Abstract

Objective

To report 2‐year patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) from the head‐to‐head Abatacept versus Adalimumab Comparison in Biologic‐Naive RA Subjects with Background Methotrexate (MTX) (AMPLE) trial.

Methods

AMPLE was a phase IIIb, randomized, investigator‐blinded trial. Biologic‐naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and an inadequate response to MTX were randomized to subcutaneous (SC) abatacept (125 mg/week) or adalimumab (40 mg every 2 weeks) with background MTX. PROs (pain, fatigue, ability to perform work, and ability to perform daily activities) were compared up to year 2 for patients in each treatment group, as well as those who achieved low disease activity at both years 1 and 2 (responders) and those who did not (nonresponders).

Results

A total of 646 patients were randomized and treated with SC abatacept (n = 318) or adalimumab (n = 328). Baseline characteristics were balanced between the 2 treatment arms. Comparable improvements in PROs were observed in the abatacept and adalimumab groups over 2 years, with both groups achieving clinically meaningful improvements in PROs from baseline. At year 2, fatigue improved by 23.4 mm and 21.5 mm on a 100‐mm visual analog scale with abatacept and adalimumab, respectively. Clinical responders achieved greater improvements in PROs than nonresponders.

Conclusion

In biologic‐naive patients with active RA, despite prior MTX, treatment with SC abatacept or adalimumab with background MTX resulted in comparable improvements in PROs, which were highly correlated with physician‐reported clinical response end points.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) can have a major impact on patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) that evaluate health, quality of life, and treatment response from the perspective of the patient. PROs that are considered to have a particularly large impact on the quality of life of patients with RA include pain, fatigue, the ability to perform work, and the ability to perform daily activities 1.

Box 1. Significance & Innovations.

In biologic‐naive patients with active rheumatoid arthritis, despite prior methotrexate (MTX), treatment with subcutaneous abatacept or adalimumab with background MTX resulted in comparable improvements in patient‐reported outcomes (PROs), such as pain, fatigue, ability to perform work, and ability to perform daily activities.

Improvements in these PROs were highly correlated with physician‐reported clinical response end points, including low disease activity or remission, as assessed by Simplified Disease Activity Index, Clinical Disease Activity Index, or Boolean criteria.

The treat‐to‐target strategies employed in RA aim to achieve significant improvements in clinical outcomes, with the goal of remission, or if remission cannot be achieved, low disease activity. However, whether achievement of these goals is associated with meaningful improvements in PROs remains unclear. It is, therefore, important that PROs are evaluated in conjunction with clinical outcomes, particularly when disease activity is assessed using a measure that does not include a patient‐reported component. As both clinical outcomes and PROs are important, their interrelationship should be investigated.

Both the current American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommendations and the European League Against Rheumatism guidelines recommend methotrexate (MTX) as first‐line therapy for RA, with the addition of biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients who experience an inadequate response to MTX 2, 3. Abatacept is a T‐cell costimulation modulator that has shown efficacy in patients with RA in a wide range of disease and treatment durations 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. The AMPLE (Abatacept versus Adalimumab Comparison in Biologic‐Naive RA Subjects with Background MTX) trial, the first head‐to‐head trial comparing biologic DMARDs in patients with RA receiving MTX, demonstrated noninferiority for abatacept versus adalimumab by the ACR 20% improvement response (ACR20) at year 1 (64.8% subcutaneous [SC] abatacept versus 63.4% adalimumab; estimated difference between treatments 1.8% [95% confidence interval (95% CI) −5.6, 9.2] in an intent‐to‐treat analysis) 12. In AMPLE, there was a similar time of onset of ACR20 response in both treatment groups, with the response maintained up to year 2 13.

AMPLE included a diverse range of PRO analyses and is the first biologic DMARD head‐to‐head evaluation of PROs in RA. Comparable improvements from baseline to year 1 were seen in fatigue with SC abatacept and adalimumab (−23.2% SC abatacept versus −21.4% adalimumab; adjusted treatment difference −1.8% [95% CI −5.8, 2.2]) 12. Results for pain over 1 and 2 years have also been presented previously 14. Here, 2‐year results from the AMPLE trial are reported, directly comparing the effects of abatacept and adalimumab on the PROs of pain, fatigue, the ability to perform work, and the ability to perform daily activities, as well as the relationship between these 4 PROs and clinical outcomes.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The AMPLE study design and patient inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described previously 13. Briefly, patients had active RA for ≤5 years, as defined by the 1987 ACR criteria for RA 15, had reported an inadequate response to MTX, were biologics‐naive, and had a Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C‐reactive protein (DAS28‐CRP) level ≥3.2. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to either SC abatacept (125 mg/week) or adalimumab (40 mg every 2 weeks), in addition to a stable dose of MTX (15–25 mg/week).

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki; with Good Clinical Practice, as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization; with the ethical principles underlying European Union Directive 2001/20/EC; and with the US Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 50 (21CFR50). The laws and regulatory requirements of all countries participating in this study were followed.

PRO assessments

PROs deemed important to patients with RA and assessed in AMPLE were pain, fatigue, ability to perform work, and ability to perform daily activities. All except pain were evaluated on day 1, month 6, year 1, and year 2.

Pain and fatigue

Pain was measured using a 100‐mm visual analog scale (VAS), with a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) defined as a change of −10 mm from baseline 14, 16. Pain was evaluated at days 1, 15, and 29, and every 4 weeks thereafter during year 1, and every 3 months during year 2. Patients’ assessment of the severity of fatigue over the past week was measured using a 100‐mm VAS. An MCID was defined as a change of −10 mm from baseline 17.

Ability to perform work

Four components of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Rheumatoid Arthritis (WPAI:RA) were analyzed, including absenteeism (work time missed), presenteeism (impairment at work/reduced on‐the‐job effectiveness), work productivity loss (overall work impairment/absenteeism plus presenteeism), and activity impairment. For baseline values these components are reported as work time missed, impairment at work, overall work impairment, and activity impairment. For posttreatment values they are reported as work time gained, reduced impairment while working, overall reduced work impairment, and activity gained. An MCID for WPAI:RA was defined as a 7% absolute change in WPAI:RA score 18.

Ability to perform daily activities

The Activity Limitation Questionnaire was used to assess the number of days in the past 30 days that a patient was unable (baseline values) or able (posttreatment values) to perform usual activities owing to RA. An MCID was defined as a change of 4 days from baseline (i.e., patients able to perform daily activities on 4 additional days) 17.

Post hoc analyses: PROs in clinical responders versus nonresponders

Post hoc analyses were performed to determine the proportions of patients who achieved clinical response scores according to the following criteria: ACR20 response, Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) low disease activity (<10) and remission (<2.8), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) low disease activity (<11) and remission (<3.3), and Boolean remission (<1). The 4 PROs (pain, fatigue, ability to perform work, and ability to perform daily activities) were compared for patients with clinical responses (responders, as defined above) and those without (nonresponders) at month 6, year 1, and year 2.

Statistical analysis

All efficacy analyses were performed on the intent‐to‐treat population, which included all patients who were randomized and received ≥1 dose of study drug. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were analyzed descriptively. For fatigue and ability to perform daily activities, changes from baseline were summarized by treatment and visit, and 95% CIs for the treatment differences were constructed. For ability to perform work, percentage reduction from baseline in each of the 4 components of impairment was reported by treatment and visit. Between–treatment group differences in impairment reduction were also assessed using the point estimation and 95% CI. Definitions of MCIDs for individual outcomes are given above. For all patients who completed day 729 (year 2), individual responses/nonresponses for ACR20 response and remission/low disease activity (CDAI, SDAI, and Boolean) were calculated using post hoc analyses of as‐observed data (i.e., all data available). All patients who prematurely discontinued the study after receiving study drug, regardless of reason, were considered nonresponders at all subsequent visits for the clinical response measures. For all PROs, adjusted mean changes from baseline were summarized by treatment group and were based on an analysis of covariance model, with treatment as the main factor and baseline values with DAS28‐CRP stratification as covariates.

RESULTS

A total of 646 patients were randomized and treated, 318 patients in the SC abatacept group and 328 patients in the adalimumab group. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics, including PRO measures, were well balanced between the 2 treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, 79.2% of patients treated with SC abatacept and 74.7% of patients treated with adalimumab completed the 2‐year study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and patient‐reported outcomesa

| Demographics and PROs | SC abatacept + MTX (n = 318) | Adalimumab + MTX (n = 328) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 51.4 ± 12.6 | 51.0 ± 12.8 |

| Women, % | 81.4 | 82.3 |

| White, % | 80.8 | 78.0 |

| Disease duration, years | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 1.4 |

| HAQ DI score | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| DAS28‐CRP score | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 1.1 |

| Pain scoreb | 63.1 ± 22.3 | 65.5 ± 21.8 |

| Fatigue scoreb | 60.6 ± 25.0 | 60.1 ± 25.4 |

| Ability to perform work scorec | ||

| Percentage work time missed | 10.9 ± 21.5 | 13.5 ± 25.1 |

| Percentage impairment at work | 47.2 ± 28.5 | 51.4 ± 27.7 |

| Percentage overall work impairment | 50.2 ± 29.5 | 54.4 ± 29.6 |

| Percentage activity impairment | 56.3 ± 24.6 | 57.1 ± 25.9 |

| Ability to perform daily activities score, daysd | 11.7 ± 10.4 | 12.4 ± 10.3 |

Values are mean ± SD unless indicated otherwise. Baseline fatigue, ability to perform work, and ability to perform daily activities scores presented for patients with available data at 2 years (abatacept and adalimumab, respectively: fatigue, n = 310 and n = 315; work time missed, n = 137 and n = 130; impairment at work, overall work impairment, and activity impairment, n = 134 and n = 126; ability to perform daily activities, n = 308 and n = 310). SC = subcutaneous; MTX = methotrexate; HAQ DI = Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index; DAS28‐CRP = Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C‐reactive protein level.

Pain and fatigue measured on a visual analog scale with 100‐mm score.

Ability to perform work assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Ability to perform daily activities assessed as the number of days that patients were unable to perform normal activities during the past 30 days using the Activity Limitation Questionnaire.

Change in PROs during the study period

Pain

Over the 2‐year study period, comparable improvements were seen in the SC abatacept and adalimumab treatment groups for most of the 4 PROs assessed. Numerically greater improvements in pain were observed for patients who received abatacept versus adalimumab over 2 years 14. Mean ± SEM improvements in pain at year 2 for abatacept versus adalimumab were 53.7% ± 6.2% versus 38.5% ±6.1%, respectively, with an adjusted mean treatment difference of 15.2% (95% CI −1.2, 31.6) (published previously) 14. An MCID in pain was reached from day 15 for both treatment groups.

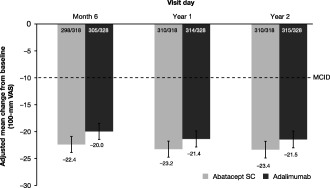

Fatigue

Comparable improvements in fatigue were observed in the abatacept and adalimumab treatment groups over 2 years (Figure 1). Adjusted mean change in fatigue reached an MCID (−10 mm) as early as day 15 in both treatment groups, with improvements being maintained up to year 2.

Figure 1.

Mean improvements in patient fatigue over 2 years, in an intent‐to‐treat population. All patients with baseline and postbaseline measurements were used for this analysis. Error bars represent SEM. VAS = visual analog scale; MCID = minimum clinically important difference; SC = subcutaneous.

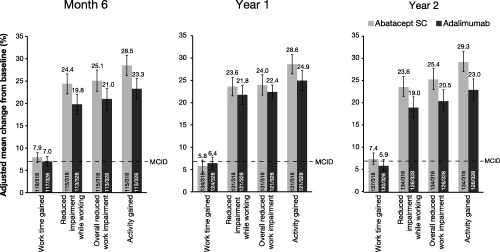

Ability to perform work

The 4 components of the WPAI:RA were found to be similarly improved in patients receiving abatacept and those receiving adalimumab over the 2‐year study (Figure 2). In both the abatacept and the adalimumab treatment groups, improvements in the components of reduced impairment while working, overall reduced work impairment, and activity gained reached an MCID (7%) at all postbaseline assessments (month 6, year 1, and year 2).

Figure 2.

Mean improvements in patient ability to perform work, over 2 years, as assessed by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Rheumatoid Arthritis, in an intent‐to‐treat population. All patients with baseline and postbaseline measurements were used for this analysis. Error bars represent SEM. SC = subcutaneous; MCID = minimum clinically important difference.

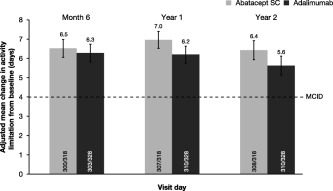

Ability to perform daily activities

As seen for the ability to perform work assessments, improvements in patients’ ability to perform daily activities over 2 years were similar in both the abatacept and the adalimumab treatment groups (Figure 3). Again, the MCID for ability to perform daily activities of 4 additional days was seen in both treatment groups at all postbaseline assessments (month 6, year 1, and year 2).

Figure 3.

Mean improvements in patients’ activity limitation, over 2 years, as number of days that patients are able to perform normal activities during the past 30 days, assessed by the Activity Limitation Questionnaire in an intent‐to‐treat population. All patients with baseline and postbaseline measurements were used for this analysis. Error bars represent SEM. SC = subcutaneous; MCID = minimum clinically important difference.

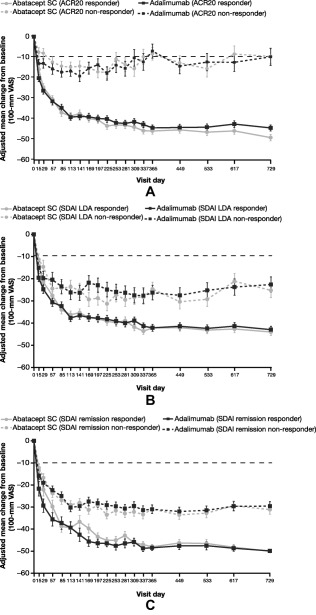

PROs in clinical responders versus nonresponders

The results of the post hoc analyses showed that, for each of the 4 PROs evaluated, there was clear separation between patients who achieved clinical response (responders) and those who did not (nonresponders), regardless of whether they received abatacept or adalimumab. This separation was true for each of the 6 clinical outcomes assessed, except when using Boolean remission to assess the ability to perform daily activities in clinical responders versus nonresponders. As pain was assessed more frequently than the other PROs, which were assessed at month 6, year 1, and year 2, the association of pain improvement with clinical response is shown in Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 1 (available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22763/abstract) as a representative example. Adjusted mean improvements in pain reached an MCID as early as day 15 in both responder and nonresponder groups for all low disease activity and remission criteria; these improvements were maintained up to year 2 (see Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 1). For each PRO and each clinical measure, the number of patients was similar in the 2 treatment groups, for both responder and nonresponder subgroups. Abatacept and adalimumab responders had similar improvements in each PRO over time.

Figure 4.

Improvements in patient pain over 2 years in responder and nonresponder patient subgroups, in an intent‐to‐treat population, defined by clinical response criteria: (A) American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement (ACR20) response, (B) Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) low disease activity (LDA), and (C) SDAI remission. All patients with baseline and postbaseline measurements were used for this analysis. Error bars represent SEM. SC = subcutaneous; VAS = visual analog scale.

DISCUSSION

Over 2 years of the AMPLE trial, patients treated with SC abatacept or adalimumab while receiving background MTX achieved comparable, clinically meaningful improvements with a similar onset of response in 4 PROs: pain 14, fatigue, ability to perform work, and ability to perform daily activities. Furthermore, post hoc analysis of the 4 PROs showed a clear association between clinical response according to several clinical criteria (ACR20 response, CDAI low disease activity, CDAI remission, SDAI low disease activity, SDAI remission, and Boolean remission) and improvement in PROs, with the exception of an association between Boolean remission and the ability to perform daily activities.

PROs capture the effects of treatment from a patient's perspective and are critical to ensuring that a clinical response corresponds to benefits that are perceptible and important to the patient 19. Patients and clinicians want RA treatments that rapidly improve health‐related quality of life and reduce or halt functional impairment, with improvements maintained over time 20. Pain and loss of physical function are meaningful outcomes that need to be considered by clinicians as important consequences of RA 21; patients also identify fatigue as having a considerable influence on quality of life 22, 23.

The results reported here are consistent with data from other published studies of the effect of abatacept on PROs, including ATTEST (Abatacept or Infliximab Versus Placebo: A Trial for Tolerability, Efficacy, and Safety in Treating RA), AIM (Abatacept in Inadequate Responders to MTX), and ACQUIRE (Abatacept Comparison of SC Versus Intravenous in Inadequate Responders to MTX). As in AMPLE, these 3 abatacept studies included patients with an inadequate response to MTX who were biologics‐naive 5, 24, 25, 26.

The results presented here are also consistent with published PRO data for adalimumab 27, 28, 29. In the Anti‐TNF Research Study Program of the Monoclonal Antibody Adalimumab trial, patients who had an inadequate response to MTX and were treated with adalimumab plus MTX demonstrated significant improvements in physical function from baseline to year 4 (mean Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index [HAQ DI] 0.7 and 1.5, respectively [P < 0.001]) 27. Similarly, in the DE019 adalimumab study, patients who had an inadequate response to MTX who received up to 10 years of adalimumab plus MTX therapy demonstrated a reduction in mean HAQ DI from 1.4 at baseline to 0.7 at year 10, while 42% of patients achieved HAQ DI <0.5 (normal functionality) at year 10 28. In the PREMIER study, significant improvements from baseline to year 2 in HAQ DI (P < 0.0001), Short Form 36 health survey physical component summary score (P < 0.0001), patient global assessment score (P < 0.0001), and pain score (P < 0.0001) were reported by patients with early RA treated with adalimumab plus MTX versus patients treated with MTX monotherapy 29.

The goal of current treat‐to‐target strategies in patients with RA is the achievement of remission, but with the recognition that low disease activity may be an acceptable alternative if remission is not achievable, particularly for those with advanced established disease 30. By correlating clinical response with PROs that are important to both physicians and patients, such as pain, fatigue, work productivity, and activity impairment, the achievement of how a good clinical response translates into meaningful benefits for the patient in their daily life can be better understood. Greater reductions in the signs and symptoms of RA (ACR20 response) and disease activity (low disease activity or remission, as assessed by SDAI, CDAI, or Boolean criteria) were associated with greater improvements over 2 years in the 4 PROs assessed (except for ability to perform daily activities when assessed by Boolean remission), with comparable benefits observed with SC abatacept and adalimumab.

Concerning the effect of RA on the ability to maintain employment, previous studies have found greater disease activity to be significantly correlated with higher numbers of missed work hours (absenteeism), greater work impairment (presenteeism), and greater activity impairment 31, 32. How relatively small changes in disease activity, such as from low disease activity to remission, can impact PROs is unclear. Nonetheless, reaching an MCID in pain, fatigue, or physical function can result in significantly greater improvements in work productivity compared with patients who did not achieve MCID in these outcomes 33. Furthermore, a recent study reported worse work productivity in patients achieving low disease activity than in those achieving disease remission 34.

Limitations to this analysis should be considered. Although the AMPLE trial was powered to compare abatacept and adalimumab directly, it was a single‐blind design, rather than double‐blind, which may have introduced bias 14. An additional limitation was the post hoc nature of the analyses that compared PROs in patient subgroups based on clinical response.

In summary, this study demonstrated that in patients with RA who were biologics‐naive, treatment with SC abatacept or adalimumab is associated with comparable improvements in PROs that are considered particularly important in RA (pain, fatigue, work productivity, and activity limitation). Furthermore, improved PROs were associated with physician‐reported clinical responses.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Dr. Fleischmann had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Fleischmann, Weinblatt, Schiff, Khanna, Maldonado, Nadkarni, Furst.

Acquisition of data

Fleischmann, Furst.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Fleischmann, Weinblatt, Schiff, Khanna, Nadkarni, Furst.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSOR

Bristol‐Myers Squibb facilitated the study design and reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to submission. The authors had full access to the study data, contributed to the interpretation of the results, and had ultimate control over the decision to publish and the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1. Improvements in patient pain over 2 years in responder and non‐responder patient subgroups, defined by clinical response criteria: (A) CDAI LDA, (B) CDAI remission, and (C) Boolean remission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Professional medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Carolyn Tubby, PhD (Caudex), and funded by Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00929864.

Supported by Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

Dr. Fleischmann has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi‐Aventis, and UCB (more than $10,000 each), and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi‐Aventis, and UCB (less than $10,000 each).

Dr. Weinblatt has received research grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, and UCB (less than $10,000 each), and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, Janssen, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB (less than $10,000 each) and from Eli Lilly (more than $10,000).

Dr. Schiff has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Antares, Eli Lilly, Horizon, Johnson & Johnson, Roche, and UCB (less than $10,000 each) and from Bristol‐Myers Squibb (more than $10,000), and has received speaking fees from AbbVie (more than $10,000).

Dr. Khanna has received honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb (more than $10,000). Drs. Maldonado and Nadkarni own stock or stock options in Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

Dr. Furst has received research grants from AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, and UCB (less than $10,000 each), and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, and UCB (less than $10,000 each), and has received speaking fees from AbbVie, Actelion, and UCB (less than $10,000 each).

REFERENCES

- 1. Wells AF, Jodat N, Schiff M. A critical evaluation of the role of subcutaneous abatacept in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: patient considerations. Biologics 2014;8:41–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux‐Viala C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:964–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, Nayiager S, Wollenhaupt J, Durez P, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate‐naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1870–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kremer JM, Genant HK, Moreland LW, Russell AS, Emery P, Abud‐Mendoza C, et al. Effects of abatacept in patients with methotrexate‐resistant active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:865–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kremer JM, Russell AS, Emery P, Abud‐Mendoza C, Szechinski J, Westhovens R, et al. Long‐term safety, efficacy and inhibition of radiographic progression with abatacept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: 3‐year results from the AIM trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1826–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smolen J, Dougados M, Gaillez C, Poncet C, Le Bars M, Mody M, et al. Remission according to different composite disease activity indices in biologic‐naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept or infliximab plus methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63 Suppl:S477. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weinblatt M, Combe B, Covucci A, Aranda R, Becker JC, Keystone E. Safety of the selective costimulation modulator abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving background biologic and nonbiologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs: a one‐year randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Westhovens R, Kremer JM, Emery P, Russell AS, Li T, Aranda R, et al. Consistent safety and sustained improvement in disease activity and treatment response over 7 years of abatacept treatment in biologic‐naïve patients with RA. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68 Suppl 3:577. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, Luggen M, Sherrer Y, Kremer J, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1114–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schiff M, Pritchard C, Huffstutter JE, Rodriguez‐Valverde V, Durez P, Zhou X, et al. The 6‐month safety and efficacy of abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who underwent a washout after anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapy or were directly switched to abatacept: the ARRIVE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1708–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Zhao C, et al. Head‐to‐head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schiff M, Weinblatt M, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Elegbe A, et al. Head‐to‐head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab on background methotrexate in RA: two year results from the AMPLE study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72 Suppl 3:64. 22562973 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Elegbe A, et al. Head‐to‐head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two‐year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wells G, Li T, Maxwell L, Maclean R, Tugwell P. Determining the minimal clinically important differences in activity, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:280–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reilly MC, Brown MC, Brahant Y, Gerlier L, Tan SC, Sandborn WJ. Defining the minimally important difference for WPAI. CD scores: what is a relevant impact on work productivity in active Crohn's disease. Gut 2007;56 Suppl 3:159. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wells G, Li T, Maxwell L, Maclean R, Tugwell P. Responsiveness of patient reported outcomes including fatigue, sleep quality, activity limitation, and quality of life following treatment with abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, Kirwan JR, Kvien TK, Tugwell PS, et al. It's good to feel better but it's better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible: response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1720–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pollard L, Choy EH, Scott DL. The consequences of rheumatoid arthritis: quality of life measures in the individual patient. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:S43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirwan JR, Hewlett SE, Heiberg T, Hughes RA, Carr M, Hehir M, et al. Incorporating the patient perspective into outcome assessment in rheumatoid arthritis: progress at OMERACT 7. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rupp I, Boshuizen HC, Jacobi CE, Dinant HJ, van den Bos GA. Impact of fatigue on health‐related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, Songcharoen S, Berman A, Nayiager S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi‐centre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1096–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kremer JM, Genant HK, Moreland LW, Russell AS, Emery P, Abud‐Mendoza C, et al. Results of a two‐year followup study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who received a combination of abatacept and methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:953–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Genovese MC, Covarrubias A, Leon G, Mysler E, Keiserman M, Valente R, et al. Subcutaneous abatacept versus intravenous abatacept: a phase IIIb noninferiority study in patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:2854–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Kavanaugh AF, Chartash EK, Segurado OG. Long term efficacy and safety of adalimumab plus methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: ARMADA 4 year extended study. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:753–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, Kavanaugh A, Kupper H, Liu S, Guerette B, et al. Clinical, functional, and radiographic benefits of longterm adalimumab plus methotrexate: final 10‐year data in longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1487–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strand V, Rentz AM, Cifaldi MA, Chen N, Roy S, Revicki D. Health‐related quality of life outcomes of adalimumab for patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomized multicenter study. J Rheumatol 2012;39:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chaparro del Moral R, Rillo OL, Casalla L, Moron CB, Citera G, Cocco JA, et al. Work productivity in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship with clinical and radiological features. Arthritis 2012;2012:137635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, Young A, Singh A, Anis AH. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire: general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hazes JM, Taylor P, Strand V, Purcaru O, Coteur G, Mease P. Physical function improvements and relief from fatigue and pain are associated with increased productivity at work and at home in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with certolizumab pegol. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1900–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: benefit over low disease activity in patient‐reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Improvements in patient pain over 2 years in responder and non‐responder patient subgroups, defined by clinical response criteria: (A) CDAI LDA, (B) CDAI remission, and (C) Boolean remission.