Abstract

AIM

To investigate the differences in family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and clinical outcomes among individuals with Crohn’s disease (CD) residing in China and the United States.

METHODS

We performed a survey-based cross-sectional study of participants with CD recruited from China and the United States. We compared the prevalence of IBD family history and history of ileal involvement, CD-related surgeries and IBD medications in China and the United States, adjusting for potential confounders.

RESULTS

We recruited 49 participants from China and 145 from the United States. The prevalence of family history of IBD was significantly lower in China compared with the United States (China: 4.1%, United States: 39.3%). The three most commonly affected types of relatives were cousin, sibling, and parent in the United States compared with child and sibling in China. Ileal involvement (China: 63.3%, United States: 63.5%) and surgery for CD (China: 51.0%, United States: 49.7%) were nearly equivalent in the two countries.

CONCLUSION

The lower prevalence of familial clustering of IBD in China may suggest that the etiology of CD is less attributed to genetic background or a family-shared environment compared with the United States. Despite the potential difference in etiology, surgery and ileal involvement were similar in the two countries. Examining the changes in family history during the continuing rise in IBD may provide further insight into the etiology of CD.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Family history, Disease outcome, Inflammatory bowel disease, Epidemiology, genetics, Environment, Medication, Surgery

Core tip: Crohn’s disease (CD) diagnoses are increasing in Asia. While family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is recognized as the strongest independent risk factor for CD in western populations, it is unknown if family history plays a role in Asians. This study compares the prevalence of IBD family history, the relationships of affected relatives, and CD-related outcomes such as ileal involvement, surgery, and medication use between China and the United States.

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), featured by chronic inflammation, most frequently affecting the terminal ileum and colon, but can also involve other portions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from mouth to anus[1]. The first mention of CD appeared in the literature in 1932 in a publication by Burrill Crohn reporting on a subacute or chronic necrotizing and cicatrizing inflammatory disease of the terminal ileum affecting mainly young adults in New York city[2]. Incidence rates of CD were first published in 1965, reporting an estimated 1.3 cases per 100000 person-years during 1955 to 1963 in Scotland[3]. Since then, the incidence rate of CD in western countries has shown a significant increasing trend, and the annual incidence rates between 1991 to 2008 were estimated to range from 10.6 to 29.3 per 100000 in North America, Europe, and Australia[4]. In contrast, the CD incidence rate in Asia was first published in 1974, reporting 0.04 cases per 100000 person-years in Singapore during 1965-1970[5]. Similar to western countries, the incidence of CD has increased over time. The estimated annual CD incidence rate (per 100000 person-years) based on population-based longitudinal cohorts in Hong Kong[6], Japan[7], and South Korea[8] has increased from 0.1-0.6 in 1986-1992 to 1.0-1.3 in 1998-2005.

In China, CD was first documented in the literature in 1960s and the incidence is assumed to be increasing based on single hospital-based studies. The current estimated incidence is 0.1 to 1.3 cases per 100000 person-years[9]. The proposed increase in incidence has been attributed to environmental exposures, such as industrialization and urbanization of the society, westernization of lifestyle and dietary habits, because of the parallelism of their occurrence[4,10,11].

The lower incidence of CD may be due in part to differences in genetic risk factors. Polymorphisms of the NOD2/CARD15 gene have been found to account for up to 20% of CD in Caucasian[12] populations[13], but there have not been consistent findings of such association in China[14-17].

Family history is a window to both the genetic background and shared environment. Having a relative with IBD is the strongest known risk factor for developing CD in western countries[18]. However, family history of IBD among Chinese CD patients has not been studied in detail. Thirteen hospital-based studies reported the prevalence of family history of IBD (any affected family member) among Chinese CD patients to be 0% to 4.5%, although the details on the relations of family members are not known[6,19-29]. In contrast, 8% to 25% of CD patients in western countries have a blood relative with IBD[30,31], and 8% to 14.5% of CD patients have a first-degree relative with IBD[18,31].

Clinical characteristics and complication rates differ among Asians with CD. A systematic review of 151 studies suggested Asian CD patients are more likely to be male, with a higher prevalence of ileocolonic involvement and lower surgical rates than Western estimates[29,32].

We hypothesized that there would be differences in family history of IBD and clinical outcomes between CD patients in China and the United States. We targeted three aims to address our hypothesis. The first was to investigate and compare the prevalence of family history of IBD among CD patients in China and the United States. The second was to examine the distribution of relationships of the affected relatives. Third, we aimed to study the difference in prevalence of CD outcomes including ileal involvement, CD-related surgeries and use of medications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Patients were recruited from one source in China and two sources in the United States. In China, patients with CD seen by gastroenterologists at the IBD clinic of the 6th Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU), Guangdong, China, during a clinic visit from May 2014 to December 2015. This hospital is a referral center for IBD patients in the Guangdong area. In the United States, patients were recruited at Johns Hopkins University-affiliated clinics or through the participant recruitment website ResearchMatch (RM). RM is a disease-neutral, institution-neutral, online volunteer recruitment platform designed to match volunteers with researchers[33]. The Johns Hopkins participants were recruited by email, letter, flyer, or during a clinic visit between May 2015 and February 2016. Individuals who indicated that they had IBD on their ResearchMatch profiles were recruited via email from May 2015 to February 2016.

In China, participants were administered a survey by face-to-face interview with a healthcare professional. In the United States participants completed the survey online (bit.ly/IBD-MIMAS). The survey was created and administered using the REDCap[34] project hosted at Johns Hopkins University. The survey included questions about demographics, timing of CD diagnosis, disease location and treatment history, family history of IBD and relationship, age at diagnosis of IBD type of the affected family members (Appendix tables). Participants were included in the analysis only if they completed the family history and disease outcome modules of the survey and were aged 18 years or older at the time of survey completion. Individuals with unknown family history were excluded (1 individual from the United States who was adopted).

IBD family history assessment

Family history of IBD was classified using self-reported information on the survey. Questions were asked regarding knowledge of any family history, details on the number of relatives affected, as well as the relationship to the participant (Appendix Table 2). Any family history of IBD was defined as having one or more blood relatives diagnosed with any type of IBD. For participants who had any family history of IBD, they were further subdivided as having first-degree relative family history if they had at least one parent, sibling or child with IBD.

Crohn’s disease related outcomes assessment

The primary clinical outcome was ileal involvement. History of ileal involvement was determined by self-report (Appendix Table 3). Secondary outcomes included self-reported history of CD-related surgery, and ever use of IBD-related medications including steroids, immunomodulators, and biologics (Appendix Table 4).

Potential confounding factors

Participants self-reported sex, date of birth, date of CD diagnosis, number of siblings, number of children, and smoking status at CD diagnosis (Appendix Tables 1 and 2). Duration of disease was defined as the period of time from the date of clinical diagnosis to the date of survey completion. Smoking status at the time of diagnosis was categorized as current, former, and never smoker. Participants with more family members and longer disease duration are more likely to have a family member with IBD and the family size and duration of disease differed between countries making these factors potential confounders. Similarly, individuals with longer disease duration had greater potential to have ileal disease detected or medication changes.

Statistical analysis

We compared the demographic differences between China and the United States using frequencies for categorical variables and median and range for continuous variables. Frequency distributions were compared using Fisher’s exact tests and medians were compared with Mood’s median tests. We created a figure similar to a pedigree but for the entire population to examine the familial relationships between countries. We used multivariable logistic regression models to compare the prevalence of family history between China and the United States, adjusting for the total number of siblings and children and the duration of disease at the time of survey. We used separate multivariable logistic regression models to compare the difference in the outcomes between countries adjusting for sex, smoking status at CD diagnosis, age at diagnosis older than 40 years vs less, and disease duration. We conducted all the statistical analysis in SAS® 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

RESULTS

Patient demographics

We included 194 individuals with CD, 49 from China and 145 from the United States (Table 1). In the United States, 111 were recruited from the academic center and 34 from ResearchMatch. Similarities between the two countries included a median age of approximately 26 years at diagnosis and a similar median number of siblings and children. Differences between the two countries included those from China were more likely to be male; had a younger age at diagnosis and age at the time of survey completion; and were diagnosed more recently.

Table 1.

Demographics of Crohn’s disease patients in China and the United States recruited 2014-2016

| China (n = 49) | United States (n = 145) | P value | |

| Age at clinical diagnosis (yr) | 26.6 (13.1-46.7) | 25.9 (5.1-73.1) | 0.87 |

| Age at survey completion (yr) | 29.5 (19.2-49.9) | 43.4 (18.3-82.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Duration of disease at time of survey (yr) | 2.2 (0.0-12.7) | 12.4 (0.0-55.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Calendar year of diagnosis | 2013 (2003-2015) | 2003 (1960-2015) | < 0.0001 |

| Before 1969 | 0 | 1.4% | |

| 1970-1979 | 0 | 6.2% | |

| 1980-1989 | 0 | 9.7% | |

| 1990-1999 | 0 | 25.5% | |

| 2000-2009 | 12.2% | 30.3% | |

| 2010-2015 | 87.8% | 26.9% | |

| Female (%) | 42.9% | 58.6% | 0.06 |

| Smoking status at diagnosis (%) | 0.5 | ||

| Current smoker | 12.2% | 16.5%1 | |

| Former smoker | 6.1% (n = 3) | 10.8% | |

| Never smoker | 81.6% | 72.7% | |

| Number of siblings | 2 (0-7) | 2 (0-9) | 0.2 |

| 0 | 8.2% (n = 4) | 6.9% | |

| 1 | 12.2% | 29.7% | |

| 2 | 44.9% | 30.3% | |

| 3 | 12.2% | 18.6% | |

| 4+ | 22.5% | 14.5% | |

| Number of children | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-7) | 0.81 |

| 0 | 53.1% | 51.0% | |

| 1 | 26.5% | 15.9% | |

| 2 | 18.4% | 22.8% | |

| 3 | 2.0% (n = 1) | 9.0% | |

| 4+ | 0 | 1.3% |

Six participants recruited in the United States did not report smoking status at diagnosis.

Family history of IBD

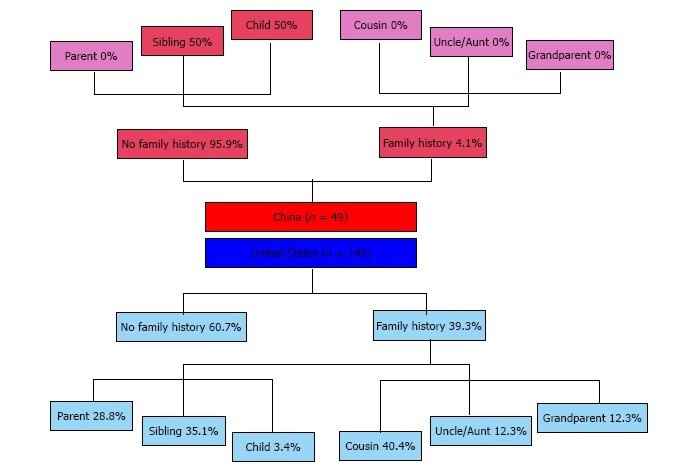

After adjusting for duration of disease at the time of survey and the total number of relatives, the difference in family history was statistically significant. The prevalence of any family history of IBD was markedly lower in China than the United States (China: 4.1% vs United States: 39.3%, adjusted P = 0.0008, Table 2). Family history of IBD in first-degree relatives was also less prevalent in China than in the United States (China: 4.1% vs United States: 23.5%, adjusted P = 0.01). Only two participants in China had a family history of IBD. Both had a first-degree relative affected (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Prevalence and odds ratio of having family history of inflammatory bowel disease in China vs the United States

| China (n = 49) | United States (n = 145) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) P value (Reference = US) | Adjusted1 OR (95% CI) P value (Reference = US) | |

| Any family history of IBD (%) | 4.1% (n = 2) | 39.3% | 0.07 (0.02-0.28) | 0.08 (0.02-0.34) |

| P = 0.0002 | P = 0.0008 | |||

| First-degree family history of IBD (%) | 4.1% (n = 2) | 23.5% | 0.14 (0.03-0.60) | 0.14 (0.03-0.65) |

| P = 0.008 | P = 0.01 |

Adjusted for the total number of siblings and children, and duration of disease at survey completion. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; OR: Odds ratio.

Figure 1.

Relationship map of relatives with inflammatory bowel disease to patients with Crohn’s disease in China and the United States.

For participants who reported any family history of IBD, the distribution of relationships of affected relatives was significantly different (Figure 1). For the two patients who had family history of IBD in China, one had a sibling affected and the other a child. In the United States, the mean number of affected relatives was 1.6 (median 1, maximum 5). The most commonly affected types of relatives were cousin (41.1%), sibling (37.5%), and parent (28.6%).

Disease outcomes

Participants from the two countries had equally high prevalence of ileal involvement (China: 63.3% vs United States: 63.5%, adjusted P = 0.74) and surgery (China: 51.0% vs United States: 49.7%, adjusted P = 0.19; Table 3). Compared with the United States, the percentage of participants that had ever used steroids or a biologic was significantly lower in China. The difference in the use of immunomodulators was of borderline statistical significance with China having greater use than the United States (China: 73.5%, United States: 61.4%, adjusted P = 0.08).

Table 3.

Prevalence and odds ratio of Crohn’s disease outcomes in China vs the United States

| Outcome | China (n = 49) | United States (n = 145) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI), P value (Reference = US) | Adjusted1 OR (95%CI), P value (Reference = US) |

| Ileal involvement | 63.3% | 63.5% | 0.99 (0.50-1.94) | 1.14 (0.51-2.55) |

| P = 0.98 | P = 0.74 | |||

| Surgery for IBD | 51.0% | 49.7% | 1.06 (0.55-2.02) | 1.70 (0.77-3.75) |

| P = 0.87 | P = 0.19 | |||

| Ever steroids use | 46.9% | 91.0% | 0.09 (0.04-0.19) | 0.19 (0.07-0.50) |

| P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0007 | |||

| Steroids use within 3 mo of diagnosis | 24.5% | 46.2% | 0.38 (0.18-0.78) | 0.53 (0.22-1.25) |

| P = 0.009 | P = 0.15 | |||

| Ever immunomodulators2 | 73.5% | 61.4% | 1.74 (0.85-3.57) | 2.13 (0.92-4.91) |

| (n = 36) | (n = 89) | P = 0.13 | P = 0.08 | |

| 6-MP/Azathioprine | 88.9% | 89.9% | ||

| Methotrexate | 19.4% | 23.6% | ||

| Cyclosporine | 0% | 6.7% | ||

| Tacrolimus | 0% | 3.4% | ||

| Ever biologics use | 34.7% | 73.8% | 0.19 (0.09-0.38) | 0.09 (0.04-0.24) |

| P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | |||

| Ever TPN use | 8.2% | 21.4% | 0.33 (0.11-0.98) | 0.67 (0.19-2.38) |

| P = 0.05 | P = 0.54 | |||

| Antibiotics use within 30 d before time of survey | 18.8% | 15.9% | 1.22 (0.52-2.87) | 1.29 (0.47-3.55) |

| P = 0.64 | P = 0.62 |

Adjusted for sex, smoking status at diagnosis, age at diagnosis older than 40 years or less, and duration of disease at survey completion;

For ever users of immunomodulators, the percentage of use of each type of immunomodulators was calculated. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; 6-MP: Mercaptopurine; TPN: Total parenteral nutrition; OR: Odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of family history of IBD and CD related clinical outcomes were different in China and the United States. The probability that CD patients from China had any blood relative affected with IBD was only 1/10 that of the United States CD patients, despite both patient populations coming from academic medical centers with dedicated IBD clinics. The percentage of CD patients in China who had first-degree relative affected with IBD was 1/6 that of the United States. Despite the differences in family history, the two countries shared high prevalence of ileal involvement and surgical history for IBD. However, CD patients in China were less likely to have ever used steroids and biologics but more likely to use immunomodulators, which might reflect differences in access to medications or practice variation.

Both the Chinese and the US estimates of family history prevalence are high compared with other studies. One possible reason is that the recruitment sites have dedicated IBD clinics with large numbers of patients referred by outside providers often because of greater disease severity, which might be associated with genetic predisposition. The higher estimates could also be due to the difference in ascertainment methods of family history. We ascertained family history through self-report on a questionnaire instead of obtaining information from physicians’ notes in medical records. We believe that self-report might be able to capture more accurate information on detailed family history than medical records.

There has been much interest in investigating the characteristics of CD in Asian and western countries, but CD patients in China and the US have rarely been compared. Luo et al[29] compared family history of 85 Chinese and 68 American patients based on information obtained from medical records. They concluded Chinese CD patients had lower prevalence of CD family history than Americans (China 1% vs United States 12%, P = 0.016). One strength of our study was that we used the same questionnaire in both settings (available in English and Mandarin after back-translation confirmation) to ascertain family history during the same time period. In the comparison of family history prevalence, we adjusted for confounders such as patient’s disease duration and family size.

We analyzed the distribution of relationships of affected relatives, which was rarely reported in previous studies in China. Although no individuals from China reported a cousin with IBD, this was the most commonly affected relative type in the United States. This finding could point to shared environmental risk between cousins and cases that could be explored further, especially among the Chinese CD participants as diagnoses of IBD are expected to increase in the coming years.

More than half of CD patients in both China and the United States had history of ileal involvement and about half had undergone surgeries to treat CD. This implies that CD patients of the two countries had similar severity of disease despite differences in family history and duration of disease. In contrast, Luo et al[29] found Chinese CD patients had significantly lower odds of having ileocaecum involvement compared with Americans. We were not able to examine the association of IBD family history and CD outcome by country in the present study, because the small number of individuals with IBD family history in China (n = 2) limited this analysis.

CD patients in China were less likely to have used steroids or biologics than those in the United States. Prideaux et al[23] had a similar finding when comparing steroid use at diagnosis and ever use of biologics between CD patients in Melbourne vs those in Hong Kong (steroids: Hong Kong 37.0% vs Melbourne 61.2%, P < 0.001; anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Hong Kong 11.0% vs Melbourne 39.9%, P < 0.001). This could be due to either real difference in the needs for steroids treatment or difference in physicians’ practicing patterns. These same reasons could explain the differences in biologic use with the additional facts that biologics were introduced into China market later than the United States (2007 vs 1999), that only infliximab is currently available, and that most Chinese patients pay out of pocket at the United States equivalent rates limiting the population that has access to these drugs.

In conclusion, the lower prevalence of familial clustering of IBD among CD patients in China may suggest that the etiology of CD in Chinese population is to a lesser extent attributed to genetic background or family-shared environment compared with the US population. Despite the potential difference in etiology, CD patients from China were as likely to have a history of ileal involvement or have a history of surgery for IBD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Ludwig-Bayless Science Award for overall support of the study. We also acknowledge ResearchMatch.org. Part of the recruitment for the study included was done via ResearchMatch, a national health volunteer registry that was created by several academic institutions and supported by the United States National Institutes of Health as part of the Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) program. ResearchMatch has a large population of volunteers who have consented to be contacted by researchers about health studies for which they may be eligible.

COMMENTS

Background

Family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the strongest risk factor for developing Crohn’s disease (CD) among Western population, and it is also potentially associated with higher probability of having ileal involvement and demand for surgical treatment for CD. However, the prevalence of IBD family history and its role in CD among Asian population has not been well studied.

Research frontiers

CD has a complex and multifactorial etiology. The roles of and interactions among genetic background, gut microbiota, diet, and autoimmunity are at the frontiers of research. Although the incidence rate of CD in Asian countries is relatively low compared with Western countries, CD incidence is increasing. This epidemiological change gives us a unique opportunity to explore the driving factors of the disease, which could increase the authors understanding of CD and ultimately lead to novel therapeutics.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Few studies compare family history and disease outcomes of Western and Asian CD patients. The few available studies are mostly based on chart review of patients’ medical records from different countries and in different settings, which may be biased by the level of detail recorded within the different medical systems. The current study is innovative in that CD patients from China and United States were investigated with the same survey during the same time period Patients reported information on family history and smoking history themselves, rather than relying on medical notes.

Applications

The results of this study suggest lower prevalence of IBD familial clustering among CD patients in China as compared with the United States. This may suggest that the etiology of CD in Chinese population is to a lesser extent attributed to genetic background or family-shared environment compared with the United States population. Despite the potential difference in etiology, CD patients from China were just as likely to have a history of ileal involvement or have a history of IBD-related surgery as those from United States.

Terminology

CD is a form of IBD, featured by chronic inflammation, most frequently affecting the terminal ileum and colon, but can also involve other portions of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus.

Peer-review

In the presented study the differences in family history and clinical outcomes among individuals residing in China and the United States were investigated with a survey-based cross-sectional study. The prevalence of IBD family history was significantly lower in China. It will be interesting to see if the results change as the Chinese study population is studied for a longer period of time, including both longer follow-up of the Chinese population and a larger sample size.

Footnotes

Supported by (in part) Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, No. UL1TR001079.

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Institutional Review Boards at the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.

Informed consent statement: All study participants provided consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: United States

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: June 12, 2016

First decision: July 20, 2016

Article in press: September 15, 2016

P- Reviewer: Ozen H, Vradelis S S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. 1932. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle J, Blair DW. Epidemiology of regional enteritis in North-East Scotland. Br J Surg. 1965;52:215–217. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800520318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54.e42; quiz e30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SK. Crohn’s disease in Singapore. Med J Aust. 1974;1:266–269. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1974.tb93145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leong RW, Lau JY, Sung JJ. The epidemiology and phenotype of Crohn’s disease in the Chinese population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:646–651. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita N, Toki S, Hirohashi T, Minoda T, Ogawa K, Kono S, Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y, Sawada T, Muto T. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Japan: nationwide epidemiological survey during the year 1991. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30 Suppl 8:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, Park JY, Kim HY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim JS, Song IS, Park JB, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542–549. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye L, Cao Q, Cheng J. Review of inflammatory bowel disease in China. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:296470. doi: 10.1155/2013/296470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng SC, Bernstein CN, Vatn MH, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV, Tysk C, O’Morain C, Moum B, Colombel JF. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:630–649. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molodecky NA, Kaplan GG. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2010;6:339–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cézard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O’Morain CA, Gassull M, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo QS, Xia B, Jiang Y, Qu Y, Li J. NOD2 3020insC frameshift mutation is not associated with inflammatory bowel disease in Chinese patients of Han nationality. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1069–1071. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i7.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lv C, Yang X, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Chen Z, Long J, Zhang Y, Zhong C, Zhi J, Yao G, et al. Confirmation of three inflammatory bowel disease susceptibility loci in a Chinese cohort. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1465–1472. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang ZW, Ji F, Teng WJ, Yuan XG, Ye XM. Risk factors and gene polymorphisms of inflammatory bowel disease in population of Zhejiang, China. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:118–122. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Gao X, Guo CC, Wu KC, Zhang X, Hu PJ. OCTN and CARD15 gene polymorphism in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4923–4927. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peeters M, Nevens H, Baert F, Hiele M, de Meyer AM, Vlietinck R, Rutgeerts P. Familial aggregation in Crohn’s disease: increased age-adjusted risk and concordance in clinical characteristics. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:597–603. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Ren J, Wang G, Gu G, Wu X, Ren H, Hong Z, Hu D, Wu Q, Li G, et al. Diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease is associated with increased rate of abdominal surgery: A retrospective study in Chinese patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang XQ, Zhang Y, Xu CD, Jiang LR, Huang Y, Du HM, Wang XJ. Inflammatory bowel disease in Chinese children: a multicenter analysis over a decade from Shanghai. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:423–428. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318286f9f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi F, Chen M, Huang M, Li J, Zhao J, Li L, Xia B. The trend in newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease and extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease in central China: a retrospective study of a single center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1424–1429. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283583e5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Zhu W, Zuo L, Zhang W, Gong J, Gu L, Cao L, Li N, Li J. Frequency and risk factors of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease after intestinal resection in the Chinese population. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1539–1547. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1902-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz P, Williams J, Bell SJ, Connell WR, Brown SJ, Lust M, Desmond PV, Chan H, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and management of inflammatory bowel disease in Hong Kong versus Melbourne. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:919–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song XM, Gao X, Li MZ, Chen ZH, Chen SC, Hu PJ, He YL, Zhan WH, Chen MH. Clinical features and risk factors for primary surgery in 205 patients with Crohn’s disease: analysis of a South China cohort. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1147–1154. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318222ddc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow DK, Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Wong VW, Wu JC, Leong RW, Chan FK. Predictors of corticosteroid-dependent and corticosteroid-refractory inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of a Chinese cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:843–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow DK, Sung JJ, Wu JC, Tsoi KK, Leong RW, Chan FK. Upper gastrointestinal tract phenotype of Crohn’s disease is associated with early surgery and further hospitalization. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:551–557. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leong RW, Lawrance IC, Chow DK, To KF, Lau JY, Wu J, Leung WK, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Association of intestinal granulomas with smoking, phenotype, and serology in Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1024–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leong RW, Armuzzi A, Ahmad T, Wong ML, Tse P, Jewell DP, Sung JJ. NOD2/CARD15 gene polymorphisms and Crohn’s disease in the Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1465–1470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo CH, Wexner SD, Liu QS, Li L, Weiss E, Zhao RH. The differences between American and Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:166–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth MP, Petersen GM, McElree C, Vadheim CM, Panish JF, Rotter JI. Familial empiric risk estimates of inflammatory bowel disease in Ashkenazi Jews. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1016–1020. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weterman IT, Peña AS. Familial incidence of Crohn’s disease in The Netherlands and a review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:449–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thia KT, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Yang SK. An update on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3167–3182. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, Scott KW, Lebo L, Hassan N, Lightner C, Pulley J. ResearchMatch: a national registry to recruit volunteers for clinical research. Acad Med. 2012;87:66–73. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ab7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]