Abstract

Context:

Factors that regulate physiological feedback by pulses of glucocorticoids on the hypothalamic-pituitary unit are sparsely defined in humans in relation to gluco- or mineralocorticoid receptor pathways, gender, age, and the sex steroid milieu.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to test (the clinical hypothesis) that glucocorticoid (GR) and mineralocorticoid (MR) receptor-selective mechanisms differentially govern pulsatile cortisol-dependent negative feedback on ACTH output (by the hypothalamo-pituitary unit) in men and women studied under experimentally defined T and estradiol depletion and repletion, respectively.

Setting:

The study was conducted at the Mayo Center for Translational Science Activities.

Subjects:

Healthy middle-aged men (n = 16) and women (n = 25) participated in the study.

Interventions:

This was a randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo- and saline-controlled study of pulsatile cortisol infusions in low cortisol-clamped volunteers with and without eplerenone (MR blocker) and mifepristone (GR blocker) administration under a low and normal T and estradiol clamp. During frequent sampling, a bolus of CRH-arginine vasopressin was infused to assess corticotrope responsiveness.

Analytical Methods and Outcomes:

Deconvolution and approximate entropy of ACTH profiles were measured.

Results:

Infusion of cortisol (but not saline) pulses diminished ACTH secretion. The GR antagonist, mifepristone, interfered with negative feedback on both ACTH burst mass and secretion regularity. Eplerenone, an MR antagonist, exerted no detectable effect on the same parameters. Despite feedback imposition, CRH-arginine vasopressin-stimulated ACTH secretion was also increased by mifepristone and not by eplerenone. Withdrawal vs addback of sex steroids had no effect on ACTH secretion parameters. Nonetheless, ACTH secretion was greater (P = .006) and more regular (P = .004) in men than women.

Conclusion:

Pulsatile cortisol feedback on ACTH secretion in this paradigm is mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor, in part acting at the level of the pituitary, and influenced by sex.

Healthy adults undergoing pulsatile iv cortisol clamp manifest strong gender differences in feedback control of ACTH secretion, which are not accounted for by the short-term sex-steroid milieu per se.

The stress-responsive hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis constitutes an interactive ensemble of central neural, anterior hypophysial and adrenal-cortical regulatory sites (1). Blood-borne effectors mediate adaptive responses via modulating time-delayed (unobserved) neurotransmitter inputs from the cerebral cortex, hippocampo-limbic system, and hypothalamus, which stimulate or inhibit the burst-like secretion of paraventricular-nucleus CRH and arginine vasopressin (AVP) (2–5). CRH and AVP pulses singly and synergistically drive the exocytotic discharge of ACTH secretory granules and promote the de novo biosynthesis of ACTH precursor proteins in corticotrope cells (6). Pulsatile ACTH concentrations stimulate the pulsatile secretion of cortisol. Pulses of cortisol appear to restrain ACTH secretion by both neuronal and pituitary mechanisms, which include nuclear glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors (7, 8).

Earlier clinical investigations have examined stress-adaptive ACTH responses in pathophysiological contexts, such as chronic alcoholism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, fasting, insulin-induced hypoglycemia, thyroid failure, growth disorders, Cushing's disease, and glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance (9–12). Other studies have focused on healthy individuals, suggesting potential gender distinctions in ACTH-adrenal interactions (13). Sex differences are well established in the rodent but are not so well studied in the human (14). The issue is germane because numerous conditions, such as puberty and aging, are marked by relative repletion and depletion, respectively, of both androgen and estrogen (15, 16).

The primary thesis of this investigation is that regulatory mechanisms mediate adaptive neuroendocrine control, in part, by modulating negative feedback dynamics. Understanding this fundamental regulatory mechanism is important in the stress-adaptive CRH-AVP-ACTH-glucocorticoid axis, which is required for health and longevity.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The protocol was approved by Mayo Institutional Review Board and was reviewed by the Food and Drug Administration for off-label use of ketoconazole (KTCZ), eplerenone, mifepristone, and iv cortisol. Witnessed voluntary written consent was obtained before study enrollment. Participants maintained conventional work and sleeping patterns and reported no recent (within 10 d) transmeridian travel, significant weight loss or gain, intercurrent psychosocial stress, substance abuse, neuropsychiatric illness, or systemic disease. A complete medical history, physical examination, and screening tests of hematological, renal, hepatic, metabolic, and endocrine function were normal. The demographic characteristics of the subjects are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data of the Healthy Volunteers

| Women |

Men |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 (+) | E2 (−) | T (+) | T (−) | |

| Subjects, n | 14 | 11 | 8 | 8 |

| Age, y | 47.6 ± 3.5 | 51.5 ± 3.5 | 36.1 ± 2.9 | 40.7 ± 4.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.5 ± 0.9 | 25.1 ± 0.9 | 25.7 ± 1.1 | 27.3 ± 1.4 |

| TSH, mU/L | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.5 |

| E2, pg/mL | 80 ± 24 | 60 ± 28 | 19 ± 1.7 | 19 ± 1.7 |

| T, ng/dL | 19.1 ± 1.1 | 18.4 ± 2.5 | 460 ± 54 | 450 ± 58 |

| Cortisol, μg/dL | 12.8 ± 1.1 | 13.1 ± 0.8 | 13.3 ± 1.2 | 13.3 ± 1.2 |

| Visceral fat, mm2 | 97 ± 14 | 80 ± 11 | 108 ± 2 | 153 ± 33 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. No statistical significant differences in basal levels between subjects randomized to receive sex steroids and those who did not receive replacement were found with the unpaired Student's t test.

Study design

This was a prospectively randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in 16 men and 25 women with allowable ages of 20–75 years. Each subject received 3.75 mg im leuprolide twice, 2 weeks apart, to induce hypogonadism followed by either sex-steroid or no replacement starting on the day of the second leuprolide injection (called d 1). Sex steroid repletion schedules comprised 1) in men, daily transdermal T gel (7.5 g of 1% hydroalcohol gel of which 10% is absorbed) or no T (no placebo gel available); and 2) in women, daily transdermal estradiol patch 0.10 mg/d independent of age or no intervention. Twelve women were postmenopausal.

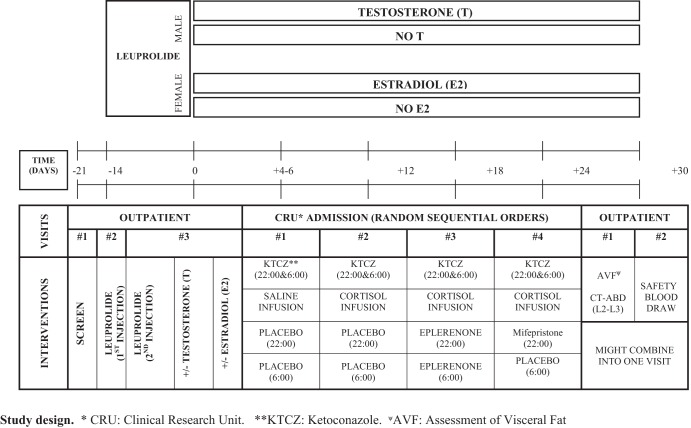

Infusion protocol

Admissions to the clinical research unit (CRU) for infusion/sampling sessions were scheduled at least 4–6 days after beginning sex steroid addback and 4–6 days apart in a within-subject, randomized, crossover design. Volunteers were admitted the evening before the study. Each subject completed four study sessions of repetitive blood sampling every 10 minutes for 10 hours, starting at 2:00 am. The adrenal-blocking regimen comprised oral administration of KTCZ in all four of the CRU sessions. Male subjects received 800 mg at 10:00 pm and 300 mg at 6:00 am, and female subjects received 600 mg at 10:00 pm followed by 200 mg at 6:00 am. The mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) blocking regimens consisted of oral administration of eplerenone and RU-486 (mifepristone), respectively. Subjects received eplerenone 50 mg at 10:00 pm and 50 mg at 6:00 am during one randomized visit. GR blockade was achieved by administering one dose of RU-486 400 mg at 10:00 pm during another randomized visit. An oral placebo was given at 10:00 pm and/or 6:00 am in the other study sessions. The doses of eplerenone and RU-486 were selected based on Food and Drug Administration-reviewed safety data (17, 18). The overall format is schematized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of overall study design. See Materials and Methods for full details. Abbreviations are defined in text.

All four CRU interventions described above were accompanied by pulsatile iv infusion of normal saline (low cortisol clamp) or soluble hydrocortisone hemisuccinate (Solucortef) (pulsatile cortisol clamp) over 12 hours (10:00 pm to 10:00 am) at the young-adult cortisol production rate of 0.525 mg/m2 · h (6.3 mg/m2 per 12 h) (19). The total dose was divided into nine identical iv pulses each of 0.70 mg/m2 in saline infused over 8 minutes and 90 minutes apart (starting at 10:00 pm and ending at 10:00 am. This schedule enforces an eucortisolemic clamp. Human CRH (0.67 μg/kg; Bachem Pharmaceuticals) and AVP (0.67 IU; Parke-Davis, sold as aqueous pitressin 20 U/mL) was administered iv over 1 minute at 10:00 am to assess corticotrope responsiveness.

The 10-minute sampling frequency of ACTH is required for estimating secretion accurately, given the plasma ACTH half-life of 15–30 minutes and the fact that 50% of ACTH release within a burst occurs over 10–12 minutes (see Analytical Methods, below).

For safety reasons, hydrocortisone 25 mg iv was administered at the completion at each of the four inpatient visits.

Mifepristone was obtained from Athenium Inc. Eplerenone and KTCZ were purchased from commercially available sources. To maintain blindness, mifepristone (RU-486) and eplerenone were overencapsulated (blinded) by the Mayo inpatient pharmacy.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were acute or chronic systemic diseases, HIV positivity by medical history, anemia, endocrine disorders (except hypothyroid subjects who were biochemically euthyroid on replacement), psychiatric illness, alcohol or drug abuse, prostatic disease, deep-venous or arterial thromboses; cancer of any type (except localized basal or squamous cell cancer treated surgically without recurrence); allergy to medications used in the study, significant recent weight change (loss/gain of 6 or more pounds over 6 wk), transmeridian travel (exceeding three time zones within the preceding week), systemic drugs (including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and diuretics), abnormal renal, hepatic, or hematologic function, concomitant sex hormone replacement, pregnancy or lactation, and unwillingness to provide written informed consent.

Precautions

Volunteers underwent outpatient screening by way of medical history, physical examination, and biochemical tests. Pregnancy testing was performed within 48 hours of starting each phase of the study.

Blood sampling, drug administration, and cortisol infusion were carried out in the CRU under expert nursing care. Hemoglobin values of 11 g/dL or greater in women and 12 g/dL or greater in men were required. Women with a baseline hemoglobin of 11–11.5 g/dL had documented normal serum ferritin (11–307 μg/L). No other blood donation was allowed immediately before, concurrently, or for 2 months after the study. Subjects aged 50 years and older had an electrocardiogram to exclude myocardial ischemia. Women were required to stop any hormone use at least 3 weeks before the first leuprolide injection. Participants were not to drink alcohol for 48 hours before and during the study. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (10 mg) was administered for 12 days at study completion in accordance with good clinical practice in women with an intact uterus.

Assays

Plasma ACTH was assayed in each 10-minute sample via sensitive and specific, solid-phase immunochemiluminescent assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics). The detection threshold was 5 ng/L (divided by 4.5 for picomoles per liter). Intraassay coefficients of variation were 6.4%, 2.7%, and 3.2% at 5.7, 28, and 402 ng/L, respectively. Cortisol was assayed via competitive binding immunoenzymatic assay (Beckman Coulter). The detection limit was 0.4 μg/dL and intraassay coefficients of variations were 13%, 9.4%, and 6.6% at 1.6, 2.8, and 30 μg/dL, respectively. T, estradiol, and estrone were assayed by mass spectrometry as described (20, 21). Screening biochemical tests were performed by the Mayo Medical Laboratory.

Secondary analyses

The 10-hour, 10-minute sampled, plasma ACTH concentration profiles were dissected into an underlying train of (generalized γ-approximated) secretory bursts of individual mass and random effects based on a priori identification of conditional pulse locations, concurrent low-basal (time-invariant) secretion, and biexponential decay (fixed first component for rapid diffusion and advection and second component for delayed metabolic elimination), using a validated variable waveform deconvolution technique. The analysis implements a modified Matlab-based, adaptive-mesh, multiparameter-search algorithm recently validated. Across the potential pulse-time sets, final model selection is via the Akaike information criterion (22).

Approximate entropy

Adaptive ensemble (network-like) control of ACTH release patterns was appraised via the approximate entropy (ApEn) statistic (23). ApEn is a recently validated pattern-dependent regularity measure, which serves as a sensitive (>90%) and specific (>95%) discriminative metric of interactive complexity (number of connections) and strength (dose response interface properties) in various interlinked (parameter coupled) systems. The statistic is calculated on a time series as a single, finite, positive, real number (between 0 and 2.3 in base 10 data). Technically, ApEn is defined as the (negative logarithm of the) summed probabilities that data patterns of vector (window) length m in a numerical sequence of length N (measurements) recur upon next (m + 1) incremental comparison within a threshold (tolerance) range r (normalized to 20% of the overall series SD, as validated for neurohormone data [24]). ApEn provides a model-free and scale-invariant statistical estimate of relative stochastic and deterministic control of time-series substructure and therefore is thematically distinct from but complementary to deconvolution analysis (above).

Visceral fat mass

To assess potential associations between abdominal visceral fat and cortisol feedback on ACTH release, intraabdominal visceral fat mass was estimated by single-slice abdominal computed tomography scan at the L2-L3 level at the end of the study.

Statistics

The primary statistically powered end point was the model-free, first 8-hour (of 10 h) mean plasma ACTH concentration, determined from 49 serial measurements at pseudosteady state (above). The last 2-hour (of 10 h) sampling was analyzed to evaluate pituitary ACTH responsiveness. Secondary mechanistic outcomes were ACTH secretory-burst mass (analytical integral of reconstructed waveform), secretory-burst shape (generalized γ-density), and burst regularity (γ of Weibull) as well as frequency ([lamdba] of Weibull) (events/8 h), and ApEn (a sensitive measure of feedback control).

There are three a priori clinical hypotheses of special conceptual significance within gender, tested by contrasting responses to the deplete vs replete sex-steroid milieu. Specific postulates were that exposure to the sex-steroid deplete milieu vs clamped T (in men) or estradiol (E2) (in women) to determine the mean ACTH concentration sustained under the following: 1) the hypo- vs eucortisolemic clamps; 2) MR blockade; and 3) GR blockade. The clinical and theoretical independence of these postulates obviates post hoc statistical penalty of individual P values (25), following an unpaired Student's t tests of the logarithm of 8-hour mean ACTH concentrations in men and women separately. Data were analyzed on the logarithmic scale to accommodate asymptotic ACTH secretory responses to feedback manipulation (24).

The results of the deconvolution analysis and ApEn were analyzed with generalized linear model (GLM) comparable with a three-way ANOVA for repeated measures with gender (two factors) and sex-steroid or placebo (two factors) administration as categorical variables. Linear regression was performed to test for possible relations between visceral fat mass or sex steroids and main parameters of deconvolution and ApEn. The calculations were performed with Systat 13 (Systat Software, Inc) and Matlab 8.6 (The MathWorks, Inc). P < .05 was construed as significant for the overall study.

Results

All subjects completed the studies and no adverse events were noted. E2 concentrations in women during the infusion studies were (mean and range) 3.2 (1.1–20) pg/ml in sex steroid-deplete women and 189 (81–337) pg/mL in E2-replete women. In men, T concentrations were 42 (37–93) ng/dL in deplete subjects and 550 (238–870) ng/dL in replete subjects. In the first part of the study, we investigated whether sex hormone addback had an influence on mean (and integrated areas of) plasma ACTH concentrations during the 8 hours of sampling before and after the 2 hours of sampling injection of CRH-AVP. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 show no differences in ACTH secretion between subjects who received sex steroid addback and those who did not (values between P.= 12 and P = .73).

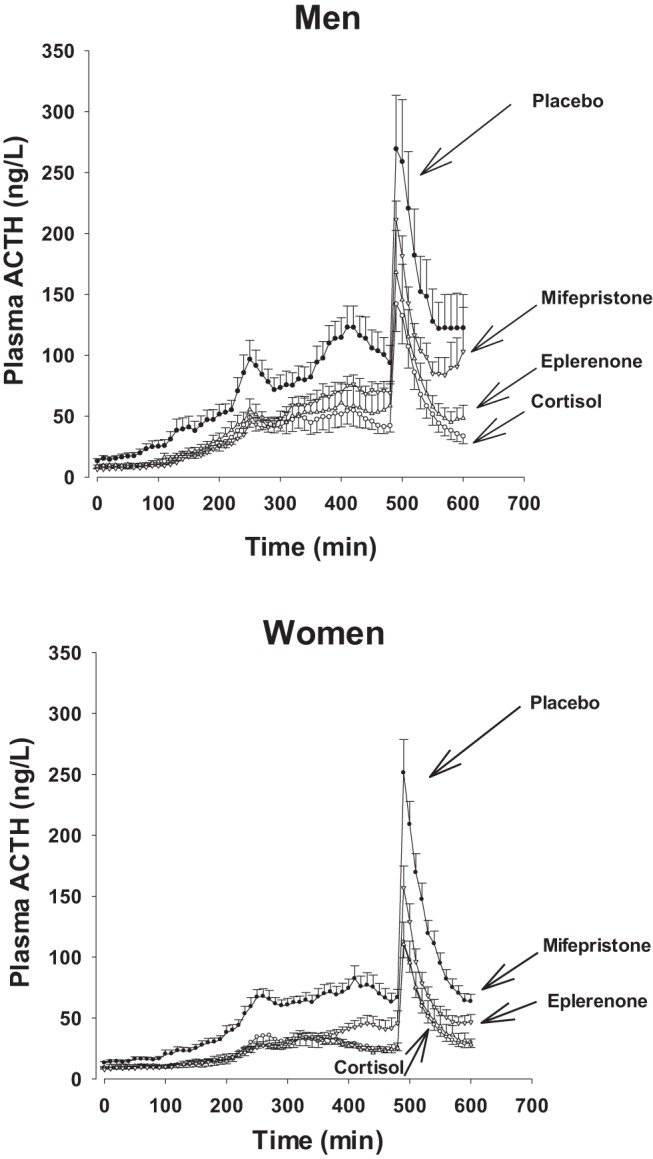

Mean plasma ACTH concentrations during the four different infusion protocols are plotted separately for men and women in Figure 2. ACTH was higher in men than women in all infusion protocols. The profiles illustrate increased ACTH levels in the cortisol-deficient state during the 8-hour sampling before and 2-hour sampling after administration of CRH-AVP. During pulsatile infusion of cortisol (in the three different experiments), plasma ACTH concentrations decreased clearly but remained significantly higher (failed to suppress fully) when mifepristone was administered.

Figure 2.

Plasma ACTH concentration profiles in healthy men and women. All subjects were treated with ketoconazole and received either saline (placebo) or pulsed cortisol infusions. Sequential cortisol or placebo pulses each of 8 minutes of duration were injected at 90-minute intervals, overnight for none pulses in total, during exposure to oral placebo or eplenerone or mifepristone. After 8 hours of 10 minutes of blood sampling, an injection of CRH/AVP was given and sampling continued for 2 more hours. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

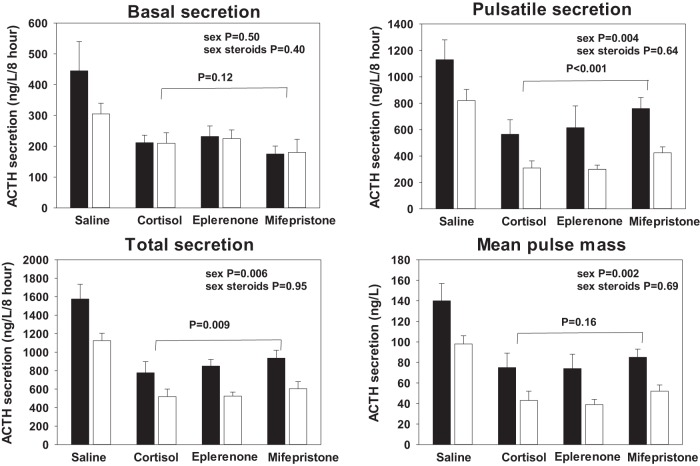

Parameters of deconvolution analysis of ACTH profiles over the first 8 hours of pulsatile cortisol or saline infusions are shown in Supplemental Tables 3–5. The detailed results of the GLM of basal, pulsatile, and total ACTH secretion are listed in the accompanying Supplemental Table 4 and graphically illustrated in Figure 3. Under KTCZ administration and saline infusion, ACTH secretion was enhanced. In contrast, pulsatile cortisol infusion diminished all three of the basal, pulsatile, and total ACTH secretion (P < .0001). These inhibitory effects were not altered by sex hormone addback. As found by the model-free approach (above), gender was an important determinant of pulsatile (and total) but not basal (nonpulsatile). The values for basal, pulsatile, and total ACTH secretion are P = .50, P = .004, and P = .006, respectively. Addition of mifepristone, but not eplerenone, during pulsatile cortisol feedback caused a significant increase of pulsatile (and total) ACTH secretion compared with the placebo orally (P < .001 and P = .009, respectively, Figure 3). Other parameters of the deconvolution analysis, eg, pulse frequency, burst mode (time to maximal hormone secretion), slow component of the hormone half-life, and Weibull-γ (measure of pulse regularity) did not change in the different experiments (GLM contrast values were between P = .20 and P = .60).

Figure 3.

ACTH secretion parameters quantified by deconvolution of 8-hour plasma ACTH profiles. Black bars represent men and open bars women. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Overall significance between the four infusion experiments by GLM was P < .0001 in all four panels. In the unrestrained state (ketoconazole and saline infusion only), ACTH secretion was larger than in the three other conditions in which cortisol was infused. ACTH secretion is larger in men than in women, except for basal (nonpulsatile) ACTH secretion. Individual P values are shown in the panels. Treatment with sex steroids had no effect. Contrasts between cortisol infusion alone and cortisol infusion together with mifepristone are indicated by the horizontal lines.

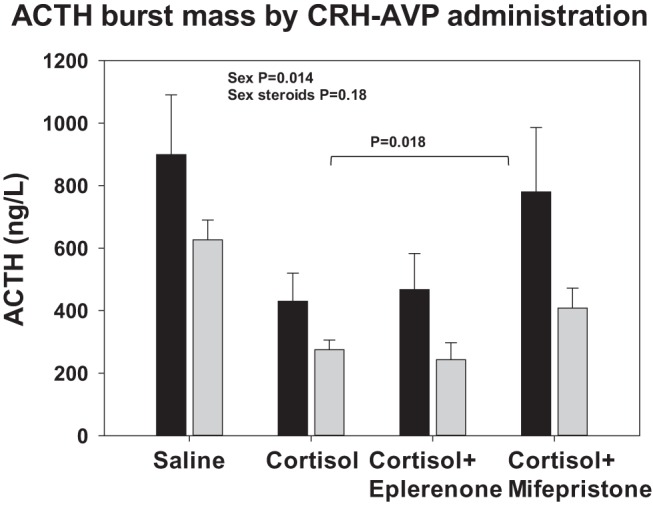

Figure 4 shows the effect of CRH-AVP administration on ACTH secretory-burst mass. Pulsatile cortisol administration every 90 minutes diminished the response to CRH-AVP in all experiments (P < .0001), without modification by gender or sex steroid addback (P = .48 and P = .13, respectively). Overall ACTH secretion was higher in men than women (P = .014) but not altered by sex steroid replacement (P = .18). Administration of mifepristone yielded partial escape of ACTH secretion under pulsatile cortisol feedback compatible with (partial) blocking of the GR (P = .018).

Figure 4.

ACTH secretory-burst mass calculated by deconvolution analysis of 2-hour ACTH time series observed after injection of CRH/AVP. Black bars represent men and gray bars, women. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Overall GLM significance is P < .0001. Selected contrasts between different infusion protocols are as follows: saline vs cortisol and cortisol with eplerenone, P < .0001; cortisol vs cortisol with mifepristone, P = .018; and cortisol vs cortisol with eplerenone, P = .92. ACTH secretion was larger in men than women, but treatment with sex steroids had no significant effects (see inserted text in the figure).

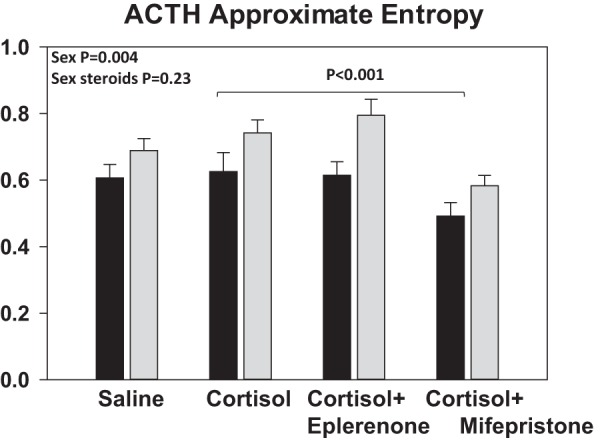

Results of the ACTH ApEn are displayed in the upper panel of Figure 5. Among the four experiments, significant ApEn differences emerged (within groups P < .0001), caused by lower ApEn during GR block by mifepristone (vs oral placebo, P < .001). Cortisol vs saline infusions per se did not increase ApEn, and there were no effects of sex hormone replacement (P = .44). Gender had a marginal effect (P = .035). ApEn was consistently higher in women than in men (P = .004).

Figure 5.

ACTH ApEn, a measure of feedback differences. Black bars represent men and gray bars, women. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Overall GLM significance is P < .0001. ApEn of saline, cortisol + placebo, and cortisol + eplerenone did not differ (P = .17). Addition of mifepristone caused a significant decrease in ACTH ApEn compared with placebo (P < .001), indicating more orderly, less irregular, ACTH secretion patterns. ApEn was larger in women than men in all four infusion sessions (P = .004), signifying greater process randomness in the regulation of ACTH secretion in women.

There were no significant linear relations between logarithmically transformed pulsatile ACTH secretion and T in men or E2 in women or visceral fat in either gender.

Discussion

This study was designed to explore the effects of pulsatile infusions of physiological amounts of cortisol on endogenously driven and exogenous CRH-AVP-stimulated ACTH secretion under MR or GR blockade in both sexes in a sex hormone-deplete or -replete milieu. We could reduce interindividual differences in the sex hormone milieu by inducing hypogonadism with leuprolide and then adding back E2 or T vs placebo in women and men, respectively. Hormone substitution resulted in normal young adult values in replete subjects, whereas low levels were present in the leuprolide-suppressed subjects. Unexpectedly, sex hormones did not influence ACTH levels, within gender, whether in the unstimulated 8-hour sampling phase or after enhancing ACTH secretion by CRH-AVP injection in any of the four separate feedback settings. Experimental data, mainly obtained in (female) rats, have revealed amplification and prolongation of ACTH and corticosterone levels after the application of stressors, together with a decrease in hippocampal MR capacity in E2-treated ovariectomized rats compared with controls (26–28). Human studies of this subject are rare. Recently a partially comparable study showed an amplifying effect of estradiol on suppression of ACTH secretion by cortisol's negative feedback, thus resulting in diminished ACTH levels with no effect of T (29). In the present study, we found no significant effect on ACTH feedback by either E2 or T. Essentially, parts of the two studies are comparable, including the age distribution, the KTCZ dosing, and the cortisol injection schedule. However, in the earlier study, persistence of feedback was tested after stopping the infusion of cortisol, viz, in the ACTH recovery phase. Also, in the present study, E2 concentrations were almost 2 times higher (189 pg/mL vs 92 pg/mL). In contrast, corticosterone and ACTH were positively related to E2 and negatively to T in the rat, although the exact dose responses of E2 and T's effects are not known (26). Thus, sex steroid dose-response studies will be ultimately required to elucidate further aspects of possible gonadal steroid effects in humans.

In the second part of the study, we applied deconvolution analysis to quantify underlying ACTH secretion and half-life. Feedback strongly regulated pulsatile ACTH secretion via ACTH burst mass and therefore also total ACTH secretion. There were no effects on estimated ACTH half-life, basal (nonpulsatile) ACTH secretion, burst frequency, secretory-burst mode (time needed to reach maximal secretion, and thus burst shape), or pulsing regularity. Although quite different, sex hormone environments did not alter endogenous or CRH-AVP enhanced ACTH secretion. Rather, gender per se consistently exerted a significant effect, with greater ACTH secretion in men than women. This confirms our earlier report (29). The overall data raise the possibility of a gonadal sex- rather than a sex hormone-dependent explanation for the adult differences. More likely, some degree of long-term sex imprinting occurs at or after puberty. In any circumstance, when viewed as percentage change in total ACTH secretion, cortisol's feedback effects was similar extent in men and women, viz, 51% and 46%, respectively. The degree to which these strong effects are due to genomic and nongenomic effects of cortisol in humans is not known (30–32).

A third question was which receptors are involved in the feedback of cortisol on ACTH secretion within the physiological range. Whereas the time-dependent variability of ACTH and hence adrenal glucocorticoid secretion is dictated by physiological CRH and AVP drive, feedback by cortisol (or corticosterone in rats and mice) occurs at the levels of the pituitary gland (corticotropes), the hypothalamus (paraventricular nuclei), and the corticolimbic areas to a significant degree by (nuclear) MR and GR having different distributions and ligand affinities (33). In the present pulsatile cortisol-feedback paradigm, suppression of ACTH was blocked in part by a GR but not MR antagonist. In view of the relatively short half-life of eplerenone of 4–6 hours, this drug was dosed two times. Blocking of the MR might theoretically increase ACTH secretion, but that was not observed here, neither before nor after CRH-AVP stimulation. This finding is in accordance with a randomized study in which patients with mild cardiac failure received spironolactone, a less selective MR blocking agent binding also the androgen and progesterone receptors, or eplerenone for 4 months (34). Cortisol levels increased from 11.3 to 14.7 μg/dL in spironolactone-treated patients but remained unchanged in eplerenone-treated patients. Comparable findings were observed in young healthy men (35) and in the rat (36). In a study by Russell et al (32) of 36 healthy men, administration of prednisolone, a mixed glucocorticoid/mineralocorticoid agonist, rapidly suppressed (within 30 min) plasma ACTH and serum cortisol levels. Feedback was not counteracted by MR blockade with spironolactone but was by GR blockade with mifepristone. The MR binding affinity of spironolactone to MR is much stronger than that of eplerenone, despite the latter's markedly superior specificity (37). Consequently, we cannot fully rule out the possibility that the MR antagonist dose used in the present study was insufficiently high to demonstrate effects. However, beneficial antihypertensive effects are obtained by half the dose used in this study (34). The steep rise in ACTH after AVP-CRH, and not diminished by eplerenone, indicates that the MR in corticotrope is not involved in the feedback under the prevailing experimental conditions.

This study clearly demonstrates pulsatile cortisol's feedback signaling via GR, to the degree that mifepristone is specific in this regard. In the face of marked pulsatile cortisol feedback on ACTH secretion (about 50% inhibition), the GR antagonist achieved about 30% relief or rescue from suppression. Disinhibition was evident whether or not exogenous CRH/AVP was infused, indicating that the observed ACTH increase was mediated by the pituitary GR. Concomitant suppression of hypothalamic CRH and/or AVP by cortisol pulses cannot be assessed directly in this study. Nonetheless, the extent of ACTH's rescue from cortisol feedback was similar in percentage for endogenously driven and exogenously stimulated ACTH secretion. This outcome points to significant corticotrope effects.

ApEn, a metric for secretion regularity and changing feed-forward and feedback strength, decreased during GR blockade. This indicates a more orderly ACTH release process (23). A comparable ApEn change occurs during unrestrained ACTH secretion in healthy adults treated with metyrapone or ketoconazole (38). A mechanistic explanation for increased ACTH secretory regularity when negative feedback is muted might involve comodulation by somatostatin or other hypothalamic factors (38). Glucose ingestion, thought to elevate somatostatin, also increases pulsatile ACTH and cortisol secretion, and decreases ACTH ApEn (39). In the present study, there was a clear gender difference in ACTH ApEn in all four separate interventions. However, in healthy subjects with an intact hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, ACTH ApEn is age, gender, and body mass index independent (40).

The clinical consequence of this detailed study is that there is no reason for concern for (subtle) activation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients using pure MR-blocking agents in the eplerenone class for the treatment of hypertension. Moreover, this work highlights the finding that men and women differ in ACTH feedback regulation by a nearly physiological pulsatile cortisol signal, without invoking sex steroid differences per se as the explanation. Finally, the paradigm presented here, albeit complex, offers a potential framework for other precise quantifiable cortisol feedback studies in varies pathophysiological states of interest, such as obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, aging, and chronic stress states among others.

Caveats in the present study include the relatively short duration of the E2 and T clamps, the wider range of ages studied, and the receptor specificities of pharmacological probes of MR and GR.

In summary, pulsatile iv cortisol infusions in physiological amounts in low cortisol-clamped healthy subjects diminish ACTH secretion, quantified by mean levels and pulsatile secretion. Pulsatile cortisol feedback was mediated inferably via GR to a significant degree at the pituitary level, which does not exclude additional actions at the paraventricular nucleus and/or limbic structures. ACTH secretion was greater in men and was associated with increased secretory regularity compared with women. In contrast with studies in experimental animals, under the prevailing experimental conditions, men and women manifested no demonstrable effect of sex steroids on ACTH secretory parameters under both endogenously regulated and exogenously stimulated ACTH secretion.

Supplemental material is available.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Smith for support of the manuscript preparation; the Mayo Immunochemical Laboratory for the assay assistance; and the Mayo research nursing staff for implementing the protocol.

Current address for P.A.: Palm Beach Diabetes and Endocrine Specialists, West Palm Beach, Florida.

The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of any federal institution.

This work was supported in part by Grants R01 DK073148 and P30 DK050456 (Metabolic Studies Core of the Minnesota Obesity Center) from the National Institutes of Health. The project described was supported by Grant UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and Grant 60NANB10D005Z from the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Matlab versions of ApEn and deconvolution methodology are available from veldhuis.johannes@mayo.edu.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ApEn

- approximate entropy

- AVP

- arginine vasopressin

- CRU

- clinical research unit

- E2

- estradiol

- GLM

- generalized linear model

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- KTCZ

- ketoconazole

- MR

- mineralocorticoid receptor.

References

- 1. Keenan DM, Licinio J, Veldhuis JD. A feedback-controlled ensemble model of the stress-responsive hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(7):4028–4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Goeij DC, Kvetnansky R, Whitnall MH, Jezova D, Berkenbosch F, Tilders FJ. Repeated stress-induced activation of corticotropin-releasing factor neurons enhances vasopressin stores and colocalization with corticotropin-releasing factor in the median eminence of rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;53(2):150–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Honkaniemi J, Pelto-Huikko M, Rechardt L, et al. Colocalization of peptide and glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivities in rat central amygdaloid nucleus. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;55(4):451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ono N, Samson WK, McDonald JK, Lumpkin MD, Bedran de Castro JC, McCann SM. Effects of intravenous and intraventricular injection of antisera directed against corticotropin-releasing factor on the secretion of anterior pituitary hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(22):7787–7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G. Physiological regulation of peptide messenger RNA colocalization in rat hypothalamic paraventricular medial parvicellular neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1995;352(4):501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rivier C, Vale W. Interaction of corticotropin-releasing factor and arginine vasopressin on adrenocorticotropin secretion in vivo. Endocrinology. 1983;113(3):939–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dallman MF. Fast glucocorticoid actions on brain: back to the future. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(3–4):103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watts AG. Glucocorticoid regulation of peptide genes in neuroendocrine CRH neurons: a complexity beyond negative feedback. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(3–4):109–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bergendahl M, Vance ML, Iranmanesh A, Thorner MO, Veldhuis JD. Fasting as a metabolic stress paradigm selectively amplifies cortisol secretory burst mass and delays the time of maximal nyctohemeral cortisol concentrations in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(2):692–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Invitti C, De Martin M, Delitala G, Veldhuis JD, Cavagnini F. Altered morning and nighttime pulsatile corticotropin and cortisol release in polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolism. 1998;47(2):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iranmanesh A, Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML, Lizarralde G. Twenty-four hour pulsatile and circadian patterns of cortisol secretion in alcoholic men. J Androl. 1989;10:54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van den Berg G, Veldhuis JD, Frolich M, Roelfsema F. An amplitude-specific divergence in the pulsatile mode of GH secretion underlies the gender difference in mean GH concentrations in men and premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(7):2460–2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roelfsema F, van den Berg G, Frolich M, et al. Sex-dependent alteration in cortisol response to endogenous adrenocorticotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kitay JI. Sex differences in adrenal cortical secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 1961;68:818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergendahl M, Iranmanesh A, Pastor C, Evans WS, Veldhuis JD. Homeostatic joint amplification of pulsatile and 24-hour rhythmic cortisol secretion by fasting stress in midluteal phase women: concurrent disruption of cortisol-growth hormone, cortisol-luteinizing hormone, and cortisol-leptin synchrony. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(11):4028–4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gusenoff JA, Harman SM, Veldhuis JD, et al. Cortisol and GH secretory dynamics, and their interrelationships, in healthy aged women and men. Am J Physiol. 2001;280(4):E616–E625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeBattista C, Belanoff J, Glass S, et al. Mifepristone versus placebo in the treatment of psychosis in patients with psychotic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams GH, Burgess E, Kolloch RE, et al. Efficacy of eplerenone versus enalapril as monotherapy in systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(8):990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veldhuis JD, Iranmanesh A, Lizarralde G, Johnson ML. Amplitude modulation of a burst-like mode of cortisol secretion subserves the circadian glucocorticoid rhythm in man. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:E6–E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson RE, Grebe SK, OKane DJ, Singh RJ. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of estradiol and estrone in human plasma. Clin Chem. 2004;50(2):373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh RJ. Validation of a high throughput method for serum/plasma testosterone using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Steroids. 2008;73(13):1339–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu PY, Keenan DM, Kok P, Padmanabhan V, O'Byrne KT, Veldhuis JD. Sensitivity and specificity of pulse detection using a new deconvolution method. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(2):E538–E544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Veldhuis JD, Pincus SM. Orderliness of hormone release patterns: a complementary measure to conventional pulsatile and circadian analyses. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Veldhuis JD, Keenan DM, Pincus SM. Motivations and methods for analyzing pulsatile hormone secretion. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(7):823–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Brien PC. The appropriateness of analysis of variance and multiple-comparison procedures. Biometrics. 1983;39(3):787–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carey MP, Deterd CH, De Koning J, Helmerhorst F, de Kloet ER. The influence of ovarian steroids on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation in the female rat. J Endocrinol. 1995;144(2):311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burgess LH, Handa RJ. Chronic estrogen-induced alterations in adrenocorticotropin and corticosterone secretion, and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated functions in female rats. Endocrinol. 1992;131(3):1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiser MJ, Handa RJ. Estrogen impairs glucocorticoid dependent negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via estrogen receptor α within the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2009;159(2):883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sharma AN, Aoun P, Wigham JR, Weist SM, Veldhuis JD. Estradiol, but not testosterone, heightens cortisol-mediated negative feedback on pulsatile ACTH secretion and ACTH approximate entropy in unstressed older men and women. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306(9):R627–R635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atkinson HC, Wood SA, Castrique ES, Kershaw YM, Wiles CC, Lightman SL. Corticosteroids mediate fast feedback of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via the mineralocorticoid receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(6):E1011–E1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keller-Wood ME, Yates FE. Corticosteroid inhibition of ACTH secretion. Endocr Rev. 1984;5:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Russell GM, Henley DE, Leendertz J, et al. Rapid glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal ultradian activity in healthy males. J Neurosci. 2010;30(17):6106–6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Russell GM, Kalafatakis K, Lightman SL. The importance of biological oscillators for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity and tissue glucocorticoid response: coordinating stress and neurobehavioural adaptation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2015;27(6):378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamaji M, Tsutamoto T, Kawahara C, et al. Effect of eplerenone versus spironolactone on cortisol and hemoglobin A(1)(c) levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2010;160(5):915–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cornelisse S, Joels M, Smeets T. A randomized trial on mineralocorticoid receptor blockade in men: effects on stress responses, selective attention, and memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(13):2720–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hlavacova N, Bakos J, Jezova D. Eplerenone, a selective mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, exerts anxiolytic effects accompanied by changes in stress hormone release. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(5):779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Struthers A, Krum H, Williams GH. A comparison of the aldosterone-blocking agents eplerenone and spironolactone. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31(4):153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Iranmanesh A, Veldhuis JD. Hypocortisolemic clamp unmasks jointly feedforward- and feedback-dependent control of overnight ACTH secretion. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159(5):561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iranmanesh A, Lawson D, Dunn B, Veldhuis JD. Glucose ingestion selectively amplifies ACTH and cortisol secretory-burst mass and enhances their joint synchrony in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):2882–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Veldhuis JD, Roelfsema F, Iranmanesh A, Carroll BJ, Keenan DM, Pincus SM. Basal, pulsatile, entropic (patterned) and spiky (staccato-like) properties of ACTH secretion: impact of age, gender and body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(10):4045–4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]