Abstract

Family history of cancer is a risk factor for gastric cancer. In this study, we investigated the prognoses of gastric cancer patients with family history of cancer. A total of 1805 gastric cancer patients who underwent curative gastrectomy from 2000 to 2008 were evaluated. The clinicopathologic parameters and prognoses of gastric cancer patients with a positive family history (PFH) of cancer were compared with those with a negative family history (NFH). Of 1805 patients, 382 (21.2%) patients had a positive family history of cancer. Positive family history of cancer correlated with younger age, more frequent alcohol and tobacco use, worse differentiation, smaller tumor size, and more frequent tumor location in the lower 1/3 of the stomach. The prognoses of patients with a positive family history of cancer were better than that of patients with a negative family history. Family history of cancer independently correlated with better prognosis after curative gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients.

Keywords: gastric cancer, prognosis, cancer family history

INTRODUCTION

Despite decreasing incidence and mortality, gastric cancer remains the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. A number of environmental factors are correlated with gastric cancer development [2–5]. Additionally, a family history of cancer, especially gastric cancer, is associated with increased risk of developing the disease [6, 7]. It is estimated that approximately 13.5% to 46.4% of gastric cancer patients have a family history of cancer [8–10]. Recently, longer overall survival has been reported in other cancer patients with a family history of cancer [11, 12]. Although some studies have reported the clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric cancer patients with a family history of cancer, these results have been inconsistent [8, 9, 13, 14]. Therefore, the effect of family history of cancer on survival in gastric cancer patients is still unclear. To clarify this question, we conducted this study to evaluate the correlation between family history of cancer and clinicopathologic characteristics and overall survival of gastric cancer patients.

RESULTS

Clinicopathological characteristics

Patients included 1263 males and 542 females (2.3:1) with a mean age of 58 years. There were 339 (18.8%) early gastric cancers and 1466 (81.2%) advanced gastric cancers. Differentiated tumors were observed in 471 (26.1%) patients, and undifferentiated in 1334 (73.9%) patients. 339 (18.8%) were type 0, 9 (0.5%) type I, 502 (27.8%) type II, 879 (48.7%) type III, 76 (4.2%) type IV. Of 1805 patients, 577 (32.0%) had tumors located in the upper third, 298 (16.5%) had tumors in the middle third, 821 (45.5%) had tumors in the lower third of the stomach, and 109 (6.0%) had tumors occupying two-thirds or more of stomach. Lymph node metastasis was observed in 1122 patients (62.2%). The distribution of pathological stage was as follows: 279 (15.5%) patients had stage IA tumors, 216 (12.0%) IB, 186 (10.3%) IIA, 244 (13.5%) IIB, 230 (12.7%) IIIA, 291 (16.1%) IIIB, and 359 (19.9%) IIIC. Patients demographics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient cohort.

| n =1805 | 100% | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1263 | 70.0 |

| Female | 542 | 30.0 |

| Age (yr) | ||

| <60 | 997 | 55.2 |

| ≥60 | 808 | 44.8 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| <5 | 902 | 61.6 |

| ≥5 | 562 | 38.4 |

| Histological type | ||

| Differentiated | 471 | 26.1 |

| Undifferentiated | 1334 | 73.9 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Upper third | 577 | 32.0 |

| Middle third | 298 | 16.5 |

| Lower third | 821 | 45.5 |

| Two-third or more | 109 | 6.0 |

| Borrmann type | ||

| 0 | 339 | 18.8 |

| I | 9 | 0.5 |

| II | 502 | 27.8 |

| III | 879 | 48.7 |

| IV | 76 | 4.2 |

| Vascular tumor emboli | ||

| Yes | 620 | 34.3 |

| No | 1185 | 65.7 |

| Nervous invasion | ||

| Yes | 657 | 36.4 |

| No | 1148 | 63.6 |

| Pathological stage | ||

| IA | 279 | 15.5 |

| IB | 216 | 12.0 |

| IIA | 186 | 10.3 |

| IIB | 244 | 13.5 |

| IIIA | 230 | 12.7 |

| IIIB | 291 | 16.1 |

| IIIC | 359 | 19.9 |

| Family history of cancer | ||

| Positive | 382 | 21.2 |

| Negative | 1423 | 78.8 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 193 | 10.7 |

| No | 1612 | 89.3 |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 127 | 7.0 |

| No | 1678 | 93.0 |

| P21 expression | ||

| Positive | 1134 | 62.8 |

| Negative | 671 | 37.2 |

| P53 expression | ||

| Positive | 1319 | 73.1 |

| Negative | 486 | 26.9 |

| c-myc expression | ||

| Positive | 1138 | 63.0 |

| Negative | 667 | 37.0 |

| EGFR expression | ||

| Positive | 697 | 38.6 |

| Negative | 1108 | 61.4 |

| Neu/Her-2 | ||

| Positive | 43 | 2.4 |

| Negative | 1762 | 97.6 |

Immunohistochemical characteristics

The expression of p21, p53, c-myc, EGFR and Neu/Her-2 was examined by immunohistochemical staining. The location of staining was predominantly in the cell nucleus for p21 and p53, cell cytoplasm for c-myc, cell cytoplasm or membrane for EGFR, and membrane for Neu/Her-2. The positive expression rates of p21, p53, c-myc, EGFR, and Neu/Her-2 were 62.8%, 73.1%, 63.0%, 38.6%, and 2.4%, respectively.

Family history of cancer

Of 1805 patients, 382 (21.2%) had at least one relative with any type of cancer. By cancer type, gastric cancer was the most common and occurred in 190 patients (10.5%), while 192 patients (10.6%) had a family history of other cancers. 348 (19.3%) patients had a family history in first-degree relatives, and 34 (1.9%) in second-degree relatives. In the patients with a family history of gastric cancer, 169 (9.4%) had a family history in first-degree relatives and 21 (1.2%) in second-degree relatives. Data is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Family histories of cancer in gastric cancer patients.

| Family history | No. of patients (1805) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | ||

| Yes | 382 | 21.2 |

| No | 1423 | 78.8 |

| Relatives | ||

| First degree | 348 | 19.3 |

| Second degree | 34 | 1.9 |

| No. of relatives with cancer | ||

| 1 | 258 | 14.3 |

| ≥2 | 124 | 6.9 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Gastric cancer | 190 | 10.5 |

| All other cancers | 192 | 10.6 |

| Gastric cancer | ||

| Yes | 190 | 10.5 |

| No | 1615 | 89.5 |

| Relatives | ||

| First degree | 169 | 9.4 |

| Second degree | 21 | 1.2 |

| No. of relatives with gastric cancer | ||

| 1 | 113 | 6.3 |

| ≥2 | 77 | 4.3 |

| All other cancers without gastric cancer | ||

| Yes | 192 | 10.6 |

| No | 1613 | 89.4 |

| Relatives | ||

| First degree | 179 | 9.9 |

| Second degree | 13 | 0.7 |

| No. of relatives with cancer | ||

| 1 | 145 | 8.0 |

| ≥2 | 47 | 2.6 |

Demographic and clinicopathologic features of PFH

Demographically, patients with a positive family history of cancer were younger than patients without positive family history of cancer. There was no difference in gender distribution between the two groups. In patients with a positive family history of cancer, the proportion of smoking and alcohol use was higher than in patients without family history. Clinicopathologically, significant differences were observed in degree of differentiation, tumor location, tumor size, and p21 expression between the two groups. Patients with a positive family history of cancer had a higher rate of undifferentiated tumors and lower 1/3 tumors, smaller tumors, and a lower rate of p21 expression than in those without a positive family history. Data were shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with positive family history of cancer (PFH) and negative family history of cancer (NFH).

| Variables | PFH n= 382 | NFH n= 1423 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.297 | ||

| Male | 259 | 1004 | |

| Female | 123 | 413 | |

| Age (yr) | 0.0003 | ||

| <60 | 242 | 755 | |

| ≥60 | 140 | 668 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.007 | ||

| <5 | 267 | 889 | |

| ≥5 | 115 | 534 | |

| Histological type | 0.002 | ||

| Differentiated | 76 | 395 | |

| Undifferentiated | 306 | 1028 | |

| Tumor location | 0.021 | ||

| Upper third | 97 | 480 | |

| Middle third | 67 | 231 | |

| Lower third | 192 | 629 | |

| Two-third or more | 26 | 83 | |

| Borrmann type | 0.088 | ||

| 0 | 88 | 251 | |

| I | 3 | 6 | |

| II | 93 | 409 | |

| III | 180 | 699 | |

| IV | 18 | 58 | |

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.483 | ||

| Yes | 137 | 483 | |

| No | 245 | 940 | |

| Nervous invasion | 0.152 | ||

| Yes | 151 | 506 | |

| No | 231 | 917 | |

| Pathological stage | 0.207 | ||

| IA | 73 | 206 | |

| IB | 47 | 169 | |

| IIA | 37 | 149 | |

| IIB | 51 | 193 | |

| IIIA | 47 | 183 | |

| IIIB | 48 | 243 | |

| IIIC | 79 | 280 | |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 123 | |

| No | 312 | 1300 | |

| Drinking | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 41 | 86 | |

| No | 341 | 1337 | |

| P21 expression | 0.012 | ||

| Positive | 219 | 915 | |

| Negative | 163 | 508 | |

| P53 expression | 0.985 | ||

| Positive | 279 | 1040 | |

| Negative | 103 | 383 | |

| c-myc expression | 0.158 | ||

| Positive | 229 | 909 | |

| Negative | 153 | 514 | |

| EGFR expression | 0.066 | ||

| Positive | 132 | 565 | |

| Negative | 250 | 858 | |

| Neu/Her-2 | 0.054 | ||

| Positive | 4 | 39 | |

| Negative | 378 | 1384 |

Univariate analysis

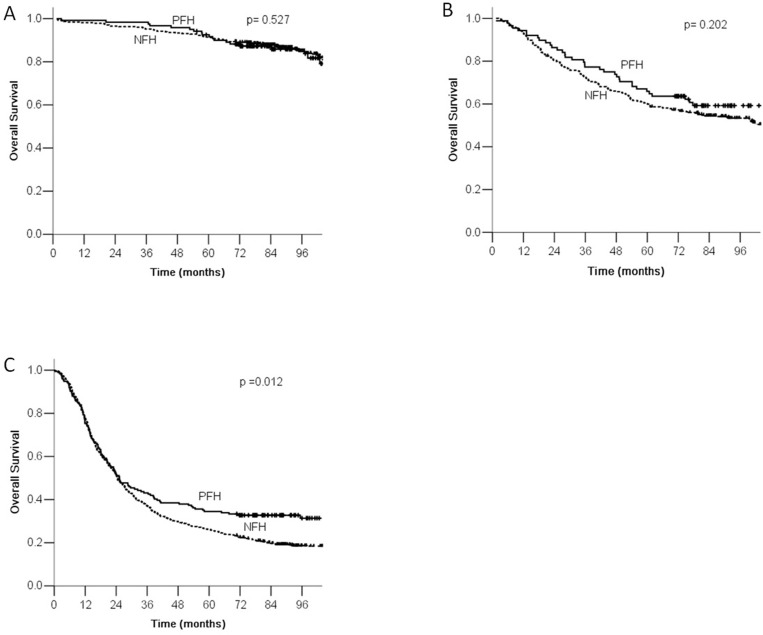

The overall 5-year survival rate was 53% for all patients. The 5-year survival rates of PFH and NFH groups were 60% and 52%, and the difference was statistically significant (Figure 1). Additionally, significant prognostic factors included age, differentiation, vascular tumor emboli, nervous invasion, tumor location, tumor size, Borrmann type, TNM stage, family history of gastric cancer, family history of other cancers, p21 overexpression, Neu/Her-2 overexpression, and EGFR overexpression (Table 4). In the PFH group, vascular tumor emboli, nervous invasion, tumor location, tumor size, Borrmann type, TNM stage, p21 overexpression, and c-myc overexpression were significant prognostic factors for survival (Table 5). In the NFH group, age, differentiation, venous tumor emboli, nervous invasion, tumor location, tumor size, Borrmann type, TNM stage, p21 overexpression, Neu/Her-2 overexpression, and EGFR overexpression were significantly correlated with prognosis (Table 6).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves by family history of cancer.

There were significant differences between PFH and NFH.

Table 4. Univariate analysis of all patients by Kaplan-meier method.

| Variable | n | 5-Year survival rate (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.659 | ||

| Male | 1263 | 52.4 | |

| Female | 542 | 55.4 | |

| Age (yr) | <0.001 | ||

| <60 | 997 | 58.9 | |

| ≥60 | 808 | 46.4 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| <5 | 1156 | 62.3 | |

| ≥5 | 649 | 37.4 | |

| Histological type | <0.001 | ||

| Differentiated | 471 | 62.0 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1334 | 50.3 | |

| Tumor location | <0.001 | ||

| Upper third | 577 | 41.2 | |

| Middle third | 298 | 51.2 | |

| Lower third | 821 | 66.1 | |

| Two-third or more | 109 | 26.2 | |

| Borrmann type | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 339 | 91.3 | |

| I | 9 | 40.3 | |

| II | 502 | 51.1 | |

| III | 879 | 42.8 | |

| IV | 76 | 21.1 | |

| Vascular tumor emboli | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 620 | 31.4 | |

| No | 1185 | 64.8 | |

| Nervous invasion | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 657 | 33.4 | |

| No | 1148 | 64.7 | |

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | ||

| IA | 279 | 93.7 | |

| IB | 216 | 88.6 | |

| IIA | 186 | 66.8 | |

| IIB | 244 | 56.8 | |

| IIIA | 230 | 47.2 | |

| IIIB | 291 | 30.4 | |

| IIIC | 359 | 13.0 | |

| Smoking | 0.061 | ||

| Yes | 193 | 52.5 | |

| No | 1612 | 60.3 | |

| Drinking | 0.240 | ||

| Yes | 127 | 57.9 | |

| No | 1678 | 53.0 | |

| Family history of cancer | 0.001 | ||

| Positive | 382 | 59.8 | |

| Negative | 1423 | 51.6 | |

| Family history of gastric cancer | 0.031 | ||

| Positive | 190 | 54.2 | |

| Negative | 1615 | 43.0 | |

| Family history of other cancers | 0.038 | ||

| Positive | 192 | 54.2 | |

| Negative | 1613 | 43.0 | |

| P21 expression | 0.002 | ||

| Positive | 1134 | 50.5 | |

| Negative | 671 | 58.0 | |

| P53 expression | 0.606 | ||

| Positive | 1319 | 54.0 | |

| Negative | 486 | 51.5 | |

| c-myc expression | 0.333 | ||

| Positive | 1138 | 52.4 | |

| Negative | 667 | 54.8 | |

| EGFR expression | 0.006 | ||

| Positive | 697 | 48.3 | |

| Negative | 1108 | 56.3 | |

| Neu/Her-2 | 0.019 | ||

| Positive | 43 | 30.2 | |

| Negative | 1762 | 53.8 |

Table 5. Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis of patients with PFH.

| Variable | n | 5-Year survival rate (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.540 | ||

| Male | 259 | 57.1 | |

| Female | 123 | 65.8 | |

| Age (yr) | 0.380 | ||

| <60 | 242 | 60.7 | |

| ≥60 | 140 | 58.9 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| <5 | 267 | 67.9 | |

| ≥5 | 115 | 41.3 | |

| Histological type | 0.160 | ||

| Differentiated | 76 | 65.9 | |

| Undifferentiated | 306 | 57.9 | |

| Tumor location | <0.001 | ||

| Upper third | 97 | 50.3 | |

| Middle third | 67 | 61.9 | |

| Lower third | 192 | 68.5 | |

| Two-third or more | 26 | 23.1 | |

| Borrmann type | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 88 | 91.4 | |

| I | 3 | 0.0 | |

| II | 93 | 63.9 | |

| III | 180 | 44.7 | |

| IV | 18 | 33.3 | |

| Vascular tumor emboli | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 137 | 37.6 | |

| No | 245 | 71.5 | |

| Nervous invasion | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 151 | 41.9 | |

| No | 231 | 71.2 | |

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | ||

| IA | 73 | 93.8 | |

| IB | 47 | 88.8 | |

| IIA | 37 | 73.3 | |

| IIB | 51 | 60.8 | |

| IIIA | 47 | 58.7 | |

| IIIB | 48 | 41.7 | |

| IIIC | 79 | 13.8 | |

| Smoking | 0.833 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 57.3 | |

| No | 312 | 60.1 | |

| Drinking | 0.819 | ||

| Yes | 41 | 58.5 | |

| No | 341 | 59.9 | |

| P21 expression | 0.041 | ||

| Positive | 219 | 54.9 | |

| Negative | 163 | 66.8 | |

| P53 expression | 0.535 | ||

| Positive | 279 | 61.1 | |

| Negative | 103 | 55.8 | |

| c-myc expression | 0.017 | ||

| Positive | 229 | 54.8 | |

| Negative | 153 | 66.8 | |

| EGFR expression | 0.196 | ||

| Positive | 132 | 53.0 | |

| Negative | 250 | 63.3 | |

| Neu/Her-2 | 0.545 | ||

| Positive | 4 | 50.0 | |

| Negative | 378 | 60.1 |

Table 6. Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis of patients with NFH.

| Variable | n | 5-Year survival rate (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.939 | ||

| Male | 1004 | 51.2 | |

| Female | 419 | 52.4 | |

| Age (yr) | <0.001 | ||

| <60 | 755 | 58.3 | |

| ≥60 | 668 | 43.8 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| <5 | 889 | 60.5 | |

| ≥5 | 534 | 36.5 | |

| Histological type | <0.001 | ||

| Differentiated | 395 | 60.9 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1028 | 47.8 | |

| Tumor location | <0.001 | ||

| Upper third | 480 | 39.2 | |

| Middle third | 231 | 47.8 | |

| Lower third | 629 | 65.3 | |

| Two-third or more | 83 | 26.7 | |

| Borrmann type | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 251 | 90.9 | |

| I | 6 | 50.0 | |

| II | 409 | 48.0 | |

| III | 699 | 42.1 | |

| IV | 58 | 17.2 | |

| Vascular tumor emboli | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 483 | 29.5 | |

| No | 940 | 62.7 | |

| Nervous invasion | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 506 | 30.6 | |

| No | 917 | 62.9 | |

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | ||

| IA | 206 | 93.4 | |

| IB | 169 | 88.6 | |

| IIA | 149 | 65.2 | |

| IIB | 193 | 55.7 | |

| IIIA | 183 | 43.3 | |

| IIIB | 243 | 28.2 | |

| IIIC | 280 | 12.8 | |

| Smoking | 0.050 | ||

| Yes | 123 | 60.9 | |

| No | 1300 | 50.6 | |

| Drinking | 0.334 | ||

| Yes | 86 | 57.1 | |

| No | 1337 | 51.1 | |

| P21 expression | 0.031 | ||

| Positive | 915 | 49.4 | |

| Negative | 508 | 55.4 | |

| P53 expression | 0.781 | ||

| Positive | 1040 | 52.0 | |

| Negative | 383 | 50.2 | |

| c-myc expression | 0.781 | ||

| Positive | 909 | 51.8 | |

| Negative | 514 | 51.1 | |

| EGFR expression | 0.023 | ||

| Positive | 565 | 47.4 | |

| Negative | 858 | 54.3 | |

| Neu/Her-2 | 0.037 | ||

| Positive | 39 | 28.2 | |

| Negative | 1384 | 52.2 |

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis showed that family history of cancer, age, tumor differentiation, vascular tumor emboli, Borrmann type, tumor size, TNM stage, and p21 overexpression were independent prognostic factors for all patients (Table 7). In the PFH group, TNM stage and c-myc overexpression were significant prognostic factors (Table 8). In the NFH group, age, differentiation, vascular tumor emboli, and TNM stage were independent prognostic factors (Table 9).

Table 7. Multivariate analysis of patients by Cox model.

| Variable | P value | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | 1.327 | 1.170-1.505 |

| Histological type | 0.007 | 1.234 | 1.060-1.437 |

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.005 | 1.225 | 1.065-1.409 |

| Nervous invasion | 0.149 | 1.108 | 0.964-1.273 |

| Tumor location | 0.081 | 0.944 | 0.885-1.007 |

| Borrmann type | 0.041 | 1.093 | 1.004-1.191 |

| Tumor size | 0.035 | 1.149 | 1.010-1.308 |

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | 1.464 | 1.400-1.532 |

| Family history of cancer* | 0.033 | 0.836 | 0.708-0.986 |

| Family history of gastric cancer* | 0.309 | 0.891 | 0.714-1.113 |

| Family history of other cancers* | 0.073 | 0.817 | 0.655-1.019 |

| P21 | 0.045 | 1.146 | 1.003-1.309 |

| EGFR | 0.183 | 1.091 | 0.960-1.240 |

| Neu/Her-2 | 0.173 | 1.287 | 0.895-1.851 |

Only one parameter can be put into Cox proportional hazards model very time.

Table 8. Multivariate analysis of patients with PFH.

| Variable | P value | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.109 | 1.312 | 0.942-1.830 |

| Nervous invasion | 0.506 | 1.120 | 0.802-1.562 |

| Tumor location | 0.404 | 0.934 | 0.796-1.096 |

| Tumor size | 0.165 | 1.253 | 0.911-1.724 |

| Borrmann type | 0.097 | 1.184 | 0.970-1.445 |

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | 1.452 | 1.305-1.617 |

| P21 | 0.094 | 1.307 | 0.955-1.787 |

| c-myc | 0.028 | 1.424 | 1.039-1.953 |

Table 9. Multivariate analysis of patients with NFH.

| Variable | P value | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | 1.393 | 1.212-1.601 |

| Histological type | 0.005 | 1.270 | 1.077-1.499 |

| Vascular tumor emboli | 0.019 | 1.203 | 1.030-1.405 |

| Nervous invasion | 0.182 | 1.110 | 0.952-1.293 |

| Tumor location | 0.115 | 0.944 | 0.880-1.014 |

| Tumor size | 0.085 | 1.133 | 0.983-1.305 |

| Borrmann type | 0.140 | 1.074 | 0.977-1.180 |

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | 1.469 | 1.397-1.544 |

| P21 | 0.171 | 1.108 | 0.957-1.284 |

| EGFR | 0.140 | 1.112 | 0.966-1.280 |

| Neu/Her-2 | 0.188 | 1.287 | 0.884-1.876 |

Comparison of survival according to stage between PFH and NFH groups

According to the AJCC/TNM staging, gastric cancer patients were divided into stage I, stage II, and stage III. According to family history of cancer, each stage was divided into PFH and NFH groups. There was a statistically significant difference in overall survival between the PFH and NFH groups for patients with stage III tumors (P <0.05, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of survival according to tumor stage.

There were significant differences between PFH and NFH according to stage III.

DISCUSSION

Familial aggregation is quite common in all kinds of cancers. In this study, 21.2% of gastric patients had a positive family history of cancer. This is similar to that reported in previous studies [8–10]. The reason for familial aggregation is unclear. It is possible that environmental factors or genetic factors contribute to this. Some studies have shown that environmental factors such as diet or socioeconomic status were significantly associated with risk of family gastric cancer [15, 16]. Additionally, Some studies have reported that microsatellite instability (MSI) was associated with family history of gastric cancer [17, 18]. Lee et al. reported that p53 overexpression may increase familial aggregation of gastric cancer [8]. In the current study, we examined expression of some genes, and we found that p21 expression by tumor cells correlated with family history of gastric cancer. Further study is needed to elucidate the mechanism.

In this study, we found that gastric cancer patients with family history of cancer had different clinicopathological features compared to those without a family history of cancer. Our results showed that patients with a family history of cancer were younger than patients without family history of cancer. However, this result was inconsistent with that reported by a Korean study [9], which found that there was no significant difference in mean ages between familiar gastric cancer and sporadic cancer. It is possible that difference is due to the bias of self-reported family history. Another two recent studies have confirmed our results [19, 20]. Additionally, we found that patients with positive family history of cancer had a higher rate of lower 1/3 tumors. Inoue et al [21] also reported that tumors were more frequently located in the lower and middle part of the stomach in gastric cancer patients with a positive family history. In all, the differences of clinicopathological features and some genes expression between two groups indicated that gastric cancer with positive family history may represent a distinct disease.

Although some studies have reported the effects of a positive family history on the survival of patients with gastric cancer, the results were controversial [8, 9, 13, 14]. These inconsistencies might be due to the adjustment range of confounding variables. Additionally, it might be explained by low statistical power as a result of small-scale sample. In our study, family history of cancer was consistently associated with prognosis in both univariate and multivariate analyses after adjustment for prognostic variables. It is not clear why a family history of cancer increase survival. It is possible that a family history of cancer may heighten awareness of gastric cancer in family members, leading to earlier diagnosis and better prognosis. We found that patients with a positive family history were more likely to have smaller tumor size. However, the current study could not confirm this hypothesis as a result of no information about previous screening. Some studies have shown that patients with a family history of cancer are more likely to undergo cervical cancer and prostate cancer screening [22, 23]. Additionally, health behaviour may also have contributed to the better survival of patients with family history of cancer. Patients with a family history of cancer more likely to have good behavioural habits, like quitting smoking, or healthy dietary habits [24, 25]. Given the fact that smoking and drinking habits are associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer, a reduced incidence of unhealthy behaviour may partly account for improved prognosis. Han et al. reported that proportions of current smokers or drinkers were significantly lower in patients with a family history of cancer[9]. In contrast, we found that proportions of smokers or drinkers were significantly higher in patients with family history, and smoking or drinking did not affect the survival of gastric cancer patients. Therefore, the effect of health behaviour on prognosis needs further investigation. Finally, genetics may also account for the survival differences of gastric cancer patients with a family history. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is detected frequently in gastric cancer. It has been reported that MSI is associated with a family history of gastric cancer and better overall prognosis [17, 18, 26]. In this study, expressions of p21, p53, c-myc, EGFR and Neu/Her-2 were examined by immunohistochemical staining. We found that rate of p21 expression was lower in patients with family history. In addition, multivariate analysis showed that p21 expression was an adverse independent prognostic factor for gastric cancer. These results indicated that low expression of p21 contributed to the good prognosis of gastric cancer patients with family history of cancer. However, the exact mechanism is unclear, and further study is needed.

A limitation of our study is that it has relied on self-reported family history, and the family history information was not confirmed pathologically. However, we confirmed the family history by asking patients' relatives in order to reduce the probability of under-reports or over-reports. Secondly, we did not investigate genetic mutations for MSI or CDH1.

In conclusion, our study showed that the prognosis of gastric cancer patients with a family history of cancer was better than that of patients without a family history. Given the association of p21 expression and family history of cancer, this result may facilitate further development of agents targeting p21 expression and clinical trials evaluating the role of these agent in gastric cancer patients with a family history of cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From 2000 to 2008, 1805 patients with histologically confirmed primary gastric adenocarcinoma underwent curative gastrectomy at the Department of Gastric Cancer and Soft Tissue Sarcoma Surgery, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. Exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) surgery status unknown; (2) vital status unknown; (3) uncompleted pathological data. Data were retrieved from operative and pathological reports. Follow-up data were obtained by phone, outpatient visits and our clinical database. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. Staging was done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging Classification for Carcinoma of the Stomach (Seventh Edition, 2010). Gastrectomy was performed in accordance with the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma.

Immunohistochemical staining

The expression of p21, p53, c-myc, EGFR, and Neu/Her-2 in primary lesions was detected by immunohistochemical staining. All primary antibodies and mouse monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Dako (Hamburg, Germany). The detailed sources, concentrations of antibody and positive site were as follows: anti-p21 (clone SX118), 1:50 dilution, nucleus; anti-p53 (clone DO-7), 1:100 dilution, nucleus; anti-c-myc (clone 9E10), 1:100 dilution, cytoplasm; anti-EGFR (clone E30), 1:50 dilution, cytoplasm or membrane; anti-Neu/Her-2 (clone PN2A), 1:100 dilution, membrane. The staining experiments followed the supplier's instruction. Negative controls were subjected to the same procedure except that the first antibody was replaced by PBS.

Immunohistochemical staining scores

All slides were evaluated by pathologists without knowledge of patients' clinical data. The percentage of immunoreactive cells was graded on a scale of 0 to 4: no staining was scored as 0, 1-10% of cells stained scored as 1, 11-50% as 2, 51-80% as 3, and 81-100% as 4. The staining intensities were graded from 0 to 3: 0 was defined as negative, 1 as weak, 2 as moderated, and 3 as strong, respectively. An IHS score of 9-12 was considered as strong immunoreactivity (+++), 5-8 as moderate (++), 1-4 as weak (+), and 0 as negative (−). On the final analysis, the cases with a score of less than 1 were considered as negative, and ≥ 1 was regarded as positive. These criteria were based on our previously published results [27].

Family history evaluation

Family history of cancer was reviewed from the patient interview record. A positive family history of cancer was defined as a history of cancer within second-degree relatives. First-degree relatives were defined as parents, siblings, or offspring, and second-degree relatives were defined as aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, or grandparents.

Follow-up

Follow-up of all patients was carried out according to our hospital's standard protocol (every three months for at least 2 years, every six months for the next 3 years, and after 5 years every 12 months for life). The check-up items included physical examination, tumor-marker examination, ultrasound, chest radiography, computed tomographic scan, and endoscopic examination. The median follow-up time was 72 months for all patients.

Statistical analysis

The patients' features and clinicopathological characteristics were analyzed using the X2 test for categorical variables. Five-year survival rate was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences between survival curves were examined with the log-rank test. Independent prognostic factors were examined by the multivariate survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model. The accepted level of significance was P <0.05. Statistical analyses and graphics were performed using the SPSS 13.0 statistical package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ben Liotta for editing our manuscript's English language style, and the patients for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

GRANT SUPPORT

This research is supported by grants from the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology Funds (Contract grant numbers: 14ZR1407800), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502027). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen MJ, Chiou YY, Wu DC, Wu SL. Lifestyle habits and gastric cancer in a hospital-based case-control study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3242–3249. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung NY, Choi KS, Park EC, Park K, Lee SY, Lee AK, Choi IJ, Jung KW, Won YJ, Shin HR. Smoking, alcohol and gastric cancer risk in Korean men: The National Health Insurance Corporation Study. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:700–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peleteiro B, Lopes C, Figueiredo C, Lunet N. Salt intake and gastric cancer risk according to Helicobacter pylori infection, smoking, tumor site and histological type. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:198–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Gentile A. Family history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:50–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<50::aid-cncr2820700109>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaghoobi M, Bijarchi R, Narod S. Family history and the risk of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:237–242. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WJ, Hong RL, Lai IR, Chen CN, Lee PH, Huang MT. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognoses of gastric cancer in patients with a positive familial history of cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:30–33. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han MA, Oh MG, Choi IJ, Park SR, Ryu KW, Nam BH, Cho SJ, Kim CG, Lee JH, Kim YW. Association of family history with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:701–708. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki K, Kanemitsu K, Yasuda T, Kamigaki T, Kuroda D, Kuroda Y. Family history of cancer in Japanese gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:173–175. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan JA, Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Thomas J, Schaefer P, Whittom R, Hantel A, Goldberg RM, Warren RS, Bertagnolli M, Fuchs CS. Association of family history with cancer recurrence and survival among patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2008;299:2515–2523. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thalib L, Wedren S, Granath F, Adami HO, Rydh B, Magnusson C, Hall P. Breast cancer prognosis in relation to family history of breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1378–1381. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yatsuya H, Toyoshima H, Mizoue T, Kondo T, Tamakoshi K, Hori Y, Tokui N, Hoshiyama Y, Kikuchi S, Sakata K, Hayakawa N, Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y, Yoshimura T. Family history and the risk of stomach cancer death in Japan: differences by age and gender. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:688–694. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Y, Hu N, Han X, Giffen C, Ding T, Goldstein A, Taylor P. Family history of cancer and risk for esophageal and gastric cancer in Shanxi, China. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldas C, Carneiro F, Lynch HT, Yokota J, Wiesner GL, Powell SM, Lewis FR, Huntsman DG, Pharoah PD, Jankowski JA, MacLeod P, Vogelsang H, Keller G, et al. Familiar gastric cancer: overview and guidelines for management. J Med Genet. 1999;36:873–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WJ, Lin JT, Lee WC, Shun CT, Hong RL, Cheng AL, Lee PH, Wei TC, Chen KM. Clinicopathologic characteristics of Helicobacter Pylori seropositive gastric adenocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:203–207. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palli D, Russo A, Ottini L, Masala G, Saieva C, Amorosi A, Cama A, D'Amico C, Falchetti M, Palmirotta R, Decarli A, Mariani Costantini R, Fraumeni JF., Jr Red meat, family history, and increased risk of gastric cancer with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5415–5419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedrazzani C, Corso G, Velho S, Leite M, Pascale V, Bettarini F, Marrelli D, Seruca R, Roviello F. Evidence of tumor microsatellite instability in gastric cancer with familiar aggregation. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s10689-008-9231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandt A, Bermejo JL, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Age of onset in familial cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:2084–2088. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moolgavkar SH, Luebeck EG. Multistage carcinogenesis: Population-based model for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:610–618. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue M, Tajima K, Yamamura Y, Hamajima N, Hirose K, Kodera Y, Kito T, Tominaga S. Family history and subsite of gastric cancer: data from a case-referent study in Japan. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:801–805. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980610)76:6<801::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams KP, Reiter P, Mabiso A, Maurer J, Paskett E. Family history of cancer predicts Papanicolaou screening behavior for African American and white women. Cancer. 2009;115:179–189. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallner LP, Sarma AV, Lieber MM, St Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Gowan ME, Jacobsen SJ. Psychosocial factors associated with an increased frequency of prostate cancer screening in men ages 40 to 79 years: The Olmsted County Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3588–3592. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humpel N, Magee C, Jones SC. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on the health behaviors of cancer survivors and their family and friends. Support Cancer Cancer. 2007;15:621–630. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson F, Wileyto EP, Segal J, Kurz J, Glanz K, Hanlon A. Intention to quit smoking: Role of personal and family member cancer diagnosis. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:792. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corso G, Pedrazzani C, Marrelli D, Pascale V, Pinto E, Roviello F. Correlation of microsatellite instability at multiple loci with long-term survival in advanced gastric carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2009;144:722–727. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Cai H, Huang H, Long Z, Shi Y, Wang Y. The prognostic significance of apoptosis-related biological markers in Chinese gastric cancer patients. PloS One. 2011;6:e29670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]