Abstract

Relationship stability is a key indicator of well-being, but most U.S.-based research has been limited to different-sex couples. The 2008 panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) provides an untapped data resource to analyze relationship stability of same-sex cohabiting, different-sex cohabiting, and different-sex married couples (n = 5,701). The advantages of the SIPP data include the recent, nationally representative, and longitudinal data collection; a large sample of same-sex cohabitors; respondent and partner socioeconomic characteristics; and identification of a state-level indicator of a policy stating that marriage is between one man and one woman (i.e., DOMA). We tested competing hypotheses about the stability of same-sex versus different-sex cohabiting couples that were guided by incomplete institutionalization, minority stress, relationship investments, and couple homogamy perspectives (predicting that same-sex couples would be less stable) as well as economic resources (predicting that same-sex couples would be more stable). In fact, neither expectation was supported: results indicated that same-sex cohabiting couples typically experience levels of stability that are similar to those of different-sex cohabiting couples. We also found evidence of contextual effects: living in a state with a constitutional ban against same-sex marriage was significantly associated with higher levels of instability for same- and different-sex cohabiting couples. The level of stability in both same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couples is not on par with that of different-sex married couples. The findings contribute to a growing literature on health and well-being of same-sex couples and provide a broader understanding of family life.

Keywords: Union Stability, LGBT, Cohabitation, Marriage

Introduction

The relationship stability of marriage and cohabitation has been studied extensively among different-sex couples (Amato 2010; Manning and Cohen 2012; Teachman 2002). To date, only a handful of studies have examined relationship stability among same-sex couples, with the bulk of this work on European couples (Andersson et al. 2006; Kalmijn et al. 2007; Lau 2012; Ross et al. 2011). In the United States, most recent work has focused on distinctions among legally recognized relationships (marriages or civil unions) (Badgett and Herman 2013; Rosenfeld 2014). Given that not all same sex couples had the legal option to marry until June 26, 2015, it is important to examine relationship stability among same-sex cohabiting couples.

Drawing on recently collected, nationally representative, longitudinal data from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), we extend the limited knowledge about stability in same-sex relationships by evaluating how same-sex relationship stability compares with the stability of different sex cohabitations and marriages in the U.S. context. From the incomplete institutionalization, minority stress, relationship investments, and couple homogamy perspectives, we anticipate that same-sex cohabiting couples are less stable. Alternatively, from an economic resources perspective, we expect that same-sex cohabiting couples are more stable than different-sex cohabiting couples. In addition to testing these competing hypotheses, we also consider the role of social context gauged by residence in a state with a policy declaring marriage to be between one man and one woman. Because relationship stability is a key indicator of well-being among different-sex couples, it is important to understand how same-sex couples fare—particularly in the contemporary context, which is marked by sharp social and legal change (Gates 2013).

Background

Prior research on the stability of same-sex couple relationships rests largely on work in Europe, with only a handful of recent U.S.-based studies. Some of the European studies have contrasted formally recognized same-sex relationships (registered partnerships, civil partnerships, domestic partnerships) and different-sex marriages. Drawing on Swedish and Norwegian population registration data from the mid- to late 1990s, Andersson and colleagues (2006) reported that same-sex couples in registered partnerships have higher instability than their counterparts in different-sex marriages. In 2004, the British government formally recognized civil partnerships in England and Wales. Recent evidence shows that same-sex registered partnerships are more stable than different-sex marriages in these countries (Ross et al. 2011). This difference in stability could be due to early adopters, who were the most stable same-sex couples.

European-based research on cohabiting same-sex relationships has found that same-sex relationships are less stable than different-sex relationships. Kalmijn et al. (2007) analyzed linked tax record data for unions formed in the 1990s in the Netherlands and reported that same-sex couples over age 30 in relationships of at least one year in length experience higher instability within a 10-year window than either different-sex cohabiting or married couples. These are likely not formalized relationships because registered domestic partnerships and legal marriage in the Netherlands were introduced in 1998 2001, respectively (Steenhof and Harmsen 2003). Drawing on two longitudinal birth cohort studies (16- to 34-year-olds 1974 to 2004) in Britain, Lau (2012) showed that cohabiting same-sex couples have higher dissolution rates than different-sex married or cohabiting couples.

Evaluations of the U.S. context are important because the policy and social environments surrounding same-sex relationships in the United States are quite distinct from those in Europe. The paucity of recent research on same-sex relationship stability in the U.S. context reflects the lack appropriate data with sufficient sample sizes of same-sex couples. A few earlier studies have considered stability among same-sex couples; for example Blumstein and Schwartz (1983) and Kurdek (1998, 2004) drew on select convenience samples from the late 1970s and 1980s, respectively, and reported lower stability among same-sex couples.

A few recent studies drew on representative data sets that indicated similar levels of stability among same-sex and different sex-couples in the United States, accounting for legal or formal status of the relationship. Badgett and Herman (2013) used aggregate-level U.S. administrative data and found that among couples in legally recognized unions (domestic partnerships, civil unions, and marriages), dissolution rates are higher among different-sex than same-sex couples. They acknowledged that the stability difference may be partly due to the selection of same-sex couples who enter into formalized relationships as well as the legal complications in the United States surrounding the dissolution of same-sex marriages and partnerships. Rosenfeld (2014) employed longitudinal data from the How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST) data set, which contains an oversample of same-sex couples, and observed stability from the point of relationship (not marriage) initiation. He reported that over a three-year time span starting in 2009, same-sex couples in formalized or marriage-like relationships (n = 137) share similar odds of dissolution as different-sex married couples.

Recent U.S. research focusing on unmarried same-sex couples suggests similar odds of relationship stability for same-sex and different-sex couples depending on gender or residence of the couple. Rosenfeld (2014) reported that in the HCMST sample, unmarried different-sex and same-sex couples (sexual, dating, and cohabiting) (n = 266) share similar dissolution rates. Joyner et al. (2014) drew on a subsample of same-sex couples from the young adult cohort (ages 26–32) of a large nationally representative survey, the National Longitudinal Study Adolescent to Adult Health (n = 277); they found that relationship stability among same-sex and different-sex couples (sexual, dating, cohabiting, and married) depends on the gender and residence of the couple. Young adult female same-sex couples have levels of stability that are comparable to those of different-sex couples, but male same-sex couples have higher levels of relationship instability than different-sex couples (Joyner et al. 2014). Further, the observed stability differences are partly related context, which is measured by the neighborhood concentration of same-sex couples and county-level voting patterns. Same-sex couples in neighborhoods with high concentrations of same-sex couples or living in counties with greater shares of the population voting for a Democratic presidential candidate experience levels of relationship stability on par with different-sex couples (Joyner et al. 2014). These studies all advance our understanding of same-sex couple stability, but no U.S. research has focused on the relationship stability of cohabiting same-sex relationships accounting for the policy climate toward same-sex marriage. It is important to focus on cohabiting same-sex relationships because they constitute about four out of five same-sex residential relationships (Badgett and Herman 2013), and until recently, same-sex marriage was a legal option in only a few states.

Explanations for Relationship

Stability Same-sex couples may experience lower levels of relationship stability because of incomplete institutionalization, minority stress, relationship investments, and couple homogamy. The incomplete institutionalization (Cherlin 1978) and minority stress (Meyer 1995) perspectives on intimate relationships argue that same-sex relationships may be more unstable because of weaker social support and a lack of institutionalization of same-sex relationships. Based on an incomplete institutionalization perspective, we expect greater instability among same-sex than different-sex couples. This hypothesis builds on the incomplete institutionalization framework that Cherlin (1978) introduced to understand stepfamilies and that Nock (1995) extended to study cohabitation. It is well known that cohabiting couples do no not enjoy the same stability as married couples, in part because of the lack of legal and social support. Further, selection processes are operating, with disadvantaged couples less often having sufficient economic resources to marry. Couples may experience stress and conflict as they navigate roles and relationships that lack shared norms and expectations. In addition, consistent with a minority stress approach, same-sex couples may face barriers due to discrimination and challenges to establishing and maintaining high-quality relationships in some communities (Mohr and Daley 2008; Otis et al. 2006). Cohabiting with a member of the same sex may generate stress because it represents a public presentation of a gay or lesbian individual with their partner.

Lower levels of stability may be observed among same-sex couples partly because of sociodemographic indicators, the presence of children, and couple homogamy in terms of age, race, and education. First, children represent a relationship-specific investment that acts as a barrier to dissolution (Levinger 1965), and children tend to deter separation (Brines and Joyner 1999; Kurdek 1998). Yet, relationship-specific capital, including children, is lower among same-sex cohabiting couples (Payne 2014). Further, children in same-sex families are typically the product of a prior different-sex relationship (Goldberg et al. 2014), meaning the same-sex family is akin to a stepfamily. Stepfamily relationships are associated with considerable relationship stress that can undermine relationship stability. Second, homogamy is associated with greater stability among different-sex couples (Bratter and King 2008; Phillips and Sweeney 2006; Teachman 2002). Prior work indicates that homogamy (age, race/ethnicity, education) is lower among same-sex than different-sex couples (Rosenfeld and Kim 2005; Schwartz and Graf 2009).

Alternatively, same-sex cohabiting couples may experience greater stability because they are more advantaged in terms of education, income, and homeownership, and they are less likely to be poor or to receive public assistance (Gates 2009; Krivickas 2010; Williams 2012, 2013) than different-sex cohabitors. We expect that after we adjust for socioeconomic factors, any stability advantage for same-sex cohabiting couples relative to different-sex cohabiting couples may diminish.

Supportive state policy contexts provide some protective buffers for same-sex couples. Gays and lesbians who live in states with supportive policies (employment discrimination and bullying laws) targeted at sexual minorities experience lower levels of serious psychological conditions (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2009). Prior to the U.S. Supreme Court decision to legalize marriage for same-sex couples, some state-level policies forbade the recognition of marriages to same-sex couples: a Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). The absence of a DOMA in a state did not mean that the state was supportive of marriage to same-sex couples, but rather that the state was not actively against marriages to same-sex couples. Although these policies are not associated with the formation or stability of marriages to different-sex couples at the aggregate level (Dillender 2014; Langbein and Yost 2009), no study has assessed this policy indicator and the stability of same-sex or different-sex cohabiting couples. We introduce policy environment for same-sex couple relationships by including an indicator measuring whether the state of residence is one in which DOMA has been enacted by a constitutional amendment that defines marriage as the union of a woman and a man. Prior to 2008, the initial year of this panel of the SIPP, 26 states had enacted such DOMA policies.1

Same-sex couples in cohabiting relationships may experience more stability than their different-sex counterparts because they do not have a marriage option. Same-sex couples with characteristics that support stability are likely to remain cohabiting if they cannot legally marry. At the time of the initial SIPP data collection in 2008, sporadic rulings supported same-sex marriage, but the only states to consistently allow same-sex marriage were Massachusetts (May 2004) and Connecticut (November 2008). Consequently, at the time of the survey, the primary option available to same-sex couples was cohabitation, not legal marriage. Thus, some same-sex couples in cohabiting relationships may have viewed cohabitation as an alternative form of marriage and experienced high levels of stability.

We contrast the stability of same-sex cohabiting couples and different-sex married couples. From a policy perspective, same-sex couples who largely do not have the option to marry may experience a level of stability on par with that of different-sex married couples. Alternatively, the strong legal and social supports for marriage as well as the minority stress perspective lead us to expect that same-sex cohabiting couples are less stable than different-sex married couples. Married different-sex couples and same-sex couples share similar median earnings, with same-sex couples reporting somewhat higher levels of education than their different-sex married counterparts (Gates 2015; Payne 2011; U.S. Census Bureau 2013). Thus, we expect that accounting for economic resources does not explain the stability difference between same-sex cohabiting and different-sex married couples.

Current Study

The present analysis of the 2008 SIPP data provides an opportunity to prospectively study a broad age range (16–87 years old) of same-sex and different-sex couples over a four-year period. We focus on two competing hypotheses. We expect different-sex couples (married and cohabiting) to have greater relationship stability than same-sex cohabiting couples partly because of incomplete institutionalization of cohabitation, minority stress experienced by same-sex couples, fewer relationship investments by same-sex couples, and greater levels of heterogamy among same-sex couples. Alternatively, based on the greater levels of socioeconomic resources in same-sex couples we expect similar or higher levels of stability in same-sex cohabiting than different-sex cohabiting couples. Finally, given the shifting policy climate surrounding same-sex marriage, we test whether a state-level indicator of a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage is associated with lower relationship stability.

Data

We used the 2008 panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP 2008 panel), a longitudinal study the Census Bureau conducted to provide reports on the sources and amounts of income, labor force participation, and welfare program participation and eligibility for the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States. The SIPP 2008 panel included 14 waves that were fielded between 2008 and 2013. At each wave, data about the previous four months were collected, yielding information that spanned 56 continuous months. All members of the household residing at the initial address units were considered original SIPP sample members. These original SIPP sample members were followed over time even if they moved to other places or formed other families. At follow-up waves, data were also collected about people who coresided with original SIPP sample members. Using respondent and partner identification numbers we could track whether couples continuously coresided. Thus, the SIPP provides a unique opportunity to examine how the families of the original SIPP sample members evolve over time. Using the core respondent’s household roster for the first reference month in the panel, we identified 2,283 cohabiting couples (126 same-sex and 2,157 different-sex). By relying on the household roster, we identified only couples in which one partner was the household head; however, this approach had the added benefit that all couples entered the risk period at the same time. We conducted discrete-time event history analyses in which126 same-sex couples contributed 5,175 person-period observations, and the 2,157 different-sex couples contributed 75,369 person-period observations.

We addressed the second research question by including married couples at the time of first interview. To avoid longer duration marriages, we restrict the results in the tables to couples married five or fewer years (3,465 married couples). Sensitivity tests compared these estimates with those for couples marred 10 or fewer years (6,144 married couples), and results were similar across marital duration samples.

Measures

Dependent Variable

We measured union dissolution with two variables: occurrence and timing. We specified the observation window as 2008 to 2013. A couple was coded as intact until one of the partners was not reported on the household roster (based on a partner identification number). The occurrence of dissolution was operationalized as a binary variable coded 0 for couples who had not experienced dissolution (were living together or married) between September 2008 and January 2013, and 1 if they did. Timing was calculated in months, such that respondents were exposed to risk upon entry in the survey and exited the risk period on the date a partner was no longer in the household (for couples who separated before January 2013), were no longer observed in the data (partner dropped out of the study or provided inconsistent reports), or were censored by the end of the date of the last interview.

In supplemental analyses, we focused on respondents who formed unions after the initial SIPP interview in an effort to assess the extent of left-censoring bias (n = 65 same-sex and n = 1,760 different-sex cohabiting couples). We measured duration from the start of the relationship to the point of dissolution or censorship at the time of interview. We report life table relationship stability estimates along with relationship duration according to outcome (stable or unstable). Although these results are not definitive, they provide some insights into assessing whether there could be similar levels of left-censoring bias in our primary analyses for same-sex and different-sex couples.

Focal Characteristics

We measured variables that identify characteristics of the couple and not just one member of the couple. A dummy indicator distinguished same-sex cohabiting couples (1) from different-sex cohabiting couples (0). This measure captures the gender of the members of the couple and their relationship as provided on the roster and not their sexual orientation. Given the small sample size, we could not distinguish female same-sex (n = 65) and male same-sex (n = 61) couples in all models, but we do provide some descriptive findings. The identification of same-sex couples rests on the accurate reporting of gender of the respondent and partner. The SIPP data collection provides some assurances about the accurate reporting of gender because interviews were conducted in-person with a series of interviewer validation checks. This approach is more thorough than surveys relying on respondent’s self-reports.

Two indicators measured age of the couple: a continuous indicator of the younger partner’s age (in years), and a dummy indicator for age heterogamy flagging couples for which the age difference was at least five years (coded as 1).2 Race was coded into three mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories: both partners are white (reference), one partner is nonwhite, and neither partner is white. Small cell sizes for same-sex couples required that we use these indicators of race. Educational attainment was defined as a time-invariant variable that combined both partners’ highest level of education, coded into a three-level dummy indicator: both have a college degree or higher (reference), only one has a college degree or higher, and neither partner has a college degree. Further education refinements would have been preferable, but the sample size prevented detailed categorization of education. A continuous, time-varying indicator for household income was included and logged to adjust for skewness.

We measured the presence of children in the household: couples who lived in a household with at least one minor were coded as 1, and those living in a household without minor children were coded as 0. We recognize that this child may or may not be the offspring of the head and his/her partner. Finally, we created a policy indicator at the state level to measure a context that creates a negative environment for same-sex couples; this indicator DOMA state, flagged couples who lived in a state with a constitutional amendment explicitly banning same-sex marriage as of 2007. In 2007, 26 U.S. states had a DOMA provision passed through a constitutional amendment. This measure taps the social climate for same-sex marriage because constitutional amendments required a voter majority rather than a legislative decision with voter support. We acknowledge that not enacting a DOMA policy does not necessarily signal support for same-sex relationships.

Analytic Strategy

Life table estimates illustrate the relative stability of same-sex and different-sex cohabiting unions. This strategy provides estimates of the timing of instability and accounts for right-censoring. Couples have been together for varying lengths of time, but the SIPP data do not include measures of the duration of the relationship prior to interview. We conducted supplemental analyses of couples who formed relationships during the SIPP period to indirectly assess the potential role of left-censoring.

We estimated discrete-time, binary logistic, event history models at the bivariate and multivariate levels. Model fit statistics suggested that duration dependence is best modeled as a simple continuous function for months. Multivariate models included an indicator denoting same-sex and different sex cohabiting couples, age, race, education, household income, and the presence of minor children. A third model was limited to the gender of the couple and the DOMA state indicator. Finally, the full model included union status, all sociodemographic characteristics, and the DOMA state indicator. The second set of analyses is similar but includes married couples in life table estimates and event history models. We assessed whether variables contribute to model fit by computing the log-likelihood ratio test for nested models.

Results

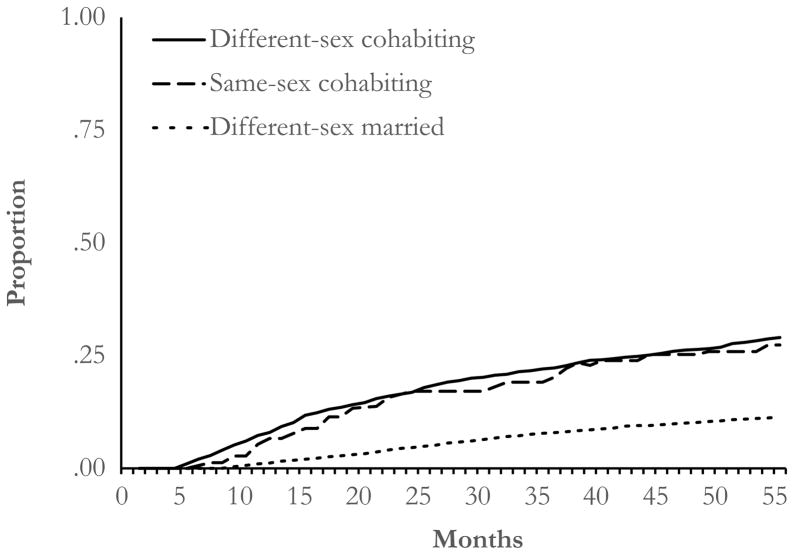

Weighted life table estimates from time of interview to dissolution reveal that 27 % of same-sex couples and 28 % of different-sex cohabiting couples dissolve their relationship (Fig. 1). The time of observation is relatively short: 55 months, or about 4.5 years.3 The cumulative proportion who dissolved their relationship within a 36-month time window (from interview to month 36) is 22 % for different-sex and 20 % for same-sex couples. The dissolution levels for different-sex couples are consistent with reports from similar-aged women in the NSFG at the three-year relationship duration mark (Copen et al. 2013). The average time to dissolution from interview date was 22.8 months for different-sex cohabiting couples and 23.7 months for same-sex couples. Among those who ended their relationship, the median duration was 20 months for both groups.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative proportion of dissolutions among same-sex cohabiting couples and different-sex cohabiting and married couples

We conducted supplemental analyses to assess left-censoring issues by contrasting a subset of same-sex cohabiting couples (n = 65) formed after the initial SIPP interview. Given the short observation period, they were typically observed for two or fewer years (69 %). The cumulative proportion dissolving their relationship at the two-year mark was 33 % among different-sex couples and 40 % among same-sex couples (results not shown). The average time to breakup was 12.4 months for different-sex couples and 10.4 months for same-sex cohabiting couples. The main analyses may be biased toward longer-term relationships, meaning that we are missing disruptions that occur quickly after union formation. It appears that in the first two years of the relationship, same-sex cohabiting relationships dissolve at similar but somewhat higher rates than different-sex couples. We believe this finding is tentative because of the very modest sample size of same-sex couples, but it does align with Rosenfeld’s (2014) analysis showing similar rates of union stability in the early years of unmarried relationships.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couples as well as different-sex married couples. The table denotes significant differences across the relationship types. The SIPP sample of same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couples is similar in terms of age, race, income, and presence of children as reported in American Community Survey (ACS) data (U.S. Census Bureau 2008). Table 1 shows that respondents in same sex-couples had, on average, slightly older partners (age 41) than different-sex cohabiting (age 31) and married (age 33) couples. Same-sex couples were more often heterogamous in their ages (59 %) than different-sex couples cohabiting (39 %) and married (34 %) couples. The racial composition of same-sex couples was less diverse than different-sex couples. Nearly three-quarters (72 %) of same-sex couples were both white, in contrast to 59 % of different-sex cohabiting and 63 % of married couples. Same-sex cohabiting couples had much higher average levels of educational attainment than different-sex couples. Whereas both individuals had at least a college degree in 42 % of same-sex couples, this was true for just 10 % of different-sex cohabiting couples and 23 % of married couples. Same-sex couples reported a significantly higher median household income their first month in the survey compared with their different-sex cohabiting counterparts. Same-sex couples less often had children in their home (23 %) than different-sex cohabiting couples (44 %) and married couples (54 %). Finally, a smaller share of same-sex cohabiting couples (31 %) lived in a state in 2008 that banned marriage to same-sex couples (i.e., DOMA) than did different-sex cohabiting (42 %) and married (44 %) couples. Overall, same-sex cohabiting couples may be more protected against dissolution than are different-sex cohabiting couples because the former possess characteristics associated with lower dissolution, including higher income and education; however, same-sex cohabiting couples may receive less support for their relationships, less often have relationship investments (children), and are less homogamous in terms of age and education.

Table 1.

Couple characteristics, by union type

| Cohabiting Couples | Married Couples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Same-Sex | Different-Sex | Different-Sex | |

| Different-Sex | |||

| Dissolved (%) | 26.8 | 28.2a | 11.3* |

| Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age different-sex | |||

| Younger partner’s age (median) | 41 | 31*a | 33* |

| 5+ years between partners (%) | 58.7 | 39.1*a | 34.3* |

| Race (%) | |||

| Both partners white | 71.9 | 59.2*a | 62.9* |

| One partner nonwhite | 18.2 | 13.8a | 10.6 |

| Neither partner white | 9.9 | 26.9* | 26.5* |

| Education | |||

| Both partners have at least a college degree | 42.3 | 10.3*a | 23.3* |

| One partner has a college degree | 29.0 | 15.7*a | 21.2* |

| Neither partner has a college degree | 28.7 | 74.0*a | 55.5* |

| Monthly Household Income (median) ($) | 7,934 | 4,141*a | 5,609* |

| Minor Child in Household (%) | 23.0% | 44.1*a | 53.6* |

| DOMA State (%) | 31.3 | 41.7* | 44.0* |

| Total(%) | 2.0 | 34.7 | 63.3 |

| N (unweighted) | 126 | 2,157 | 6,144 |

Note: All estimates are weighted with the indicator, WHFNWGT.

Source: 2008 SIPP Core Data File Waves 1–14.

Denotes a significant difference (p < .05) from same-sex couples.

Denotes a difference (p < .05) between different-sex cohabiting and married couples.

Table 2 presents event history logistic regression estimates of the odds ratio of dissolving a same-sex cohabiting relationship. Corresponding with the life table findings we presented, same-sex and different-sex couples experience similar odds of relationship dissolution. The characteristics of different-sex and same-sex couples are included in Model 2. After we account for traditional predictors of relationship stability, same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couples share similar odds of instability. The sociodemographic characteristics operate in a similar way in this model as in bivariate models. Couples who are younger experience higher odds of dissolution, but age heterogamy is not tied to dissolution. Couples with education heterogamy (in which only one in the couple has a college degree) face a modestly higher dissolution risk than when both members of the couple have at least a college degree. Neither income nor presence of a child is associated with dissolution, net of other covariates. The contrast of Model 1 and Model 2 shows that the sociodemographic indicators significantly contributed to model fit. Model 3 includes the measure of same-sex union and the indicator measuring state policy banning same-sex marriages. Couples living in a state with a ban against marriage to same-sex couples experience higher odds of dissolution. Model 4 shows that the policy-level variable is marginally related to relationship stability net of the traditional sociodemographic predictors.4 The log-likelihood test indicates that the DOMA measure contributes to model fit (p = .09).

Table 2.

Odds ratios from logistic regression predicting union dissolution for cohabiting couples

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-Sex Union | 0.89 | 1.04 | 0.90 | 1.05 |

| Younger Partner’s Agea | 0.98** | 0.98** | ||

| Age Heterogamyb | 1.04 | 1.04 | ||

| Race (ref. = both partners white) | ||||

| One partner nonwhite | 0.97 | 0.98 | ||

| Neither partner white | 1.03 | 1.04 | ||

| Education (ref. = both have at least a college degree) | ||||

| One has a college degree | 1.35† | 1.36† | ||

| Neither has a college degree | 1.24 | 1.22 | ||

| Household Income (logged) | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||

| Minor Child in Household | 0.98 | 0.98 | ||

| DOMA Statec | 1.20* | 1.17† | ||

| Month | 0.99† | 0.99 | 0.99† | 0.99 |

| N (observations) | 80,544 | 80,544 | 80,544 | 80,544 |

| N (couples) | 2,283 | 2,283 | 2,283 | 2,283 |

| Model χ2 | 4.27 | 36.16*** | 7.08† | 37.63*** |

Notes: Regression models are weighted with the indicator, WHFNWGT. The model χ2 statistics are likelihood-ratio test statistics rather than goodness-of-fit tests.

In years.

Age heterogamy flags couples having at least a five-year difference between partners’ ages.

DOMA state is an indicator that flags couples living in a state that had a constitutional amendment restricting marriage to one man and one women.

Source: 2008 SIPP Core Data File Waves 1–14.

p < .10;

p <.05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Next, we contrast the relationship stability of same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couples with that of married couples. Figure 1 shows that married couples have much higher levels of stability than cohabiting couples. Fewer than 1 in 10 (7.9 %) married couples had separated within three years of observation, and the cumulative proportion of married couples who eventually dissolved their union was 11.3 %. The mean duration among married couples who ended their relationships was 28.3 months.5

Table 3 presents the multivariate results showing that same-sex cohabiting and different-sex cohabiting couples have a statistically significant higher odds of dissolving their relationships than different-sex married couples at the bivariate level (Model 1). This finding also holds in Model 2, which includes the sociodemographic indicators. Model 2 shows that couples who are younger experience lower odds of dissolution, and age heterogamy is associated with higher odds of dissolution. Nonwhite couples experience higher odds of dissolution. Highly educated married and cohabiting couples (both have at least a college degree) have lower levels of instability. Children are associated with marginally significant lower odds of dissolution. Model 3, which includes the relationship type and the state-level policy measures, shows that cohabiting and married couples living in a state that has banned marriage of same-sex couples experience marginally significant higher odds of dissolution. The policy-level measure does not explain the association between union type (marriage or cohabitation) and dissolution. In the final model (Model 4), the sociodemographic indicators operate similar to those in the earlier models, but the DOMA indicator is no longer statistically significant.6 Further, the DOMA indicator does not significantly contribute to the fit of the model.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from logistic regression predicting union dissolution among married and cohabiting couples

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union Type (ref. = different-sex married) | ||||

| Different-sex cohabiting | 2.86*** | 2.64*** | 2.86*** | 2.65*** |

| Same-sex cohabiting | 2.53*** | 2.82*** | 2.57*** | 2.85*** |

| Younger partner’s agea | 0.98** | 0.99** | ||

| Age heterogamyb | 1.15* | 1.15* | ||

| Race (ref. = both partners white) | ||||

| One partner nonwhite | 1.16 | 1.17 | ||

| Neither partner white | 1.18* | 1.19* | ||

| Education (ref. = both have at least a college degree) | ||||

| One has a college degree | 1.49*** | 1.49*** | ||

| Neither has a college degree | 1.62*** | 1.61*** | ||

| Household Income (logged) | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||

| Minor Child in Household | 0.86† | 0.86† | ||

| DOMA Statec | 1.13† | 1.09 | ||

| Month | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| N (observations) | 234,481 | 234,481 | 234,481 | 234,481 |

| N (couples) | 5,701 | 5,701 | 5,701 | 5,701 |

| Model χ2 | 295.33*** | 369.41 | 297.00*** | 369.82*** |

Notes: Regression models are weighted with the indicator, WHFNWGT. The model χ2 statistics are likelihood-ratio test statistics rather than goodness-of-fit tests.

Source: 2008 SIPP Core Data File Waves 1–14.

In years.

Age heterogamy flags couples having at least five years difference between partners’ ages.

DOMA state is an indicator that flags couples living in a state that did not have a constitutional amendment restricting marriage to one man and one women.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Discussion

In this article, we examined how relationship stability varies for same-sex and different-sex cohabiting and married couples. Stable relationships are linked to high levels of emotional, financial, physical, and social health and well-being. We found that same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couples share similar levels of relationship stability.

Our results belie several perspectives commonly used to explain variation in relationship stability, including incomplete institutionalization, minority stress, relationship investment, couple homogamy, and sociodemographic perspectives. We hypothesized that same-sex couples may experience higher levels of instability relative to their different-sex counterparts partly because same-sex couples less often have children (relationship-specific capital) and tend to be more heterogamous. However, we found no statistical difference in the levels of stability for different-sex versus same-sex cohabiting couples. Also, our findings are not consistent with the hypothesis that same-sex couples may experience higher levels of stability because of their more advantaged sociodemographic standing compared with different-sex cohabiting couples. Perhaps countervailing forces are operating resulting in no difference in stability. Alternatively, the findings from this study may spur researchers to pursue novel theoretical and empirical approaches to study same-sex couple stability by including assessments of variation within same-sex couples. The majority of these potential theoretical explanations are predicated on different-sex relationships and gender-based behavior. New work will need to challenge these presumptions and reconsider issues related to gender dynamics in relationships.

State-level policy targeted at preventing same-sex couples from legally marrying appears to be associated with relationship instability among cohabitors, regardless of gender composition. In other words, cohabiting couples who live in states without constitutional amendments supporting DOMA legislation experience higher levels of stability.7 These findings show that DOMA policy was associated with lower relationship stability for cohabiting couples, which is consistent with prior work that established the importance of context in assessments of stability (Joyner et al. 2014). Yet, DOMA policy is not associated with relationship stability for married couples, which is consistent with aggregate-level analyses showing no association between DOMA policies and different-sex marriage and divorce (Dillender 2014; Langbein and Yost 2009). The DOMA legislation indicator may be a proxy for other contextual variables that are associated with stability. Thus, the policy context appears to play some role in the stability of cohabiting relationships, and attention to other policies related to lesbian and gay protections is warranted. Further, research has shown that same-sex marriage policies may have different effects depending on region or ethnicity (Trandafir 2014), suggesting that variability in the role of policy variables is a promising avenue for future studies.

Although our study provides new insights into relationship stability, it has a few shortcomings. First, because couples were observed after their relationships started, we did not assess stability from the beginning of the union but rather from the point of interview. In our analyses, the cohabiting couples were related to the head of household. For this reason, we cannot determine the extent of left-censoring. Still, our supplemental analyses of unions formed after initial interview showed same-sex cohabiting couples have slightly higher but largely similar levels of instability early on in the relationship, as uncovered by Rosenfeld (2014). This finding is not conclusive but may suggest that different-sex and same-sex couples do not end their relationships at different paces and that left-censoring operates similarly for both types of cohabiting couples. Second, the data include a limited set of predictor variables. Although we had measures about both members of the couple, the SIPP does not include indicators of some key factors found to be tied to relationship stability, such as religiosity or detailed relationship histories that include prior cohabitations. Third, measuring same-sex cohabiting couples in survey data can be challenging. For instance, there could be selection bias associated with who is willing to identify as a same-sex couple in census data (Black et al. 2000), and this willingness may vary by some of the same sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., education, race/ethnicity, and geographic location) on which we compared same-sex and different-sex couples. Separately, analyses of the census and ACS data have identified response error that potentially overestimates same-sex couples resulting from respondents’ having selected the “wrong” gender (see Black et al. 2007; O’Connell and Lofquist 2009; O’Connell et al. 2010). The SIPP data are based on in-person CAPI interviews with several validation checks, providing additional confidence in the reporting of gender of the household members. The inclusion of sexual orientation in surveys would provide a further check on the accuracy of the household roster data. Fourth, most population-based surveys do not have large sample sizes of same-sex cohabiting couples. Small sample sizes raise questions about statistical power, limiting our ability to detect significant differences. However, the small substantive difference suggests that the observed, nonsignificant difference in the share of same-sex versus different-sex couples dissolved is unlikely to be driven by the small sample size; the difference in the share of same-sex versus different-sex couples dissolving would need to exceed 8 % to yield a statistically significant difference. A strategy for future research would be to oversample same-sex couples. Fifth, these analyses do not account for same-sex legal marriages, domestic partnerships, or civil unions. At the time of survey, few states had legalized same-sex marriage, and only a handful of states or cities recognized domestic partnerships or civil unions. Because formal recognition is now mandated for every state, it is important that future work recognize varying forms of formal recognition of same-sex relationships. We acknowledge that the sample size of same-sex couples is not sufficiently large to consider variation according to gender or parenthood status. Sixth, the DOMA indicator is fixed based on residence in 2008. The vast majority (90 %) of the sample did not move to another state, but it may be important to capture mobility in future work. Although this analysis provides a snapshot of a specific period in recent U.S. history, these results show the potential importance of policy climates for relationship stability. Finally, we recognize the contextual variable is not ideal, given that it captures state-level rather than local-level differences in context. Further, this indicator focuses on negative policy climate factors and ignores potentially positive climate elements, such as offering domestic partnerships, anti-bullying legislation, or protections against employment discrimination. Of course, the absence of a DOMA policy does not necessarily signal support for same sex relationships. One way we attempted to account for the state-level effects was to consider multilevel models but exploratory analyses suggested we did not have the statistical power to estimate multilevel models. Future research that permits more-refined contextual analyses may prove a fruitful avenue of research.

Our study contributes to a growing literature on the well-being of same-sex couples and their families. Unlike the patterns observed in many European countries, in the United States, same-sex and different-sex cohabiting unions appear similarly stable. Despite the distinctive demographic profiles of the two groups, their relationship stability does not differ. Not surprisingly, both types of cohabiting unions—same-sex and different-sex unions—are less stable, on average, than different-sex married unions. Future research on same-sex couple stability is essential as the legal and social context supporting same-sex couple relationship continues to change.

Footnotes

DOMA policies existed in some states based on a statutory basis but were not constitutional amendments, meaning they did not require a voter majority to pass and could be more easily overturned. To assess public opinion surrounding same-sex marriages, we focus on DOMA constitutional amendments.

We use the terms “homogamy” and “heterogamy” as they are commonly used in demographic research on cohabitation (Blackwell and Lichter 2004; Schwartz 2010), but we recognize that these terms technically refer to marriage.

Although the sample sizes do not support in-depth analyses of male-male and female-female couples separately, the life tables show higher levels of instability among female (33 %) than male (24 %) same-sex cohabiting couples. This pattern is consistent with some prior work, but these are not conclusive findings. The male-male and female-female couples are similar on all the sociodemographic indicators except presence of children, which is higher among female-female couples.

An interaction of the policy indicator and the same-sex couple measure is not statistically significant, suggesting that the DOMA constitutional amendment is associated with relationship stability in a similar manner for same- and different-sex cohabiting couples. This result should be interpreted with caution given the small sample sizes.

Results are similar when we limit the sample of married couples to those who have been married for fewer than 10 years.

Additional analyses indicate that the DOMA policy indicator is not associated with relationship stability for subsamples of married couples.

Supplemental analyses demonstrated that the interaction term for union type and DOMA was not statistically significant. These results should be considered with caution given small sample sizes.

References

- Amato PR. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:650–666. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Noak T, Seierstad A, Weedon-Fekjaer H. The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography. 2006;43:79–98. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVL, Herman JL. Patterns of relationship recognition by same-sex couples in the United States. In: Baumle AK, editor. International handbook on the demography of sexuality. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. pp. 331–362. [Google Scholar]

- Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L. Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the Unites States: Evidence from available systematic data resources. Demography. 2000;37:139–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L. The measurement of same-sex unmarried partner couples in the 2000 U.S. Census. Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research; 2007. On-Line Working Paper Series, No. CCPR-023-07. Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/72r1q94b. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell DL, Lichter DT. Homogamy among dating, cohabiting, and married couples. Sociological Quarterly. 2004;45:719–737. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein P, Schwartz P. American couples. New York, NY: William Marrow; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bratter JL, King RB. “But will it last?”: Marital instability among interracial and same-sex couples. Family Relations. 2008;57:160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Brines J, Joyner K. The ties that bind: Principles of cohesion in cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Remarriage as an incomplete institution. American journal of Sociology. 1978;84:634–650. [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE, Daniels K, Mosher WD. First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. National Health Statistics Report, No. 64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillender M. The death of marriage? The effects of new forms of legal recognition on marriage rates in the United States. Demography. 2014;51:563–585. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ. Same-sex spouses and unmarried partners in the American Community Survey, 2008 (Report) Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2009. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-ACS2008FullReport-Sept-2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ. Demographics and LGBT health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54:22–23. doi: 10.1177/0022146512474429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ. Demographics of married and unmarried same-sex couples: Analyses of the 2013 American Community Survey (Report) Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2015. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Demographics-Same-Sex-Couples-ACS2013-March-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE, Gartrell NK, Gates G. Research report on LGB-parent families (Report) Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2014. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/lgb-parent-families-july-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Manning WD, Bogle R. Social context and the stability of same-sex and different-sex relationships. Bowling Green, OH: Center for Family and Demographic Research; 2014. 2014 Working Paper Series. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, Loeve A, Manting D. Income dynamics in couples and the dissolution of marriage and cohabitation. Demography. 2007;44:159–179. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivickas KM. FP-10-08 Same-sex couple households in the U.S., 2009. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family and Marriage Research; 2010. Family Profiles, Paper No. 14. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=ncfmr_family_profiles. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Relationship outcomes and their predictors: Longitudinal evidence from heterosexual married, gay cohabiting, and lesbian cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:553–568. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Are gay and lesbian cohabiting couples really different from heterosexual married couples? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:880–900. [Google Scholar]

- Langbein L, Yost MA., Jr Same-sex marriage and negative externalities. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90:292–308. [Google Scholar]

- Lau CQ. The stability of same-sex cohabitation, different-sex cohabitation, and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:973–988. [Google Scholar]

- Levinger G. Marital cohesiveness and dissolution: An integrative review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1965;27:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Cohen JA. Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Daly CA. Sexual minority stress and changes in relationship quality in same-sex couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2008;25:989–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Nock SL. A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 1995;16:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell MT, Lofquist DA. Changes to the American Community Survey between 2007 and 2008 and their potential effect on the estimates of same-sex couple households (Report) 2009 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/samesex/files/changes-to-acs-2007-to-2008.pdf.

- O’Connell MT, Lofquist DA, Simmons T, Lugaila TA. New estimates of same-sex couple households from the American Community Survey. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; Dallas, TX. 2010. Apr, Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam/SS_new-estimates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Otis MD, Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Hamrin R. Stress and relationship quality in same-sex couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2006;23:81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK. U.S. families and households: Economic well-being. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2011. (NCFMR Family Profiles, No. FP-11-01) Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-11-01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK. Demographic profile of same-sex couple households with minor children, 2012. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2014. (NCFMR Family Profiles, No. FP-14-03) Retrieved from http://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-14-03_DemoSSCoupleHH.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, Sweeney MM. Can differential exposure to risk factors explain recent racial and ethnic variation in marital disruption? Social Science Research. 2006;35:409–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ. Couple longevity in the era of same-sex marriage in the U.S. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76:905–918. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ, Kim BS. The independence of young adults and the rise of interracial and same-sex unions. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:541–562. [Google Scholar]

- Ross H, Gask K, Berrington A. Civil partnerships five years on. Population Trends. 2011;145:172–202. doi: 10.1057/pt.2011.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR. Pathways to educational homogamy in marital and cohabiting unions. Demography. 2010;47:735–753. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR, Graf NL. Assortative mating among same-sex and different-sex couples in the United States, 1990–2000. Demographic Research. 2009;21(article 28):843–878. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenhof L, Harmsen C. Same-sex couples in the Netherlands. In: Digoix M, Festy P, editors. Same-sex couples, same-sex partnerships & homosexual marriages. A focus on cross-national differentials. INED; 2004. pp. 233–243. Documents de travail No. 124. Retrieved from https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/19410/124.fr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD. Stability across cohorts in divorce risk factors. Demography. 2002;39:331–351. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trandafir M. The effect of same-sex marriage laws on different-sex marriage: Evidence from the Netherlands. Demography. 2014;51:317–340. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Characteristics of same-sex couple households [Data file] Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2008. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/samesex/data/acs.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Characteristics of same-sex couple households [Data file] Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/samesex/ [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. Child poverty in the United States, 2010. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2012. NCFMR Family Profiles, No. FP-12-17. Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-12-17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. Public assistance participation among U.S. children in poverty, 2010. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2013. NCFMR Family Profiles, No. FP-13-02. Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-02.pdf. [Google Scholar]