Abstract

Aims and objectives

This paper aims to provide an updated comprehensive review of the research‐based evidence related to the transitions of care process for adolescents and young adults with chronic illness/disabilities since 2010.

Background

Transitioning adolescent and young adults with chronic disease and/or disabilities to adult care services is a complex process, which requires coordination and continuity of health care. The quality of the transition process not only impacts on special health care needs of the patients, but also their psychosocial development. Inconsistent evidence was found regarding the process of transitioning adolescent and young adults.

Design

An integrative review was conducted using a five‐stage process: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation.

Methods

A search was carried out using the EBSCOhost, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and AustHealth, from 2010 to 31 October 2014. The key search terms were (adolescent or young adult) AND (chronic disease or long‐term illness/conditions or disability) AND (transition to adult care or continuity of patient care or transfer or transition).

Results

A total of 5719 records were initially identified. After applying the inclusion criteria a final 61 studies were included. Six main categories derived from the data synthesis process are Timing of transition; Perceptions of the transition; Preparation for the transition; Patients’ outcomes post‐transition; Barriers to the transition; and Facilitating factors to the transition. A further 15 subcategories also surfaced.

Conclusions

In the last five years, there has been improvement in health outcomes of adolescent and young adults post‐transition by applying a structured multidisciplinary transition programme, especially for patients with cystic fibrosis and diabetes. However, overall patients’ outcomes after being transited to adult health care services, if recorded, have remained poor both physically and psychosocially. An accurate tracking mechanism needs to be established by stakeholders as a formal channel to monitor patients’ outcomes post‐ transition.

Keywords: adolescents, chronic illness and/or disabilities, integrative review, paediatric to adult care services, transitioning care, young adults

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Evidence of improvement in health outcomes of adolescent and young adults with chronic disease and/or disabilities post‐transition by applying a structured multidisciplinary transition programme, especially for patients with cystic fibrosis and diabetes since 2010.

The identification of ‘readiness to transition’ as a critical element to improve patient outcomes.

The need to establish an accurate tracking mechanism to monitor patients’ outcomes post‐transition.

Introduction

The need to provide transitioning care to adolescents and young adults was first recognised during the 1980s in the USA due to increased numbers of paediatric patients with chronic illnesses/disabilities surviving to adulthood (Blum 1991, Blum et al. 1993). Transitioning patients within and across health care facilities has been gradually conceded as a complex process rather than an event or a single step at a point in time (Department of Health Western Australia 2009, Gilliam et al. 2011, Stewart et al. 2014, Westwood et al. 2014). The transition of care process is, therefore, defined as ‘a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of health care as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care within the same location’ (Coleman & Boult 2003, p. 556). Experiences associated with transitioning adolescent and young adults not only impacts on their special health care needs, but also psychosocial development, including ability to consolidate identity, achieve independence and establish adult relationships (de Silva & Fishman 2014).

There are an estimated 4·5 million (18·4%) of youth aged 12–18 requiring special health care needs in the USA (McManus et al. 2013). Of these, it is reported only 40% of them receive transitional services to adult health care, work, and independence as per established national transition core outcomes (Department of Health Western Australia 2009, McManus et al. 2013). Additional research from the USA suggests delays in the transition of young adults with special care needs, approximately 445,000/year, results in these adults continuing to reside under paediatric health care services (Fortuna et al. 2012). In particular, Collins et al. (2012) and de Beaufort et al. (2010) found patients aged 16–17 years with chronic medical conditions remained predominantly under the care of paediatricians (70% of their visits); while patients aged 17–24 were continuing to be seen by a paediatrician for 16% to 36% of their visits (Heaton et al. 2013, Stewart et al. 2014).

The timing of the transition to the adult care services has always been the centre of debate. Late transition (˃18 years old) can lead to poor patient outcomes mainly due to the late exposure to the adult care settings and lack of independence (van Staa et al. 2011b, Paul et al. 2013). Others argue that early transition could be associated with increased risk of psychosocial issues (Helgeson et al. 2013). The ideal time to transit adolescent and young adult with chronic illnesses/disabilities may not be associated with chronological age, especially with patients who have complex health conditions (O'Sullivan‐Oliveira et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014).

Patients often feel anxious and concerned at the thought of being transited to adult care services. Providing sufficient preparation prior to the transition is, therefore, critical (Fegran et al. 2014, de Montalembert & Guitton 2014). Regardless of this awareness, research suggests many patients were unsure of the process with only 21% of parents/primary carers reporting their child had discussions with the adult health care provider prior to the transition (McManus et al. 2013). Patients also reported that the transition was not carried out systematically due to what they believed was a lack of coordination (Bindels‐de Heus et al. 2013).

Patients have also observed differences between the two care settings during the transition process (de Silva & Fishman 2014). Paediatric health care providers sometimes ignore the growing independence of adolescents. In contrast, adult care providers encourage adolescent patients to take responsibility for their health even though this may lead to neglect of physical, psychological and social development (Valenzuela et al. 2011, Hanna & Woodward 2013, Huang et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014). As a result, adolescents and young adults often feel lost in adult care services leading to lower rates of follow‐up appointments, attendance and medication compliance (van Staa et al. 2011a).

A range of approaches and strategies (Kingsnorth et al. 2007, Crowley et al. 2011), especially structured transitioning programmes, have been developed and implemented to improve patients’ health outcomes (Grant & Pan 2011, Chaudhary et al. 2013). Evidence on the effectiveness of these programmes is not conclusive, which may be due to wide variations in the structure and delivery of those programs (Doug et al. 2011, Hankins et al. 2012).

Aim

This paper aims to provide an updated comprehensive review of the research‐based evidence related to the transitions of the care process for adolescents and young adults with chronic illness/disabilities since 2010. The results of this review will recommend critical elements for developing transition programmes.

Methods

Design

The design is an integrative review, a method of research that appraises, analyses and integrates literature on a topic so that new frameworks and evaluations are generated (Torraco 2005). This methodology allows the inclusion of studies with diverse data collection methods (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). The PRISMA statement was also used, in combination with the integrative review, to structure the review, minimise analysis bias and systematically present findings.

Literature search strategies

This review was conducted to synthesise the research evidence from 2010 to 31 December 2014. Articles eligible for inclusion were those published in English with full‐text access. Eligible studies were peer reviewed, with clear evidence of research methodology, including qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods and systematic reviews.

A search was carried out on the following databases: CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and AustHealth. Database‐specific subject headings and relevant text words were used. Search strategies contained terms related to (adolescent or young adult or adolescent* or teen*) and (chronic disease or long‐term ill* or long‐term condition* or chronic ill* or chronic condition* or disability or disabled children or disabled person) and (transition to adult care or continuity of patient care or transfer* or transition*).

Search outcomes

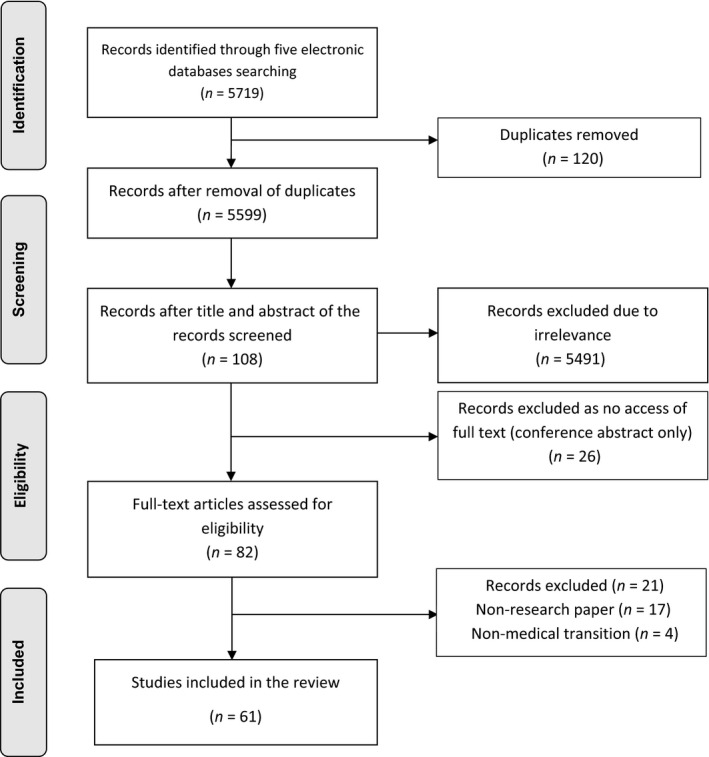

The combined database search generated a total of 5719 records, 120 duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were appraised to confirm those that fitted the review question (n = 5491 excluded). The remaining 108 records were reviewed against selection criteria. A further 47 records were excluded as conference abstracts (26), nonresearch paper (17), and nonmedical transition (4). A hand search of the reference lists was also conducted with no further results. A hand search of the reference lists was also conducted, and no additional studies were identified. A total of 61 studies were included. Figure 1 is a flowchart of the process of the study selection.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the search and study selection process (PRISMA).

Data evaluation

The quality of included articles was appraised independently by the first author (HZ) who has more than 20 years of paediatric nursing experience, and the fourth author (PD), a professor of nursing. Meta‐analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (MAStARI) and Qualitative Assessment Review Instrument (QARI) were used to assess the methodological quality of the 61 studies (The Joanna Briggs Institute 2011). No studies were further excluded on the basis of quality assessment.

Data extraction and synthesis

Item‐by‐item comparison of extracted data enabled coding and grouping, which identified six main categories. All authors validated emerging patterns throughout the analysis process (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). The categories provided the framework to organise the literature and compare the studies systematically (Torraco 2005).

Results

Study demographics

Sixty‐one studies were included (see Table 1), and the majority was conducted in the USA (31), followed by UK (7), Canada (7) and the Netherlands (6). The study designs employed included nonexperimental quantitative studies (35), qualitative design (15), mixed methods design (6), and systematic review (5). Of the 35 quantitative studies, the majority were conducted using survey. Semi‐structured individual interviews and focus group were the primary data collection methods of the qualitative studies. The main focus of the studies included chronic illness/condition in general (24), disabilities (9), and diabetes (5).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 61 included studies

| First author (year) country of origin | Health condition | Study design | Data collection method | Sample | Main results – six categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of transition | Perceptions of the transition | Preparation for the transition | Outcomes post‐ transition | Barriers | Facilitating factors | |||||

|

Blackman (2014) USA |

Cerebral palsy (CP) | Quantitative | Survey | 80 AYACD (15–17 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

de Silva (2014) USA |

Inflammatory bowel disease | Literature review | Search was not reported | 31 articles (1999–2013) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

|

Fernandes (2014) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 155 AYACD (16–25 years) 104 parents | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Huang (2014) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | RCT | 81 AYACD (12–20 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Knapp (2014) The Netherland |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 376 matched pairs of adolescent (≥16) ‐parent | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

McLaughlin (2014) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey |

169 Internists 195 GPs |

✓ | |||||

| O'Sullivan‐Oliveria (2014) USA | Chronic disease | Qualitative | Four focus groups | 28 HCPs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Rutishauser (2014) Switzerland |

Chronic disease | Quantitative cross‐sectional | Survey |

AYACD 283 pre‐transfer 89 post‐transfer |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Shrewsbury (2014) Australia |

Obesity | Systematic review | Search 1982–2012 | Three primary‐documents and 24 2nd documents | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Stewart (2014) Canada |

Disability | Qualitative phenomenological study | Individual and focus group interview | 57 in total 15 AYACD (19–30 years); 16 parents; 25 HCPs; seven researchers | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Thomson (2014) Canada |

Epilepsy | Systematic review | Search 1994–2014 (12–25 years patients) | 54 included studies | ✓ | |||||

|

van Staa (2014) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 518 AYACD (18–25 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Zhang (2014) Australia |

Chronic disease | Literature review | Search was not reported | 31 articles published from 1999–2013 | ✓ | |||||

|

Applebaum (2013) USA |

Rheumatol‐ogy and general | Mixed methods | Survey & focus group | AYACD (13–21 years) 35 survey 20 AYACD +13 parents interview | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Baumann (2013) Switzerland |

Neuro‐disabilities | Quantitative | Chart review | 267 AYACD (16–25 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Bindels‐de Heus (2013) The Netherlands |

Profound intellectual & multiple disabilities | Quantitative | Survey | 131/583 parents of AYACD with PIMD (16–26 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Chaudhary et al. (2013) USA |

Cystic fibrosis | Quantitative | Survey | 91 adult CF AYACD mean age 30·8 ± 9·3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Dickinson (2013) New Zealand |

Juvenile idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) | Qualitative | Focus groups | Eight AYACD with JIA (16–21 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Garvey (2013) USA |

Type 1 diabetes | Quantitative | Survey | 65 Respondents (response rate 32%) mean age 26·6 ± 3·0 | ✓ | |||||

|

Hilderson (2013) Belgium |

JIA | Qualitative | Semi‐structured in‐depth interview | 11 AYACD (18–30 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Hunt (2013) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 179/11,218 Adult‐centered hospitalists responded | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

McManus (2013) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 17,114 parents respondents of AYACD (12–18) | ✓ | |||||

|

Paul (2013) UK |

Mental health | Quantitative | Survey | 154 AYACD mean age 18·1 (SD = 0·8) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Schwartz (2013) USA |

Cancer | Mixed methods | Survey & focus groups |

14 AYACD (16–28 years) Parents (n = 18) HCPs (n = 10) |

✓ | |||||

|

Sonneveld (2013) The Netherlands |

JRA; Type 1 diabetes; neuro‐muscular disorder | Quantitative | Survey | 127 AYACD (12–25); 166 parents; 18 HCPs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Stinson (2014) Canada |

Chronic disease | Systematic review | Search period (1995–2012) | 14 Included studies | ✓ | |||||

|

Swift (2013) UK |

ADHD – mental health | Qualitative | Semi‐structured interview | Parents and 10 ADHD patients aged ≥17 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

van der Toorn (2013) The Netherlands |

Chronic urological condition | Quantitative | Survey | 80 AYACD (mean age 21) seven parents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Collins (2012) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 113 Paediatric HCPs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Fortuna (2012) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | Cross‐sectional data of two national survey – AYACD (22–30 years) delayed transition | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Garvey (2012) USA |

Type 1 diabetes | Quantitative | Survey | 258 (53%) AYACD mean age 19·5 ± 2·9 | ✓ | |||||

|

Godbout (2012) France |

Chronic endocrine conditions | Quantitative | Survey | 73/153 AYACD mean age 24·7 ± 4·5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

|

Hankins (2012) USA |

Sickle cell disease (SCD) | Quantitative | Pre‐post measures | 83 AYACD (17–19 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Helgeson (2012) USA |

Type 1 diabetes | Quantitative | Survey | 118 AYACD mean age 18·05(SD = 0·36) | ✓ | |||||

|

Hovish (2012) UK |

Chronic disease | Mixed methods | Case note review & interview | 11 AYACD (no age provided); six parents; three clinicians in CCS; six Clinicians in ACS | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Pakdeeprom (2012) Thailand |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 100 AYACD (14–20 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Sebastian (2012) UK |

Inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS) | Quantitative | Survey | Gastroenterologists 358/729 (62%) adult & 82/132 (49%) paediatrics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Bhaumik (2011) UK |

Intellectual disability | Mixed methods | Mapping; survey; grounded theory – interview | Mapping/informants from three services; survey – carers of AYACD 79/140 (56%); interview – 24 Carers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

Brewer (2011) USA |

Disabilities | Quantitative | Pre‐post programme | 14,733 AYACD average age: 17·6 | ✓ | |||||

|

Bryant (2011) USA |

Haemo‐globionopathy | Qualitative phenomenological study | Semi‐structured interview | 14 AYACD (19–15 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Croke (2011) USA |

Disabilities | Mixed methods | Survey data; observations; & semi‐structured interview | 403 AYACD (15–18 years); Sample size not reported for qualitative data collection | ✓ | |||||

|

Davies (2011) Canada |

Neurological disorder | Qualitative | In‐depth interview | 17 Parents of 11 AYACD (18–21 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Dowshen (2011) USA |

HIV/AIDS | Review | Search was not reported | Five studies | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Duke (2011) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | National Survey | 18,198 Parents of AYACD (12–17 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Dupuis (2011) Canada |

Cystic fibrosis | Qualitative | Semi‐structured Interview | 26 participants seven families (seven AYACD, seven mums and four dads); Aged 15–18 years; eight HCPs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Gilliam (2011) USA |

HIV | Qualitative | Semi‐structured face‐2‐ face & phone interview | 19 key informants/HCPS from 14 Adolescent Trials Network Clinics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

|

Goossens (2011) Belgium |

Congenital heart disease | Quantitative | Observations & database | 749 Patients with CHD ≥21 in 2009 | ✓ | |||||

|

Huang (2011) USA |

Chronic disease | Qualitative | Focus group | 10 young adults (three IBD; four diabetes; three CF) & 24 HCPs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Kaehne (2011) UK |

Intellectual disabilities | Qualitative | Semi‐structured interview | Three local authorities | ✓ | |||||

|

Kingsnorth (2011) Canada |

Complex disability | Mixed methods | 11 fields notes & focus group | 30 participants for 11 peer support session; eight Parents of AYACD (12–18 years) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Maslow (2011) USA |

Chronic disease (CD) | Quantitative | Data from a national survey |

13,136 non‐CD 829 with CD mean age 28·8 |

✓ | |||||

|

Nishikawa (2011) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Data from a national survey | 18,198 AYACD (12–17 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Park (2011) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Review document and database | Framework and researches; National survey data | ✓ | |||||

|

Price (2011) UK |

Type 1 diabetes | Qualitative | Semi‐structured interview | 11 AYACD & two returned after a year for a 2nd interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Sawicki (2011) USA |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 192 AYACD (16–26 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

Valenzuela (2011) USA |

HIV | Qualitative | Semi‐structured interview | 10 HIV from AYACD (24–29 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

van Staa (2011a) The Netherlands |

Chronic disease | Qualitative | Semi‐structured interview | 24 AYACD after transfer (15–22 years) 24 parents; 17 HCPs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

van Staa (2011b) Netherlands |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 954/3,648 AYACD completed (12–19 years) | ✓ | |||||

|

de Beaufort (2010) Canada |

Diabetes | Quantitative | Survey | 92/578 (16%) of the International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Fredericks (2010) USA |

Liver transplant recipients | Quantitative | Survey | 71 liver transplant recipient (11–20 years) & 58 parents | ✓ | |||||

|

Wong (2010) Hong Kong |

Chronic disease | Quantitative | Survey | 137 AYACD (16–19 years) 67 parents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Six categories emerged from the 61 studies: timing of transition; perceptions of the transition; preparation for the transition; patients’ outcomes post‐transition; barriers to the transition; and facilitating factors to the transition. The data analysis also identified a further 15 subcategories.

Category 1 Timing of transition

The category timing of transition (12/61 included studies) consisted of three subcategories: timing to educate patients about transition process; the preferred timing to transit; and the age transited.

Three studies explored the preferred timing to begin the education of paediatric patients with chronic illnesses/disabilities about the transition process. Two studies suggested the most appropriate time is early teens (11–12 years) or time of the diagnosis (10–14 years) (Price et al. 2011, de Silva & Fishman 2014); whereas Sebastian et al. (2012) argued 14 years or later.

Nine studies investigated the preferred timing of being transited to adult care services. Eight studies suggest that preferred timing relates to chronological age (mid teen – early twenties) (de Beaufort et al. 2010, Dowshen & D'Angelo 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, Godbout et al. 2012, Sebastian et al. 2012, Fernandes et al. 2014, Rutishauser et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014). Others are of the view that the timing of transit should not rely on chronological age, but be based on the level of maturity and responsibilities of each patient (Gilliam et al. 2011, O'Sullivan‐Oliveira et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014).

Five studies examined the age of patient transited to adult care services. Of the five studies, four indicated that transition occurred between the ages of 18, or after graduating from high school, to 19 years (Huang et al. 2011, Garvey et al. 2012, Godbout et al. 2012, Sebastian et al. 2012). The remaining study reported greater delays with patients in their early twenties (Fortuna et al. 2012).

Category 2 Perceptions of the transitions

Twenty‐eight included studies investigated the perceptions of patients, parents and health care providers towards the transition process.

From patients’ perspective, 13 studies examined their pre‐transition perceptions. Patients expressed negative feelings towards the idea of transition. They felt anxious about the thought of the upcoming transition (Valenzuela et al. 2011, Chaudhary et al. 2013, Rutishauser et al. 2014, Thomson et al. 2014) or were unwilling to be transited (Bryant et al. 2011) because they were uncertain or concerned about the process (Bryant et al. 2011, Godbout et al. 2012, Applebaum et al. 2013, Swift et al. 2013, de Silva & Fishman 2014). In particular, patients were worried if they would be accepted by the adult care services (Swift et al. 2013, Stewart et al. 2014). However, in three other studies, patients verbalised they were ready and keen to transit (Wong et al. 2010, van Staa et al. 2011b, Dickinson & Blamires 2013).

Patients, after transit to the adult care services, acknowledged challenges and considerable differences between the two health care services with regard to environment and care delivery (Price et al. 2011, Valenzuela et al. 2011, Hilderson et al. 2013, Huang et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014, Van Staa & Sattoe 2014). In general, some patients felt satisfied with the transition process (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Price et al. 2011, Godbout et al. 2012, Chaudhary et al. 2013, Sonneveld et al. 2013) and considered the transition as an opportunity for individual growth (van Staa et al. 2011a, Valenzuela et al. 2011). Other patients were less satisfied with the transition process, and they even felt pushed into the adult care service (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Bryant et al. 2011, de Silva & Fishman 2014) without sufficient preparation (Blackman & Conaway 2014, Van Staa & Sattoe 2014).

For parents/carers, leaving paediatric care services was more challenging than for patients (van Staa et al. 2011a). Prior to the transition, parents/primary carers indicated concerns about the process (Kingsnorth et al. 2011, Swift et al. 2013). They also felt stressed about the future, and this was over and above the ongoing suffering of living with their child (Dupuis et al. 2011, Kingsnorth et al. 2011). Parents were also worried about being labelled as over‐advocating or being ‘difficult’ in the transition process. Only limited evidence revealed positive feelings of the parents towards the transition and this related to their awareness of the transition plan (Wong et al. 2010, Knapp et al. 2014).

Only one study explored parental perceptions on their child's transition process. Parents expressed their feeling of being abandoned and lost during the transition process. They were also fearful in navigating adult care services (Davies et al. 2011).

In terms of how health care providers perceived the transition process variations were evident between paediatric and adult services. Adult health care providers considered paediatric service providers were over protective; whereas adult health care providers were perceived as uncaring towards the adolescent and young adult patients by paediatric health care providers (de Silva & Fishman 2014). Also, 40% of adult health care providers felt uncomfortable caring for the young adult patients (Hunt & Sharma 2013). Further half of them were unwilling or not keen to accept the young adult patients (McLaughlin et al. 2014).

Category 3 Preparation for the transition

It has been recognised that preparing the adolescent and young adult patients for transition impacts significantly on patients outcomes post‐transition (Bindels‐de Heus et al. 2013, Dickinson & Blamires 2013). It is essential, therefore, to assess the patients’ readiness for the transit. However, no single assessment tool/instrument has been widely accepted as the most reliable tool (de Silva & Fishman 2014).

A systematic review conducted by (Stinson et al. 2014) focused on the transition readiness assessment instruments/tools and concluded that the tools from the eight included studies were neither reliable nor valid, including Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ). In a more recent review, ten transition readiness assessment tools were examined with a focus on the psychometric properties of the tool. The review argued that TRAQ demonstrated adequate content validity, construct validity, and internal consistency. As a result TRAQ was recommended as the best‐validated tool to assess the adolescents and young adults’ readiness for the transition (Zhang et al. 2014).

In other research, Schwartz et al. (2013) identified that the Social‐Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness to Transition (SMART) proved to be a valid tool. The reliability was supported by other studies that examined the four‐specific components disease‐related knowledge (Fredericks et al. 2010, van der Toorn et al. 2013), skills/self‐efficacy (Fredericks et al. 2010, Sawicki et al. 2011, van Staa et al. 2011b, Applebaum et al. 2013, van der Toorn et al. 2013), relationships/communication (van der Toorn et al. 2013), and psychosocial/emotions (Fredericks et al. 2010). The SMART measured the patients’ beliefs/expectations, developmental maturity (patient only), goals/motivation to determine if the patients are ready to be transferred to the adult care service (Schwartz et al. 2013).

Additional characteristics also identified as impacting the quality of the preparation process include gender (Fredericks et al. 2010, Sawicki et al. 2011, McManus et al. 2013), age (Fredericks et al. 2010, Sawicki et al. 2011, McManus et al. 2013, Knapp et al. 2014), ethnicity group (McManus et al. 2013), family annual income (McManus et al. 2013), severity of the illness (Sawicki et al. 2011, McManus et al. 2013), level of psychosocial support (Pakdeeprom et al. 2012), patients’ attitude towards transition (van Staa et al. 2011b, Pakdeeprom et al. 2012), source and type of paediatric care (Duke & Scal 2011), and health insurance access (Fortuna et al. 2012, McManus et al. 2013).

Category 4 Patients’ outcomes post‐transition

Five included studies evaluated the effectiveness of transition programmes. In general, patients valued the structure and guidance offered by the programmes, especially those that assisted patients to gain independence socially and physically (Chaudhary et al. 2013, Huang et al. 2014), to comply with adult clinic visits (Hankins et al. 2012), and to engage in career development activities (Brewer et al. 2011, Croke & Thompson 2011). Patients also appreciated being informed about drugs and alcohol prevention and meeting adult health care providers prior to transition (Price et al. 2011). However, regardless of the implemented available transition programmes, patients’ anxiety levels towards the transition did not alter (Chaudhary et al. 2013).

Sixteen studies measured the outcomes of the patients who had not been involved in a structured transition program. There was no systematic evaluation of the outcomes mainly due to the lack of tracking mechanisms for transferred patients (Gilliam et al. 2011). The transition record was often incomplete, so the total number of reported transitions was based on estimation (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011). Patients articulated that the care they received post‐transition was inconsistent and of a less standard compared to the paediatric setting (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Goossens et al. 2011, Park et al. 2011, van Staa et al. 2011a, Helgeson et al. 2012, Paul et al. 2013, Sonneveld et al. 2013). This was evidenced by poor medication adherence (van Staa et al. 2011a, de Silva & Fishman 2014) and low clinic attendance or even cessation of follow‐up appointments (Goossens et al. 2011, van Staa et al. 2011a, Helgeson et al. 2012, de Silva & Fishman 2014). Also, two studies examined the social outcomes of patients compared to those without chronic health conditions. Patients with chronic illnesses/disabilities experienced poor educational and vocational opportunities with low graduating rates from college and lower incomes (Maslow et al. 2011, Baumann et al. 2013).

Despite the lack of structured transition programmes, four studies reported positive patient outcomes a year or more after being transited. These included general satisfaction with care provision (Dickinson & Blamires 2013), treatment (Godbout et al. 2012) and advice on their future life (Nishikawa et al. 2011). One study also reported that patients had similar rates of marriage and having children as when compared to those without childhood illness (Maslow et al. 2011).

Category 5 Barriers to the transition

Five major barriers were identified as impacting the transition process. The first barrier related to inadequate preparation prior to transition. Patients reported not being referred to a specific adult HCP (Garvey et al. 2013), not receiving information from an adult HCP (Wong et al. 2010, Kaehne 2011, Garvey et al. 2012, Paul et al. 2013, Rutishauser et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014), not being offered a visit prior to transition to the adult care service (Garvey et al. 2012, Hilderson et al. 2013), and poor communication between the health care providers (Wong et al. 2010, Kaehne 2011, Garvey et al. 2012, de Silva & Fishman 2014). Patients also reported a lack of satisfaction with the transition process due to unavailability of structured written‐plans (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, Kaehne 2011, van Staa et al. 2011a, Shrewsbury et al. 2014) and the lack of coordination of the process (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Davies et al. 2011, Huang et al. 2011, Kaehne 2011, Paul et al. 2013, Sonneveld et al. 2013).

Ability to access and use adult care services was considered as the second major barrier. Issues include lack of resources (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Davies et al. 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, Huang et al. 2011, Collins et al. 2012, Godbout et al. 2012, Sebastian et al. 2012, Paul et al. 2013, O'Sullivan‐Oliveira et al. 2014, Stewart et al. 2014), limited availability of the clinicians’ time (Bhaumik et al. 2011, Collins et al. 2012, Sebastian et al. 2012), limited health insurance coverage (Dowshen & D'Angelo 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, Huang et al. 2011), long waiting lists (Hovish et al. 2012), and lack of a tracking mechanism after patients are transited (Gilliam et al. 2011). Inconsistencies in the provision of care to patients were also considered as a limitation. This was seen as resulting from the different model of care delivered in the adult care setting as compared to the paediatric setting (Huang et al. 2011, Garvey et al. 2012, 2013, Hovish et al. 2012). Specifically, insufficient communication, especially handing over patients’ information from paediatric to adult health service providers were identified (Dowshen & D'Angelo 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, Huang et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014, Stewart et al. 2014).

Complex health conditions posed the third barrier to the transition process. The transition was impacted according to health service providers by patients’ impaired cognitive development and mental health issues (Davies et al. 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, van der Toorn et al. 2013). Other issues included patients’ negative attitude towards the transition (Wong et al. 2010, Gilliam et al. 2011, Rutishauser et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014), difficulties leaving a familiar environment (Dowshen & D'Angelo 2011, van der Toorn et al. 2013, Fernandes et al. 2014, O'Sullivan‐Oliveira et al. 2014, Rutishauser et al. 2014), insufficient knowledge and self‐management skills (Gilliam et al. 2011, Sonneveld et al. 2013, de Silva & Fishman 2014) and especially poor medication and follow‐up adherence (Gilliam et al. 2011, van der Toorn et al. 2013).

Excessive parental involvement in the care of patients was perceived as the fourth barrier to the transition by both nurses and physicians (Huang et al. 2011, de Silva & Fishman 2014). This was evidenced by parents’ negative attitude towards adult care services (Wong et al. 2010, O'Sullivan‐Oliveira et al. 2014), over controlling of their child (Huang et al. 2011, Sonneveld et al. 2013, de Silva & Fishman 2014), and over‐reliance on the paediatrician (Bindels‐de Heus et al. 2013, van der Toorn et al. 2013, Fernandes et al. 2014, de Silva & Fishman 2014).

The final barrier involves the inability of some paediatric health care providers to relinquish care of the patient (Dowshen & D'Angelo 2011, de Silva & Fishman 2014). Paediatric health care providers found it difficult to hand over patients to the adult care services due to long‐established rapport with patients and their families (Gilliam et al. 2011, O'Sullivan‐Oliveira et al. 2014). In contrast, adult health care providers faced challenges relating to nonfamiliarity with the treatment and clinical parameters of the patients (Dupuis et al. 2011, Huang et al. 2011, Hunt & Sharma 2013, Stewart et al. 2014).

Category 6 Facilitating factors to the transition

Nine included studies explored factors that enable the transition process. Facilitating factors include preparation prior to transit (Wong et al. 2010, Hovish et al. 2012), a structured written plan/program to guide the transition process (Gilliam et al. 2011, Hovish et al. 2012, Sebastian et al. 2012), a key health care provider from paediatric care services to coordinate the transition process (Collins et al. 2012, Hovish et al. 2012), the quality of health care providers and relationship built‐up with the patients (Wong et al. 2010, Swift et al. 2013), parents acting as a facilitator (Davies et al. 2011, Kingsnorth et al. 2011, van der Toorn et al. 2013), and patients’ self‐management skills (Wong et al. 2010, de Silva & Fishman 2014).

Discussion

We conducted this integrative review to synthesise the research evidence from 2010–2014 on transitions of care for the adolescents and young adults with chronic illnesses/disabilities. This integrative review adds to the body of knowledge of 16 previous review papers published ≤2010 (Refers to Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 16 previously published review articles

| First author (year) country of origin | Health condition | Study design | Search period | Included studies | Main results – six categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of transition | Perceptions of the transition | Preparation for the transition | Outcomes post‐transition | Barriers | Facilitating factors | |||||

|

Fegran (2014) Denmark |

Chronic disease | Qualitative meta‐synthesis | 1999 –November 2010 | 18 studies | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Hanna (2013) USA |

Diabetes | Systematic review meta‐analysis | Not reported | 23 studies published from 1992–2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

Bloom (2012) USA |

Chronic disease | Literature review | 1986–2010 | 15 studies | ✓ | |||||

|

de Jongh (2012) UK |

Chronic disease | Systematic review meta‐analysis | 1993–2009 | Four RCTs included | ✓ | |||||

|

Crowley (2011) UK |

Chronic disease | Literature review | 1998–2010 | 10 studies | ✓ | |||||

|

Doug (2011) UK |

Palliative care | Literature review | 1995‐February 2008 | 92 studies | ✓ | |||||

|

Grant (2011) Canada |

Chronic disease | Content analysis | Not reported | Five transition models | ✓ | |||||

|

Lindsay (2011) Canada |

Chronic disease | Integrative review | 2000 – August 2010 | 34 studies | ✓ | |||||

|

Lugasi (2011) Canada |

Chronic disease | Meta‐summary review | 1994–2009 | 46 studies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

Watson (2011) UK |

Complex healthcare needs | Scoping review | Not reported | 19 studies published from 1990–2010 | ✓ | |||||

| First author (year) country of origin | Health condition | Study design | Search period | Included studies | Main results – eight categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of transition | Perceptions of the transition | Preparation for the transition | Outcomes post‐transition | Barriers | Facilitating factors | |||||

|

Lotstein (2010) USA |

Chronic disease | Literature review | Not reported | 33 studies published from 1990–2010 | ✓ | |||||

|

Rapley (2010) Australia |

Chronic disease | Integrative review | Not reported | 74 Studies published from 1989–2008 | ✓ | |||||

|

Wang (2010) USA |

Chronic disease | Literature review – an ecological approach | 1999–2008 | 46 studies | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Jalkut (2009) USA | Congenital heart disease | Literature review | 1950–2008 | 28 studies | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

|

Kingsnorth (2007) Canada |

Physical disabilities | Systematic review | 1985–2006 | Six studies | ✓ | |||||

|

While (2004) UK |

Chronic disease | Literature review | 1981–2001 | 126 studies | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

Congruent evidence was found in this review that patients should be made aware they will need to transition to adult services. The ideal timing to transit patients to adult care services broadly ranged from the late teens to the early twenties. It was argued that patients should be transited according to their developmental stage and self‐management abilities, which is similar to three prior review papers (While et al. 2004, Jalkut & Allen 2009, Fegran et al. 2014). In reality, however, patients were mostly transited in their late teens, especially at the ‘iconic’ age of high school graduation (Watson et al. 2011, Hanna & Woodward 2013).

The majority of patients in this review expressed negative feelings towards transition, which was consistent with four previous review papers (Jalkut & Allen 2009, Wang et al. 2010, Hanna & Woodward 2013, Fegran et al. 2014). Some patients were even apprehensive about their future when surrounded by older and sicker patients (Lugasi et al. 2011). Consistent evidence from this and a previous review (Lugasi et al. 2011) suggests that parents/carers felt reluctant towards the transition with general concern expressed about the process and feelings of abandonment. Health care providers with adolescent care experience considered the transition as part of their routine practice while others with only adult care experience felt uncomfortable to care for adolescent and young adults. Paediatric health care providers, however, displayed a lack of trust in adult health care providers by being unwilling to hand over care of the patients (Jalkut & Allen 2009).

Evidence from this review indicates there has been an increased effort to prepare patients prior to transition by assessing readiness, which was not formally recognised in any of the previous review papers. However, inconclusive evidence was found on the effectiveness of transition readiness assessment tool.

This review compared to the seven previous reviews found that most ‘programs’ identified in the literature were approaches or services, and not formally structured transition programs. The main content of the approaches or services from previous reviews included (1) introduction of transition coordinator; (2) self‐management skill training; (3) flexibility of adult clinic service delivery; and (4) assessment of readiness (Kingsnorth et al. 2007, Crowley et al. 2011, de Jongh et al. 2012, Hanna & Woodward 2013). It was noticed that most approaches/services developed were for specific health conditions, i.e., cystic fibrosis (Doug et al. 2011), diabetes (Crowley et al. 2011, Hanna & Woodward 2013), and physical disabilities (Kingsnorth et al. 2007) rather than for more generic use. Four studies argued that patients with health conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, severe intellectual disability and obesity, received very little attention when transitioning from paediatric to adult health services (Dowshen & D'Angelo 2011, Gilliam et al. 2011, Maslow et al. 2011, Shrewsbury et al. 2014).

Also, Grant and Pan (2011) analysed five structured transitioning programmes for the young adult population with chronic illnesses/disabilities. Overall, the appraised intervention/services and programmes were found to be useful, especially for diabetic patients trying to maintain glycosylated haemoglobin levels (Crowley et al. 2011, Hanna & Woodward 2013). However, the validation and sustainability of most of the intervention and programs were questioned (Kingsnorth et al. 2007, Doug et al. 2011, Grant & Pan 2011, Watson et al. 2011, de Jongh et al. 2012, Hanna & Woodward 2013). There is limited evidence on developing and implementing transitioning programmes for young adults with complex health needs, such as cerebral palsy and autism (Watson et al. 2011).

The review also found poor patients’ outcomes both clinically and psychosocially after being transited without structured transition programmes, which was supported by two previous review papers (Lugasi et al. 2011, Bloom et al. 2012, Hanna & Woodward 2013). Some patients articulated that they were treated like adults being part of decision‐making and taking more control of their health conditions (Lugasi et al. 2011).

Both this review and five previous reviews agreed on five major barriers hindering the transition process, including lack of planned transition process, insufficient preparations, poor health care service accessibility, ineffective communication between health care services and a negative attitude by patients towards the transition process (Jalkut & Allen 2009, Lotstein et al. 2010, Wang et al. 2010, Lindsay et al. 2011, Lugasi et al. 2011).

Facilitating factors associated with a smooth transitioning process were identified by four earlier review studies and were consistent with the outcomes of this review. Patients and their carers appreciated gradual preparation following a structured transition programme, consistency of care, high quality of adult health care providers, parental support, and the patients taking responsibilities of their own health (While et al. 2004, Rapley & Davidson 2010, Lugasi et al. 2011).

The limitation of this integrative review is associated with the search strategy which might have excluded relevant non‐English research studies. The main weakness of the included studies in this integrative review was the lack of objective data resulting from compromises made to research design. More than half of the included studies (32/61) was nonexperimental self‐report surveys. Only two out of 15 included qualitative studies specified the methodology and underlining philosophy being employed – phenomenological theory.

An integrated, rigorous research approach including both quantitative and qualitative methods to examine effectiveness of the transition programme is urgently recommended. Due to inconclusive evidence, further validation of the two identified transition readiness assessment tools (SMART vs. TRAQ) is needed. Most importantly, inconsistent outcomes measures need to be addressed to improve the quality of patients’ transitioning experience.

Conclusion

In the last five years, there has been improved health outcomes for adolescents and young adults with chronic illnesses/disabilities post‐transition through the use of a structured multidisciplinary transition programme, especially for patients with cystic fibrosis and diabetes. However, overall patient outcomes following the transit, if recorded, have remained poor both physically and psychosocially. Active preparation for transitioning paediatric patients with ongoing special health care needs should commence in their early teens. Parents/primary carers, paediatric health care providers, and the receiving adult health care providers also needed to be included in the preparation. Patients’ readiness for transition needs to be accurately and regularly assessed by applying validated measurement tools. The priority for stakeholders and health care providers for both paediatric and adult services is to develop a standardised and evidence‐based transition program, which must be user‐friendly to all patients rather than condition specific. The information with regard to patients’ diagnosis, investigation, management plan, and family/social background is required to be communicated and shared by the health care providers. Training programs also need to be organised for adult health care providers to improve their medical knowledge and communication skills. This review also strongly recommends the need for accurate tracking mechanism to be established by health care services to monitor patients’ outcomes post‐transition, which will ultimately improve the transitioning care for adolescents and young adults with chronic illnesses/disabilities.

Contributions

Study design: HZ & PD; Data collection and analysis: HZ, PD, PR & SD; and manuscript preparation: HZ, PR, PD & SD.

Funding

Australian Research Council ‐ ARC Linkage Grant (Project ID: LP140100563). Nursing and Midwifery Office, WA Department of Health ‐ The Academic Research Grant.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Ms Marta Rossignoli, Librarian of Child & Adolescent Health Service, WA, for her assistance in the literature search.

References

- Applebaum MA, Lawson EF & von Scheven E (2013) Perception of transition readiness and preferences for use of technology in transition programs: teens’ ideas for the future. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 25, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, Newman CJ & Diserens K (2013) Challenge of transition in the socio‐professional insertion of youngsters with neurodisabilities. Developmental Neurorehabilitation 16, 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beaufort C, Jarosz‐Chobot P, de Bart J & Deja G (2010) Transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care: smooth or slippery. Pediatric Diabetes 11, 24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik S, Watson J, Barrett M, Raju B, Burton T & Forte J (2011) Transition for teenagers with intellectual disability: carers’ perspectives. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 8, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bindels‐de Heus KGCB, van Staa A, van Vliet I, Ewals FVPM & Hilberink SR (2013) Transferring young people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities from pediatric to adult medical care: parents’ experiences and recommendations. Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities 51, 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman J & Conaway M (2014) Adolescents with cerebral palsy: status and needs in the transition to adult health services. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 56, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SR, Kuhlthau K, Cleave JV, Knapp AA, Newacheck P & Perrin JM (2012) Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. Journal of Adolescent Health 51, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW (1991) Overview of transition issues for youth with disabilities. Pediatrician 18, 101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, Jorissen TW, Okinow NA, Orr DP & Slap GB (1993) Transition from child‐centered to adult health‐care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health 14, 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer D, Erickson W, Karpur A, Unger D, Sukyeong P & Malzer V (2011) Evaluation of a multi‐site transition to adulthood program for youth with disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation 77, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant R, Young A, Cesario S & Binder B (2011) Transition of chronically ill youth to adult health care: experience of youth with hemoglobinopathy. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 25, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary SR, Keaton M & Nasr SZ (2013) Evaluation of a cystic fibrosis transition program from pediatric to adult care. Pediatric Pulmonology 48, 658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA & Boult C (2003) Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51, 556–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SW, Reiss J & Saidi A (2012) Transition of care: what is the pediatric hospitalist's role? An exploratory survey of current attitudes. Journal of Hospital Medicine 7, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croke EE & Thompson AB (2011) Person centered planning in a transition program for Bronx youth with disabilities. Children & Youth Services Review 33, 810–819. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K & McKee M (2011) Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood 96, 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies HN, Rennick J & Majnemer A (2011) Transition from pediatric to adult health care for young adults with neurological disorders: parental perspectives. Canadian Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 33, 32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Western Australia (2009) Paediatric chronic disease transition framework Health Networks Branch, Department of Health Western Australia, Perth, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AR & Blamires J (2013) Moving on: the experience of young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis transferring from paediatric to adult services. Neonatal, Paediatric & Child Health Nursing 16, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Doug M, Williams J, Paul MA, Kelly D, Petchey R & Carter YH (2011) Transition to adult services for children and young people with palliative care needs: a systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood 96, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N & D'Angelo L (2011) Health care transition for youth living with HIV/AIDS. Pediatrics 128, 762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NN & Scal PB (2011) Adult care transitioning for adolescents with special health care needs: a pivotal role for family centered care. Maternal & Child Health Journal 15, 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis F, Duhamel F & Gendron S (2011) Transitioning care of an adolescent with cystic fibrosis: development of systemic hypothesis between parents, adolescents, and health care professionals. Journal of Family Nursing 17, 291–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegran L, Hall EO, Uhrenfeldt L, Aagaard H & Ludvigsen MS (2014) Adolescents’ and young adults’ transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: a qualitative metasynthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51, 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes SM, O'Sullivan‐Oliveira J, Landzberg MJ, Khairy P, Melvin P, Sawicki GS, Ziniel S, Kenney LB, Garvey KC, Sobota A, O'Brien R, Nigrovic PA, Sharma N & Fishman LN (2014) Transition and transfer of adolescents and young adults with pediatric onset chronic disease: the patient and parent perspective. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine 7, 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna RJ, Halterman JS, Pulcino T & Robbins BW (2012) Delayed transition of care: a national study of visits to pediatricians by young adults. Academic Pediatrics 12, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks E, Dore‐Stites D, Well A, Magee J, Freed GL, Shieck V & Lopez M (2010) Assessment of transition readiness skills and adherence in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatric Transplantation 14, 944–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey K, Wolpert HA, Rhodes E, Laffel LM, Kleinman K, Beste M, Wolfsdorf J & Finkelstein J (2012) Health care transition in patients with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 35, 1716–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey K, Finkelstein EA, Laffel LM, Ochoa JG, Wolfsdorf J & Rhodes C (2013) Transition experiences and health care utilization among young adults with type 1 diabetes. Patient Preference and Adherence 7, 761–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam PP, Ellen JM, Leonard L, Kinsman S, Jevitt CM & Straub DM (2011) Transition of adolescents with HIV to adult care: characteristics and current practices of the adolescent trials network for HIV/AIDS interventions. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 22, 283–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout A, Tejedor I, Malivoir S, Polak M & Touraine P (2012) Transition from pediatric to adult healthcare: assessment of specific needs of patients with chronic endocrine conditions. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 78, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens E, Hilderson D, Gewillig M, Budts W, Van Deyk K & Moons P (2011) Transfer of adolescents with congenital heart disease from pediatric cardiology to adult health care: an analysis of transfer destinations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 57, 2368–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant C & Pan J (2011) A comparison of five transition programmes for youth with chronic illness in Canada. Child: Care, Health and Development 37, 815–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins JS, Osarogiagbon R, Adams‐Graves P, McHugh L, Steele V, Smeltzer MP & Anderson SM (2012) A transition pilot program for adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 26, e45–e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna HM & Woodward J (2013) The transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care services. Clinical Nurse Specialist 27, 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton PA, Routley C & Paul SP (2013) Caring for young adults on a paediatric ward. British Journal of Nursing 22, 1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds K, Snyder P, Palladino D, Becker D & Siminerio L (2012) Characterizing the transition from paediatric to adult care among emerging adults with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 30, 610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds K, Snyder P, Palladino D, Becker D & Siminerio L (2013) Characterizing the transition from paediatric to adult care among emerging adults with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 30, 610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilderson D, Eyckmans L, Van der Elst K, Westhovens R, Wouters C & Moons P (2013) Transfer from paediatric rheumatology to the adult rheumatology setting: experiences and expectations of young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clinical Rheumatology 32, 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovish K, Weaver T, Islam Z, Paul M & Singh SP (2012) Transition experiences of mental health service users, parents, and professionals in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 35, 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JS, Gottschalk M, Pian M, Dillon L, Barajas D & Bartholomew LK (2011) Transition to adult care: systematic assessment of adolescents with chronic illnesses and their medical teams. Journal of Pediatrics 159, 994–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JS, Terrones L, Tompane T, Dillon L, Pian M, Gottschalk M, Norman GJ & Bartholomew LK (2014) Preparing adolescents with chronic disease for transition to adult care: a technology program. Pediatrics 133, e1639–e1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S & Sharma N (2013) Pediatric to adult‐care transitions in childhood‐onset chronic disease: hospitalist perspectives. Journal of Hospital Medicine 8, 627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalkut M & Allen P (2009) Transition from pediatric to adult health care for adolescents with congenital heart disease: a review of the literature and clinical implications. Pediatric Nursing 35, 381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jongh T, Gurol‐Urganci I, Vodopivec‐Jamsek V, Car J & Atun R (2012) Mobile phone messaging for facilitating self‐management of long‐term illnesses Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 12. Art. No.:CD007459. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007459.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaehne A (2011) Transition from children and adolescent to adult mental health services for young people with intellectual disabilities: a scoping study of service organisation problems. Advances in Mental Health & Intellectual Disabilities 5, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsnorth S, Healy H & Macarthur C (2007) Preparing for adulthood: a systematic review of life skill programs for youth with physical disabilities. Journal of Adolescent Health 41, 323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsnorth S, Gall C, Beayni S & Rigby P (2011) Parents as transition experts? Qualitative findings from a pilot parent‐led peer support group. Child: Care Health and Development 37, 833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp C, Huang I, Hinojosa M, Baker K & Sloyer P (2014) Assessing the congruence of transition preparedness as reported by parents and their adolescents with special health care needs. Maternal Children Health Journal 17, 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Kingsnorth S & Hamdani Y (2011) Barriers and facilitators of chronic illness self‐management among adolescents: a review and future directions. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness 3, 186–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lotstein D, Kuo AA, Strickland B & Tait F (2010) The transition to adult health care for youth with special health care needs: do racial and ethnic disparities exist? Pediatrics 126, S129–S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugasi T, Achille M & Stevenson M (2011) Patients’ perspective on factors that facilitate transition from child‐centered to adult‐centered health care: a theory integrated metasummary of quantitative and qualitative studies. Journal of Adolescent Health 48, 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow G, Haydon A, McRee A, Ford C & Halpern C (2011) Growing up with a chronic illness: social success, educational/vocational distress. Journal of Adolescent Health 49, 206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin SE, Machan J, Fournier P, Chang T, Even K & Sadof M (2014) Transition of adolescents with chronic health conditions to adult primary care: factors associated with physician acceptance. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine 7, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MA, Pollack LR, Cooley WC, McAllister JW, Lotstein D, Strickland B & Mann MY (2013) Current status of transition preparation among youth with special needs in the United States. Pediatrics 131, 1090–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montalembert M, Guitton C & French Reference Centre for Sickle Cell Disease (2014) Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 164, 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa BR, Daaleman TP & Nageswaran S (2011) Association of provider scope of practice with successful transition for youth with special health care needs. Journal of Adolescent Health 48, 209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan‐Oliveira J, Fernandes SM, Borges LF & Fishman LN (2014) Transition of pediatric patients to adult care: an analysis of provider perceptions across discipline and role. Pediatric Nursing 40, 113–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakdeeprom B, In‐iw S, Chintanadilok N, Wichiencharoen K & Manaboriboon B (2012) Promoting factors for transition readiness of adolescent chronic illnesses: experiences in Thailand. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 95, 1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Adams S & Irwin CE Jr (2011) Health care services and the transition to young adulthood: challenges and opportunities. Academic Pediatrics 11, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Ford T, Kramer T, Islam Z, Harley K & Singh S (2013) Transfers and transitions between child and adult mental health services. The British Journal of Psychiatry 202, s36–s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C, Corbett S, Lewis‐Barned N, Morgan J, Oliver LE & Dovey‐Pearce G (2011) Implementing a transition pathway in diabetes: a qualitative study of the experiences and suggestions of young people with diabetes. Child: Care, Health and Development 37, 852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapley P & Davidson PM (2010) Enough of the problem: a review of time for health care transition solutions for young adults with a chronic illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing 19, 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser C, Sawyer SM & Ambresin AE (2014) Transition of young people with chronic conditions: a cross‐sectional study of patient perceptions before and after transfer from pediatric to adult health care. European Journal of Pediatrics 173, 1067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki GS, Lukens‐Bull K, Yin X, Demars N, Huang IC, Livingood W, Reiss J & Wood D (2011) Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ – Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 36, 160–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L, Brumley LD, Tuchman L, Barakat L, Hobbie W, Ginsberg J, Daniel L, Kazak A, Bevans K & Deatrick J (2013) Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness for transition to adult care. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics 167, 939–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian S, Jenkins H, McCartney S, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Croft N, Russell R & Lindsay J (2012) The requirements and barriers to successful transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: differing perceptions from a survey of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists. Journal of Crohn's & Colitis 6, 830–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrewsbury VA, Baur LA, Nguyen B & Steinbeck KS (2014) Transition to adult care in adolescent obesity: a systematic review and why it is a neglected topic. International Journal of Obesity 38, 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva PSA & Fishman LN (2014) Transition of the patient with IBD from pediatric to adult care‐an assessment of current evidence. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 20, 1458–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneveld HM, Strating MH, van Staa A & Nieboer AP (2013) Gaps in transitional care: what are the perceptions of adolescents, parents and providers?. Child: Care, Health and Development 39, 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staa A, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J & Latour JM (2011a) Crossing the transition chasm: experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child: Care, Health and Development 37, 821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staa A, van der Stege H, Jedeloo S, Moll HA & Hilberink S (2011b) Readiness to transfer to adult care of adolescents with chronic conditions: exploration of associated factors. Journal of Adolescent Health 48, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D, Law M, Young NL, Forhan M, Healy H, Burke‐Gaffney J & Freeman M (2014) Complexities during transitions to adulthood for youth with disabilities: person‐environment interactions. Disability & Health Journal 36, 1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, White M, Gill N, Colbourne G, Sigurdson S, Duffy KW, Tucker L, Stringer E, Hazel B, Hochman J, Reiss J & Kaufman M (2014) A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift KD, Hall CL, Marimuttu V, Redstone L, Sayal K & Hollis C (2013) Transition to adult mental health services for young people with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a qualitative analysis of their experiences. BioMed Central Psychiatry 13, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (2011) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2011 Edition. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson L, Fayed N, Sedarous F & Ronen GM (2014) Life quality and health in adolescents and emerging adults with epilepsy during the years of transition: a scoping review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 56, 421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Toorn M, Cobussen‐Boekhorst H, Kwak K, D'Hauwers K, de Gier RP, Feitz WF & Kortmann BB (2013) Needs of children with a chronic bladder in preparation for transfer to adult care. Journal of Pediatric Urology 9, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torraco RJ (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela J, Buchanan C, Redcliffe J, Ambrose C, Hawkins L, Tanney M & Rudy B (2011) Transition to adult services among behaviorally infected adolescents with HIV: a qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 36, 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Staa A & Sattoe JNT (2014) Young adults’ experiences and satisfaction with the transfer of care. Journal of Adolescent Health 55, 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, McGrath BB & Watts C (2010) Health care transition among youth with disabilities or special health care needs: an ecological approach. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 25, 505–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R, Parr J, Joyce C, May C & Le Coeur S (2011) Models of transitional care for young people with complex health needs: a scoping review. Child: Care Health and Development 6, 780–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood A, Langerak N & Fieggen G (2014) Transition from child‐ to adult‐orientated care for children with long‐term health conditions: a process, not an event. South African Medical Journal 104, 310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- While A, Forbes A, Ullman R, Lewis S, Mathes L & Griffiths P (2004) Good practices that address continuity during transition from child to adult care: synthesis of the evidence. Child: Care Health and Development 30, 439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R & Knafl K (2005) The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52, 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LHL, Chan FWK, Wong FYY, Wong ELY, Huen KF, Yeoh E‐K & Fok T‐F (2010) Transition care for adolescents and families with chronic illnesses. Journal of Adolescent Health 47, 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LF, Ho JS & Kennedy SE (2014) A systematic review of the psychometric properties of transition readiness assessment tools in adolescents with chronic disease. BioMed Central Pediatrics 14, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]