Abstract

In the context of dramatic changes in family organization, this research analyzes time shared with the family (partner and children) among couples with young children in Spain. The main purpose of the paper is to analyze the differences in the roles of mothers and fathers in dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples. For this purpose, we use information derived from the question “with whom the activity is done,” which is included in the enumeration form of the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. The availability of time-use diaries for all the members of a household allows the use of the couple as a unit of analysis. The descriptive and multivariate results show that mothers spend more time with children than fathers do and that the employment-status variables are the most determining factors. Gender-balanced couples have lower differences in the time that fathers and mothers spend on activities with their children. However, the differences remain high, and mothers are still the main caregivers in the household. These findings apply to a specific context characterized by weak policies related to balancing family and work and by the persistence of a division of roles in the couple with some resemblances to the traditional model, especially in the role that considers mothers the main caregivers.

Keywords: Family time, time use, dual-earner couples, Spain

Introduction

Family organization has changed dramatically in recent decades. The decline of the male breadwinner model and the predominance of a new model in which both parents are employed involve a new organization of tasks and a different allocation of time between both parents (Bianchi et al. 2006: Gershuny, 2000). Although the division of time is not completely egalitarian, the differences in time allocation between men and women have decreased considerably (Sayer 2005; Ajenjo and Garcia 2014). Family time is also affected by the new organization of paid and unpaid duties. The increase of paid hours reduces the time spent with a partner and provides less availability to spend with children (Glorieux et al. 2011). Family time is considered an important value to an individual, and its availability is considered a good indicator of well-being and it is also a good input for children’s development (Hallberg and Klevmarken 2003; Pleck, 2010). Time pressures derived from the new employment arrangements of the household have a negative effect on family time and as a consequence, on individual well-being (Kingston and Nock, 1987; Presser, 2003).

Besides labor constraints, attitudes also matter for family time. It has been widely documented that couples whose members have more egalitarian values have a more symmetrical allocation of time (Meil 2005). Dual-earner couples, couples in which the mother reaches higher educational attainment and cohabiting couples are associated with more egalitarian behaviors (Gonzalez and Jurado 2009; Baxter 2005; Batalova and Cohen 2002; Ajenjo and Garcia 2011). Regarding family time, it generally seems that having characteristics associated with more egalitarian behaviors (dual earner, higher education, cohabitors) predicts a greater availability of time and, as a result, a higher participation rate of fathers with their children (including the share of time that fathers spend alone with their children) (Pleck 2010; Gracia 2014; Garcia 2013; Gimenez Nadal et al. 2012).

In this context of large changes in family organization, this research analyzes the time shared with the family (partner and children) among couples with young children in Spain. Spain is characterized by a later generalization of the dual-earner family model, and some norms and behaviors of the traditional model remain (Sevilla Sanz et al. 2010). At the same time, prioritizing family and family balance is difficult because of the particularly long working schedules (Gutierrez Domenech, 2010). The main purpose of this paper is to analyze the differences in the roles of mothers and fathers in dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples. Dual earner couples are becoming more predominant and the preferred arrangement for couples (Garcia Roman, 2013; Dema, 2006). However, it is crucial to explore to what extent changes observed in labour market, specially related with the generalization of female employment, are actually being reflected in the allocation of household and care activities.

We base our research on data from time-use surveys, which are the most reliable source of information to study an individual’s allocation of time and to generate further understanding of economic decision-making processes (Robinson & Godbey, 1997; Sevilla, 2013). Through diaries of activities, information regarding all the activities conducted in 24 hours is collected with other sociodemographic information and information that concerns the activities undertaken. “With whom?” the activity is done is a common question in time-use diaries. Several scholars have used this information to conduct studies on family time in some societies (Kingston and Nock 1987, Lesnard 2008, Gutierrez Domench 2010, Sevilla Sanz et al. 2010, Bianchi et al. 2006).

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, we review the previous empirical evidence on family time from a comparative perspective and discuss the limitations of the theory on housework division. Second, we present our research hypotheses. Third, we describe the data and the methods used. In the results section, we analyze the most common activities with the spouse and children and compare the differences between dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples. We also examine the main factors that explain the amount of family time for each type of couple and the differences between fathers and mothers in dual-earner couples. These results are discussed in the final section.

Our findings show that mothers spend much more time with their children than fathers do, and even in more egalitarian couples, this difference persists. A father’s time with his children is affected more by the mother’s schedule, whereas a mother’s time with her children is less responsive to the employment of the father. In this sense, a mothers’ time with her children seems more “obliged,” whereas a fathers’ time may be considered a substitution for the mother’s time when she is working. The traditional allocation of time that gives the mother the role of the main caregiver is still strong in the family arrangement of couples in Spain. As other studies suggested with previous data, traditional values are still predominant in the Spanish society (Sevilla Sanz et al, 2010). Changes are moving slowly and the scarcity of policies of balancing work and family makes them more difficult. Balancing the traditional role (main caregiver) and the new role (member of a dual-earner unit) may have a negative effect on mothers’ career that still maintain family responsibilities as a priority.

Background

The importance of family time

Sharing time with close relatives is considered positive and a sign of well-being in society (Hellberg and Klevmarken 2003; Flood and Genadek 2013; Bitman and Wajcman 2000; Voorspostel et al. 2009). Time with the spouse is considered a sign of good marital quality (Glorieux et al. 2011). New parents are expected to be active in parenting and in spending as much time as possible with their children (Bianchi et al. 2006; Gonzalez et al. 2013, Gracia 2014). Therefore, in general, family time is considered a good value for the individuals concerned (Daly 2001), although sometimes, it will be a source of moments of conflict, discussions and tension (Hochschild 1997). Although the interpretation of time together differs between men and women, with men declaring more time together (Gager and Sanchez 2003; Bernard 1982; Flood and Genadek 2013), both men and women want to spend more time together. However, men demand a higher quantity of time together, whereas women want a higher quality of time together (Roxburgh 2006).

The importance of family time is related not only to the current well-being of the individual but also to the future development of children. The time that parents spend with their children is considered a good input for child development (Pleck 2010; Gracia 2014). Parents’ involvement is important in terms of caring and time spent in routine activities; it is also important for the time that is devoted to more interactive activities, and there is a positive relation between an increased involvement of parents and child development (Zick et al. 2001). Generally, when children are younger, they demand more basic activities, whereas older children require more interactivity (Waldfogel 2006; Gracia 2014, Roeters et al. 2009).

Differences in the amount of family time have also been observed across other sociodemographic characteristics. Traditional gender role attitudes favor the separation of the male and female spheres and suppose more separate lifestyles and less time together (Kalmijn and Bernasco 2001). Married couples also have less social participation (Gerstel and Sarkisina 2006; Dew 2009), whereas cohabiters tend to spend more time on independent activities (Glorieux et al. 2011; Kalmijn and Bernasco 2001). Couples with higher education usually work less in jobs with non-standard working hours and are more egalitarian – two factors that are positively correlated with more family time (Hammermesh 2002; Glorieux et al. 2011).

The amount of time is not the only important factor; the quality of time is also important. Sometimes, family time occurs under time pressure. Multitasking, when more than one activity is performed at the same time, is a strategy used to spend more time with the family when there is less availability of time. Multitasking is associated with an increase in negative emotions, stress, psychological distress and work-family conflict for mothers (Offer and Schneider 2011). The consequences of multitasking are less evident for fathers. In this sense, the presence of children in unpaid work activities is more common for mothers, which is a clear sign that in the majority of cases, women must perform other activities while they are taking care of children (Kingston and Nock 1987; Gershuny 2000; Sevilla-Sanz et al. 2010).

In general, the most common family time activities are eating meals and participating in media activities (including watching TV) (Sevilla-Sanz et al. 2010, Glorieux et al. 2011, Garcia 2013). Watching TV is the most common activity for fathers in the presence of children. Mothers’ main activities in the presence of children are childcare and household tasks (Glorieux et al. 2011). Travel, voluntary activities and leisure are also common activities with the family, but the proportion of time is greater when the activity is performed alone. The presence of children reduces joint leisure time, especially if the children are young.

Although there is a significant consensus regarding the importance of family time and its increase in recent decades, the evidence concerning time alone with the spouse is more contradictory. Some authors have found that time alone with the spouse has decreased in recent decades, especially among dual-earner couples (Dew 2009), whereas other authors have found that time with the spouse has not decreased in recent decades and may have even slightly increased (Voorspostel et al. 2009). Dual-earner couples must combine two working schedules and the desire to spend more time with their children, which gives them less time to spend alone with their partners (Flood and Genadek 2013, Barnet-Verzat et al. 2009). Couples prefer to spend time together and seek to maximize this time when they try to synchronize their schedules, but they are forced to desynchronize their schedules to minimize paid childcare (Hammermesh 2002). Working non-standard hours is a solution to balance the needs of work and family, but it has a negative effect on the time spent with the spouse (Wight et al. 2008, Kingston and Nock 1987; Presser 2003). The major difference is observed when children are present. The presence of children reduces joint leisure time for couples and even more when the children are young (Barnet-Verzat et al. 2009). The reduction is greater in weekdays, and couples try to compensate with designated time during weekends and non-working days (Flood and Genadek 2013, Glorieux et al. 2011, Dew 2009).

Gender differences in parenting

The desire to spend more time with family has increased, along with a higher incidence of couples in which both members are in the labor market. Because both members are employed, this supposes a new organization of the household and more difficulties in balancing work and family life; consequently, there are more constraints on the amount and quality of family time (Lesnard 2008). Couples must address two realities that pull them in opposite directions. Both members are employed, and they want to spend more time with close relatives. Thus, they must coordinate their schedules because they want to have time for their partner and children (Sullivan 1996). The main pattern observed in dual-earner couples is that they spend more time with their children, but they have less time with their spouse (Flood and Genadek 2013, Glorieux et al. 2011).

Although the new organization of the household has led to more time pressure and constraints, time with children has increased in recent decades (Bianchi et al. 2006). Mothers continue to spend a large portion of their time with children, whereas fathers are more involved in activities that concern children, especially the activities that are less routine and more interactive (Gracia and Bellani 2010, Craig and Mullan 2011; Baizan et al. 2013). The amount of time fathers spend with their children is positively correlated with the mothers’ employment and wages, and in dual-earner couples, fathers engage in more childcare and other activities with their children (Gutierrez Domenech 2010; Bloemen and Stancanelli 2014). When mothers work non-standard hours, fathers are more likely to participate in childcare than in other dual-earner couples (Presser 1988). Mothers’ time devoted to childcare is less affected by the fathers’ wages or working time (Bloemen and Stancanelli, 2014)

Context of our study: Spain

Our research is conducted in the context of Spain. The substantial incorporation of women in the labor market occurred later than in other western European countries, and until the beginning of this century, the male-breadwinner model was predominant in Spanish families (Alberdi 1999). Traditional norms were more common, and although in recent decades, there has been a modernization of Spanish society, the gender role that obligates mothers to provide care is well established (Gimenez-Nadal and Sevilla, 2014; Sevilla Sanz et al. 2010; Gimenez Nadal et al. 2012; Dema 2005; Dominguez-Folgueras and Castro-Martin 2008, Esping-Andersen 2009). Although most couples claim to prefer the dual-earner couple model after the transition to the first child, women usually reveal a greater predisposition to adapt their schedules to meet childcare needs (Abril et al. 2015, Dominguez-Folgueras 2015).

The policies regarding the balance of work and family are weak, and the support of families has been an important factor in helping working families (Lewis, 2009; Baizan et al. 2013). The labor market is characterized by strong rigidity in working arrangements, and employed parents report little control over their work schedules. The commonly employed “split-shift” working schedule supposes a large break for lunch and the termination of work late in the evening (Gutierrez Domenech, 2010; Gracia and Kalmijn, forthcoming).

Hypotheses

Considering the previous research on family time and the context of Spain, we formulate the following hypotheses for this study according to two aspects, namely, general family time and specific parenting time.

H1: Family time: Differences between dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples. The predominance of the new model of couples in which both members are in the labor market leads to a new organization of the household that also affects time with the spouse and children.

-

a)

Male-breadwinner couples have more family time, which is concentrated in time with children rather than in time with the spouse. Male-breadwinner couples do not have to deal with the constraint of two work schedules, which provides more time availability. In dual-earner couples fathers’ involvement in childcare cannot compensate for the greater participation of mothers in the labor market.

-

b)

Differences are expected to be greater in less routine activities than in activities that are essential and difficult to postpone. For the same reason, differences will also be smaller during weekends, when the constraints of work are usually lower.

H2: Parenting: Differences by gender. Although there have been advances in recent decades, gender inequality in parenting is still prevalent.

-

a)

Greater mothers’ time than fathers’ time in both types of couples. Gender differences will persist even when we control for other characteristics linked with more egalitarian values in the couple (dual-earner couples, cohabiter couples, couples with higher-educated women, and younger couples).

-

b)

Less quality of time for mothers. A mother’s activities with her spouse and children will be more contaminated by other activities, such as unpaid work, which is a sign that the quality of family time will differ between both members of the couple. We also expect differences in the activities that are conducted alone with the spouse, with the spouse and children and with fathers and mothers alone with their children.

-

c)

Higher incidence of the mother’s schedule than the father’s schedule. A father’s time with his children is expected to be greater when the mother is at work. A mother’s time depends less on the work schedule of the father. A father’s time with his children is considered to be a substitution for the mother’s time when she is at work. Mothers are still the main caregivers, and time with their children is less dependent on the characteristics of the household and the couple.

These hypotheses will be tested according to Spanish social and institutional contexts. Therefore, we assume that while differences in family time between dual earner and male-breadwinner couples (H1) will follow the similar patterns observed in other countries where dual earner couples also have generalized, gender differences in parenting (H2) and can present stronger specificities in our study. Since parenting is driven by socially acceptable gender norms in caregiving and affected by public policies on work and family life balance, the Spanish context is not expected to favor the overcoming of gender differences of fathers and mothers. The article will contribute to the existing literature with new evidence from this specific social and institutional setting.

Data and methods

We use data from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. This is the second edition of the time use survey conducted by the National Statistical Institute and follows the guidelines of Eurostat (INE 2011). The information was collected through a diary of activities where the respondents report their activities for 24 hours in 10-minute intervals. For each interval, all members of the household aged 10 years and older reported their main activity, secondary activity, location, use of Internet and persons with whom the activity was conducted. In addition, sociodemographic information including all the members of the household was collected. The sample comprises 9,541 households with 25,896 individuals.

The availability of time use diaries for all members of a household allows the use of the couple as a unit of analysis, which is crucial for comparing the role of mothers and fathers and the dynamics between the parenting times of the two. We selected couples with children younger than 10 years in the household where both members are between 20 and 49 years old. According to the work status (employed or not employed)1 of the members, the couples are classified into the following 4 different types: dual-earner couples where both members work; male-breadwinner couples; female-breadwinner couples; and couples where no member is working. In this study, we use only the most representative couples, namely, dual-earner couples, which are the main object of analysis, and male-breadwinner couples for comparative reasons. These types represent 75% of the couples. The final sample included 1,177 couples.

Using the information regarding which members of the family are present during the activity, we compute the following 4 types of family time: spousal time (only the partners are present); parent time (both partners and children are present); father time (father with his children without his partner); and mother time (mother with her children without her partner). Questions concerning “with whom” the activity is performed were not asked for some personal care activities, and we do not consider paid work activities because the time together at work has some particularities that differ from the meaning of family time that we want to study. Finally, we group family time into several categories, namely, unpaid work, travel, meals, leisure, media, care and odd jobs. Although there are 2 measures of spousal time and parent time for each couple (one according to information from the father and one according to information from the mother), we compute the mean of both estimates to have only one measure for each couple. The results for fathers and mothers were computed separately, but the main results are the same. Table 2 shows the total for each category of family time for fathers and mothers according to the type of couple. To simplify the number of regressions and make the explanation of the results easier, we will use the mean.

Table 2.

Measure of family time according to the type of couple for fathers, mothers and mean of both

| Time | Type of couple | Father | Mother | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Spousal time | DE couples | 85 | 80 | 83 |

| MB couples | 90 | 83 | 87 | |

| Parents's time | DE couples | 203 | 209 | 206 |

| MB couples | 253 | 261 | 257 | |

| Father time | DE couples | 84 | - | - |

| MB couples | 27 | - | - | |

| Mother time | DE couples | - | 177 | - |

| MB couples | - | 318 | - | |

Source: Own calculations from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. INE

The analysis comprises 3 different parts. The first part shows the main activities shared with the partner and children. We also compare the differences between dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples and between weekdays and weekends in a descriptive analysis of the mean minutes of family time devoted to each activity considered.

In the second part, we analyze the factors to explain the amount of each family time. In this case, we apply a general linear model where the dependent variables are the four types of family time. For the explanatory variables, we selected the characteristics that the previous literature on the topic considers more relevant in explaining the differences in the time use of the couples. These variables are the following:

- Type of couple according to the working status of its members, i.e., dual earner and male breadwinner;

- Age of the mother, i.e., 20-34 and 35-49;

- Educational attainment of the mother, i.e., primary or less, secondary, and university;

- Type of union, i.e., cohabitation or marriage;

- Day of the week when the information was collected;

- Age of the youngest child, i.e., 0-3, 4-9; and

- Availability of domestic service.

Younger couples who are cohabiting, who have a higher education and in which both members are employed usually show more egalitarian behavior (Gonzalez and Jurado 2009; Baxter 2005; Batalova and Cohen 2002; Ajenjo and Garcia 2011). The allocation of time is also more egalitarian during weekends. Controlling by the age of the children, we suppose that when children are younger, they require more attention, and fathers and mothers will differently adapt their schedules to these needs. Although it is not a direct sign of equality in the couple, the availability of domestic service reduces the time spent on housework activities, and consequently, the gender gap decreases.

Other variables such as the educational attainment of the father or the income of the household have been considered but are not included in the final model because they have low significance or because their effect is the same as the other variables that are already included.

In the third part, only dual-earner couples and family time activities between 6 and 12 a.m. are selected. The objective of this third part is to analyze which characteristics are more important to explain the time of fathers and mothers alone with their children. We apply two different logistic regression models where the dependent variables are father time and mother time. In every 10-minute interval where the individual performs some family activity, the dependent variable takes the value of 1 if the father/mother is alone with the children and takes 0 otherwise. In this analysis, we introduce a new variable to measure if the partner is at work. For father time, the variable takes the value of 1 if the mother is working. In the second model, the variable takes the value of 1 if the father is working.

Results

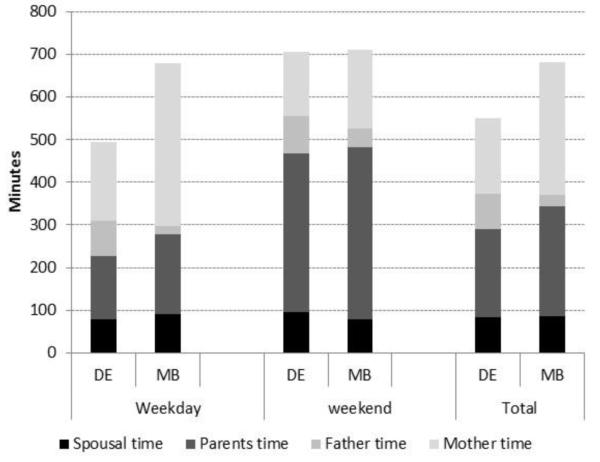

We begin this section with a comparison of the distribution of family time of dual-earner (DE) and male-breadwinner (MB) couples, both in absolute terms and controlling for the relevant variables that are associated with time use. Table 3 shows the family time distribution in minutes for different activities and according to the type of couple, and it distinguishes between dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples. We can also observe the differences between weekdays and weekends. Figure 1 summarizes the total time for each type of family time by day of the week and type of couple. The estimates clearly show that the total family time is greater for MB couples, with the differences concentrated during the weekdays. Total time is the same in both types of couples on the weekends where time with the spouse and children increases, and total time supposes a reduction in time of mothers alone with their children. During the weekdays, however, the mothers in MB couples spend a significant amount of time alone with their children (more than 6 hours), which is more than double the amount spent by the mothers in DE families. The time alone of mothers with their children during weekdays is the main difference between MB and DE couples because in MB couples, mothers are definitely the main responsible parent of the children. The differences observed for parent time are smaller (40 minutes during weekdays and 30 minutes during weekends), whereas the differences for time alone with a spouse are not significant. Father time is higher in DE couples (approximately 1 hour for the entire week), which confirms that DE couples are more egalitarian, and this increased father time implies a greater responsibility of fathers in caring for their children.

Table 3.

Family time in selected activities for dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples. Couples with children 0-10 years old at home (mean in minutes)

| Dual-earner couples |

Male-breadwinner couples |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family time | Activity | weekday | weekend | total | weekday | weekend | total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Spousal time | Unpaid work | 10 | 12 | 11 | 16 | 11 | 15 |

| Travel | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Meals | 18 | 21 | 19 | 16 | 14 | 15 | |

| Leisure | 7 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | |

| Media | 31 | 34 | 32 | 33 | 40 | 35 | |

| Care | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Odd jobs | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| Total | 78 | 96 | 83 | 90 | 80 | 87 | |

| Parents' time | Unpaid work | 20 | 43 | 26 | 23 | 40 | 28 |

| Travel | 10 | 43 | 18 | 12 | 45 | 23 | |

| Meals | 37 | 90 | 51 | 50 | 98 | 65 | |

| Leisure | 20 | 75 | 34 | 26 | 90 | 47 | |

| Media | 20 | 47 | 27 | 32 | 51 | 38 | |

| Care | 38 | 60 | 44 | 38 | 62 | 46 | |

| Odd jobs | 4 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 10 | |

| Total | 148 | 372 | 206 | 188 | 402 | 257 | |

| Father time | Unpaid work | 8 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Travel | 14 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Meals | 8 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Leisure | 9 | 15 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 3 | |

| Media | 7 | 14 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 4 | |

| Care | 35 | 33 | 35 | 8 | 21 | 13 | |

| Odd jobs | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 83 | 86 | 84 | 19 | 45 | 27 | |

| Mother time | Unpaid work | 36 | 24 | 33 | 98 | 44 | 80 |

| Travel | 28 | 12 | 24 | 44 | 8 | 33 | |

| Meals | 16 | 15 | 16 | 31 | 17 | 26 | |

| Leisure | 11 | 29 | 16 | 27 | 21 | 25 | |

| Media | 7 | 10 | 8 | 22 | 16 | 20 | |

| Care | 79 | 55 | 73 | 149 | 72 | 124 | |

| Odd jobs | 7 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 10 | |

| Total | 186 | 151 | 177 | 382 | 183 | 318 | |

Source: Own calculations from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. INE

Figure 1. Family time by the type of time, day of the week and type of couple.

Source: Own calculations from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. INE

Time alone with the spouse doesn’t present significant differences between DE and MB couples. Nevertheless, DE couples spend more time together during weekends when they share more time during meals and leisure activities.

Nevertheless, even when DE couples are considered more egalitarian than MB couples, the time fathers spend with their children is much less than the time that mothers spend. The differences observed in MB couples are significant, and fathers’ time with children during weekdays is almost inexistent. This fact can be explained because only the father is employed; therefore, in this type of couple, there is a clear division of roles. Less rational is the explanation for dual-earner couples in which both members are employed. The differences decrease, but they are still approximately 1 hour and a half for the entire week.

Regarding the activities, although the main activities with the partner and children are similar for both types of couples, they differ in the amount of time spent on each activity. The differences between weekdays and weekends are also observed. Meals, caring and media activities are the most important family activities. Media is the most common activity alone with the partner. Couples of both types spend very little time performing other activities alone with their partners. Meals more commonly bring the spouse and children together, whereas caring activities are shared with children alone as a family. Caring is the main activity of mothers who are alone with their children, especially in MB couples, spending an average of 2 hours per day during the entire week. Mothers also report doing housework in the presence of a child, which is a sign of the multitasking that they must perform when they are caring for children. Again, this finding is clearer for MB couples, which can give an idea about the quality of time with children. Presence of children during unpaid work may be less interactive than during other activities and it suggests that part of the huge amount time with children in male-breadwinner couples is only supervising. Leisure with the spouse and children is also very common during weekends.

Table 4 shows the MANOVA models that use significant characteristics to explain the differences in family time. The coefficients can be interpreted as the net difference between the category and the reference category. In general, the characteristics that involve more egalitarian values are associated with more egalitarian behavior in family time (which is defined as couples with increased father time and less difference between the total time spent by fathers and mothers). In both cohabiting couples and couples with a mother with a university degree, fathers are more involved, and the time of mothers who are alone with their children is lower for less-educated mothers. As shown in Table 1, DE couples are less often married than MB couples, and their educational attainment is higher, with 43% of mothers being tertiary educated. Therefore, the differences between these two groups of couples may be attributed not only to the time availability of the parents but also to a more favorable composition. However, the multivariate results confirm the differences observed between DE and MB couples that we observed in the descriptive statistics presented in Table 3: the differences between mother time and father time are lower in DE couples than in MB couples. Although fathers spend 53 minutes more time alone with their children in DE couples than in MB couples, mother time in DE couples is estimated to be 2 hours and 25 minutes lower than in MB couples.

Table 4.

MANOVA Family time. Dual-earner and male-breadwinner couples with children at home (minutes per day)

| Conjugal time | Parents time | Father time | Mother time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of couple (ref=male breadwinner) | Dual earner | −8.475 (6.194) |

−32.197** (11.385) |

52.530*** (6.253) |

−144.883*** (11.850) |

| Union status (ref=married) | Cohabiter | −15.358 (9.478) |

−27.923 (17.421) |

22.472* (9.568) |

10.979 (18.133) |

| Eduational attainment of the mother (ref=University) |

Primary or less | −26.148* (10.573) |

5.710 (19.434) |

−12.909 (10.673) |

29.830 (20.228) |

| Secondary | −18.886** (6.798) |

−16.740 (12.495) |

−10.775 (6.862) |

27.542* (13.005) |

|

| Age of the mother (ref=35-49) | 20-34 | 2.130 (6.268) |

1.827 (11.522) |

9.597 (6.328) |

−7.015 (11.992) |

| Age of the youngest child (ref=4-9) | 0-3 | −20.174*** (6.030) |

51.801*** (11.084) |

0.297 (6.087) |

75.099*** (11.537) |

| Day of the week (ref=weekend) | Weekday | −6.055 (6.330) |

−218.659*** (11.635) |

−12.746* (6.390) |

101.743*** (12.111) |

| Domestic service (ref=No) | Yes | 4.886 (9.188) |

−32.417+ (16.888) |

9.894 (9.275) |

26.556 (17.578) |

| Constant | 118.162*** (9.280) |

390.609*** (17.057) |

38.912*** (9.368) |

187.396*** (17.754) |

|

| Observations | 1,177 | 1,177 | 1,177 | 1,177 | |

| R-squared | 0.022 | 0.261 | 0.084 | 0.190 |

Standard errors in parentheses

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Source: Own calculations from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. INE

Table 1.

Sample description. Proportion of couples according to the main characteristics

| Variable | Category | Dual-earner and Male- breadwinner couples |

Dual-earner couples | Male breadwinner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

| Type of couple | Dual-earner | 63.3 | ||

| Male-breadwinner | 36.4 | |||

| Type of union | Cohabiter | 8.7 | 10.3 | 5.8 |

| Married | 91.3 | 89.7 | 94.2 | |

| Educational attainment of the mother |

Primary or less | 9.9 | 7.2 | 14.5 |

| Secondary | 56.5 | 50.1 | 67.8 | |

| University | 33.6 | 42.7 | 17.7 | |

| Age of the mother | 20-34 | 35.7 | 33.0 | 40.4 |

| 35-49 | 64.3 | 67.0 | 59.6 | |

| Age of the youngest child in the household |

3 or less | 52.1 | 50.6 | 54.7 |

| 4-9 | 47.9 | 49.4 | 45.3 | |

| Day of the week | Weekday | 61.0 | 63.3 | 57 |

| Weekend | 39.0 | 36.7 | 43 | |

| n | 1177 | 749 | 428 | |

Source: Own calculations from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. INE

A similar situation is observed during weekends, where mothers spend less time with their children (approximately 1:42) and fathers spend slightly more time with their children (approximately 13 minutes) than during weekdays. However, the most important characteristic of family time during weekends is the increase in parent time. During weekends, work constraints are lower, and parents are able to spend more time with their spouses and children together.

Mother time differences are also significant when children are younger. The co-presence of children under 3 years old in the household increases mother time by 1 hour and 15 minutes. The greater attention required by younger children is also reflected in an increase of 52 minutes of parent time, but it is not observed for father time. The presence of children younger than 3 years also reduces the time alone with the spouse. These results confirm that mothers remain the main responsible parent in childcare, and this is more evident for young children, who require more attention.

After presenting the main differences in family time between MB and DE couples, we now focus on DE couples to explore the gender differences in parenting when both parents are working. Other things being equal, we know that fathers spend less time with their children; we are interested in understanding if the determinants of parenting time differ for mothers and fathers. Table 5 presents the estimates of being with children without the spouse for fathers and mothers of dual-earner couples. The coefficients correspond to the odds ratio of being alone with children in a concrete 10-minute interval of time when a considered family activity is performed. The father time column corresponds to the odds of fathers being alone with their children, and mother time corresponds to the odds of mothers being alone with their children.

Table 5.

Logistic regression father and mother. Odds ratio for fathers and mothers of being alone with children. Dual-earner couples with children

| Father time | Mother time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Union status (ref=married) | Cohabiter | 1.4*** (0.080) |

1.1** (0.052) |

| Eduational attainment of the mother (ref=University) |

Primary or less | 0.6*** (0.049) |

0.7*** (0.044) |

| Secondary | 0.8*** (0.034) |

1.0 (0.031) |

|

| Age of the mother (ref=35-49) | 20-34 | 1.0 (0.044) |

1.0 (0.033) |

| Age of the youngest child (ref=4-9) | 0-3 | 1.1 (0.044) |

1.1*** (0.035) |

| Day of the week (ref=weekend) | Weekday | 1.1 (0.044) |

1.2*** (0.036) |

| Time of the day (ref=afternoon/evening) | Morning | 1.3*** (0.053) |

0.9* (0.029) |

| Domestic service (ref=No) | Yes | 1.3*** (0.062) |

1.2*** (0.046) |

| Partner at work (ref=No) | Yes | 8.5*** (0.412) |

5.8*** (0.193) |

| Constant | 0.1*** (0.005) |

0.2*** (0.007) |

|

| Observations | 36,117 | 42,637 |

Standard errors in parentheses

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Source: Own calculations from the Spanish Time Use Survey 2009-2010. INE

For both fathers and mothers, the estimates show that the probability is higher when their partners are at work. However, this risk is greater for fathers (8.5 times) than for mothers (5.7 times). Therefore, father time seems to be more affected by the work schedules of mothers. Fathers are more involved with their children when their presence is required more, in this case, when their partners are working.

The results by day of the week and the age of the youngest child also present gender differences. During weekdays, mothers are more involved with their children, and they are more likely to be alone with them. The results for fathers are not significant, which means that behavior on weekends and weekdays does not change. This situation is a clear sign that mothers are more involved even when work constraints are more relevant, whereas fathers are less affected. Mothers spend more time alone with their children when their children are younger and require more attention, and this is also an indicator of the greater responsibility of mothers for childcare.

The time of day when the activity is performed has a different effect for fathers and mothers. Fathers being alone with their children present a greater probability in the morning, whereas a higher probability of mothers being alone with their children is observed in the afternoon/evening.

Conclusions

Family time is important to families. Family time is a sign of well-being because people wish to spend time with their spouses and children. However, the constraints of family organization make it more difficult to spend time with a spouse and children. In this paper, we explored the differences in family time between the two main models of the family: male-breadwinner couples, where only the father works, which is considered more traditional concerning the allocation of time, and dual-earner couples, where both members of the couple work, which reflects more equality regarding the division of time. In Spain, we have found similarities between both types of couples, but some characteristics differ.

Meals and leisure are the main activities shared with the spouse and children together. Primary care and media are also important. Media is definitely the most important activity shared only with the spouse. The main activity of both mothers and fathers who are alone with their children is primary childcare. For mothers, unpaid work is also an important activity performed in the presence of children.

However, although the activities are similar, the amount of time spent on each activity differs considerably, and as a result, dual-earner couples spend much less time with their families than male-breadwinner couples (H1). The differences are concentrated on weekdays, when the constraints of the work schedule are more evident. Consequently, when couples have more free time and do not have to address job limitations, many differences disappear, and couples spend family time similarly despite the type of couple (H1b).

We also found smaller differences in the time spent with the spouse for different types of couples depending on the day of the week. This result reinforces the idea from previous studies that clear trends in the time spent with a spouse were not identified. There is no clear difference in spousal time between male-breadwinner and dual-earner couples as there is in time with children (H1a). Dual-earner couples are typically less traditional, which leads to increasingly separate lifestyles for males and females. Dual-earner couples must also organize two different work schedules, and this reduces the time spent with their partners. Nevertheless, a decrease in the time with a spouse is not reflected in couples in which both members are employed. This result means that couples want to spend time together, and they try to coordinate their schedules and avoid the constraints of work to have more time for one another.

Gender differences in parenting have shortened, but they are still considerable in the Spanish context. The major differences are found in the time spent by mothers and fathers alone with their children. Our hypothesis suggested that gender differences would prevail (H2). Mothers’ time alone with their children is always greater than fathers’ time alone with their children, which means that mothers still have the main responsibility of caring for the children in the household. These differences are significant especially when we compare the characteristics of a couple with equality in the relationship (specifically breadwinner couples during weekdays). Mothers are almost the only providers of care if we consider the substantial amount of time they spend with their children compared with the small amount of time that fathers spend. More egalitarian characteristics reduce these differences, but considerable differences persist (H2a). There is more gender equality in dual-earner couples, but complete equality is far from existent. It is also important to consider how mothers deal with their roles in their careers because sometimes, their only solution is multitasking, simultaneously performing other activities when caring for their children (H2b). This fact is reflected in the significant amount of time that mothers spend performing unpaid work in the presence of their children. This situation can lead to time pressures and negative consequences for the well-being of mothers when they face the double dilemma of not only participating in the labor market but also taking care of the household. The presence of younger children (in our case, three years old or less) who need more attention also supposes an important increase in mothers’ time with their children. This effect is not observed in fathers’ time with their children. In this case, traditional norms that assign to the mother the role of main caregiver persist, and this behavior remains very strong in Spain, as previous studies have suggested (Sevilla Sanz et al. 2010, Gimenez Nadal and Sevilla, 2014). Spanish society is moving slowly towards a more egalitarian organization and the scarcity of policies for balancing work and family makes it more complicated. We also have to consider that balancing the role of caregiver and breadwinner may have a negative effect on mothers’ career that still maintain family responsibilities as a priority.

The total amount of fathers’ time with their children has increased and reflects the idea of a more active fatherhood. New fathers want to be more involved in their children’s development, and they want to spend more time together. We have also observed that in the increase in fathers’ time with their children, there is also a component of obligation to balance the participation of mothers in the labor market (H2c).

We must consider that the measure of family time based on the presence of family members may pose some problems evaluating the actual interaction between them. It is interesting to note that it is very difficult or nigh on impossible to find any data about actual interaction and the measure according to the presence of family members has been widely used since the 1980s (Kingston and Nock 1984; Lesnard 2008; Gutierrez Domenech 2010). Another important issue to take into account about our findings is the context of economic crises when the survey was carried out. Specific and transitory circumstances may lead to temporary arrangements in the families that will not persist in the future.

Nevertheless, the higher participation of fathers in caring for their children in dual-earner couples is insufficient to offset the decrease in mothers’ time in dual -earner couples. As a result, children spend less time with some of their parents during the day. It is difficult to predict the consequences of this lack of parental time with children, especially for the youngest children, but it is clear that it will have consequences for on subsequent child development (Pleck 2010).

From a practical point of view, it also begs the question of how families can arrange their schedules. In the case of Spain, the support of the extended family has always been an important factor for helping to the balance between work and family. In this sense, the presence of grandparents and other close relatives is fundamental and it is the main arrangement that facilitates the participation of mothers and fathers in the labour market (Baizan et al. 2013). The possibility of external help (parental leave, kindergarten, money transfers) can be problematic but is the only solution in most cases when public support is scarce (Esping-Andersen et al. 2013; Lapuerta et al. 2011).

Family arrangements have become more complicated in this context in which parents are challenged by the need of balancing work and family and accommodating the desire to spend time with spouse and children. While recent opinion surveys reflect a changing attitude of the Spanish society towards more egalitarian views on allocation and the division of roles (CES, 2011), traditional behaviors in caregiving activities are relatively persistent. There is a long way to go to address this gap between attitudes and behaviors in family time and gender arrangements.

Footnotes

We group full-time and part-time employed people. In Spain, the proportion of part-time workers is low, and this distinction would not add much to our analysis. (In 2010, the incidence of part-time employment in Spain was 12.4% (OECD, 2012).)

Contributor Information

Joan Garcia Roman, jgarciar@umn.edu Minnesota Population Center.

Clara Cortina, clara.cortina@upf.edu Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

References

- Abril P, Amigot R, Botia-Morillas C, Dominguez-Folgueras M, Gonzalez MJ, Jurado-Guerrero T, Lapuerta I, Martin-Garcia T, Monferrer J, Seiz M. Egalitarian ideals and traditional plans: Analysis of first time parents in Spain. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociologicas. 2015;150:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ajenjo M, Garcia-Roman J. Cambios en el uso del tiempo de las parejas. Estamos en el camino hacia una mayor igualdad? Revista Internacional de Sociologia. 2014;72(2):453–476. [Google Scholar]

- Ajenjo M, Garcia-Roman J. El tiempo productivo, reproductivo y de ocio en las parejas de doble ingreso. Papers. Revista de Sociologia. 2011;96(3):985–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi I. La nueva familia española. Grupo Santillana de Ediciones, S.A; Madrid: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Batalova JA, Cohen PN. Pre-marital cohabitation and housework, couples in cross national perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:743–755. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter J. To marry or not to marry, marital status and the household division of household. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26(3):300–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard J. The future of marriage. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Baizan P, Domínguez M, González MJ. Couples bargaining or socio-economic status. European Societies. 2014;16(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barnet-Verzat C, Pailhe A, Solaz A. Spending time together, the impact of children on couples’ leisure synchronization. Review of Economics of the Household. 2011;9:465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA, Sayer L, Robinson J. Is anyone doing the housework, trends in the gender division of household labour. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. Changing the Rhythms of American Family Life. Russell Sage Foundation; Nueva York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bittman M, Wajcman J. The rush hour, character of leisure time and gender equity. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemen H, Stancanelli E. Market hours, household work, child care, and wage rates of partners: an empirical analysis. Review of Economics of the Household. 2014;12:51–81. [Google Scholar]

- CES . Tercer informe sobre la situación sociolaboral de las mujeres en España. Consejo Económico y Social; Madrid: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Research on Household Labour, Modeling and Measuring the Social Embeddedness of Routine Family Work. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(4):1208–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Mullan K. How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross national time-use comparison. American Sociological Review. 2001;76(6):834–861. [Google Scholar]

- Daly KJ. Deconstructing family time, from ideology to lived experience. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;58(1):283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dema S. Entre la tradición y la modernidad, las parejas españolas de doble ingreso. Papers. 2005;77:135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dew G. Has the marital time cost of parenting changed over time? Social Forces. 2009;88(2):519–541. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Folgueras M. Parenthood and domestic división of labour in Spain, 2002-2010. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociologicas. 2015;149:45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Folgueras M, Castro-Martin T. Women’s changing socioeconomic position and union formation in Spain and Portugal. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1513–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. The incomplete revolution. Polity press; Cambridge: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Esping Andersen G, Boertien D, Bonke J, Gracia P. Couple Specialization in multiple equilibria. European Sociological Review. 2013;29:1280–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Flood S, Genadek K. Time For each other: Work and family constraints among couples. MPC Working Papers Series. 2013:2013–14. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT, Sanchez L. Two as one? Couples’ perceptions of time spent together, marital quality, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Roman J. El tiempo con la familia en las parejas de doble ingreso. Un análisis a partir de la Encuesta de Empleo del Tiempo 2009-2010. Estadística Española. 2013;55(182):259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gershuny J. Changing times, work and leisure in postindustrial society. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gestel N, Sarkisian Marriage, The good, the bad, and the greedy. Contexts. 2006;5(4):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Nadal JI, Sevilla A. Total work time in Spain: evidence from time diary data. Applied Economics. 2014 Feb;46(16):1894–1909. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Nadal JI, Molina JA. Parents’ education as a determinant of educational childcare time. Journal of Population Economics. 2013;26:719–749. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Nadal JI, Molina JA, Sevilla-Sanz A. Social norms, partnerships and children. Review of Economics of the Household. 2012;10:215–236. [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux I, Minnen J, Pieter van Tienoven T. Spouse together time, quality time within the household. Social Indicators Research. 2010;101:281–287. [Google Scholar]

- González MJ, Jurado Guerrero T. ¿Cuándo se implican los hombres en las tareas domésticas? Un análisis de la Encuesta de Empleo del Tiempo. Panorama Social. 2009;10:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez MJ, Dominguez M, Luppi F. Men anticipating fatherhood in Spain. In: Esping-Andersen G, editor. The fertility gap in Europe, Singularities of the Spanish case. Vol. 36. Social Studies Collection; 2013. pp. 136–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia P, Kalmijn M. Parents’ family time and work schedules: The split-shift schedule in Spain. Journal of Marriage and Family. (forthcoming) [Google Scholar]

- Gracia P. Fathers child care involvement and children’s age in Spain, A time use study on differences by education and mothers’ employment. European Scoiological Review. 2014:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia P, Bellani D. Las políticas de conciliación y sus efectos en España: Un análisis de la desigualdad de género en el trabajo del hogar y el empleo. Alternativas-Estudios de Progreso. 2010:51. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Domènech M. Parental Employment and Time with Children in Spain. Review of Economics of the household. 2010;8(3):371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg D, Klevmarken A. Time for Children, A Study of Parent’s Time Allocation. Journal of Population Economics. 2003;16:205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hammermesh D. Timing togetherness and time windfalls. Journal of Population Economics. 2002;15(4):601–623. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR. The time bind, when work becomes home and home becomes work. Metropolitan Books; Nueva York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Encuesta de Empleo del Tiempo 2009-2010. Metodología. 2011 http,//www.ine.es/metodologia/t25/t25304471.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, Bernasco W. Joint and separated lifestyles in couple relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(3):639–654. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston PW, Nock SL. Time together among dual-earner couples. American Sociological Review. 1987;52(3):391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lapuerta I, Baizan P, Gonzalez MJ. Individual and Institutional constraints, an analysis of parental leave use and duration in Spain. Population Research Policy Review. 2011;30:185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lesnard L. Off-Scheduling within Dual-Earner Couples, An Unequal and Negative Externality for Family Time. American Journal of Sociology. 2008;114(2):447–490. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. Work Family balance, gender and policy. Edgar Elgar Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meil G. El reparto desigual del trabajo doméstico y sus efectos sobre la estabilidad de los proyectos conyugales. Revista Espanola Investigaciones Sociologicas. 2005;111:163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Offer S, Schneider B. Revisting the gender gap in time use patterns, Multitasking and wellbeing among mothers and fathers in dual-earner families. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(6):809–833. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck J. Paternal involvement, revised conceptualization and theoretical linkages with child out-comes. In: Lamb M, editor. The roles of Father in child development. John Willey; New York: 2010. pp. 58–93. [Google Scholar]

- Presser HB. Shift work and child care among young dual-earner American parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1988;50(1):133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Presser HB. Working in a 24/7 Economy, Challenges for American families. Russel Sage Foundation; Nueva York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Godbey G. Time for Life-The Surprising Ways People Use Their Time. Penn States Press; University Park: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh S. I wish we had more time spend together⋯, The distribution and predictors of perceived family time pressure among married men and women in the paid labor force. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:529–552. [Google Scholar]

- Roeters A, Cloin M, Van Der Lippe T. Solitary time and mental health in the Netherlands. Social Indicators Research. 2013 Doi 10.1007/s11205-013-0523-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer LC. Gender, time and inequality, Trends in women's and men's paid work, unpaid work and free time. Social Forces. 2005;84(1):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla A. On the importance of time diary data and introduction to a special issue on time use research. Review of Economics of the Hosuehold. 2014;12:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla-Sanz A, Giménez-Nadal JI, Fernández C. Gender roles and the division of unpaid work in Spanish Households. Feminist Economics. 2010;14(4):137–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan O. Time co-ordination, the domestic division of labour and affective relations, Time use and the enjoyment of activities within couples. Sociology. 1996;30(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. What children need. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wight V, Raley S, Bianchi S. Time for children, one’s spouse and oneself among parents who work nonstandard hours. Social Forces. 2008;87(1):243–271. [Google Scholar]

- Voorspostel M, Van der Lippe T, Gershuny J. Trends in free time with a partner, A transformation of intimacy? Social Indicators Research. 2009;93:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9383-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C, Zimmermann DH. Doing Gender. Gender & Society. 1987;1:125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zick CD, Bryant WK, Osterbacka E. Mothers’ employment, parental involvement, and the implications for intermediate child outcomes. Social Science Research. 2001;30:25–49. [Google Scholar]