Abstract

Episodic future thinking, which refers to the use of prospective imagery to concretely imagine oneself in future scenarios, has been shown to reduce delay discounting (enhance self-control). A parallel approach, in which prospective imagery is used to concretely imagine other’s scenarios, may similarly reduce social discounting (i.e., enhance altruism). In study 1, participants engaged in episodic thinking about the self or others, in a repeated-measures design, while completing a social discounting task. Reductions in social discounting were observed as a function of episodic thinking about others, though an interaction with order was also observed. Using an independent-measures design in study 2, the effect of episodic thinking about others was replicated. Study 3 addressed a limitation of studies 1 and 2, the possibility that simply thinking about others decreased social discounting. Capitalizing on Construal Level Theory, which specifies that social distance and time in the future are both dimensions of a common psychological distance, we hypothesized that episodic future thinking should also decrease social discounting. Participants engaged in episodic future thinking or episodic present thinking, in a repeated-measures design, while completing a social discounting task. The pattern of results was similar to study 1, providing support for the notion that episodic thinking about psychologically distant outcomes (for others or in the future) reduces social discounting. Application of similar episodic thinking approaches may enhance altruism.

Keywords: altruism, social discounting, prospection, construal level theory, theory-of-mind

Egoistic theories of altruism posit that some degree of self-interest exists in all altruistic behavior; for example, Hamilton’s (1964a; b) theory of inclusive fitness proposes that altruistic behavior is due to a desire to ensure the survival of one’s genes. More recently, Rachlin (2002) has proposed that an altruist integrates the values of delayed, positive outcomes that result from a series of altruistic acts in a society governed by norms of reciprocity. Rachlin posits that the altruist delays (small) immediate gratification associated with selfish acts for (large) delayed gratification associated with altruistic acts. In other words, altruism is a form of self-control (other prominent scientists have also explored the conceptual and practical similarities between self-control and altruism; Ainslie, 1992; Boyer, 2008; Read, 2001).

Informed by the literature on delay discounting as a measure of self-control, Rachlin and Jones (2008) developed a binary choice procedure that ostensibly measures altruism by quantifying the rate at which an individual discounts a reward for others. This assessment of social discounting refers to the reduction in the subjective value of an outcome for another individual as a function of the social distance, where a high rate of social discounting indicates that rewards quickly lose value as social distance increases (diminished altruism), while a low rate of social discounting indicates that rewards maintain value as social distance increases (enhanced altruism).

Recent research on social discounting as an index of altruism indicates predicted relations with relevant real-world behaviors. Adolescent boys who exhibit aggression and bullying have exaggerated preference for outcomes for the self (compared to those without behavior problems; Sharp et al., 2012), resulting in high rates of social discounting. Also, pregnant women who continue smoking during pregnancy (resulting in potential health consequences to the baby) have higher rates of social discounting than women who quit upon discovering their pregnancy (Bradstreet et al, 2012).

Given these relations, approaches to reduce social discounting may have a positive impact on engagement in altruistic behaviors. Though established approaches to reducing social discounting are limited, the extensive literature on approaches to enhance self-control can inform approaches to enhance altruism. For the purpose of the present research, we consider the evidence on episodic future thinking (see reviews in Atance & O’Neill, 2001; Schacter, Addis, & Buckner, 2008). Episodic future thinking refers to the use of prospective imagery to concretely imagine oneself in future scenarios, and a developing body of evidence indicates that engagement in episodic future thinking reduces delay discounting (Daniel, Stanton, & Epstein, 2013a; 2013b; Lin & Epstein, 2014; Peters & Buchel, 2010). Applied to altruism, the use of prospective imagery to concretely imagine oneself in the scenarios of others could reduce social discounting. Indeed, previous research indicates that episodic simulations can enhance behaviors associated with altruism (Turner, & Crisp, 2010; Turner et al., 2007; see review in Gaesser, 2013). However, this body of research typically involves the impact of situation-specific simulations on intentions of behavior in those situations; for example, Gaesser and Schacter (2014) examined whether imagining helping someone in need increased intention to help that person. The first study reported here examined whether concrete, situation-independent imagery of another individual, rather than imagining altruistic behaviors one might exhibit towards that individual, increased altruism.

Study 1

The first study is a conceptual replication of the research examining episodic future thinking on delay discounting, applied to social discounting. Across two sessions, participants engaged in episodic thinking about others (experimental condition) or themselves (control condition) while completing a social discounting task.

Method

Participants

Fifty undergraduate psychology students at the University of Maryland enrolled in the study for course credit. The recruitment target was informed by previous work (e.g., Peters & Büchel, 2010) as well as our ongoing work examining the effect of similar construal manipulations on delay discounting. Approximately half of the participants were randomized to experience the experimental condition first, with the remaining participants experiencing the control condition first. Data from five participants were excluded due to the following reasons: participant failed to follow instructions (three), research staff error (one), or data violated Johnson & Bickel’s (2008) guidelines for systematic discounting (one). One participant provided usable data for only one (control) condition, and data in that condition was retained. Forty-four remaining participants provided complete datasets.

Materials

Participants were given the following instructions, necessary for completion of the social discounting and episodic thinking tasks:

The following experiment asks you to imagine that you have made a list of the 100 people closest to you in the world ranging from your dearest friend or relative at position #1 to a mere acquaintance at #100. The person at number one would be someone you know well and is your closest friend or relative. The person at #100 might be someone you recognize and encounter but perhaps you may not even know their name.

You do not have to physically create the list – just imagine that you have done so.

Social Discounting task

A computerized, titrating binary choice social discounting task, informed by Rachlin and Jones (2008) and using the algorithm of Du and colleagues (Du, Green, & Myerson, 2002), was administered to determine the subjective values of hypothetical money to be given to someone else at the following social distances: rank order of 1, 10, 20, and 100. In each trial, two outcomes were presented on the screen: $100 for the “other” and a smaller amount for the self. The alternative for the self was titrated across six trials to determine the subjective values (i.e., indifference points) at each specific social distance. On the first of six trials at each social distance, the amount for the self was $50. If the amount for the other was selected, the amount for the self was increased on the subsequent trial to $75; if the amount for the self was selected, this amount was decreased to $25. Over the remaining trials at each social distance, the amount for the self was increased or decreased in this manner, by half of the previous adjustment (e.g., 12.5% increase/decrease for trial 3). The indifference point (i.e., the present subjective value of the amount for the other) was calculated as the amount for the self following the sixth trial.

Before the start of the trials associated with each social distance, a block of episodic thinking questions was administered, using the same social distance qualifier (in the experimental condition only). The different “others,” representing different social distances, were presented in increasing order.

Episodic Thinking conditions

Experimental condition

Participants completed four blocks of paper-and-pencil episodic thinking questions, designed to prime episodic, concrete thinking about another person. Each block was comprised of five fill-in-the-blank questions regarding specific events/activities (having lunch, visiting a website, engaging in a leisurely activity, and completing a task) of an “other”, rank ordered according to subjective closeness, at each of the following social distances: 1, 10, 20, 100. Some example questions were “What did/will this person have for lunch today?”, “Where did/will this person have lunch today?”, and “What did/will this person drink at lunch today?” The person (social distance) qualifiers coincided with the same social distances used in the social discounting task.

Control condition

Participants completed four blocks of questions as in the experimental condition, with the exception that questions were regarding activities of the self (e.g., “What did/will you have for lunch today?”, “Where did/will you have lunch today?”, and “What did/will you drink at lunch today?”). The questions were identical to the experimental condition, with the exception of the person qualifier (self rather than other). See Appendix A for all episodic thinking questions in both experimental and control conditions.

Procedure

In a repeated-measures design, participants completed two 30-minute laboratory sessions separated by one week. Order was counterbalanced, such that half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive the sessions in the experimental-control order and half in the control-experimental order. In each session, the four blocks of episodic thinking questions were interweaved with the four social distances of the social discounting task. For example, in the experimental condition, a block of five episodic thinking questions about person #1 was followed by assessment of social discounting for person #1; in the control condition, a block of five episodic thinking questions about the self was followed by assessment of social discounting for person #1. During each session, participants completed either the experimental or control episodic thinking manipulation, along with the computerized social discounting task. All measures and manipulations are fully reported here.

Analytic Plan

Manipulation Check

To ensure that participants were able to engage in episodic thinking, two raters blind to condition and hypothesis coded each response from both episodic thinking manipulations on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (completely abstract) to 7 (completely concrete). Correlations between raters were positive and significant in both experimental (r[41] = 0.39, 95% CI: (0.09, 0.62]) and control (r[41] = 0.67, 95% CI: (0.46, 0.86)) conditions. Overall mean concreteness ratings were calculated for each condition by taking the mean of the raters’ individual means within condition. Given the good inter-rater reliability, the concreteness ratings from the two raters were averaged for each discounting task completed. Overall, participants answered questions concretely, with high mean concreteness ratings in both experimental and control conditions (5.72, s=.42 vs. 5.81, s=.33, difference=0.09, 95% CI: (−0.06, 0.23)).

Social Discounting

Nonlinear regression was used to obtain estimated social discounting parameters for each participant under each condition, based on Rachlin and Ranieri’s (1992) hyperbolic function: Vd = V / (1+sN), where Vd is the discounted value of an outcome, V is the undiscounted value, N is social distance rank, and s is the measure of social discounting. Low values of s indicate a shallow rate of social discounting (slow loss of value resulting from social distance, i.e., enhanced altruism). Social discounting rates (s) were natural logarithm transformed, ln(s), in order to normalize the distribution. These transformed social discount rates were analyzed using a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with episodic thinking condition (experimental: others vs. control: self) as a within-individual factor, order (experimental-control vs. control-experimental) as an among-individual condition, and their interaction. An exchangeable (a.k.a. compound symmetric) covariance structure was used to model the within-individual covariance. Effect sizes (η2G) were computed as in Olejnik and Algina (2003). These analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT® software, Version 9.4.

Results

Table 1 summarizes participant demographics, which were not associated with social discounting and not included in the main analysis. Table 2 reports social discounting descriptive statistics. Goodness-of-fit of the hyperbolic discounting model to the data was assessed with R2 and root mean squared error (RMSE). R2 is a biased goodness-of-fit measure frequently reported in delay discounting and social discounting literature, and though not appropriate for nonlinear regressions (Johnson & Bickel, 2008), it is reported here for consistency with the established literature (X̄R2= .73, SDR2 = .32). RMSE was X̄RMSE = .108, SDRMSE = .067. Rates of social discounting from the two conditions were positively correlated (Pearson’s r[44]=0.64; 95% CI: (0.42, 0.79)).

Table 1.

Demographic Variables (Frequencies/Means) For All Studies.

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 N = 45 |

Study 2 N = 275 |

Study 3 N = 46 |

|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 (17.8%) | 113 (41.1%) | 13 (28.3%) |

| Female | 37 (82.2%) | 159 (57.8%) | 32 (69.6%) |

| Not Reported | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.1%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Age | |||

| M (SD) | 18.8 (1.1) | 35.6 (12.1) | 19.8 (2.6) |

| (Min, Max) | (18, 22) | (19, 78) | (18, 29) |

| Race | |||

| White/Caucasian | 24 (53.3%) | 205 (74.5%) | 24 (52.2%) |

| Black/African American | 8 (17.8%) | 22 (8.0%) | 7 (15.0%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (11.1%) | 12 (4.4%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Asian/Southeast Asian | 7 (15.6)% | 24 (8.7%) | 13 (28.3%) |

| Native American/American | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Indian | |||

| Other | 1 (2.2%) | 8 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not Reported | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (2.2%) |

Table 2.

Social Discount Rates (Means/Standard Deviations) For All Studies.

| Study | Order | Condition | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Self-Other | Self | 23 | −1.99 | 2.21 |

| Other | 22 | −3.01 | 2.30 | ||

| Other-Self | Self | 22 | −3.15 | 2.18 | |

| Other | 22 | −2.84 | 2.57 | ||

| 2 | NA | Self | 144 | −0.85 | 2.17 |

| Other | 131 | −1.58 | 2.40 | ||

| 3 | Present-Future | Present | 23 | −1.89 | 1.89 |

| Future | 22 | −2.50 | 2.10 | ||

| Future-Present | Present | 22 | −2.06 | 2.82 | |

| Future | 23 | −1.99 | 2.91 |

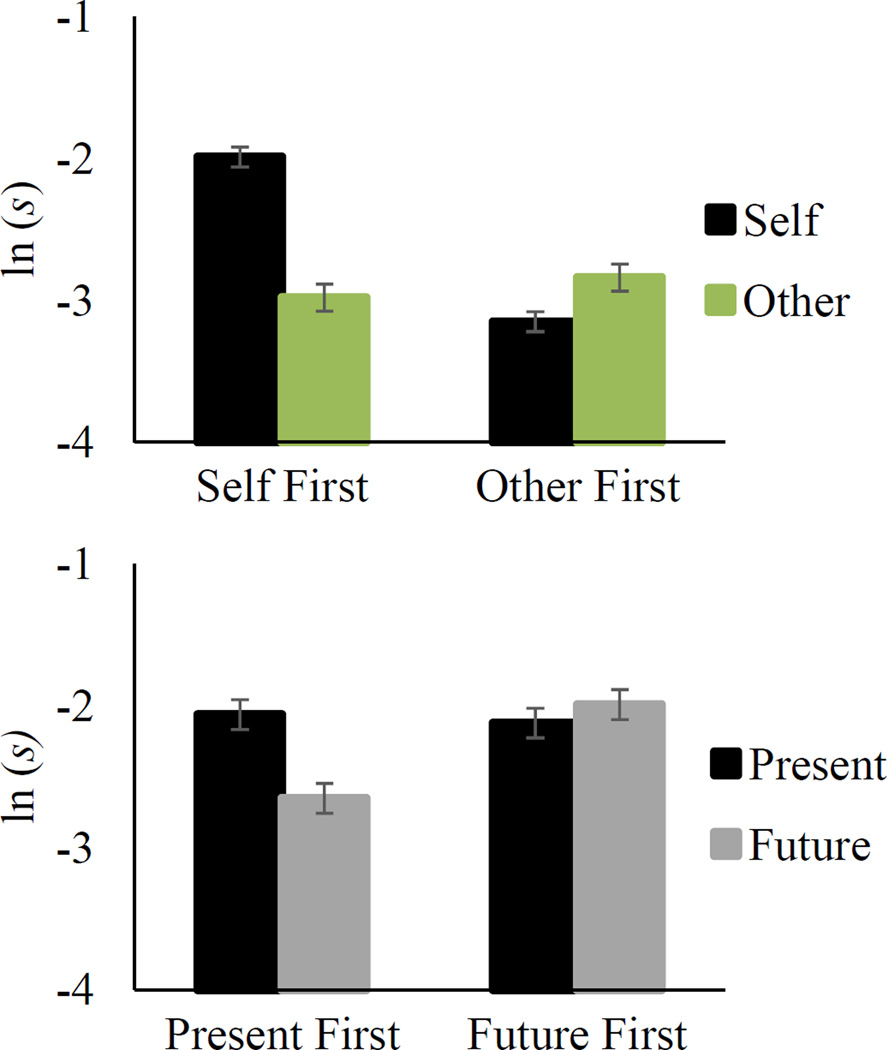

A 2×2 ANOVA examined the effects of condition, order, and their interaction. This ANOVA revealed a significant interaction (F[1,42]=5.23, p=.027), with no significant main effects (both p>0.22; Figure 1, top panel). Comparing by condition within those who experienced the control-experimental sequence revealed a significantly lower rate of social discounting (1.01) in the experimental condition (95% CI: (0.19, 1.83), t[42]=2.49, p=0.017, η2G = .129). However, for those in the experimental-control sequence, a nonsignificantly higher rate of social discounting (0.31) was observed in the experimental condition (95% CI: (−0.52, 1.13), t[42]=0.75, p=0.46, η2G =.013).

Figure 1.

Mean log-transformed social discount rates and standard error of the mean for control (black bars) and experimental (gray bars) conditions in study 1 (top) and study 3 (bottom).

Discussion

The present study examined the effect of episodic thinking about others, compared to episodic thinking about the self, on a measure of altruism: social discounting. The a priori hypothesis, that social discounting would be reduced following episodic thinking about others, was partially supported. The predicted difference was observed only when participants were first exposed to the control condition followed by exposure to the experimental condition; no similar effect was observed when participants were first exposed to the experimental condition followed by exposure to the control condition.

This interaction of episodic thinking and order of exposure is not wholly unexpected. Indeed, the counterbalancing of order was specifically to address this possibility. Unfortunately, because previous literature using repeated-measures in episodic future thinking (e.g., Gaesser & Schacter, 2014) cannot directly address the duration of shifts resulting from an episodic thinking manipulation, we cannot be certain what aspect of the non-independence of observations across the experimental and control conditions resulted in this interaction. However, we believe the most likely explanation for this pattern of results is a carryover effect of the experimental (episodic future thinking of others) condition.

For the order in which the expected effect was observed (control-experimental), the initial exposure to the control condition (episodic thinking of the self) essentially constitutes an absence of a manipulation, as self- and present-bias are the default functioning for most people (Malkoc, Zauberman, & Bettman, 2010). Thus exposure to episodic thinking of others in the second session constitutes a shift away from default functioning, resulting in a change in social discounting. In contrast, for the order in which the expected effect was not observed (experimental-control), the initial exposure to the experimental condition would result in a change in social discounting. A carryover effect of this shift could then impact social discounting in the second session, despite the manipulation intended to restore default functioning in that session. Malkoc and Zauberman observed a similar “lingering effect of mental representation” (2006, p. 620) on time horizon (associated with delay discounting) and note that a form of blocking (Kamin, 1969; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972) could explain such a phenomenon. In proposing this explanation for the order effect, we do not believe it is likely that a session 1 experimental manipulation maintained its effect during the one-week wait until session 2. Rather, we hypothesize that the unique physical environment of the experimental context served as a discriminative stimulus for the experimental episodic thinking manipulations of the present study. Independent of this possibility, the significant interaction of episodic thinking and order in the present study highlights the significance of the relative timing of episodic thinking of others and how such thinking would result in increased altruism.

Study 2

To clarify the presence of the effect of the experimental versus control conditions observed in study 1, without the presence of the order effect, an independent-group design study comparing these conditions was conducted. In order to enhance generalization, participants in study 2 were recruited nationally using online procedures.

Method

Participants

Three hundred and thirty nine (339) Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers were recruited and enrolled. Amazon MTurk is an online marketplace where individuals can complete tasks in exchange for monetary compensation. The substantially larger enrolled sample relative to study 1 was intended to counterbalance the likely reduction in statistical power in this independent-group design study using a slightly abbreviated social discounting procedure, and the potential for relatively elevated error variance resulting from the MTurk sample. Participants were at least 18 years of age and from the Unites States. All participants received $0.25 for completing this 5–10 minute study, as well as being entered into a raffle with a 1% chance to receive a bonus of $10. Data from 64 participants were excluded due to the following reasons: participant failed to follow instructions (42), participants provided fewer than 2 interpretable data points (11), or data violated Johnson & Bickel’s (2008) first guideline for systematic discounting (11). Data from the remaining 275 participants were included in the analyses.

Materials

The direction given to participants to complete the social discounting and episodic thinking tasks were identical to study 1. The abbreviated social discounting task used one fewer social distance than that of study 1, with the Episodic Thinking conditions concurrently using one fewer block of questions. The binary choice procedure was non-titrating.

Social Discounting task

A computerized and abbreviated version of the fixed-trial, binary choice, social discounting task of Rachlin and Jones (2008) was administered to determine the subjective values of hypothetical money to be given to someone else at the following social distances: rank order of 1, 20, and 100. In each trial, two outcomes were presented on the screen: $100 for the “other” and an amount for the self ($25, $50, $75, $100) presented in increasing order for approximately half of the participants and decreasing order for the remaining participants (randomized). The different “others,” representing different social distances, were presented in increasing order.

Episodic Thinking conditions

Experimental condition

Participants completed three blocks of episodic thinking questions, designed to prime episodic, concrete thinking about another person. Each block was comprised of five fill-in-the-blank questions regarding specific events/activities (having lunch, visiting a website, engaging in a leisurely activity,) of an “other”, rank ordered according to subjective closeness, at each of the following social distances: 1, 20, 100. Some example questions were “What did/will this person have for lunch today?”, “Where did/will this person have lunch today?”, and “What did/will this person drink at lunch today?” The person (social distance) qualifiers coincided with the same social distances used in the social discounting task.

Control condition

Participants completed three blocks of questions as in the experimental condition, with the exception that questions were regarding activities of the self (e.g., “What did/will you have for lunch today?”, “Where did/will you have lunch today?”, and “What did/will you drink at lunch today?”). The questions were identical to the experimental condition, with the exception of the person qualifier (self rather than other). See Appendix B for all episodic thinking questions in both experimental and control conditions.

Procedure

Before the start of the trials associated with each social distance, a block of episodic thinking questions were administered. In the experimental condition, questions regarding the “other” at social distance 1, 20, and 100 preceded assessment of social discounting at social distance 1, 20, and 100, respectively. In the control condition, discounting for all social distances were preceded by questions regarding the self. All measures and manipulations are fully reported here.

Analytic Plan

Manipulation Check

Again, two blind raters coded each response on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (completely abstract) to 7 (completely concrete). Correlations between raters were positive and significant in both experimental (r[131] = 0.54, 95% CI: (0.41, 0.65)) and control (r[144] = 0.54, 95% CI: (0.41, 0.65)) conditions. Overall, participants answered questions concretely, with high mean concreteness ratings in both experimental and control conditions (4.98, s=1.31. vs. 4.94, s=1.37, difference=0.04, 95% CI: (−0.28, 0.36)).

Social Discounting

Indifference points were calculated as the midpoint of the lowest amount for the self where the outcome for the self was selected and the highest amount for the self where the outcome for the other was selected. Indifference points for exclusive preference for the self and other were scored as $100 and $12.50, respectively. When an inconsistent pattern of responding did not allow for calculation of an indifference point, social discount rate s was calculated excluding this indifference point as long as the participant provided two usable indifference points. Participants who provided fewer than two usable indifference points were excluded from the analyses.

Means of social discounting were compared between the experimental (other) and control (self) groups with a two-sample t-test.

Results

Participant demographics (Table 1) were not found to be associated with social discounting, and not included in the main analysis. Table 2 reports social discounting descriptive statistics. Goodness-of-fit measures were X̄R2 = .82, SDR2= .20 and X̄RMSE = .073, SDRMSE = .048. Those in the experimental condition had a mean discounting of −1.58, which was significantly lower than that for the control participants by 0.74 (95% CI: (0.19, 1.28), t[273] = 2.67, p=0.008, Cohen’s d = .322).

Discussion

Using an independent-groups design, study 2 replicated the statistically significant difference between experimental and control conditions observed in the control-experimental order of study 1. This result enhances confidence that the difference in social discounting observed as a function of episodic thinking of others is a reliable phenomenon, particularly given that the generalizability of the phenomenon is expanded in study 2 using a sample with very different demographics as the college student sample of study 1.

Despite this, a significant challenge to the interpretation of the results in studies 1 and 2 is that simply thinking about others, episodically or not, resulted in decreased social discounting. Associated with this is the possibility of experimenter demand, given that participants were directed to think about individuals at specific social distances while concurrently making choices for outcomes to those individuals. Study 3 was designed to address this alternative explanation.

Study 3

The influential Construal Level Theory (Liberman & Trope, 2008; Trope & Liberman, 2003) states that: (1) interpersonal, temporal, and other dimensions of distance can be reduced to a single dimension of psychological distance; and (2) mental representations of psychologically proximal events are characterized by concrete, low-level construal while representations of distal events are characterized by abstract, high-level construal. Synthesis of Construal Level Theory and the established literature on episodic future thinking suggests that self-control is promoted by creating asynchrony of concrete construal (associated with psychological proximity) and psychologically distal (future) outcomes. If so, episodic thinking of others may promote altruism by creating asynchrony of concrete construal and psychologically distal (others’) outcomes. Importantly, an extensive body of Construal Level Theory research (see review in Liberman & Trope, 2014) indicates that activation of a level of construal on one dimension of psychological distance should impact decisions on other dimensions of psychological distance. Based on this principle, episodic thinking in a domain of psychological distance other than social distance (i.e., time in the future) should still impact decision making in the domain of social distance (i.e., social discounting). Change in social discounting as a function of episodic future thinking would address the possibility that simply thinking about others resulted in decreased social discounting. Across two counterbalanced sessions, study 3 was similar to the design of study 1: participants engaged in episodic future thinking (experimental condition) or episodic present thinking (control condition) while completing a social discounting task.

Method

Participants

Fifty undergraduate psychology students at the University of Maryland enrolled in the study for course credit. Given the similar design, the recruitment target was informed by study 1. Four participants were excluded for the following reasons: did not follow directions (two), did not understand English (one), and research staff error (one). Two participants provided usable data for only one condition; this was not systematic so data in those conditions was retained. Forty-six remaining participants provide complete datasets. There was no overlap with participants in study 1.

Materials

Social Discounting task

The computerized, binary choice, social discounting task was identical to the one administered in study 1, with social distances of: rank order 1, 10, 20, and 100.

Episodic Thinking conditions

Experimental condition

Participants completed four blocks of paper-and-pencil episodic thinking questions, designed to prime episodic, concrete thinking about the future. Each block was comprised of five fill-in-the-blank questions regarding specific events/activities (having lunch, visiting a website, engaging in a leisurely activity, and completing a task) that would occur 1 week, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years from now (e.g., “What will you have for lunch one week from today?”, “Where will you have lunch one week from today?”, and “What will you drink at lunch one week from today?”).

Control condition

Participants completed four blocks of paper-and-pencil episodic thinking questions similar to the experimental condition, with the exception that questions were regarding specific events that would occur “today” (e.g., “What did/will you have for lunch today?”, Where did/will you have lunch today?”, and “What did/will you drink at lunch today?”). The questions were identical to the experimental condition, with the exception of the time qualifier (future or present). See Appendix C for all episodic thinking questions in both experimental and control conditions.

Procedure

The experimental design and the assessment of social discounting were identical to study 1. The only difference was the use of episodic future thinking and episodic present thinking manipulations as the experimental and control conditions, respectively. Before the start of the trials associated with each social distance, a block of episodic thinking questions were administered. In the experimental condition, questions regarding events 1 week, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years in the future preceded assessment of social discounting at social distance 1, 10, 20, and 100, respectively. In the control condition, discounting for all social distances were preceded by questions regarding today. All measures and manipulations are fully reported here.

Analytic Plan

Manipulation Check

Again, two blind raters coded each response from both episodic thinking manipulation on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (completely abstract) to 7 (completely concrete). Correlations between raters were positive and significant in both experimental (r[43] = 0.54, 95% CI: (0.28, 0.72)) and control (r[43] = 0.69, 95% CI: (0.49, 0.82)) conditions. Overall, participants answered questions concretely, with high mean concreteness ratings in both experimental and control conditions (5.14, s=.46 vs. 5.44, s=.32, difference=−0.29, 95% CI: (−0.43, −0.16)).

Social Discounting

As in study 1, social discounting measures were calculated, transformed, and analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA. The ANOVA had episodic thinking condition (experimental: future vs. control: today) as the within-individual factor and order (experimental-control vs. control-experimental) as an among-individual condition. Given the episodic thinking × order interaction observed in study 1, the same interaction was predicted a priori in study 3.

Results

Participant demographics (Table 1) were not found to be associated with social discounting and not included in the main analysis. Table 2 reports social discounting descriptive statistics. Goodness-of-fit measures were X̄R2 = .82, SDR2 = .20 and X̄RMSE = .073, SDRMSE= .048. Rates of social discounting between conditions were positively correlated: Pearson’s r(44)=0.85 (95% CI: (0.75, 0.92)).

A 2×2 ANOVA examining the effects of condition, order, and their interaction revealed an interaction (F[1,42] = 3.21, p=.081) that was not statistically significant, with no significant main effects (both p>.28; Figure 1, bottom panel). As in study 1, simple effects contrasts revealed significantly lower social discounting in the experimental condition compared to control (t[42]=2.03, p=.048, η2G = .089, diff = 0.57, 95% CI: (0.004, 1.13)) only when the control condition occurred first; no effect was observed conditions when the experimental conditions occurred first (t[42]=0.50, p=.62, η2G =.006, diff = −0.14, 95% CI: (−0.70, 0.42)).

Discussion

The present study examined the effect of episodic future thinking, compared to episodic present thinking, on social discounting. As with study 1, the hypothesis that social discounting would be reduced following episodic future thinking was partially supported. The pattern of results was similar to study 1, where the predicted difference was observed only when participants were first exposed to the control condition followed by exposure to the experimental condition. The fact that essentially the same pattern of results was observed across two different studies with two different episodic thinking manipulations increases the likelihood that the observed interaction is a genuine phenomenon, and we are more confident that our proposed explanation of carryover effects has merit.

More importantly, we believe the present results provide strong evidence against potential alternative explanations for the results observed in studies 1 and 2. Given that the episodic thinking manipulation of study 3 prompted participant to think about the future, the resulting decrease in social discounting cannot be due to thinking about others. Moreover, because the episodic thinking manipulation included no mention of others, it would appear to be highly unlikely that participants deciphered the study hypothesis and were responding to experimenter demand.

General Discussion

The present studies provide initial evidence that shifting episodic perspective to that of others or of the future can decrease social discounting. Studies 1 and 2 specifically capitalized on insights from the related topics of episodic future thinking and delay discounting, finding that episodic thinking of others reduced social discounting. This expands on research indicating that perspective-taking mediates altruism (Oswald, 1996; Gummerum & Hanoch, 2012; see review in Underwood & Moore, 1982). Because a potentially problematic interpretation of studies 1 and 2 was that simply thinking about others reduced social discounting, study 3 examined the impact of episodic future thinking on social discounting. Consistent with a principle of Construal Level Theory, which indicates that activation of low-level construal on a temporal dimension of psychological distance should impact decisions on an interpersonal dimension of psychological distance, priming individual to think episodically about future events resulted in relative preference for outcomes to others.

We believe that the results of study 3 are particularly compelling given that the connection across various dimensions of psychological distance noted by Construal Level Theory, specifically between temporal and interpersonal dimensions, may have roots in brain structure and development. There is an expansive body of research on brain regions associated with the construction of alternative perspectives (i.e., simulation, see review in Buckner & Carroll, 2007). Prospection (thinking about the future) and theory-of-mind (assignment of mental states to others) are forms of simulation thought to be controlled by common/contiguous regions of the brain (Gallagher & Frith, 2003; Mesulam, 2002; Saxe & Kanwisher, 2003) that emerge during the same developmental period (Perner & Ruffman, 1995). Thus the time-based episodic thinking manipulation of study 3 not only addressed a potential challenge to the interpretation of studies 1 and 2, but also highlights a novel approach to reduce social discounting.

The qualifying condition under which we observed the predicted results warrants consideration. The condition × order interaction observed in studies 1 and 3 indicates that order impacts the effect of the manipulation. Specifically, the reduction in social discounting was observed when exposure to the experimental condition occurred second; when the experimental condition occurred first, no difference was observed between conditions. While this carryover effect may appear to be a limitation within the studies given that order complicated the results, we believe such carryover has positive implications for implementation of episodic thinking approaches to reducing social discounting. The implementation of episodic thinking approaches could capitalize on the fact that such shifts in thinking are not fleeting, and seek to expand the circumstances in which a mindset shift impacts behavior.

Some limitations of the studies are noteworthy. First, though previous research indicates no difference in social discounting of real and hypothetical rewards (Locey, Jones, & Rachlin, 2011), we cannot definitively rule out different effects using real rewards. Second, the present series of studies did not include a condition with no episodic thinking. Our assumption was that the control condition in each study was consistent with the default level of construal and had no effect on social discounting. Moreover, we believed it was important that the different conditions be matched on some episodic thinking task. However, it is possible that all control conditions of the present studies enhanced preference for outcomes for the self, resulting in elevated social discounting in the control conditions rather than (or in conjunction with) decreased social discounting in the experimental conditions. The inclusion of a condition in future research with no episodic thinking manipulation will be able to address this question. Finally, the present study is unable to disentangle a number of factors that may constitute concrete or episodic thinking: Vividness of the imagery, precision of visuospatial details, degree of affective intensity, and other features may define concreteness. In addition, the present study is unable to rule out the possibility that simply thinking about others and/or the future (e.g., attention), independent of the episodic nature of the thought, reduces social discounting. The present study was not designed to unravel these more-nuanced features of episodic thinking, and future research should seek to determine a more precise mechanism for the increase in altruism resulting from episodic thinking of others and the future.

Despite these limitations, the present studies constitute a novel approach to the study of altruism, and provide initial evidence that innovative approaches to prospective thinking could positively impact engagement in prosocial behaviors. High rates of social discounting are associated with behaviors that result in negative consequences for others (Bradstreet et al, 2012; Sharp et al., 2012), and approaches that reduce social discounting could impact a variety of outcomes associated with altruism.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Approaches to enhance altruism can positively impact individuals and societies.

In three studies, we examine the influence of episodic thinking, using social discounting as an index of altruism.

Use of episodic thinking to imagine other’s scenarios reduced social discounting.

Use of episodic thinking to imagine the self in the future reduced social discounting.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by NIDA grant DA11692. NIDA had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report, nor in the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Richard Yi, Email: ryi1@umd.edu.

Alison Pickover, Email: mpckover@memphis.edu.

Allison M. Stuppy-Sullivan, Email: alli.stuppy@gmail.com.

Sydney Baker, Email: sbaker@terpmail.umd.edu.

Reid D. Landes, Email: RDLandes@uams.edu.

References

- Ainslie GW. Picoeconomics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Atance CM, O’Neill DK. Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2001;5:533–539. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P. Evolutionary economics of mental time travel. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2008;12:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradstreet MP, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Skelly JM, Lynch ME, Trayah MC. Social discounting and cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2012;25(5):502–511. doi: 10.1002/bdm.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Carroll DC. Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11(2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TO, Stanton CM, Epstein LH. The future is now: comparing the effect of episodic future thinking on impulsivity in lean and obese individuals. Appetite. 2013a;71:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TO, Stanton CM, Epstein LH. The future is now: Reducing impulsivity and energy intake using episodic future thinking. Psychological Science. 2013b;24:2339–2342. doi: 10.1177/0956797613488780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Green L, Myerson J. Cross-cultural comparisons of discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Record. 2002;52:479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Gaesser B. Constructing memory, imagination, and empathy: a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;3:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaesser B, Schacter DL. Episodic simulation and episodic memory can increase intentions to help others. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:4415–4420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402461111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Frith CD. Functional imaging of ‘theory of mind’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummerum M, Hanoch Y. Altruism behind bars: Sharing, justice, perspective taking and empathy among inmates. Social Justice Research. 2012;25(1):61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1964a;7:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1964b;7:17–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16(3):264. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y. The psychology of transcending the here and now. Science. 2008;322(21):1201–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1161958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y. Traversing psychological distance. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2014;18:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Epstein LH. Living in the moment: Effects of time perspective and emotional valence of episodic thinking on delay discounting. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;128:12–19. doi: 10.1037/a0035705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM. The human frontal lobes: transcending the default mode through contingent encoding. In: Stuss DT, Knight RT, editors. Principles of Frontal Lobe Function. Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 8–30. [Google Scholar]

- Olejnik S, Algina J. Generalized eta and omega squared statistics: Measures of effect size for some common research designs. Psychological Methods. 2003;8(4):434–447. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald PA. The effects of cognitive and affective perspective taking on empathic concern and altruistic helping. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;136(5):613–623. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1996.9714045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner J, Ruffman T. Episodic memory and autonoetic conciousness: developmental evidence and a theory of childhood amnesia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1995;59(3):516–548. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Büchel C. Episodic future thinking reduces reward delay discounting through an enhancement of prefrontal-mediotemporal interactions. Neuron. 2010;66:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Altruism is a form of self-control. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2002;2:284–291. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Jones BA. Social discounting and delay discounting. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2008;21:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Read D. Intrapersonal dilemmas. Human Relations. 2001;54:1093–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Kanwisher N. People thinking about thinking people: the role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, Buckner RL. Episodic simulation of future events: Concepts, data, and applications. The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:39–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Barr G, Ross D, Bhimani R, Ha C, Vuchinich R. Social discounting and externalizing behavior problems in boys. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2012;25(3):239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Temporal construal. Psychological Review. 2003;110(3):403–421. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RN, Crisp RJ. Imagining intergroup contact reduces implicit prejudice. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;49:129–142. doi: 10.1348/014466609X419901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RN, Crisp RJ, Lambert E. Imagining intergroup contact can improve intergroup attitudes. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2010;10:427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood B, Moore B. Perspective-taking and altruism. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;91(1):143. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.