather than other aspects of cultural competence. The issues involved in addressing individuals’ cultural needs are much more amorphous than language issues, making them weaker candidates for enforcement.

One factor complicating enforcement is that it can be difficult to pinpoint who has financial liability for compliance. The LEP individual may have a right to an interpreter, but who is responsible for paying for that service—the plan or provider? Plans may argue that the duty to ensure adequate communication rests with the provider, whereas providers retort that the plans have the resources to make these arrangements. With network health maintenance organizations being the predominant model of managed care, this question of whose duty it is to comply has huge ramifications.

Varying Calculations of Cost-effectiveness

Health care organizations are operating in ever more competitive environments, and many health care organizations have been facing financial troubles. The emphasis on solvency can stymie efforts to implement cultural competence techniques unless they are proven to pay for themselves. Even if cultural competence may be cost-effective in the long run, the ledger sheet often demands that only initiatives with shortrun payoffs be undertaken. Although some cultural competence techniques can have a short-term cost savings,75,90 most investments will require a longer time frame to show results.

Even organizations that do take a longer-term view of return on investment must cope with the fact that most of their enrollees may not be there in the long term. The theory that cultural competence will result in lower health costs and therefore a better financial picture for the health care organizations rests, in part, on a presumption of a stable enrollment base. This presumption often proves to be false. Stability is low among enrollees in employer-based insurance and much lower among Medicaid enrollees.91–95 The financial benefits of a health care organization’s cultural competence programs will not be realized if patients take their business elsewhere before savings accrue. In this respect, concerns about organizations’ willingness to invest in cultural competence mirror more general concerns voiced about prepaid health care organizations’ incentives to provide high-quality preventive care for transitory patients.78 The rationale for cultural competence is considerably weaker in highly competitive or unstable markets, in which patients frequently switch health plans and providers.

In the case of health plans, changes in financing and organization may further erode financial incentives to make investments in cost-effective cultural competence techniques. Risk and reward have largely been passed from plans to their provider networks. Even if an enrollee remains with a plan, the return on the investment may go to the provider network, not the plan. For example, a health plan seeking to reduce future costs by paying for interpreter services might find that it is bearing the cost of the additional service, but another entity (e.g., a physician group that it has capitated) will reap the financial savings resulting from the improved communications. In the cultural competence area, as in the broader area of quality identified in a recent Institute of Medicine Report,96 investments that lead to social improvements but are financially detrimental to health care organizations are not likely to be undertaken.

The cost of improving cultural competence is also more than the cost of instituting a specific intervention. Successful implementation requires an infrastructure, such as improved data systems. Culturally competent health care organizations have to know whom they serve, what their needs are, what care they are getting, and what outcomes they are experiencing. This requires systems that can track these pieces of information, and also track the factors that typically confound the study of racial and ethnic disparities, such as income, education, and employment. Even knowing the race, ethnicity, primary language, and English proficiency of enrollees is beyond the capability of most health care organizations.97–99 Factoring in the cost of updating data systems makes investments in cultural competence less attractive.

Uncertainty about the effectiveness of cultural competence techniques also raises the perceived cost. With the exception of a small set of studies on techniques related to overcoming language barriers, there has been little rigorous research evaluating the impact of particular cultural competence techniques or how to implement them successfully.43 The DHHS Office of Minority Health and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recently put together an ambitious cultural competence research agenda that could fill many of these gaps.100 Even if the research agenda is actively pursued, however, it will be several years before findings will be available. In the interim, health care organizations may perceive unproven cultural competence techniques as too great a financial risk to assume.

Summary of the Business Case and its Limitations

In sum, health care organizations have a variety of financial incentives to push them in the direction of greater cultural competence. These incentives are not always clear or consistent in the current complex financial environment. The increased emphasis on quality, however, and increased emphasis on measuring cultural competence as a part of quality, may serve to strengthen these incentives in the future. In combination, growing private and public purchaser attention to this issue may induce more health care organizations to try to become more culturally competent than they would have otherwise.

Conclusions and Implications

Major demographic shifts in the United States, coupled with increasing recognition of the role of culture and patient-provider communication in the quality of health care, underscore the need to make sure that health care organizations are culturally competent. At this point, health care organizations have some financial incentive to at least consider introduction of interventions to improve cultural competence, but these incentives are often weak, unclear, and mixed in with counterincentives. For cultural competence to reach its full potential as a means for improving quality and reducing health disparities, health care organizations will need to believe that the consequences of using cultural competence techniques will outweigh the consequences of not using them.

Our review of the financial incentives and their limitations suggests that expanded and improved use of cultural competence techniques by health care organizations requires movement in the following seven areas. Several of these echo recommendations for reducing disparities made in a recent report by the Institute of Medicine.14

Dissemination of cost-effective models of serving minority populations

Numerous health care organizations effectively serve minority groups in capitated environments. Sharing information about how they do so can change views about the attractiveness of the minority market.

Inclusion of clear cultural competence measures in quality measure sets

As noted earlier, HEDIS currently includes minimal measures of linguistic competence and no measures of cultural competence. Developing widely reported cultural competence measures would provide an important tool for public and private purchasers as well as for quality improvement efforts.

More consistent use of existing quality measures by private purchasers

Most employers do not place a high priority on NCQA accreditation and quality scores when making their purchasing decisions, and place even less attention on cultural competence as a dimension of quality. In today’s competitive environment, health care organizations have little financial incentive to improve their performance on measures that are not important to their customers. Emphasis on cultural competence measures in the common RFI currently used by many employers could be a step in that direction.

Greater specificity from government purchasers

Replacing vague requirements with precise definitions would assist monitoring and enforcement efforts. To this end, the George Washington University’s Center for Health Services Research and Policy has developed Medicaid contract specifications state officials can use to clarify expectations of culturally competent care.101

Strengthened communication and enforcement of federal and state rules regarding cultural competence

It has been suggested that OCR issue guidance on cultural competence similar to the guidance issued on people with limited English proficiency.102 Allocating additional resources to monitoring and enforcement activities would enhance the credibility that sanctions will result when health care organizations fail to comply.

Development and use of financial arrangements between plans and providers that allow plans to reap the rewards of investments in cultural competence and give providers incentive to use cultural competence techniques

If plans incur the costs of cultural competence techniques while providers reap the financial savings resulting from these techniques, these plans will be at a distinct disadvantage when competing with plans not incurring such costs. Providers’ relatively small size, however, inhibits their ability to make investments in cultural competence techniques without assistance.

Better evidence on the impact of particular techniques and the organizational structures needed to implement them

Given the ambiguity of current incentives and the difficult financial conditions faced in many markets, health care organizations that invest in development and implementation of cultural competence techniques need to be reasonably sure that they will have the desired medical and financial impact.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jan De La Mare for her research assistance, to Maggie Rutherford for her editing services, and to staff at the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Civil Rights, Brad Gray, and Jim Verdier who provided thoughtful comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Contributor Information

Cindy Brach, Center for Organization and Delivery Studies, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland.

Irene Fraser, Center for Organization and Delivery Studies, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keppel KG, et al. Trends in Racial and Ethnic-Specific Rates for Health Status Indicators: United States, 1990–98. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The President’s Initiative on Race: Health Care Rx: Access for All. Barriers to Health Care for Racial and Ethnic Minorities: Access, Workforce Diversity, and Cultural Competence. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins KS, et al. U.S. Minority Health: A Chartbook. The Commonwealth Fund; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grantmakers in Health Chartbook: Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health; Paper presented at the Grantmakers in Health; Potomac, MD. Sep 11, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baquet CR, Commiskey P. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology in Minorities: A Review. Journal of the Association of Academic Minority Physicians. 1999;10(3):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins KS, et al. Diverse Communities, Common Concerns: Assessing Health Care Quality for Minority Americans. The Commonwealth Fund; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lillie-Blanton M, LaVeist T. Race/Ethnicity, the Social Environment, and Health. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(1):83–91. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford ES, Cooper RS. Implications of Race/Ethnicity for Health and Health Care Use. Health Services Research. 1995;30(1):237–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gornick ME, et al. Effects of Race and Income on Mortality and Use of Services Among Medicare Beneficiaries. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(11):791–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609123351106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayberry RM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Access to Medical Care: A Synthesis of the Literature. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kington RS, Smith JP. Socioeconomic Status and Racial and Ethnic Differences in Functional Status Associated with Chronic Diseases. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(5):805–810. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR. Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Health. The Added Effects of Racism and Discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickens HW. The Role of Race/Ethnicity and Social Class in Minority Health Status. Health Services Research. 1995;30(1):151–162. Part II. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smedley BD, et al., editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayanian JZ, et al. Racial Differences in the Use of Revascularization Procedures After Coronary Angiography. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269(20):2642–2646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlisle DM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Cardiovascular Procedures: Associations with Type of Health Insurance. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(2):263–267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conigliario J, et al. Understanding Racial Variation in the Use of Coronary Revascularization Procedures: The Role of Clinical Factors. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(9):1329–1335. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg KC, et al. Racial and Community Factors Influencing Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Rates for all 1986 Medicare Patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267(11):1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oddone EZ, et al. Race, Presenting Signs and Symptoms, Use of Carotid Artery Imaging, and Appropriateness of Carotid Endarterectomy. Stroke. 1999;30(7):1350–1356. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson ED, et al. Racial Variation in Cardiac Procedure Use and Survival Following Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(15):1175–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins AS, et al. Race, Prostate Cancer Survival, and Membership in a Large Health Maintenance Organization. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90(13):986–990. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.13.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider EC, et al. Racial Disparities in the Quality of Care for Enrollees in Medicare Managed Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(10):1288–1294. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oddone EZ, et al. Contribution of the Veterans Health Administration in Understanding Racial Disparities in Access and Utilization of Health Care. Medical Care. 2002;40(1 Suppl):I3–I13. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derose KP, Baker DW. Limited English Proficiency and Latinos’ Use of Physician Services. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(1):76–91. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solis JM, et al. Acculturation, Access to Care, and Use of Preventive Services by Hispanics: Findings from HHANES 1982–1984. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(Suppl):11–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein JA, et al. The Influence of Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Psychological Barriers on use of Mammography. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991 Jun;32:101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner TH, Guendelman S. Healthcare Utilization Among Hispanics: Findings From the 1994 Minority Health Survey. American Journal of Managed Care. 2000;6:355–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woloshin S, et al. Is Language a Barrier to the Use of Preventive Services? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(8):472–477. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrasquillo O, et al. Impact of Language Barriers on Patient Satisfaction in an Emergency Department. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(2):82–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.David RA, Rhee M. The impact of Language as a Barrier to Effective Health Care in an Underserved Urban Hispanic Community. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 1998;65(5–6):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morales LS, et al. Are Latinos less Satisfied with Communication by Health Care Providers? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(7):409–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.06198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinman A, et al. Culture, Illness, and Care. Clinical Lessons from Anthropologic and Cross-Cultural Research. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1978;88(2):251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mackenzie ER. Cultural Competence: Essential Measurements of Quality for Managed Care Organizations. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;124(10):919–920. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-10-199605150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawson WB. The Art and Science of the Psychopharmacotherapy of African Americans. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 1996;63(5–6):301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moffic HS, Kinzie JD. The History and Future of Crosscultural Psychiatric Services. Community Mental Health Journal. 1996;32(6):581–592. doi: 10.1007/BF02251069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cross TL, et al. Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed. CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center; Washington, DC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams DL. Health Issues for Women Of Color: A Cultural Diversity Perspective. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations . State Medicaid Managed Care: Requirements for Linguistically Appropriate Health Care. Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations; Oakland, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials . Multicultural Public Health Capacity Building Pilot Projects: Final Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlandi MA, editor. OSAP Cultural Competence Series. 2d Vol. 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1995. Cultural Competence for Evaluators: A Guide for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Prevention Practitioners Working with Ethnic/Racial Communities. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tirado MD. Tools for Monitoring Cultural Competence in Health Care. Latino Coalition for a Healthy California; San Francisco: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Goal 6 Workgroup . Cultural and Linguistic Competency as a Consumer Protection Issue in DHHS. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brach C, Fraser I. Can Cultural Competency Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities? A Review and Conceptual Model. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(Suppl)(1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy S, et al. Report on Recommendations for Measures of Cultural Competence for the Quality Improvement System for Managed Care. Abt Associates Inc.; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson LD. Patients’ Rights and Professional Responsibilities: The Moral Case for Cultural Competence. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 1999;66(4):267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry . Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities. Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 47.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Secretary National Standards on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health Care. Federal Register. 2000;65(247):80865–80879. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis K, et al. Managed Care: Promises and Concerns. Health Affairs. 1994;13(4):178–185. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.4.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torres RE. The Pervading Role of Language on Health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(Suppl):S21–S25. [Google Scholar]

- 50.U.S. Census Bureau Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2000, No. 16. Resident Population by Hispanic-Origin Status, 1980 to 1999, and Projections, 2000 to 2050. 2000 http:// www.census.gov/prod/www/statistical-abstract-us.html. Accessed March 27, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Census Bureau Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2000, No. 25. Resident Population by Race, Hispanic Origin, and State: 1999. 2000 http://www.census.gov/prod/www/statistical-abstract-us.html. Accessed March 27, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen MB. Building Bridges: Marketing Managed Care to Ethnically Diverse Populations. Medical Interface. 1996;9(12):64–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardillo J. Speaking Patients’ Languages. Modern Healthcare. 1997;27(48):64–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris MS. Marketing Health Care to Minorities: Tapping an Emerging Market. Marketing Health Services. 2000;20(4):4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell A. Cultural Diversity: The Future, The Market, and The Rewards. CARING. 1995 Dec;:44–48. [AQ9] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herreria J. Marketers Target Ethnic Groups. Efforts Reflect Diversity, Managed Care Growth. Profiles in Healthcare Marketing. 1998;14(1):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang PH, Fortier JP. Language Barriers to Health Care: An Overview. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(Suppl):S5–S19. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perkins J, et al. Ensuring Linguistic Access in Health Care Settings: Legal Rights and Responsibilities. National Health Law Program; Los Angeles: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiscella K, et al. Inequality in Quality: Addressing Socioeconomic, Racial, and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(19):2579–2584. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Business Coalition on Health . 2002 V8 Core RFI, Plan Year 2003. National Business Coalition on Health; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lauer TM, et al. The InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 Part II: HMO Industry Report. InterStudy Publications; St. Paul, MN: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Civil Rights Act of 1964. Subchapter V. 42 U.S. Code §2000d.

- 63.U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division Enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—National Origin Discrimination Against Persons with Limited English Proficiency. Federal Register. 2000;65(159):50123–50125. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenbaum S, et al. U.S. Civil Rights Policy and Access to Health Care by Minority Americans: Implications for a Changing Health Care System. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(Suppl)(1):236–259. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perkins J, Vera Y. Legal Protections to Ensure Linguistically Appropriate Health Care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(Suppl):S62–S80. [Google Scholar]

- 66.White House Executive Order: Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency. Federal Register. 2000;65(159):50121–50122. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Executive Office of the President Office of Management and Budget . Report to Congress. Assessment of the Total Benefits of Implementing Executive Order No. 13166: Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency. Executive Office of the President Office of Management and Budget; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fortier JP, Shaw-Taylor Y. Cultural and Linguistic Competence Standards and Research Agenda Project. Part One: Recommendations for National Standards. Resources for Cross Cultural Health Care; Silver Spring, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 69.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Care Financing Administration Medicaid Program; Medicaid Managed Care; Final Rule. Federal Register. 2001;66(13):6227–6276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Care Financing Administration . A Profile of Medicaid: Chartbook 2000. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 71.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Care Financing Administration . Quality Improvement System for Managed Care (QISMC): Year 2000 Standards and Guidelines. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2000. http://www.hcfa.gov/quality/3a1.htm. Accessed March 29, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 72.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Medicare+Choice Organizations’ (M+CO) National Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement (QAPI) for the Years 2002 and 2003. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Baltimore: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenbaum S, et al. Negotiating the New Health System: A Nationwide Study of Medicaid Managed Care Contracts. The George Washington University Medical Center; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenbaum S, Teitelbaum J. Cultural Competence in Medicaid Managed Care Purchasing: General and Behavioral Health Services for Persons with Mental and AddictionRelated Illnesses and Disorders. The George Washington University Medical Center; Washington, DC: 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hampers LC, et al. Language Barriers and Resource Utilization in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):1253–1256. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosenbaum S, et al. Civil Rights in a Changing Health Care System. Health Affairs. 1997;16(1):90–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith DB. Addressing Racial Inequities in Health Care: Civil Rights Monitoring and Report Cards. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1998;23(1):75–105. doi: 10.1215/03616878-23-1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Block SH. Managed Care: Minorities and the Poor. Medicine and Health/Rhode Island. 1996;79(7):266–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fraser I, et al. The Pursuit of Quality by Business Coalitions: A National Survey. Health Affairs. 1999;18(6):158–165. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.6.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fraser I, McNamara P. Employers: Quality Takers or Quality Makers? Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(Suppl 2):33–52. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057002S03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyer J, et al. Theory and Reality of Value-based Purchasing: Lessons from the Pioneers. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; Rockville, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bailit MH. Ominous Signs and Portents: A Purchaser’s View of Health Care Market Trends. Health Affairs. 1997;16(6):85–88. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.6.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gabel JR, et al. When Employers Choose Health Plans: Do NCQA Accreditation and HEDIS Data Count? Commonwealth Fund; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lo Sasso AT, et al. Beyond Cost: ‘Responsible Purchasing’ of Managed Care by Employers. Health Affairs. 1999;18(6):212–223. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.6.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eddy DM. Performance Measurement: Problems and Solutions. Health Affairs. 1998;17(4):7–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dudley RA, et al. The Impact of Financial Incentives on Quality of Health Care. Milbank Quarterly. 1998;76(4):649–686. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.The Lewin Group Measuring Cultural Competence in Health Care Delivery Settings; Paper presented at the Technical Expert Panel Meeting #2; Washington DC. Nov 5, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Valadez AM. Proposed Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) Quality Measures for Language and Culturally Appropriate Care. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woloshin S, et al. Language Barriers in Medicine in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(9):724–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.David RA, Rhee M. The Impact of Language as a Barrier to Effective Health Care in an Underserved Urban Hispanic Community. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 1998;65(5, 6):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Allen HM, Jr., Rogers WH. The Consumer Health Plan Value Survey: Round Two. Health Affairs. 1997;16(4):156–166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murray BP, et al. Enrollee Satisfaction with HMOs and its Relationship with Disenrollment. Managed Care Interface. 2000;13(11):55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ellwood M. The Medicaid Eligibility Maze: Coverage Expands, but Enrollment Problems Persist. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Czajka JL. Analysis of Children’s Health Insurance Patterns: Findings from the SIPP. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carrasquillo O, et al. Can Medicaid Managed Care Provide Continuity of Care to New Medicaid Enrollees? An Analysis of Tenure on Medicaid. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(3):348–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; Washington DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bierman AS, et al. Addressing Racial and Ethnic Barriers to Effective Health Care: The Need for Better Data. Health Affairs. 2002;21(3):91–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scott T. AHRQ Task Order: Capacity to Conduct Studies on the Impact of Race/Ethnicity on the Access, Use, and Outcomes of Care; Paper presented at the First Annual Integrated Delivery System Research Network Meeting; Rockville, Maryland. Jan 28–29, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gabow P, et al. Capacity to Conduct Studies on the Impact of Race/Ethnicity on the Access, Use and Outcomes of Care; Paper presented at the First Annual Integrated Delivery System Research Network Meeting; Rockville, MD. Jan 28–29, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fortier JP, Bishop D. Developing a Research Agenda for Cultural Competence in Health Care. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, forthcoming; Rockville, MD: [Google Scholar]

- 101.George Washington University Center for Health Services Research and Policy (CHSRP) Optional Purchasing Specifications: Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Services Through Medicaid Managed Care. George Washington University Medical Center School of Public Health and Health Services; Washington, DC: http://www.hfni.gsehd.gwu.edu/~chsrp/sps/. Accessed January 25, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wong D. Analysis of DHHS OCR LEP Guidance. National Health Law Program; Los Angeles, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]