Abstract

The diversity and ecological function of microorganisms associated with Euphausia superba, still remain unknown. This study identified 75 microbial isolates from E. superba, that is 42 fungi and 33 bacteria including eight actinobacteria. And all the isolates showed NaF tolerance in conformity with the nature of the fluoride krill. The maximum concentration was 10%, 3% and 0.5% NaF for actinobacteria, bacteria and fungi, respectively. The results demonstrated that 82.4% bacteria, 81.3% actinobacteria and 12.3% fungi produced antibacterial metabolites against pathogenic bacteria without NaF; the MIC value reached to 3.9 μg/mL. In addition, more than 60% fungi produced cytotoxic metabolites against A549, MCF-7 or K562 cell lines. The presence of NaF led to a reduction in the producing antimicrobial compounds, but stimulated the production of cytotoxic compounds. Furthermore, seven cytotoxic compounds were identified from the metabolites of Penicillium citrinum OUCMDZ4136 under 0.5% NaF, with the IC50 values of 3.6–13.1 μM for MCF-7, 2.2–19.8 μM for A549 and 5.4–15.4 μM for K562, respectively. These results indicated that the krill microbes exert their chemical defense by producing cytotoxic compounds to the mammalians and antibacterial compounds to inhibiting the pathogenic bacteria.

Diverse microorganisms have been acting in a state of commensalism or parasitism with animals and plants for thousands of years1. Mutualistic relationships are abundant in the nutrient cycle, and enforce the protection between microorganisms and the host against environmental conditions2. The Antarctic region is considered a unique and severe ecological environment, dominated by microorganisms3. The Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is the staple food source for whales, fishes and seals, playing a vital role in the Antarctic Ocean ecosystem4. Previous research on Antarctic krill has focused on the distribution, the fishing demand and conservation measures5. Consequently, few studies have investigated the molecular biology and chemistry of the mutualism relationship between Antarctic krill and its associate microbes. Bacteria growth occurs on the surface and stomach of krill, and is an important component of the total digestive process in E. superba6,7. A psychrotrophic halotolerant, Psychrobacter proteolyticus sp. 116, was isolated and identified from the stomach of the Antarctic krill8. However, there are no reports on phylogenetic and bioactive microorganisms from E. superba. Additionally, the function of the microorganisms to E. superba has yet to be investigated. Thus, we investigated the diversity of microbial community, the analysis of phylogenetic relationships and the chemical defenses provided to their host of microorganisms associated with E. superba collected in the Antarctic area FAO48.1. The chemical defenses of the microbes from E. superba to their host were represented as the inhibitions on aquatic and human pathogenic bacteria as well as the cytotoxicity to mammal cells.

In addition, the impacts of the abnormally high levels of fluoride contents in E. superba, due to E. superba concentrating fluoride from the seawater, was investigated9. Although high concentrations of fluoride are toxic to other animals, it is an important component of krill cuticle formation10. The fluoride content varies in different part of E. superba; the fresh shell has levels approximately five times higher (13000 μg/g) than the meat11. The biological availability of fluoride in E. superba allows the utilization of sodium fluoride (NaF)12. Thus, commensalism was also studied by investigating the tolerance of the microbial community to NaF.

Results

Phylogenetic Diversity of Culturable strains Associated with Euphausia superba

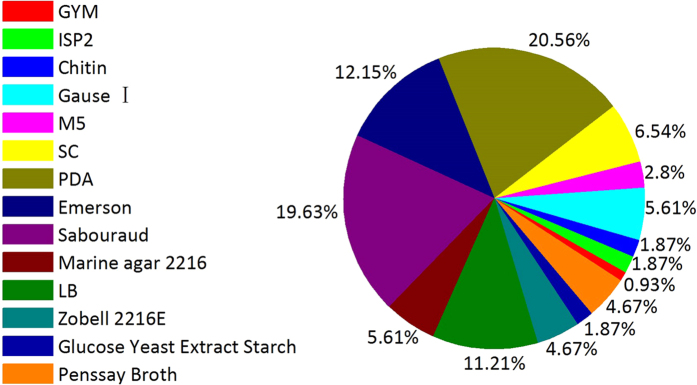

Using thirteen culture media (Table 1), 134 microbial isolates were obtained from E. superba. The duplicated strains were removed using a detailed morphological approach, pigment formation and HPLC fingerprint analysis of the extracts. The 75 representative isolates, including 42 fungal strains, 33 bacterial strains among which eight strains belonged to actinobacteria, were selected for sequencing and identified successfully (Table 2). Using gene sequences and phylogenetic analysis, these 75 representative strains were classified into eleven genera, nine families, and seven orders within seven classes of four phyla; most sequence showed from 98% to 100% homology (Table 2, Figs S1–S75). The most suitable medium for isolating fungi, actinobacteria and bacteria from E. superba was PDA, M5 and LB medium, respectively (Fig. 1). The optimum temperature for isolating bacteria, actinobacteria and fungi was 16 °C, 16 °C and 28 °C, respectively. Among 25 bacterial isolates, 23 bacterial isolates were obtained at 16 °C and only two isolates, Streptomyces sp. OUCMDZ4220 and Advenella sp. OUCMDZ4222, were obtained at 4 °C. Eight actinobacterial isolates were obtained at 16 °C, while 42 fungal isolates were obtained at 28 °C.

Table 1. Ingredient of media used for isolation and fermentation of microbial strains from E. superbaa.

| Microbes | Medium | Ingredient (L−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | GYM | 4.0 g dextrose,4.0 g yeast extract,10.0 g malt extract,2.0 g CaCO3,12.0 g agar |

| ISP2 | 4.0 g yeast extract,10.0 g malt extract,4.0 g dextrose,20.0 g agar | |

| Chitin | 2.0 g chitin, 1.0 g NH4Cl, 0.9 g K2HPO4·3H2O, 0. g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O 0.001 g FeSO4, 0.001 g ZnSO4, 0.1 g CaF2, 20.0 g agar | |

| M5 | 20.0 g agar | |

| SC | 10.0 g soluble starch, 0.3 g casein, 2.0 g KNO3, 2.0 g NaCl, 2.0 g K2HPO4, 0.05 g MgSO4·7H2O, CaCO3 0.02 g, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 20.0 g agar | |

| Actinobacterial medium 2#b | 20.0 g glucose, 10.0 g soluble starch, 10.0 g peptone, 10 g yeast extract, 3.0 g beef extract, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4, 2.0 g CaCO3, pH 7.5–8.0. | |

| Fungi | PDA | 200 g potato extract, 20 g dextrose, 20.0 g agar |

| Emerson | 1.0 g dextrose,1.0 g yeast extract powder,4.0 g peptone,2.5 g NaCl,18.0 g agar | |

| Sabouraud | 10.0 g peptone, 40.0 g maltose, 20.0 g agar | |

| Fungal medium 2#b | 20.0 g maltose,10.0 g aginomoto,0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.3 g MgSO4·7H2O,10.0 g dextrose, 3.0 gyeast extract, 1.0 g corn steep liquor,20.0 g mannitol, pH6.5 | |

| SWSb | 1.0 g peptone, 10.0 g soluble starch, pH 7.5–8.0 | |

| Bacteria | Marine agar 2216c | 5.0 g peptone, 1.0 g yeast extract, 0.1 g ferric citrate, 0.08 g KBr, 19.45 g NaCl, 8.8 g MgCl2, 3.24 g Na2SO4, 1.8 g CaCl2, 0.55 g KCl, 0.16 g NaHCO3, 0.0016 g, NH4NO3, 0.008 g Na2HPO4, 0.022 g H3BO3, 20.0 g agar |

| Luria Bertani (LB)b,c | 5.0 g yeast extract, 10.0 g peptone, 5.0 g NaCl, 15.0 g agar | |

| Zobell 2216E | 5.0 g peptone,3.0 g yeast extract,15.0–20.0 g agar | |

| Glucose Yeast Extract Starch | 10.0 g dextrose, 10.0 g yeast extract,10.0 g starch, 5.0 g NaCl, 3.0 g CaCO3, 20.0 gagar, pH 7.0 | |

| Penssay Broth | 1.5 g beef extract, 1.5 g yeast extract, 5.0 g tryptone, 3.5 g NaCl, 1.0 g dextrose, 4.8 g K2HPO4·3H2O, pH 7.2 |

aAll media were prepared with natural sterile seawater and adjusted corresponding pH prior to autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min.

bThe liquid media were used to ferment actinobacteria, bacteria and fungi in bioassay and compound isolation, respectively.

cThe 2216E and LB media were also used to culture aquatic and human pathogenic bacteria in the antibacterial tests, respectively.

Table 2. Phylogenetic affiliations of culturable isolates from E. superba.

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Strain No. | Genebank accession No. | Top Blast match No. | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | Eurotiomycetes | Eurotiales | Trichocomaceae | Penicillium | OUCMDZ4115 | KU216704 | AM745115.1 | 99% |

| OUCMDZ4116 | KU216705 | NR111815.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4117 | KU216706 | NR121224.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4118 | KU216707 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4121 | KU216709 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4122 | KU216710 | KP942910.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4124 | KU216712 | NR121224.1 | 98% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4126 | KU216714 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4127 | KU216715 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4129 | KU216716 | KU613360.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4130 | KU216717 | KR706304.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4132 | KU216719 | KM250379.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4133 | KU216720 | AF033422.1 | 98% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4134 | KU216721 | NR121224.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4136 | KU216722 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4137 | KU216723 | KF973341.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4139 | KU216724 | NR111673.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4140 | KU216725 | NR111815.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4141 | KU216726 | NR111673.1 | 98% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4143 | KU216727 | NR121224.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4145 | KU216728 | NR121224.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4149 | KU216729 | KF973341.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4150 | KU216730 | NR121224.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4151 | KU216731 | NR077145.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4152 | KU216732 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4154 | KU216733 | AY373902.1 | 97% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4156 | KU216735 | AF033422.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4161 | KU216736 | AF033422.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4162 | KU579276 | HQ026745.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4163 | KU216737 | AY373902.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4164 | KU216738 | KJ173539.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4166 | KU216739 | AY373902.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4167 | KU216740 | NR111815.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4168 | KU216741 | NR121224.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4169 | KU216742 | NR111815.1 | 98% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4170 | KU216743 | NR077145.1 | 100% | |||||

| Talaromyces | OUCMDZ4125 | KU216713 | KF984795.1 | 100% | ||||

| Aspergillus | OUCMDZ4120 | KU216708 | NR111041.1 | 99% | ||||

| OUCMDZ4131 | KU216718 | EU821315.1 | 98% | |||||

| Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | Mycosphaerellaceae | Cladosporium | OUCMDZ4138 | KU579275 | GU595035.1 | 99% | |

| OUCMDZ4155 | KU216734 | KJ596569.1 | 99% | |||||

| Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | Debaryomycetaceae | Meyerozyma | OUCMDZ4123 | KU216711 | KF619545.1 | 98% | |

| Firmicutes | Bacilli | Bacillales | Bacillaceae | Bacillus | OUCMDZ4186 | KU291364 | NR117946.1 | 99% |

| OUCMDZ4181 | KU579260 | NR112636.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4190 | KU291366 | KF811045.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4191 | KU291367 | KJ149809.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4192 | KU291368 | FN597644.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4205 | KU579266 | NR116022.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4206 | KU291370 | KF954553.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4207 | KU579267 | KR045745.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4208 | KU291371 | NR113945.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4210 | KU291372 | NR041794.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4211 | KU579268 | KT719214.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4213 | KU291373 | KJ149809.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4215 | KU579270 | NR041455.1 | 99% | |||||

| Staphylococcaceae | Staphylococcus | OUCMDZ4185 | KU579262 | NR113349.1 | 99% | |||

| Planococcaceae | Planococcus | OUCMDZ4188 | KU291365 | NR113814.1 | 99% | |||

| Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Pseudomonadales | Moraxellaceae | Psychrobacter | OUCMDZ4187 | KU579263 | KJ475192.1 | 99% |

| OUCMDZ4189 | KU579264 | NR041455.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4199 | KU291369 | NR027225.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4202 | KU579265 | HM584295.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4212 | KU579269 | NR027225.1 | 100% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4214 | KU291374 | NR028918.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4218 | KU579271 | NR043057.1 | 98% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4219 | KU579272 | NR028948.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4221 | KU579274 | NR028948.1 | 99% | |||||

| Betaproteobacteria | Burkholderiales | Alcaligenaceae | Advenella | OUCMDZ4222 | KU291375 | KF844056.1 | 100% | |

| Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Streptomycineae | Streptomycetaceae | Streptomyces | OUCMDZ4173 | KU291358 | KU317912.1 | 99% |

| OUCMDZ4174 | KU291359 | KM513543.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4176 | KU291360 | KP718508.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4177 | KU291361 | NR115669.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4179 | KU291362 | EU790486.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4182 | KU579261 | NR 041146.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4183 | KU291363 | NR041173.1 | 99% | |||||

| OUCMDZ4220 | KU579273 | NR041173.1 | 100% |

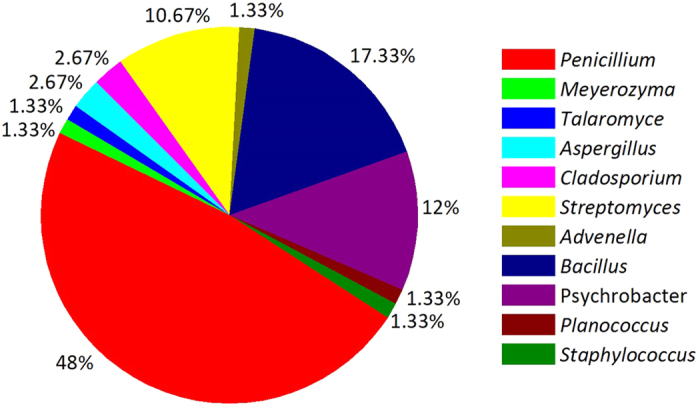

Figure 1. Percentage of microbial isolates associated with E. superba from the different media.

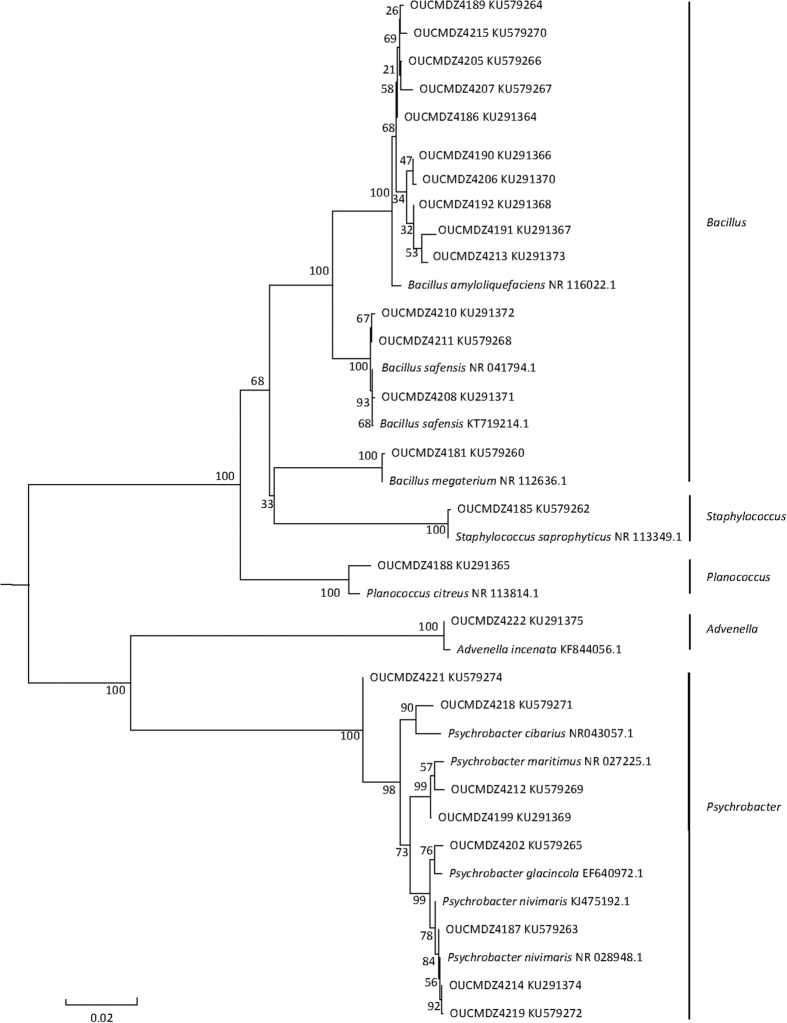

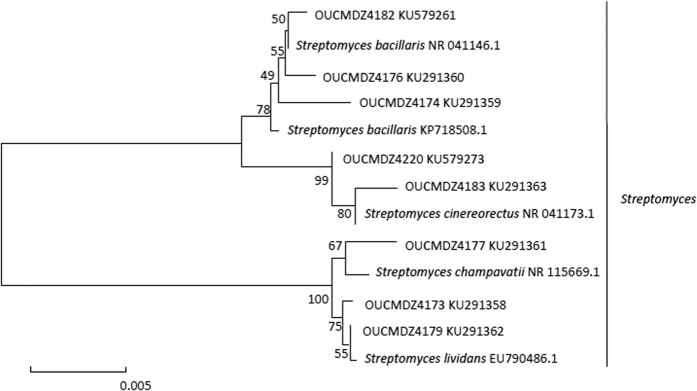

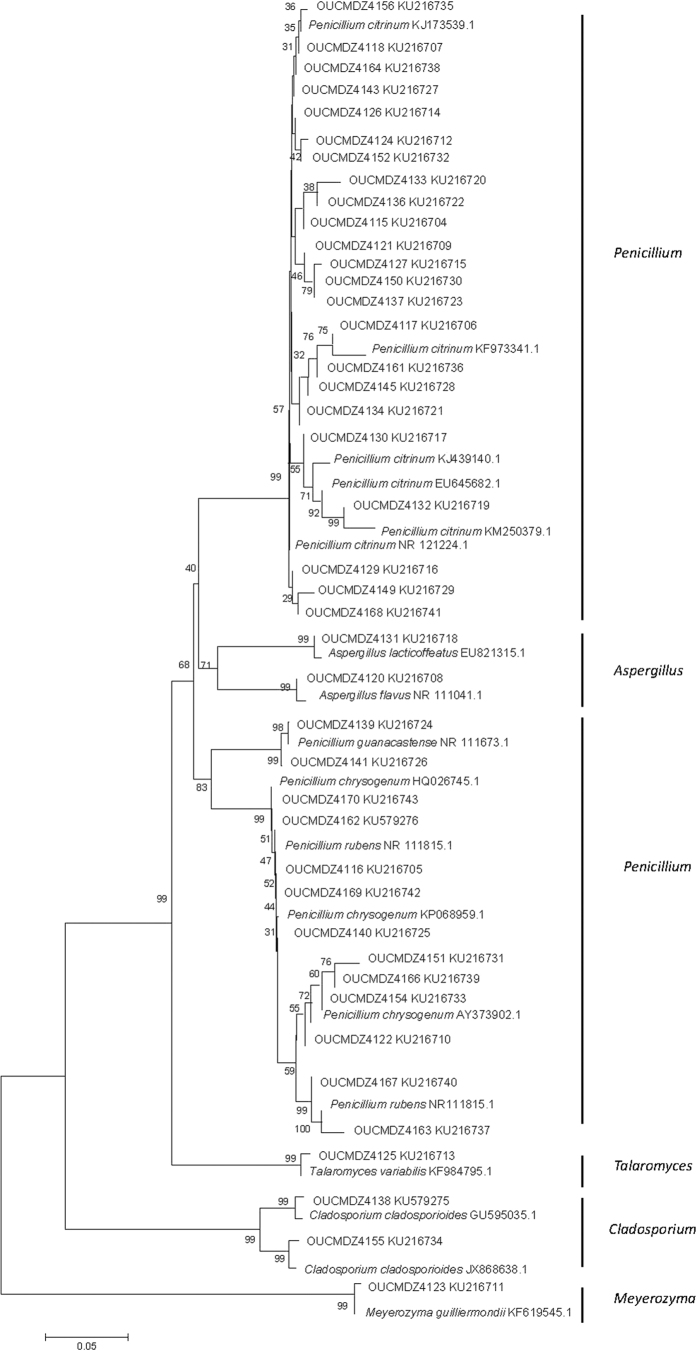

Genebank accession number and their blast results in the NCBI database of the identified strains were summarized (Tables 2 and 3). Based on the homology of 16S or 18S rRNA gene, three phylogenetic trees containing all the isolates were constructed to analyze the phylogenetic relationship of microorganisms (Figs 2, 3 and 4). The taxonomical group classification concluded 42 fungal strains, eight actinobacteria and 25 bacterial strains. The fungal isolates belonged to the phylum Ascomycota, including three classes (Eurotiomycetes, Dothideomycetes and Saccharomycetes), three orders (Eurotiales, Capnodiales and Saccharomycetales), three families (Trichocomaceae, Mycosphaerellaceae and Debaryomycetaceae) and five genera (Penicillium, Cladosporium, Aspergillus, Talaromyces and Meyerozyma) (Fig. 5). Penicillium was the dominant fungal group accounting for 85.7% of all isolates. The bacterial isolates included two phyla, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria. Fifteen isolates belonged to the phylum Firmicutes, including one class (Bacilli), one order (Bacillales), three families (Bacillaceae, Staphylococcaceae and Planococcaceae) and three genera (Bacillus, Staphylococcus and Planococcus); Bacillus was the major bacterial genera identified (Fig. 5). Ten pure cultures belonged to the Proteobacteria phylum including two classes (Gammaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria), two orders (Pseudomonadales and Burkholderiales), two families (Moraxellaceae and Alcaligenaceae) and two genera (Psychrobacter and Advenella). Actinobacteria community associated with E. superba composed of eight isolates belonging to one Actinobacteria phylum, one Actinobacteria class, one Streptomycineae order, one Streptomycetaceae family and one Streptomyces genus (Fig. 5). Streptomyces was the only isolated genus from E. superba. It should be noted that strains OUCMDZ4221 and OUCMDZ4222 were identified as actinobacteria initially because of their morphological features; however, the 16S rRNA gene sequences analysis indicated they belong to Psychrobacter and Advenella, respectively.

Table 3. The classification of culturable isolates from E. superba.

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Quantity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | Eurotiomycetes | Eurotiales | Trichocomaceae | Penicillium | 36 | |

| Talaromyces | 1 | |||||

| Aspergillus | 2 | |||||

| Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | Mycosphaerellaceae | Cladosporium | 2 | ||

| Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | Debaryomycetaceae | Meyerozyma | 1 | ||

| Firmicutes | Bacilli | Bacillales | Bacillaceae | Bacillus | 13 | |

| Staphylococcus | 1 | |||||

| Planococcus | 1 | |||||

| Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Pseudomonadales | Moraxellaceae | Psychrobacter | 9 | |

| Betaproteobacteria | Burkholderiales | Alcaligenaceae | Advenella | 1 | ||

| Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Streptomycineae | Streptomycetaceae | Streptomyces | 8 | |

| Total | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 75 |

Figure 2. Neighbor-joining of phylogenetic tree of 25 representative bacteria isolates from E. superba based on 16S rRNA gene sequences.

The numbers on each node represent the bootstrap value from 1000 replicates and the scale bar represents 0.02 substitutions per nucleotide.

Figure 3. Neighbor-joining of phylogenetic tree of eight representative actinobacterial isolates from E. superba based on 16S rRNA gene sequences.

The numbers on each node represent the bootstrap value from 1000 replicates and the scale bar represents 0.005 substitutions per nucleotide.

Figure 4. Neighbor-joining of phylogenetic tree of 42 representative fungi isolates from E. superba. based on 18S rRNA gene sequences.

The numbers on each node represent the bootstrap value from 1000 replicates and the scale bar represents 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide

Figure 5. Diversity of microbial isolates from E. superba.

The antibacterial activity

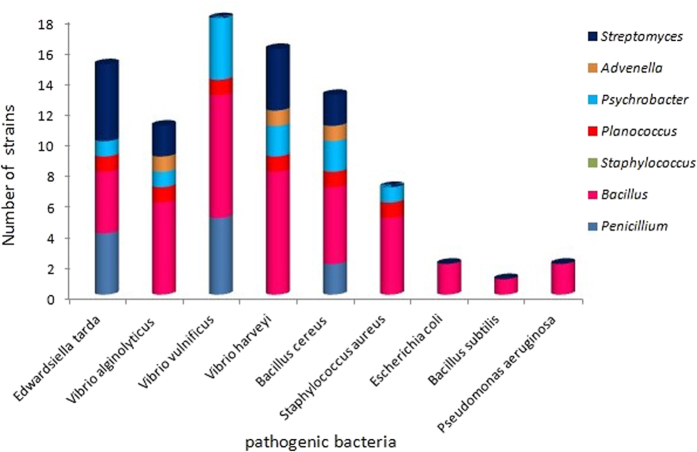

All ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extracts of the 75 isolates were tested for antibacterial activity against six aquatic pathogenic bacteria (Vibrio vulnificus, V. alginolyticus, V. parahemolyticus, V. harveyi, Edwardsiella tarda, Bacillus cereus) and five human pathogenic bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). The bacterial and actinobacterial metabolites from E. superba displayed broad and stronger antibacterial activity than fungal metabolites, and the antibacterial activity focused on inhibition of aquatic pathogenic bacteria, especially V. vulnificus, followed by E. tarda, B. cereus, and V. alginolyticus (Table 4, Figs 6 and 7). Among all the isolates, the genus bacteria of Psychrobacter and Bacillus displayed the best antibacterial activity. Three Bacillus sp. OUCMDZ4186, OUCMDZ4192 and OUCMDZ4208 and one Psychrobacter sp. OUCMDZ4189 were the most active, whose minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against V. vulnificus reached to 31.2, 15.6, 7.8 and 3.9 μg/mL, respectively. The MIC values for Bacillus sp. OUCMDZ4191 against B. cereus, V. alginolyticus and S. aureus, and the Planococcus sp. OUCMDZ4188 against V. vulnificus and E. tarda were 62.5, 125 and 125, 125 and 250 μg/mL, respectively. The MIC values for Psychrobacter sp. OUCMDZ4189 against B. cereus, V. alginolyticus and V. vulnificus, and Psychrobacter sp. OUCMDZ4187 against V. vulnificus were 500, 62.5 and 31.2, and 125 μg/mL, respectively. Streptomyces sp. OUCMDZ4173 and OUCMDZ4174 were active on E. tarda, both with the MIC value of 250 μg/mL. Only a few fungi displayed weak antibacterial activity against E. tarda, V. vulnificus and B. cereus at the concentration of 1000 μg/mL, among which Penicillium sp. OUCMDZ4162 displayed strongest inhibition on V. vulnificus with MIC values of 250 μg/mL.

Table 4. The antibacterial activity of the EtOAc extracts at 1000 μg/mLa , b.

| Order | Family | Genus | Strain No.c | E. tarda | V. vulnificus | V. harveyi | V. alginolyticus | B. cereus | S. aureus | E. coli | B. subtilis | P. aeruginosa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurotiales | Trichocomaceae | Penicillium | OUCMDZ4129 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| OUCMDZ4134 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4139 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4140 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4141 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4162 | − | ++ | − | - | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4163 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4164 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |||||

| Capnodiales | Mycosphaerellaceae | Cladosporium | OUCMDZ4138 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| Streptomycineae | Streptomycetaceae | Streptomyces | OUCMDZ4173 | ++ | − | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| OUCMDZ4174 | + | − | + | + | + | − | - | |||||

| OUCMDZ4176 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4177 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4179 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Bacillales | Bacillaceae | Bacillus | OUCMDZ4186 | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | − | ||

| OUCMDZ4181 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4190 | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4191 | − | +++ | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | ||||

| OUCMDZ4192 | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | ||||

| OUCMDZ4205 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4206 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4207 | ++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4208 | + | +++ | + | + | − | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4211 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||||

| OUCMDZ4213 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4215 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | |||||

| Planococcaceae | Planococcus | OUCMDZ4188 | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | − | |||

| Pseudomonadales | Moraxellaceae | Psychrobacter | OUCMDZ4187 | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| OUCMDZ4189 | − | +++ | + | − | + | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4214 | − | + | − | +++ | + | + | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4218 | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | |||||

| OUCMDZ4219 | − | − | +++ | - | − | − | − | |||||

| Burkholderiales | Alcaligenaceae | Advenella | OUCMDZ4222 | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

a+++ strong: inhibition zone diameter (IZD) ≥18 mm; ++ moderate: IZD = 10–17 mm; +weak: IZD< 10 mm; - non active: IZD = 0 mm. All metabolites didn’t show any activity against Vibrio parahemolyticus and Enterobacter aerogenes.

bIDZs of ciprofloxacin (positive control) at 100 μg/mL were 20, 25, 20, 18, 25, 25 and 15 mm for Edwardsiella tarda, Vibrio vulnificus, V. alginolyticus, V. harveyi, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively.

cFungi, bacteria, and actinobacteria were cultured in the fungal medium 2#, LB medium, and actinobacterial medium 2#, respectively.

Figure 6. The antibacterial activity of different genera microbes from E. superba.

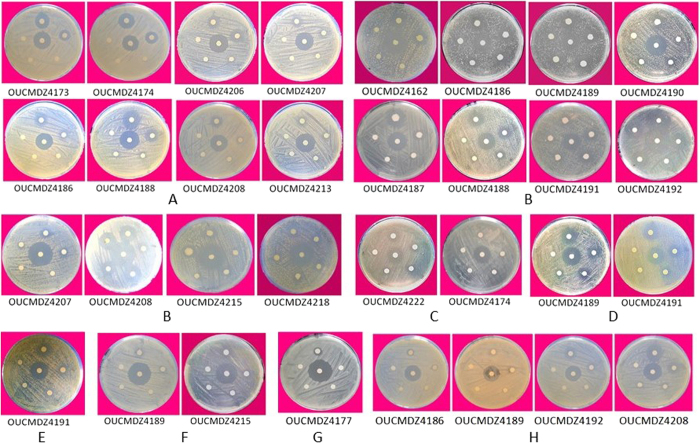

Figure 7. The MIC determination of active strains against aquatic and human pathogenic bacteria.

The middle paper was absorbed the positive drug, and all around papers were absorbed 10 μL samples with different concentration. The numbers such as OUCMDZ4189 were the strain number. The sample concentrations of each paper absorbed clockwise from twelve o’clock corresponded to 1000, 500, 250, 125 and 62.5 μg/mL for A–G and 62.5, 31.25, 15.62, 7.81 and 3.90 μg/mL for H, respectively. (A) against Edwardsiella tarda; (B) against Vibrio vulnificus; (C) against Vibrio harveyi; (D) against Vibrio alginolyticus; (E) against Staphylococcus aureu; (F) against Bacillus cereus; G. against S. aureus in the actinobacterial medium 2# containing 8% NaF, H. against V. vulnificus)

The cytotoxicity

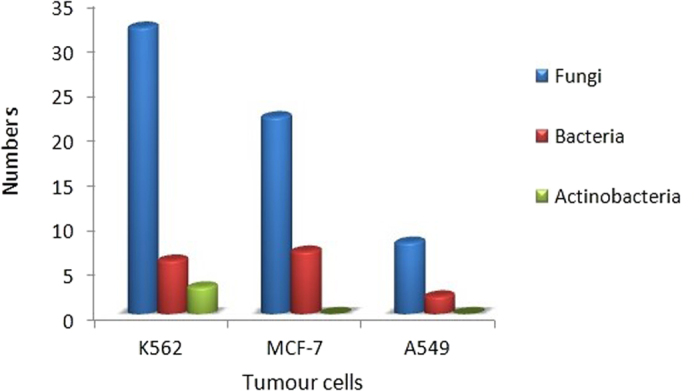

All the EtOAc extracts were also evaluated their cytotoxicities against A549, K562 and MCF-7 tumour cell lines at the concentration of 100 μg/mL. Most of the fungal metabolites displayed more than 60% inhibition against three cell lines, equivalent or near to the adriamycin (positive control); 75%, 72% and 65% inhibitions on the A549, K562 and MCF-7 cell lines, respectively, at the concentration of 1 μM were found for adriamycin (Table 5, Fig. 8). The active strain was defined as those with 60% inhibition at the 100 μg/mL. Additionally, results indicated that 83%, 69% and 19% of the fungal isolates were active against the K562, MCF-7 and A549 cell lines, respectively. However, the Penicillium sp. OUCMDZ4122 showed proliferative effects on A549, K562 and MCF-7 cell lines with −60.0%, −203.3% and −139.5% inhibitions, respectively. The ratios of bacteria to produce active metabolites against K562 were 24%, while 28% was found for the MCF-7 cell line. Very few bacteria produced the cytotoxic metabolites against A549 cell line. Only three actinobacteria produced cytotoxic metabolites to K562 cell line, and these metabolites were not active against A549 and MCF-7 cell lines.

Table 5. Cytotoxicity of the EtOAc extracts of microbial metabolites at 100 μg/mLa , b.

| Strain No.c | K562 (%) | MCF-7 (%) | A549 (%) | Strain No. | K562 (%) | MCF-7 (%) | A549 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUCMDZ4115 | 67.85 ± 1.45 | 63.71 ± 1.46 | - | OUCMDZ4164 | 69.28 ± 2.03 | 65.27 ± 5.89 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4116 | 70.75 ± 1.06 | 77.29 ± 2.73 | 66.19 ± 2.43 | OUCMDZ4166 | 70.75 ± 0.25 | 60.16 ± 1.74 | - |

| OUCMDZ4117 | 69.16 ± 0.47 | 75.27 ± 3.09 | 79.57 ± 1.50 | OUCMDZ4167 | - | 55.39 ± 0.93 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4118 | 67.69 ± 0.51 | 65.04 ± 3.92 | -- | OUCMDZ4168 | 69.18 ± 0.61 | 58.26 ± 1.73 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4120 | 70.32 ± 0.09 | 80.64 ± 1.56 | 82.56 ± 1.72 | OUCMDZ4169 | 68.54 ± 0.84 | 73.27 ± 1.59 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4121 | 69.58 ± 1.74 | 81.94 ± 0.34 | 76.05 ± 5.29 | OUCMDZ4170 | - | - | -- |

| OUCMDZ4122 | −60.04 ± 4.89 | −203.32 ± 16.80 | −139.52 ± 15.91 | OUCMDZ4173 | - | - | -- |

| OUCMDZ4123 | -- | -- | - | OUCMDZ4174 | -- | -- | -- |

| OUCMDZ4124 | 64.49 ± 0.73 | 58.08 ± 1.36 | - | OUCMDZ4176 | 65.18 ± 7.17 | -- | −38.10 ± 3.45 |

| OUCMDZ4125 | 68.88 ± 1.77 | 81.83 ± 1.33 | 81.00 ± 0.54 | OUCMDZ4177 | 69.79 ± 1.64 | -- | - |

| OUCMDZ4126 | 65.88 ± 0.42 | 61.20 ± 1.34 | - | OUCMDZ4179 | 61.21 ± 0.43 | −22.39 ± 14.02 | −25.41 ± 6.49 |

| OUCMDZ4127 | 71.94 ± 0.57 | 57.85 ± 0.18 | - | OUCMDZ4185 | 59.96 ± 9.93 | - | - |

| OUCMDZ4129 | 64.46 ± 1.18 | -- | -- | OUCMDZ4186 | - | 81.46 ± 1.14 | - |

| OUCMDZ4130 | 72.64 ± 1.08 | 75.96 ± 1.20 | 78.23 ± 2.68 | OUCMDZ4187 | 64.12 ± 1.81 | - | −18.24 ± 0.19 |

| OUCMDZ4131 | 55.57 ± 1.66 | -- | -- | OUCMDZ4188 | 62.65 ± 3.47 | 84.41 ± 6.36 | - |

| OUCMDZ4132 | 71.26 ± 0.13 | 76.35 ± 0.92 | 59.32 ± 3.33 | OUCMDZ4189 | 82.35 ± 0.82 | 77.15 ± 2.04 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4133 | 64.73 ± 1.89 | 62.64 ± 1.74 | -- | OUCMDZ4190 | 56.94 ± 4.01 | 78.31 ± 1.23 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4134 | 62.85 ± 0.40 | 59.78 ± 1.25 | - | OUCMDZ4191 | 54.30 ± 2.60 | 68.02 ± 4.83 | 62.75 ± 6.12 |

| OUCMDZ4136 | 67.50 ± 0.60 | 68.62 ± 5.84 | - | OUCMDZ4192 | 52.81 ± 3.03 | 76.56 ± 2.85 | 57.01 ± 4.71 |

| OUCMDZ4137 | 63.87 ± 1.85 | - | -- | OUCMDZ4199 | - | -- | 54.17 ± 11.32 |

| OUCMDZ4138 | 73.24 ± 1.91 | 62.45 ± 7.03 | -- | OUCMDZ4202 | 57.28 ± 9.45 | -- | -- |

| OUCMDZ4139 | 64.10 ± 1.11 | -- | -- | OUCMDZ4205 | - | - | - |

| OUCMDZ4140 | 60.86 ± 3.46 | 53.67 ± 5.15 | -- | OUCMDZ4206 | 68.36 ± 1.26 | -- | 61.81 ± 1.92 |

| OUCMDZ4141 | 57.71 ± 8.11 | 71.73 ± 2.31 | -- | OUCMDZ4207 | 56.76 ± 4.74 | 54.91 ± 2.54 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4143 | 69.14 ± 0.79 | 61.23 ± 2.19 | -- | OUCMDZ4208 | -- | 53.05 ± 0.78 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4145 | 68.94 ± 1.09 | 81.36 ± 0.31 | - | OUCMDZ4210 | -- | 52.98 ± 1.05 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4149 | - | -- | -- | OUCMDZ4211 | 65.67 ± 1.86 | 58.85 ± 7.02 | 53.82 ± 0.98 |

| OUCMDZ4150 | 63.98 ± 3.15 | -- | -- | OUCMDZ4212 | -- | -- | -- |

| OUCMDZ4151 | - | -- | -- | OUCMDZ4213 | 77.65 ± 2.96 | 65.85 ± 0.80 | 54.08 ± 8.42 |

| OUCMDZ4152 | - | -- | - | OUCMDZ4218 | -- | 58.26 ± 6.04 | -- |

| OUCMDZ4154 | 71.98 ± 0.35 | 52.09 ± 1.83 | 75.97 ± 0.35 | OUCMDZ4214 | - | -- | -- |

| OUCMDZ4155 | - | -- | - | OUCMDZ4215 | - | - | - |

| OUCMDZ4156 | 65.99 ± 2.90 | 57.00 ± 2.69 | - | OUCMDZ4219 | -- | - | -- |

| OUCMDZ4161 | 66.93 ± 4.16 | 60.98 ± 0.35 | - | OUCMDZ4220 | -- | −54.84 ± 9.91 | −116.64 ± 8.18 |

| OUCMDZ4162 | 61.86 ± 0.12 | 62.05 ± 6.69 | - | OUCMDZ4221 | -- | -- | -- |

| OUCMDZ4163 | 72.19 ± 0.36 | 73.25 ± 5.32 | 63.43 ± 7.16 | OUCMDZ4222 | - | - | - |

| OUCMDZ4183 | 59.23 ± 1.28 | -- | - | OUCMDZ4181 | -- | -- | -- |

| OUCMDZ4182 | - | - | - |

aEach datum represents the average inhibition and the standard deviation of three independent experiment: <50% inhibition (-, weak), <30% inhibition (--, very weak).

bThe inhibitions of adriamycin (positive control) at 1 μM for K562, MCF-7 and A549 were 72%, 65% and 75%, respectively.

cFungal strains OUCMDZ4115–4170 were cultured in the fungal medium 2#; Bacteria strains OUCMDZ4185–4219, 4181, 4221 and 4222 were cultured in the LB medium; Actinobacterial strains OUCMDZ4173–4179, 4182, 4183 and 4220 were cultured in the actinobacterial medium 2#.

Figure 8. The quantities of active strains (≥ 60% inhibition at 100 μg/mL) from E. superba against K562, MCF-7 and A549 tumor cell lines.

NaF tolerance of microbes and the corresponding bioactivity

In order to verify whether the microbial isolates were from the Antarctic krill, the NaF tolerances of all the 75 isolates were evaluated by adding different concentrations of NaF into the media. The maximum NaF tolerance concentration of actinobacteria, bacteria and fungi reached to 10% (in actinobacterial medium 2#), 3% (in LB medium) and 0.5% (in fungal medium 2#) (Tables 6, 7 and 8). The bioactive screening indicated that adding NaF had a significant effect on metabolites. After adding NaF into the media, the microbes reduced the production of antimicrobial products toward the tested pathogenic bacteria, the exception being Streptomyces sp. OUCMDZ4177, where metabolites were active at 1 mg/mL against S. aureus under the actinobacterial medium 2# containing 8% NaF (Fig. 7G). This is consistent with the fact that fluoride is toxic to microorganisms especially in high concentrations. Thus, the fluoride-tolerant microorganisms might reduce the yield of the anti-pathogenic bacterial compounds in such high NaF media. Although only one actinobacterial isolate produced the antibacterial metabolites under NaF, the cytotoxicity of the actinobacterial metabolites under NaF increased. For example, nearly all of the actinobacterial metabolites under 2%, 3%, 8% and 10% NaF displayed more than 50% inhibition on MCF-7 cells (Table 9). However, the secondary metabolites of bacteria under NaF did not show cytotoxicities. And the eight fungi produced the cytotoxic metabolites against three tumor cell lines under 0.5% NaF (Table 10). Among them, Penicillium citrinum OUCMDZ4136 was selected for further chemical study by producing the strongest cytotoxic metabolites against three tumor cells in the SWS medium (Table 1) containing 0.5% NaF. Chemical studies led to the identification of seven compounds (1–7). These compounds did not show antibacterial activity towards 11 pathogenic bacteria but showed pronounced cytotoxicity against MCF-7, A549 and K562 tumor cells with the IC50 values ranging from 2.2 to 19.8 μM (Table 11), further indicating that krill microbes continue to produce cytotoxic compounds under a fluoride media.

Table 6. The production of the fungal metabolites in the fungal medium 2# (mg/mL).

| Strain No. | Without NaF | 0.5% NaF | Strain No. | Without NaF | 0.5% NaF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUCMDZ4115 | 0.323 | 0.080 | OUCMDZ4139 | 0.487 | 0.013 |

| OUCMDZ4116 | 0.553 | 0.012 | OUCMDZ4140 | 0.082 | 0.079 |

| OUCMDZ4117 | 0.573 | 0.167 | OUCMDZ4141 | 0.451 | 0.189 |

| OUCMDZ4118 | 0.485 | 0.102 | OUCMDZ4143 | 0.550 | 0.208 |

| OUCMDZ4120 | 0.718 | 0.269 | OUCMDZ4145 | 0.348 | 0.054 |

| OUCMDZ4121 | 0.583 | 0.173 | OUCMDZ4149 | 0.253 | 0.013 |

| OUCMDZ4122 | 0.177 | 0.071 | OUCMDZ4150 | 0.413 | 0.044 |

| OUCMDZ4123 | 0.368 | 0.128 | OUCMDZ4151 | 0.248 | 0.076 |

| OUCMDZ4124 | 0.591 | 0.244 | OUCMDZ4152 | 0.315 | 0.184 |

| OUCMDZ4125 | 0.425 | 0.156 | OUCMDZ4154 | 0.259 | 0.192 |

| OUCMDZ4126 | 0.662 | 0.256 | OUCMDZ4155 | 0.376 | 0.155 |

| OUCMDZ4127 | 0.439 | 0.107 | OUCMDZ4156 | 0.547 | 0.108 |

| OUCMDZ4129 | 0.779 | 0.138 | OUCMDZ4161 | 0.267 | 0.034 |

| OUCMDZ4130 | 0.055 | 0.037 | OUCMDZ4162 | 0.533 | 0.196 |

| OUCMDZ4131 | 0.901 | 0.329 | OUCMDZ4163 | 0.519 | 0.150 |

| OUCMDZ4132 | 0.645 | 0.281 | OUCMDZ4164 | 0.692 | 0.244 |

| OUCMDZ4133 | 0.636 | 0.213 | OUCMDZ4166 | 0.511 | 0.034 |

| OUCMDZ4134 | 0.647 | 0.335 | OUCMDZ4167 | 0.413 | 0.214 |

| OUCMDZ4136 | 0.515 | 0.128 | OUCMDZ4168 | 0.393 | 0.019 |

| OUCMDZ4137 | 0.038 | 0.029 | OUCMDZ4169 | 0.687 | 0.021 |

| OUCMDZ4138 | 0.507 | 0.144 | OUCMDZ4170 | 0.265 | 0.099 |

Table 7. The production of the bacterial metabolites in the LB medium (mg/mL).

| Strain No. | Without NaF | 3% NaF | Strain No. | Without NaF | 3% NaF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUCMDZ4186 | 0.299 | 0.015 | OUCMDZ4208 | 0.349 | 0.025 |

| OUCMDZ4187 | 0.185 | 0.030 | OUCMDZ4210 | 0.283 | 0.013 |

| OUCMDZ4188 | 0.042 | 0.002 | OUCMDZ4211 | 0.250 | 0.002 |

| OUCMDZ4189 | 0.382 | 0.019 | OUCMDZ4212 | 0.201 | 0.013 |

| OUCMDZ4190 | 0.095 | 0.005 | OUCMDZ4213 | 0.143 | 0.006 |

| OUCMDZ4191 | 0.067 | 0.002 | OUCMDZ4218 | 0.067 | 0.008 |

| OUCMDZ4192 | 0.331 | 0.015 | OUCMDZ4214 | 0.233 | 0.016 |

| OUCMDZ4199 | 0.025 | 0.003 | OUCMDZ4215 | 0.185 | 0.006 |

| OUCMDZ4202 | 0.080 | 0.001 | OUCMDZ4219 | 0.621 | 0.005 |

| OUCMDZ4205 | 0.257 | 0.004 | OUCMDZ4185 | 0.260 | 0.025 |

| OUCMDZ4206 | 0.215 | 0.002 | OUCMDZ4221 | 0.164 | 0.003 |

| OUCMDZ4207 | 0.113 | 0.006 | OUCMDZ4222 | 0.215 | 0.004 |

| OUCMDZ4181 | 0.173 | 0.008 |

Table 8. The production of the actinobacterial metabolites in the actinobacterial medium 2# (mg/mL).

| Strain No. | Without NaF | 2% NaF | 3% NaF | 8% NaF | 10% NaF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUCMDZ4173 | 0.698 | 0.188 | 0.089 | 0.047 | 0.026 |

| OUCMDZ4174 | 0.289 | 0.077 | 0.043 | 0.034 | 0.017 |

| OUCMDZ4176 | 0.427 | 0.038 | 0.068 | 0.015 | 0.032 |

| OUCMDZ4177 | 0.350 | 0.058 | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| OUCMDZ4179 | 0.129 | 0.029 | 0.024 | 0.019 | 0.016 |

| OUCMDZ4182 | 0.206 | 0.024 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.011 |

| OUCMDZ4183 | 0.192 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| OUCMDZ4220 | 0.287 | 0.082 | 0.053 | 0.019 | 0.009 |

Table 9. Cytotoxicity of the EtOAc extracts of actinobacterial metabolites under NaFa , b.

| Strain No.c | K562 (%) | 2% NaF |

3% NaF |

8% NaF |

10% NaF |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7(%) | A549 (%) | K562 (%) | MCF-7(%) | A549 (%) | K562 (%) | MCF-7(%) | A549 (%) | K562 (%) | MCF-7(%) | A549 (%) | ||

| OUCMDZ4173 | 32.88 ± 0.04 | 63.96 ± 0.17 | −4.55 ± 0.37 | 48.50 ± 0.06 | 69.97 ± 0.28 | −6.81 ± 0.02 | −4.53 ± 0.19 | 45.53 ± 0.11 | 7.89 ± 0.09 | 2.47 ± 0.07 | 67.20 ± 0.09 | 18.25 ± 0.01 |

| OUCMDZ4174 | 6.99 ± 0.12 | 58.46 ± 0.07 | 29.64 ± 0.05 | 58.54 ± 0.23 | 54.43 ± 0.03 | −6.63 ± 0.24 | 11.36 ± 0.45 | 27.62 ± 0.18 | 43.90 ± 0.08 | −3.55 ± 0.83 | 63.23 ± 0.29 | 17.39 ± 0.09 |

| OUCMDZ4176 | 9.73 ± 0.07 | 76.67 ± 0.38 | 29.73 ± 0.36 | −2.51 ± 0.59 | 71.91 ± 0.54 | 13.80 ± 0.04 | 36.81 ± 0.36 | 66.83 ± 0.65 | 36.64 ± 0.13 | 4.08 ± 0.58 | 72.68 ± 0.04 | 28.20 ± 0.06 |

| OUCMDZ4177 | 8.43 ± 0.03 | 56.66 ± 0.01 | 13.86 ± 0.08 | 43.68 ± 0.56 | 46.93 ± 0.37 | 31.90 ± 0.12 | 1.82 ± 0.56 | 51.40 ± 0.05 | 10.15 ± 0.06 | 5.02 ± 0.54 | 51.79 ± 0.11 | 35.47 ± 0.15 |

| OUCMDZ4179 | 21.67 ± 0.16 | 32.40 ± 0.92 | 42.81 ± 0.81 | 26.88 ± 0.04 | 74.63 ± 0.08 | −282.72 ± 0.73 | 29.29 ± 0.62 | 63.17 ± 0.06 | 22.74 ± 0.06 | 1.62 ± 0.53 | 75.98 ± 0.012 | 13.51 ± 0.01 |

aEach datum represents the average inhibition and the standard deviation of three independent experiment.

bThe inhibitions of adriamycin (positive control) at 1 μM for K562, MCF-7 and A549 were 73%, 71% and 74%, respectively.

cCultured in the actinobacterial medium 2#.

Table 10. Cytotoxicity of the EtOAc extracts of fungal metabolites under 0.5% NaFa,b.

| Strain No. | K562 (%) | Fungal medium 2# |

SWS medium |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 (%) | A549 (%) | K562 (%) | MCF-7 (%) | A549 (%) | ||

| OUCMDZ4118 | 79.32 ± 0.18 | 86.23 ± 0.25 | 84.15 ± 0.01 | 79.71 ± 0.61 | 60.19 ± 0.01 | 61.41 ± 0.01 |

| OUCMDZ4122 | 62.90 ± 0.33 | 79.23 ± 0.37 | 79.16 ± 0.07 | 85.06 ± 0.82 | 63.99 ± 0.14 | 61.53 ± 0.03 |

| OUCMDZ4130 | 57.19 ± 0.65 | 84.49 ± 0.004 | 85.09 ± 0.72 | 85.65 ± 1.12 | 64.06 ± 0.02 | 57.35 ± 0.17 |

| OUCMDZ4131 | 17.36 ± 0.07 | 76.61 ± 0.01 | 63.97 ± 0.002 | 3.89 ± 0.03 | 49.85 ± 0.02 | 1.91 ± 0.49 |

| OUCMDZ4134 | 63.20 ± 0.52 | 87.40 ± 0.07 | 75.72 ± 0.05 | 89.37 ± 0.02 | 72.25 ± 0.21 | 77.72 ± 0.02 |

| OUCMDZ4136 | 40.90 ± 0.34 | 75.35 ± 0.06 | 65.77 ± 0.01 | 87.70 ± 0.19 | 80.00 ± 0.02 | 66.61 ± 0.07 |

| OUCMDZ4137 | 80.86 ± 0.01 | 61.68 ± 0.22 | 73.00 ± 0.25 | 26.73 ± 1.07 | 66.88 ± 0.24 | 50.59 ± 0.01 |

| OUCMDZ4145 | 50.36 ± 0.66 | 88.07 ± 0.45 | 87.74 ± 0.01 | 12.59 ± 4.10 | 55.43 ± 0.04 | 64.87 ± 0.21 |

aEach datum represents the average inhibition and the standard deviation of three independent experiment.

bThe inhibitions of adriamycin (positive control) at 1 μM for K562, MCF-7 and A549 were 87%, 60% and 83%, respectively.

Table 11. Cytotoxicity of seven compounds from P. citrinum OUCMDZ4136 under 0.5% NaFa.

| Compounds | MCF-7 (IC50/μM) | A549 (IC50/μM) | K562 (IC50/μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.29 ± 0.12 | 7.10 ± 0.04 | 10.75 ± 0.03 |

| 2 | 3.60 ± 0.03 | 2.20 ± 0.06 | 5.43 ± 0.022 |

| 3 | 6.10 ± 0.13 | 5.60 ± 0.02 | 7.80 ± 0.12 |

| 4 | 4.20 ± 0.06 | 13.90 ± 0.05 | 13.50 ± 0.03 |

| 5 | 6.50 ± 0.02 | >100 | 15.37 ± 0.06 |

| 6 | 13.15 ± 0.05 | 19.80 ± 0.09 | 12.60 ± 0.03 |

| 7 | 3.92 ± 0.02 | 3.00 ± 0.17 | 8.96 ± 0.16 |

| Adriamycin | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 1.38 ± 0.11 | 0.34 ± 0.01 |

aEach datum represents the average and the standard deviation of three independent experiment.

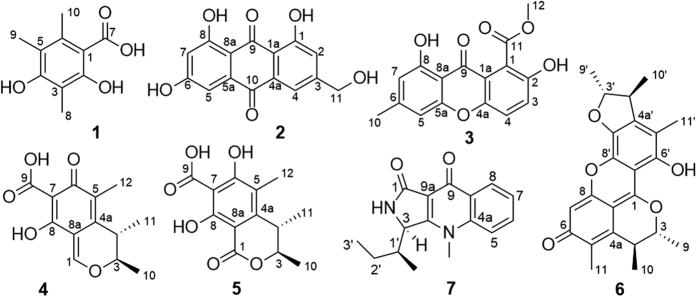

Compounds from Penicillium citrinum OUCMDZ4136

Seven compounds were isolated from the fermentation broth of P. citrinum OUCMDZ4136 in the SWS medium containing 0.5% NaF. By comparison of NMR and specific rotation data with those reported, their structures were identified as 2,4-dihydroxy-3,5,6-trimethylbenzoic acid (1)13,14, citreorosein (2)15,16, pinselin (3)17, citrinin (4)18,19,20, dihydrocitrinone (5)21,22, pennicitrinone A (6)23,24 and quinolactacin A1 (7)25, respectively (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. The chemical structures of the identified seven compounds.

Discussion and Conclusion

Both pathogenic bacteria Edwardsiella tarda and Vibrio vulnificus are common, serious and even fatal aquatic pathogenic bacteria26,27. These infections seriously threaten aquatic agriculture and lead to serious ecological losses in the aquatic area. Pathogenic bacteria also have a wide host distribution in the Antarctic region28, typically causing intestinal disease and wound infections in many organisms including marine life and humans29,30,31. E. superba appears to have developed an immune system to avoid or restrain the invasion of aquatic pathogenic bacteria and other organisms. For example, Antarctic krill enzymes had significant effect on treating venous leg ulcer and could fast promote wound healing when compared with the non-enzymes control32. In addition, microorganisms from E. superba may participate in the chemical defense of the host through the production of antibacterial and/or cytotoxic metabolites. Our results indicated that the microbial isolates produced antibacterial metabolites against E. tarda, V. vulnificus, V. harveyi, V. alginolyticus, B. cereus, S. aureus and E. coli were 17, 17, 15, 9, 13, 8, and 2 strains, respectively. Additionally, the microbes that produced the cytotoxic metabolites with more than 60% inhibitions to K562, MCF-7 and A549 cell lines were 41, 29 and 10 strains, respectively. Even in the condition of the NaF, most of the actinobacteria and some fungi still produce cytotoxic products. For example, compounds 1–7 from the metabolites of P. citrinum OUCMDZ4136 under 0.5% NaF displayed moderate to strong cytotoxicity against A549, K562 and MCF-7 tumour cells. These results provide scientific evidence that microbes from E. superba participate in the protection of their host by producing antibacterial metabolites to pathogenic and cytotoxic metabolites for predatory mammals even under the high concentration of NaF.

In conclusion, a total 75 microbial isolates were identified from E. superba collected in the Antarctic area FAO48.1. The phylogenetic relationships of these culturable microorganisms on the basis of gene sequences were constructed successfully. This construction revealed diverse krill-associated microbes including four phyla, seven classes, seven orders, nine families and 11 genera. All isolates were able to survive under NaF, and the NaF endurance ranged from 0.5% to 10%. These krill microbes could metabolize the antibacterial and cytotoxic products in the media without NaF, but mainly produced cytotoxic compounds under NaF. This study proves that symbiotic microbes may use their cytotoxic and antibacterial metabolites as the chemical weapon to protect their host in addition to receiving a nutritional benefit from the host.

Methods

General experimental procedures

The sample of the Antic krill strains were isolated from Euphausia superba collected from the Southern Ocean FAO48.1 (50–65°W, 50–65°S) (Fig. S77) in February 2010. The purified strains were submitted to the Identification Service of BGI tech (Beijing, China) for sequencing. The phylogenic relationships on the basis of gene sequences were analyzed. At the same time, the assay of NaF tolerance and anti-bacterial and cytotoxic activity were carried out. The aquatic pathogenic bacteria, Edwardsiella tarda (ATCC 15947), Vibrio parahemolyticus (ATCC 17802), V. vulnificus (ATCC 27562), V. harveyi (ATCC 14126), V. alginolyticus (ATCC 17749) and Bacillus cereus (ATCC 14579), the human pathogenic bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538), Escherichia coli (ATCC 11775), Enterobacter aerogenes (ATCC 13048), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6051) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145), were purchased from the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Science, and Guangdong Institute of Microbiology. Nucleotide sequences were measured using an ABI3730XL sequencing apparatus. IR spectra were taken using a Nicolet NEXUS 470 spectrophotometer as KBr disks. UV spectrum data were obtained on a UH5300 spectrophotometer. Specific rotations were determined by a JASCO P-1020 digital polarimeter. CD data were obtained on a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter. 1H, 13C and DEPTQ NMR spectra of compounds 1–7 were recorded by Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer using TMS as internal standard, and chemical shifts were recorded as δ values that were further referenced to residual solvent signals for DMSO (δH/δC, 2.50/39.5). ESIMS data were recorded by a Q-TOF ULTIMA GLOBAL GAA076 LC mass spectrometer. TLC and column chromatography (CC) and vacuum-liquid chromatography (VLC) were performed on plates precoated with silica gel GF254 (10ica μm) and silica gel (200cate mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory) and Sephadex LH-20 (Amersham Biosciences), respectively. HPLC and semi-preparative HPLC were performed using a Cholester column (YMC-pack, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, 1 mL/min) and an ODS column [YMC-pack ODS-A, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm, 4 mL/min], respectively.

The isolations of Antarctic krill microbes

The E. superba (1.0 g) were leached with sterile seawater three times under sterile conditions to remove superficial sediments and microbes. The specimen was then homogenized and diluted with sterile seawater into three different concentrations (0.1, 0.01 and 0.001), 100 μL of each dilution were plated onto the corresponding isolation medium (Table 1) in triplicate. Chloramphenicol (100 μg/mL) was added into the medium to prohibit the growth of bacteria during the cultivation of actinobacteria and fungi. The inoculated plates of actinobacteria and bacteria were propagated at 4 or 16 °C for 3–90 d, whereas the fungi isolates were cultured at 4, 16, 25 or 28 °C for at least 5 d. If the colony could not be observed at 4 °C during three months, the next temperature was selected till the colony was visible. All microorganisms of the single colony were isolated, then inoculated onto a slope media and stored in a 4 °C refrigerator. Additionally, the same strains were preserved in 20% glycerine liquid medium at −80 °C for the future use.

Microbial identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR amplification were conducted by BGI (The Beijing Genomics Institute, www.genomics.org.cn). The purified PCR product was sequenced bidirectionally on an ABI 3703 automated sequenator. The sequences contigs were edited by Bioedit 7.0.9.0 and MEGA 6.06 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis) software. The obtained sequences were deposited in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) Genebank database under accession number arranging from KU216704 to KU216743, from KU291358 to KU291375 and from KU579260 to KU579276. The obtained sequences were aligned in NCBI Genebank database with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (http:// blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) in order to confirm the maximum similarity sequences. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA 6.06 based on Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method 33.

The investigation of NaF tolerance

All isolates from E. superba were evaluated their NaF-tolerance by adding NaF into the media at concentrations of 12%, 10%, 8%, 3%, 2%, 0.5% and 0% (control). The strains were incubated as following the fermentation procedures. All the incubations were monitored and compared with the control every 12 h. The fermentation broth was extracted three times with an equal volume of EtOAc and the whole EtOAc solutions were evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and weighed (Tables 6, 7 and 8).

Sample preparations for bioassay

The 75 microbial isolates were fermented under two different conditions with and without NaF. The bacteria were shaking at 4 °C, 180 rpm for 3 d in a 500 mL conical flask containing 150 mL LB liquid medium (Table 1). The actinobacterial were shaking at 4 °C, 180 rpm for 7 d in a 500 mL conical flask containing 150 mL liquid actinobacterial medium 2# (Table 1). The fungi were statically cultivated at 16 °C for 60 d in a 1000 mL conical flask containing 300 mL liquid fungal medium 2# (Table 1). The amounts of NaF added were 0.5% for fungi, 3% for bacteria, and 2%, 3%, 8%, and 10% for actinobacteria. Each experiment was conducted in three parallels. The fermentation broth was extracted three times with an equal volume of EtOAc and the whole EtOAc solutions were evaporated under reduced pressure to give the dried extracts for bioassay.

Compounds isolation and identification

Penicillium citrinum OUCMDZ4136 was fermented under static conditions at 16 °C for 60 days in three hundred 1000 mL Erlenmeyer flasks each with 300 mL SWS liquid medium (Table 1) containing 0.5% NaF (Fig. S76). The harvested fermentation broths (27 L) were extracted thrice with equal volume of EtOAc that gave 10.3 g EtOAc extracts after removal of the solvents in vacuum. All extracts were separated by a silica-gel column eluting solution with petroleum ether–EtOAc (v/v1:0, 1:1) and then CH2Cl2-MeOH (v/v 1:0, 50:1, 30.1, 20:1, 10:1, 1:1 and 0:1) to get nine subfractions (Fr.1–Fr.9). The cytotoxic fraction 2 (218.9 mg) was subjected to isolation over a Sephadex LH-20 column eluting with MeOH to give twenty-five subfractions (Fr.2–1–Fr.2–25). Fr.2–12 (130.5 mg) was further separated by a Sephadex LH-20 column eluting with MeOH to give twenty subfractions (Fr.2–12–1–Fr.2–12–20). The active Fr.2-12-15 (89.3 mg) was further subjected to purification with HPLC ODS column (v/v MeOH−H2O 7:3) to yield compounds 3 (4.72 mg, tR 10.5 min), 4 (9.96 mg, tR 4.9 min), and 5 (5.93 mg, tR 5.5 min). Fr.2–21 (35.6 mg) was further purified by semi-preparative HPLC over ODS column eluting with MeOH-H2O-CF3CO2H (v/v 70:30:0.15) to give compounds 1 (3.30 mg, tR 5.1 min) and 2 (4.25 mg, tR 6.9 min). The second cytotoxic fraction (Fr.8, 20.9 mg) was isolated by a Sephadex LH-20 column eluting with CH2Cl2-MeOH (v/v 1:1) to obtain thirty fractions. The main fraction (Fr.8-20, 13.4 mg) was further purified by HPLC ODS column (v/v MeCN-H2O 4:6) to yield compound 7 (8.39 mg, tR 4.8 min). Fr.4 (89.7 mg) and Fr.5 (58.3 mg) were combined and separated over Sephadex LH-20 column eluting with CH2Cl2-MeOH (v/v 1:1) to give eight subfractions (Fr.4-1–Fr.4-8). The Fr.4-3 (33.7 mg) was further purified by semi-preparative HPLC over ODS column (v/v MeOH−H2O-CF3CO2H 60:40:0.15) to yield compound 6 (2.9 mg, tR 13.1 min).

2,4-Dihydroxy-3,5,6-trimethylbenzoic acid (1)

yellow white powder; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 257 (3.13), 264 (2.02), 213 (4.13) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3424, 2361, 1683, 1207, 1140 cm−1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 2.00 (s, 3H, H-8), 2.04 (s, 3H, H-9), 2.38 (s, 3H, H-10). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 106.7 (qC, C-1), 159.1 (qC, C-2), 108.2 (qC, C-3), 157.2 (qC, C-4), 115.3 (qC, C-5), 136.5 (qC, C-6), 174.2 (qC, C-7), 9.0 (CH3, C-8), 12.3 (CH3, C-9), 18.3 (CH3, C-10); ESI-MS m/z 197.96 [M + H]+.

Citreorosein (2)

yellow amorphous solid; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 437 (2.63), 289 (4.12), 267 (4.02) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3083, 1682, 1571, 1398, 1212, 762 cm−1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 7.22 (s, 1H, H-2), 7.61 (s, 1H, H-4), 7.09 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H, H-5), 6.57 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H, H-7), 4.59 (s, 2H, H-11), 12.0 (s, 2H, 1/8-OH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 164.5 (qC, C-1), 120.8 (CH, C-2), 152.9 (qC, C-3), 117.1 (CH, C-4), 133.0 (qC, C-4a), 109.0 (CH, C-5), 135.2 (qC, C-5a), 161.5 (qC, C-6), 108.0 (CH, C-7), 165.8 (qC, C-8), 109.0 (qC, C-8a), 189.7 (qC, C-9), 181.4 (qC, C-10), 62.1 (CH2, C-11); HRESIMS m/z [M + H]+ 287.0545.

Pinselin (3)

reddish brown amorphous powder; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 384 (1.27), 290 (1.85), 263 (3.82) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2361, 1208, 1683 cm−1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 7.48 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 7.61 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H-4), 6.89 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.64 (s, 1H, H-7), 2.39 (s, 3H, H-10), 3.84 (s, 3H, H-11). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 117.1 (qC, C-1), 117.2 (qC, C-1a), 150.8 (qC, C-2), 125.4 (CH, C-3), 120.1 (CH, C-4), 149.4 (qC, C-4a), 107.4 (CH, C-5), 155.5 (qC, C-5a), 149.4 (qC, C-6), 110.8 (CH, C-7), 160.4 (qC, C-8), 106.0 (qC, C-8a), 180.3 (qC, C-9), 22.1 (CH3, C-10), 167.3 (qC, C-11), 52.3 (CH3, C-12); HRESIMS m/z 301.0704 [M + H]+.

Citrinin (4)

yellow needle crystal; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 391 (1.31), 256 (2.56), 223 (4.45) nm; [α]D25−19.6 (c 0.35, MeOH); CD (c 0.02 M, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 372 (−8.05), 311 (+13.92), 273 (+1.92), 265 (+2.54), 250 (−1.45) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3446, 2361, 1623,1610 cm−1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 8.61 (s, 1H, H-1), 4.98 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.20 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H-4), 1.26 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H, H-10), 1.13 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, H-11), 1.96 (s, 3H, H-12). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.9 (CH, C-1), 80.1 (CH, C-3), 33.5 (CH, C-4), 141.1 (qC, C-4a), 121.3 (qC, C-5), 182.6 (qC, C-6), 99.5 (qC, C-7), 176.5 (qC, C-8), 106.6 (qC, C-8a), 174.2 (qC, C-9), 17.6 (CH3, C-10), 18.0 (CH3, C-11), 9.1 (CH3, C-12); ESI-MS m/z 251.2 [M + H]+.

Dihydrocitrinone (5)

yellow powder; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 323 (2.75), 254 (2.42) nm; [α]D25 +42.7 (c 0.18 MeOH); CD (c 0.019 M, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 338.5 (−2.86), 271 (+19.83), 266 (+19.27), 236 (+7.06); IR (KBr) νmax 2977, 2361, 1653, 1596, 1402 cm−1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 4.61 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.07 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, H-4), 1.19 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H, H-10/11), 2.02 (s, 3H, H-12). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 165.6 (qC, C-1), 78.2 (CH, C-3), 34.2 (CH, C-4), 146.9 (qC, C-4a), 112.9 (qC, C-5), 166.4 (qC, C-6), 101.4 (qC, C-7), 163.6 (qC, C-8), 99.0 (qC, C-8a), 173.4 (qC, C-9), 18.9 (CH3, C-10), 19.6 (CH3, C-11), 9.7 (CH3, C-12); ESI-MS m/z 267.2 [M + H]+.

Pennicitrinone A (6)

orange yellow powder; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 206 (0.558), 276 (0.759), 422 (0.726) nm; [α]D25 +66.5 (c 0.1 CHCl3); CD (c 0.013 M, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 419 (+9.42), 324 (−5.93), 301 (+4.40), 244 (−0.39) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3470, 2340, 1204, 1663, 1652 cm−1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 5.35 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.43 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, H-4), 6.76 (s, 1H, H-7), 1.33 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H, H-9), 1.23 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, H-10), 2.13 (s, 3H, H-11), 4.70 (dq, J = 3.5, 6.5 Hz,1H, H-3′), 3.34 (dq, J = 3.5, 6.9 Hz, 1H, H-4′), 1.33 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H, H-9′), 1.27 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, H-10′), 2.23 (s, 3H, H-11′); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 169.8 (qC, C-1), 84.2 (CH, C-3), 33.7 (CH, C-4), 136.4 (qC, C-4a), 125.9 (qC, C-5), 173.9 (qC, C-6), 100.1 (CH, C-7), 157.7 (qC, C-8), 101.5 (qC, C-8a), 18.4 (CH3, C-9), 18.9 (CH3, C-10), 10.3 (CH3, C-11), 87.9 (CH, C-3′), 44.3 (CH, C-4′), 143.6 (qC, C-4a′), 118.7 (qC, C-5′), 148.9 (qC, C-6′), 104.3 (qC, C-7′), 136.8 (qC, C-8′), 137.4 (qC, C-8a′), 20.8 (CH3, C-9′), 18.9 (CH3, C-10′), 12.1 (CH3, C-11′); ESI-MS m/z 379.17 [M - H]−.

Quinolactacin A1 (7)

white solid. UV (MeOH) λmax (logε) 315(3.09), 371(1.18), 236(3.52) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2340, 1204, 1663, 1652; [α]D25 +28.5(c 0.1 CHCl3), 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 4.94 (s, 1H, H-3), 3.80 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 8.00 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.89 (dd, J = 8.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.58 (dd, J = 7.6, 7.7 Hz, 1H, H-7), 8.23 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, H-8), 2.20 (m, 1H, H-1′), 0.43 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H, 1’-CH3), 1.39 (m, 1H, H-2′), 1.59 (m, 1H, H-2′), 1.00 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 3H, H-3′). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 169.0 (qC, C-1), 57.9 (CH, C-3), 163.9 (qC, C-3a), 35.8 (CH3, N-CH3), 141.5 (qC, C-4a), 118.4 (CH, C-5), 133.6 (CH, C-6), 126.0 (CH, C-7), 126.1 (CH, C-8), 130.2 (qC, C-8a), 170.8 (qC, C-9), 107.8 (qC, C-9a), 35.8 (CH, C-1′), 11.7 (CH3, 1′-CH3), 27.4 (CH2, C-2′), 12.0 (CH3, C-3′).

Evaluation for antibacterial activity

A paper disk-agar diffusion method34 was applied into the antibacterial assay against six aquatic pathogenic bacteria (E. tarda, V. parahemolyticus, V. vulnificus, V. harveyi, V. alginolyticus, and B. cereus) and five human pathogenic bacteria (S. aureus, E. coli, E. aerogenes, B. subtilis, and P. aeruginosa). The initial concentration of sample was 1.0 mg/mL for EtOAc extracts and 0.1 mg/mL for compounds. Ciprofloxacin with the concentration of 0.1 mg/mL was used as a positive control. Pathogenic bacteria were inoculated into a 50 mL tube containing 20 mL liquid medium and shaken at 28 °C and 180 rpm. Aquatic pathogenic bacteria were cultured in 2216E medium for 24 h, human pathogenic bacteria were cultured in LB liquid media for 12 h. The bacteria suspension was coated on the corresponding agar plate, and cultured at room temperature for 30 min. Paper discs that absorbed 10 μL of sample and positive control solution were volatilized to dry and placed onto the agar plate coated with the bacterial suspension. Every sample was tested based on three parallels. The bacterial static plates were incubated for 12 h at 28 °C. The inhibition zone was observed every hour for 16 h and the inhibition zone diameters were recorded (Table 4 and Fig. 6). Once the antibacterial activity was observed, the MIC value was measured by conventional serious two-fold agar dilution methods. The MIC was defined as the lowest corresponding concentration adsorbed in paper around which no bacterial growth was observed. The solution of 1.0 mg/mL was further diluted to 500, 250, 125, and 62.5 μg/mL (Fig. 7A–G). If the inhibition zone could still be observed, the solution of 62.5 μg/mL was further diluted to 31.25, 15.62, 7.81, and 3.90 μg/mL (Fig. 7H).

Cytotoxic Assay

Cytotoxicities for MCF-7 and A549, and for K562 cell lines (Table 5) were evaluated by MTT35 and CCK-836 methods, respectively. The EtOAc extracts, compounds and adriamycin (the positive control) were dissolved in DMSO with the concentration of 2 mg/mL, 2 mM, and 0.2 mM, respectively. Then, 10 μL of the DMSO solution was diluted into 990 μL RPMI-1640 medium and the testing solution was formulated as 200 μg/mL for EtOAc extracts, 20 μM for compounds and 2 μM for adriamycin. The cell lines were grown in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. The cell suspension, 100 μL, with 5 × 103 cells/well for MCF-7 and A549 and 1 × 104 cells/well for K562 were inoculated into the 96-well plates and cultured under the above conditions for 24 h. The contents of each well was added to 100 μ0 of the testing solutions in triplicate and incubated for 72 h; the final concentration for each extract, compound and adriamycin was 100 μg/mL, 10 μM, and 1 μM, respectively. The RPMI-1640 medium containing 5% FBS was used as the blank control. The MTT solution with the concentration of 5 mg/mL in FBS, 20 μL, was added into each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The medium containing MTT was gently pipetted and each well was added 150 μL DMSO to dissolve the formed formazan crystals. Absorbance was recorded on a Spectra Max Plus plate reader at 570 nm. As for K562 cell line, each well was added 10 μL CCK-8 solution (5 mg/mL) to dye and incubated for 6 h. The solution was directly used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm. The cytotoxicity was represented as the inhibition that was calculated as (ODblank − ODsample)/ODblank × 100%. If the inhibition is more than 50%, the IC50 value that is defined as the concentration of the compound to induce 50% inhibition, was measured by continuous dilution into 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, and 0.312 μM, and then calculated by SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) v19.0 software.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Cui, X. et al. Diversity and function of the Antarctic krill microorganisms from Euphausia superba. Sci. Rep. 6, 36496; doi: 10.1038/srep36496 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the NSFC (Nos 41376148 & 81561148012), from the NSFC- Guangdong Joint Fund for Key Projects (No. U1501221), and from the NSFC-Shandong Joint Fund for Marine Science Research Centers (No. U1406402).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Xiaoqiu Cui conducted all the experiments except for partial compounds structure identification and wrote the paper with the help of Weiming Zhu. Guoliang Zhu performed the structural elucidation of partial compounds. Haishan Liu tested the cytotoxicities of the compounds. Guoliang Jiang provided and identified the Antarctic krill samples. Yi Wang instructed Xiaoqiu Cui to identify the microbial strains. Weiming Zhu designed the study, revised the paper, and is responsible for the funds to support this study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Rosenberg E. & Zilber-Rosenberg I. Symbiosis and development: the hologenome concept. Birth. Defects Res. (Part C) 93, 56–66 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfante P., Visick K. & Ohkuma M. Symbiosis. Env. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 475–478 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. T. et al. Bioactive natural products from the Antarctic and Arctic organisms. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 13, 617–626 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel V. The Antarctic krill: resource and climate indicator, 35 years of German krill research. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 26, 41–46 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Everson I. Krill: Biology, Ecology and Fisheries. Fish Fish. 3, 53–59 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Rakusa-Suszczewski S. Bacteria on the body surface and in the stomach of krill (Euphausia superba Dana) (BIOMASS III). Polish Polar Res. 9, 409–412 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Donachie S. P. & Zdanowski M. K. Potential digestive function of bacteria in krill Euphausia superba stomach. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 14, 129–136 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Denner E. B. M., Mark B., Busse H. J., Turkiewicz M. & Lubitz W. Psychrobacter proteolyticus sp. nov., a psychrotrophic, halotolerant bacterium isolated from the Antarctic krill Euphausia superba Dana, excreting a cold-adapted metalloprotease. System. Appl. Microbiol. 24, 44–53 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. F. et al. Determination of fluoride concentration in Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) using dielectric spectroscopy. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 36, 1557–1562 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. S., Pan J. M., Cheng X. H. & Xia W. Biogeochemistry research of fluoride in Antarctic ocean II. The variation characteristic and concentration cause of fluoride in the cuticle of Antarctic krill. Antarctic Research. 4, 36–41 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Sands M., Nicol S. & McMinn A. Fluoride in Antarctic marine crustaceans. Marine Biology. 132, 591–598 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Soevik T. & Braekkan O. R. Fluoride in Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) and Atlantic krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica). J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 36, 1414–1416 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Andres W. W., Kunstmann M. P. & Mitscher L. A. Isolation and structure of 2, 4- dihydroxy-3, 5, 6-trimethylbenzoic acid from Mortierella ramanniana. Specialia. 23, 703–704 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- Hirota A., Morimitsu Y. & Hojo H. New antioxidative indophenol-reducing phenol compounds isolated from the Mortierella sp. fungus. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 61, 647–650 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Isaka M., Chinthanom P., Veeranondha S., Supothina S. & Luangsa-ard J. J. Novel cyclopropyl diketones and 14-membered macrolides from the soil fungus Hamigera avellanea BCC 17816. Tetrahedron. 64, 11028–11033 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto H., Nakamura E., Okuyama E. & Ishibashi M. Six immunosuppressive features from an ascomycete, Zopfiella longicaudata, found in a creening study monitored by immunomodulatory activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 52, 1005–1008 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H., Tian L., Guo Q. Q. & Zhu W. M. Secalonic acid D; A cytotoxic constituent from marine lichen-derived fungus Gliocladium sp. T3. Arch. Pharm. Res. 29, 59–63 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N. et al. First results on citrinin biomarkers in urines from rural and urban cohorts in Bangladesh. Mycotoxin Res. 31, 9–16 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson M. F. & Damoglou A. P. Conversion of the mycotoxin citrinin into dihydrocitrinone and ochratoxin A by Penicillium viridicatum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 574–578 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Krogh P., Hasselager E. & Friis P. Studies on fungal nephrotoxicity. Acta Path. Microbiol. Scand. Section B. 78, 401–413 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Z. H. et al. Isocoumarin derivatives from the sea squirt-derived fungus Penicillium stoloniferum QY2-10 and the halotolerant fungus Penicillium notatum B-52. Arch. Pharm. Res. 30, 816–819 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nong X. H., Zheng Z. H., Zhang X. Y., Lu X. H. & Qi S. H. Polyketides from a marine-derived fungus Xylariaceae sp. Mar. Drugs. 11, 1718–1727 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark B. R., Capon R. J., Lacey E., Tennant S. & Gill J. H. Citrinin revisited: from monomers to dimers and beyond, Org. Biomol. Chem. 4, 1520–1528 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakana D. et al. New citrinin derivatives isolated from Penicillium citrinum. J. Nat. Med. 60, 279–284 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Clark B., Capon R. J., Lacey E., Tennant S. & Gill J. H. Quinolactacins revisited: from lactams to imide and beyond. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4, 1512–1519 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. B., Aoki T. & Jung T. S. Pathogenesis of and strategies for preventing Edwardsiella tarda infection in fish. Vet. Res. 43, 67 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. D. Vibrio vulnificus in Oceans and health: pathogens in the marine environment (ed. Belkin & Colwell) 253–276 (Springer, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Leotta G. A., Piñeyro P., Serena S. & Vigo G. B. Prevalence of Edwardsiella tarda in Antarctic wildlife. Polar Biol. 32, 809–812 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- George W. et al. Human Infection with Edwardsiella tarda. Ann. Intern. Med. 70, 283–288 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert J. et al. Two cases of severe sepsis due to Vibrio vulnificus wound infection acquired in the Baltic Sea. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 23, 912–915 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub V., Kim A. C. & Krol V. Surgical wound infection, tuboovarian abscess, and sepsis caused by Edwardsiella tarda: case reports and literature review. Infection 38, 487–489 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof W., Ginkel C. J. W., Cohen E. B. & Mekkes J. R. Prospective randomized study comparing debriding effect of krill enzymes and non-enzymatic treatment in venous leg ulcers. Dermatologica 181, 293–297 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N. & Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura G., Suzuki S., Takatsuki A., Ando K. & Arima K. Ascochlorin, a new antibiotic, found by paper-disk agar-diffusion method. I isolation, biological and chemical properties of ascochlorin. J. Antibiot. 9, 539–544 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 65, 55–63 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. F. et al. Five new phorbol esters with cytotoxic and selective anti-inflammatory activities from Croton tiglium. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 1986–1989 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.