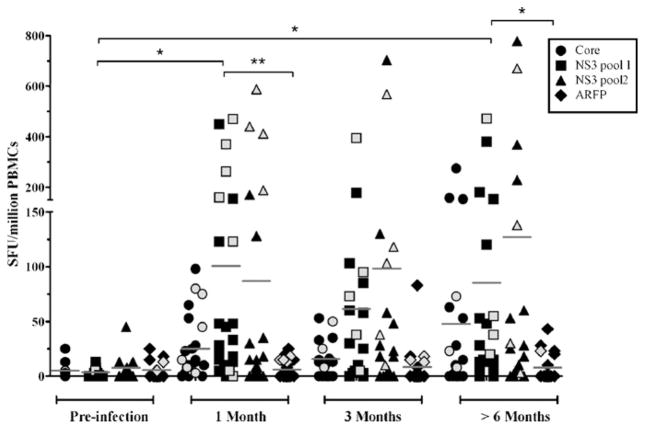

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) alternate reading frame protein (ARFP) is produced as a result of alternate translational decoding of the core protein gene.1,2 ARFP induces production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and fibrogenic chemokines, suggesting a role in hepatic injury.3–10 ARFP has been reported to co-localize in the mitochondria and differential mitochondrial targeting may influence hepatocyte apoptosis and viral clearance.11 However, biological functions of ARFP are difficult to dissociate from those of RNA structures located within the core-ARFP coding region.12 Humoral and cell-mediated ARFP-specific immune responses are present during chronic HCV infection, confirming its expression in vivo.13–15 Because it is located in the 5′ region of HCV and its expression is presumably independent of viral and host proteases, ARFP could be expressed early following infection.16 This is a key point because immunodominance and epitope hierarchy in antiviral responses are strongly influenced by the timing of viral gene expression.17 Spontaneous resolution of HCV infection occurs in 20–30% of cases and is associated with broad, multi-specific and sustained CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses.18–21 However, the kinetics of ARFP-specific cell-mediated immunity and its implication in HCV clearance remain unclear. To address this question, IFN-γ ELISpot was used to examine ARFP-specific cell-mediated immune responses in a group of subjects with acute HCV infection (n = 30) who either spontaneously cleared the virus (n = 8) or progressed to chronic infection (n = 22) recruited through the Montreal Acute Hep C cohort.22 Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected before infection, during the acute phase (1–3 months), and following resolution or establishment of chronic infection (>6 months) were used. ELISpot assays were performed as previously described23 using antigenic peptides, 15–19 amino acids in length with 11–12 residues overlap, divided in 4 pools of 25–46 peptides corresponding to HCV core, NS3 (1027–1339), NS3 (1340–1658) and ARFP proteins (BEI Resources Repository, Manassas, VA). Consistent with previous reports,18–21 NS3-specific T cells were detected at high frequency in the majority of study subjects, and were not significantly different between spontaneous resolvers and chronics (Fig. 1 and data not shown). In contrast, ARFP-specific T cell responses were not observed in any of the study subjects, irrespective of the outcome of acute HCV infection and in spite of the fact that all patients exhibited detectable levels of ARFP-specific antibodies in serum (data not shown). These results strongly suggest that ARFP-specific cell-mediated immune responses that involve IFN-γ production either develop late or are of low magnitude during acute HCV infection, and that they play no major role in spontaneous viral clearance. It was recently reported that ARFP expression can be suppressed by core protein,24 and that ARFP binds the proteasome α3 subunit and is degraded by an ubiquitin-independent pathway.25 These results confirm that ARFP is short-lived and are consistent with the low frequency of ARFP-specific T cells observed in our study group. Overall, data presented herein indicate that resolution of acute HCV infection is not associated with the presence of significant ARFP-specific cell-mediated immune responses. Interestingly, this also suggests that enhancement of these responses through immunization against ARFP could potentially lead to heightened rates of spontaneous viral clearance.

Fig. 1.

HCV-specific cell-mediated immune responses in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from subjects acutely infected with HCV. IFN-γ production was quantified in individuals acutely infected with HCV followed by spontaneous viral clearance (gray symbols) or persistent infection (black symbols) using ELISpot following in vitro stimulation with pooled overlapping peptide panels representing HCV core protein (26 peptides), NS3 pool 1 (residues 1027–1339) (45 peptides), NS3 pool 2 (residues 1340–1658) (46 peptides), and ARFP (25 peptides). 2 × 105 cryopreserved PBMCs were stimulated in duplicates with HCV peptide pools at a final concentration of 3 μg/ml of each peptide for 36 h as previously described.23 Specific spot forming units (SFU) were calculated as (mean number of spots in test wells-mean number of spots in media control wells) and normalized to SFU/106 PBMCs. A response was scored positive if greater than 50 SFU/106 PBMCs. Peptides were based on the sequence of HCV-1a (H77) or HCV-3a (K3a/650), depending on the infecting viral genotype. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskall–Wallis test with Dunn’s post test (GraphPad Prism 4, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) (MOP-74524) to NHS, CIHR-Health Canada Research Initiative on Hepatitis C (EOP-41537) and UNIVALOR SEC to HS and the FRSQ-AIDS and Infectious Disease Network (SIDA-MI). J. Bruneau holds a senior clinical research award from FRSQ. N.H. Shoukry holds a joint New Investigator Award from the Canadian Foundation for Infectious Diseases and CIHR.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Walewski JL, Keller TR, Stump DD, Branch AD. Evidence for a new hepatitis C virus antigen encoded in an overlapping reading frame. RNA. 2001;7:710–21. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Z, Choi J, Yen TS, et al. Synthesis of a novel hepatitis C virus protein by ribosomal frameshift. EMBO J. 2001;20:3840–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam SS, Nakamura T, Naganuma A, et al. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies in cancerous and noncancerous hepatic lesions: the core protein-encoding region. Acta Med Okayama. 2002;56:141–7. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basu A, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Functional properties of a 16 kDa protein translated from an alternative open reading frame of the core-encoding genomic region of hepatitis C virus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2299–306. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen M, Bachmatov L, Ben-Ari Z, Rotman Y, Tur-Kaspa R, Zemel R. Development of specific antibodies to an ARF protein in treated patients with chronic HCV infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2427–32. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorucci M, Boulant S, Fournillier A, et al. Expression of the alternative reading frame protein of Hepatitis C virus induces cytokines involved in hepatic injuries. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1149–62. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma HC, Lin TW, Li H, et al. Hepatitis C virus ARFP/F protein interacts with cellular MM-1 protein and enhances the gene trans-activation activity of c-Myc. J Biomed Sci. 2008;15:417–25. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogata S, Nagano-Fujii M, Ku Y, Yoon S, Hotta H. Comparative sequence analysis of the core protein and its frameshift product, the F protein, of hepatitis C virus subtype 1b strains obtained from patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3625–30. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3625-3630.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsao ML, Chao CH, Yeh CT. Interaction of hepatitis C virus F protein with prefoldin 2 perturbs tubulin cytoskeleton organization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh CT, Lo SY, Dai DI, Tang JH, Chu CM, Liaw YF. Amino acid substitutions in codons 9–11 of hepatitis C virus core protein lead to the synthesis of a short core protein product. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:182–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratinier M, Boulant S, Crussard S, McLauchlan J, Lavergne JP. Subcellular localizations of the hepatitis C virus alternate reading frame proteins. Virus Res. 2009;139:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMullan LK, Grakoui A, Evans MJ, et al. Evidence for a functional RNA element in the hepatitis C virus core gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611267104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bain C, Parroche P, Lavergne JP, et al. Memory T-cell-mediated immune responses specific to an alternative core protein in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:10460–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10460-10469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komurian-Pradel F, Rajoharison A, Berland JL, et al. Antigenic relevance of F protein in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;40:900–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troesch M, Jalbert E, Canobio S, et al. Characterization of humoral and cell-mediated immune responses directed against hepatitis C virus F protein in subjects co-infected with hepatitis C virus and HIV-1. AIDS. 2005;19:775–84. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168971.57681.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walewski JL, Gutierrez JA, Branch-Elliman W, et al. Mutation Master: profiles of substitutions in hepatitis C virus RNA of the core, alternate reading frame, and NS2 coding regions. RNA. 2002;8:557–71. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202029023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yewdell JW, Del Val M. Immunodominance in TCD8+ responses to viruses: cell biology, cellular immunology, and mathematical models. Immunity. 2004;21:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauer GM, Barnes E, Lucas M, et al. High resolution analysis of cellular immune responses in resolved and persistent hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:924–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulze zur Wiesch J, Lauer GM, Day CL, et al. Broad repertoire of the CD4+ Th cell response in spontaneously controlled hepatitis C virus infection includes dominant and highly promiscuous epitopes. J Immunol. 2005;175:3603–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoukry NH, Cawthon AG, Walker CM. Cell-mediated immunity and the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:391–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyk-Pearson S, Tester IA, Lezotte D, Sasaki AW, Lewinsohn DM, Rosen HR. Differential antigenic hierarchy associated with spontaneous recovery from hepatitis C virus infection: implications for vaccine design. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:454–63. doi: 10.1086/505714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox AL, Page K, Bruneau J, et al. Rare birds in North America: acute hepatitis C cohorts. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:26–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvarez-Lajonchere L, Shoukry NH, Gra B, et al. Immunogenicity of CIGB-230, a therapeutic DNA vaccine preparation, in HCV-chronically infected individuals in a Phase I clinical trial. J Viral Hepatol. 2009;16:156–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf M, Dimitrova M, Baumert TF, Schuster C. The major form of hepatitis C virus alternate reading frame protein is suppressed by core protein expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3054–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuksek K, Chen WL, Chien D, Ou JH. Ubiquitin-independent degradation of hepatitis C virus F protein. J Virol. 2009;83:612–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00832-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]