Abstract

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is a rare and benign inflammatory disorder that predominantly affects the stomach and the small intestine. The disease is divided into three subtypes (mucosal, muscular and serosal) according to klein’s classification, and its manifestations are protean, depending on the involved intestinal segments and layers. Hence, accurate diagnosis of EGE poses a significant challenge to clinicians, with evidence of the following three criteria required: Suspicious clinical symptoms, histologic evidence of eosinophilic infiltration in the bowel and exclusion of other pathologies with similar findings. In this review, we designed and applied an algorithm to clarify the steps to follow for diagnosis of EGE in clinical practice. The management of EGE represents another area of debate. Prednisone remains the mainstay of treatment; however the disease is recognized as a chronic disorder and one that most frequently follows a relapsing course that requires maintenance therapy. Since prolonged steroid treatment carries of risk of serious adverse effects, other options with better safety profiles have been proposed; these include budesonide, dietary restrictions and steroid-sparing agents, such as leukotriene inhibitors, azathioprine, anti-histamines and mast-cell stabilizers. Single cases or small case series have been reported in the literature for all of these options, and we provide in this review a summary of these various therapeutic modalities, placing them within the context of our novel algorithm for EGE management according to disease severity upon presentation.

Keywords: Eosinophilic, Gastroenteritis, Diagnosis, Management, Algorithm, Review

Core tip: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is a heterogeneous inflammatory bowel disorder, which commonly follows a chronic and relapsing course. To date, only single cases or small case series provide insights into its diagnosis and management. This manuscript reviews the different diagnostic tools utilized in practice and provides an algorithm for diagnosis. It also provides a summary of the therapeutic modalities applied in EGE management, which are placed within the context of an algorithm for systematic application of the different strategies according to the initial disease severity.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is a rare inflammatory disorder characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the intestinal wall. Since its first description, about 8 decades ago, reports of subsequent cases have revealed a widely variable and heterogeneous profile of physical manifestations. Studies from the United States have found a prevalence ranging between 8.4 and 28 per 100000[1,2], with a slightly increasing incidence over the past 50 years[3]; additionally, the disease is well known to be more common among the pediatric population, with afflicted adults typically between the 3rd and 5th decade of life[4]. Intriguingly, the more recent estimates of EGE in the United States have found a shift from male preponderance[4,5] to female predominance[2]. Higher socioeconomic status, Caucasian race and excess weight may be risk factors of EGE[3], and a possible hereditary component (genetic factor) is suggested by reports of familial cases[6].

Concomitant allergic disorders, including asthma, rhinitis, eczema and drug or food intolerances, are present in 45% to 63% of the reported EGE cases[1,3]; moreover, 64% of reported cases include a family history of atopic diseases[7]. Some studies have found an association with other autoimmune conditions, such as celiac disease[8], ulcerative colitis[9] and systemic lupus erythematosus[10]. These data collectively suggest that EGE may result from immune dysregulation in response to an allergic reaction; yet, a triggering allergen is not always identified. Indeed, about 50% of EGE cases involving the alimentary tract have been detected by allergy testing to address a suspected food allergy[3]. Other environmental factors, such as parasitic infestation and drugs, may act as predisposing agents as well[11].

Both immunoglobulin E (IgE) dependent and delayed TH2 cell-mediated allergic mechanisms have been demonstrated to be involved in the pathogenesis of EGE. Interleukin 5 (IL-5) has also been shown to play an essential role in the expansion of eosinophils and their recruitment to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the mechanism underlying the pathogenic hallmark of EGE. Chemokines, namely eotaxin 1 and α4β7 integrin, are also known to contribute to eosinophilic homing inside the intestinal wall. Other mediators-most notably IL-3, IL-4, IL-13, leukotrienes and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha-act to enhance eosinophilic trafficking and have been proposed to help in prolonging lymphocytic and eosinophilic activity[11-13]. Many of these immune-related molecules are currently under consideration as potential targets for molecular therapy of EGE.

Once recruited to the GI tract, the activated eosinophils induce a significant inflammatory response by secreting a variety of mediators including the cytotoxic granules that lead to structural damage in the infiltrated intestinal layers[12]. Thus, EGE can affect any GI segment, but reports have shown that the small intestine and stomach are the most predominant areas[4]. In clinical practice, the Klein classification system[14] is used to categorize the disease type according to the involved intestinal layer; the 3 Klein categories are mucosal, muscular and serosal. The mucosal layer is the most commonly affected, as has been reported in the majority of case series in the literature, with prevalence ranging between 57% in older estimates[4] and 88% to 100% in more recent estimates[3,15]. Furthermore, the muscular and serosal types are commonly associated with concomitant mucosal eosinophilic infiltration, which raises the hypothesis of centrifugal disease progression from the deep mucosa toward the muscular and serosal layers[3].

DIAGNOSIS

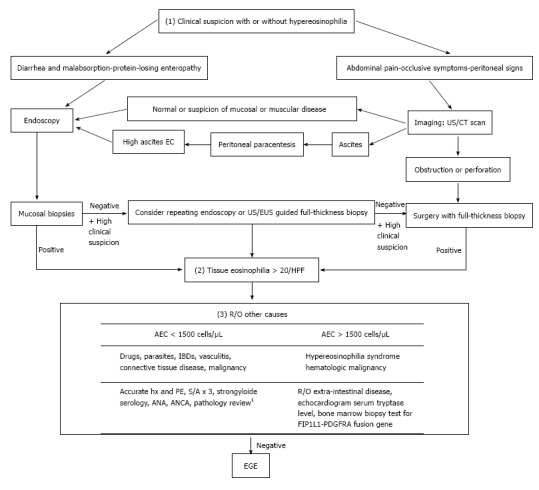

Diagnosis of EGE requires three criteria, namely: (1) presence of GI symptoms; (2) histologic evidence of eosinophilic infiltration in one or more areas of the GI tract; and (3) exclusion of other causes of tissue eosinophilia[16] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm for eosinophilic gastroenteritis diagnosis. 1Histologic ascertainment for absence of malignant cells or findings suggestive of IBD, connective tissue diseases or vasculitis. AEC: Absolute eosinophilic count; ANA: Anti-nuclear antibody; ANCA: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; EC: Eosinophilic count; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; Hx: History; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; PE: Physical examination; S/A: Stool analysis; US: Ultrasound; EGE: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

While EGE manifestations vary depending on the affected GI layer, abdominal pain is the predominant presenting symptom among all 3 of the disease types[5]. Involvement of the mucosal layer may cause diarrhea, vomiting, protein-losing enteropathy and malabsorption, which in turn can manifest as anemia, hypoalbuminemia and weight loss. Involvement of the muscular layer can lead to a partial or total intestinal obstruction. Involvement of the serosal layer may cause peritoneal irritation, which can lead to ascites, peritonitis and perforation in more severe cases; intestinal intussusception may occur in the serosal type as well[17]. An additional manifestation of the disease, peripapillary duodenal disease, which is secondary to the eosinophilic infiltration of the peripapillary duodenal region, might result in pancreatitis and biliary obstruction[18,19].

Some laboratory findings are sufficient to raise suspicion of EGE, although they are not adequate for an EGE diagnosis. About 70% of cases present with peripheral eosinophilia[4,20] and EGE cases with deep serosal involvement frequently have higher absolute eosinophilic counts (AECs)[20], the latter of which may also be associated with greater risk of relapse[20]. Elevated IgE is reportedly present in about two-thirds of EGE cases[5] and a trend of increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) values has been observed. Finally, some reports of EGE cases have demonstrated that peritoneal fluid analysis shows exudative fluid with a net eosinophilic predominance reaching about 90% of white blood cells (WBCs)[21].

Following assessment of the patient’s initial presentation, the next step toward diagnosis will require either endoscopy or imaging studies (Figure 1). Endoscopic findings suggestive of EGE include normal aspect, erythematous friable mucosa, ulcers, pseudo-polyps and polyps[22,23], none of which are sensitive or specific for diagnosis of the disease. Thus, findings from endoscopic biopsies can play an essential role in diagnosis, as evidenced by the reported detection rate of 80% for this examination modality[24]. Unfortunately, however, the patchy distribution profile of the disease necessitates multiple biopsies, at least 5 or 6, be obtained from both endoscopically abnormal and normal mucosa, as the latter may mask about 60% of histologically proven disease[15]. Even in cases of negative initial biopsies, but with an otherwise high suspicion index, repeat endoscopy may be useful. Endoscopic ultrasound is also a useful tool for assessing muscular and sub-serosal involvement, as it facilitates access to these tissues for biopsy via fine needle aspiration[25,26].

Imaging studies are another diagnostic modality that has proven useful. In addition to guiding biopsy taking efforts, ultrasound can detect ascites and intestinal wall thickening[27]. Computed tomography (CT) scan can detect diffuse thickening of mucosal folds, intestinal wall thickening, ascites and obstruction. Two other scanographic signs that may appear secondary to bowel wall layering are the “Halo sign” and the “araneid-limb-like sign”, both of which can aid in differentiating between an inflammatory and a neoplastic lesion[28,29] and in ruling out extra-intestinal pathologies. The imaging modality of Tc-99m hexamethylpropyleneamineoxime (HMPAO)-labeled WBC scintigraphy provides a topographic description of the disease and allows for monitoring of therapeutic response[30]; however, this technology is not widely available and is not yet established as a reliable diagnostic tool for EGE.

While many tools can aid in obtainment of biopsies, the preferred method is still surgery, which provides a full thickness specimen for comprehensive pathology and the most accurate diagnosis, particularly for the muscular and serosal disease types[31].

Histologic examination remains the cornerstone of diagnosis. An absolute eosinophil count of at least 20 eosinophils/hpf has been set in most reports[7,23] as the threshold for fulfilling the second diagnostic criterion. The presence of intraepithelial eosinophils and eosinophils in the Peyer’s patches[32], as well as of extracellular deposition of eosinophil major basic proteins (MBPs)[33], favor development of EGE. The latter finding, in particular, reflects the degree of degranulation in activated eosinophils, which is directly linked to greater structural damage[6]. Observation of villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia or abscesses and epithelial degenerative/regenerative changes are also common findings of EGE. As such, some researchers have emphasized the importance of a subjective histological analysis, in addition to the eosinophilic count, as an important aspect for diagnosis[34].

Accordingly, we suggest dividing the disease into four classifications - mild, moderate, severe and complicated - based upon the initial clinical manifestations, initial laboratory findings, and severity of GI structural damage as assessed by radiologic, endoscopic and histologic examinations (Table 1)[34-39].

Table 1.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis severity upon presentation

| Initial findings | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Complicated |

| Clinical | ||||

| Abdominal pain | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Vomiting | Mild (< 3/d) | Moderate (3-7/d) | protracted (> 8/d) | |

| Diarrhea | < 6 BM/d | 6-12 BM/d | > 12 BM/d | |

| Weight loss1[35] | Non-significant | 1 wk 1%-2% 1 mo 5% 3 mo 7.5% 6 mo 10% | 1 wk > 2% 1 mo > 5% 3 mo > 7.5% 6 mo > 10% | |

| Laboratory | ||||

| Alb, g/dL | > 3 | 2.5-3 | < 2.5 | |

| HB, g/dL[36] | 9.5-11 | 8-9.5 | < 8 | |

| AEC, cells/μL[37] | < 1500 | 1500-5000 | > 5000 | |

| Radiologic | ||||

| Ascites | None or mild | Moderate volume | Large volume | Perforation |

| Intestinal wall thickening[38] | Mild (1-2 cm) Focal (< 10 cm) | Marked (> 2 cm), segmental (10-30 cm) | Sub-occlusion, extensive (> 30 cm) | Occlusion Intussusception |

| Endoscopy | ||||

| Mucosal inflammation[39] | Normal or mild erythema | Moderate | Severe with pseudo-polyps/bleeding | GOO Pyloric stenosis |

| Histology | ||||

| Structural damage2[34] | Minimal | Moderate | Severe |

Percent weight change = [(usual weight - actual weight)/(usual weight)] × 100

Subjective assessment by expert pathologist. AEC: Absolute eosinophilic count; Alb: Albumin; GOO: Gastric outlet obstruction; HB: Hemoglobin.

Following confirmation of eosinophilic infiltration to the GI tract, the exclusion of other possible causes of the initial clinical presentation is crucial for diagnosis of EGE (Figure 1). These other possible causes include parasitic infections (i.e., Strongyloides, Ascaris, Ancylostoma, Anisakis, Capillaria, Toxicara, Trichiura and Trichinella spp), drugs, vasculitis (i.e., Churg-Strauss syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa), connective tissue diseases, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), celiac disease, lymphoma, leukemia and mastocytosis. Furthermore, ruling out of the hypereosinophilic syndrome is of special value as it is a myeloproliferative disorder, characterized by idiopathic high peripheral eosinophilic count of > 1500 eos/hpf persisting for > 6 mo and having severe systemic implications due to its multisystem involvement, including heart, central nervous system, skin, lungs, liver and kidneys in addition to the GI tract[34,40].

It is also important to perform a food allergy evaluation in all patients with suspected EGE. Both IgE dependent (specific IgE and skin prick) and non-IgE TH2 dependent (skin patch) allergy tests may aid in identification of the specific allergen related to a case. However, these tests lack both sensitivity (missing about 40% of causative agents) and specificity (capable of overlapping detection of up to 14 allergens in some cases)[41]. A combination of both testing types, however, might enhance their overall predictive value for identifying the EGE-provoking agents[42].

MANAGEMENT

Although spontaneous remission reportedly occurs in around 30% to 40% of EGE cases[20,43], most patients require ongoing treatment. Many therapeutic options have been suggested, including dietary considerations, steroids, leukotrienes inhibitors and mast cells stabilizers. All of these treatment approaches have been described in small case series, but no randomized controlled or comparative trials have been published in the publicly available literature to describe the efficacies of different treatments or predictors of response to one or another option. Thus, no clear, systematic and practical strategy has been put forth for healthcare teams to follow in their management of EGE cases.

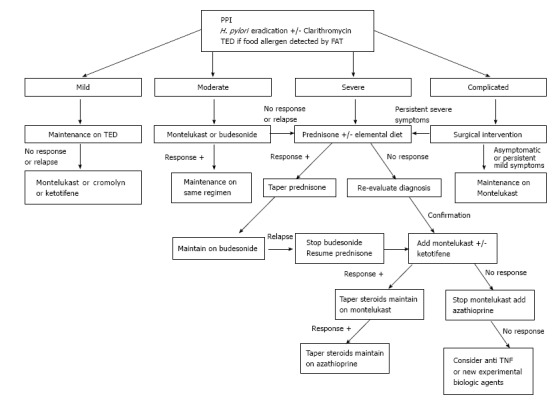

EGE is recognized as a chronic inflammatory disorder. Pineton de Chambrun et al[20] described three different long-term progression patterns: Non-relapsing disease (42%), commonly seen in patients with the serosal type; relapsing-remitting disease (37%), occurring primarily in patients with the muscular type; and chronic (persistent) disease (21%), predominantly observed in patients with the mucosal type. As mentioned above, a high AEC at diagnosis was found to be an independent predictor of relapses, as was extensive intestinal involvement. Some case series have found higher relapsing rates of 60% to 80%[7,26,44], while others have noted a possible association between younger age (under 20-year-old) and disease recurrence[24]. Unfortunately, research has not identified any other predictors of EGE disease evolution. Thus, it is worth contemplating maintenance treatment for patients after the initial induction phase has passed (Figure 2), taking into consideration the safety profile of the drug in use. It is important to remember, however, that the duration of such maintenance therapy cannot be predicted at this point.

Figure 2.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis management based on initial disease severity. Anti-TNF: Anti-tumor necrosis factor; FAT: Food allergy testing; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; TED: Targeted elimination diet.

TREATMENT MODALITIES

Proton pump inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment has been shown to improve the extent of duodenal eosinophilic infiltration in a patient with EGE, and the mechanism has been hypothesized to involve blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 activity[45]. H. pylori eradication has also been postulated as capable of inducing a cure of EGE disease[46]. The antibiotic clarithromycin, which is commonly used to treat H. pylori-related ulcers, is also known to have immunomodulatory effect, whereby its actions cause inhibition of T cell proliferation and induction of eosinophil apoptosis; these mechanistic actions in the immune system have led to clarithromycin being applied as maintenance therapy for patients with steroid dependent EGE who are in remission[47].

Dietary therapy

Many dietary strategies have been proposed for management of EGE based on results from food allergy tests. In general, when a limited number of food allergens is detected, patients should be maintained on a “targeted elimination diet” (TED). When many or no allergens are identified, the more aggressive “empiric elimination diet” or “elemental diet” can be used. Lucendo et al[48] investigated dietary treatment efficacy in EGE through a systematic review and found significant improvement in most cases, especially in those who undertook the elemental diet, which induced clinical remission in > 75% of cases. However, the validity of such a high efficacy rate was questionable since no confirmation of histologic response was available for the majority of cases included in the review. On the other hand, the authors noted that dietary measures were predominantly considered in the setting of mucosal disease, which is well known to be associated with food allergy, while the efficacy in muscular and serosal types, which show weaker linkage to food allergy[4], was only rarely reported. In addition, patients’ adherence and tolerability to such strategies remain an important drawback, especially when empiric elimination or elemental diets are used.

Thus, we suggest the TED for all EGE patients (Figure 2) who show few food allergens upon testing. The overall data in the literature is insufficient to recommend empiric and total elimination diets in routine management; however, an elemental diet can be used initially as adjunct treatment for severe cases.

Prednisone

Prednisone remains the mainstay for induction of remission of EGE. While most of the case series reported have shown a response rate to prednisone (up to 90%)[3,49], the most recent reports showed remarkably lower values (only 50%)[7]. This steroid acts by inducing eosinophil apoptosis and inhibiting chemotaxis. The recommended initial dose of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg usually induces remission within a 2 wk period, with the most dramatic response occurring in patients with the serosal type[50]. Thereafter, tapering dosage over a 6 to 8 wk period is recommended. Re-evaluation of the EGE diagnosis (and type) must be considered in cases of initial unresponsiveness[51]. Steroid dependent disease reportedly accounts for about 20% of cases[7] and, consequently, low doses of prednisone may be needed to maintain remission. Unfortunately, long-term steroid treatment predisposes some patients to serious side effects; in such cases, steroid-sparing agents can be of benefit.

Budesonide

Budesonide, a common steroid treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, has a high affinity for steroid receptors and produces fewer side effects due to its lower systemic impact. It has also been demonstrated as effective for induction and maintenance of remission in the majority of reported cases (Table 2)[15,26,52-59]. The usual dose is 9 mg/d, which can be tapered to 6 mg/d for use as prolonged maintenance therapy. The better safety profile of budesonide, compared to other steroid drugs, is of particular benefit for management of EGE cases over the long term, especially in the setting of steroid dependent disease.

Table 2.

Published cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis treated with budesonide

| Ref. | Patient no. | Intestinal layer | Location | Previous treatment | Response |

| Russel et al[52], 1994 | 1 | Mucosal | Ileum and cecum | Intolerant to steroids Failure of cromolyn sodium and mesalazine | Efficacy comparable to steroids over 5 mo |

| Tan et al[53], 2001 | 1 | Full thickness with ascites | Antrum | Steroid dependent | Remission (+) over 2 yr |

| Siewert et al[54], 2006 | 1 | Mucosal | Duodenum to ileum | None | Response (+) |

| Lombardi et al[55], 2007 | 1 | Mucosal + submucosal | Ileum | Relapse after stopping budesonide and cromolyn sodium | Remission (+) on budesonide alone over 4 mo |

| Elsing et al[56], 2007 | 1 | Muscular | Jejunum | Surgery + steroids for relapse | Remission (+) over 3 mo |

| Shahzad et al[57], 2011 | 1 | Mucosal | Antrum + colon | None | Response (+) |

| Busoni et al[58], 2011 | 5 | Mucosal | Lower + upper GI tract | Prednisone/methylprednisolone | Remission (+) |

| Lombardi et al[59], 2011 | 1 | Muscular | Pyloric stenosis | Methylprednisolone | Remission (+) over 6 mo |

| Müller et al[26], 2014 | 1 | Mucosal | Duodenum + colon + ileum | None | 50% response (combined with 6-food elimination diet) |

| Wong et al[15], 2015 | 1 | Mucosal +/- serosal or muscular | - | None | Recurrent symptoms |

GI: Gastrointestinal.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine, a common immunosuppressive agent used in organ transplant and patients with autoimmune diseases, is an immunomodulator that induces apoptosis of T and B cells. The efficacy of this steroid-sparing agent has been demonstrated in patients with steroid dependent and refractory EGE disease. The usual dose for EGE patients is similar to that used in patients with IBD (2-2.5 mg/kg)[9,60,61]; lower doses may not be effective[62].

Montelukast sodium

Montelukast sodium, commonly used to treat asthma, is a selective leukotriene (LTD4) inhibitor with demonstrated efficacy for various eosinophilic disorders, including EGE. The majority of reports in the literature concerning its use in EGE (Table 3)[5,9,15,21,26,63-70] have shown significant clinical response in patients, either when the drug is used alone or in combination with steroids for induction and maintenance of remission in steroid dependent or refractory disease. The usual dose is 5-10 mg/d.

Table 3.

Published cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis treated with montelukast

| Ref. | Patient no. | Intestinal layer | Location | Previous treatment | Response |

| Neustrom et al[63], 1999 | 1 | Mucosal | Esophagus + stomach + small intestine | Failure of response to elimination diet, cromolyn sodium, ranitidine and hydroxyzine | Clinical and histologic response (+) |

| Schwartz et al[64], 2001 | 1 | Serosal | Duodenum | Steroid dependent | Remission (+) over 4 wk |

| Lu et al[65], 2003 | 2 | Mucosal | - | Steroid dependent | 1 → Not effective |

| 2 → Partial response with tapering of prednisone to 10 mg/d | |||||

| Vanderhoof et al[66], 2003 | 8 | Mucosal | Esophagus (n = 4) Duodenum (n = 2) Colon (n = 2) | Failure of standard therapies | Clinical response (+) within 1 mo |

| Copeland et al[9], 2004 | 1 | Mucosal | Stomach | Steroid refractory EGE (also receiving 6MP and 5ASA for UC) | Not effective |

| Friesen et al[67], 2004 | 40 | Mucosal | Duodenum | None | Response (+) within 2 wk |

| Quack et al[68], 2005 | 1 | Serosal | Ileum | Steroid dependent | Remission (+) over 2 yr |

| Urek et al[21], 2006 | 1 | Serosal | Ileum | Steroid dependent | Response (+) within 4 wk |

| De Maeyer et al[69], 2011 | 1 | - | - | Steroid dependent | Response (+) |

| Tien et al[5], 2011 | 12 | Mucosal | Stomach + duodenum + colon + esophagus | 4 → None 8 → Steroid dependent | Remission (+) over 12 mo 4/8 → Successful steroid tapering 3/8 → Not effective 1/8 → Lost to follow-up |

| Selva Kumar et al[70], 2011 | 1 | Mucosal | Small intestine | Unresponsive to standard therapy | Response (+) |

| Müller et al[26], 2014 | 2 | Mucosal (+/- serosal or muscular) | Stomach + small intestine | 1 and 2 → Steroid dependent | 1 → Remission (+) in combination with low-dose prednisone 2 → Remission (+) (off steroids) |

| Wong et al[15], 2015 | 2 | Mucosal (+/- serosal or muscular) | - | 1: Steroid dependent 2: None | Remission (+) for 36 mo (in combination with prednisone) Asymptomatic for 10 mo |

5ASA: 5-Aminosalicylic acid; 6MP: 6 Mercaptopurine; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

Oral cromolyn sodium

Oral cromolyn sodium is a mast cell stabilizer that blocks the release of immune mediators and the subsequent activation of eosinophils. While it has been shown to have significant efficacy in many of the reported cases of EGE, its effect was only modest in others, for unknown reasons (Table 4)[4,52,71-77]. The usual dose is 200 mg tid or qid.

Table 4.

Published cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis treated with cromolyn sodium

| Ref. | Patient no. | Intestinal layer | Location | Previous treatment | Response |

| Moots et al[71], 1988 | 1 | Mucosal +/- muscular | Small intestine + colon | Prednisone, cyclophosphamide | Response (+) in 10 wk Maintenance over 2.5 yr |

| Talley et al[4], 1990 | 3 | Mucosal | - | None | 1 → Response (+) 2 → No response |

| Di Gioacchino et al[72], 1990 | 2 | Mucosal | Stomach + duodenum | None | Clinical and histologic response (+) after 4-5 mo |

| Beishuizen et al[73], 1993 | 2 | Mucosal | Upper gastrointestinal tract | Steroids | Prolonged response (+) |

| Van Dellen et al[74], 1994 | 1 | Mucosal | Stomach + duodenum | Elemental diet (poorly tolerated) | Response (+) |

| Russel et al[52], 1994 | 1 | Mucosal | Ileum + colon | Steroid dependent | None (failure to taper steroids) |

| Pérez-Millán et al[75], 1997 | 1 | Serosal | Duodenum | None | Response (+) over 6 mo |

| Suzuki et al[76], 2003 | 1 | Mucosal | Stomach + duodenum | Targeted elimination diet (poorly tolerated) | Response (+) (in combination with ketotifene) |

| Sheikh et al[77], 2009 | 3 | Mucosal Mucosal Mucosal +/- muscular | Esophagus + stomach + duodenum Stomach + duodenum + colon Esophagus + stomach + duodenum + colon | Steroid refractory None Steroid dependent | Not effective Partial response Response (+) with tapering of prednisone over 6 mo |

Ketotifene

Ketotifene is a 2nd-generation H1-antihistamine agent that also modulates the release of mast cell mediators. Melamed et al[78] described 6 patients with EGE who responded clinically and histologically to ketotifen; however, Freeman et al[79] reported a single case in which the drug failed to maintain disease remission. This agent has also been proposed as an adjunct to steroids and montelukast for treating refractory EGE[5]. The usual dose is 1-2 mg twice daily.

Biologic agents

Biologic agents have also been reported in some case studies of EGE. Mepolizumab (anti-IL5) was reported to have improved tissue and peripheral eosinophilia, but without relieving symptoms, in 4 patients with EGE[80]; unfortunately, another report associated its use with rebound hypereosinophilia[81]. Omalizumab (anti-IgE) was reported to similarly result in a significant histologic response[82] but to be unlikely to efficiently treat EGE patients with a serum IgE level > 700 kIU/L[83]. Infliximab (anti-TNF) was reported as highly effective for inducing remission in refractory EGE, but its use is limited by the development of resistance and secondary loss of response, both of which can be managed by switching to adalimumab[84].

Surgery

Surgery is indicated in cases of severe disease that are complicated by perforation, intussusception or intestinal occlusion. It has been reported that about 40% of EGE patients may need surgery during the course of their disease, and about half of those may experience persistent symptoms postoperatively[85].

Other modalities

Other modalities include intravenous immunoglobulin and interferon-alpha, both of which appear to be effective in treating severe refractory and steroid dependent cases[10,65]. Suplatast tosilate, a TH2 cytokine inhibitor, can be beneficial as well[86]. Finally, fecal microbiota transplantation has also been reported to improve diarrhea in a patient with EGE, even before its application in combination with steroids[87].

FOLLOW UP AND TREATMENT END-POINTS

While most reported treatments of EGE aim to achieve clinical remission[48,67], histologic improvement remains the optimal way to assess a patient’s response, even though it does not always correlate with clinical amelioration[79]. Biopsies can be obtained either endoscopically or under ultrasound guidance[27]. Other less invasive parameters may also be useful in monitoring of treatment response, such as reduction in peripheral eosinophilia[5] and improved radiologic aspects[88]. The choice of appropriate follow-up modality should always be individualized.

CONCLUSION

EGE is a chronic GI disease, having protean manifestations that mimic many other GI disorders. Its diagnosis requires a combination of clinical and pathologic criteria that are evaluated upon suspicious laboratory, radiologic and endoscopic findings. According to the disease severity at initial presentation, many therapeutic modalities can be applied, all of which have been reported in single and case series and have shown variable efficacy. A maintenance regimen is often needed, preferably based upon a safe steroid-sparing drug. Further studies are needed to compare the efficacy and safety profiles of the various treatments available as well as to select predictors of relapses, which might guide decision-making for the kind and duration of maintenance therapy.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Neither author has any personal or financial interests related to the publication of this study or its findings.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Lebanon

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

Peer-review started: December 7, 2015

First decision: February 15, 2016

Article in press: August 17, 2016

P- Reviewer: Capasso R, Gupta N, Liu F S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis: Estimates From a National Administrative Database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:36–42. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, Song L, Shah SS, Talley NJ, Bonis PA. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–306. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang JY, Choung RS, Lee RM, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Talley NJ. A shift in the clinical spectrum of eosinophilic gastroenteritis toward the mucosal disease type. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:669–675; quiz e88. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Shorter RG, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a clinicopathological study of patients with disease of the mucosa, muscle layer, and subserosal tissues. Gut. 1990;31:54–58. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tien FM, Wu JF, Jeng YM, Hsu HY, Ni YH, Chang MH, Lin DT, Chen HL. Clinical features and treatment responses of children with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;52:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keshavarzian A, Saverymuttu SH, Tai PC, Thompson M, Barter S, Spry CJ, Chadwick VS. Activated eosinophils in familial eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed C, Woosley JT, Dellon ES. Clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and resource utilization in children and adults with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butterfield JH, Murray JA. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and gluten-sensitive enteropathy in the same patient. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:552–553. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200205000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copeland BH, Aramide OO, Wehbe SA, Fitzgerald SM, Krishnaswamy G. Eosinophilia in a patient with cyclical vomiting: a case report. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciccia F, Giardina AR, Alessi N, Rodolico V, Galia M, Ferrante A, Triolo G. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for steroid-resistant eosinophilic enteritis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:1018–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daneshjoo R, J Talley N. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4:366–372. doi: 10.1007/s11894-002-0006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:11–28; quiz 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe JS, James SP, Mullins GE, Braun-Elwert L, Lubensky I, Metcalfe DD. Evidence for an abnormal profile of interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and gamma-interferon (gamma-IFN) in peripheral blood T cells from patients with allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Clin Immunol. 1994;14:299–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01540983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein NC, Hargrove RL, Sleisenger MH, Jeffries GH. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1970;49:299–319. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong GW, Lim KH, Wan WK, Low SC, Kong SC. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: Clinical profiles and treatment outcomes, a retrospective study of 18 adult patients in a Singapore Tertiary Hospital. Med J Malaysia. 2015;70:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cello JP. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis--a complex disease entity. Am J Med. 1979;67:1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90652-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin WG, Park CH, Lee YS, Kim KO, Yoo KS, Kim JH, Park CK. Eosinophilic enteritis presenting as intussusception in adult. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:13–17. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeshima A, Murakami H, Sadakata H, Saitoh T, Matsushima T, Tamura J, Karasawa M, Naruse T. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis presenting with acute pancreatitis. J Med. 1997;28:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madhotra R, Eloubeidi MA, Cunningham JT, Lewin D, Hoffman B. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis masquerading as ampullary adenoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:240–242. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pineton de Chambrun G, Gonzalez F, Canva JY, Gonzalez S, Houssin L, Desreumaux P, Cortot A, Colombel JF. Natural history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:950–956.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urek MC, Kujundzić M, Banić M, Urek R, Veic TS, Kardum D. Leukotriene receptor antagonists as potential steroid sparing agents in a patient with serosal eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Gut. 2006;55:1363–1364. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chehade M, Sicherer SH, Magid MS, Rosenberg HK, Morotti RA. Multiple exudative ulcers and pseudopolyps in allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis that responded to dietary therapy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:354–357. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31803219d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manatsathit W, Sermsathanasawadi R, Pongpaiboon A, Pongprasobchai S. Mucosal-type eosinophilic gastroenteritis in Thailand: 12-year retrospective study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96 Suppl 2:S194–S202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen MJ, Chu CH, Lin SC, Shih SC, Wang TE. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813–2816. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alnaser S, Aljebreen AM. Endoscopic ultrasound and hisopathologic correlates in eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:91–94. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.32185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller M, Keller K, Stallmann S, Eckardt AJ. Clinicopathologic Findings in Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A German Case Series. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2014;5:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marco-Doménech SF, Gil-Sánchez S, Jornet-Fayos J, Ambit-Capdevila S, Gonzalez-Añón M. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: percutaneous biopsy under ultrasound guidance. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:286–288. doi: 10.1007/s002619900341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anuradha C, Mittal R, Yacob M, Manipadam MT, Kurian S, Eapen A. Eosinophilic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: imaging features. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012;18:183–188. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.4490-11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng X, Cheng J, Pan K, Yang K, Wang H, Wu E. Eosinophilic enteritis: CT features. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:191–195. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KJ, Hahm KB, Kim YS, Kim JH, Cho SW, Jie H, Park CH, Yim H. The usefulness of Tc-99m HMPAO labeled WBC SPECT in eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin Nucl Med. 1997;22:536–541. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199708000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solis-Herruzo JA, de Cuenca B, Muñoz-Yagüe MT. Laparoscopic findings in serosal eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Report of two cases. Endoscopy. 1988;20:152–153. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothenberg ME, Mishra A, Brandt EB, Hogan SP. Gastrointestinal eosinophils. Immunol Rev. 2001;179:139–155. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.790114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torpier G, Colombel JF, Mathieu-Chandelier C, Capron M, Dessaint JP, Cortot A, Paris JC, Capron A. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: ultrastructural evidence for a selective release of eosinophil major basic protein. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;74:404–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurrell JM, Genta RM, Melton SD. Histopathologic diagnosis of eosinophilic conditions in the gastrointestinal tract. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:335–348. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318229bfe2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackburn GL, Bistrian BR, Maini BS, Schlamm HT, Smith MF. Nutritional and metabolic assessment of the hospitalized patient. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1977;1:11–22. doi: 10.1177/014860717700100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carley A. Anemia: when is it not iron deficiency? Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tefferi A. Blood eosinophilia: a new paradigm in disease classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:75–83. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)62962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macari M, Balthazar EJ. CT of bowel wall thickening: significance and pitfalls of interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1105–1116. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.5.1761105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinstein WM, Wiggett SD. The spectrum of endoscopic and histologic findings in eosinophilic gastroenteritis. A video capsule and push enteroscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:A191. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prussin C. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and related eosinophilic disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guajardo JR, Plotnick LM, Fende JM, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders: a world-wide-web based registry. J Pediatr. 2002;141:576–581. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.127663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Beausoleil JL, Shuker M, Liacouras CA. Predictive values for skin prick test and atopy patch test for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:509–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao WH, Wei KL, Po-Yen-Lin CS. A rare case of spontaneous resolution of eosinophilic ascites in a patient with primary eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:354–359. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.106134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkataraman S, Ramakrishna BS, Mathan M, Chacko A, Chandy G, Kurian G, Mathan VI. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis--an Indian experience. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998;17:148–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada Y, Toki F, Yamamoto H, Nishi A, Kato M. Proton pump inhibitor treatment decreased duodenal and esophageal eosinophilia in a case of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Allergol Int. 2015;64 Suppl:S83–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soavi C, Caselli M, Sioulis F, Cassol F, Lanza G, Zuliani G. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis cured with Helicobacter pylori eradication: case report and review of literature. Helicobacter. 2014;19:237–238. doi: 10.1111/hel.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohe M, Hashino S. Successful treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis with clarithromycin. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27:451–454. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2012.27.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucendo AJ, Serrano-Montalbán B, Arias Á, Redondo O, Tenias JM. Efficacy of Dietary Treatment for Inducing Disease Remission in Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:56–64. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan S. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:177–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Duan L, Ding S, Lu J, Jin Z, Cui R, McNutt M, Wang A. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical manifestations and morphological characteristics, a retrospective study of 42 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1074–1080. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.579998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stone KD, Prussin C. Immunomodulatory therapy of eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1858–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russel MG, Zeijen RN, Brummer RJ, de Bruine AP, van Kroonenburgh MJ, Stockbrügger RW. Eosinophilic enterocolitis diagnosed by means of technetium-99m albumin scintigraphy and treated with budesonide (CIR) Gut. 1994;35:1490–1492. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan AC, Kruimel JW, Naber TH. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis treated with non-enteric-coated budesonide tablets. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:425–427. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siewert E, Lammert F, Koppitz P, Schmidt T, Matern S. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with severe protein-losing enteropathy: successful treatment with budesonide. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lombardi C, Salmi A, Savio A, Passalacqua G. Localized eosinophilic ileitis with mastocytosis successfully treated with oral budesonide. Allergy. 2007;62:1343–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elsing C, Placke J, Gross-Weege W. Budesonide for the treatment of obstructive eosinophilic jejunitis. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:187–189. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-927138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shahzad G, Moise D, Lipka S, Rizvon K, Mustacchia PJ. Eosinophilic enterocolitis diagnosed by means of upper endoscopy and colonoscopy with random biopsies treated with budenoside: a case report and review of the literature. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:608901. doi: 10.5402/2011/608901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Busoni VB, Lifschitz C, Christiansen S, G de Davila MT, Orsi M. [Eosinophilic gastroenteropathy: a pediatric series] Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011;109:68–73. doi: 10.1590/S0325-00752011000100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lombardi C, Salmi A, Passalacqua G. An adult case of eosinophilic pyloric stenosis maintained on remission with oral budesonide. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;43:29–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Redondo-Cerezo E, Cabello MJ, González Y, Gómez M, García-Montero M, de Teresa J. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: our recent experience: one-year experience of atypical onset of an uncommon disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1358–1360. doi: 10.1080/003655201317097254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Netzer P, Gschossmann JM, Straumann A, Sendensky A, Weimann R, Schoepfer AM. Corticosteroid-dependent eosinophilic oesophagitis: azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine can induce and maintain long-term remission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:865–869. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32825a6ab4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim YJ, Chung WC, Kim Y, Chung YY, Lee KM, Paik CN, Chin HM, Hyun Choi HJ. A Case of Steroid Dependent Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis Presenting as a Huge Gastric Ulcer. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2012;12:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neustrom MR, Friesen C. Treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis with montelukast. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:506. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwartz DA, Pardi DS, Murray JA. Use of montelukast as steroid-sparing agent for recurrent eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1787–1790. doi: 10.1023/a:1010682310928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu E, Ballas ZK. Immuno-modulation in the treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S262. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vanderhoof JA, Young RJ, Hanner TL, Kettlehut B. Montelukast: use in pediatric patients with eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:293–294. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200302000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friesen CA, Kearns GL, Andre L, Neustrom M, Roberts CC, Abdel-Rahman SM. Clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics of montelukast in dyspeptic children with duodenal eosinophilia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:343–351. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200403000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quack I, Sellin L, Buchner NJ, Theegarten D, Rump LC, Henning BF. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis in a young girl--long term remission under Montelukast. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Maeyer N, Kochuyt AM, Van Moerkercke W, Hiele M, Montelukast as a treatment modality for eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Selva Kumar C, Das RR, Balakrishnan CD, Balagurunathan K, Chaudhuri K. Malabsorption syndrome and leukotriene inhibitor. J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57:135–137. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moots RJ, Prouse P, Gumpel JM. Near fatal eosinophilic gastroenteritis responding to oral sodium chromoglycate. Gut. 1988;29:1282–1285. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.9.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Gioacchino M, Pizzicannella G, Fini N, Falasca F, Antinucci R, Masci S, Mezzetti A, Marzio L, Cuccurullo F. Sodium cromoglycate in the treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Allergy. 1990;45:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1990.tb00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beishuizen A, van Bodegraven AA, Bronsveld W, Sindram JW. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis--a disease with a wide clinical spectrum. Neth J Med. 1993;42:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Dellen RG, Lewis JC. Oral administration of cromolyn in a patient with protein-losing enteropathy, food allergy, and eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:441–444. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61640-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pérez-Millán A, Martín-Lorente JL, López-Morante A, Yuguero L, Sáez-Royuela F. Subserosal eosinophilic gastroenteritis treated efficaciously with sodium cromoglycate. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:342–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1018818003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki J, Kawasaki Y, Nozawa R, Isome M, Suzuki S, Takahashi A, Suzuki H. Oral disodium cromoglycate and ketotifen for a patient with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, food allergy and protein-losing enteropathy. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2003;21:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sheikh RA, Prindiville TP, Pecha RE, Ruebner BH. Unusual presentations of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: case series and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2156–2161. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Melamed I, Feanny SJ, Sherman PM, Roifman CM. Benefit of ketotifen in patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Am J Med. 1991;90:310–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Freeman HJ. Longstanding eosinophilic gastroenteritis of more than 20 years. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:632–634. doi: 10.1155/2009/565293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Prussin C, James SP, Huber MM, Klion AD, Metcalfe DD. Pilot study of anti-IL-5 in eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S275. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim YJ, Prussin C, Martin B, Law MA, Haverty TP, Nutman TB, Klion AD. Rebound eosinophilia after treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome and eosinophilic gastroenteritis with monoclonal anti-IL-5 antibody SCH55700. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1449–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Foroughi S, Foster B, Kim N, Bernardino LB, Scott LM, Hamilton RG, Metcalfe DD, Mannon PJ, Prussin C. Anti-IgE treatment of eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hochhaus G, Brookman L, Fox H, Johnson C, Matthews J, Ren S, Deniz Y. Pharmacodynamics of omalizumab: implications for optimised dosing strategies and clinical efficacy in the treatment of allergic asthma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:491–498. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turner D, Wolters VM, Russell RK, Shakhnovich V, Muise AM, Ledder O, Ngan B, Friesen C. Anti-TNF, infliximab, and adalimumab can be effective in eosinophilic bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:492–497. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182801e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Naylor AR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Scott Med J. 1990;35:163–165. doi: 10.1177/003693309003500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shirai T, Hashimoto D, Suzuki K, Osawa S, Aonahata M, Chida K, Nakamura H. Successful treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis with suplatast tosilate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:924–925. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dai YX, Shi CB, Cui BT, Wang M, Ji GZ, Zhang FM. Fecal microbiota transplantation and prednisone for severe eosinophilic gastroenteritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16368–16371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Buljevac M, Urek MC, Stoos-Veić T. Sonography in diagnosis and follow-up of serosal eosinophilic gastroenteritis treated with corticosteroid. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:43–46. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]