ABSTRACT

There is a growing interest in applying tobacco agroinfiltration for recombinant protein production in a plant based system. However, in such a system, the action of proteases might compromise recombinant protein production. Protease sensitivity of model recombinant foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) virus P1-polyprotein (P1) and VP1 (viral capsid protein 1) as well as E. coli glutathione reductase (GOR) were investigated. Recombinant VP1 was more severely degraded when treated with the serine protease trypsin than when treated with the cysteine protease papain. Cathepsin L- and B-like as well as legumain proteolytic activities were elevated in agroinfiltrated tobacco tissues and recombinant VP1 was degraded when incubated with such a protease-containing tobacco extract. In silico analysis revealed potential protease cleavage sites within the P1, VP1 and GOR sequences. The interaction modeling of the single VP1 protein with the proteases papain and trypsin showed greater proximity to proteolytic active sites compared to modeling with the entire P1-polyprotein fusion complex. Several plant transcripts with differential expression were detected 24 hr post-agroinfiltration when the RNA-seq technology was applied to identify changed protease transcripts using the recently available tobacco draft genome. Three candidate genes were identified coding for proteases which included the Responsive-to-Desiccation-21 (RD21) gene and genes for coding vacuolar processing enzymes 1a (NbVPE1a) and 1b (NbVPE1b). The data demonstrates that the tested recombinant proteins are sensitive to protease action and agroinfiltration induces the expression of potential proteases that can compromise recombinant protein production.

KEYWORDS: agroinfiltration, cysteine proteases, foot-and-mouth disease, proteases, recombinant protein production, tobacco, VP1 protein

Introduction

In 2014, an experimental drug, called “ZMapp,” was used to treat 2 medical workers who had contracted the deadly Ebola virus. The unique characteristic of ZMapp is that its constituents have been produced in Nicotiana benthamiana plants.1 N. benthamiana is a model plant species widely used for the transient expression of proteins. Tobacco is sometimes compared to the role that the white mouse has played in mammalian studies.2-5 The N. benthamiana genome sequence has further potential to be useful for gene mining, construct design, and for the assessment of target and non-target gene silencing.2 A future prospect is also applying RNA-Seq data to fully annotate the tobacco genome and characterize the transcriptome.2 The large leaves of N. benthamiana and its susceptibility to a variety of pathogens have been harnessed as a means to transiently express proteins, using either engineered viruses or Agrobacterium tumefaciens.6 Due to a lower content of secondary compounds interfering in the protein purification process, N. benthamiana has been previously applied as a model plant species for heterologous protein expression.7 It has also been included as a tool in platforms for the production of recombinant proteins for comparative analyses.8

Due to proteolysis caused by protease action, plant-expressed recombinant proteins can possibly undergo either complete or partial proteolytic degradation.9-11 Such degradation can ultimately result in proteins with altered biological activity or no protein production at all.12,13 The identification of such proteases involved, particularly in Nicotiana species, has therefore been the subject of several recent investigations. The majority of protease families, which might compromise recombinant protein production in Nicotiana species, belong to the aspartic and cysteine protease (papain-like) families and, to a lesser extent, the serine and metallo-protease families.14,15 There is further evidence that such recombinant protein degradation might occur during the extraction process ex vivo as a result of proteases being released during the tissue disruption process.16 However, almost all protease families have also been associated with plant senescence.17 In Nicotiana species, the majority of these proteases are of aspartic or cysteine-type and, to a lesser extent, of serine and metallo-type.18 However, the N. benthamiana leaf contains less protease activity than a N. tabacum leaf and is therefore preferred for agroinfiltation.15 It has been recently reported that agroinfiltration can significantly alter the distribution of cysteine (C1A) and aspartate (A1) protease along the leaf age gradient in N. benthamiana. This was further related to the level of proteolysis in whole-cell and apoplast protein extracts.19 Improvements have been found for various recombinant proteins when protease activity was altered including: bovine serum albumin (BSA), human serum immunoglobulins G (hIgGs), anti-HIV antibodies (2F5) as well as human protease inhibitor, α1-antitrypsin.13,20,21 However, there is a lack of detailed information on whether induction of plant-derived proteases is among the host responses to agroinfiltration.22 Therefore, the identification of proteases induced by agroinfiltration might be a key step in the improvement of recombinant protein production when applying the agroinfiltration technique.

The purpose of this study was to investigate protease-sensitivity of various model recombinant proteins with the aim to first establish any protease sensitivity and secondly to identify possible proteases expressed as a consequence of the agroinfiltration process. We specifically hypothesized that cysteine proteases are among these expressed proteases following agroinfiltration based on a previous finding in our group that recombinant E. coli glutathione reductase (GOR) was more stable in agroinfiltrated tobacco leaves engineered with a rice cysteine protease inhibitor (OC-I).23 In our study, we determined the inherent vulnerabilities of recombinant model proteins derived from the foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) which are the VP1 and P1-polyprotein (P1) as well as Escherichia coli (E. coli)-derived glutathione reductase (GOR) proteins toward proteolysis. We also applied protein modeling to investigate how interacting residues within VP1 would interact with a cysteine and serine protease (papain and trypsin) either individually or as part of a P1-polyprotein to obtain more information on VP1 stability against protease action. Finally by applying transcriptomic profiling using RNA-Seq, N. benthamiana leaves were screened for the transcription of proteases due to agroinfiltration. We found that the recombinant model proteins used were sensitive to cysteine and serine protease degradation and that expression of several types of proteases, including cysteine proteases, increased due to the agroinfiltration of tobacco leaves.

Results

Protease sensitivity of model recombinant proteins

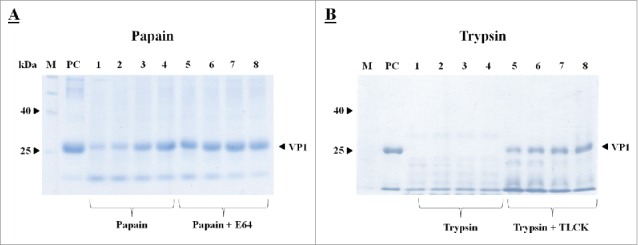

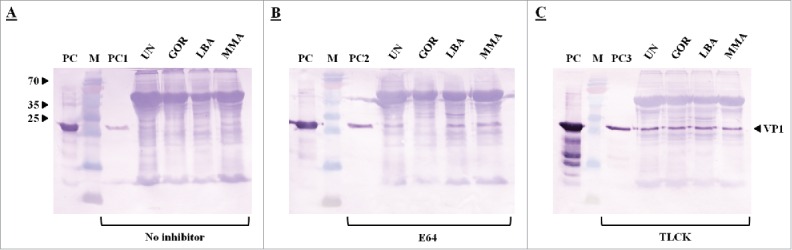

Since VP1 was used in the study as one of the model recombinant proteins, the VP1 protein (Fig. 1) was first treated with either a cysteine (papain) or serine (trypsin) protease to determine VP1 sensitivity to protease treatment (Fig. 2). Both proteases degraded VP1 when determined by SDS-PAGE analysis, but with more severe VP1 degradation occurring when treated with trypsin (Fig. 2b). Less degradation occurred when either E64, a cysteine protease inhibitor, or TLCK, a trypsin inhibitor, was added to the reaction mixture (Fig. 2a, b). In order to also investigate the influence of proteases ex planta, VP1 was further treated using tobacco extracts with and without the addition of a protease inhibitor (Fig. 3). VP1 band intensity changed indicating possible protease action; also, some smaller sized bands cross-reacted with the His-antiserum possibly indicating some proteolytic degradation products (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, a tobacco extract containing a protease inhibitor resulted in less VP1 degradation (Fig. 3b, c).

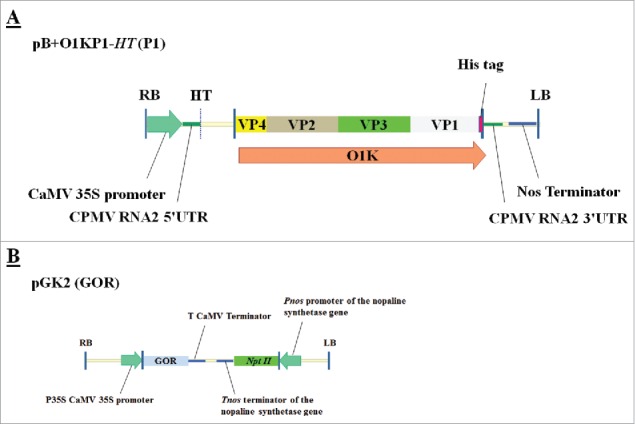

Figure 1.

(A) Binary vector pB+O1KP1-HT harbouring the coding sequence O1K under control of a duplicated cauliflower mosaic viSSSrus 35S promoter and a t-nos terminator sequence and O1K consisting of fused VP1 - 4 coding sequences with VP1 fused to a 6xHis coding sequence (P1-polyprotein). (B) Schematic representation of GOR T-DNA used for agroinfiltration. Binary vector pGK2 (GOR) harbouring the GOR gene. RB and LB refers to the right and left border, respectively. NptII refers to the neomycin phosphotransferase gene which confers kanamycin resistance.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of VP1 susceptibility to papain (A) and trypsin (B). Samples were analyzed on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. All sample lanes contain 44 µg of VP1 treated with either papain or trypsin. Lanes 1 to 4 contain either papain (0.2 µg, 0.3 µg, 0.4 µg and 0.5 µg) or trypsin (0.2 µg, 0.3 µg, 0.4 µg and 0.5 µg). Lanes 5 to 8 contain VP1 treated with papain (0.2 µg, 0.3 µg, 0.4 µg and 0.5 µg) together with the cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (1 µM) or VP1 treated trypsin (0.2 µg, 0.3 µg, 0.4 µg and 0.5 µg respectively) together with the serine protease inhibitor TLCK (40 mM). PC (44 µg purified VP1) represents the positive control and M represents a pre-stained protein ladder.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of VP1 susceptibility with Anti-His antiserum of exogenous VP1 incubated with N. benthamiana leaf extracts with or without protease inhibitors. Lanes 1-4 represent 15 µg of VP1 treated with a tobacco extract (230 µg) with either no protease inhibitor (A), a cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (100 µM) (B) or a serine protease inhibitor TLCK (100 µM) (C) added to Arakawa extraction buffer. Lanes UN, GOR, LBA and MMA represent VP1 (15 µg) incubated with tobacco extract only, GOR agroinfiltrated extract, LBA agroinfiltrated extract and MMA agroinfiltrated extract, respectively. Lane M represents a Pageruler pre-stained protein ladder. PC represents VP1 positive control (60 µg). PC1, PC2 and PC3 represent 15 µg of VP1 incubated with Arakawa extraction buffer.

Protease cleavage sites

In a second step we investigated in vitro if model recombinant proteins VP1, GOR as well as P1-polyprotein (VP2 - 4) have proteolytic cleavage sites (Table 1). Subsite nomenclature was assumed from a model created by Schechter and Berger (1967, 1968) where the amino acid residues in a substrate undergoing proteolytic cleavage are designated P1, P2, P3, P4, etc., in the N-terminal direction from the cleaved bond. VP1 was particularly susceptible to papain cleavage with 3 papain amino acid sites (C25, H159, N175) involved in the interaction. When amino acid T (threonine) was used in the P1 substrate position, 62 cleavage sites were found in the polyprotein (Table 1, highlighted in yellow). Within the GOR sequence, 34 cleavage sites were found when amino acid G (glycine) was used in the P1 substrate position (Table 1, highlighted in yellow). Cleavages sites with amino acid W (tryptophan) in the P1 substrate position were, however, not highly abundant in either the P1-polyprotein or GOR sequences with only 3 and 2 sites, respectively, being present (Table 1, highlighted in turquoise). Papain cleaves at TL213 at the end of the VP1 sequence as well as AE220 at the end of the VP3 sequence while cathepsin L cleaves at KE218 at the end of the VP2 sequence (Table 3.1, highlighted in gray). Cathepsin H further cleaves VP1 at L213 and at R478 of the GOR sequence (Table 1, highlighted in gray). Cathepsin H cleavage sites, with K and L at the P1 substrate position, were further abundant for GOR and VP1 sequences with 34 and 33 sites, respectively (Table 1, highlighted in yellow). VP1 seems to be particular susceptible to cathepsin H cleavage with a total of 61 potential cleavage sites (Table 1, highlighted in yellow).

Table 1.

In silico proteolytic cleavage site analysis for P1-polyprotein, VP1 and glutathione reductase (GOR) using primarily the P1 and P2 substrate positions within amino acid sequences.

| Protease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cysteine protease | P1-polyprotein | GOR | Cleavage | Preferential Cleavage |

| Papain (C25, H159, N175) | VP1 chain – AR157, 200, LR67, 145, YR179, TR114, 172, PR189, DR38, SR138, QR26VP2 chain – TR18, 54, MR102, PR151, DR13, ER60VP3 chain – R56, R120, R212, R218, PR34, DR72VP4 chain – none | AR37, 45, LR224, 478, IR127, 218, WR97, SR109 | AR↓, VR↓, LR↓, IR↓, FR↓, WR↓, YR↓, TR↓, MR↓, PR↓, DR↓, SR↓, ER↓, QR↓ | (A, V, L, I, F, W, Y – hydrophobic amino acids in P2 position)(↓ no Val after cleavage sites) |

| VP1 chain - VK81, 210, IK169, MK181, EK96, QK204VP2 chain – FK63, IK198, DK2, SK217, QK134VP3 chain – AK84, 118, TK67, PK20, 134, SK154VP4 chain – SK70 | VK252, 255, 324, 397, 452, LK247, IK100, YK357, TK120, 296, 412, 457, MK420, PK66, 137, DK221, 310, SK212, 361, EK102 | AK↓, VK↓, LK↓, IK↓, FK↓, WK↓, YK↓, TK↓, MK↓, PK↓, DK↓, SK↓, EK↓, QK↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – IH195, YH108, PH123, SH59, QH29VP2 chain – AH157, VH174, TH65, PH145, DH87VP3 chain – AH141, LH108, IH144, TH191 VP4 chain – TH58 | AH351, VH75, IH389, 434, 467, YH408, MH80, PH151, 164, DH82, SH52, 122, 374 | AH↓, VH↓, LH↓, IH↓, FH↓, WH↓, YH↓, TH↓, MH↓, PH↓, DH↓, SH↓, EH↓, QH↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AE184, VE16, LE77, TE175, 198, PE95VP2 chain – AE40, 59, VE108, LE11, 52, 82, TE5, 192, PE128, PE137, EE6VP3 chain – AE49, 146, 176, 220, FE58, 210, ME131VP4 chain – none | AE41, VE50, 201, LE184, 239, IE124, 141, 394, FE355, TE236, 384, DE317, 386, 442, SE77, 472, EE185, 237, 428, 473, QE5 | AE↓, VE↓, LE↓, IE↓, FE↓, WE↓, YE↓, TE↓, ME↓, PE↓, DE↓, SE↓, EE↓, QE↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – IN49, FN164, YN131, TN103, PN91, 143, DN100, EN17, QN46VP2 chain – AN202, VN166, 190, IN149, FN117, TN153, 207, PN47VP3 chain – LN152, IN106, FN31, TN43, 179, SN88VP4 chain – IN23, TN61, DN41, SN48, QN13, 32, 64 | AN425, LN111, 301, FN95, WN71, YN365, TN233, PN294, DN462, EN240, 395, QN116 | AN↓, VN↓, LN↓, IN↓, FN↓, WN↓, YN↓, TN↓, MN↓, PN↓, DN↓, SN↓, EN↓, QN↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AQ153, IQ25, TQ23, PQ45VP2 chain – VQ57, IQ133, YQ139, TQ27, PQ196, DQ170VP3 chain – AQ76, 96, VQ181, FQ188, TQ100VP4 chain – YQ31, TQ37, MQ28, SQ12, QQ29 | LQ445, IQ306, FQ182, 319, YQ115, MQ436, PQ6,9, SQ167 | AQ↓, VQ↓, LQ↓, IQ↓, FQ↓, WQ↓, YQ↓, TQ↓, MQ↓, PQ↓, DQ↓, SQ↓, EQ↓, QQ↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AS69, FS74, YS137, TS3, 162, PS58, ES7VP2 chain – VS44, TS24, 49, 72, PS216, DS74, 97, QS28VP3 chain – AS172, 204, LS163, FS158, YS102, MS80, 87, DS70VP4 chain – AS73, IS44, FS69, 77, TS56, SS6, 74, QS5, 15 | AS20, 35, 172, VS108, 143, 264, LS207, 259, 299, IS231, FS249, 373, YS400, TS134, 177, 214, 402, PS89, 161, DS228, 360, SS471, ES51, 166 | AS↓, VS↓, LS↓, IS↓, FS↓, WS↓, YS↓, TS↓, MS↓, PS↓, DS↓, SS↓, ES↓, QS↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AT128, 171, VT12, 43, 174, LT87, 113, YT120, TT2, 13, 14, 102, PT105, 161, 197, ST70, ET22, 185, QT212VP2 chain – AT38, VT33, 71, 110, LT16, 95, 141, 188, IT159, WT178, TT8, 17, 23, 26, MT155, PT85, 206, ST25, ET7, 53VP3 chain – VT16, 65, IT190, FT42, 112, 156, YT99, 168, 170, TT17, 66, 178, PT53, 115, DT149, ET177VP4 chain – AT9, TT55, 60, DT36, 54, ST52, 57 | AT156, 456, VT267, 411, LT119, 339, 383, IT176, FT133, 404, YT148, MT277, PT139, 369, 469, ST162, 232, 401, QT307 | AT↓, VT↓, LT↓, IT↓, FT↓, WT↓, YT↓, TT↓, MT↓, PT↓, DT↓, ST↓, ET↓, QT↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AG5, VG63, YG19, 166, EG84VP2 chain – AG212, VG31, 113, 164, FG76, YG35, 92, SG45, 50, EG193VP3 chain – AG93, 206, YG12, 27, TG113, 150, PG39, 129, DG10, 196, SG103, EG59, QG182VP4 chain – AG3, LG39, FG81, TG10, 19, SG16, 45, 78, EG50 | AG16, 196, 204, 242, 346, VG62, 194, 330, 381, 432, LG43, 55, 174, 210, 304, 439, IG27, 290, 378, YG86, 392, TG157, MG454, PG170, 188, 271, DG179, SG31, 144, 260, EG92, QG10, 437, 446 | AG↓, VG↓, LG↓, IG↓, FG↓, WG↓, YG↓, TG↓, MG↓, PG↓, DG↓, SG↓, EG↓, QG↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – YF73, SF34, 163VP2 chain – LF67, 143, FF62, PF162, DF42, SF75, EF214, QF116, 147 VP3 chain – VF30, LF187, IF3, TF54, 90, 157, MF111, DF209, QF77VP4 chain – AF76, LF80, WF68 | AF132, VF372, LF354, FF181, DF460, SF226, 403, EF78, 318 | AF↓, VF↓, LF↓, IF↓, FF↓, WF↓, YF↓, TF↓, MF↓, PF↓, DF↓, SF↓, EF↓, QF↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – noneVP2 chain – PW177VP3 chain – EW147VP4 chain – DW67 | LW287, MW70 | AW↓, VW↓, LW↓, IW↓, FW↓, WW↓, YW↓, TW↓, MW↓, PW↓, DW↓, SW↓, EW↓, QW↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AY107, VY130, LY178, YY72, TY71, 186, PY119VP2 chain – AY100, VY91, 200, LY138, TY34, SY98, QY171VP3 chain – AY125, VY26, YY98, TY169, PY63, 161, DY167, QY97, 101VP4 chain – YY26, QY30 | AY106, IY114, 327, TY399, MY407, DY23, 85, 364, SY21, EY356 | AY↓, VY↓, LY↓, IY↓, FY↓, WY↓, YY↓, TY↓, MY↓, PY↓, DY↓, SY↓, EY↓, QY↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – AL98, 117, VL126, 151, LL66, 177, 192, IL51, TL61, 159, 213, PL112, 191, DL53, 76, 86, 148, EL176VP2 chain – LL10, 81, 122, IL15, TL9, 142, 179, PL187, SL94, EL83, 129, 137, QL140VP3 chain – AL199, VL74,202, LL45, FL55, 91, YL162, SL81, EL211, QL37VP4 chain – AL83, LL84, QL38 | AL209, 337, VL223, 246, LL286, 338, IL153, TL258, ML444, DL298, SL173, 215, 300, EL42, 186, 238, QL183 | AL↓, VL↓, LL↓, IL↓, FL↓, WL↓, YL↓, TL↓, ML↓, PL↓, DL↓, SL↓, EL↓, QL↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – LM54, IM36VP2 chain – AM125, YM101VP3 chain – FM110, YM122, DM79, SM34VP4 chain – YM27 | VM69, 276, 419, LM216, FM79, TM278, PM406, SM229, 265, EM202, 443 | AM↓, VM↓, LM↓, IM↓, FM↓, WM↓, YM↓, TM↓, MM↓, PM↓, DM↓, SM↓, EM↓, QM↓ | ||

| Cathepsin L | VP1 chain – KR182, KH82, KQ203, KA97, 110, 170VP2 chain – KK3, KR135, KE218, KT4, KG89 VP3 chain – KH85, KT21, 68, 135, KF155, KA119, 194VP4 chain – KL71 | KK67, 146, 256, KR103, 413, KE101, 253, 358, 427, KS121, KT213, 257, 398, 415, KG311, 325, KF94, 248, KY147, KA336, 458, KL54, 303, 349, 362, KM453 | KK↓, KR↓, KH↓, KE↓, KN↓, KQ↓, KS↓, KT↓, KG↓, KF↓, KW↓, KY↓, KA↓, KL↓, KM↓, |

|

| VP1 chain – noneVP2 chain – WT178VP3 chain – noneVP4 chain – WF68 | WR97, WN71, WA288 | WK↓, WR↓, WH↓, WE↓, WN↓, WQ↓, WS↓, WT↓, WG↓, WF↓, WW↓, WY↓, WA↓, WL↓, WM↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – HK109, 202, HE83, HT30, 60VP2 chain – HK88, 175, HQ146, HT22, HL66, 80VP3 chain – HG192, HF109, HA145, HM86VP4 chain – HT59 | HK53, 390, HR352, HE165, HS76, HA83, 130, 409, HM435 | HK↓, HR↓, HH↓, HE↓, HN↓, HQ↓, HS↓, HT↓, HG↓, HF↓, HW↓, HY↓, HA↓, HL↓, HM↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – FI35VP2 chain – HI158, SI132, FI148VP3 chain – SI159VP4 chain – SI21, II22 | HI123, 152, 313, PI377, YI198, VI26, 99, II126, LI154, MI217, 230, 279 | KI↓, HI↓, DI↓, SI↓, PI↓, FI↓, WI↓, YI↓, VI↓, II↓, LI↓, MI↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – KV42, 155, DV32, PV11, 209, FV40, WV89, IV206, LV62VP2 chain – KV173, 199, HV210, DV107, SV30, FV43, 163, WV70, VV56, 181, LV123, 180, MV126VP3 chain – KV29, DV47, 174, PV5, 25, 215, WV184, YV64, VV201, LV15, MV123VP4 chain – none | KV68, 222, DV282, 332, SV191, PV275, 341, YV107, VV49, 371, 431, IV193, 315, LV25, 475, MV266, 422 | KV↓, HV↓, DV↓, SV↓, PV↓, FV↓, WV↓, YV↓, VV↓, IV↓, LV↓, MV↓ | ||

| Cathepsin H | VP1 chain – R26, 27, 38, 67, 114, 124, 135, 138, 145, 157, 172, 179, 182, 189, 200, K41, 81, 96, 109, 154, 169, 181, 202, 204, 210, F34, 39, 73, 163, W88, L51, 53, 61, 65, 66, 76, 86, 98, 112, 115, 117, 126, 144, 148, 151, 159, 176, 177, 191, 192, 213, Y18, 71, 72, 107, 119, 130, 136, 165, 178, 186 VP2 chain – R13, 18, 54, 60, 77, 102, 135, 151, 167, K2, 3, 63, 88, 134, 172, 175, 198, 217, F42, 61, 62, 67, 75, 116, 143, 147, 162, 214, W69, 105, 177, L9, 10, 15, 51, 66, 80, 81, 83, 94, 121, 122, 129, 137, 140, 142, 179, 187, Y34, 36, 91, 98, 100, 138, 168, 171, 200 VP3 chain – R34, 40, 56, 72, 120, 212, 218, K20, 28, 67, 84, 118, 134, 154, 193, 207, F3, 30, 41, 54, 57, 77, 90, 109, 111, 155, 157, 187, 209, W147, 183, L14, 37, 44, 45, 55, 74, 81, 91, 94, 107, 151, 162, 186, 199, 202, 211, 213, Y11, 26, 63, 97, 98, 101, 121, 125, 161, 167, 169 VP4 chain – K70, F68, 76, 80, W67, L38, 71, 79, 83, 84, Y25, 26, 30 |

R3, 37, 38, 45, 97, 103, 109, 127, 189, 218, 224, 272, 291, 347, 352, 413, 478K53, 66, 67, 93, 100, 102, 120, 137, 145, 146, 212, 221, 247, 252, 255, 256, 296, 302, 310, 324, 335, 348, 357, 361, 390, 397, 412, 414, 416, 420, 426, 429, 452, 457F78, 87, 94, 132, 180, 181, 226, 248, 318, 354, 372, 403, 447, 460,W70, 96, 287L24, 33, 42, 54, 110, 118, 153, 173, 183, 186, 206, 209, 215, 223, 238, 246, 258, 261, 273, 285, 286, 298, 300, 303, 337, 338, 349, 353, 362, 382, 438, 444, 474Y21, 23, 85, 106, 114, 147, 197, 327, 356, 364, 391, 399, 407 | R↓, K↓, F↓, W↓, L↓, Y↓ | |

| Cathepsin B | VP1 chain – RR27VP2 chain – noneVP3 chain – noneVP4 chain – none | RR38 | RR↓ |

|

| VP1 chain – RP190, HP196, NP104, TP44, AP94, VP57, 90, 142, LP118, 160VP2 chain – KP176, NP150, GP46, FP144, 215, AP186, 195, 205, VP127, 161, LP84, VP3 chain – DP19, 24, EP132, NP32, TP136, GP114, AP127, VP62, IP160, LP38,VP4 chain – SP7 | KP138, HP375, 468, DP136, EP6, QP8, TP163, 340, 405, GP11, FP88, AP150, VP65, IP169, 280, 368, LP187, 274, MP160 | KP↓, RP↓, HP↓, DP↓, EP↓, NP↓, QP↓, SP↓, TP↓, GP↓, FP↓, WP↓, YP↓, AP↓, VP↓, IP↓, LP↓, MP↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – GE6, GG20, 64, GA93, 167, GL65VP2 chain – GR77, GH21, GE213, GN114, GS93, GG119, GP46, GW105, GY36, GA194, GL51VP3 chain – GK193, 207, GR40, GT104, GG13, GP114, GT104, GG13, GP114, GY11, GL94, 151, GM130VP4 chain – GN17, GQ4, GS11, 20, 47, 51, GG46, GL79 | GK93, 145, 335, GR189, 272, 347, GH129, 312, GS30, 211, GT57, GG29, 32, 56, 158, GP11, GF87, 180, 447, GY197, GA17, 44, 171, 195. 455, GL33, 261, 382, 438, GM159 | GK↓, GR↓, GH↓, GE↓, GN↓, GQ↓, GS↓, GT↓, GG↓, GP↓ GF↓, GW↓, GY↓, GA↓, GL↓, GM↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – NQ47, NT101, NG92, 132, NP104, NY18, 165, NL144VP2 chain – NR167, NQ115, NT48, 191, NG20, 104, 118, NP150, NM154 VP3 chain – NQ36, NS153, NT89, NP32, NL44, 107VP4 chain – NE49, NN24, 65, NQ14, NS33, NT18, 62, NY25, NA42 |

NK302, 426, NN117, 366, NT72, 295, 321, 463, NW96, NA112, 241, NL118 | NK↓, NR↓, NH↓, NE↓, NN↓, NQ↓, NS↓, NT↓, NG↓, NP↓ NF↓, NW↓, NY↓, NA↓, NL↓, NM↓ | ||

| VP1 chain – RH201, RN139, RQ28, RT158, RG146, RP190, RY136, RA183, RL115, RM180VP2 chain – RE136, RN19, RT152, RF61, RY168VP3 chain – RN35, RF41, RY121, RA219, RL213VP4 chain – none | RK348, 414, RH219, RQ4, RS225, RG128, RA39, R110, 273, 353 | RK↓, RH↓, RE↓, RN↓, RQ↓, RS↓, RT↓, RG↓, RP↓ RF↓, RW↓, RY↓, RA↓, RL↓, RM↓ | ||

| Legumain | VP1 chain – TN103VP2 chain – AN202, TN153, 207VP3 chain – TN43, 179, LN152VP4 chain – TN61 | AN425, TN233, 322, LN111, 301 | AAN↓, AN↓, TN↓, LN↓ | Based on optimal sequences for schistosome (C197, N197C) and human legumains, and cruzain 49 |

| Serine protease | ||||

| Trypsin (H57, D102, G193, S195) | VP1 chain – K41, 81, 96, 109, 154, 169, 181, 202, 204, 210, R26, 27, 38, 67, 114, 124, 135, 138, 145, 157, 172, 179, 182, 189, 200 VP2 chain – K2, 3, 63, 88, 134, 172, 175, 198, 217, R13, 18, 54, 60, 77, 102, 135, 151, 167 VP3 chain – K20, 28, 67, 84, 118, 134, 154, 193, 207, R34, 40, 56, 72, 120, 212, 218 VP4 chain – K70 |

K53, 66, 67, 93, 100, 102, 120, 137, 145, 146, 212, 221, 247, 252, 255, 256, 296, 302, 310, 324, 335, 348., 357, 361, 390, 397, 412, 414, 416, 420, 426, 429, 452, 457, R3, 37, 38, 45, 97, 103, 109, 127, 189, 218, 224, 272, 291, 347, 352, 413, 478 | K↓, R↓ |

Amino acids are designated by the single-letter code

Cleavage sites are designated by arrows (↓)

Numbers appearing after amino acids refer to the position of potential cleavage

Highly abundant cleavage sites are highlighted in yellow

Highly scarce cleavage sites are highlighted in turquoise

Cleavage sites occurring at the end of a protein sequence are highlighted in gray

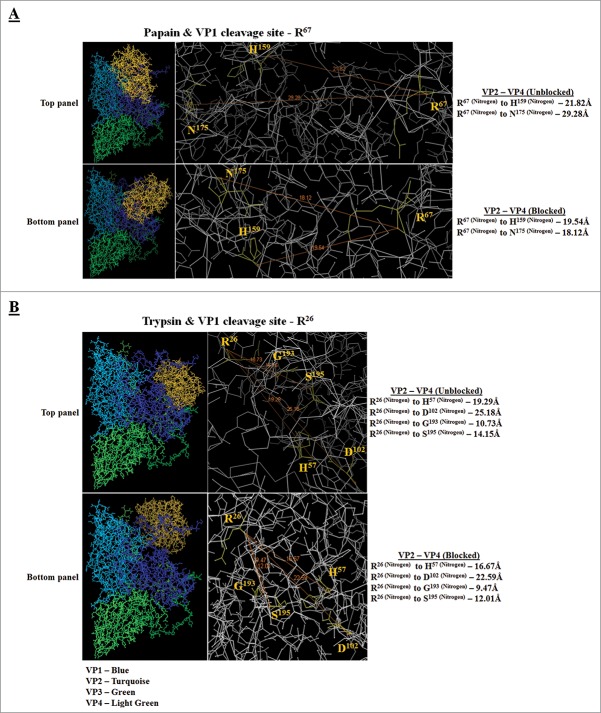

To further determine VP1 susceptibility to papain, or trypsin action, ZDOCK protein modeling was then applied between VP1 and the 2 proteases and the distances (in Ångstroms) between interacting VP1 and protease residues (VP1 cleavage site R67 for papain and VP1 cleavage site R26 for trypsin) were determined. The distance in Ångstroms (Å) decreased when VP1 was not modeled together with the additional capsid proteins (VP2, VP3 and VP4) indicating higher VP1 sensitivity to protease action (Fig. 4, bottom panels). In contrast, when all other binding sites for VP2, VP3 and VP4 within the P1-polyprotein were permitted in the interaction model with the protease, the distance increased with a weaker VP1-protease interaction and better stability of VP1 (Fig. 4, top panels).

Figure 4.

Protein docking model of single VP1 with papain and trypsin. (A) Docking model of VP1 (cleavage site - R67) and papain. (B) Docking model of VP1 (cleavage site - R26) and trypsin. Unblocked means all other binding sites (capsid proteins VP2, VP3 and VP4) within the P1-polyprotein were permitted in the interaction model. Blocked means all other binding sites (capsid proteins VP2, VP3 and VP4) within the P1-polyprotein were blocked in the interaction model. Distances between interacting residues are given in Ångstroms (Å).

Transcriptome analysis of agroinfiltrated tobacco leaves

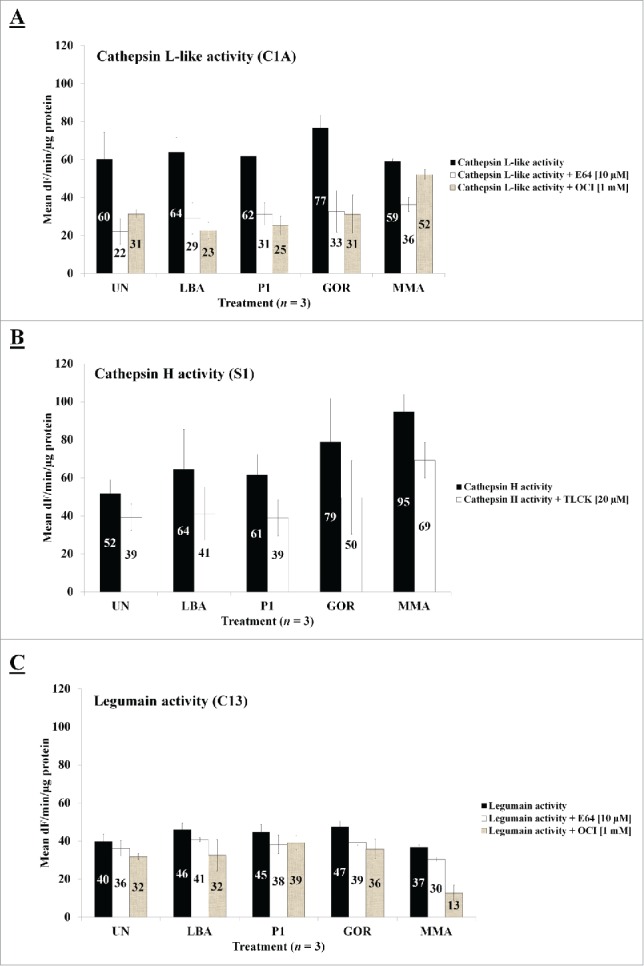

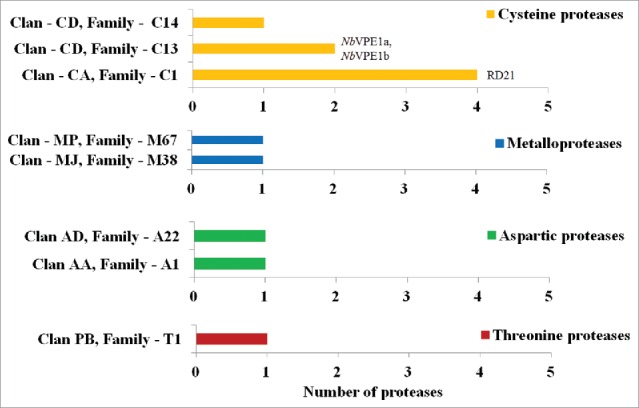

Since we found no significant statistical differences in proteolytic activities between experimental (LBA, P1, GOR) and control (UN & MMA) groups when various cysteine protease activities (cathepsin L and H, legumain proteolytic activities) were measured with fluorogenic substrates 24 hr post infection (pi) (Fig. 5), possible expression of proteases due to agroinfiltration was also investigated using RNA-seq analysis. When a limit of at least 2-times higher protease expression in agroinfiltrated tissues based on FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) values was set, the most expressed proteases were cysteine proteases (7 proteases) belonging to 3 different cysteine protease families (C1, C13 and C14) (Fig. 6, Table 2) with most cysteine proteases belonging to the C1 family of cysteine proteases (4 proteases). Further, other proteases expressed as a consequence of agroinfiltration belonged to metallo-proteases (2 proteases) in 2 families (M38 and M67), aspartic proteases (2 proteases) in 2 families (A1 and A22) and threonine proteases (1 protease) in 1 family (T1) (Table 2). In comparison to all other proteases, the cysteine protease RD21 (XM_009614860.1) was the highest expressed cysteine protease. Agroinfiltration increased expression of this cysteine protease about 4-times (Table 2). The protease most induced was NbVPE-1b, a vacuolar processing enzyme, belonging to the C13 cysteine protease family (Table 2). This protease was expressed about 95-times higher (based on FPKM-values) in agroinfiltrated leaves than in non-infiltrated leaves. Such a high expression was also found when tobacco leaves were infiltrated with a construct to produce the P1-polyprotein (75-times) and with a construct for GOR production (92-times). For all other identified proteases belonging to different classes, expressions in non-treated leaves were much lower compared to agroinfiltration-induced expression which was in the range of 2-30-times more. This increase was irrespective of infiltration with Agrobacterium alone or with a construct allowing P1-polyprotein or GOR expression.

Figure 5.

Protease activities of cathepsin L-like, cathepsin H-like and legumain-like in control (UN & MMA) and experimental groups (LBA, P1 and GOR). (A) Cathepsin L-like activity, (B) cathepsin-H like activity, (C) legumain-like activity. The y-axis represents the mean activities expressed as fluorescence units (dF) per min per µg protein. Mean activities of 3 biological replicates are shown within bars. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 6.

Proteolytic class distribution bearing the clans and families of the 5 major classes of proteases in N. benthamiana from the MEROPS database found in RNA-Seq datasets and number of protease(s) identified in various classes to be expressed at 2-times higher based on FPKM values after agroinfiltration. Genes further validated by RT-qPCR (RD21 and NbVPE). Yellow – Cysteine proteases. Blue – Metalloproteases. Green – Aspartic proteases. Maroon – Threonine proteases.

Table 2.

Identification, expression and function of genes due to agroinfiltration.

| UN | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clan† | Family‡ | tracking_id | FPKM§ | LBA | P1 | GOR | Genbank Accession number | GenBank Description | TAIR locus name | Tair description |

| CA | C1 | Niben101Scf01369Ctg011:1023-3226 | 2.2 | 31.6 (14.3) | 17.5 (7.9) | 18.1 (8.2) | XM_009798142.1 | xylem cysteine proteinase 1-like | AT1G20850 | XCP2, XYLEM CYSTEINE PEPTIDASE 2 |

| Niben101Scf04007Ctg010:1046-4801 | 140.4 | 655.6 (4.6) | 577.1 (4.1) | 710.5 (5.06) | XM_009614860.1 | low-temperature-induced cysteine proteinase-like | AT1G47128 | RD21, RD21A, RESPONSIVE TO DEHYDRATION 21, RESPONSIVE TO DEHYDRATION 21A | ||

| Niben101Scf01701Ctg053:1304-2925 | 11.6 | 30.8 (2.6) | 36.9 (3.1) | 25.3 (2.2) | XM_009772991.1 | zingipain-2 | AT1G09850 | XBCP3, XYLEM BARK CYSTEINE PEPTIDASE 3 | ||

| Niben101Scf03514Ctg004:2555-6476 | 11.7 | 45.8 (3.9) | 45.8 (3.9) | 49.6 (4.2) | XM_009594290.1 | cysteine proteinase 3-like | AT5G60360 | AALP, ALEURAIN-LIKE PROTEASE, ALP, SAG2, SENESCENCE ASSOCIATED GENE2 | ||

| CD | C13 | Niben101Scf04539Ctg027:143-4747 | 7.1 | 44.4 (6.3) | 38.0 (5.3) | 40.9 (5.7) | AB181187.1 | NbVPE-1a mRNA for vacuolar processing enzyme 1a | AT4G32940 | GAMMA VACUOLAR PROCESSING ENZYME, GAMMA-VPE, GAMMAVPE |

| Niben101Scf04675Ctg067:1577-4581 | 7.6 | 726.7 (95.6) | 568.9 (74.9) | 699.1 (91.9) | AB181188.1 | NbVPE-1b mRNA for vacuolar processing enzyme 1b | AT4G32940 | GAMMA VACUOLAR PROCESSING ENZYME, GAMMA-VPE, GAMMAVPE | ||

| CD | C14 | Niben101Scf06902Ctg013:5476-8453 | 0.6 | 10.3 (17.1) | 8.1 (13.5) | 17.8 (29.6) | XM_009795875.1 | metacaspase-1 | AT1G02170 | ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA METACASPASE 1 |

| MJ | M38 | Niben101Scf09860Ctg01:1005-5383 | 1.9 | 18.5 (9.7) | 21.3 (11.2) | 24.0 (12.6) | XM_009796689.1 | Dihydro-pyrimidinase | AT5G12200 | PYD2, PYRIMIDINE 2 |

| MP | M67 | Niben101Scf07364Ctg013:20621-21147 | 20.9 | 110.7 (5.3) | 126.6 (6.0) | 116.0 (5.6) | XM_009779021.1 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 14 homolog | AT5G23540 | MOV34/MPN/PAD-1 FAMILY PROTEIN |

| AA | A1 | Niben101Scf08709Ctg013:6889-8887 | 1.7 | 4.8 (2.8) | 2.9 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.5) | XM_009764962.1 | aspartic proteinase PCS1-like | AT5G02190 | ASPARTIC PROTEASE 38, ATASP38 |

| AD | A22 | Niben101Scf08817Ctg011:344-1385 | 1.7 | 7.2 (4.2) | 7.9 (4.6) | 6.5 (3.8) | XM_009593783.1 | signal peptide peptidase-like 4 | AT1G01650 | SIGNAL PEPTIDE PEPTIDASE-LIKE 4, ATSPPL4 |

| PB | T1 | Niben101Scf07066Ctg019:2266-2528 | 14.6 | 59.2 (4.0) | 45.1 (3.1) | 63.7 (4.4) | XM_009797260.1 | proteasome subunit α type-7 | AT5G66140 | PAD2, PROTEASOME ALPHA SUBUNIT D2 |

Clan PB contains endopeptidases and self-processing proteins

For families C represents cysteine, M metallo, A aspartic, and T threonine

Increase in expression measured as fold increase of FPKM in brackets

Protease reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

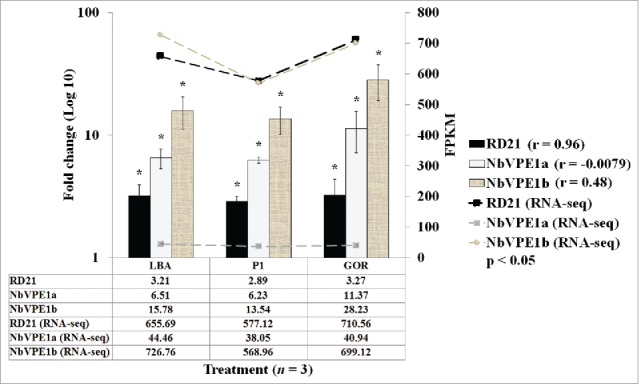

RT-qPCR was carried out to confirm the RNA-Seq data. Three sequences coding for cysteine protease-like proteins (RD21, NbVPE-1a and NbVPE-1b) were selected for confirmation. Significantly elevated gene expression was found in all experimental groups (LBA, P1 and GOR) relative to the control (UN), which was set at 1 (Fig. 7), in general accordance with the RNA-Seq data as shown by the line graphs of the 3 respective genes. There were statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the expression levels of the different genes assayed for (RD21, NbVPE-1a, NbVPE-1a). The highest fold increase due to agroinfiltration was also found for, NbVPE-1b, comparable to the RNA-Seq result. The discrepancy between the RNAseq and RT-qPCR data for NbVPE-1b can be accounted for by the reduced coverage within the RNA-seq datasets compared to the RT-qPCR data.

Figure 7.

Fold change and FPKM of gene expression of RD21 (black bars), NbVPE1a (gray bars) and NbVPE1a (canvas bars) in LBA, P1 and GOR experimental groups normalized to reference genes and relative to untreated control (UN) set at 1. Fold changes are represented on left y-axis as log 10 and samples are represented on x-axis. Error bars indicate standard error of mean (SEM) across 3 biological replicates. FPKM values of RD21 (black line), NbVPE1a (gray line) and NbVPE1b (canvas line) are represented on the right y-axis. ‘r’ refers to the Pearson correlation coefficient between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR gene expression measurements. Statistically significant differences between gene expression levels (RD21, NbVPE1a and NbVPE1a) in treatments (LBA, P1 and GOR) compared to control (UN) were determined by 2-factor ANOVA with replication (p-value< 0.001) and Bonferroni corrected post-hoc t-tests (p-value < 0.05) are represented as asterisks above graphs (*).

Discussion

The effect of proteases on recombinant protein stability in plant-based expression systems is a field of growing interest. Results in this study have clearly demonstrated that 3 selected recombinant proteins (P1-polyprotein, VP1 and GOR) are sensitive to protease action. Such action has also been recently associated with lower antigenicity when heterologous proteins were expressed in a plant host.13,21 Sensitivity of VP1 against proteases was further confirmed when treated with a protease-containing tobacco extract and when in silico proteolytic site analysis was carried out. In particular, cathepsin H-like cysteine proteases might play a major role in VP1 degradation. Our study also provided evidence that proteins, like VP1, are less susceptible to protease degradation when part of a polyprotein.24 Such greater VP1 stability and better processing when expressed in tobacco as a P1-polyprotein, has previously been found.25 Less protease sensitivity was also identified in our protein docking experiments when the distance between interacting residues of VP1 and proteases increased as a result of being part of a polyprotein.

Besides establishing protease sensitivity of model recombinant proteins, sequencing of RNA (RNA-Seq) was applied in our study as a powerful technique to identify any possible proteases expressed during the agroinfiltration process which might compromise recombinant protein production. RNA-Seq was conceived about 10 years ago and has become a preferred technology for transcriptome and gene analysis with a number of advantages.26,27 RNA-Seq is not dependent on sequence knowledge being available a priori and provides a direct measure of RNA abundance. The technology, although powerful, still has the problem of introducing a certain degree of bias due to the sequencing of pooled samples. Rigorous post-sequencing bioinformatics data analysis, as done in our study, is therefore required as well as a final validation of determined gene expression via alternative methods such as RT-qPCR (reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR). However, a problem faced in our study, when working with tobacco, was mismatches between gene identifiers and existing gene annotations rendering the annotation process an arduous and challenging task.

By performing RNA-seq analyses, we were able to obtain a transcriptomic profile for proteases in operation during the early stages of agroinfiltration. Members of the C1 and C13 cysteine protease families were more expressed in agroinfiltrated leaves. This result supports our original hypothesis that proteases and, in particular, cysteine proteases are expressed during agroinfiltration. This is consistent with previous findings that C1 proteases are specifically up-regulated in response to pathogenic microbes.19,28 Studies have also shown that C1 family RD21-like cysteine proteases, XM_009614860.1 in our study, are important components of plant immunity.29,30 These proteases are also induced in senescing leaves in conjunction with the induction of vacuolar processing enzymes (VPEs).31 Endogenous cysteine protease inhibitors might further be possible interaction partners of RD21-like proteases to prevent RD21 activity. Our previous finding of better stability of a recombinant protein (GOR) produced via agroinfiltration in tobacco leaves engineered with the rice cysteine proteases inhibitor OC-I supports the idea that RD21-like proteases might have been inhibited by OC-I expression in a transgenic tobacco leaf resulting in better GOR production.23

A further C1 cysteine protease (ALP; XM_00959-4290.1) with aleurain-like activity was found to be expressed 4-times more. Plant aleurain, first isolated from barley and localized in the vacuole, is an amino-peptidase with a number of similarities to animal cathepsin H. These similarities include heterogeneity of charge forms, position of the NH2-terminus of the mature protein, and a similar pH-activity profile.32 Several cleavage sites were found in this study for cathepsin H-like proteases in our model recombinant proteins possibly compromising their stability. N. tabacum contains cathepsin H-like proteases, such as NtCP-23 and NtCP1, with higher expression during natural senescence.23,33,34

The most prominent cysteine proteases induced in our study by agroinfiltration were 2 VPEs (NbVPE-1a & NbVPE-1b; AB181187.1 & AB181188.1). VPEs, so far, have not been extensively investigated in the context of degrading recombinant proteins. However, it is already known that prolonged incubation of anti-HIV antibodies 2F5 with high amounts of a VPE results in the formation of a 30-kDa degradation product implicating the involvement of VPEs in the degradation of this antibody.21 Such degradation might also be relevant for VP1 degradation in our study. VPE cleavage sites were identified in in silico cleavage analyses of VP1 and P1-polyprotein as well as that of GOR. Vegetative-type VPEs are generally expressed during senescence or the pathogen-induced hypersensitive response (HR).35 VPEs belong to the CD clan of cysteine proteases and within the clade they form part of the C13 family.36 VPEs contribute to the senescence process and PCD (programmed cell death) by participating in the collapse of the vacuole membrane with the release of proteases into the cell.37 VPEs are asparaginyl endopeptidases cleaving peptide bonds on the C-terminal side of asparagine (Asn) and aspartic (Asp) residues of pro-protein precursors to generate mature proteins.38 They occur along the secretory pathway and are located in the vacuole, except for a single cell wall specific VPE.15,39 Although VPEs have caspase-1 activity, they are structurally unrelated to caspases. Plants have evolved their own unique alternative regulated cellular suicide strategy that differs from animals with VPEs located in the vacuole as opposed to the cytosol.40

In our study, other possible protease candidates were also identified which might compromise recombinant protein production. This included the C1 cysteine proteases XM_009798142.1, a xylem cysteine peptidase 2 (XCP2) as well XM_009772991.1, a xylem bark cysteine peptidase 3 (XBCP3). Both proteases are involved in various cellular proteolytic processes. Their expression and induction was, however, not comparable to XM_009614860.1 (RD21) and any importance of these 2 proteases in recombinant protein degradation has yet to be determined. Also the expression of a metacaspase-1 (XM_009795875.1), involved in apoptosis, was identified in our study, as well as various aspartic, threonine and metallo-proteases. Serine and metallo-proteases have been already found in extracellular root and plant cell culture media. Lallemand et al. (2015) recently proposed that they are prime candidates in compromising protein stability. Since serine- or metallo-proteases were not strongly expressed in our study following agroinfiltration, their importance in compromising recombinant protein stability requires more detailed investigation.

Overall, our study has provided a more detailed insight of protease sensitivity of recombinant proteins, in particular, against cysteine proteases. Through, transcriptomic profiling and gene expression analysis, further evidence was provided that several cysteine proteases including proteases with RD21-like and aleurain-like activity as well as VPEs are upregulated during the early stages of agroinfiltration and might compromise recombinant protein production. However, the identified proteases still require more detailed analyses to confirm their direct involvement in recombinant protein degradation. Ultimately, characterization of identified proteases might also contribute toward establishing a protease library to be screened before any recombinant protein production is envisaged via agroinfiltration.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

N. benthamiana seeds were obtained from Dr. Ereck Chakauya (CSIR, Pretoria, South Africa) and were germinated in plastic trays in germination mix. Seedlings were grown at a 12/12 hours light/dark cycle with a day/night temperature of 26ºC/20ºC and 80% (v/v) relative humidity in a growth chamber (Sanyo, Bensenville, USA). Plants were grown for 12 weeks in order to obtain fully expanded leaves suitable for agroinfiltration.

VP1 expression and purification

Recombinant N-terminal His-tagged VP1 was expressed in E. coli M15 cells with bacteria grown in LB medium containing 100 µg mL−1 ampicillin, at 37°C up to a cell mass of 0.5 (OD600).41 Expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 5 h at 37°C and cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −20°C until use. All purification procedures were carried out as previously described with a purification column (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and elution with imidazole.42

Protein extraction

Whole leaf proteins were extracted in ice-cold Arakawa buffer containing 10 mM L-cysteine, 200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 400 mM Sucrose, 10 mM EDTA, 14 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 0.05% Tween-20.43 Total soluble protein (TSP) amount was determined with a commercial protein determination kit and standardized across samples within experiments (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

VP1 treatment

Varying amounts (0.5, 0.4, 0.3, and 0.2 µg) of either the cysteine protease, papain (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) or the serine protease, trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) were added to 44 µg of purified VP1 protein in 20 µL sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Tobacco extracts (230 µg total protein) were added to 15 µg of purified VP1 protein and incubated first for 2 hr at 25°C and then for 2 hr at 37°C.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Protein samples were boiled at 95°C for 5 min in a 4x SDS-containing reducing sample buffer. VP1 stability against proteases was fractionated on a 15% SDS-PAGE gel under reducing conditions with a Mini-PROTEAN® Electrophoresis System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).44 Western-blotting was carried out with a 0.45 µm Nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and a Mini-Trans-Blot electrophoretic transfer cell for protein transfer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at a constant current of 300 mA for 3 hr. For blotting, membranes were blocked overnight in 5% (w/v) skim milk solution in TBST buffer containing 100 mM Tris, 154 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.5. Incubation with the primary antibody (1:7000 dilution of the His-antiserum raised in rabbit) was done overnight in a 5% (w/v) skim milk-TBST solution. Incubation with the secondary antibody (1:10000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase; AbD Serotec, UK) was then done for 1 hr. Membranes were finally developed with the AP (Alkaline Phosphatase) Conjugate Substrate Kit as described in the manufacturers protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Protease activity measurement

Total soluble protein (TSP) from foliar extracts (36 µg) were used for measuring cathepsin L-like protease activity in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0 (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) containing 10 mM L-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and cathepsin H-like protease activity in a 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 6.0). Extracts were mixed and transferred into black, flat-bottom polysorp 96 well plates (Nunc, AEC Amersham) for measuring fluorescence. Before measuring fluorescence, 8 µM of the substrate Z-Phe-Arg-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin hydrochloride (Z-Phe-Arg-MCA, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for cathepsin L-like activity, or Arginine-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin hydrochloride (Arg-NMec HCl, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for cathepsin H-like activity, was added in a final volume of 100 µL. Activity was measured kinetically over a 10 min time period with 20 seconds (sec) of shaking before the first cycle. Fluorescence development was measured with a fluorometer (BMG FluoStar Galaxy, Germany) at 25°C with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 nm and 450 nm, respectively. Legumain activity in TSP (36 µg) was measured in a legumain assay buffer, pH 5.8, containing 1 mM DTT, 39.5 mM citric acid, 121 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 0.01% CHAPS (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Extracts were mixed and prepared as described above and protease activity was measured fluorometrically after addition of 1 mM of substrate Z-Ala-Ala-Asn-AMC (Z-AAN-AMC, Bachem, Germany) as described above for cathepsin L and H activity. A broad spectrum commercial inhibitor N-[N-(L-3-transcarboxyirane-2-carbonyl)-L-Leucyl]-agmatine (E-64, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) or 10 µM. purified oryzacystatin-I (OCI) (Department of Plant Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa) was used to inhibit cathepsin L-like and legumain protease activity. A commercial inhibitor N-a-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone hydrochloride (TLCK, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was used to inhibit cathepsin H-like protease activity at 20 µM.

In silico proteolytic cleavage analyses

Proteolytic cleavage assays were conducted in silico with CLC Main Workbench 6.6.1 (http://www.clcbio.com) based on various proteases substrate specificities and the Schechter and Berger (1967, 1968) subsite nomenclature.45-49 Protein structures and amino acid sequences were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) (www.rcsb.org).50 Structures obtained were: P1 – PDB ID: 1FOD,51 GOR – PDB ID: 3GRS,52 Papain – PDB ID: 9PAP53 and Trypsin – PDB ID: 1UTN.54 Substrate specificity profiling was determined using guidelines as previously described.47 Protein modeling was conducted between VP1 and papain as well as trypsin, by applying ZDOCK (http://zdock.umassmed.edu/).55,56 Both the unblocked and blocked settings were used on binding sites within the other P1-polyprotein chains (VP2, VP3 and VP4) when conducting the modeling. Blocking binding sites in the other chains were conducted to simulate an interaction with only VP1 and the respective proteases. Models were visualized in 3D-Mol Viewer (a component of Vector NTI 9.1.0, Invitrogen) and distances between interacting residues were measured using the measure distance tool. The setting structure was used as the color theme. VP2 – 4 were hidden from selections to highlight the interaction between VP1 and the protease. Distances were measured in the measure distance mode in Ångstroms (Å) between defined molecules in amino acids.

Agroinfiltration

Syringe agroinfiltration was used to infiltrate the tobacco leaf surface.7 Cultures were maintained in lysogeny broth (LB) medium supplemented with 50 µg mL−1 kanamycin and 50 µg mL−1 rifampicin. For agroinfiltration, bacteria were grown to the stable phase at 28°C to an OD600 of 1 and collected by centrifugation at 4000g. Bacterial pellets were re-suspended in MMA medium (10 mM 2-[N-morpholino] ethanesulfonic acid] (MES) buffer, pH 5.6, containing 100 µM acetosyringone and 10 mM MgCl2. For RNA-seq (RNA sequencing) analyses, the first fully-expanded leaves of the upper 4 individual leaves were infiltrated as previously described using a needle-less syringe with the vector pB+O1KP1-HT (gift from Prof George Lommonossoff; John Innes Center, Norwich, UK) containing the P1-polyprotein (P1) coding sequence (Fig. 1a) or with the pGK2 construct (Fig. 1b) containing the glutathione reductase (GOR) coding sequence.7,19 Leaves were also agroinfiltrated with A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404 (LBA) alone. Uninfiltrated leaf material (UN) and infiltration with MMA medium were applied as negative controls to avoid confounding effects due to experimental conditions. Infiltrated plants were kept in a growth cabinet (Sanyo, Bensenville, USA) for 24 h. Three biological (plant) replicates were used for each treatment allowing for statistical treatment of data. Plants were kept in an environmentally controlled growth room and watered daily. Four leaves per plant were harvested after 24 h, as source material for subsequent protein and RNA extraction. Leaf samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until protein or RNA extraction was carried out.

RNA extraction

RNA extraction on leaf tissue samples was carried out with the Trizol method by employing macro-dissection.57 Ribolock (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) was added to the final volume of RNA in a ratio of 1:10 (v/v). On-column DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) digests were performed with the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA samples were initially analyzed on a full-spectrum spectrophotometer Nanodrop® ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) and subsequently sent for RNA quality analyses on the Experion™ Automated Electrophoresis System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). After quantification, RNA samples from each sample were equivalently pooled for RNA-seq analyses. Biological replicates for each group were kept separate for RT-qPCR (reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR) analyses.

RNA-seq and mapping

A transcriptomic library was constructed from paired end reads of ∼90 bp in size which were generated from the HiSeq 2000 sequencing system (Illumina® sequencing, San Diego, USA) at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI Tech Solutions Co., Ltd, Hong Kong, China). Galaxy (Department of Bioinformatics, University of Pretoria), a platform for working with sequencing data, was applied to visualize, interpret, and conduct further analyses on the data generated.58-60 As part of the filtering process, reads with adaptors, unknown nucleotides larger than 5% and with low quality (more than 20% of the bases' qualities are less than 10 in a read) were removed (BGI Tech Solutions Co., Ltd, Hong Kong, China). The FastQC tool was applied to perform QC checks on the data (Supplementary Fig. 1). The FastQ groomer was then used to convert the data into a format amenable for subsequent interpretation.61 The draft assembly of the N. benthamiana genome was applied as a reference genome.2,3,62 With TopHat2 RNA-Seq reads were aligned to the tobacco genome available from the Solanaceae Genomics Network (SGN) at url (ftp://ftp.solgenomics.net/genomes/Nicotiana_benthamiana/).63,64 Tophat2 was carried out with a mean inner distance between mate pairs of 120 and a standard deviation of 30.

Transcript abundances and gene annotation

Cufflinks was applied performing bias correction and in default mode for all other parameters to assemble transcripts and estimate abundances.65 High-confidence transcripts were obtained from identified transcripts (i.e., transcripts with FPKM value in the case of cufflinks > 0) by filtering for a FPKM 95 % confidence interval lower boundary greater than zero and FPKM value ≥ 0.001. With MEROPS, Sol Genomics Network (http://solgenomics.net/organism/Nicotiana_benthamiana/genome), and TAIR databases, proteases were mined from data sets.2,3,62,66,67 Blast analyses against the draft genome of N. benthamiana were conducted with the BLASTN tool.2,3,62 Tracking IDs were obtained for transcripts of interest and applying the Log10 of FPKM expression data values and transcript abundances were established.68 Gene annotation was conducted using Blast2GO, TAIR as well as NCBI databases.67,69,70

RT-qPCR analyses

mRNA transcripts for 3 proteolytic candidate proteases (RD21, NbVPE1a and NbVPE1b) were assayed by RT-qPCR with a Bio-Rad CFX C1000™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). cDNA synthesis was done with the Promega GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Madison, Wisconsin, USA). RT-qPCR assays were carried out in accordance with the MIQE guidelines and optimized for annealing temperature and primer efficiency.71 Reactions contained 10 µM forward and reverse primer and 2.5 µL of cDNA template. Supplementary Table 1 provides information of primer sets used. No-template mixture controls were included in each 96-well plate. Thermocycling parameters included initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 39 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing and extension at the abovementioned ranges for 30 sec, denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec. Melt curve analyses were performed thereafter from 65°C to 95°C with 0.5 increments. Fold changes in gene expression were determined with the Livak method.72 For comparative purposes, relative gene expression was defined with the value of 1 in control plants.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant changes in gene expression between control and experimental groups were determined using ANOVA: single/2-factor with replication (p-value < 0.05) applying Microsoft Excel software 2010 version 14 (Microsoft Corporation). Bonferroni corrected post-hoc t-tests (p-value < 0.05) were subsequently performed.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Yong Suk Jang, Professor Moon Sik Yang and Dr. Tae Geum Kim for providing us with the VP1 gene and Dr. Huy for assisting with the VP1 purification, Professor George Lomonossoff for providing the P1 construct, and Professor Christine Foyer for providing the GOR construct. We also thank Dr. Francois Maree (Ondersterpoort Veterinary campus, University of Pretoria, South Africa) who kindly provided the Anti-FMDV polyclonal antiserum and Professor Dominique Michaud for assisting us to establish the agroinfiltration technique.

Funding

Our research was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Genomics Research Institute (GRI), South Africa as well as NRF incentive funding to Karl Kunert and a NRF bursary to Priyen Pillay.

Notes on contributors

PP and KJK conceptualised and designed the experiment. PP conducted the experiments. BJV financially supported the project and provided analytical tools and scientific intellectual input in data interpretation. MEM helped in running enzymatic assays. CAC and SGVW helped in analyzing the RNAseq data and manuscript reading. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- [1].Zhang Y, Li D, Jin X, Huang Z. Fighting Ebola with ZMapp: spotlight on plant-made antibody. Sci China Life Sci 2014; 57:987-8; PMID:25218825; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11427-014-4746-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bombarely A, Rosli HG, Vrebalov J, Moffett P, Mueller LA, Martin GB. A draft genome sequence of Nicotiana benthamiana to enhance molecular plant-microbe biology research. Mol Plant Microbe In 2012; 25:1523-30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0148-TA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Goodin MM, Zaitlin D, Naidu RA, Lommel SA. Nicotiana benthamiana: Its history and future as a model for plant-pathogen interactions. Mol Plant Microbe In 2008; 21:1015-26; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1094/MPMI-21-8-1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Faino L, de Jonge R, Thomma BP. The transcriptome of Verticillium dahliae-infected Nicotiana benthamiana determined by deep RNA sequencing. Plant Signal Behav 2012; 7:1065; PMID:22899084; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/psb.21014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Abiri R, Valdiani A, Maziah M, Shaharuddin NA, Sahebi M, Yusof Zy, Atabaki N, Talei D. A critical review of the concept of transgenic plants: insights into pharmaceutical biotechnology and molecular farming. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2015; 18:21-42; PMID:25944541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wagner B, Fuchs H, Adhami F, Ma Y, Scheiner O, Breiteneder H. Plant virus expression systems for transient production of recombinant allergens in Nicotiana bentha-miana. Methods 2004; 32:227-34; PMID:14962756; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].D'Aoust MA, Lavoie PO, Belles-Isles J, Bechtold N, Martel M, Vézina LP. Transient expression of antibodies in plants using syringe agroinfiltration. Recombinant Proteins From Plants 2009; 483:41-50; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-59745-407-0_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Van der Hoorn RA, Laurent F, Roth R, De Wit PJ. Agroinfiltration is a versatile tool that facilitates comparative analyses of Avr9/Cf-9-Induced and Avr4/Cf-4-induced necrosis. Phytopathol 2000; 13:439-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Outchkourov NS, Rogelj B, Strukelj B, Jongsma MA. Expression of sea anemone equistatin in potato. Effects of plant proteases on heterologous protein production. Plant Physiol 2003; 133:379-90; PMID:12970503; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.102.017293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Donini M, Lombardi R, Lonoce C, Di Carli M, Marusic C, Morea V, Di Micco P. Antibody proteolysis: a common picture emerging from plants. Bioengineered 2015; 6(5):299-302; PMID:26186119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/21655979.2015.1067740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miletic S, Simpson DJ, Szymanski CM, Deyholos MK, Menassa R. A plant-produced bacteriophage tailspike protein for the control of Salmonella. Front Plant Sci 2015; 6:1-9; PMID:25653664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Faye L, Boulaflous A, Benchabane M, Gomord V, Michaud D. Protein modifications in the plant secretory pathway: Current status and practical implications in molecular pharming. Vaccine 2005; 23:1770-8; PMID:15734039; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Castilho A, Windwarder M, Gattinger P, Mach L, Strasser R, Altmann F, Steinkellner H. Proteolytic and N-Glycan processing of Human α1-Antitrypsin expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Physiol 2014; 166:1839-51; PMID:25355867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.114.250720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Delannoy M, Alves G, Vertommen D, Ma J, Boutry M, Navarre C. Identification of peptidases in Nicotiana tabacum leaf intercellular fluid. Proteomics 2008; 8:2285-98; PMID:18446799; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/pmic.2007-00507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goulet C, Khalf M, Sainsbury F, D'Aoust MA, Michaud D. A protease activity-depleted environment for heterologous proteins migrating towards the leaf cell apoplast. Plant Biotechnol J 2012; 10:83-94; PMID:21895943; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Benchabane M, Goulet C, Rivard D, Faye L, Gomord V, Michaud D. Preventing unintended proteolysis in plant protein biofactories. Plant Biotechnol J 2008; 6:633-48; PMID:18452504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00344.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Roberts IN, Caputo C, Criado MV, Funk C. Senescence-associated proteases in plants. Physiol Plant 2012; 145:130-39; PMID:22242903; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goulet C, Goulet C, Goulet MC, Michaud D. 2-DE proteome maps for the leaf apoplast of Nicotiana benthamiana. Proteomics 2010; 10:2536-44; PMID:20422621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/pmic.200900382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Robert S, Khalf M, Goulet MC, D'Aoust MA, Sainsbury F, Michaud D. Protection of recombinant mammalian antibodies from development-dependent proteolysis in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. PloS One 2013; 8:1-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lallemand J, Bouché F, Desiron C, Stautemas J, De Lemos Esteves F, Périlleux C, Tocquin P. Extracellular peptidase hunting for improvement of protein production in plant cells and roots. Front Plant Sci 2015; 6:1-10; PMID:25653664; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fpls.2015.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Niemer M, Mehofer U, Torres Acosta JA, Verdianz M, Henkel T, Loos A, Strasser R, Maresch D, Rademacher T, Steinkellner H, et al.. The human anti-HIV antibodies 2F5, 2G12, and PG9 differ in their susceptibility to proteolytic degradation: Down-regulation of endogenous serine and cysteine proteinase activities could improve antibody production in plant-based expression platforms. Biotechnol J 2014; 9:493-500; PMID:24478053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/biot.201300207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Veena Jiang H, Doerge R, Gelvin SB. Transfer of T-DNA and Vir proteins to plant cells by Agrobacterium tumefaciens induces expression of host genes involved in mediating transformation and suppresses host defense gene expression. Plant J 2003; 35:219-36; PMID:12848827; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pillay P, Kibido T, Plessis M, Vyver C, Beyene G, Vorster BJ, Kunert KJ, Schlüter U. Use of transgenic Oryzacystatin-I-expressing plants enhances recombinant protein production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2012; 168:1608-20; PMID:22965305; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12010-012-9882-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Butt TR, Edavettal SC, Hall JP, Mattern MR. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Express Purif 2005; 43:1-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pan L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang B, Wang W, Fang Y, Jiang S, Lv J, Wang W, Sun Y, et al.. Foliar extracts from transgenic tomato plants expressing the structural polyprotein, P1-2A, and protease, 3C, from foot-and-mouth disease virus elicit a protective response in guinea pigs. Vet Immunol Immunop 2008; 121:83-90; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat methods 2008; 5:621-8; PMID:18516045; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10:57-63; PMID:19015660; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gilroy EM, Hein I, Van Der Hoorn R, Boevink PC, Venter E, McLellan H, Kaffarnik F, Hrubikova K, Shaw J, Holeva M, et al.. Involvement of cathepsin B in the plant disease resistance hypersensitive response. Plant J 2007; 52:1-13; PMID:17697096; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gu C, Shabab M, Strasser R, Wolters PJ, Shindo T, Niemer M, Kaschani F, Mach L, van der Hoorn RA. Post-translational regulation and trafficking of the granulin-containing protease RD21 of Arabidopsis thaliana. PloS One 2012; 7:1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shindo T, Misas-Villamil JC, Hörger AC, Song J, van der Hoorn RA. A role in immunity for Arabidopsis cysteine protease RD21, the ortholog of the tomato immune protease C14. PloS One 2012; 7:1-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0029317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kinoshita T, Yamada K, Hiraiwa N, Kondo M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme is up-regulated in the lytic vacuoles of vegetative tissues during senescence and under various stressed conditions. Plant J 1999; 19:43-53; PMID:10417725; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Holwerda BC, Rogers JC. Purification and characterization of aleurain A plant thiol protease functionally homologous to mammalian cathepsin H. Plant Physiol 1992; 99:848-55; PMID:16669011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.99.3.848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ueda T, Seo S, Ohashi Y, Hashimoto J. Circadian and senescence-enhanced expression of a tobacco cysteine protease gene. Plant Mol Biol 2000; 44:649-57; PMID:11198425; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1026546004942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Beyene G, Foyer CH, Kunert KJ. Two new cysteine proteinases with specific expression patterns in mature and senescent tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) leaves. J Exp Bot 2006; 57:1431-43; PMID:16551685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jxb/erj123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yamada K, Shimada T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. A VPE family supporting various vacuolar functions in plants. Physiol Plant 2005; 123:369-75; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00464.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mosolov V, Valueva T. Participation of proteolytic enzymes in the interaction of plants with phytopathogenic microorganisms. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2006; 71:838-45; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1134/S0006297906080037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hara-Nishimura I, Hatsugai N, Nakaune S, Kuroyanagi M, Nishimura M. Vacuolar processing enzyme: an executor of plant cell death. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2005; 8:404-8; PMID:15939660; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hara-Nishimura I, Hatsugai N, Nakaune S, Kuroyanagi M, Nishimura M. Vacuolar processing enzyme: an executor of plant cell death. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2005; 8:404-8; PMID:15939660; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Müntz K, Blattner FR, Shutov AD. Legumains-a family of asparagine-specific cysteine endopeptidases involved in propolypeptide processing and protein breakdown in plants. J Plant Physiol 2002; 159:1281-93; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1078/0176-1617-00853 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hatsugai N, Kuroyanagi M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. A cellular suicide strategy of plants: vacuole-mediated cell death. Apoptosis 2006; 11:905-11; PMID:16547592; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10495-006-6601-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pillay P. Expression of the VP1 antigen from foot-and-mouth disease virus in a bacterial and plant-based expression system Plant Sciences. South Africa: University of Pretoria, 2012:149 [Google Scholar]

- [42].Crowe JH. The QIA expressionist. Chatsworth, CA: 1992 [Google Scholar]

- [43].Arakawa T, Chong DK, Merritt JL, Langridge WH. Expression of cholera toxin B subunit oligomers in transgenic potato plants. Transgenic Res 1997; 6:403-13; PMID:9423288; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1018487401810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970; 227:680-5; PMID:5432063; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem Bioph Res Co 1967; 27:157-62; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-291X(67)80055-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Schechter I, Berger A. On the active site of proteases. III. Mapping the active site of papain; specific peptide inhibitors of papain. Biochem Bioph Res Co 1968; 32:898-902; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0006-291X(68)90326-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Choe Y, Leonetti F, Greenbaum DC, Lecaille F, Bogyo M, Brömme D, Ellman JA, Craik CS. Substrate profiling of cysteine proteases using a combinatorial peptide library identifies functionally unique specificities. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:12824-32; PMID:16520377; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M513331200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Guncar G, Podobnik M, Pungercar J, Strukelj B, Turk V, Turk D. Crystal structure of porcine cathepsin H determined at 2.1 Å resolution: location of the mini-chain C-terminal carboxyl group defines cathepsin H aminopeptidase function. Structure 1998; 6:51-61; PMID:9493267; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00007-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mathieu MA, Bogyo M, Caffrey CR, Choe Y, Lee J, Chapman H, Sajid M, Craik CS, McKerrow JH. Substrate specificity of schistosome versus human legumain determined by P1-P3 peptide libraries. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2002; 121:99-105; PMID:11985866; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00026-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat T, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28:235-42; PMID:10592235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/28.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Logan D, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Blakemore W, Curry S, Jackson T, King A, Lea S, Lewis R, Newman J, Parry N, et al.. Structure of a major immunogenic site on foot-and-mouth disease virus. Nature 1993; 362:566-8; PMID:8385272; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/362566a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Karplus PA, Schulz GE. Refined structure of glutathione reductase at 1.54 Å resolution. J Mol Biol 1987; 195:701-29; PMID:3656429; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90191-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kamphuis IG, Kalk K, Swarte M, Drenth J. Structure of papain refined at 1.65 Å resolution. J Mol Biol 1984; 179:233-56; PMID:6502713; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90467-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Leiros HK, Brandsdal BO, Andersen OA, Os V, Leiros I, Helland R, Otlewski J, Willassen NP, Smalås AO. Trypsin specificity as elucidated by LIE calculations, X-ray structures, and association constant measurements. Protein Sci 2004; 13:1056-70; PMID:15044735; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1110/ps.03498604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pierce BG, Wiehe K, Hwang H, Kim B-H, Vreven T, Weng Z. ZDOCK server: interactive docking prediction of protein-protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:1771-3; PMID:24532726; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chen R, Li L, Weng Z. ZDOCK: An initial-stage protein-docking algorithm. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinf 2003; 52:80-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.10389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].MacRae E. Extraction of plant RNA. Methods Mol Biol. Protocols for Nucleic Acid Analysis by Nonradioactive Probes: Springer 2007; 353:15-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol 2010; 11:1-13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, Burhans R, Elnitski L, Shah P, Zhang Y, Blankenberg D, Albert I, Taylor J, et al.. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res 2005; 15:1451-5; PMID:16169926; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.4086505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Blankenberg D, Kuster GV, Coraor N, Ananda G, Lazarus R, Mangan M, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010 Jan; Chapter 19:Unit 19.10.1-21. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/0471142727.mb1910s89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Blankenberg D, Gordon A, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, Taylor J, Nekrutenko A. Manipulation of FASTQ data with Galaxy. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:1783-5; PMID:20562416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Knapp S, Chase MW, Clarkson JJ. Nomenclatural changes and a new sectional classification in Nicotiana (Solanaceae). Taxon 2004; 53:73-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2307/4135490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bombarely A, Menda N, Tecle IY, Buels RM, Strickler S, Fischer-York T, Pujar A, Leto J, Gosselin J, Mueller LA. The Sol Genomics Network (solgenomics. net): growing tomatoes using Perl. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39:D1149-D55; PMID:20935049; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkq866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 2013; 14:1-13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnol 2010; 28:511-5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Rawlings ND, Waller M, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 42:D503-D9; PMID:24157837; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lamesch P, Berardini TZ, Li D, Swarbreck D, Wilks C, Sasidharan R, Muller R, Dreher K, Alexander DL, Garcia-Hernandez M, et al.. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:D1202-D10; PMID:22140109; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkr1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression pat-terns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95:14863-8; PMID:9843981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:3674-6; PMID:16081474; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:3389-402; PMID:9254694; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, et al.. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 2009; 55:611-22; PMID:19246619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001; 25:402-8; PMID:11846609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.