Abstract

It is not known if the mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as mitoquinone (MitoQ) can modulate oxidative stress and leukocyte-endothelium interactions in T2D patients.

We aimed to evaluate the beneficial effect of MitoQ on oxidative stress parameters and leukocyte-endothelium interactions in leukocytes of T2D patients.

The study population consisted of 98 T2D patients and 71 control subjects. We assessed metabolic and anthropometric parameters, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX-1), NFκB-p65, TNFα and leukocyte-endothelium interactions.

Diabetic patients exhibited higher weight, BMI, waist circumference, SBP, DBP, glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, triglycerides, hs-CRP and lower HDL-c with respect to controls.

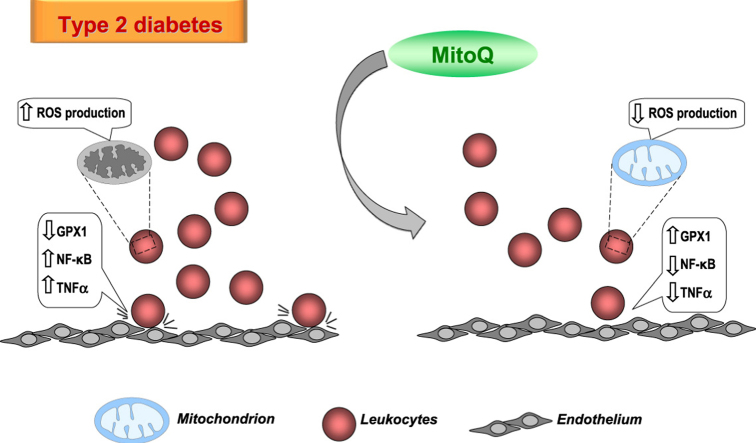

Mitochondrial ROS production was enhanced in T2D patients and decreased by MitoQ. The antioxidant also increased GPX-1 levels and PMN rolling velocity and decreased PMN rolling flux and PMN adhesion in T2D patients. NFκB-p65 and TNFα were augmented in T2D and were both reduced by MitoQ treatment.

Our findings support that the antioxidant MitoQ has an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant action in the leukocytes of T2D patients by decreasing ROS production, leukocyte-endothelium interactions and TNFα through the action of NFκB. These data suggest that mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as MitoQ should be investigated as a novel means of preventing cardiovascular events in T2D patients.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; IR, insulin resistance; LDL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TPP, triphenylphosphonium

Keywords: Leukocytes, Oxidative stress, Inflammation, Endothelium, Type 2 diabetes, MitoQ

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Mitochondrial ROS production was enhanced in diabetic leukocytes and reduced by MitoQ.

-

•

MitoQ treatment increased GPX-1 levels in T2D leukocytes.

-

•

MitoQ increased PMN rolling velocity and decreased PMN rolling flux and adhesion.

-

•

NFκB-p65 and TNFα were augmented in T2D and were both reduced by MitoQ treatment.

-

•

MitoQ should be investigated as a novel means of reducing cardiovascular risk in T2D.

1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is currently one of the foremost health concerns, especially in developed countries. T2D is related to obesity and insulin resistance (IR), but the key mechanisms relating IR and T2D in obese subjects are yet to be determined. That said, inflammation, enhanced mitochondrial ROS production and the infiltration of leukocytes into the pancreas seem to be implicated [1].

There is considerable evidence that a chronic, low-grade inflammatory response is ongoing in and actually precedes T2D and related syndromes [2], [3] and this inflammation may be due, in part, to the effects of hyperglycemia or other metabolic abnormalities on white blood cells [4]. In this sense, it has been demonstrated that there is an activation of NFκB under IR conditions [5], [6]. In this chronic inflammatory state, inflammatory cells such as leukocytes are vulnerable to and markedly damaged by hyperglycemia. In fact, these actions can contribute to the undermined innate immune function and increased risk of infection among T2D patients [7].

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment have been implicated in the etiology of IR associated with T2D [8], [9]. The pathogenesis of mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity or any diabetes-related disease is multifactorial, and can also play an important role in pancreatic β cell failure in T2D [10], [11]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that mitochondria undergo biogenesis in response to high levels of glucose, but the increased biogenesis is insufficient to accommodate a high metabolic demand [12]. In addition, obesity, which is related to T2D, is associated to increased levels of free fatty acids, inflammation, mitochondrial ROS and, therefore, oxidative stress [13].

Leukocytes, and in particular polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), constitute a critical host defence against infections associated with T2D. Furthermore, PMNs may contribute to the oxidative stress and inflammation associated with T2D. In fact, the onset of atherosclerosis involves the recruitment of leukocytes to the endothelium, a process that begins when these cells roll over the endothelial cells and come to a halt, eventually adhering firmly. In this sense, a potential role of mitochondrial dynamics and function in the maintenance of endothelial cell function in T2D has been postulated [14].

In the aforementioned context, therapies that decrease mitochondrial oxidative damage could help decrease the deleterious effects of T2D [11]. Mitoquinone (MitoQ) is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant derived from ubiquinone, and is targeted to mitochondria by covalent attachment to a lipophilic triphenylphosphonium (TPP) cation [15], [16], [17]. Due to the large mitochondrial membrane potential, this cation is accumulated within the mitochondria inside cells. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants are protective in vivo against oxidative damage in different pathologies, such as cancer, T2D, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders [18], [19], [20].

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the effect of MitoQ on oxidative stress parameters in leukocytes isolated from T2D patients, in particular the potential regulation of leukocyte-endothelial interactions and their effects on NFκB.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

98 T2D patients attending the Endocrinology and Nutrition Service of the University Hospital Doctor Peset (Valencia, Spain) and 71 controls adjusted by age and sex were enrolled in this study. T2D was diagnosed according to the American Diabetes Association's criteria. Diagnosis was confirmed when a patient fulfilled at least one of the following criteria: (1) levels of fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dl or random serum glucose ≥200 mg/dL on at least two occasions; (2) HbA1c ≥6.5%; or (3) antidiabetic medication. Subjects with any of the following conditions were excluded from the study: history of cardiovascular disease (including ischemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic disease related to cardiovascular risk); presence of morbid obesity; insulin treatment, autoimmune disease; and infectious, malignant, organic, haematological or inflammatory disease.

The study protocols were conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Doctor Peset. All participants underwent the process of informed consent required by these institutions.

Blood samples were collected in fasting conditions between 8 a.m. and 10 a.m. Subjects underwent an anthropometric and analytical assessment in which height (m), weight (kg), body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP; mmHg) were measured.

2.2. Biochemical determinations

Blood was obtained from the antecubital vein and centrifuged (1300g, 10 min, 4 °C), and biochemical determinations were performed as previously described [21]. By means of an enzymatic method, total cholesterol, levels of glucose and triglycerides were determined in serum. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) content was calculated with Friedewald's formula, and high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels were obtained using a Beckman LX20 analyzer (Beckman Corp., CA, US). Insulin levels were determined by immunochemiluminescence, and insulin resistance was estimated using the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR=[fasting insulin (μU/mL)×fasting glucose (mg/dl)]/405). Percentage of HbA1c was determined with an automatic glycohemoglobin analyzer (Arkray Inc., Kyoto, Japan) and high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels were assessed by an immunonephelometric assay.

2.3. Cell isolation

Leukocytes were isolated from heparinized blood samples that had been incubated with dextran (3%) for 45 min. Supernatant was collected, placed over Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and spun at 650g for 25 min at room temperature. Erythrocytes remaining in the pellet were lysed with lysis buffer for 5 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 240g. The leukocyte pellet was then washed and resuspended in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Sigma Aldrich, MO, US). Cells were counted with a Scepter 2.0 cell counter (Millipore Iberica, Madrid, Spain) and divided into different samples, one of which was incubated with 0.5 µM of MitoQ for 30 min, and the other with decyl-TPP in the same conditions.

2.4. Reactive oxygen species production

Mitochondrial ROS production was assessed using the fluorescent probe MitoSOX (5×10−6 mol/l, 30 min) by fluorometry using a fluorescence microscope (IX81; Olympus) coupled to the static cytometry software “ScanR” (Olympus). Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33342. Measures of fluorescence are referred to as % of control.

2.5. Western blot analysis

PMNs isolated from healthy or diabetic patients were resuspended at a density of 106 cells/mL in 3 mL of complete RPMI (RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS). For each control or patient two samples were prepared: the control sample and the treated (0.5 µM MitoQ, 30 min) sample. The non-antioxidant decyl-TPP was also used as a control compound. In the meantime, two T25 flasks with confluent HUVEC were washed twice with PBS at 37 °C. Afterwards, PMN cells (control and MitoQ/TPP) were added to the HUVEC flask and incubated and shaken for 10 min (up to 130 rpm, mimicking the leukocyte-endothelium protocol) in a horizontal shaker at a fixed temperature of 37 °C. Cells were then pelleted and stored at −80 °C for subsequent determinations. Cell pellets were lysed on ice for 15 min with cell lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 20% Glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 µm Na2MoO4, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and protein extraction was performed in the presence of a protease inhibitor mixture (10 mM NaF, 1 mM NaVO3, 10 mM PNP, 10 mM β-glycerolphosphate) [22]. Protein concentrations were determined by a BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific, IL, US) after 15 min centrifugation. Protein samples (25 μg) were resolved on 10% acrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: GPX-1 (Thermo Fisher), NFκB-p65 (Abcam), TNFα (Abcam) and Actin (Sigma). Blots were incubated with the secondary antibodies horseradish peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-mouse (Thermo Scientific) and HRP goat anti-rabbit (Millipore Iberica), and were developed for 2 min with ECL plus reagent (GE Healthcare) or Supersignal West Femto (Thermo Scientific). Visualization was by means of a Fusion FX5 acquisition system (Vilbert Lourmat, Marne La Valle´e, France). The signals were analyzed and quantified by densitometry using Bio1D software (Vilbert Lourmat) and all values were normalized to actin.

2.6. Leukocyte-endothelium interaction assay

Adhesion assays under flow conditions were carried out using a parallel plate flow chamber in vitro model as previously described [21]. Coverslips with confluent HUVEC monolayers were employed to perform the adhesion assays. These coverslips were inserted in the bottom plate of the flow chamber so that a 5×25 mm portion of the endothelial cells was exposed, and the flow chamber was mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-S) connected to a camera. Leukocyte suspensions were drawn across the HUVEC monolayer at a flow rate of 0.36 mL/min. Real time microscopic images of the flow-exposed monolayer were recorded for 5 min and examined. Leukocyte rolling velocity, rolling flux and adhesion were calculated as described elsewhere [21]. TNFα (10 ng/mL, 4 h) was used as a positive control for HUVEC, and platelet activating factor (1 µM, 1 h) for leukocytes.

2.7. Data analysis

Data analysis was performed with SPSS 17.0. The values in Tables are mean±SD. Bar graphs show mean±SEM. Comparisons between 2 groups (Table 1) were performed by a Student's t-test for normally distributed samples, and a Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed samples. Chi-Square test was used to compare proportions among groups. Data were compared with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc test. Analysis of covariance was employed to minimize the potential influence of BMI. Serum lipid and biochemical parameter changes were analyzed by means of a univariate general linear model using BMI as a covariate. Correlations were calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficient. Significant differences were considered when p<0.05.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Control | T2D | p Value | BMI-adjusted p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 71 | 98 | – | |

| Male % | 45.1 | 51.7 | 0.452 | |

| Age (years) | 57.5±8.2 | 59.1±8.3 | 0.263 | |

| Weight (kg) | 70.6±12.0 | 82.2±13.7 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8±4.0 | 30.7±4.4 | <0.001 | |

| Waist (cm) | 88.4±14.3 | 105.5±10.4 | <0.001 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 129±21 | 143±21 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74±10 | 83±15 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 91.6±12.6 | 146.8±49.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Insulin (μUI/mL) | 8.43±4.48 | 15.70±10.91 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.99±1.18 | 5.50±4.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.27±0.28 | 6.97±1.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 193.7±39.3 | 168.8±37.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 54.4±11.3 | 45.1±10.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | 121.1±31.7 | 96.2±32.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 74.0 (59.5; 97.0) | 114.0 (87.0; 157.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l) | 0.94 (0.46; 2.53) | 3.46 (1.37; 5.72) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD for parametric data or as median (25th and 75th percentiles) for non-parametric data. Means were compared by a Student's t-test for normally distributed samples and a Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed samples. Adjustments by BMI were performed by means of a univariate general linear model. A Chi-Square test was used to compare proportions among groups. HOMA-IR=fasting insulin (μU/ml) x fasting glucose (mg/dl)/405.

3. Results

We evaluated 98 T2D patients and 71 control subjects (Table 1). Diabetic patients exhibited higher weight, BMI, waist circumference, SBP, DBP, fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR and HbA1c (p<0.001) than controls. When data were adjusted by BMI, statistical differences remained unchanged. The lipid profile of diabetic subjects was characterized by higher triglyceride and lower HDL-c levels with respect to controls (p<0.001). However, due to the lipid-lowering treatment received by most of the T2D patients (65% of patients were taking statins and 6% ezetimibe), levels of total cholesterol and LDL-c were lower than in controls (p<0.001). Inflammation, measured as hs-CRP levels, was also more pronounced in diabetic patients vs controls (p<0.001). Statistical differences remained when analyses were adjusted by BMI (p<0.01).

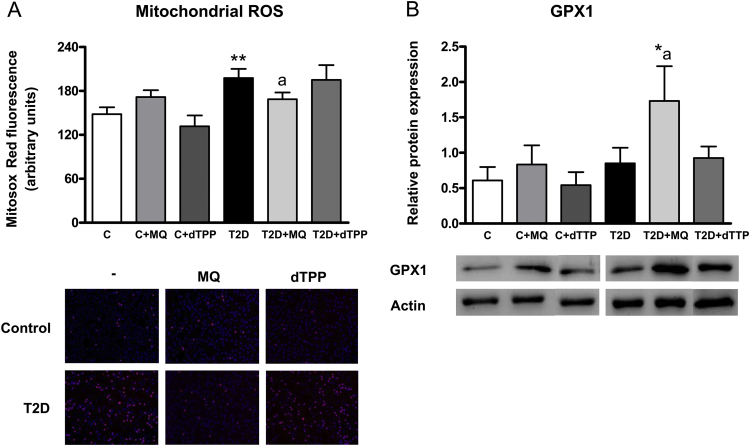

3.1. Mitochondrial ROS and glutathione peroxidase levels

Leukocytes from diabetic patients displayed enhanced levels of MitoSOX oxidation, which is consistent with an increase in mitochondrial ROS production (Fig. 1A, p<0.01). However, the mitochondrial targeted antioxidant MitoQ decreased MitoSOX oxidation in diabetic leukocytes (p<0.05) to values similar to those in controls. MitoQ did not alter MitoSOX oxidation in controls (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Levels of MitoSox oxidation in controls and T2D patients in presence and absence of MitoQ or decyl-TPP (30 min, 0.5 µM) and representative fluorescence microscopy images (B) Levels of GPX-1 (25 kDa) measured by Western blot in controls and T2D patients in presence and absence of MitoQ or decyl-TPP (30 min, 0.5 µM). * p<0.05 and **p<0.01vs control; ap<0.05 vs T2D patients.

When glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX-1) was evaluated by western blot, differences were not observed between diabetic and control subjects (Fig. 1B). The presence of MitoQ increased GPX1 levels in diabetic cell pellets (p<0.05) with respect to control and diabetic groups without MitoQ.

None of these oxidative stress parameters were affected by decyl-TPP treatment (Fig. 1A–B).

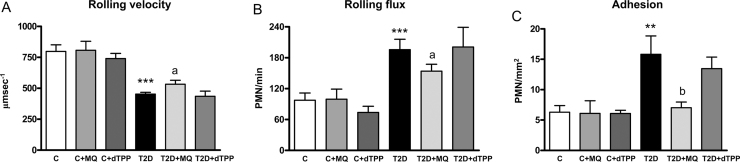

3.2. Leukocyte-endothelium interactions

When leukocyte-endothelium interactions were assessed in controls and T2D patients, a decrease in leukocyte rolling velocity (Fig. 2A, p<0.001) and an increase in leukocyte rolling flux (Fig. 2B, p<0.001) and adhesion (Fig. 2C, p<0.01) were observed in T2D patients. Those effects were reversed in the presence of MitoQ, which increased leukocyte rolling velocity (Fig. 2A, p<0.05) and reduced leukocyte rolling flux (Fig. 2B, p<0.05) and adhesion (Fig. 2C, p<0.01) in T2D patients. MitoQ had no effects in controls and decyl-TPP had no effect on leukocyte-endothelium interactions.

Fig. 2.

Leukocyte/endothelium interactions in T2D patients and control subjects in presence and absence of MitoQ or decyl-TPP (30 min, 0.5 µM). (A) PMN rolling velocity (μmsecond-1), (B) rolling flux (PMN per minute) and (C) PMN adhesion (PMN per square millimetre). **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs control. ap<0.05 and bp<0.01 vs T2D patients.

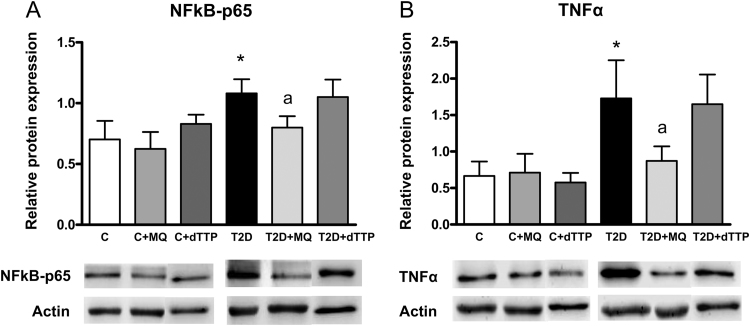

3.3. Levels of NFκB-p65 and TNFα

Diabetic patients showed an increase in NFκB-p65 levels (Fig. 3A, p<0.05). MitoQ decreased the levels of NFκB-p65 in those cells (Fig. 3A, p<0.05), showing an anti-inflammatory effect, and did not modify NFκB-p65 levels in the control condition. In addition, NFκB-p65 levels correlated negatively with GPX1 levels (p<0.05; r=−0.566) and positively with glucose levels (p<0.05; r=0.564) and PMN rolling flux (p<0.05; r=0.576).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of protein expression by Western blot of p65-NFκB (55 kDa) (A) and TNFα (23 kDa) (B) in T2D patients and control subjects in presence and absence of MitoQ or decyl-TPP (30 min, 0.5 µM). *p<0.05 vs control. ap<0.05 vs T2D patients.

In relation to TNFα levels, there was an increase in diabetic patients (Fig. 3B, p<0.05) to a similar extent as that observed with NFκB-p65 levels, and MitoQ again exerted an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing TNFα levels (Fig. 3B, p<0.05). MitoQ did not have any effect on control pellets. Furthermore, TNFα levels correlate positively with PMN rolling flux (p<0.05; r=0.580) and NFκB-p65 (p<0.001; r=0.860).

Decyl-TPP treatment did not affect NFκB-p65 or TNFα levels.

4. Discussion

In the present study we report an increase in fasting levels of glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, HbA1c and hs-CRP in T2D patients. Given that BMI was also higher in this group, we adjusted the data for this parameter, obtaining the same results.

Vascular complications and oxidative stress are features of T2D. Furthermore, oxidative stress is a key event in the immunobiology of inflammatory responses. In previous studies we have shown that oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are present in the leukocytes of T2D patients and are enhanced in patients with vascular complications [21], [23]. In the present study we have determined that increased mitochondrial ROS production occurs in leukocytes of T2D patients, suggesting that leukocyte oxidative stress and mitochondrial function are altered during long-term exposure to glucose.

Several studies have demonstrated that mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes can protect against oxidant-induced damage under hyperglicemic conditions [24], [25]. Furthermore, protecting mitochondria seems to play an important role in arteriogenesis and angiogenesis under oxidative stress conditions [26]. For these reasons, we believe that mitochondria-targeted antioxidants can modulate oxidative stress and may have beneficial effects in T2D. We have used MitoQ because this compound is biocompatible and can be administered safely in vivo with no reported toxic effects. In fact, MitoQ can prevent ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiac dysfunction [27] and also protects against endothelial dysfunction in in vivo and in vitro models [28], [29]. MitoQ has also demonstrated beneficial effects by preventing diabetic nephropathy in Ins2+/Akita J mice [18], or by modulating muscle lipid profile and improving mitochondrial respiration in obesogenic diet-fed rats [30]. However, it has been also demonstrated that TPP+ compounds such as MitoQ can disrupt mitochondrial function at concentrations frequently observed in cell culture and that this behaviour is dependent on the linker group and independent of antioxidant properties [31].

ROS may have important roles in hyperglycemia-mediated endothelial dysfunction and microvascular complications associated to IR [32], [33]. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that T2D patients have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular events, which may be related to oxidative stress [21]. In relation to this, the results of the present study show that treatment with MitoQ reduces levels of ROS and increases those of GPX1, thus exhibiting an antioxidant effect. Indeed, it has been previously demonstrated that MitoQ can reduce ROS and modulate GPX1 under oxidative stress conditions such as propionic acidemia [34].

Hypertension and atherosclerosis are inflammatory states characterized by leukocyte recruitment to arterial walls [35]. We have used an in vitro system to study this process, in which human leukocytes flow over a monolayer of human endothelial cells with a shear rate equivalent to that observed in vivo [36]. This mimics the process of rolling and adhesion that precedes inflammation in vivo, and which is essential to maintain vascular homeostasis and integrity. If these interactions are enhanced, endothelial dysfunction and vascular damage associated with many CVD can take place. In previous studies, we have demonstrated that T2D patients display features of chronic inflammation and enhanced leukocyte-endothelium interactions, and that these disturbances can be aggravated in the presence of vascular complications [21], [22], [23]. Our findings show that the inflammatory state is enhanced in T2D patients. In fact, we have witnessed an increase in PMN rolling flux and adhesion and a decrease in PMN rolling velocity by which leukocyte-endothelium interactions were induced. Interestingly, we have seen that treatment with MitoQ increases PMN rolling velocity and decreases PMN rolling flux and adhesion in the leukocytes of T2D patients, suggesting a protective cardiovascular role. Indeed, MitoQ has previously been reported to decrease ischemia-reperfusion injury in a murine syngeneic heart transplant model [37] and to decrease features of metabolic syndrome in an ATM+/-/ApoE-/- mice model [38].

NFκB is a common inflammatory factor and plays an important role in the regulation of cytokines in diabetic nephropathy [39]. Furthermore, NFκB activity is significantly increased in T2D patients with nephropathy compared to those without renal impairment [5], [40]. In line with these studies, we report that the expression of p65-NFκB is increased in T2D patients, thus highlighting the importance of this transcription factor. In addition, NFκB levels correlate positively with glucose levels, which confirms that hyperglycemia is closely associated with inflammation. In this sense, a previous study showed that inhibition of the IKKβ/NFκB pathway improves glucose tolerance in obese mice, pointing to a central role of this signaling pathway in the development of T2D [41]. We also found a negative association between p65-NFκB and GPX1, which was reported in a previous study in which lack of GPX1 promoted upregulation of p65-NFκB in mouse aortas [42]. Moreover, we have observed an increase in the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα; interestingly, treatment with MitoQ decreased the levels of NFκB and, in consequence, those of TNFα. In relation with this, it has been demonstrated that mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as MitoTempol and MitoQ can protect pancreatic β-cells against oxidative stress by decreasing NFκB activity, promoting their survival, and increasing insulin secretion in cell models of the glucotoxicity and glucolipotoxicity associated with T2D [43]. Interestingly, we have seen that both NFκB and TNFα levels correlate positively with leukocyte rolling flux, highlighting the role of these proinflammatory markers in the atherosclerotic process.

Our study reveals a potential protective role of mitochondrial targeted antioxidants in the vasculature. However, a larger cohort of patients would have provided more conclusive observations, especially with respect to the correlation studies. In addition, a control group with a similar BMI to that of our T2D patients would have strengthened our comparisons.

Overall, our findings provide a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms occurring in leukocytes/endothelium of T2D patients. They suggest that increased inflammation and oxidative stress, together with NFκB activation and increased proinflammatory cytokine TNFα, contribute to the enhanced interaction between these cells, which augments the risk of CVD. Importantly, treatment with MitoQ modulates these actions, thus preventing oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, which suggests that this compound has potential beneficial effects for preventing cardiovascular diseases in T2D.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Normanly (University of Valencia) for his editorial assistance.

This study was financed by grants PI13/01025, PI13/00073, PI15/01424, PI16/1083 and CIBERehd CB06/04/0071 by Carlos III Health Institute, PROMETEOII 2014/035 and GV/2016/169 by Ministry of Education of the Valencian Regional Government, UGP-14-93, UGP-14-95, UGP15-193 by Foundation for the Promotion of Health and Biomedical Research in the Valencian Region (FISABIO), SAF2015 67678 R by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF “A way to build Europe”). V.M.V. and M.R. are recipients of contracts from the Ministry of Health of the Valencian Regional Government and Carlos III Health Institute (CES10/030 and CP10/0360, respectively). N.D-M. is recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from Carlos III Health Institute (FI14/00125). C.B. is recipient of a postdoctoral contract from Carlos III Health Institute (CD14/00043).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are reported. The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Mittal M., Siddiqui M.R., Tran K., Reddy S.P., Malik A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:1126–1167. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickup J.C., Mattock M.B., Chusney G.D., Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1286–1292. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan B.B., Schmidt M.I., Pankow J.S., Ballantyne C.M., Couper D., Vigo A., Hoogeveen R., Folsom A.R., Heiss G. atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Low-grade systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes. 2003;52:1799–1805. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smitherman K.O., Peacock J.E. Infectious emergencies in patients with diabetes mellitus. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1995;9:53–77. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi B., Hu X., Zhang H., Huang J., Liu J., Hu J., Li W., Huang L. Nuclear NF-κB p65 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlates with urinary MCP-1, RANTES and the severity of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malin S.K., Kirwan J.P., Sia C.L., González F. Pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: role of hyperglycemia-induced nuclear factor-κB activation and systemic inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;308:E770–E777. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00510.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galkina E., Ley K. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:165–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudina S., Sena S., O'Neill B.T., Tathireddy P., Young M.E., Abel E.D. Reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity and increased mitochondrial uncoupling impair myocardial energetics in obesity. Circulation. 2005;112:2686–2695. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.554360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez-Mijares A., Rocha M., Apostolova N., Borras C., Jover A., Bañuls C., Sola E., Victor V.M. Mitochondrial complex I impairment in leukocytes from type 2 diabetic patients. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivitz W.I., Yorek M.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes: from molecular mechanisms to functional significance and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;12:537–577. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green K., Brand M.D., Murphy M.P. Prevention of mitochondrial oxidative damage as a therapeutic strategy in diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:S110–S118. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards J.L., Quattrini A., Lentz S.I., Figueroa-Romero C., Cerri F., Backus C., Hong Y., Feldman E.L. Diabetes regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and fission in neurons. Diabetologia. 2010;53:160–169. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1553-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dandona P., Aljada A., Chaudhuri A., Mohanty P., Garg R. Metabolic syndrome - a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation. 2005;111:1448–1454. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J.A., Wei Y., Sowers J.R. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Circ. Res. 2008;102:401–414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James A.M., Sharpley M.S., Manas A.R.B., Frerman F.E., Hirst J., Smith R.A.J., Murphy M.P. Interaction of the mitochondria targeted antioxidant MitoQ with phospholipid bilayers and ubiquinone oxidoreductases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:14708–14718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy M.P., Smith R.A.J. Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations. Annu. Rev. Pharm. 2007;47:629–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith R.A.J., Adlam V.J., Blaikie F.H., Manas A.R.B., Porteous C.M., James A.M., Ross M.F., Logan A., Cocheme H.M., Trnka J., Prime T.A., Abakumova I., Jones B.A., Filipovska A., Murphy M.P. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants in the treatment of disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1147:105–111. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chacko B.K., Reily C., Srivastava A., Johnson M.S., Ye Y.Z., Ulasova E., Agarwal A., Zinn K.R., Murphy M.P., Kalyanaraman B., Darley-Usmar V. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy in Ins2(+/)-(AkitaJ) mice by the mitochondria-targeted therapy MitoQ. Biochem. J. 2010;432:9–19. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu C., Zhang D.W., Whiteman M., Armstrong J.S. Is antioxidant potential of the mitochondrial targeted ubiquinone derivative MitoQ conserved in cells lacking mtDNA? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008;10:651–660. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apostolova N., Victor V.M. Molecular strategies for targeting antioxidants to mitochondria: therapeutic implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015;22:686–729. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez-Mijares A., Rocha M., Rovira-Llopis S., Bañuls C., Bellod L., De Pablo C., Alvarez A., Roldan-Torres I., Sola-Izquierdo E., Victor V.M. Human leukocyte/endothelial cell interactions and mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic patients and their association with silent myocardial ischemia. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1695–1702. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rovira-Llopis S., Bañuls C., Apostolova N., Morillas C., Hernandez-Mijares A., Rocha M., Victor V.M. Is glycemic control modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress in leukocytes of type 2 diabetic patients? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;21:1759–1765. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovira-Llopis S., Rocha M., Falcon R., de Pablo C., Alvarez A., Jover A., Hernandez-Mijares A., Victor V.M. Is myeloperoxidase a key component in the ROS-induced vascular damage related to nephropathy in type 2 diabetes? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19:1452–1458. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munusamy S., MacMillan-Crow L.A. Mitochondrial superoxide plays a crucial role in the development of Mitochondrial dysfunction during high glucose exposure in rat renal proximal tubular cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowluru R.A., Kowluru V., Xiong Y., Ho Y.S. Overexpression of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in mice protects the retina from diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai S., He Y., Zhang H., Yu L., Wan T., Xu Z., Jones D., Chen H., Min W. Endothelial-specific expression of mitochondrial thioredoxin promotes ischemia-mediated arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:495–502. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adlam V.J., Harrison J.C., Porteous C.M., James A.M., Smith R.A., Murphy M.P., Sammut I.A. Targeting an antioxidant to mitochondria decreases cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2005;19:1088–1095. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3718com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esplugues J.V., Rocha M., Nuñez C., Bosca I., Ibiza S., Herance J.R., Ortega A., Serrador J.M., D'Ocon P., Victor V.M. Complex I dysfunction and tolerance to nitroglycerin: an approach based on mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants. Circ. Res. 2006;99:1067–1075. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250430.62775.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham D., Huynh N.N., Hamilton C.A., Beattie E., Smith R.A., Cochemé H.M., Murphy M.P., Dominiczak A.F. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ10 improves endothelial function and attenuates cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2009;54:322–328. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coudray C., Fouret G., Lambert K., Ferreri C., Rieusset J., Blachnio-Zabielska A., Lecomte J., Ebabe Elle R., Badia E., Murphy M.P., Feillet-Coudray C. A mitochondrial-targeted ubiquinone modulates muscle lipid profile and improves mitochondrial respiration in obesogenic diet-fed rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2016;115:1155–1166. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515005528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reily C., Mitchell T., Chacko B.K., Benavides G., Murphy M.P., Darley-Usmar V. Mitochondrially targeted compounds and their impact on cellular bioenergetics. Redox Biol. 2013;(1):86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giacco F., Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ. Res. 2010;107:1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prieto D., Contreras C., Sánchez A. Endothelial dysfunction, obesity and insulin resistance. Curr. Vasc. Pharm. 2014;12:412–426. doi: 10.2174/1570161112666140423221008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallego-Villar L., Pérez B., Ugarte M., Desviat L.R., Richard E. Antioxidants successfully reduce ROS production in propionic acidemia fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;452(3):457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Victor V.M., Rocha M., Bañuls C., Alvarez A., de Pablo C., Sanchez-Serrano M., Gomez M., Hernandez-Mijares A. Induction of oxidative stress and human leukocyte/endothelial cell interactions in polycystic ovary syndrome patients with insulin resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96(10):3115–3122. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dare A.J., Logan A., Prime T.A., Rogatti S., Goddard M., Bolton E.M., Bradley J.A., Pettigrew G.J., Murphy M.P., Saeb-Parsy K. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant MitoQ decreases ischemia-reperfusion injury in a murine syngeneic heart transplant model. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2015;34:1471–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercer J.R., Yu E., Figg N., Cheng K.K., Prime T.A., Griffin J.L., Masoodi M., Vidal-Puig A., Murphy M.P., Bennett M.R. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ decreases features of the metabolic syndrome in ATM+/-/ApoE-/- mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mezzano S., Aros C., Droguett A., Burgos M.E., Ardiles L., Flores C., Schneider H., Ruiz-Ortega M., Egido J. NF-kappaB activation and overexpression of regulated genes in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2004;19:2505–2512. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann M.A., Schiekofer S., Isermann B., Kanitz M., Henkels M., Joswig M., Treusch A., Morcos M., Weiss T., Borcea V., Abdel Khalek A.K., Amiral J., Tritschler H., Ritz E., Wahl P., Ziegler R., Bierhaus A., Nawroth P.P. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with diabetic nephropathy show increased activation of the oxidative-stress sensitive transcription factor NF-kappaB. Diabetologia. 1999;42:222–232. doi: 10.1007/s001250051142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benzler J., Ganjam G.K., Pretz D., Oelkrug R., Koch C.E., Legler K., Stöhr S., Culmsee C., Williams L.M., Tups A. Central inhibition of IKKβ/NF-κB signaling attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 2015;64:2015–2027. doi: 10.2337/db14-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis P., Stefanovic N., Pete J., Calkin A.C., Giunti S., Thallas-Bonke V., Jandeleit-Dahm K.A., Allen T.J., Kola I., Cooper M.E., de Haan J.B. Lack of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim S., Rashid M.A., Jang M., Kim Y., Won H., Lee J., Woo J.T., Kim Y.S., Murphy M.P., Ali L., Ha J., Kim S.S. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants protect pancreatic β-cells against oxidative stress and improve insulin secretion in glucotoxicity and glucolipotoxicity. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2011;28:873–886. doi: 10.1159/000335802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]