Abstract

The high energy demand of the brain renders it sensitive to changes in energy fuel supply and mitochondrial function. Deficits in glucose availability and mitochondrial function are well-known hallmarks of brain aging and are particularly accentuated in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. As important cellular sources of H2O2, mitochondrial dysfunction is usually associated with altered redox status. Bioenergetic deficits and chronic oxidative stress are both major contributors to cognitive decline associated with brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroinflammatory changes, including microglial activation and production of inflammatory cytokines, are observed in neurodegenerative diseases and normal aging. The bioenergetic hypothesis advocates for sequential events from metabolic deficits to propagation of neuronal dysfunction, to aging, and to neurodegeneration, while the inflammatory hypothesis supports microglia activation as the driving force for neuroinflammation. Nevertheless, growing evidence suggests that these diverse mechanisms have redox dysregulation as a common denominator and connector. An independent view of the mechanisms underlying brain aging and neurodegeneration is being replaced by one that entails multiple mechanisms coordinating and interacting with each other. This review focuses on the alterations in energy metabolism and inflammatory responses and their connection via redox regulation in normal brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Interactions of these systems is reviewed based on basic research and clinical studies.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Glucose Metabolism, Redox Control, Inflammation, Brain aging, Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

The aging brain reveals a plethora of correlated processes that contribute to its senescence, yet to be fully understood on a molecular level. Age-related cognitive decline is one of the major risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other prevalent neurodegenerative disorders [1]. Neurons are capable of surviving for more than a hundred years and staying functionally competent, but aging is their biggest adversary. Bioenergetic deficits, oxidized redox environment, and low-levels of chronic inflammation are major contributors to the cognitive decline associated with brain aging and neurodegenerative disorders like AD.

The brain utilizes ~25% of the total body glucose [2], and the majority of which is used to transduce energy through glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to support synaptic transmission. Aging induces changes in both glucose availability and the mitochondria energy-transducing capacity, including decline in neuronal glucose uptake, decrease of electron transport chain activity, and increase in oxidant production. Post-mortem tissues of AD patients exhibit disruptions of mitochondrial functions in the form of a dysfunctional tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), compromised electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation, as well as altered mitochondrial morphology [3]. The ‘mitochondrial cascade hypothesis’ proposes that in late-onset sporadic AD, the genetic makeup of a person’s electron transport train sets the basis for oxidant production and the tone for oxidative damage, which drives the progression of other pathologies characteristic of AD [4].

Insulin and IGF-1 signaling (IIS) play critical roles in regulating and maintaining brain metabolic and cognitive function [5]. Preserved insulin sensitivity, low insulin levels, and a state of reduced flux through the IIS represent key metabolic features of a human longevity phenotype [6, 7]. Insulin signaling regulates mitochondrial function and its impairment causes abnormalities in mitochondrial function and biogenesis. On the other hand, controlled H2O2 production by mitochondria serves as a second messenger that enhances insulin sensitivity [8], while excessive levels of H2O2 activate stress-sensitive kinases (e.g. JNK and IKK), and lead to insulin resistance, and ultimately the bioenergetic deficits observed in the aging brain [9].

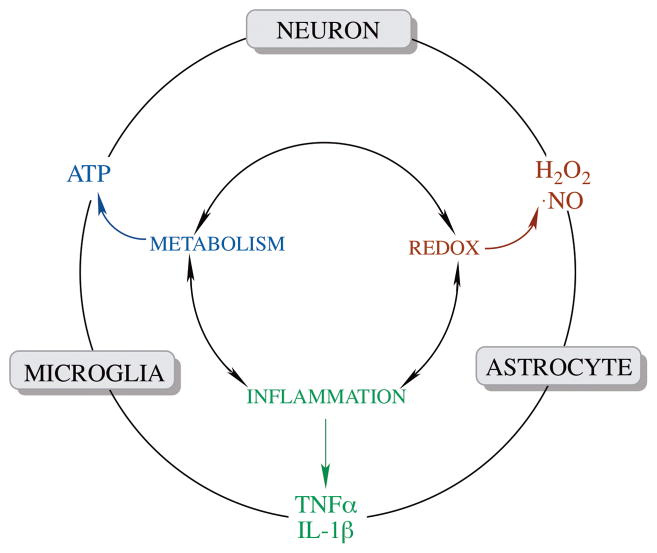

To add insult to injury, inflammatory processes are being associated with alterations in cellular metabolism [10, 11]. The activation of different types of brain immune cells such as microglia and astrocytes is one of the fundamental events in neuroinflammation [12]. Changes in the activation profile of microglia with age and increased release of inflammatory cytokines are hypothesized to induce development of insulin resistance [10, 11]. Amplification of the microglia-driven inflammatory responses by astrocytes generates neurotoxic factors leading to neurodegeneration [13]. A shift from a neurotrophic to neurotoxic phenotype in aging astrocytes thus denies neurons of essential energy substrates and neuro-protective mechanisms [14]. The activation of neuroinflammation is largely redox mediated, both at the molecular level in terms of redox sensitivity of key inflammatory components such as NFκB and inflammasomes, and at the cellular level where astrocytes transmit inflammatory signal to neurons via oxidants such as H2O2. The chronic inflammatory microenvironment, combined with a dysfunctional metabolic system is hypothesized to lead to neurodegeneration.

This review summarizes our current understanding of the relationship among metabolic, redox, and inflammatory changes in the brain as a function of age, and how these pathways converge and contribute to physiological and pathological changes occurring in normal aging- and Alzheimer’s brains.

2. Energy Metabolism in Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

Neuronal glucose metabolism includes (1) mechanisms that control brain glucose uptake, such as insulin and the insulin signaling pathways (Fig. 1); (2) glucose transporter (GLUT)-dependent brain glucose uptake and the glycolytic pathway (Fig. 2), and (3) entry of glycolytic endpoints into mitochondria that are further metabolized in the TCA cycle and generate ATP through oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 3). Because most of the neuronal energy-transducing pathways occur in mitochondria, it is important to consider that mitochondrial H2O2 participates in the regulation of redox-sensitive signaling, such as insulin/IGF1 (IIS) signaling, JNK signaling, and AMPK signaling. Mitochondria also receive and respond to cytosolic signaling, by which their metabolic and redox functions are modulated [15]. Overall, several signaling pathways and their second messengers, metabolites, transporters, receptors, and enzymes work in tandem with mitochondria to ensure adequate fuel supply and energy conservation to support neuronal function. As outlined in an earlier review [16], mitochondrion-centered hypometabolism is a key feature of brain aging and AD that is manifested by altered insulin signaling, decreased neuronal glucose uptake, changes in glucose receptors, and changes in the metabolic phenotype of astrocytes.

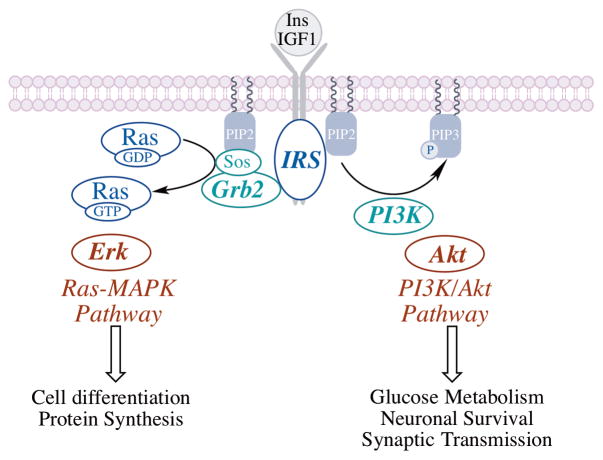

Fig. 1. Insulin/IGF1 signaling (IIS) is primarily orchestrated through insulin and IGF1 and the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways.

Binding of the ligand to insulin receptor or IGF1 receptor activates the insulin receptor substrate (IRS). Binding of PI3K to the phosphorylated IRS activates the PI3K/Akt signaling network, whereas recruitment of Grb2 to the IRS results in Sos-mediated activation of the Ras-MAPK pathway. The PI3K/Akt pathway effects changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and modulates glucose uptake, whereas the Ras-MAPK pathway is involved in cell growth and differentiation and protein synthesis.

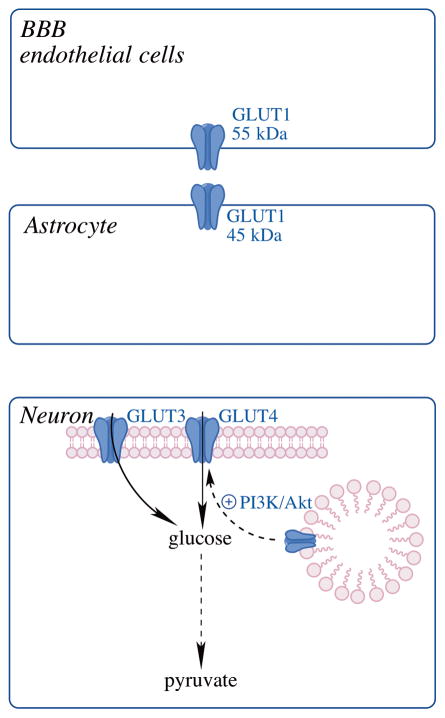

Fig. 2. Glucose transporters (GLUTs) in the brain.

GLUT1 (55kDa) is expressed in endothelial cells of the BBB; GLUT1 (45kDa)-mediated transport of glucose into astrocytes; glucose uptake into neurons via neuronal GLUTs, GLUT3 and the insulin-sensitive GLUT4.

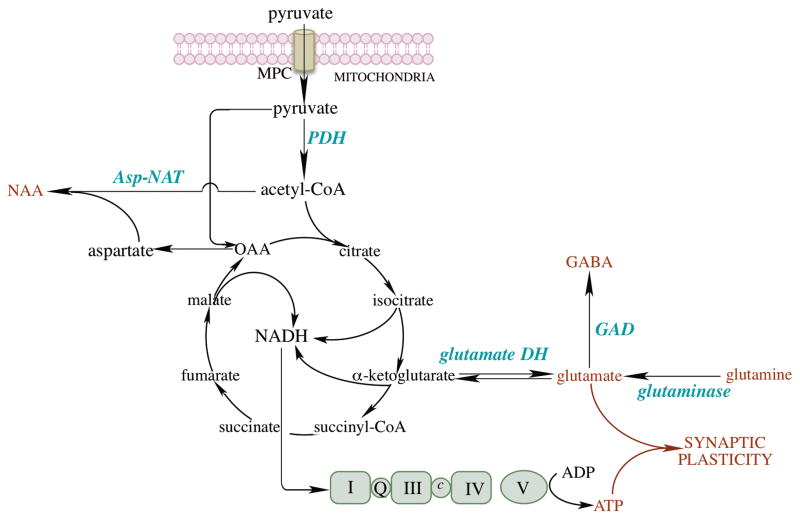

Fig. 3. Mitochondrial energy metabolism in brain.

Pyruvate imported by the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) is converted to acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle to generate NADH, the reducing equivalents of which flow through the respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. ATP generated by oxidative phosphorylation together with glutamate and GABA are critical for synaptic plasticity in brain. Glutamate is primarily generated from (a) α-ketoglutarate by glutamate dehydrogenase and (b) astrocyte-originated glutamine by glutaminase. GABA is produced by glutamate decarboxylase from glutamate. Acetyl-CoA is also a co-substrate for the synthesis of N-acetylaspartate (NAA) by aspartate N-acetyltransferase (Asp-NAT). Aspartate generated from oxaloacetate (coupled to the conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate) is critical in cell proliferation.

2.1. Insulin/IGF1 signaling (IIS) in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease

Insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling (IIS) is primarily orchestrated through insulin and IGF1, and the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways (Fig. 1). Following binding of the ligand to the insulin receptor, the activated signaling networks can be viewed in terms of critical nodes encompassed by the insulin receptor substrate (IRS), PI3K, and Akt [17]. Binding of PI3K to the phosphorylated IRS activates the PI3K/Akt signaling network, whereas recruitment of Grb2 to the IRS results in Sos-mediated activation of the Ras-MAPK pathway. The PI3K/Akt pathway effects changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and modulates glucose uptake, whereas the Ras-MAPK pathway is involved in cell growth, cell differentiation and protein synthesis. Optimal IIS has been suggested to maximize life span and also control metabolic requirements for an energy-demanding organ such as brain [18]. The balance between of IIS- and JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) signaling is crucial, for both elicit profound changes in mitochondrial function [19, 20]. Insulin resistance is usually accompanied by compromised mitochondrial function [21].

The physiological relevance of insulin in the brain has been increasingly recognized. The central nervous system was not considered to be an insulin-dependent tissue until the detection of insulin in brain [22]. In brain, the PI3K-Akt pathway is involved in glucose uptake, neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity [23, 24]. Conditional knockout of neuronal insulin receptors resulted in mice to be overweight, insulin resistant, and glucose intolerant [25].

IIS is also involved in the regulation of longevity. Early studies in C. elegans revealed that mutations of insulin receptor DAF-2 [26] or the PI3K AGE-1 [27] extended lifespan by more than 100%. Later studies showed that mutation of the insulin receptor in adipose tissue was able to extend mouse lifespan by 18% [28]; similarly, brain-specific IRS2 knockout in mice led to ~18% extension of lifespan [29]. Conversely, insulin resistance is implicated in many adverse aging phenotypes and age-related conditions, which make the enhancement of insulin signaling also an anti-aging intervention. This paradox can perhaps be explained by the several orders of complexity in mammalian physiology and the recognition of insulin signaling being important in events beyond the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Moreover, genetic modifications to the entire IIS may have significantly different effects compared to insulin resistance, where only specific functions of the insulin pathway are impaired [23, 30]. It has also been suggested that each organism has an optimal level of IIS that maximizes lifespan and regulates metabolic requirements [18]. The notion of optimal IIS also seems consistent with the results showing regulation of lifespan by caloric restriction: progressive reductions in calorie intake promoted lifespan until the optimal IIS was reached, after which, additional reductions in calorie intake caused starvation and shortening of lifespan [31].

Brain aging is associated with a reduced IIS pathway entailing inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling in rats [32]. Interestingly, a high-fat diet that led to hepatic insulin resistance was able to induce impairment of the long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 region of mouse hippocampi, which suggests the involvement of systemic insulin resistance in regulating brain bioenergetic and synaptic function [33].

Several studies pointed towards an impaired IIS pathway being involved in the pathogenesis of AD. Our study with a triple transgenic (3xTG) AD mouse model showed impairment of IIS associated with synaptic plasticity [34]. Diet-induced insulin resistance in a Tg2576 AD transgenic model promoted AD-type neuropathology [35]; intracerebroventricular streptozotocin injection to Tg2576 mice led to a brain insulin-resistant state, reduced spatial cognition, increased AD pathology, and increased mortality [36]. Intake of sucrose-sweetened water in APP/PS1 mice induced insulin resistance associated with memory impairment and Aβ accumulation in the brain [37].

In a clinical study, brain insulin resistance, IGF-1 resistance and IRS1 dysfunction, was shown to be early and common characteristics of AD [38]. Another clinical study observed severe deficiency of PI3K-Akt signaling branch of IIS accompanied by hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein in individuals with AD and type 2 diabetes mellitus [39]. A cross sectional population-based study found that features of insulin resistance were associated with AD, independent of the apolipoprotein E status [40]. A consequence from these clinical studies is the search for therapeutic options that alleviate insulin resistance and, thus, potentially halt AD progression [41].

2.2. Brain glucose uptake in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease

Studies examining brain glucose uptake have been mostly carried out using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), which allows measurement of glucose uptake but it does not represent the subsequent metabolism of glucose to CO2. FDG, upon uptake to the cell, is phosphorylated to and trapped as FDG-6-PO4, which emits a radioactive signal [42]. It is still not conclusive whether the majority of the brain glucose enters astrocytes first via GLUT1 45kDa [43] or is transported directly from blood vessels to neurons via GLUT3 [44]. The exact modus operandi for the amount of direct glucose uptake into the neurons remains unclear and this perhaps, also raises some questions about FDG-PET data interpretation.

Aging is associated with an increased risk of deteriorating systemic control of glucose and of brain glucose uptake [45]. Several pre-clinical and clinical studies seem to support a role for lowered brain glucose uptake in age-associated cognitive impairment [43]. Dynamic micro-FDG-PET scanning showed lower brain glucose uptake in aged male Fischer 344 rats compared to younger controls [32], which is also seen in chronologically and reproductively aged female rats [46, 47].

FDG-PET in human subjects exhibited focal decreases in brain activity (particularly in the medial network) as a function of normal aging [48]. Declining brain glucose uptake was also accompanied by structural changes in the brain: (a) global thinning of cerebral cortex by middle ages was observed by high-resolution, structural MRI measurements in non-demented subjects [49]; (b) a significant age dependent decline of gray matter density and cortical matching algorithms was found over the dorsal, frontal, and parietal association cortices [50], and (c) cingulate sulcus enlargement was seen with age [51].

Although there are inconsistent studies about the status of brain glucose uptake during normal aging [43], there is overwhelming evidence about lower brain glucose uptake and metabolism being associated with AD [52]. Progressive decline of brain glucose uptake in AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has been confirmed in multiple longitudinal studies. Cognitively healthy individuals with lower brain glucose uptake are more likely to be affected by MCI and/or AD dementia [53, 54]. Certain regions of the AD brain such as hippocampus, posterior cingulate, temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes have even more starkly lower brain glucose uptake [43]. Although decreased brain glucose uptake has been considered a predictor of progression to cognitive impairment or AD dementia, it still lacks enough information to allow the translation of those findings into a widely accepted diagnostic scan.

Brain glucose uptake can be separated into three steps (Fig. 2), (1) transport of glucose across the endothelium via GLUT1 (55kDa), (2) GLUT1 (45kDa) mediated transport of glucose into astrocytes, and (3) transfer of glucose into neurons via neuronal GLUTs [43]. A strong correlation has been established between decreased brain glucose uptake and decline in the expression of insulin-sensitive glucose transporters [29]. Fischer 344 rats showed decreased brain glucose uptake with age along with a parallel decrease in neuronal GLUTs. The expression of neuronal GLUT3 and GLUT4 decreased dramatically with age, whereas the expression of the vascular endothelium GLUT1 (55 kDa) decreased slightly with age [55]. Interestingly, the expression of the glia-expressed GLUT1 (45 kDa) increased with age; these results signaled towards a metabolic shift in neurons and astrocytes [32].

Similar to aging, AD is associated with decreased glucose transporter expression. In the APP/PS1 model, 18-month old mice had reduced GLUT1 expression in hippocampus compared to wildtype mice, whereas no difference were observed when they were 8 month-old [56]. In male 3xTG-AD mice, there was a decline in the neuronal GLUT3 and GLUT4 [34]. In female 3xTG-AD mice, brain glucose uptake coincided with the decrease in the expression of GLUT3 but not GLUT4; this was also associated with a rise in inactive (phosphorylated) pyruvate dehydrogenase and in ketone body metabolism [57].

GLUT1 and GLUT3 levels in six brain regions of AD patients were reduced; the decreased GLUT3 levels in certain neurons compromised glucose availability and may be responsible for the deficits in glucose metabolism [58]. Studies on postmortem brains from AD patients revealed a decreased expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3, which correlated with abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation and downregulation of HIF1α (that leads to the transcriptional activation of GLUT); interestingly, GLUT2 expression was increased, likely due to astrocyte activation [59]. A large reduction (49.5%) of GLUT3 immunoreactivity was found in the dentate gyrus, a region whose cells are selectively destroyed in AD [60]. Reduced GLUTs expression in AD have also been found at the BBB and in the cerebral cortex [61].

2.3. Mitochondrial energy metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease

Mitochondria are at the center-stage of cellular energy supply and are particularly important for the brain because 90% of the glucose (primary source of brain energy) is oxidized to CO2 in brain [62] (Fig. 3). The energy generated in this process is utilized to maintain neurotransmission and neuronal potential, and to prevent excitotoxicity [63]. Thus any alterations to neuronal glucose metabolism, largely supported by mitochondria, would affect neuronal function and ultimately affect cognition, learning, and memory.

The end metabolite of glycolysis, pyruvate, enters mitochondria via the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) [64, 65] (Fig. 3). Pyruvate is the substrate for the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH); this is a central reaction in glucose metabolism and a decreased PDH flux was observed in rodent models of aging and AD [66]. The MPC acquires further significance when considering that decrease in its activity can lead to a reduced PDH flux. Acetyl-CoA, generated by the oxidative decarboxylation catalyzed by PDH, is then metabolized in the TCA cycle. Acetyl-CoA is also a co-substrate for the synthesis of N-acetylaspartate (NAA) by Asp-NAT; NAA is the most abundant amino molecule in the brain, considered a neuronal and axonal biomarker. Its breakdown product, acetate, functions in oligodendrocytes in the biosynthesis of myelin lipids [67]. Aspartate –generated by transamination from oxaloacetate– appears to be a limiting metabolite for proliferation when deficits in the electron-transport chain occur [68, 69]. α-ketoglutarate, an intermediate of the TCA cycle, is used for the conversion of glutamate and GABA, via glutamate dehydrogenase and glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), respectively [70] (Fig. 3). Reducing equivalents (NADH) from the TCA flow through the respiratory chain and the associated oxidative phosphorylation generates ATP. The latter along with glutamate and GABA are critical for the maintenance of synaptic plasticity.

Measuring glucose metabolism via 13C-MRS/NMR involves supplying a 13C-labeled glucose followed by measuring the glycolytic end product pyruvate and the downstream TCA cycle metabolites, neurotransmitters, and neurochemicals, such as glutamate, glutamine, GABA, and NAA [71, 72]. Metabolites generated from the labeled glucose have one or multiple 13C in their structure based on how they were metabolized and the pattern of 13C labeling allows the determination of specific metabolism patterns. Thus, it is possible to follow the trail of glucose metabolism after glycolysis and estimate the amount of a specific metabolite (e.g., glutamate) generated directly from the labeled glucose. Moreover, MRS/NMR methods employing 13C-labeled substrates such as glucose and acetate allow direct assessment of neuronal and glial mitochondrial metabolism and facilitate distinguishing between them.

Mitochondrial brain glucose metabolism investigated in aged rats using [1-13C]-glucose via 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed that the incorporation of glucose-derived 13C into glutamate, glutamine, aspartate, and GABA declined in aged brain [73]. The SAMP8 mouse model of accelerated aging is characterized by spontaneous age-related learning and memory impairments associated with gliosis as a function of age [74]. SAMP8 mice, administered [1-13C]-glucose and [1,2-13C]-acetate, showed that major mitochondrial metabolites such as glutamate and glutamine derived from [1-13C]-glucose and [1,2-13C]-acetate were both significantly declined during aging [75].

13C/1H MRS studies in healthy brains showed that elderly subjects had ~30% lower neuronal mitochondrial metabolism (assessed by glutamate-glutamine cycle flux and TCA cycle flux) compared to young subjects [71, 76].. Interestingly, the astroglial rate of TCA cycle was ~30% higher in elderly group compared to young subjects, thus suggesting that normal aging was associated with a decline in neuronal metabolism along with an increase in glial metabolism as seen in astrocytes isolated from aged rats [14].

There are several studies on mitochondrion-driven glucose metabolism (measured by MRS/NMR) in rodent models of AD. Tg2576 mice showed a decrease in NAA, glutamate, and glutathione in the cerebral cortex at 19 months of age, which coincided with widespread AD-type pathology [77]. 1H-[13C]-NMR spectroscopy analyses of the APPswe-PS1dE9 mouse model of AD showed a decrease in glutamate, GABA, and glutamine, which suggested an impaired glutamatergic and GABAergic glucose oxidation and neurotransmitter cycle in these mouse brains [78]. 1H-13C spectroscopy analyses of Thy-1-APPSL model, expressing mutant human APP, suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction may contributed to the glutamine synthetase impairment and increased metabolism of glutamate via the GABA shunt [79]. Glucose metabolism was clearly reduced by ~50% in a 3xTG-AD model as exhibited by the decreased levels of metabolites derived from the TCA cycle (glutamate, glutamine, GABA, and NAA) [80]. Clinically, a pilot study in AD patients receiving [1-13C]-glucose probed for glucose metabolism using quantitative 1H and proton-decoupled 13C MR brain spectra, showed reduced glutamate neurotransmission which might contribute to cognitive impairment [81]. Interestingly, a hypermetabolic state was observed in younger triple transgenic mouse model of AD (7 months) in contrast to the hypometabolic state found in those mice that at older age (13 months). Hypermetabolism in the young AD mice was illustrated by prominent increases in 13C labeling and enrichment of metabolites (e.g. glutamate and glutamine), glycolytic activity, TCA cycle activity, and glucose cycling ratios [82]. Consistently, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy analyses after infusion of [1-13C]glucose and astrocytic substrate, [1,2-13C]-acetate on P310L Tau transgenic mice revealed a hypermetabolic state in both astrocytes and glutamatergic and GABAergic cortical neurons [83].

TCA cycle also generates the NADH that flow through the respiratory chain, tightly coupled to oxidative phosphorylation. Deficits in the mitochondrial catalytic machinery (i.e., expression and activity of the respiratory chain complexes) along with an increase in the mtDNA mutations contribute to a hypometabolic state [84, 85]. Brains of rhesus monkeys had significant reductions in complex I and complex IV activities (with correction for the variable of mitochondrial enrichment) in an age-dependent manner [86]. The activity of complex I is 30% lower in the older rat brain mitochondria compared to young animals [87].

Brain mitochondria isolated from the Thy-1 APP mouse model of AD showed a reduced COX IV activity, mitochondrial membrane potential, and ATP levels at 3 month-of-age (accompanied with increased intracellular but not extracellular Aβ). Moreover, non-TG mice treated with extracellular Aβ showed significant decline in active respiration (state 3) and maximum respiration [88]. In the 3xTG-AD model, female mice showed a decreased expression and activity of complex IV coupled with compromised oxidative phosphorylation [89]. The impairments of mitochondrial complexes were also seen in clinical studies [3, 90]: a proteomic study in AD patients found that complex III core protein-1 in the temporal cortex and the complex V β-chain in the frontal cortex were significantly reduced [91]. In another study, mitochondria from AD patients exhibited suppressed activity in all respiratory chain complexes with a dramatic decline in complex IV activity [92, 93]. Compromised mitochondrial function in AD was also related to direct effect of Aβ on mitochondrial OXPHOS. Mitochondria localized Aβ levels negatively correlated with mitochondrial respiratory function, and with cognition [94], which is consistent with another study in which Aβ was found to inhibit mitochondrial complexes I and IV activity [95].

3. Mitochondrial Redox Control in Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

Mitochondria are effective sources of H2O2, which accounts for changes in the cellular redox environment that characterizes brain aging. Oxidized redox status is a feature of AD [96, 97].

Mitochondrial H2O2 originates from dismutation of O2·−, the formation of which is accounted for by different mechanisms [98–101]. While uncontrolled production of H2O2 overwhelms the reducing capacity of the cell, regulated H2O2 participates in the redox regulation of cytosolic signaling and nuclear transcriptional pathways [102].

3.1. Mitochondrial H2O2 and redox signaling

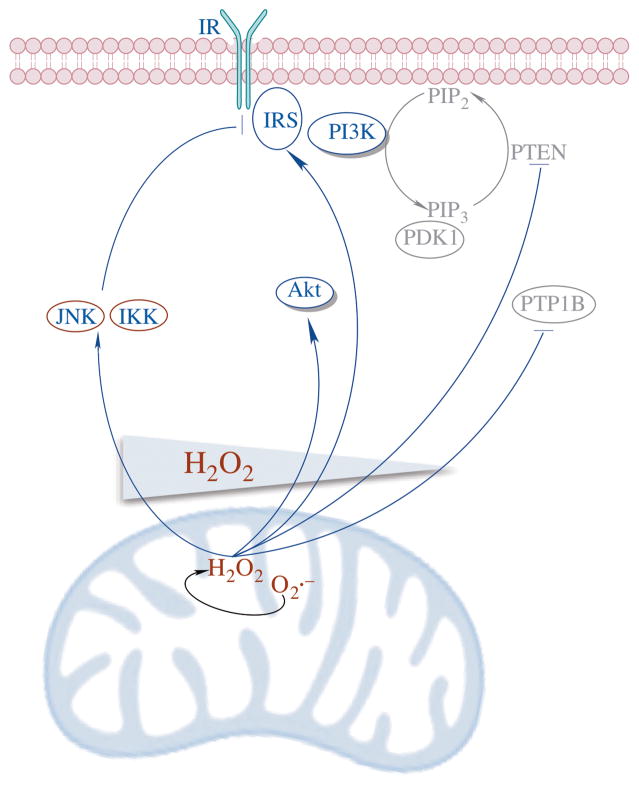

Mitochondrial H2O2 participates in the regulation of multiple cytosolic signaling pathways such as the IIS and the MAPK signaling. In neurons and hepatocytes, mitochondrion-generated H2O2 is found to activate IIS [103]. Low levels of H2O2 generated by mitochondria are actually required for the initial activation of IIS and this process is termed as “redox priming”. Collapse of the neuronal mitochondrial proton gradient by FCCP not only eliminates mitochondrial O2 consumption and H2O2 production, but also suppresses the phosphorylation (activation) of the insulin receptor even in the presence of insulin [103]. This is consistent with the observation that the spike signal of mitochondrion-generated H2O2 precedes the autophosphorylation of the insulin receptor, and that phosphorylation can be dose-dependently inhibited by N-acetylcysteine [104]. IIS is sensitive to H2O2 due to: (a) the oxidation of cysteine residues on the insulin receptor and IGF-1 receptor facilitates autophosphorylation of both receptors and leads to the activation of the downstream IRS [105] and (b) H2O2 oxidizes and inhibits two negative regulators of IIS – the tyrosine phosphatases (e.g., PTP1B) and the lipid phosphatase (PTEN) [106]. Moreover, mitochondrial H2O2 is also involved in the activation of Akt and its translocation to mitochondria and to the nucleus [107]. Nevertheless, increasing evidence suggests that H2O2 modulates IIS in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4): while lower concentrations of H2O2 (~5 μM) activate IIS, higher levels (~50 μM) inactivate IIS [108]. IIS inactivation is likely due to the stimulation by elevated H2O2 of inhibitory pathways of IIS such as JNK and IκB kinase (IKK) [19, 20], which constitutes the mechanism of stress and inflammation-induced insulin resistance, respectively [109]. The activation of JNK by H2O2 has been thoroughly investigated [110–113] and it occurs at several levels: (a) H2O2 oxidizes thioredoxin and releases the upstream kinase of JNK, ASK1 [114], (b) H2O2 oxidizes and inhibits MAPK phosphatases [115], and (c) H2O2 disrupts the glutathione transferase-JNK complex and releases the latter [116]. IIS activity (IRS1 and Akt activation) declines in both the aged rat brain and 3xTG-AD mouse brain, whereas JNK phosphorylation and activity is increased in both models with aging or with AD genotype [32, 34]. Moreover, a recent study in the same 3xTG-AD model indicates that biliverdin reductase-A (BVR-A) is also connecting oxidative changes to insulin resistance via the inactivation of BVR-A and mTOR hyperactivation [117], which is consistent with clinical data from MCI and AD subjects [118].

Fig. 4. H2O2 modulates IIS in a concentration-dependent manner.

Lower concentration of H2O2 activates IIS via (a) oxidation and activation of insulin receptor, (b) oxidation and inhibition of phosphatases that negative regulate IIS including PTP1B and PTEN, and (c) activation of Akt. Conversely, higher levels of H2O2 inactivate IIS due to the stimulation of inhibitory pathways of IIS such as JNK and IKK.

3.2. The Mitochondrial Redox System

Maintenance of the mitochondrial redox status is determined by the balance between the sources of H2O2 and its reduction to H2O by the glutathione peroxidase (GPx)-GSH and thioredoxin-2 (Trx2)-peroxiredoxins systems.

GSH-supported system

GSH synthesized in cytosol enters mitochondria and provides reducing equivalents to GPxs for H2O2 removal [119]. GPx1 localized in the matrix and GPx4 in the inter-membrane space are the two major GPx isoforms associated with mitochondria. While GPx1 is primarily involved in reducing H2O2 in mitochondrial matrix, GPx4 in both the cytosol and the mitochondria is vital to protect the cell from lipid hyperoxidation [120, 121]. GSH is regenerated from GSSG by glutathione reductase using reducing equivalents from NADPH. Mitochondrial GSH levels positively correlate with cellular viability [122, 123]. In both neurons and astrocytes, depletion of mitochondrial GSH leads to an increase in H2O2, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, as well as cell death [124, 125]. Reagents that increase mitochondria GSH levels protect neurons against oxidant-induced neurotoxicity [126]. During aging, oxidation of mitochondrial GSH to GSSG [127, 128] is accompanied by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) oxidation in rodents [129, 130]. A clinical study to noninvasively quantify GSH in the occipital cortex of healthy young and old human subjects suggests that the old group has ~30% lower GSH levels than the young group [131]. The age-dependent decline in GSH levels in brain has also been connected with impaired cognitive function in aging. Treatment of rodents with compounds that acutely deplete GSH in the brain results in deficits in short-term spacing memory as well as impairment of LTP [132, 133].

Trx-supported peroxiredoxin system

In this system, electrons are transmitted from NADPH to Trx2 by thioredoxin reductase 2 (TrxR2) and eventually to H2O2 via peroxiredoxins [134]. Prx3 and Prx5 are the two mitochondrial Prxs that reduce H2O2, organic hydroperoxides, and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [135]. Prx3 catalyzes the removal of up to 90% of mitochondrial H2O2 especially at low H2O2 levels due to its high reaction rate constant (107 M−1s−1) [136]. Real time monitoring indicates that the removal of H2O2 in brain mitochondria is primarily a function of the Trx/Prx system with the GSH/GPx system contribute a small percentage [137]. Interestingly, high concentrations of H2O2 suppresses the peroxidase activity of Prx3 by hyperoxidizing it to the sulfinic acid form (Prx3-Cys-SO2H) [138], which can be converted back to the sulfenic acid form (Prx3-Cys-SOH) through an ATP-dependent reaction catalyzed by sulfiredoxin (Srx) translocated into mitochondria [139, 140]. During aging, the inactivated, hyperoxidized Prx3 accumulates in liver mitochondria, with the reduced form remains the same as that of young rats [141]. This study confirms the increased H2O2 production and oxidized redox status in aged mitochondria. The imbalance between reduced and hyperoxidized Prx3 that occurred with aging could be ascribed to a decreased Srx activity in mitochondria and to the decline in mitochondrial protease activity involving the matrix-localized, ATP-stimulated Lon protease [142].

In the brain, Prx3 protects neurons against excitotoxicity while it suppresses astrocyte proliferation in specific brain regions [143]. Prx3 was also found to be involved in various neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Down syndrome [144]. AD patients exhibit a significantly lower expression of Prx3 in the brain than the normal subjects [145]. In AD mouse models, Prx3 overexpression protects both the APP transgenic- or non-transgenic mice from mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive decline [146]. Prx3 transgenic mice exhibited enhanced mitochondrial function coupled with reduced oxidative stress compared with control group; relative to the APP single transgenic mice, APP+Prx3 double transgenic mice exhibited enhanced mitochondrial function, improved cognition, and reduced brain Aβ loading [146].

Prx5 is a 17 kDa atypical 2-Cys Prx [147]. In addition to mitochondria, Prx5 occurs in other intracellular compartments such as peroxisome, cytosol, and nucleus. Prx5 has a higher reaction rate with peroxynitrite and alkyl hydroperoxides than that with H2O2 and, unlike Prx3, it is insensitive to H2O2 hyperoxidation [148]. Prx5-deficient cells have increased oxidative macromolecule damage and are more susceptible to cell death [149, 150]. Conversely, overexpressing Prx5 in CHO cells protects mtDNA from H2O2 induced oxidation [151].

In addition to being a H2O2 scavenger, oxidized Prx1 and Prx2 could act as a H2O2 signal receptor and transduce signals to redox-sensitive target proteins [152, 153]. By forming a transient mixed disulfide intermediate with a nearby target protein, H2O2-oxidized Prx transmits redox signals from H2O2 to that target protein. The target protein, rather than Prx itself, is later reduced by Trx [152, 153]. These studies suggest a new paradigm in redox signaling that allows the spatiotemporally precise regulation of redox-sensitive proteins especially those that have a low intrinsic reactivity with H2O2, such as some transcription factors and kinases. It is still to be determined whether mitochondrial Prxs are involved in this redox relay to facilitate H2O2 oxidation of mitochondrial proteins.

The intermolecular disulfide formed upon H2O2-driven oxidation of the two cysteine residues of Prx3 is reduced back by Trx2 in mitochondria [154]. Trx2 is abundantly expressed in mitochondria of tissues with high metabolic rate [155]. Trx2 is involved in apoptosis by interacting with the mitochondrion-localized apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1). When Trx2 is oxidized by inflammatory or oxidative stimuli, ASK1 disassociates from Trx2 and phosphorylates downstream pro-apoptotic kinases such as p38 and JNK [156]. Interestingly, the Trx system is also implicated in the long-living Ames dwarf mouse. In these growth hormone (GH)-deficient mice, the expression and activity of both Trx2 and thioredoxin reductase-2 (TrxR2) are higher than those in the wild type mice. Such an upregulation of Trx2 system in these long-living mice is reversed by a 7-day treatment of GH [157], suggesting the correlation among reduced GH signaling, enhanced oxidative stress resistance, and extended life span. The expression of Trx2 in hippocampi of AD brains is significantly lower than that in control brains [158].

The expression of TrxR2, that catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of oxidized Trx2, decreases with age in multiple tissues [159]. TrxR2, together with NADPH supply, could be key aspects that account for the dysregulated redox status during aging and neurodegeneration [160].

3.3. Interconnected mitochondrial energy- and redox systems

Both the GSH and Trx systems in mitochondria use NADPH as the ultimate reducing equivalent through glutathione reductase and TrxR, respectively. Sources of NADPH in mitochondria are the activities of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT), isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2), and malic enzyme, with the NNT accounting for ~50% of the total NADPH production [161].

Under physiological conditions, NNT catalyzes the reduction of NADP+ to NADPH using electrons from NADH and proton gradient force built on the mitochondrial inner membrane [162]. The mitochondrial energy-transducing component is thus connected with the mitochondrial redox system by NNT, given that the NADH is primarily generated in TCA cycle, and that the proton gradient is built by the electron transport chain. Oxidative challenges by cigarette smoke, which contains high amount of oxidants and electrophiles, upregulates NNT expression [163]. Silencing of NNT in PC12 cells leads to lowered ratios of NADPH/NADP+ and GSH/GSSG, elevated H2O2 production, and compromised mitochondrial metabolic capacity. NNT suppression also induces accumulation of oxidized mitochondrial Prx3 [164], as well as the activation of intrinsic apoptosis through the activation of redox-sensitive JNK pathway [112]. The activity of NNT in male Fischer 344 rats declines as a function of age in 6-, 14-, and 26 month-old rats (Yin et al., unpublished data). NNT expression in mouse brain also declines during aging from middle age (11 month) to old (21 month) and its expression is lower in brains of the 3xTG-AD mice at both 11- and 21-month, compared to age-matched non-TG controls [165].

Under some pathological conditions, NNT in heart catalyzed the reverse reaction to generate NADH using reducing power from NADPH [166]. Upon increased metabolic demand, NNT switches to the reverse mode and consumes NADPH for NADH production, which impairs the capacity of mitochondrial redox systems to remove H2O2 and ultimately results in oxidative stress and cell death [166]. The activation mechanism of NNT reverse mode requires further investigation as well as involvement of this mechanism in tissues other than the heart, such as the brain.

Mitochondrial energy status determines redox capacity via NADPH-generating enzymes such as NNT and IDH2. On the other side, perturbations of the mitochondrial redox status alter the bioenergetic function via oxidative- or nitrosative post-translational modifications of key metabolic enzymes, including aconitase [167], α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase [168], malate dehydrogenase (MDH) [169], succinyl-CoA-3-oxaloacid CoA transferase (SCOT) [170, 171] and complexes I [172], II [173], and V [170, 171] (for detailed review, see [15]). While oxidative modifications of these enzymes mostly lead to the inhibition of their activity in MCI or AD, the activity of MDH was found to be increased in MCI [174, 175]. Moreover, cytosolic redox status affects the utilization of different fuel substrates for energy transducing within the mitochondria by modulating cytosolic glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [176, 177]. In lung cells, oxidative reagents such as cigarette smoke or acrolein suppress glycolysis and glucose-dependent ATP production by oxidizing and inhibiting the glycolytic enzyme, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). This suppression of glycolysis reroutes glucose to the PPP to generate more NADPH to combat oxidative challenges [176, 177]. Due to the limited pyruvate transport into mitochondria, fatty acid transporters including carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) and cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) are upregulated, thus enhancing the utilization of fatty acids as fuel substrates. This shift in energy substrates reduces fatty acid supply to the surfactant biosynthesis and is thus implicated in the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [176, 177]. These studies extend the inter-regulations between the mitochondrial energy and redox pathways to their cytosolic counterparts.

4. Inflammatory Responses in Brain Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

The immune privilege of the CNS prevents circulating immune cells from gaining access to it without the occurrence of inflammation or injury [178]. While a prolonged inflammatory state in the brain is detrimental to its function, the brain innate immune system can also be beneficial, since it promotes cellular repair and clears debris.

4.1. Brain cell types involved in neuroinflammation

Microglia is the major effector of the innate immune system and are ubiquitously distributed in the brain. Microglia use highly motile processes to survey nearby regions for the presence of pathogens and cellular debris, while synthesizing factors important for tissue maintenance. Microglia also help maintain plasticity of the neuronal circuits, and contribute to the protection and remodeling of synapses. These functions of microglia are partly mediated by the release of trophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is important for memory formation and learning. Upon activation by pathological triggers, microglia migrate to the site of injury, where they initiate an immune response. Changes in the function or activity of microglia, as a result of aging or neurodegeneration, may contribute to pathology progression. Along with microglia, astrocytes and endothelial cells also express innate immune receptors and contribute to inflammatory responses in the brain [179]. While astrocytes are mainly involved in maintaining neuronal function, they are also known to mediate neuroinflammation by receiving and amplifying inflammatory signals from microglia, and form the self-propagating cytokine cycle which generates large amounts of cytokines and oxidative signals [180].

4.2. Molecular components in inflammatory response

An inflammatory response typically involves three stages: TLR-NFκB formation of procytokines, inflammasome assembly, and activation of caspase-1. The detection of pathological triggers in an inflammatory response is mediated by pattern recognition receptor (PRRs) such as TLRs that recognize danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The downstream signaling pathways affected regulate the activities of transcription factors NFκB and AP-1, which induces the expression of effector proteins, such as components of the inflammasome (e.g., NLRP3, NLRP1, NLRC4), cytokines, oxidants and NO.

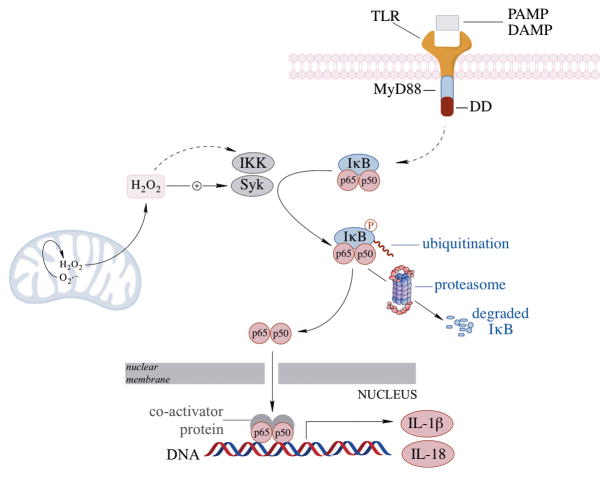

NFκB signaling

NFκB regulates immune responses through the transcriptional regulation of cytokines and immune response genes [181]. Under basal conditions, In response to stimuli-induced phosphorylation of IκB, NFκB dissociates from the complex and translocates from cytosol to the nucleus to induce the transcription of its target genes [182] (Fig. 5). NFκB is sensitive to redox changes and inflammatory mediators and participates both protective and damaging responses, based on the context of stimulation. H2O2 can positively or negatively modulate NFκB activity. Mitochondria-derived H2O2 is key to the activation of NFκB [20, 183]. Although excessive levels of H2O2 inactivate NFκB through oxidation of its p50 subunit, moderate levels of H2O2 lead to IKK- or Syk-induced phosphorylation, polyubiquitination, and degradation of IκB, and the activation of NFκB [184, 185] (Fig. 5). NFκB can have a pro-survival role by inhibiting JNK, upregulating anti-apoptotic genes, and decreasing the expression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD). Conversely, NFκB activation can be damaging to cells by initiating and amplifying inflammatory gene expression [186–188]. NFκB and MAPK pathway activation is apparent in oxidative stress and Aβ-induced neuronal cell death [189–191]. Interestingly, the outcomes of NFκB activation can be age-dependent: its activation by TNFα is neuroprotective against excitotoxicity and ischemic brain injury in 10 month-old neurons, but the same stimulus in 24 month old neurons was shown to be toxic [192].

Fig. 5. NFκB signaling in the inflammatory response.

NFκB activation, and subsequent translocation to the nucleus can be initiated by different PAMPs or DAMPs via the toll-like receptors (e.g., TLR4). Mitochondrial H2O2 can facilitate NFκB activation by modulating the redox sensitive Syk and IKK pathways which phosphorylate the inhibitory protein IκB and lead to IκB ubiquitination and degradation, thereby releasing NFκB and its translocation to the nucleus.

Inflammasomes

Cellular insults identified by PRRs activate cytosolic multiprotein complexes called inflammasomes, which are responsible for the maturation and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the activation of pyroptosis, an inflammatory form of cell death [193]. The inflammasomes are either members of the NLR family or members of the pyrin and HIN domain-containing (PYHIN) family [194]. A total of 23 genes encode the NLRs, but only a few are capable of forming oligomeric complexes that activate caspase-1 [195], including NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP12 and NLRC4 [196, 197]. The activation of most inflammasomes requires a priming stimulus (signal 1) and an activating stimulus (signal 2). Inflammasome complexes are generally composed of three components: a cytosolic PRR, caspase-1, and an adaptor protein, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain). A priming stimulus, through activation of NFκB signaling, often leads to assembly of the inflammasome complex, which increases expression of prointerleukin-1β (pro-IL1β) and the inflammasome (e.g., NLRP3). Activated inflammasomes oligomerize to form a platform with ASC that can activate caspase-1 (Fig. 6). ASC facilitates interaction between the PYD domain of the NLRP proteins and the CARD of procaspase-1. Caspase-1 regulates the maturation and release of IL-1β and IL-18 and also triggers pyroptosis pathways [194].

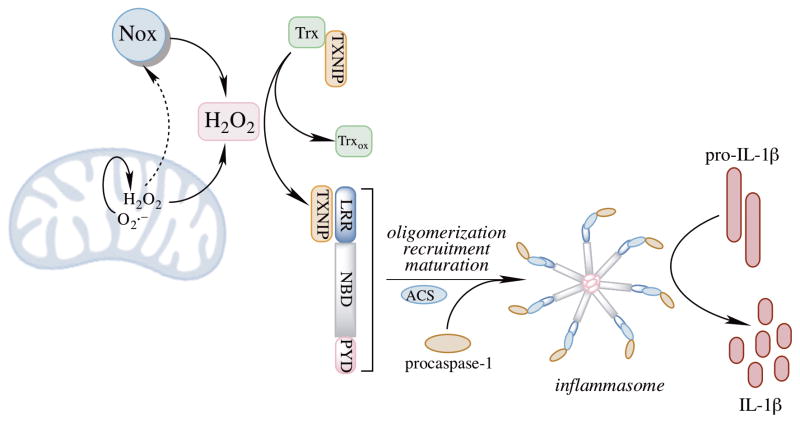

Fig. 6. Mitochondrion-driven activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

H2O2 generated by mitochondria and NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes are major sources for NLRP3 priming and activation. NOX enzymes are dependent on mitochondrial H2O2 for their activation. Once primed, the inflammasome components oligomerize and form a complex with ACS, generating a platform for caspase-1 to catalyze the proteolytic activation of IL1β.

NLRP3 inflammasome is the most widely studied member of the NLR family. It can be activated by a wide array of stimuli, including APMPs such as bacterial, fungal and viral components, as well as DAMPs such as extracellular ATP, and it can also be stimulated by H2O2 and amyloid-β in the brain. Its ability to respond to a wide variety of stimuli suggests that it behaves as a general sensor of cellular damage and stress. The activity of NLRP3 seems crucial in the pathogenesis of different degenerative disorders such as AD, atherosclerosis, liver cirrhosis, and lung fibrosis [194].

The exact activation mechanism of the NLRP3 inflammasome is under debate, but all the proposed models postulate that cytoplasmic K+ concentration plays a crucial role. Three models have been proposed. (a) The channel model proposes extracellular ATP to be the main activator, which activates the P2X7 K+ release channel, which ultimately gives rise to pannexin 1 pore formation. The pores (which can be formed by bacterial toxins as well) allow cytoplasmic entry of extracellular factors that directly activate NLRP3 and also allow K+ efflux out of the cell [198, 199]. (b) The lysosome rupture model fits when the activating stimuli are particulate activators (e.g., alum and silica). It proposes that these particles are phagocytosed, causing lysosomal rupture release of Cathepsin B into the cytoplasm, which activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [200, 201]. (c) The H2O2 model, being the most relevant model in the context of this review, proposes NLRP3 to be a general sensor of cellular stress, where H2O2 serves as the secondary messenger that activates the inflammasome [202, 203] (Fig. 6)., and it will be particularly discussed.

4.3. Redox regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome

All NLRP3 activators have been found to be able to trigger oxidant production, whereas treatment with antioxidants blocks NLRP3 activation [204]. H2O2-triggered binding of NLRP3 to Trx-interacting protein (TXNIP), production is proposed to be the mechanism underlying the redox activation of NLRP3 [202]. Under resting mode, TXNIP is bound to Trx [205] and increased cellular H2O2 production dissociates this complex, thereby allowing TXNIP to bind to NLRP3, thus and leading to the activation of the latter (Fig. 6). Knockdown of Trx potentiated inflammasome activation and knockdown of TXNIP inhibited activation of caspase-1 and IL1β secretion upon stimulation by NLRP3 agonists [202, 206]. However, caspase-1 activation is not completely blocked when TXNIP is knocked out, suggesting that there are multiple pathways being capable of activating NLRP3. Redox changes are also important in priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Priming of the inflammasome, which involves the TLR/NFκB signaling, can occur through its deubiquitination in the presence of mitochondrial H2O2 [195]. Several questions about the oxidant-dependent model of NLRP3 activation remain unresolved, and not all the stimuli that lead to oxidant production were able to activate NLRP3 (e.g., TNFα). This implies that activation of NLRP3 follows a specific mechanistic pathway, in which oxidants or specifically H2O2 are essential but are not sufficient. In addition, in contrast to the H2O2 model of NLRP3 activation, O2·− was found to inhibit caspase-1 activation via redox signaling [207].

NADPH oxidases (NOX) were initially thought to be the primary activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome via the production of O2·− and H2O2. Some early inflammasome studies reported the NOX enzymes to be important in activating NLRP3 in response to ATP and particulates [206, 208]. However, macrophages deficient in certain NOX subunits, like NOX1, NOX2, NOX3, and NOX4, responded normally to activating stimuli, and in some cases, demonstrated slightly increased inflammasome activity, suggesting either compensation by remaining members of the NOX family or occurrence of a other cellular sources of oxidants for inflammasome activation [209]. In the CNS, NOX function is required for proper neuronal signaling and cognitive function, but overproduction of superoxide radicals contributes to neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration [210]. Increased activation of microglial NOX enzymes was found in the brains of AD patients [211]. However, in normal aging mouse brains, NOX activity was only upregulated in the 24-month-old mice when challenged by a high fat diet [212], suggesting age-related increase in sensitivity to activating stimuli in the brain.

Recent studies suggest that mitochondria might be the organelles that integrate signaling for inflammasome activation [209]. There is also evidence showing that NOX activation (and the generation of O2·− and H2O2) requires initial priming by mitochondrial H2O2 [213]. In non-stimulated conditions, the NLRP3 protein is localized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) but not mitochondria. This localization changed upon activation of the inflammasome in response to several different stimuli: NLRP3 translocated to the perinuclear space, where it also co-localized with ER and mitochondria. A similar ER/mitochondrial co-localization was observed for ASC upon NLRP3 activation, and TXNIP was found to redistribute to the mitochondria upon inflammasome activation. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA or inactivation of the voltage dependent ion channel (VDAC) was shown to impair inflammasome activation. VDAC proteins, abundant in the outer mitochondrial membrane, are channels responsible for ions and metabolite exchange between mitochondria and the rest of the cell, particularly the ER. They are also involved in the regulation of mitochondrial metabolism and mitochondrial O2·− release [214], and their nitration is significantly increased, indicative of changes in redox homeostasis, in AD brains [215]. Additionally, inhibition of mitophagy/autophagy by 2-methyladenine resulted in the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria with increased oxidant production, and as a consequence, inflammasome was activated [209]. Other mitochondrion-generated oxidants, such as ONOO− and O2·− can also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [216, 217].

4.4. NLRP3 at the interface of inflammation and metabolism

The first link between inflammation and metabolism originated from early studies in models of obesity, where the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β was upregulated in adipose tissues of obese and diabetic subjects. The NLRP3 inflammasome, which regulates the secretion of IL-1β, is considered to be a sensor of altered metabolic homeostasis and its activation is thought to induce insulin resistance. Increased activity of NLRP3 was also implicated in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome [218], with insulin hypersensitivity being the primary phenotype of the NLRP3- or caspase-1-deficient mice [219, 220]. Interestingly, deficiency of IL-1β protects rodents from insulin resistance induced by high-fat diet [220, 221], and the treatment with an IL-1 receptor antagonist reduced hyperglycemia in diabetic rodents and improved glycemic control in type-2-diabetes patients [222, 223]. Studies using genetic mouse models demonstrated that IL-1β inhibits IIS by upregulating TNFα, a known insulin resistance-promoting cytokine [224, 225]. Although it is not clear whether or not the NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to neuronal insulin resistance, it is likely that a similar mechanism to that in adipose tissue might be prevalent in the CNS.

Conversely, metabolic signals (from mitochondria) can modulate inflammatory response. Mitochondrion-derived DAMPs, such as mtDNA, can directly induce inflammatory changes in microglial and neuronal cells [226], although the oxidation of mtDNA is still required [227], which supports the notion that redox control is the linking component transducing metabolic signal to inflammatory response. In addition, extracellular ATP at various concentrations can activate microglia and induce neuroprotective or neurotoxic effects by the expression of pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines [228, 229].

4.5. Neuroinflammation in aging and Alzheimer’s disease

Several of the inflammatory factors discussed above can be general neurotoxic factors in normal aging and neurodegenerative diseases. It is predicted that these inflammatory responses are partly driven by positive feedback loops between microglia and astrocytes. Amplification of inflammation by astrocytes worsens the neurotoxic environment and the damaged neurons can further activate glial cells by releasing ATP and other DAMPs. This encompasses a self-promoting cycle of inflammation and neuronal death, even after the withdrawal of initial stimuli. This inflammatory mechanism is hypothesized to cause neurodegeneration and set the foundation of neurological disorders such as AD [13].

Chronic, low-grade inflammation positively correlates with aging: with age, microglia exhibit enhanced sensitivity (priming) to inflammatory stimuli (originating either from peripheral tissues or brain), similar to that observed in brains with ongoing neurodegeneration [230]. In both physiologically aged and senescence-accelerated mouse models, profound microglia priming was characterized by increased basal production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα), decreased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10), decreased activity of the TGFβ1-Smad3 signaling pathway, and upregulated TLR expression. This age-related increase in microglial activation negatively impacts brain function [231]. NLRP3-deficient mice on a high-fat diet showed lower incidence of astrogliosis as compared to the age-matched wildtype mice. Furthermore, these NLRP3-deficient mice were significantly protected from age-related decline in cognition and memory [232]. The same study also suggested that IL-1β signaling, downstream of NLRP3 activation, modulates the age-related functional decline in the brain by the deletion of IL-1 receptor. Aging is also associated with dysregulation of microglia, with deficits in CD200 and fractalkine regulation. Similarly, astrocytes also exhibit pro-inflammatory phenotypes during aging: an increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 was observed in the rat cortex and striatum during aging [233].

In the Alzheimer’s brain, Aβ is capable of activating microglia and astrocytes to induce production of damaging molecules such as H2O2, NO, pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins (e.g., PGE2), which cause neuronal death [234]. Aβ plaques can be detected through several sensors, including TLRs, NLRs, and RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end products) [204, 235–237]. Aβ oligomers and fibril-induced lysosomal damage can trigger activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [201]. In neurons, NALP1, a member of the NLR family, can induce inflammatory response, similar to NLRP3 [238]. These inflammatory signals, along with other risk factors converge to produce an abnormal processing of the tau protein [239]. Although neuroinflammation can facilitate the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) through tau kinases, it is not clear that whether these NFTs affect inflammatory responses [13, 240].

Despite the critical involvement of inflammatory processes in AD etiology, the use of anti-inflammatory drugs have produced minimum to no beneficial effects on symptomatic AD [241]. In these studies, anti-inflammatory drugs sometimes exhibit adverse effect in later stages of AD pathogenesis [241], although it was also found that long-term use of certain NSAIDs can reduce AD risk significantly with asymptomatic subjects [242, 243]. Interestingly, in another study, it was shown that AD risk reduction with NSAIDs only in participants having an APOE epsilon 4 allele [244], indicating the critical role of APOE status in AD-associated neuroinflammation. While the reasons for the failures in these epidemiological studies could be study design-based (such as the time and dose of intervention), one cannot ignore the fact that the pro-inflammatory environment in the AD brain is necessary for activating microglia- that clear Aβ [245], and even support neurogenesis after damage [246]. Therefore, it is hypothesized that anti-inflammatory drugs might only be beneficial in the early stages of AD (before the deposition of Aβ), direct evidence for which is yet to be seen [241].

5. Concluding remarks

Compromised glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function are signatures of normal brain aging and early stages of AD, while neuroinflammation is also observed in brain aging and the late stage of AD animal models and postmortem AD brains. It is still debatable whether or not neuroinflammation is the driven force of brain aging and AD or it is simply a consequence of metabolic dysfunction occurring earlier in the progression of aging or AD. It is noteworthy that although dysregulated neuroinflammation induces neurotoxicity and tissue damage, the primary function of controlled immune responses is still to protect the brain from infectious agent and injuries. Nevertheless, an increasing number of studies on cell lines, genetic rodent models, and humans indicate that redox control might serve as a bidirectional link between energy metabolism and inflammatory responses in the brain. The brain metabolic-inflammatory axis entails interconnected cross-talks of energy metabolism, redox control, and neuroinflammation (Fig. 7) and might serve as an integrated mechanism for brain aging and Alzheimer’s etiology.

Fig. 7. Coordination of metabolic, redox, and inflammatory signals in brain aging and neurodegeneration.

The metabolic-, redox- and inflammatory components are interconnected and signals (metabolic signal: ATP; redox signal: H2O2 and NO; inflammatory signal: cytokines) originated from each component are involved in intra- (inner circle) and inter- (outer circle) cellular communications in the brain.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01AG016718 to EC and P01AG026572 to Roberta D. Brinton, project 1 to EC.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Akt

protein kinase B

- AMPK

5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- ASK

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GH

growth hormone

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- HIF1-α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α

- IGF1

insulin-like factor 1

- IIS

insulin/IGF1 signaling

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IRS

insulin receptor substrate

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MPC

mitochondrial pyruvate carrier

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NAA

N-acetylaspartate

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NNT

nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase

- Prx

peroxiredoxins

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- Trx

thioredoxin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Imtiaz B, Tolppanen AM, Kivipelto M, Soininen H. Future directions in Alzheimer’s disease from risk factors to prevention. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:661–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi S, Zanier ER, Mauri I, Columbo A, Stocchetti N. Brain temperature, body core temperature, and intracranial pressure in acute cerebral damage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:448–454. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blass JP, Sheu RK, Gibson GE. Inherent abnormalities in energy metabolism in Alzheimer disease. Interaction with cerebrovascular compromise. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;903:204–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Khan SM. The Alzheimer’s disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S265–279. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de la Monte S, Wands J. Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:45–61. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science. 2014;346:587–591. doi: 10.1126/science.1254405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Heemst D. Insulin, IGF-1 and longevity. Aging Dis. 2010;1:147–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Z, Tseng Y, White MF. Insulin signaling meets mitochondria in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow RH. Brain aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1630–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Felice FG, Ferreira ST. Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as common molecular denominators connecting type 2 diabetes to Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2014;63:2262–2272. doi: 10.2337/db13-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spielman LJ, Little JP, Klegeris A. Inflammation and insulin/IGF-1 resistance as the possible link between obesity and neurodegeneration. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;273:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapetanovic R, Bokil NJ, Sweet MJ. Innate immune perturbations, accumulating DAMPs and inflammasome dysregulation: A ticking time bomb in ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang T, Cadenas E. Astrocytic metabolic and inflammatory changes as a function of age. Aging Cell. 2014;13:1059–1067. doi: 10.1111/acel.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin F, Boveris A, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial energy metabolism and redox signaling in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:353–371. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin F, Sancheti H, Liu Z, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial function in ageing: coordination with signalling and transcriptional pathways. J Physiol. 2015:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1113/JP270541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taneguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nature Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen E, Dillin A. The insulin paradox: aging, proteotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:759–767. doi: 10.1038/nrn2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin F, Jiang T, Cadenas E. Metabolic triad in brain aging: mitochondria, insulin/IGF-1 signalling, and JNK signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:101–105. doi: 10.1042/BST20120260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csiszar A, Wang M, Lakatta EG, Ungvari Z. Inflammation and endothelial dysfunction during aging: role of NF-κB. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1333–1341. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90470.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowell BB, Shulman GI. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2005;307:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1104343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havrankova J, Roth J, Brownstein MJ. Concentrations of insulin and insulin receptors in the brain are independent of peripheral insulin levels. Studies of obese and streptozotocin-treated rodents. J Clin Invest. 1979;64:636–642. doi: 10.1172/JCI109504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heide LP, Ramakers GM, Smidt MP. Insulin signaling in the central nervous system: learning to survive. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grillo CA, Piroli GG, Hendry RM, Reagan LP. Insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane in rat hippocampus is PI3-kinase dependent. Brain Res. 2009;1296:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brüning J, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, Klein R, Krone W, Müller-Wieland D, Kahn CR. Role of Brain Insulin Receptor in Control of Body Weight and Reproduction. Science. 2000;289:2122–2125. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang RA. C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman DB, Johnson TE. A mutation in the age-1 gene in Caenorhabditis elegans lengthens life and reduces hermaphrodite fertility. Genetics. 1988;118:75–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bluher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taguchi A, Wartschow LM, White MF. Brain IRS2 Signaling Coordinates Life Span and Nutrient Homeostasis. Science. 2007;317:369–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1142179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barzilai N, Ferrucci L. Insulin Resistance and Aging: A Cause or a Protective Response? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mair W, Dillin A. Aging and survival: the genetics of life span extension by dietary restriction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:727–754. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061206.171059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang T, Yin F, Yao J, Brinton RD, Cadenas E. Lipoic acid restores age-associated impairment of brain energy metabolism through the modulation of Akt/JNK signaling and PGC1a transcriptional pathway. Aging Cell. 2013;12:1021–1031. doi: 10.1111/acel.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Z, Patil IY, Jiang T, Sancheti H, Walsh JP, Stiles BL, Yin F, Cadenas E. High-fat diet induces hepatic insulin resistance and impairment of synaptic plasticity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sancheti H, Akopian G, Yin F, Brinton RD, Walsh JP, Cadenas E. Age-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity and insulin mimetic effect of lipoic acid on a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho L, Qin W, Pompl PN, Xiang Z, Wang J, Zhao Z, Peng Y, Cambareri G, Rocher A, Mobbs CV. Diet-induced insulin resistance promotes amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2004;18:902–904. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0978fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plaschke K, Kopitz J, Siegelin M, Schliebs R, Salkovic-Petrisic M, Riederer P, Hoyer S. Insulin-resistant brain state after intracerebroventricular streptozotocin injection exacerbates Alzheimer-like changes in Tg2576 AbetaPP-overexpressing mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;19:691–704. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao D, Lu H, Lewis TL, Li L. Intake of sucrose-sweetened water induces insulin resistance and exacerbates memory deficits and amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36275–36282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talbot K, Wang HY, Kazi H, Han LY, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, Fuino RL, Kawaguchi KR, Samoyedny AJ, Wilson RS, Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wolf BA, Bennett DA, Trojanowski JQ, Arnold SE. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1316–1338. doi: 10.1172/JCI59903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong C-X. Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. J Pathol. 2011;225:54–62. doi: 10.1002/path.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuusisto J, Koivisto K, Mykkänen L, Helkala EL, Vanhanen M, Hänninen T, Kervinen K, Kesäniemi YA, Riekkinen PJ, Laakso M. Association between features of the insulin resistance syndrome and alzheimer’s disease independently of apolipoprotein e4 phenotype: cross sectional population based study. BMJ. 1997;315:1045–1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craft S, Cholerton B, Baker LD. Insulin and Alzheimer’s disease: untangling the web. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S263–275. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teune LK, Bartels AL, Leenders KL. FDG-PET imaging in neurodegenerative brain diseases. In: Signorelli F, Chirchiglia D, editors. Functional brain mapping and the endeavor to understand the working brain. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cunnane S, Nugent S, Roy M, Courchesne-Loyer A, Croteau E, Tremblay S, Castellano A, Pifferi F, Bocti C, Paquet N, Begdouri H, Bentourkia M, Turcotte E, Allard M, Barberger-Gateau P, Fulop T, Rapoport SI. Brain fuel metabolism, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrition. 2011;27:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mergenthaler P, Lindauer U, Dienel GA, Meisel A. Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Craft S. Insulin resistance syndrome and alzheimer disease: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:298–301. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213866.86934.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gage FH, Kelly PA, Bjorklund A. Regional changes in brain glucose metabolism reflect cognitive impairments in aged rats. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2856–2865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02856.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin F, Yao J, Sancheti H, Feng T, Melcangi RC, Morgan TE, Finch CE, Pike CJ, Mack WJ, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. The perimenopausal aging transition in the female rat brain: decline in bioenergetic systems and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2282–2295. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pardo JV, Lee JT, Sheikh SA, Surerus-Johnson C, Shah H, Munch KR, Carlis JV, Lewis SM, Kuskowski MA, Dysken MW. Where the brain grows old: Decline in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal function with normal aging. Neuroimage. 2007;35:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salat DH, Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Greve DN, Desikan RS, Busa E, Morris JC, Dale AM, Fischl B. Thinning of the Cerebral Cortex in Aging. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:721–730. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW. Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kochunov P, Mangin JF, Coyle T, Lancaster J, Thompson P, Riviere D, Cointepas Y, Régis J, Schlosser A, Royall DR. Age-related morphology trends of cortical sulci. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;26:210–220. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mosconi L, Tsui WH, Herholz K, Pupi A, Drzezga A, Lucignani G, Reiman EM, Holthoff V, Kalbe E, Sorbi S, Diehl-Schmid J, Perneczky R, Clerici F, Caselli R, Beuthien-Baumann B, Kurz A, Minoshima S, de Leon MJ. Multicenter Standardized 18F-FDG PET Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Other Dementias. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:390–398. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mosconi L, Tsui WH, Pupi A, De Santi S, Drzezga A, Minoshima S, de Leon MJ. 18F-FDG PET Database of Longitudinally Confirmed Healthy Elderly Individuals Improves Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1129–1134. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alexander GE, Chen K, Pietrini P, Rapoport SI, Reiman EM. Longitudinal PET Evaluation of Cerebral Metabolic Decline in Dementia: A Potential Outcome Measure in Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment Studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:738–745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mooradian AD, Morin AM, Cipp LJ, Haspel HC. Glucose transport is reduced in the blood-brain barrier of aged rats. Brain Res. 1991;551:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90926-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hooijmans CR, Graven C, Dederen PJ, Tanila H, van Groen T, Kiliaan AJ. Amyloid beta deposition is related to decreased glucose transporter-1 levels and hippocampal atrophy in brains of aged APP/PS1 mice. Brain Res. 2007;1181:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ding F, Yao J, Rettberg JR, Chen S, Brinton RD. Early decline in glucose transport and metabolism precedes shift to ketogenic system in female aging and Alzheimer’s mouse brain: implication for bioenergetic intervention. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simpson IA, Chundu KR, Davies-Hill T, Honer WG, Davies P. Decreased concentrations of GLUT1 and GLUT3 glucose transporters in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:546–551. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]