Abstract

We and others have reported that the serum procalcitonin (PCT) level has a demonstrative role in predicting the long-term mortality after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) in Chinese population. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms remain ill-defined. In the current study, we further detected a close association of stool microRNA-637 (miR-637) levels with the long-term mortality after AIS in Chinese population. Moreover, the serum PCT and stool miR-637 levels appeared to be inversely correlated. AIS patients with lower levels of stool miR-637 appeared to predict more severe mortality in the long-term. Since PCT has been shown to be mainly produced by the neuroendocrine cells in the intestine, we used an intestine neuroendocrine cell line to study the relationship between miR-637 and PCT. Bioinformatics analyses showed that miR-637 targeted the 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA to inhibit its translation, and thus the levels of PCT protein production and secretion, which was proved by luciferase reporter assay. Together, our data reveal that the molecular mechanisms underlying application of serum PCT and stool miR-637 in prognosis of AIS, in which miR-637 in intestine neuroendocrine cells may be reduced during AIS to allow more PCT to be released into serum to be detected.

Keywords: Procalcitonin (PCT), acute ischemic stroke (AIS), miR-637

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common cause of death and the leading cause of adult disability in China [1]. Early detection and control of risk factors appear to be important for reducing the risk for stroke and providing optimized and effective care [2-6]. In line with these views, the application of appropriate biomarkers to improve the diagnostic accuracy of stroke is extremely critical for improving the outcome of the therapy.

Basic and clinical researches have shown that inflammation plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of stroke. Some Inflammatory markers may predicted the stroke severity and outcome. Among these markers, the high sensitivity C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP) levels and Procalcitonin (PCT) levels have been extensively studied [7-12].

PCT is a protein of 116 amino acids with a molecular weight of 13 kDa, and was discovered as a prohormone of calcitonin produced by C-cells of the thyroid gland and intracellularly cleaved by proteolytic enzymes to form the active hormone. The major site of PCT production during inflammation has been shown to be the neuroendocrine cells in the intestine [13]. Moreover, an early and transient release of PCT into the circulation was observed after severe trauma and the amount of circulating PCT seemed proportional to the severity of tissue injury [14]. Furthermore, the levels of PCT were independently associated with ischemic stroke risk [15-17]. Recently, we reported that serum levels of PCT and high sensitivity C-reactive protein were associated with long-term mortality in AIS [18]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the molecular mechanisms underlying the serum PCT as a predictor of the long-term mortality after AIS are largely unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding small RNAs that regulate of the protein translation through their base-pairing with the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of the target mRNAs [19,20]. It is well-known that miRNAs regulate different biological processes both physiologically and pathologically [21-23]. Among all miRNAs, miR-637 has been rarely studied. First, miR-637 was reported as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma, and appeared to exert its anti-cancer function via disrupting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling [24]. In another study, expression of miR-637 has been associated in ATP6V0A1 polymorphism for development of essential hypertension [25]. However, a role of miR-637 in prediction of outcome of AIS and its relationship with PLT have not been studied before.

In the current study, we addressed these questions. We detected a close association of stool miR-637 levels with the long-term mortality after AIS in Chinese population. Moreover, the serum PCT and stool miR-637 levels appeared to be inversely correlated. AIS patients with lower levels of stool miR-637 appeared to predict more severe mortality in the long-term. Since PCT has been shown to be mainly produced by the neuroendocrine cells in the intestine, we used an intestine neuroendocrine cell line to study the relationship between miR-637 and PCT. Bioinformatics analyses showed that miR-637 targeted the 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA to inhibit its translation, and thus the levels of PCT protein production and secretion, which was proved by luciferase reporter assay.

Materials and methods

Patient tissue specimens

We conducted a prospective cohort study at Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital of Tongji University. From 2010 to 2014, all patients with an AIS event were included in this study. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were admitted to the Emergency Department with a diagnosis of AIS, based on the World Health Organization criteria and with symptom onset within 24 h. We excluded patients with intracranial hemorrhage, a history of recent surgery or trauma during the preceding 2 months, renal insufficiency, malignancy, febrile disorders, acute or chronic inflammatory disease at study enrollment, autoimmune diseases, severe edema or a prior myocardial infarction onset less than 3 months, as well as those with a history of valvular heart disease, or intracardiac thrombus on echocardiograph. In addition, patients with no evidence of infarction on CT or MRI within 24 h after symptom onset were excluded from the study. The control cases (N=200) were of similar age and gender distribution to the AIS patients. They had no known related diseases and were free of medication. The median age of controls included in this study was 69 (IQR, 62-79) years and 45.0% were women. A detailed medical history was taken and clinical and laboratory examinations were performed on all participants in both groups [18]. For the use of these clinical materials or data for research purposes, prior patient’s consents and approval from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital of Tongji University were obtained.

Clinical variables

The clinical variables have been described before [18]. Age, gender, stroke etiology, blood pressure, leukocyte count, and presence of risk factors were examined. Stroke cause was determined according to the criteria of the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification, which distinguishes large-artery arteriosclerosis cardio embolism, small-artery occlusion, other causative factor, and undetermined causative factor. The clinical stroke syndrome was determined by applying the criteria of the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project: total anterior circulation syndrome (TACS); partial anterior circulation syndrome (PACS); lacunar syndrome (LACS); and posterior circulation syndrome (POCS). The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was assessed on admission.

Diagnosis of stroke by neuroimaging

Stroke was diagnosed by neuroradiological examination (brain computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or both) according to the International Classification of Diseases, as has been described before [18].

End points and follow-up

One-year follow-up was selected for the current study. The end point of this study was death from any causes within a one-year follow-up. The death was considered as an outcome variable. One-year mortality was defined as long-term mortality.

Blood collection and PCT quantification

Blood samples of the inpatients were prospectively drawn from the antecubital vein. After centrifugation, serum of the samples were immediately stored at -80°C before assay. PCT was measured in blood samples or cells or conditioned media, using Enzyme-Linked Fluorescent Assay by VIDAS B.R.A.H.M.S. (Biomerieux, Durham, USA). The detection range was 0-200 ng/ml.

Stool cell isolation

The dropped intestine cells were isolated from the stool using published method [26-28]. The miRNAs were then isolated from these cells.

Culture of a human intestine neuroendocrine cell line

A human ileal neuroendocrine tumor cell line CNDT2.5 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) [29], and grown in a humidified 37°C incubator in 5% CO2 and cultured in D-MEM/F12 (Eagle’s minimal essential medium/F12) 1:1 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PEST), 1% 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% vitamins, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% non-essential amino acid (NEAA).

Plasmid transfection

MiR-637-modulating plasmids were prepared from a backbone plasmid containing a GFP reporter under CMV promoter (pcDNA3.1-CMV-GFP, Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The miR-637 mimic, or antisense, or control null was all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and digested with Xhol and BamHI and then subcloned with a 2A into the pcDNA3.1-CMV-GFP plasmid. Sequencing was performed to confirm the correct orientation of the new plasmid. Transfection was done using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. One day after transfection, the transfected cells were purified by flow cytometry based on GFP expression.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from clinical specimens or from cultured cells using a miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was randomly primed from total RNA using the Omniscript reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) were performed in duplicates with QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). All primers were purchased from Qiagen. Data were collected and analyzed using 2-ΔΔCt method for quantification of the relative mRNA expression levels. Values of genes were first normalized against α-tubulin, and then compared to controls.

MicroRNA target prediction and 3’-UTR luciferase-reporter assay

MiRNAs targets were predicted with the algorithms TargetSan (https://www.targetscan.org) [30]. Luciferase-reporters were successfully constructed using molecular cloning technology. The PCT 3’-UTR reporter plasmid (PCT 3’-UTR) and PCT 3’-UTR reporter plasmid with a mutant at the miR-637 binding site (PCT 3’-UTR mut) were purchased from Creative Biogene (Shirley, NY, USA). CNDT2.5 cells were co-transfected with PCT 3’-UTR/PCT 3’-UTR mut and miR-637/as-miR-637/null by Lipofectamine 2000 (5×104 cells per well). Cells were collected 24 hours after transfection for assay using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system gene assay kit (Promega, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The normalized control was null-transfected CNDT2.5 cells with 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA (wild type).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 17.0 statistical software package. Bivariate correlations were calculated by Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficients. Kaplan-Meier curves were sued to analyze the patient survival by miR-637 levels. All values are depicted as mean ± SD and are considered significant if p < 0.05. All data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction, followed by Fisher’s Exact Test for comparison of two groups.

Results

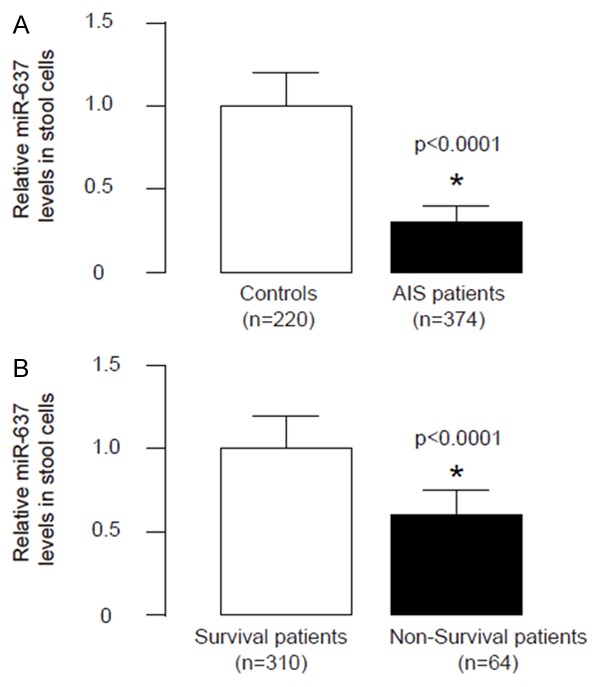

Stool cell miR-637 is low in AIS patients, and even lower in AIS with long term mortality

We have previously shown that the serum PCT levels appear to be significantly higher in stroke patients as compared to normal controls, and are even higher in those with long term mortality. In order to understand the underlying mechanisms, we isolated stool cells from the patients and analyzed PCT-targeting miRNAs levels, since PCT has been shown mainly produced by intestine neuroendocrine cells that could be detected in the stool. Specifically, we found that the levels of miR-637 were significantly lower in the stool from the AIS patients (Figure 1A), and were even lower in AIS patients with long term mortality (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Stool cell miR-637 is low in AIS patients, and even lower in AIS with long term mortality. (A, B) The levels of miR-637 were significantly lower in the stool from the AIS patients (A) compared with control cases, and were even lower in AIS patients with long term mortality (B) than those not. *p < 0.0001.

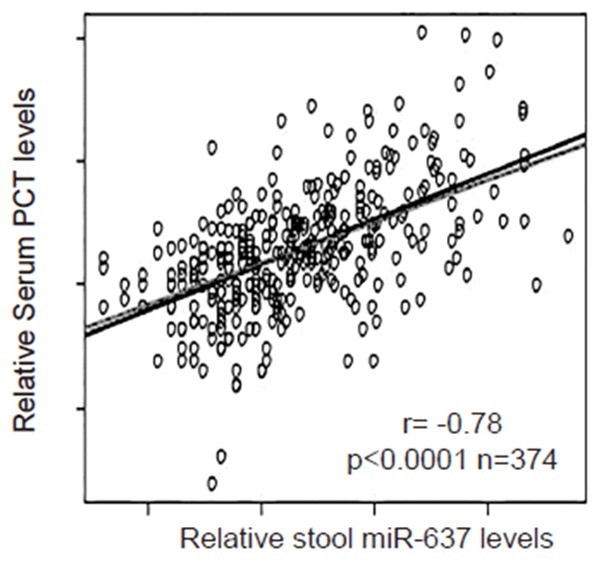

Stool miR-367 inversely correlates with serum PCT

Then we examined the relationship between stool miR-637 and serum PCT in AIS patients. Thus, we performed a correlation test using the 374 cases. A strong inverse correlation was detected between stool miR-637 and serum PCT (Figure 2, ɤ=-0.78, p < 0.0001, n=374), suggesting that a regulatory relationship between stool miR-637 and serum PCT may be present in AIS patients.

Figure 2.

Stool miR-367 inversely correlates with serum PCT. We examined the relationship between stool miR-637 and serum PCT in AIS patients using a correlation test. A strong inverse correlation was detected between stool miR-637 and serum PCT (ɤ= -0.78, p < 0.0001, n=374).

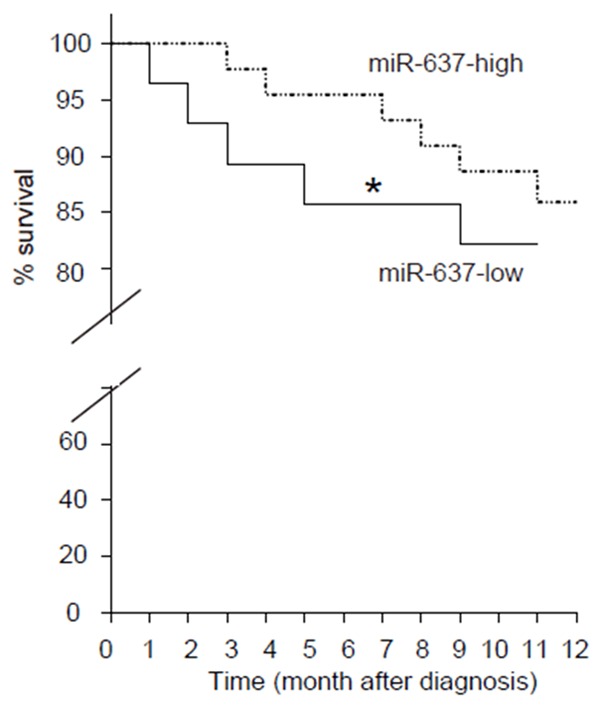

Low stool miR-367 predicts long term mortality of AIS patients

Next, we investigated whether the levels of stool miR-637 may correlate with long term mortality of the patients. The median value for miR-637 in all 374 cases was chosen as the cutoff point for separating miR-637-high cases (n=187) from miR-637-low cases (n=187). Kaplan-Meier curves were performed, showing that miR-637-low patients had a significantly poorer survival, compared to miR-637-high patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Low stool miR-367 predicts long term mortality of AIS patients. We investigated whether the levels of stool miR-637 may correlate with long term mortality of the patients. The median value for miR-637 in all 374 cases was chosen as the cutoff point for separating miR-637-high cases (n=187) from miR-637-low cases (n=187). Kaplan-Meier curves were performed, showing that miR-637-low patients had a significantly poorer survival, compared to miR-637-high patients. *p < 0.01.

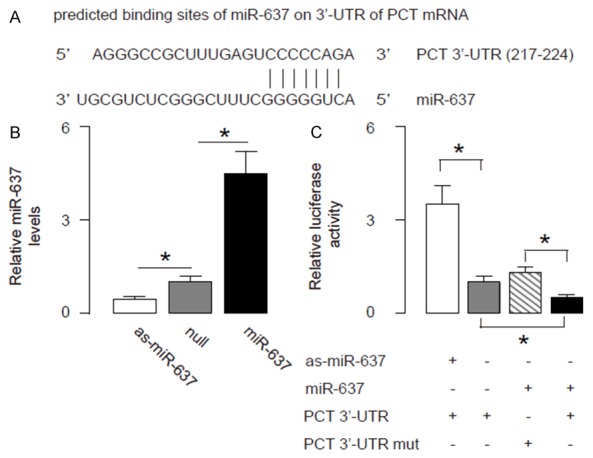

MiR-637 targets 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA to inhibit its protein translation

In order to prove presence of a regulatory relationship between stool miR-637 and serum PCT, we used bioinformatics analyses to predict binding of miR-637 on PCT mRNA. We detected a specific miR-637 binding site on the 3’-UTR (from 217th to 224th base site) of the PCT mRNA (Figure 4A). Next, we analyzed whether this binding of miR-637 to PCT mRNA may alter the PCT levels. Thus, we either overexpressed miR-637, or inhibited miR-637 in a human ileal neuroendocrine tumor cell line CNDT2.5, by a miR-637-expressing plasmid, or a plasmid carrying miR-637 antisense (as-miR-637), respectively. The CNDT2.5 cells were also transfected with a null plasmid, to be used as a control for miR-637 modification (Nul). First of all, the alteration of miR-637 levels in CNDT2.5 cells was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure 4B). CNDT2.5 cells were then transfected with 1 μg plasmids of miR-637-modification plasmids, with plasmids carrying a luciferase reporter for 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA or a luciferase reporter for 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA with mutate at the miR-637 binding site (mut). The luciferase activities were determined in these cells, and our data showed that PCT 3’-UTR plus miR-637 had the most repression for PCT, and the 3’-UTR PCT mutant plus miR-637 had much lower repression. Moreover, the 3’-UTR in the presence of as-miR-454 restored expression of PCT (Figure 4C). These data demonstrate that miR-637 may target 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA to inhibit its translation.

Figure 4.

MiR-637 targets 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA to inhibit its protein translation. A. Bioinformatics analyses of binding of miR-637 to the 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA. B, C. We either overexpressed miR-637, or inhibited miR-637 in a human ileal neuroendocrine tumor cell line CNDT2.5, by a miR-637-expressing plasmid, or a plasmid carrying miR-637 antisense (as-miR-637), respectively. The CNDT2.5 cells were also transfected with a null plasmid, to be used as a control for miR-637 modification (Nul). B. First of all, the alteration of miR-637 levels in CNDT2.5 cells was confirmed by RT-qPCR. C. CNDT2.5 cells were then transfected with 1 μg plasmids of miR-637-modification plasmids, with plasmids carrying a luciferase reporter for 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA or a luciferase reporter for 3’-UTR of PCT mRNA with mutate at the miR-637 binding site (mut). The luciferase activities were quantified. *p < 0.05. N=5.

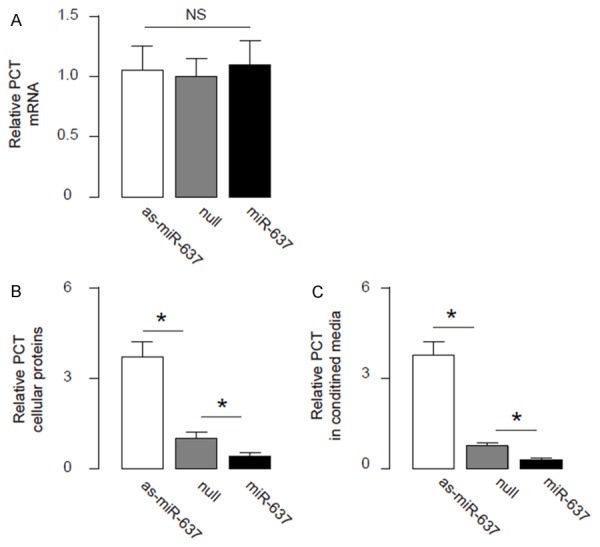

MiR-637 reduces production and secretion of PCT protein in intestine neuroendocrine cells

Next, we analyzed the effects of modification of miR-637 levels on PCT in CNDT2.5 cells. We found that alteration of miR-637 in CNDT2.5 cells did not change PCT mRNA (Figure 5A). However, overexpression of miR-637 significantly decreased PCT cellular protein (Figure 5B) and secreted protein (Figure 5C). On the other hand, inhibition of miR-637 significantly increased PCT cellular protein (Figure 5B) and secreted protein (Figure 5C). These data suggest that miR-637 inhibits PCT protein translation in intestine neuroendocrine cells. Together, our data suggest that AIS-induced inflammation may suppress miR-637 to allow PCT production and secretion in intestine neuroendocrine cells to be detected in the serum (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

MiR-637 reduces PCT protein in OSCC cells. (A-C) RT-qPCR (A), cellular protein ELISA (B) and secreted protein ELISA (C) for PCT in miR-637-modified cells. *p < 0.05. NS: non-significant. N=5.

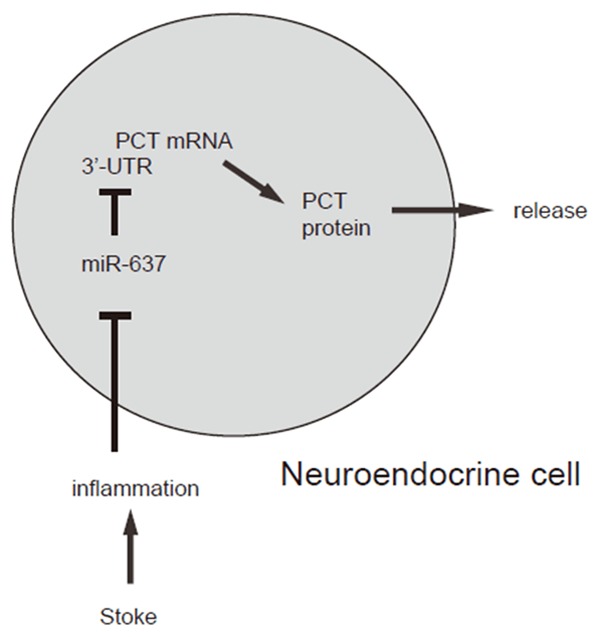

Figure 6.

Schematic of the model. AIS-induced inflammation may suppress miR-637 to allow PCT production and secretion in intestine neuroendocrine cells to be detected in the serum.

Discussion

Our previous study has shown that serum PCT levels were significantly elevated in AIS cases than controls, and in cases of AIS with long term mortality than those not [18]. Together with studies from other groups [15-17], we have demonstrated that an elevated PCT level might be an independent risk factor and prognosis marker for AIS. Moreover, we have shown described that the elevated serum PCT levels with increasing severity of stroke, as defined by the NIHSS score [18]. However, none of the previous studies have shown the molecular basis that could explain the elevated PCT levels with the onset of AIS.

Indeed, previous researches have shown that the major site of PCT production during inflammation has been shown to be the neuroendocrine cells in the intestine [13]. Moreover, an early and transient release of PCT into the circulation was observed after severe trauma and the amount of circulating PCT seemed proportional to the severity of tissue injury [14]. Thus, we hypothesized that the AIS-associated inflammation may change the expression of PCT in neuroendocrine cells in the intestine. In order to text this hypothesis, we performed an examination of the PCT levels in the isolated cells from the stool, since examination of these cells in the stool is clinically possible and the assay could be translatable. To our surprise, we detected changes in PCT protein but not mRNA in the stool cells (data not shown) after AIS. Hence, we think that the post-transcriptional control of PCT may occur in these patients. Since miRNAs are major factors that regulate PCT protein translation, we approached to screen PCT-targeting miRNAs and found that the levels of miR-637 were significantly lower in the stool from the AIS patients, and were even lower in AIS patients with long term mortality. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report miR-637 as a suppressor of PCT in neuroendocrine cells in AIS.

Moreover, the levels of stool miR-637 and serum PCT inversely correlated and stool miR-637 appeared to be as sensitive marker as serum PCT for AIS diagnosis and prediction for long term mortality. These findings were further confirmed by in vitro tests of the relationship between miR-637 and PCT using a neuroendocrine cell line.

To summarize, here we propose a model that AIS-induced inflammation may suppress miR-637 to allow PCT production and secretion in intestine neuroendocrine cells to be detected in the serum.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Campos F, Sobrino T, Ramos-Cabrer P, Castillo J. Oxaloacetate: a novel neuroprotective for acute ischemic stroke. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qi J, Liu Y, Yang P, Chen T, Liu XZ, Yin Y, Zhang J, Wang F. Heat shock protein 90 inhibition by 17-Dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin protects blood-brain barrier integrity in cerebral ischemic stroke. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:1826–1837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuen CM, Chung SY, Tsai TH, Sung PH, Huang TH, Chen YL, Chen YL, Chai HT, Zhen YY, Chang MW, Wang CJ, Chang HW, Sun CK, Yip HK. Extracorporeal shock wave effectively attenuates brain infarct volume and improves neurological function in rat after acute ischemic stroke. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:976–994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng F, Lu XC, Hao HY, Dai XL, Qian TD, Huang BS, Tang LJ, Yu W, Li LX. Neurogenin 2 converts mesenchymal stem cells into a neural precursor fate and improves functional recovery after experimental stroke. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:847–858. doi: 10.1159/000358657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Uriz AM, Goyenechea E, Campion J, de Arce A, Martinez MT, Puchau B, Milagro FI, Abete I, Martinez JA, Lopez de Munain A. Epigenetic patterns of two gene promoters (TNF-alpha and PON) in stroke considering obesity condition and dietary intake. J Physiol Biochem. 2014;70:603–614. doi: 10.1007/s13105-014-0316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murad LB, Guimaraes MR, Paganelli A, de Oliveira CA, Vianna LM. Alpha-tocopherol in the brain tissue preservation of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol Biochem. 2014;70:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s13105-013-0279-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, Coresh J, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Myerson M, Wu KK, Sharrett AR, Boerwinkle E. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident ischemic stroke in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2479–2484. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elkind MS, Tai W, Coates K, Paik MC, Sacco RL. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, and outcome after ischemic stroke. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2073–2080. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lip GY, Patel JV, Hughes E, Hart RG. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and soluble CD40 ligand as indices of inflammation and platelet activation in 880 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: relationship to stroke risk factors, stroke risk stratification schema, and prognosis. Stroke. 2007;38:1229–1237. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260090.90508.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elkind MS, Leon V, Moon YP, Paik MC, Sacco RL. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 stability before and after stroke and myocardial infarction. Stroke. 2009;40:3233–3237. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkind MS, Luna JM, Moon YP, Liu KM, Spitalnik SL, Paik MC, Sacco RL. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein predicts mortality but not stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology. 2009;73:1300–1307. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd10bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nambi V, Hoogeveen RC, Chambless L, Hu Y, Bang H, Coresh J, Ni H, Boerwinkle E, Mosley T, Sharrett R, Folsom AR, Ballantyne CM. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein improve the stratification of ischemic stroke risk in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2009;40:376–381. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruna P, Nedelnikova K, Gurlich R. Physiology and genetics of procalcitonin. Physiol Res. 2000;49(Suppl 1):S57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mimoz O, Benoist JF, Edouard AR, Assicot M, Bohuon C, Samii K. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein during the early posttraumatic systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:185–188. doi: 10.1007/s001340050543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fluri F, Morgenthaler NG, Mueller B, Christ-Crain M, Katan M. Copeptin, procalcitonin and routine inflammatory markers-predictors of infection after stroke. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hug A, Murle B, Dalpke A, Zorn M, Liesz A, Veltkamp R. Usefulness of serum procalcitonin levels for the early diagnosis of stroke-associated respiratory tract infections. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14:416–422. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyakis S, Georgakopoulos P, Kiagia M, Papadopoulou O, Pefanis A, Gonis A, Mountokalakis TD. Serial serum procalcitonin changes in the prognosis of acute stroke. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;350:237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li YM, Liu XY. Serum levels of procalcitonin and high sensitivity C-reactive protein are associated with long-term mortality in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2015;352:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Leva G, Croce CM. miRNA profiling of cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira DM, Rodrigues PM, Borralho PM, Rodrigues CM. Delivering the promise of miRNA cancer therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mei Q, Li F, Quan H, Liu Y, Xu H. Busulfan inhibits growth of human osteosarcoma through miR-200 family microRNAs in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:755–762. doi: 10.1111/cas.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Xiao W, Sun J, Han D, Zhu Y. MiRNA-181c inhibits EGFR-signaling-dependent MMP9 activation via suppressing Akt phosphorylation in glioblastoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8653–8658. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu G, Jiang C, Li D, Wang R, Wang W. MiRNA-34a inhibits EGFR-signaling-dependent MMP7 activation in gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:9801–9806. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang JF, He ML, Fu WM, Wang H, Chen LZ, Zhu X, Chen Y, Xie D, Lai P, Chen G, Lu G, Lin MC, Kung HF. Primate-specific microRNA-637 inhibits tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by disrupting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling. Hepatology. 2011;54:2137–2148. doi: 10.1002/hep.24595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Contu R, Condorelli G. ATP6V0A1 polymorphism and microRNA-637: A pathogenetic role for microRNAs in essential hypertension at last? Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:337–338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanaoka S, Yoshida K, Miura N, Sugimura H, Kajimura M. Potential usefulness of detecting cyclooxygenase 2 messenger RNA in feces for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:422–427. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slaby O, Svoboda M, Michalek J, Vyzula R. MicroRNAs in colorectal cancer: translation of molecular biology into clinical application. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:102. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:581–585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Buren G 2nd, Rashid A, Yang AD, Abdalla EK, Gray MJ, Liu W, Somcio R, Fan F, Camp ER, Yao JC, Ellis LM. The development and characterization of a human midgut carcinoid cell line. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4704–4712. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coronnello C, Benos PV. ComiR: Combinatorial microRNA target prediction tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W159–164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]