Abstract

CD4+ T helper 9 (Th9) cells are a newly discovered Th cell subset that produce the pleiotropic cytokine IL-9. Th9 cells can protect against tumors and provide resistance against helminth infections. Given their pivotal role in the adaptive immune system, understanding Th9 cell development and the regulation of IL-9 production could open novel immunotherapeutic opportunities. The Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1; gene name Slc9α1)) is critically important for regulating intracellular pH (pHi), cell volume, migration, and cell survival. The pHi influences cytokine secretion, activities of membrane-associated enzymes, ion transport, and other effector signaling molecules such as ATP and Ca2+ levels. However, whether NHE1 regulates Th9 cell development or IL-9 secretion has not yet been defined. The present study explored the role of NHE1 in Th9 cell development and function. Th cell subsets were characterized by flow cytometry and pHi was measured using 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein-acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) dye. NHE1 functional activity was estimated from the rate of realkalinization following an ammonium pulse. Surprisingly, in Th9 cells pHi and NHE1 activity were significantly higher than in all other Th cell subsets (Th1/Th2/Th17 and induced regulatory T cells (iTregs)). NHE1 transcript levels and protein abundance were significantly higher in Th9 cells than in other Th cell subsets. Inhibition of NHE1 by siRNA-NHE1 or with cariporide in Th9 cells down-regulated IL-9 and ATP production. NHE1 activity, Th9 cell development, and IL-9 production were further blunted by pharmacological inhibition of protein kinase Akt1/Akt2. Our findings reveal that Akt1/Akt2 control of NHE1 could be an important physiological regulator of Th9 cell differentiation, IL-9 secretion, and ATP production.

Keywords: cancer, cellular regulation, interleukin, pH regulation, T helper cells, NHE1, Th9 cells, iTregs

Introduction

CD4+ T cells participate in the regulation of the immune response during infections, autoimmunity, and cancer. CD4+ T cells are an important and essential arm of the adaptive immune system (1). CD4+ T cells can be divided into various subtypes based upon their cytokine secretion: T helper 1 (Th1)4 cells produce IFN-γ (1, 2), Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (3), Th17 cells produce IL-17 (4–6), Th9 cells produce IL-9 (7–9), and suppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) produce TGF-β and IL-10 (10). A great deal of experimental effort has been dedicated to decipher the development and function of various Th cell subsets. However, Th9 cell development and function remain incompletely understood.

Th9 cells are a recently characterized Th cell subset recognized by their potent production of IL-9. Th9 cells play a pivotal role in health and disease. Th9 cells have been shown to exacerbate the airway allergic immune response by recruiting eosinophils and mast cells to the lungs, increasing mucus production, and production of serum IgE (11, 12). Th9 cells further contribute to the host-immune reaction against helminth infections and tumors (7, 13–23). The development and function of Th9 cells are regulated by a constellation of key transcription factors that include Gata3 (7), Pu.1 (13), Stat6 (24), Irf-4 (25), Irf-1 (26), Bcl6 (27), and Batf (28). However, a single faithful transcription factor for Th9 cell development has not yet been described. Recent studies have also implicated glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related gene (GITR; gene name Tnfrsf18) signaling in Th9 cell development (29, 30). Xiao et al. (29) found that GITR signaling controlled chromatin remodeling at the Foxp3 and Il9 loci, and consequently was able to convert induced Tregs (iTregs) into Th9 cells. Furthermore, microRNA-15b/16 (miR-15b/16) is involved in fine tuning of iTregs/Th9 cell development thus contributing to the autoinflammation in colitis (31).

Th cells (Th1, Th2, Th17, and iTregs) are different in their energy production and metabolism (32–34). Th cells normally use the aerobic glycolytic pathway to meet their energy demand for cell proliferation and development, with the exception of iTregs, which uses oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (32–35). All major intracellular processes such as glycolysis-dependent ATP production or protein synthesis require tight regulation of intracellular pH (pHi) (36). Maintenance of glycolysis and OXPHOS processing enzymes are highly dependent on pHi. Accordingly, pHi could modify cellular metabolism (37). Understanding regulation of pHi and Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) activity could thus open up new avenues to treat autoimmune disorders, allergic inflammation, or cancer by immunotherapeutic manipulation of Th9 cells.

Tight regulation of pHi by NHE proteins (NHE1, -2, and -3) is vital for survival and function of CD4+ T cells (38–44). The pHi and NHE activity are instrumental for preserving cell viability, cell proliferation, and migration (40, 41, 45, 46). pHi is in part affected by modulating signal transduction (40, 41, 45, 47). NHE1 activity is in turn regulated by the protein kinase B (Akt) (48–50). Previous studies in human T cells have suggested that addition of IL-2 to cultured cells could enhance pHi and NHE1 protein abundance, thus affecting cell proliferation, cytokine production, and apoptosis (51). It has been further proposed that pHi and NHE1 activity are modulated by glucocorticoids in a non-genomic fashion (49, 52–56). However, to which extent pHi and NHE activity govern Th9 cell development and function is incompletely understood.

In this study, we explored pHi and NHE1 activity in various Th cell subsets. We found that Th9 cells potently up-regulate pHi and NHE1 activity compared with other Th cell subsets. Furthermore, we show that regulation of NHE1 activity is dependent on Akt. Finally we reveal that, NHE1 controls the development and function of Th9 cells. In summary our data describe a novel role of NHE1 in the development and IL-9 production of Th9 cells.

Results

Characterization of Th Cell Subsets at mRNA and Protein Levels and NHE1 Expression in Th Cell Subsets

To characterize different Th cell subsets, naive CD4+ T cells were differentiated into Th1, Th2, Th9, Th17, and iTregs in the presence of defined recombinant cytokine proteins and antibodies as described under “Experimental Procedures.” To confirm differentiation, the respective cytokines and transcription factors of particular Th cell subsets and iTregs, were measured by flow cytometry (data not shown). The results were further supported by q-RT-PCR. Th1 cells produce IFN-γ transcripts and Th2 cells produce IL-4 transcripts (data not shown). Th9 cells are the major producer of IL-9 transcripts. IL-9 transcripts were also produced, albeit to a lower extent, by Th2 and iTregs. Th17 cells mainly produced IL-17 transcripts. Induction of Foxp3 transcripts were only associated with iTregs. These results confirmed that our naive T cells were correctly differentiated into various Th cell subsets and iTregs.

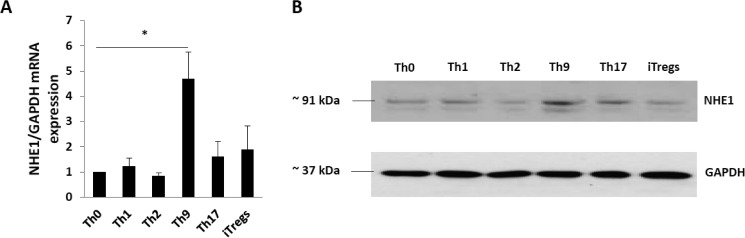

Transcript levels of NHE1 were quantified in Th cell subsets and iTregs by q-RT-PCR. NHE1 mRNA transcript levels were significantly higher in Th9 cells than in Th0, other Th cell subsets (Th1, Th2, and Th17), and iTregs (Fig. 1A). Immunoblotting revealed that the differences in NHE1 transcript levels were paralleled by differences in NHE1 protein abundance (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Again, Th9 cells expressed the highest amount NHE1 protein.

FIGURE 1.

NHE1 expression in Th cell subsets and iTregs at mRNA and protein levels. A, naive T cells were differentiated in Th cell subsets and iTregs as described under ”Experimental Procedures“ and RNA was isolated for q-RT-PCR to quantify NHE1 transcript levels. Arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 5 independent experiments) of the mRNA levels in Th cell subsets is shown. Th9 cells have significantly higher NHE1 RNA expression than all other Th cell subsets and iTregs. Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05). B, NHE1 protein expression in Th cell subsets and iTregs. Gapdh was used as a loading control.

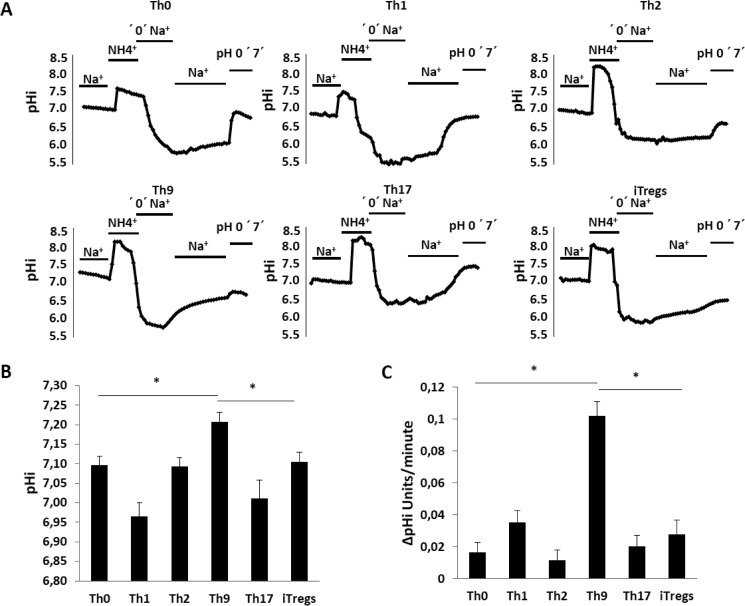

pHi and Na+/H+ Exchanger Activity in Th Cell Subsets and iTregs

To test whether enhanced NHE1 expression in Th9 cells resulted in enhanced Na+/H+ exchanger activity and pHi, cytosolic pHi was estimated from (2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) fluorescence using fluorescence optics. We found that Th0, Th2, and iTregs had similar pHi values (Fig. 2, A and B). To our surprise, Th1 cells had the lowest pHi when compared with all other Th cell subsets including iTregs (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, Th9 had significantly higher pHi than all other Th cell subsets (Fig. 2, A and B). Na+/H+ exchanger activity was measured utilizing the ammonium pulse technique. In this method, addition of 20 mm NH4Cl (replacing NaCl in the superfusate) was followed by NH3 entry into the cells with subsequent transient cytosolic alkalinization due to binding of H+ to NH3 thus forming NH4+. Subsequent removal of NH4Cl was followed by cytosolic acidification due to NH3 exit with cytosolic dissociation of NH4+ and retention of H+. In the absence of Na+, realkalinization was negligible in all Th cell subsets. Thus, none of the Th cell subsets expressed an appreciable Na+-independent H+ extruding transport system. However, the subsequent addition of Na+ was followed by rapid cytosolic realkalinization, an observation pointing to Na+/H+ exchanger activity (Fig. 2, A and C). Na+/H+ exchanger activity was significantly higher in Th9 cells than in any other Th cell subsets (Fig. 2, A and C). Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th9 cells was abrogated in the presence of the NHE1 inhibitor cariporide (data not shown). Thus, these data strongly suggested NHE1 could be involved in development or function of Th9 cells.

FIGURE 2.

pHi and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th cell subsets and iTregs. A, alterations of cytosolic pH (pHi) following an ammonium pulse in Th cell subsets and iTregs. Cells were loaded with H+ by treating with 20 mm NH4Cl. Na+ was then removed by replacement with NMDG. NH4Cl was then removed in a second step and Na+ was added with nigericin (pHo 7.0) to calibrate each individual experiment. Original tracings of typical experiments are shown for pHi measurement and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th cell subsets. B, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 3–5 independent experiments) of cytosolic pH prior to the ammonium pulse (pHi) in Th cell subsets and iTregs. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05). C, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 3–5 independent experiments) of Na+-dependent recovery of cytosolic pH (ΔpH/min) in Th cell subsets. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05).

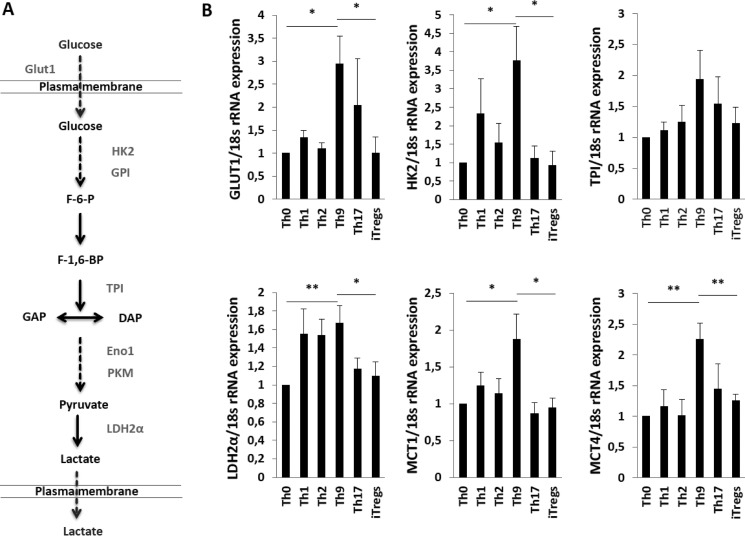

Glycolytic Rate Is Higher in Th9 Cells Than Other Th Cell Subsets and iTregs

Elevated pHi is implicated in neoplastic transformation in response to overexpression of proton transporters and different oncogenes. Oncogenes take advantage of NHE-1-induced cellular alkalinization to produce a unique cancer-specific regulation (36). High pHi leads to increased glycolytic flux in cancer cells reducing the requirement of oxidative phosphorylation (36). Previous studies also suggested that Th cell subsets have different energy requirements (32–35). Th cells primarily use aerobic glycolytic pathways to meet their energy demand, whereas Tregs use OXPHOS for their energy supply (32–35). NHE1 activation can lead to enhanced glycolysis. Glucose consumption is dependent on a series of reactions catalyzed by a chain of multiple enzymes. Catalysis of one molecule of glucose yields two molecules of ATP and lactic acid (a by-product of this process). We postulated that NHE1 activity would therefore affect glycolysis in Th9 cells. We thus performed q-RT-PCR on key regulatory genes in the glycolytic pathway. We found that Th9 cells have the higher expression of glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), hexokinase 2 (Hk2), triose-phosphate isomerase (Tpi), lactate dehydrogenase 2α (Ldh2α), and monocarboxylic acid transporter members 1 and 4 (Mct1 and Mct4) transcript levels than Th0 cells or iTregs (Fig. 3, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

Th9 cells augmented the glycolysis compared with Th cell subsets and iTregs. A, a diagram is shown displaying the enzymes involved in the glycolysis pathway. B, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 5–6 independent experiments) of mRNA transcripts for glycolytic pathways enzymes genes (Glut1, Hk2, Tpi, Ldh2α, Mct1, and Mct4) from Th cell subsets and iTregs. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (**, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

NHE1 Impacts on Regulation of Cell Metabolism, IL-9, and ATP Production

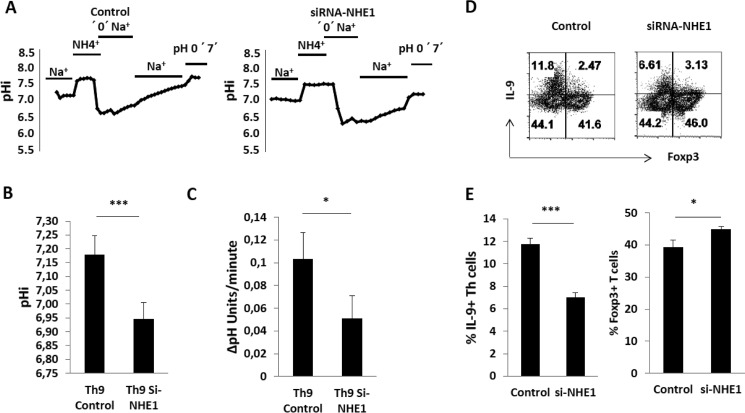

To uncover the functional importance of NHE1 in Th9 cells, we knocked down NHE1 expression in Th9 cells using siRNA. The transfection efficiency of siRNAs was tested using control siRNA, which was labeled with FAM dye. FAM fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry and more than 90% of CD4+ T cells were positive for the FAM dye (data not shown). After NHE1 knockdown, pHi and NHE1 activity were measured using BCECF, which demonstrated a drastically reduced activity of the Na+/H+ exchanger (Fig. 4, A and C) and a decreased pHi (Fig. 4, A and B). NHE1 knockdown further reduced intracellular IL-9 cytokine expression (Fig. 4D) and importantly, the ability of Th9 cells to convert into iTregs (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Regulation of Th9 cells and iTregs development by NHE1. A, alterations of cytosolic pH (pHi) following an ammonium pulse in transfected Th9 cells with control and NHE1 siRNAs. Cells were loaded with H+ as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. Original tracings of typical experiments are shown for pHi measurement and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th cell subsets. B, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 3–5 independent experiments) of cytosolic pH prior to the ammonium pulse (pHi) in siRNA control and siRNA NHE1 Th9 cells. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05). C, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 3–5 independent experiments) of Na+-dependent recovery of cytosolic pH (ΔpH/min) in siRNA control and siRNA NHE1 Th9 cells. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05). D, differentiation of Th9 cells transfected with control and NHE1 siRNAs. At day 4, Th9 cells were activated with PMA, ionomycin, and brefeldin A for 4 h and stained for IL-9 and Foxp3. Representative FACS plots show the Th9 differentiation after knock-down of NHE1. E, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 3–5 independent experiments) of IL-9 and Foxp3 expression in siRNA control and siRNA NHE1 Th9 cells. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05).

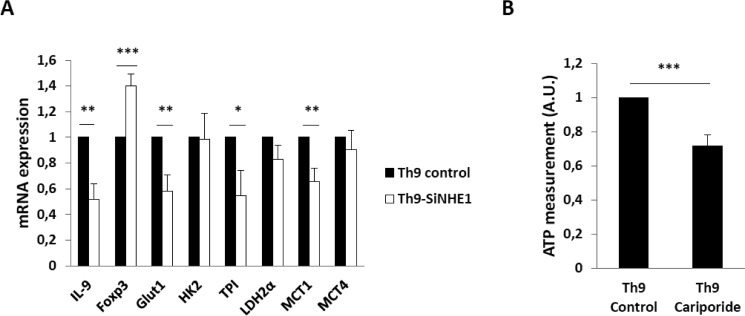

We next explored whether genes in the glycolytic pathway decreased due to the knockdown of NHE1 in Th9 cells. Several genes related to glycolysis such as Glut1, Tpi, and Mct1 were significantly down-regulated (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, siRNA knockdown of NHE1 expression affected Foxp3 mRNA and reduced IL-9 transcript levels. To explore the impact of NHE1 activity on the intracellular energy status of Th9 cells, we measured ATP production in Th9 cells in the presence and absence of the NHE1 inhibitor cariporide. In keeping with the q-RT-PCR data, treatment with cariporide significantly decreased ATP levels in Th9 cells (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

NHE1 inhibition leads to decreased glycolysis and ATP production. A, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 5–6 independent experiments) of mRNA transcripts for glycolytic pathway enzymes genes (Glut1, Hk2, Tpi, Ldh2α, Mct1, and Mct4) from Th9 cells with and without inhibition of NHE1 by siRNAs. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05). B, arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate) of intracellular ATP levels. Naive T cells were differentiated into Th9 cells with or without NHE1 inhibitor cariporide (10 μm) and intracellular ATP was measured using luciferase assay kit. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (***, p < 0.001).

Na+/H+ Exchanger Activity Is Dependent on Akt Signaling in Th9 Cells

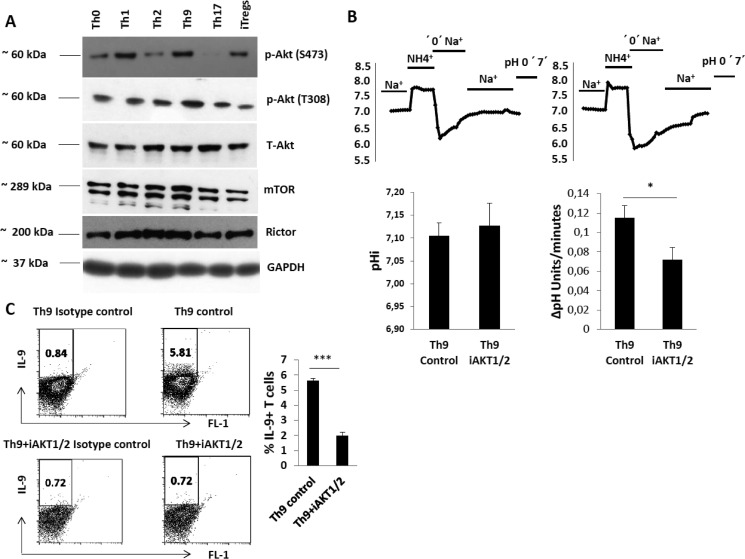

Akt signaling is critically involved in NHE1 regulation (48, 49, 57). Akt/Rictor/mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) signaling is also involved in the development of Th cell subsets (58–61). However, the role of Akt/Rictor/mTOR signaling has not been defined in Th9 cell development. To identify the possible role of Akt and NHE1 in Th9 cell development, we examined Akt/mTOR proteins and their enzymatic activity. We found that the level of Akt phosphorylation at serine 473 (Ser-473) is highest in Th9 and Th1 cells (Fig. 6A and data not shown). In contrast, Akt phosphorylation at threonine 308 (Thr-308) was higher in Th9 than in any other Th cell subsets (Fig. 6A). As Akt Ser-473 is phosphorylated by Rictor, we also measured Rictor expression and found that Th1, Th2, and Th9 cells have higher amounts of Rictor than Th0 and Th17 cells, or iTregs (Fig. 6). However, mTOR expression was higher in Th9 cells than in any other Th cell subsets (Fig. 6A). Therefore, we reasoned that the increased phosphorylation level of Akt at Ser-473/Thr-308 could lead to enhanced expression of NHE1 in Th9 cells. To explore whether Akt influences NHE1 expression, we differentiated naive T cells into Th9 cells in the presence and absence of Akt1/2 inhibitor and measured Na+/H+ exchanger activity. As shown in Fig. 6B, Akt inhibition significantly decreased Na+/H+ exchanger activity. Moreover, inhibition of Akt reduced the expression of IL-9 (Fig. 6C). These data reveal that Akt is crucial for the up-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger activity and IL-9 production in Th9 cells.

FIGURE 6.

Regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger activity and IL-9 production by Akt in Th9 cells. A, levels of total and phosphorylated Akt at Ser-473 and Thr-308 plus levels of Rictor and mTOR in Th cell subsets. Data are representative of Western blot analysis of 4 independent experiments. B, NHE1 activity and pHi of Th9 cells with or without the Akt1/2 inhibitor (0.3 μm). Original tracings of typical experiments for pHi measurement and Na+/H+ exchanger activity are shown. Arithmetic means ± S.E. (n = 3–4 independent experiments) of cytosolic pH prior to the ammonium pulse (pHi) and Na+-dependent recovery of cytosolic pH (ΔpH/min) in Th9 cells with and without Akt1/2 inhibitor are shown. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05). C, a representative FACS plot showing differentiated Th9 cells with and without Akt1/2 inhibitor (0.3 μm). Data are representative of n = 3 experiments. Asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (***, p < 0.0005).

Discussion

The present study uncovered a novel role of cytosolic pH regulation and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in development and function of Th cell subsets, in particular Th9 and iTregs.

Previously, it was suggested that IL-2 signaling could induce NHE1 activity in human T cells (51) as well as in murine T cells (52, 53). In extension to these previous findings, our study revealed that each Th cell subset differs in pHi, which is governed by Na+/H+ exchanger activity. Na+/H+ exchanger activity is highly sensitive to cytosolic pHi and is switched off upon cytosolic alkalinization (62). NHE1 mRNA and protein levels were highest in Th9 cells than in any other Th cell subsets or iTregs. Moreover, Th9 cells had the highest and Th2 cells had the lowest Na+/H+ exchanger activity when compared with all other Th cell subsets (Th0, Th1, and Th17, or iTregs). Up-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th9 cells enhances the extrusion of H+ thus contributing to the maintenance of alkaline pHi.

We further revealed the critical influence of Akt on Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th9 cells. Akt is known to govern the signaling for other Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell subsets and iTregs. However, the role of Akt has not been defined in Th9 cells. We found that Th9 cells had the highest level of Akt phosphorylation. This could be due to high mTOR/Rictor activity in Th9 cells compared with iTregs. This higher activity of Akt could affect the Na+/H+ exchanger activity in Th9 cells as previous studies have suggested a role of Akt in governing the Na+/H+ exchanger activity (48–50). Furthermore, Akt could also be required for up-regulation of IL-9 cytokine expression, as Akt inhibition decreased the expression of IL-9 in Th9 cells. It appears that Akt is vitally important for regulating development and function of Th9 cells. Phosphorylation of Akt is also up-regulated in Th1 cells; however, they do not have an appreciable Na+/H+ exchanger activity.

A recent study also suggested that Th9 cells have increased expression of Hif-2α (31). Hif-2α is upstream of Rictor and it is also up-regulated in Th9 cells. Thus it could contribute to or even account for the enhanced glycolysis. Previous studies have revealed that mTOR is a metabolic sensor in various immune T cells (32, 34). Theoretically, mTOR could regulate glycolysis within Th9 cells. In keeping with a recently published finding (63), the glycolytic rate is higher in Th9 cells than in any other Th cell subsets and iTregs. In contrast to Th9 cells, iTregs depend on OXPHOS for their metabolic energy production. Following NHE1 inhibition, Th9 cells loose glycolytic potential and convert into iTregs. Our data thus confirm that NHE1 is a controller of glycolytic flux in Th9 cells. However, other pathways cannot be ruled out.

The Th9/iTregs axis in cancer is further affected by GITR signaling (29, 30). Our studies suggest that NHE1 could also be instrumental for the Th9/iTregs balance. In view of our siRNA knock-down data, it is tempting to speculate that NHE1 is essential for the Th9/iTregs axis in cancer patients. Tumor cells generate lactate thus leading to a highly acidic environment (64). An adequate immune response against tumor cells requires survival of the respective immune cells in the acidic environment. Augmented Na+/H+ exchanger activity may indeed confer some protection against an acidic environment. On the other hand, cytosolic alkalinization is known to stimulate glycolysis (65–67), which may support energy supply to Th9 cells. It is tempting to further speculate that the enhanced glycolysis in Th9 cells contributes to the deprivation of glucose for neighboring cancer cells. Clearly, additional experimental effort is required to define the exact role of Na+/H+ exchanger activity for Th9 cells survival and function.

In summary, we have shown that NHE1 is required for the development of Th9 cells. These data will help to understand the physiological function of Th9 cells and the metabolic reprogramming of Th9 cells.

Experimental Procedures

Mice Strains

C57BL/6 mice (8–12 weeks) were used for the experiments and kept in a conventional specific pathogen-free facility. Animal experiments were performed according to the EU Animals Scientific Procedures Act and the German law for the welfare of animals. The procedures were approved by the authorities of the state of Baden-Württemberg and the research has been reviewed and approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For each experiment 3–6 mice were used and data shown in each figure is representative of arithmetic means ± S.E. and numbers (n) of independent experiments.

Naive T Cells Isolation

To perform the Th differentiation or iTreg induction experiments, naive CD4+CD62Lhigh+CD25− T cells were isolated using magnetic bead selection from spleen and lymph nodes as described earlier (68, 69). To isolate the CD4+ T cells, the spleen and lymph nodes (inguinal, axillary, brachial, mediastinal, superficial cervical, mesenteric) were collected from the mice and macerated using a syringe plunger. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 600 × g at 4 °C for 5 min and the cell pellet was treated with RBC lysis buffer for 1 min and washed three times. After washing, the cells were kept on a roller at 4 °C (cold room) for 30 min in the presence of 40 μl/mouse antibody mixture containing anti-CD8, anti-MHC II, anti-CD11b, anti-CD16/32, anti-CD45R, and Ter-119 (Dynabeads® UntouchedTM Mouse CD4 cells kit, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Cells were then washed and Dynabeads® were added. The cells were incubated at 4 °C (cold room) for 30 min on a roller to deplete CD8+ T cells, B cells, NK cells, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, erythrocytes, and granulocytes and to isolate CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, to isolate CD4+CD25+ T cells, purified CD4+ T cells were incubated with 2 μl/mouse of biotinylated anti-CD25 (7D4 clone; BD Biosciences, UK) for 30 min on a roller (4 °C), washed, and kept for 15 min with 20 μl/mouse of streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Germany) for the indirect magnetic labeling of CD25+ T cells. Using MACS separation columns CD4+CD25+ T cells were positively selected and the remaining cells were CD4+CD25− T cells (18). To enrich naive CD4+CD62Lhigh+CD25− T cells from CD4+CD25− T cells, these cells were again incubated with 10 μl/mouse of biotinylated anti-CD62L (clone MEL-14; BD Biosciences) for 30 min on a roller (4 °C), washed, and kept for 15 min with 20 μl/mouse of streptavidin microbeads for the indirect magnetic labeling of CD62L+ T cells. Using MACS separation columns naive CD4+CD62Lhigh+CD25− T cells were positively selected. Remaining cells were CD4+CD62L−CD44+CD25− T cells. Purity of these cells was confirmed by flow cytometry. As a result, more than 90% cells were positive for naive T cells.

Th Cell Subsets Differentiation

Naive CD4+CD62Lhigh+CD25− T cells were activated in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies (eBioscience, Frankfurt, Germany) with a ratio of 1:2 anti-CD3:anti-CD28 (1:2 μg/ml, anti-CD3:anti-CD28) for Th1, Th2, and iTregs and 1:10 anti-CD3:anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml of anti-CD3: 10 μg/ml of anti-CD28) for Th9 and Th17. Briefly, T naive cells were differentiated into Th1 using 20 ng/ml of recombinant IL-12 (eBioscience), anti-IL-4 (5 μg/ml; eBioscience), Th2 using 20 ng/ml of recombinant-IL-4 (eBioscience), anti-IFN-γ (5 μg/ml; eBioscience), Th9 using 2.5 ng/ml of recombinant-TGF-β, 40 ng/ml of recombinant-IL-4, anti-IFN-γ (10 μg/ml), Th17 using 2.5 ng/ml of recombinant-TGF-β, 50 ng/ml of recombinant-IL-6 (eBioscience), anti-IFN-γ (5 μg/ml), anti-IL-4 (5 μg/ml), and anti-IL-2 (5 μg/ml; eBioscience) and iTregs using 2.5 ng/ml of recombinant-TGF-β, 5 ng/ml of recombinant-IL-2 (eBioscience), and cultured for 3–4 days (2, 3, 19, 47, 70). Cells were harvested at day 3 and used for intracellular staining for characterizing the Th cells using flow cytometry, q-RT-PCR, pHi, NHE1 activity, and immunoblotting experiments.

Intracellular pH (pHi) Measurement

Cytosolic pH (pHi) was measured in Th cell subsets as described previously (71) using pH-sensitive BCECF-AM dye (Invitrogen). Naive T cells were differentiated into Th cell subsets and after 3 days of differentiation various Th cell subsets were subjected to measurement of pHi with and without treatment. To measure the pHi and NHE1 activity of Th cells subsets, 300 μl of cells were collected and were fixed on a coverslip coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany), which was then placed in a chamber. Th cell subsets were co-incubated with 10 μm BCECF-AM for 15 min at 37 °C. Once the incubation was finished, the chamber was placed on the stage of an inverted phase-contrast microscope with the incident-light fluorescence illumination system (Axiovert 135, Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) with epifluorescence mode ×40 oil immersion objective (Zeiss). BCECF was successively excited at 490/10 and 440/10 nm, and the resultant fluorescent signal was monitored at 535/10 nm using an intensified charge-coupled device camera (Proxitronic, Germany) and specialized computer software (Metafluor, USA). Approximately 30–40 cells were outlined and monitored during the course of the measurements of BCECF fluorescence. The results from each cell were averaged and used for final data analysis.

High-K+/nigericin calibration technique was applied for converting intensity ratio (490/440) data into pHi values. The cells were perfused at the end of each experiment for 5 min with standard high-K+/nigericin (10 μg/ml) solution (pH 7.0). The intensity ratio data thus obtained were converted into pH values using the rmax, rmin, and pKa values previously generated from calibration experiments to establish a standard nonlinear curve (pH range 5 to 8.5) (72).

For acid loading, Th cell subsets were transiently exposed to a solution containing 20 mm NH4Cl leading to initial alkalinization of pHi due to entry of NH3 and binding of H+ to form NH4+. The acidification of pHi upon removal of ammonia allowed calculating the mean intrinsic buffering power (β) of the cell. Assuming that NH4+ and NH3 are in equilibrium in cytosolic and extracellular fluid and that ammonia leaves the cells as NH3,

where ΔpHi is the decrease of cytosolic pH (pHi) following ammonia removal and Δ[NH4+]i is the decrease of cytosolic NH4+ concentration, which is equal to [NH4+]i immediately before the removal of ammonia. The pK for NH4+/NH3 is 8.9 and at an extracellular pH (pHo) of 7.4 the NH4+ concentration in extracellular fluid ([NH4+]o) is 19.37 [20/(1 + 10pHo-pK)]. The intracellular NH4+ concentration ([NH4]i) was calculated from Equation 2.

The calculation of the buffer capacity required that NH4+ exits completely. After the initial decline, pHi indeed showed little further change in the absence of Na+, suggesting that there was no relevant further exit of NH4+. To calculate the ΔpH/min during re-alkalinization, a manual linear fit was placed over a narrow pH range with time which could be applied to all measured cells.

The solutions used in the pHi and NHE1 measurements were composed of (in mm) as described earlier (50): standard Hepes, 115 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, 32.2 Hepes; sodium-free Hepes, 132.8 NMDG-Cl, 3 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 KH2PO4, 32.2 Hepes, 10 mannitol, 10 glucose (for sodium-free ammonium chloride 10 mm NMDG and mannitol were replaced with 20 mm NH4Cl); high K+ for calibration, 105 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 32.2 Hepes, 10 mannitol, 5 μm nigericin. The pH of the solutions was titrated to 7.4 or 7.0 using HCl/NaOH, HCl/NMDG, and HCl/KOH, respectively, at 37 °C. In some cases, NHE1 inhibitor cariporide (10 μm; sc-337619A, Santa Cruz Biochemical, Santa Cruz, CA) and AKT1/2 (0.3 μm; A6730, Sigma) were used.

Surface and Intracellular Antibodies Staining

Th cell subsets were characterized by using surface and intracellular staining with relevant antibodies. In brief, Th cell subsets were stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 or 1 mg/ml of PMA (Sigma) and 1 mg/ml of ionomycin (Sigma) for 4 h and after 2 h of PMA + ionomycin treatment 1 μg/ml of brefeldin A (eBioscience) was added to the cultured cells for 2 h. After 4 h, cells were collected and used for surface and intracellular staining for various antibodies dependent on the experiment (anti-CD4-PerCP, anti-Foxp3-APC, and anti-IFN-γ-FITC; eBioscience, anti-IL-4-PE anti-IL-17A-PE; BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany, anti-IL-9-PE; BioLegend®, London, UK), and washed with PBS. Cells were fixed with Foxp3 fixation/permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) for intracellular staining and incubated for 30 min. After incubation, cells were washed with 1× permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) and intracellular monoclonal antibodies were added and incubated for an additional 30 min. Cells were washed again with permeabilization buffer and PBS was added to acquire the cells on flow cytometry (FACSCaliburTM, BD Bioscience).

q-RT-PCR

Total mRNA was isolated from different Th cell subsets (Th0, Th1, Th2, Th9, and Th17) and iTregs using miRNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as described by the manufacturer. 1 μg of mRNA was converted into cDNA using SuperScript III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, in 10-μl reactions, 10 ng of cDNA, 2× SYBR Green mastermix (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) and 250 nm primers (Sigma) were used for q-RT-PCR. q-RT-PCR run and data analysis was performed as described previously (21) for NHE-1 (Slc9α1) (F primer, 5′-TCGCCCAGATGACCACAATTT-3′ and R primer, 5′-GGGGATCACATGGAAACCTATCT-3′), Glut-1 (F primer, 5′-ATGGATCCCAGCAGCAAGAA-3′ and R primer, 5′-ACTCCTCAATAACCTTCTGGGG-3′), Hk2 (F primer, 5′-TGATCGCCTGCTTATTCACGG-3′ and R primer, 5′-AACCGCCTAGAAATCTCCAGA-3′), Tpi (F primer, 5′-CCAGGAAGTTCTTCGTTGGGG-3′ and R primer, 5′-CAAAGTCGATGTAAGCGGTGG-3′), Ldh2α (F primer, 5′-AACTTGGCGCTCTACTTGCT-3′ and R primer, 5′-GGACTTTGAATCTTTTGAGACCTTG-3′), Mct1 (F primer, 5′-AAAATGCCACCTGCGATTGG-3′ and R primer, 5′-TCACTGGTCGTTGCACTGAA-3′), Mct4 (F primer, 5′-CTGTTTGGCAGCACACCATT-3′ and R primer, 5′-GGCTGCTTTCACCAAGAACT-3′), Il-9 (F primer, 5′-CTCTCCGTCCCAACTGATGATT-3′ and R primer, 5′-AAAGGACGGACACGTGATGT-3′), Foxp3 (F primer, 5′-GGTACACCCAGGAAAGACAG-3′ and R primer, 5′-ATCCAGGAGATGATCTGCTTG-3′), 18S rRNA (F primer, 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′ and R primer, 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′), and Gapdh (F primer, 5′-CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGT-3′ and R primer, 5′-TTGATGGCAACAATCTCCAC-3′) using universal cycling conditions (95 °C for 3 min, 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 1 min for 40 cycles followed by melting curve analysis).

Immunoblotting

Naive T cells were differentiated into Th0, Th1, Th2, Th9, Th17, and iTregs from WT mice. After 48 h of incubation, Th cell subsets and iTregs were washed once with PBS and equal amounts of H2O and 2× Laemmli's buffer added for cell lysis. Proteins were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and stored at −20 °C. Sample proteins were loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and run for 80–120 V for 120 min. Proteins were electrotransferred onto membranes. Membranes were probed with the indicated primary antibodies for NHE1 (1:1000 NHE1 rabbit antibody number GTX85047 from Genetex®, Irvine, CA), Akt (number 4691), AktS473 (number 4060), AktT308 (number 13038), Rictor (number 2114), and mTOR (number 2983) (1:1000 dilution and all from Cell Signaling Technology, Leiden, The Netherlands), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology). Membranes were washed and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (WesternBright ECL; Biozym® Scientific GmbH, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany) and data were analyzed using ImageJ software.

siRNA Transfection of T Cells

Naive T cells were transfected with siRNA-control and siRNA-NHE1 using DharmaFECT3 transfection reagent (GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, LA) as recommended by the manufacturer's guidelines. Briefly, naive T cells were washed 3 times with PBS to remove any residual serum and antibiotics from the cells and 0.75–1 × 106 cells/well cultured in the presence of antibiotic free media in 24-well plate coated with anti-CD3:anti-CD28. Final concentration of 200 nm non-targeting siRNA-control and siRNA-NHE1 was added to 500 μl of media and cells were incubated with Th9 differentiating conditions as described earlier. Cells were further incubated for 4 days and stained for IL-9/Foxp3 antibodies.

ATP Measurement

Naive CD4+ T cells were differentiated into Th9 cells and also incubated with cariporide (10 μm). Intracellular ATP measurement by luciferase-based assay (ATP Bioluminescence Assay kit CLS II, Roche Diagnostics and Sigma) was performed as described earlier (73). Data were normalized with Th0 cells, performed in triplicate, and relative ATP levels estimated.

Statistical Analysis

Prism software (GraphPad software, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Student's t test was used for determination of significance. Flow cytometry data were analyzed by Flowjo (Treestar). Figures were made in Excel and GraphPad Prism software. ImageJ was used for Western blot data analysis. p values of equal or less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Author Contributions

Y. S., K. S. L., and F. L. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. Y. S. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 1 and 3–6. Y. Z. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 2 and 4–6. X. S., S. Z., and M. S. S. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 1 and 3–6. A. T. U. provided technical assistance and contributed to the preparation of figures. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the meticulous preparation of the manuscript by Tanja Loch and Lejla Subasic. We also gratefully acknowledge the careful reading of the manuscript by Dr. Bradley S. Cobb, The Royal Veterinary College, London, UK.

This work was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft LA 315 (to F. L.), EMBO Long Term Postdoctoral Fellowship ATLF 20-2013 (to M. S. S.), and China Scholarship Council (CSC), China Ph.D. studentships (to Y. Z., X. S., and S. Z.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the content of this article.

- Th

- T helper

- BCECF-AM

- 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein-acetoxymethyl ester

- Tregs

- regulatory T cells

- GITR

- glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related

- iTregs

- induced Tregs

- OXPHOS

- oxidative phosphorylation

- NHE

- Na+/H+ exchanger

- q-RT

- quantitative RT

- TPI

- triose-phosphate isomerase

- MCT

- monocarboxylic acid transporter

- mTOR

- mechanistic target of rapamycin.

References

- 1. Zhu J., and Paul W. E. (2010) Heterogeneity and plasticity of T helper cells. Cell Res. 20, 4–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou L., Chong M. M., and Littman D. R. (2009) Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity 30, 646–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kudo M., Ishigatsubo Y., and Aoki I. (2013) Pathology of asthma. Front. Microbiol. 4, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Awasthi A., and Kuchroo V. K. (2009) Th17 cells: from precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int. Immunol. 21, 489–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bettelli E., Carrier Y., Gao W., Korn T., Strom T. B., Oukka M., Weiner H. L., and Kuchroo V. K. (2006) Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korn T., Mitsdoerffer M., Croxford A. L., Awasthi A., Dardalhon V. A., Galileos G., Vollmar P., Stritesky G. L., Kaplan M. H., Waisman A., Kuchroo V. K., and Oukka M. (2008) IL-6 controls Th17 immunity in vivo by inhibiting the conversion of conventional T cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18460–18465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dardalhon V., Awasthi A., Kwon H., Galileos G., Gao W., Sobel R. A., Mitsdoerffer M., Strom T. B., Elyaman W., Ho I. C., Khoury S., Oukka M., and Kuchroo V. K. (2008) IL-4 inhibits TGF-β-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-β, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(−) effector T cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1347–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dardalhon V., Collins M., and Kuchroo V. K. (2015) Physical attraction of Th9 cells is skin deep. Ann. Transl. Med. 3, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaplan M. H., Hufford M. M., and Olson M. R. (2015) The development and in vivo function of T helper 9 cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 295–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmitt E. G., Haribhai D., Williams J. B., Aggarwal P., Jia S., Charbonnier L. M., Yan K., Lorier R., Turner A., Ziegelbauer J., Georgiev P., Simpson P., Salzman N. H., Hessner M. J., Broeckel U., Chatila T. A., and Williams C. B. (2012) IL-10 produced by induced regulatory T cells (iTregs) controls colitis and pathogenic ex-iTregs during immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 189, 5638–5648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kara E. E., Comerford I., Bastow C. R., Fenix K. A., Litchfield W., Handel T. M., and McColl S. R. (2013) Distinct chemokine receptor axes regulate Th9 cell trafficking to allergic and autoimmune inflammatory sites. J. Immunol. 191, 1110–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kerzerho J., Maazi H., Speak A. O., Szely N., Lombardi V., Khoo B., Geryak S., Lam J., Soroosh P., Van Snick J., and Akbari O. (2013) Programmed cell death ligand 2 regulates TH9 differentiation and induction of chronic airway hyperreactivity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 1048–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerlach K., Hwang Y., Nikolaev A., Atreya R., Dornhoff H., Steiner S., Lehr H. A., Wirtz S., Vieth M., Waisman A., Rosenbauer F., McKenzie A. N., Weigmann B., and Neurath M. F. (2014) TH9 cells that express the transcription factor PU.1 drive T cell-mediated colitis via IL-9 receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat. Immunol. 15, 676–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horka H., Staudt V., Klein M., Taube C., Reuter S., Dehzad N., Andersen J. F., Kopecky J., Schild H., Kotsyfakis M., Hoffmann M., Gerlitzki B., Stassen M., Bopp T., and Schmitt E. (2012) The tick salivary protein sialostatin L inhibits the Th9-derived production of the asthma-promoting cytokine IL-9 and is effective in the prevention of experimental asthma. J. Immunol. 188, 2669–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaplan M. H. (2013) Th9 cells: differentiation and disease. Immunol. Rev. 252, 104–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Licona-Limón P., Henao-Mejia J., Temann A. U., Gagliani N., Licona-Limón I., Ishigame H., Hao L., Herbert D. R., and Flavell R. A. (2013) Th9 cells drive host immunity against gastrointestinal worm infection. Immunity 39, 744–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lu Y., Hong S., Li H., Park J., Hong B., Wang L., Zheng Y., Liu Z., Xu J., He J., Yang J., Qian J., and Yi Q. (2012) Th9 cells promote antitumor immune responses in vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 122, 4160–4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Niedbala W., Besnard A. G., Nascimento D. C., Donate P. B., Sonego F., Yip E., Guabiraba R., Chang H. D., Fukada S. Y., Salmond R. J., Schmitt E., Bopp T., Ryffel B., and Liew F. Y. (2014) Nitric oxide enhances Th9 cell differentiation and airway inflammation. Nat. Commun. 5, 4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perumal N. B., and Kaplan M. H. (2011) Regulating Il9 transcription in T helper cells. Trends Immunol. 32, 146–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Purwar R., Schlapbach C., Xiao S., Kang H. S., Elyaman W., Jiang X., Jetten A. M., Khoury S. J., Fuhlbrigge R. C., Kuchroo V. K., Clark R. A., and Kupper T. S. (2012) Robust tumor immunity to melanoma mediated by interleukin-9-producing T cells. Nat. Med. 18, 1248–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soroosh P., and Doherty T. A. (2009) Th9 and allergic disease. Immunology 127, 450–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Végran F., Apetoh L., and Ghiringhelli F. (2015) Th9 cells: a novel CD4 T-cell subset in the immune war against cancer. Cancer Res. 75, 475–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Veldhoen M., Uyttenhove C., van Snick J., Helmby H., Westendorf A., Buer J., Martin B., Wilhelm C., and Stockinger B. (2008) Transforming growth factor-β ”reprograms“ the differentiation of T helper 2 cells and promotes an interleukin 9-producing subset. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1341–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goswami R., Jabeen R., Yagi R., Pham D., Zhu J., Goenka S., and Kaplan M. H. (2012) STAT6-dependent regulation of Th9 development. J. Immunol. 188, 968–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruhn S., Barrenäs F., Mobini R., Andersson B. A., Chavali S., Egan B. S., Hovig E., Sandve G. K., Langston M. A., Rogers G., Wang H., and Benson M. (2012) Increased expression of IRF4 and ETS1 in CD4+ cells from patients with intermittent allergic rhinitis. Allergy 67, 33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Végran F., Berger H., Boidot R., Mignot G., Bruchard M., Dosset M., Chalmin F., Rébé C., Dérangère V., Ryffel B., Kato M., Prévost-Blondel A., Ghiringhelli F., and Apetoh L. (2014) The transcription factor IRF1 dictates the IL-21-dependent anticancer functions of T9 cells. Nat. Immunol. 15, 758–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liao W., Spolski R., Li P., Du N., West E. E., Ren M., Mitra S., and Leonard W. J. (2014) Opposing actions of IL-2 and IL-21 on Th9 differentiation correlate with their differential regulation of BCL6 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 3508–3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jabeen R., Goswami R., Awe O., Kulkarni A., Nguyen E. T., Attenasio A., Walsh D., Olson M. R., Kim M. H., Tepper R. S., Sun J., Kim C. H., Taparowsky E. J., Zhou B., and Kaplan M. H. (2013) Th9 cell development requires a BATF-regulated transcriptional network. J. Clin. Investig. 123, 4641–4653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xiao X., Shi X., Fan Y., Zhang X., Wu M., Lan P., Minze L., Fu Y. X., Ghobrial R. M., Liu W., and Li X. C. (2015) GITR subverts Foxp3+ Tregs to boost Th9 immunity through regulation of histone acetylation. Nat. Commun. 6, 8266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim I. K., Kim B. S., Koh C. H., Seok J. W., Park J. S., Shin K. S., Bae E. A., Lee G. E., Jeon H., Cho J., Jung Y., Han D., Kwon B. S., Lee H. Y., Chung Y., and Kang C. Y. (2015) Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related protein co-stimulation facilitates tumor regression by inducing IL-9-producing helper T cells. Nat. Med. 21, 1010–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singh Y., Garden O. A., Lang F., and Cobb B. S. (2016) miRNAs regulate T cell production of IL-9 and identify hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) as an important regulator of Th9 and Treg differentiation. Immunology 149, 74–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buck M. D., O'Sullivan D., and Pearce E. L. (2015) T cell metabolism drives immunity. J. Exp. Med. 212, 1345–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Newton R., Priyadharshini B., and Turka L. A. (2016) Immunometabolism of regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 17, 618–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Palmer C. S., Ostrowski M., Balderson B., Christian N., and Crowe S. M. (2015) Glucose metabolism regulates T cell activation, differentiation, and functions. Front. Immunol. 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gerriets V. A., Kishton R. J., Nichols A. G., Macintyre A. N., Inoue M., Ilkayeva O., Winter P. S., Liu X., Priyadharshini B., Slawinska M. E., Haeberli L., Huck C., Turka L. A., Wood K. C., Hale L. P., et al. (2015) Metabolic programming and PDHK1 control CD4+ T cell subsets and inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 125, 194–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harguindey S., Arranz J. L., Polo Orozco J. D., Rauch C., Fais S., Cardone R. A., and Reshkin S. J. (2013) Cariporide and other new and powerful NHE1 inhibitors as potentially selective anticancer drugs: an integral molecular/biochemical/metabolic/clinical approach after one hundred years of cancer research. J. Transl. Med. 11, 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chiche J., Brahimi-Horn M. C., and Pouysségur J. (2010) Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: a common feature in cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 771–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Odunewu A., and Fliegel L. (2013) Acidosis-mediated regulation of the NHE1 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger in renal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 305, F370–F381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Putney L. K., and Barber D. L. (2004) Expression profile of genes regulated by activity of the Na-H exchanger NHE1. BMC Genomics 5, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koivusalo M., Kapus A., and Grinstein S. (2009) Sensors, transducers, and effectors that regulate cell size and shape. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6595–6599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paroutis P., Touret N., and Grinstein S. (2004) The pH of the secretory pathway: measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology 19, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. De and Vito P. (2006) The sodium/hydrogen exchanger: a possible mediator of immunity. Cell. Immunol. 240, 69–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fliegel L. (2005) The Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bluestone J. A., Mackay C. R., O'Shea J. J., and Stockinger B. (2009) The functional plasticity of T cell subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 811–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alexander R. T., Jaumouillé V., Yeung T., Furuya W., Peltekova I., Boucher A., Zasloff M., Orlowski J., and Grinstein S. (2011) Membrane surface charge dictates the structure and function of the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger. EMBO J. 30, 679–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stock C., and Schwab A. (2006) Role of the Na/H exchanger NHE1 in cell migration. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 187, 149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chatterjee S., Schmidt S., Pouli S., Honisch S., Alkahtani S., Stournaras C., and Lang F. (2014) Membrane androgen receptor sensitive Na+/H+ exchanger activity in prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 588, 1571–1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Meima M. E., Webb B. A., Witkowska H. E., and Barber D. L. (2009) The sodium-hydrogen exchanger NHE1 is an Akt substrate necessary for actin filament reorganization by growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26666–26675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu K. L., Khan S., Lakhe-Reddy S., Jarad G., Mukherjee A., Obejero-Paz C. A., Konieczkowski M., Sedor J. R., and Schelling J. R. (2004) The NHE1 Na+/H+ exchanger recruits ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins to regulate Akt-dependent cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26280–26286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou Y., Pasham V., Chatterjee S., Rotte A., Yang W., Bhandaru M., Singh Y., and Lang F. (2015) Regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger in dendritic cells by Akt1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 36, 1237–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mills G. B., Cheung R. K., Cragoe E. J. Jr., Grinstein S., and Gelfand E. W. (1986) Activation of the Na+/K+ antiport is not reuired for lectin-induced proliferation of human T lymphoyctes. J. Immunol. 136, 1150–1154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chang C. P., Wang S. W., Huang Z. L., Wang O. Y., Huang M. I., Lu L. M., Tarng D. C., Chien C. H., and Chien E. J. (2010) Non-genomic rapid inhibition of Na+/H+-exchange 1 and apoptotic immunosuppression in human T cells by glucocorticoids. J. Cell. Physiol. 223, 679–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chien E. J., Liao C. F., Chang C. P., Pu H. F., Lu L. M., Shie M. C., Hsieh D. J., and Hsu M. T. (2007) The non-genomic effects on Na+/H+-exchange 1 by progesterone and 20α-hydroxyprogesterone in human T cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 211, 544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lacroix J., Poët M., Maehrel C., and Counillon L. (2004) A mechanism for the activation of the Na/H exchanger NHE-1 by cytoplasmic acidification and mitogens. EMBO Rep. 5, 91–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liszewski M. K., Kolev M., Le Friec G., Leung M., Bertram P. G., Fara A. F., Subias M., Pickering M. C., Drouet C., Meri S., Arstila T. P., Pekkarinen P. T., Ma M., Cope A., Reinheckel T., et al. (2013) Intracellular complement activation sustains T cell homeostasis and mediates effector differentiation. Immunity 39, 1143–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Qadri S. M., Su Y., Cayabyab F. S., and Liu L. (2014) Endothelial Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 participates in redox-sensitive leukocyte recruitment triggered by methylglyoxal. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 13, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Abu Jawdeh B. G., Khan S., Deschênes I., Hoshi M., Goel M., Lock J. T., Shinlapawittayatorn K., Babcock G., Lakhe-Reddy S., DeCaro G., Yadav S. P., Mohan M. L., Naga Prasad S. V., Schilling W. P., Ficker E., and Schelling J. R. (2011) Phosphoinositide binding differentially regulates NHE1 Na+/H+ exchanger-dependent proximal tubule cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42435–42445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nagai S., Kurebayashi Y., and Koyasu S. (2013) Role of PI3K/Akt and mTOR complexes in Th17 cell differentiation. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1280, 30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee K., Gudapati P., Dragovic S., Spencer C., Joyce S., Killeen N., Magnuson M. A., and Boothby M. (2010) Mammalian target of rapamycin protein complex 2 regulates differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cell subsets via distinct signaling pathways. Immunity 32, 743–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pierau M., Engelmann S., Reinhold D., Lapp T., Schraven B., and Bommhardt U. H. (2009) Protein kinase B/Akt signals impair Th17 differentiation and support natural regulatory T cell function and induced regulatory T cell formation. J. Immunol. 183, 6124–6134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Haxhinasto S., Mathis D., and Benoist C. (2008) The AKT-mTOR axis regulates de novo differentiation of CD4+Foxp3+ cells. J. Exp. Med. 205, 565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M., and Pouyssegur J. (1997) Molecular physiology of vertebrate Na+/H+ exchangers. Physiol. Rev. 77, 51–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang Y., Bi Y., Chen X., Li C., Li Y., Zhang Z., Wang J., Lu Y., Yu Q., Su H., Yang H., and Liu G. (2016) Histone deacetylase SIRT1 negatively regulates the differentiation of interleukin-9-Producing CD4+ T cells. Immunity 44, 1337–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cairns R. A. (2015) Drivers of the Warburg phenotype. Cancer J. 21, 56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Boiteux A., and Hess B. (1981) Design of glycolysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 293, 5–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Heinrich R., Meléndez-Hevia E., Montero F., Nuño J. C., Stephani A., and Waddell T. G. (1999) The structural design of glycolysis: an evolutionary approach. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 27, 294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tennant D. A., Durán R. V., and Gottlieb E. (2010) Targeting metabolic transformation for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Singh Y., Chen H., Zhou Y., Föller M., Mak T. W., Salker M. S., and Lang F. (2015) Differential effect of DJ-1/PARK7 on development of natural and induced regulatory T cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 17723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Singh Y., Dyson J., and Garden O. A. (2011) Use of SNARF-1 to measure murine T cell proliferation in vitro and its application in a novel regulatory T cell suppression assay. Immunol. Lett. 140, 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Singh Y., Garden O. A., Lang F., and Cobb B. S. (2015) MicroRNA-15b/16 enhances the induction of regulatory T cells by regulating the expression of Rictor and mTOR. J. Immunol. 195, 5667–5677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Salker M. S., Zhou Y., Singh Y., Brosens J., and Lang F. (2015) LeftyA sensitive cytosolic pH regulation and glycolytic flux in Ishikawa human endometrial cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 460, 845–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rotte A., Pasham V., Eichenmüller M., Mahmud H., Xuan N. T., Shumilina E., Götz F., and Lang F. (2010) Effect of bacterial lipopolysaccharide on Na+/H+ exchanger activity in dendritic cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 26, 553–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hosseinzadeh Z., Honisch S., Schmid E., Jilani K., Szteyn K., Bhavsar S., Singh Y., Palmada M., Umbach A. T., Shumilina E., and Lang F. (2015) The role of Janus kinase 3 in the regulation of Na+/K+-ATPase under energy depletion. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 36, 727–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]