Abstract

Nonadherence in the management of chronic illness is a pervasive clinical challenge. Although researchers have identified multiple correlates of adherence, the field remains relatively atheoretical. The authors propose a cognitive–affective model of medication adherence based on social support theory and research. Structural equation modeling of longitudinal survey data from 136 mainly African American and Puerto Rican men and women with HIV/AIDS provided preliminary support for a modified model. Specifically, baseline data indicated social support was associated with less negative affect and greater spirituality, which, in turn, were associated with self-efficacy to adhere. Self-efficacy to adhere at baseline predicted self-reported adherence at 3 months, which predicted chart-extracted viral load at 6 months. The findings have relevance for theory building, intervention development, and clinical practice.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, antiretroviral, adherence, social support, self-efficacy, depression

Each year in the United States, 500,000 physicians write 1.8 billion prescriptions involving 55,000 pharmacies (Besch, 1995). However, many of these prescribed medications are never taken, with rates of nonadherence ranging from 15% to 93% (Haynes, McKibbon, & Kanani, 1996). Among persons with chronic illnesses, nonadherence is especially problematic, occurring in 20% to 82% of cases (Cramer, Mattson, Prevey, Scheyer, & Ouellette, 1989; de Klerk & van der Linden, 1996; Geest et al., 1995). The effects of nonadherence range from individual disability (e.g., arthritis pain) to global threat (e.g., development of treatment-resistant virus). The yearly monetary costs exceed $100 billion (Deeks, Smith, Holodniy, & Kahn, 1997).

With respect to HIV/AIDS in particular, the importance of adherence to prescribed treatments is paramount. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has demonstrated remarkable success in inhibiting viral replication and reducing morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs for HIV-positive persons (Hogg et al., 1998; Palella et al., 1998; Valenti, 2001). The efficacy of ART, however, depends on strict adherence to dosing regimens. As adherence decreases, viral loads and the risk of progression to AIDS increase (Bangsberg et al., 2001; Low-Beer, Yip, O’Shaughnessy, Hogg, & Montaner, 2000; Paterson et al., 2000), as does the likelihood of generating treatment-resistant strains of HIV (Salomon et al., 2000) and of infecting others (Quinn et al., 2000). Despite these risks, nonadherence to ART is widespread (Bangsberg et al., 2000; Bartlett, 2002; Gordillo, Amo, Soriano, & Gonzalez-Lahoz, 1999; Nieuwkerk et al., 2001).

The development of efficacious intervention strategies to promote adherence in chronic illness depends in large part on the identification of key correlates of adherence and a comprehensive conceptualization or working model of their relationship to adherence behaviors. Fortunately, a large body of research has already led to the identification of multiple factors associated with adherence to medication regimens for chronic illness, most of which fit within the typology created by Ickovics and Meisler (1997): characteristics of the patient, the patient–provider relationship, the illness or treatment regimen, and the context in which medical care is delivered. A substantial amount of research has identified correlates of adherence to ART specifically (Bartlett, 2002; Bozette, 1995; Chesney et al., 2000; Eldred, Wu, Chaisson, & Moore, 1998; Erickson, Ascione, Kirking, & Johnson, 1998; Friedland & Williams, 1999; Gifford et al., 2000; Ickovics & Meisler, 1997; Kalichman, Ramachandran, & Catz, 1999; Rosenstock, 1975; Singh et al., 1996; Smith, Kirking, & ACSUS [AIDS Costs and Services Utilization Survey], 2001). However, there is no well-validated and overarching theory of adherence that integrates findings on adherence correlates that can be generally applied across varying medical conditions.

Multiple studies have confirmed the positive association between social support and adherence to medication regimens across different chronic illnesses (Becker & Maiman, 1980; Caplan, Harrison, Wellons, & Frech, 1980; Doherty, Schrott, Metcalf, & Iasiello-Vailas, 1983; Earp, 1979; Haynes, 1979; Kirscht, Kirscht, & Rosenstock, 1981; Morisky et al., 1983), as well as adherence to ART in particular (Catz, Kelly, Bogart, Benotsch, & McAuliffe, 2000; Gallant & Block, 1998; Gordillo et al., 1999; Holzemer et al., 1999; Remien, Wagner, Dolezal, & Carballo-Dieguez, 2003; Singh et al., 1999), although few studies have focused specifically on the role of social support. The social support literature refers to major functions of support that serve to bolster health, such as control and mastery, self-acceptance and esteem, and social interaction (Albrecht & Adelman, 1987; Uchino, 2004), and references social psychological theories on social exchange, social comparison, self-esteem, and personal control (Wills, 1982), as well as social support–specific theories (Kaplan & Toshima, 1990; Veiel & Baumann, 1992). However, the precise mechanisms of support that affect health outcomes and behaviors, especially adherence to medical regimens, have not been adequately conceptualized or empirically examined (DiMatteo & DiNicola, 1982; Meichenbaum & Turk, 1987; Uchino, 2004; Wills & Fegan, 2001). Notable exceptions in the area of HIV include Gonzalez et al. (2004), who focused on the mediators of depression and positive states of mind, and Weaver et al. (2005), who proposed a stress and coping model of antiretroviral adherence.

We propose a working model of how social support enhances adherence that is based on our earlier pilot work (Simoni, Frick, Lockhart, & Liebovitz, 2002). Although we focused on antiretroviral adherence in the present study, the model may be applicable to other chronic illness regimens. On the basis of a cognitive–affective framework, the model stresses functional over structural aspects of support, that is, it assumes that perceptions of received support and satisfaction with support are more important than the size or density of one’s social network. In line with functional analyses of support, it highlights specific types of support identified by social support theorists (i.e., appraisal, emotional, and informational; House & Kahn, 1985), as well as a novel type we have hypothesized (i.e., spiritual). This model presumes the effects of social support are not direct or buffering but rather are mediated by cognitive and affective variables.

Appraisal support, in the form of encouragement, feedback, and affirming statements, as well as modeling from supportive others, is thought to increase one’s self-efficacy to adhere, which is related to antiretroviral adherence (Gifford et al., 2000; Ickovics & Meisler, 1997; Johnson et al., 2003) in accordance with Bandura’s (1997) social learning theory.

Emotional support, or listening, caring, and empathic companionship, is seen as decreasing negative affect (Veiel & Baumann, 1992), perhaps by encouraging adaptive coping or increasing self-esteem. Depressive symptomatology is one of the most consistent predictors of nonadherence (Chesney et al., 2000; Gordillo et al., 1999; Mehta, Moore, & Graham, 1997; Paterson et al., 2000; Singh et al., 1996; Treisman, Angelina, & Hutton, 2001), perhaps because depressed patients lack the physical and mental energy and sustained motivational level to maintain high levels of adherence (J. S. Tucker et al., 2004). Additionally, depressed patients frequently have feelings of hopelessness toward themselves and their future and may not fully appreciate the association of medication adherence to improved health outcomes. Finally, they may be more prone to cognitive impairment or forgetfulness, which can impede adherence. There is less empirical support regarding the association between stress and adherence, although we predicted that feelings of being overwhelmed, when combined with medication side effects or declining health, would detract from the ability to manage medication adherence. Although the evidence is mixed regarding the association between anxiety and adherence (DiMatteo, Lepper, & Croghan, 2000; J. S. Tucker et al., 2004)—perhaps because moderate levels of anxiety may encourage rather than detract from adherence—we considered anxiety to be more similar to depressive symptomatology and stress than different and combined the three factors in this preliminary model.

Informational support, in the form of the provision of facts, advice, and guidance about HIV disease, ART regimens, and adherence strategies, is seen as capable of bolstering ART knowledge (Eldred et al., 1998; Wagner, Remien, Carballo-Dieguez, & Dolezal, 2002). The knowledge that ART is effective and that poor adherence may promote viral resistance and treatment failure has been shown to affect patients’ ability to adhere to their medications (Wagner et al., 2002). Less adherent patients in HIV clinical trials were less sure of the link between nonadherence and the development of resistance than other patients (Chesney et al., 2000), and many patients have reported inadequate knowledge as a main barrier (Roberts, 2000).

Spiritual support, in the form of encouraging spiritual coping, praying with an individual, or suggesting there is a sacred purpose or larger meaning in life, was hypothesized to bolster spirituality. Although the effect of spirituality on medication adherence per se is undocumented, persons diagnosed with life-threatening illnesses such as cancer and HIV/AIDS have reported high levels of spirituality (Connor, Wicker, & Germino, 1990; Jenkins, 1995; Jenkins & Pargament, 1995; Schwartzberg, 1993; Zinnbauer et al., 1997), which have been highly correlated with psychological adaptation and good health outcomes (Kaczorowski, 1989; Simoni, Kerwin, & Martone, 2002).

In the present study, we interviewed patients at an inner-city outpatient HIV clinic to test our proposed model of adherence. In addition to model components, we included three potentially confounding factors: side effects, substance use, and social desirability (Arnsten et al., 2001; Ickovics & Meisler, 1997; Remien et al., 2003; J. S. Tucker et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2002).

Method

Participants

The final sample consisted of 136 participants, 61 (45%) of whom were women. Most were African American (46%) or Puerto Rican (39%). Mean age was 42.6 years (SD = 8.9, range = 20.1–77.7). Fifty-six percent had at least a high school education or GED, 15% were employed full or part time, and 81% reported a total monthly income of less than $1,000. Eighty-three percent classified their sexual orientation as exclusively heterosexual, 10% as bisexual, and 6% as exclusively homosexual. Only 16% were currently legally married, although 50% reported a current steady sexual partner. Twenty-nine percent reported ever injecting illicit drugs. Participants reported contracting HIV from 2 months to 18.6 years previously (M = 7.8 years, SD = 4.6), and 63% had started their first ART regimen over 2 years previously.

Measures

Social support

We used a modified version of the University of California, Los Angeles, Social Support Inventory (Schwarzer, Dunkel-Schetter, & Kemeny, 1994) to assess received social support as well as overall satisfaction with social support received in the past 30 days. Four items (α = .69) queried the frequency of received support from 1 (not very often) to 4 (very often) from anyone (i.e., “family, friends, buddies, and doctors or other clinic staff”) in the following four areas of support: appraisal support (“made you feel confident that you could succeed at doing whatever you set your mind to do”), informational support (“provided information about your HIV medications or offered advice and suggestions to help you take them), emotional support (“talked openly to you about things that might be worrying you and listened and tried to understand”), and spiritual support (“encouraged and guided you to turn to God or your own spirituality for support”). Note that only the informational support component was specific to ART. Four additional items queried level of satisfaction with each type of support from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied); α = .75. Social support functions were combined in the analyses as previous research has demonstrated the difficulty of statistically discriminating their effects. The overlap likely reflects the reality that other persons generally provide multiple types of support (House & Kahn, 1985).

Adherence

On the basis of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) measure of patient self-report of ART medications taken over the previous 3 days (Chesney et al., 2000), we computed three measures of adherence: dose adherence (percentage of doses taken over the total number of doses prescribed), pill adherence (percentage of medications taken for which the correct number of pills was taken for each prescribed dose), and time adherence (percentage of medications for which each dose was taken within 2 hours of when it was supposed to be taken). For each of these three adherence measures, daily percentages were averaged for the 3-day assessment period.

Viral load

As a clinical outcome measure, we extracted chart data on the HIV viral load taken closest in time to the 6-month interview.

Self-efficacy to adhere

To assess participants’ self-efficacy to adhere to their prescribed medications, we created five items—for example, “Over the next 4 weeks, how sure are you that you will be able to … take your HIV medications at the times you are supposed to?”—scored on a Likert-type response scale from 1 (not at all sure) to 4 (extremely sure).

Negative affect

We assessed depressive symptomatology, anxiety, and stress as separate measures of negative affect.

Participants completed the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), a nondiagnostic screening measure for examining the prevalence of nonspecific psychological distress in community samples. The scale’s 20 items assessing depressive symptomatology in the previous week (e.g., “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me”) are rated from 0 (rarely or none of the time/less than one day in the past week) to 3 (most or all of the time/5–7 days in the past week). Many studies have demonstrated the measure’s validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability (8-week interval: r = .59; Radloff, 1977). In this study, α = .89.

Participants also completed the 11-item anxiety subscale of the Psychiatric Symptom Index (Ilfeld, 1976), which rates the presence of symptoms in the past 2 weeks (e.g., “Did you have to avoid certain things, places, or activities because they frighten you?”) from 1 (never) to 4 (very often). Normative data for this measure indicated an alpha of .85; in this study, α = .90.

Finally, participants completed the short version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) to address how often general stress had been experienced in the past 30 days (e.g., “How often have you felt that difficulties were piling up so high you could not overcome them?”). Answers are rated 0 (never) through 4 (very often). The four items in the short version of the PSS were selected because they correlate most highly with the full 14-item PSS. The PSS has adequate internal and test–retest reliability (Cohen et al., 1983); in this study, α = .68.

Spirituality

The Systems of Belief Inventory (Holland et al., 1998) was designed to measure religious and spiritual beliefs and practices, as well as the social support derived from a community sharing those beliefs. It is divided into 11 items assessing spirituality (e.g., “I feel certain that God in some form exists”) and 4 items assessing spiritual coping (e.g., “Prayer or meditation has helped me cope during times of serious illness”). Responses are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). The scale has exhibited good internal consistency; test–retest reliability; and convergent, divergent, and discriminant validity in both physically healthy and physically ill individuals (Holland et al., 1998). In this study, the alpha for spirituality was .91, and the alpha for spiritual coping was .84.

ART-related knowledge

Participants’ knowledge about ART adherence, such as the possibility of developing treatment-resistant strains of HIV and the dangers of drug holidays, was assessed with four items created for this study scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 4 (extremely true; e.g., “The best way to treat side effects of HIV medications is to stop taking them for a little while”). Because of their unacceptably low internal consistency (α = .39), the knowledge items were omitted from further analyses.

Side effects

According to an AACTG instrument (Justice et al., 2001), participants rated how troubled they were in the past 30 days by 20 common side effects of highly active ART (HAART) medications (e.g., “fevers, chills, or sweats” and “pain, numbness, or tingling in the hands or feet”) scored from 0 (don’t have symptom) to 4 (bothers me tremendously). In this study, α = .91.

Substance use

Participants indicated whether they had ever in their lives used alcohol, heroin, marijuana, crack cocaine, speed, or nonprescribed injection drugs. For each substance used, participants indicated whether they had ever used the substance more than 3 times a week for at least one month (i.e., “heavy use”) and how many days among the past 30 they had used the substance.

Social desirability

We included a scale to assess social desirability or the tendency of individuals to describe themselves in favorable terms to achieve the approval of others (Crowne & Marlow, 1964). The scale’s 10 items consist of 5 socially desirable but probably untrue items and 5 socially undesirable but probably true statements. Internal consistency (α = .88) and test–retest reliability (α = .88) are reportedly high (Crowne & Marlow, 1964). For this study, α = .61.

Procedure

Participants were recruited as part of an intervention trial at a public outpatient HIV clinic in the Bronx, New York, from May 2000 to March 2002. During each recruitment session, research assistants (RAs) screened all patients in the clinic waiting area for eligibility (i.e., at least 18 years of age, proficient in English, not psychotic or demented, on ART) based on chart review and staff assessment. RAs approached all eligible patients and briefly explained the study to them. Interested patients were required to attend a later meeting (i.e., the baseline) to be consented, enrolled, and randomized. RAs conducted face-to-face structured interviews at baseline, at the end of a 3-month social support intervention, and at 6 months postbaseline. Participants returned to the clinic to complete each assessment. Retention of the baseline sample was 77% at 3 months and 85% at 6 months.

Data Analysis

First, we calculated descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and ranges, for all the main variables.

Next, to identify potentially confounding variables that would need to be controlled in later analyses, we used bivariate analyses (i.e., Pearson correlations, t tests, and chi-squares) to examine the association of each measure of adherence with sociodemographic factors (i.e., sex, ethnicity, age, education, income, employment, sexual orientation, and relationship status) and medical-related variables (i.e., AIDS diagnosis, time since HIV diagnosis, time since initiation of first HAART regimen, drug class, number of medications in regimen, number of doses in regimen, and viral load), as well as side effects, substance use, and social desirability.

Finally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to evaluate the proposed model. SEM examines the structural relationships among all constructs, including latent variables in the model with measurement errors. To enhance causal interpretations of the findings, we used all three waves of data. Measures of social support and all mediators were based on baseline data, adherence measures were based on 3-month data, and data from chart review at 6 months were used to estimate viral load. Because the data were drawn from a two-arm randomized controlled trial of a social support intervention delivered between the baseline and 3-month interviews, we controlled for experimental condition in all relevant analyses.

SEM analysis was evaluated with the maximum-likelihood estimation and performed with Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 1999). Several goodness-of-fit indices were used in addition to the chi-square statistic that is sensitive to both the assumption of normality and sample size. Specifically, the overall model fit was assessed by examining the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) index, with values around .05 (the lower bound of the 90% CI under .05) indicating adequate fit (Bollen & Long, 1993; Browne & Cudeck, 1993); the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990); and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; L. R. Tucker & Lewis, 1973), which indicates an adequate fit with values around .90 or greater (Newcomb, 1990, 1994). Missing data were imputed within the software so that all available data were utilized.

Results

Descriptive Data

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for all main variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data on Main Study Variables Among 136 HIV-Positive Individuals

| Variable | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline measures | |||

| Received support | 2.24 | 0.81 | 1–4 |

| Satisfaction with support | 3.13 | 0.71 | 1–4 |

| Depressive symptomatology | 0.99 | 0.56 | 0–2.55 |

| Anxiety | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0–3 |

| Stress | 1.52 | 0.84 | 0–3.60 |

| Self-Efficacy | |||

| Item 1 | 3.17 | 0.78 | 1–4 |

| Item 2 | 2.24 | 0.81 | 1–4 |

| Item 3 | 2.89 | 1.05 | 1–4 |

| Item 4 | 3.79 | 0.63 | 1–4 |

| Item 5 | 2.61 | 1.19 | 1–4 |

| Spirituality | 2.40 | 0.64 | 0.27–3.00 |

| Spiritual coping | 2.05 | 0.82 | 0–3 |

| 3-month measures | |||

| Dose adherence | 0.80 | 0.34 | 0–1 |

| Pill adherence | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0–1 |

| Time adherence | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0–1 |

| 6-Month Measures | |||

| Ln viral load | 7.17 | 3.04 | 3.91–13.53 |

| Experimental condition (0 = control, 1 = experiment) |

0.49 | 0.50 | 0–1 |

Note. Ln = natural log.

Bivariate Analyses

In bivariate analyses, none of the three adherence variables were related to any sociodemographic or medical-related variable or to side effects, substance use, or social desirability. Therefore, none of these variables were controlled in the SEM.

Model Testing With SEM

The model we tested, which was specific to antiretroviral adherence in this sample, included a medical outcome (i.e., viral load) and omitted knowledge, resulting in five latent factors (i.e., social support, negative affect, spirituality, self-efficacy to adhere, and adherence) and one measured construct (i.e., viral load).

A preliminary confirmatory factor analysis indicated adequate fit, χ2(80, N = 136) = 116.34, p = .005, CFI = .96, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .06 (.03, .08). The five latent factors were measured adequately by their respective indicators, and factor loadings of all indicators were high for the latent variables. Intercorrelations among the constructs are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among the Five Latent Constructs Among 136 HIV-Positive Individuals

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social support | — | ||||

| 2. Negative affect | −0.42** | — | |||

| 3. Spirituality | 0.46*** | −0.26* | — | ||

| 4. Self-efficacy | 0.35** | −0.35*** | 0.46*** | — | |

| 5. Adherence | 0.13 | −0.20† | −0.09 | 0.15 | — |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

A test of our model proposing that negative affect, spirituality, and self-efficacy mediate the effect of social support on adherence (controlling experimental condition) resulted in an adequate fit to the data: χ2(112, N = 136) = 162.57, p = .001. RMSEA was within range (.06 [.04, .08]), and both the CFI (.94) and the TLI (.93) exceeded the benchmark criterion of .90. However, a closer look at the significance level of the path coefficiencies showed that although most of the estimated paths were significant, none of the paths from the mediating constructs to the constructs of adherence was significant at less than .05, with level of significance of self-efficacy to adherence at .06. We also checked the modification index, which indicated there are strong relationships between spirituality and self-efficacy and between negative affect and self-efficacy.

Therefore, we then ran a modified model, hypothesizing that there would be a two-tiered relationship between the three mediating constructs, with negative affect and spirituality in the first tier and self-efficacy in the second tier. We hypothesized that social support would directly influence negative affect and spirituality, which would influence self-efficacy, which would influence adherence.

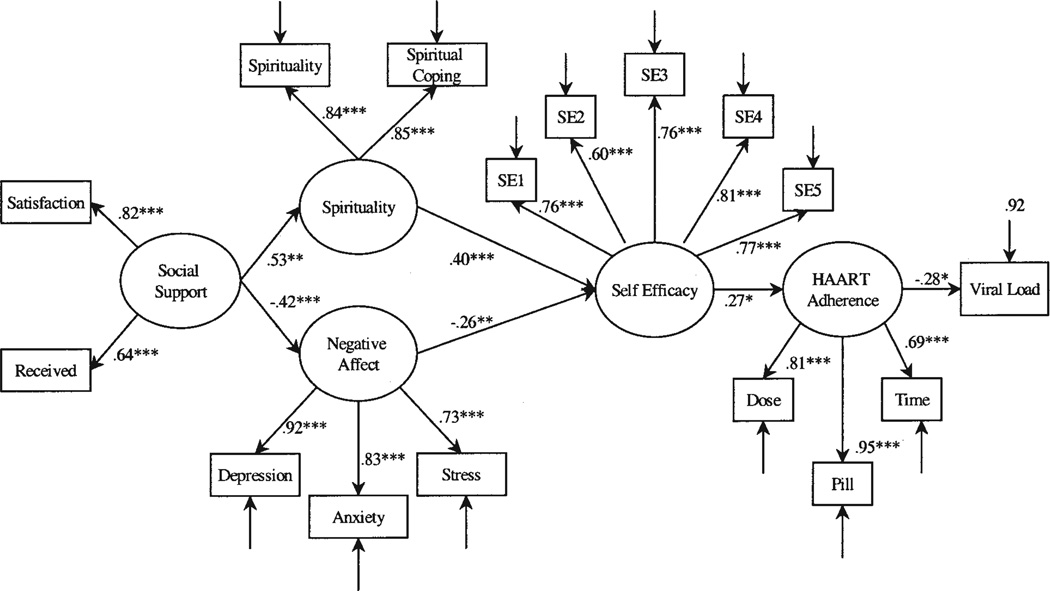

The new model (see Figure 1) fit the data very well: χ2(113, N = 136) = 152.78, p = .008, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05 (.03, .07). All the hypothesized paths (shown in the model) were significant, representing all factor loadings of the latent constructs. As shown, baseline data indicated that social support predicted lower levels of negative affect and greater spirituality, which in turn predicted self-efficacy to adhere. Baseline self-efficacy to adhere predicted 3-month adherence, which predicted viral load at 6 months. Social support was not directly related to adherence or viral load; however, it had an indirect effect via less negative affect and greater spirituality and self-efficacy to adhere. Squared multiple correlations indicated that this model accounted for 8% of the variance in adherence at 3 months and 8% of the variance in viral load at 6 months.

Figure 1.

Final model of social support and adherence among 136 HIV-positive individuals. HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy; SE# = Self-Efficacy item number.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Discussion

Nonadherence in the management of chronic illnesses is a common and serious problem that has frustrated care providers, negatively impacted individual health, and burdened society in terms of both adverse health outcomes and staggering economic costs. Although correlates of adherence have been identified, the field lacks a well-validated model that could contribute to theory development and the design of efficacious interventions.

In this study of 136 HIV-positive men and women in the Bronx, New York, we proposed a cognitive–affective model of the effects of social support on medication adherence based on social support theory and the relevant empirical literature. Model testing with SEM provided support for a modified version of our model. The final model indicated that negative affect, spirituality, and self-efficacy to adhere mediated the relationship between social support and adherence. However, contrary to the model originally proposed, self-efficacy to adhere was not directly associated with social support. Instead, social support acted through the other two mediators on self-efficacy to adhere, which was directly related to later adherence. This finding indicates that self-efficacy to adhere is an important correlate of adherence although it is not directly impacted by social support. Perhaps other variables not included in the model, such as skills acquisition and motivational factors, more directly impact self-efficacy. Furthermore, although we created a latent variable that combined depressive symptomatology, anxiety, and stress, the data on their unique associations with adherence are mixed; future investigators should examine them individually and combine them only if, as in this study, their intercorrelations are high. Because this model differs from the one we proposed, it is presented as preliminary and requiring further validation.

The model accounted for a relatively minor amount of variance (8%) in both adherence and viral load. Assessing social support that is specific to the particular illness or treatment regimen under study (as we did with the informational support items) rather than using a general measure of support might result in stronger associations between social support and adherence (Darbes & Lewis, 2006). Additionally, future models could include tangible support, another type of functional social support that may affect adherence through medication access or availability. Finally, an adequate predictive model of social support should consider a range of individual differences in need or desire for support as well as the social and environmental contexts of support giving (Cohen & Syme, 1985).

Findings from the bivariate analyses of the adherence measures involving substance use, side effects, and social desirability generally contradict findings of prior studies. For example, adherence did not differ by class of medication, despite protease inhibitors’ contributing to the majority of side effects experienced by persons on ART, or by regimen complexity, despite previous research showing that adherence declines as the number of daily doses increases (Stone et al., 2001). The majority (85%) of participants in our study were on twice daily regimens, however, and the limited variance may have prevented us from detecting a difference. Overall, our substance use indicators failed to predict adherence, as has been the case with some, but not all, studies examining these variables (Bangsberg et al., 2000; Ickovics & Meisler, 1997; Remien et al., 2003; J. S. Tucker et al., 2004). Past drug or alcohol use may not correlate with current adherence levels, but current heavy drug or alcohol use, creating a chaotic lifestyle, could impact adherence. More sensitive measures of substance use may be needed to tap this relationship. In our analysis, the presence of side effects did not appear to impact adherence. However, the somewhat low mean side effect intensity score reported by this group (i.e., 1.28 out of possible 4) and the large percentage of persons already well established on their ART regimens led to relatively low variance in side effect intensity scores, decreasing the likelihood of our detecting a relationship between side effects and adherence. Side effect intensity may vary over time on medications but is often worst at initiation of therapy. Prospective and longitudinal observation of side effects and adherence following medication initiation may be necessary to disentangle the relationship between the presence of side effects and adherence. The lack of association between the adherence measures and social desirability lends some support to the validity of self-reports as a method of assessing adherence.

In addition to theory building, our findings have implications for intervention development and clinical practice. They suggest that the social support received from an affirming other, an information-enhancing relationship, an empathic listener, or a spiritual relationship (i.e., the types of support assessed with our instrument) is associated with improved medication adherence. Consequently, adherence may be improved through future efforts to improve individuals’ access to social support, whether by encouraging them when safe and appropriate to confide in a partner or close friend or by facilitating their relationships with their medical care providers or with peers who are on similar medication regimens (Cohen, Underwood, & Gottlieb, 2000; Uchino, 2004). Interventions designed to increase the social support available to individuals are needed to explore the feasibility and efficacy of manipulating support provided to enhance adherence.

Additionally, the findings suggest that enhancing social support mediators (i.e., greater self-efficacy to adhere and spirituality and decreased negative affect) may improve adherence. Bandura (1997) suggested that individual self-efficacy is based on four sources of information (i.e., one’s own previous experiences, watching others perform a given behavior, verbal persuasion, and emotional arousal), any of which might be targeted to enhance self-efficacy to adhere. His data also suggested that lasting changes in self-efficacy and behavior can be achieved by initially using powerful behavior-altering methods, then removing the external prompts to verify self-efficacy, and finally encouraging mastery of the new skill (Bandura, Jeffery, & Gajdos, 1975). With respect to negative affect, our findings support a psychological assessment prior to initiation of therapy and during maintenance treatment so that strategies for treating depression and anxiety and minimizing stress can be incorporated into the care plan before adherence is negatively impacted. For spiritually inclined individuals, interventions focused on spiritual coping that could help to maintain a positive attitude and motivation toward health should be explored further. Such interventions could fill a culturally significant need for support (Jenkins & Pargament, 1995). Although we could not examine the effect of knowledge in our model, prior research has suggested that it is at least a necessary, if not sufficient, factor in adherence and should be addressed. Information about specific medications, adherence strategies, the importance of adherence, and the management of side effects needs to be communicated throughout the course of treatment and not just at initiation.

Interventions for HIV-positive persons on ART are especially needed (Simoni, Frick, Pantalone, & Turner, 2003). Given the lingering stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS, even in high-prevalence areas such as the Bronx, social support may be especially important for persons on ART. Low-income patients of ethnic minority status, who constituted the majority of participants in our study, may be especially vulnerable to the added daily burden of HIV disease and its stigma and be particularly in need of support if they are more prone to depression, anxiety, and stress. They may be amenable to novel interventions, such as the Web-based interactive system designed for depressed African American women (Lai, Jenkins, & Bakken, 2004). Tangible support or material assistance in the form of getting a ride to the clinic or picking up medications, although not examined in this preliminary study, might also facilitate adherence among those with few resources.

Future research is needed to validate this preliminary model, perhaps on larger and demographically different samples and with respect to different chronic illness regimens. Only with a sound theoretical model can the pervasive problem of medication adherence among individuals with chronic illness be understood and effective interventions then be devised to assist them.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 1 R01 MH58986 to Jane M. Simoni. We appreciate the assistance of Laura Bauman, who helped to conceptualize the original model, and Irwin Sarason, who made helpful comments on drafts of this article.

Contributor Information

Jane M. Simoni, Department of Psychology, University of Washington

Pamela A. Frick, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Washington

Bu Huang, School of Social Work, University of Washington.

References

- Albrecht TL, Adelman MB. Communicating social support. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Chang CJ, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: Comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clinical Infectious Disease. 2001;33:1417–1423. doi: 10.1086/323201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1997;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Jeffery RW, Gajdos E. Generalizing change through participant modeling with self-directed mastery. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1975;13:141–152. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(75)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14:357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, Moss A. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15:1181–1183. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JA. Addressing the challenges of adherence. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;29(Suppl. 1):S2–S10. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200202011-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH, Maiman LA. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance. Journal of Community Health. 1980;6:113–135. doi: 10.1007/BF01318980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besch CL. Compliance in clinical trials. AIDS. 1995;9:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bozette SA. Derivation and properties of a brief health-related quality-of-life assessment instrument for use in HIV disease. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1995;8:253–265. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan RD, Harrison RV, Wellons RV, Frech JRP. Social support and patient adherence: Experimental and survey findings. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Survey Research Center; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychology. 2000;19:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwicki B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Syme SL. Social support and health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Connor AP, Wicker CA, Germino BB. Understanding the cancer patient’s search for meaning. Cancer Nursing. 1990;13:167–175. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL. How often is medication taken as prescribed? JAMA. 1989;261:3273–3277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne D, Marlow D. The approval motive: Studies in evaluative dependence. New York: Wiley; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Darbes LA, Lewis MA. HIV-specific social support predicts less sexual risk behavior in gay male couples. Health Psychology. 2006;24:617–622. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG, Smith M, Holodniy M, Kahn JO. HIV-1 protease inhibitors: A review for clinicians. JAMA. 1997;277:145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Klerk E, van der Linden S. Compliance monitoring of NSAID drug therapy in ankylosing spondylitis, experiences with an electronic monitoring device. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1996;35:60–65. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, DiNicola DD. Achieving patient compliance: The psychology of the medical practitioner’s role. New York: Pergamon Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Schrott HG, Metcalf L, Iasiello-Vailas L. Effect of spouse support and health beliefs on medication adherence. Journal of Family Practice. 1983;17:837–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp JAL. The effects of social support and health professional home visits on patient adherence to hypertension regiments. Preventive Medicine. 1979;8:155. [Google Scholar]

- Eldred LJ, Wu AW, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Adherence to antiretroviral and pneumocystis prophylaxis in HIV disease. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1998;18:117–125. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199806010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson S, Ascione F, Kirking D, Johnson C. Use of a paging system to improve medication self-management in patients with asthma. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 1998;38:767–769. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland GH, Williams A. Attaining higher goals in HIV treatment: The central importance of adherence. AIDS. 1999;13(Suppl. 1):S61–S72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JE, Block DS. Adherence to antiretroviral regimens in HIV-infected patients: Results of a survey among physicians and patients. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 1998;4(5):32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geest SD, Borgermans L, Gemoets H, Abraham I, Vlaminck H, Evers G, Vanrenterghem Y. Incidence, determinants, and consequences of subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1995;59:340–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford AL, Bormann JE, Shively MJ, Wright BC, Richman DD, Bozzette SA. Predictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimens. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;23:386–395. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Duran RE, McPherson-Baker S, Ironson G, et al. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 2004;23:413–418. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo V, Amo JD, Soriano V, Gonzalez-Lahoz J. Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:1763–1769. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes RB. Introduction. In: Haynes RB, Sackett DL, editors. Compliance in health care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 1979. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes RB, McKibbon K, Kanani R. Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet. 1996;348:383–386. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RS, Heath KV, Yip B, Craib KJP, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, Mantaner JSG. Improved survival among HIV-infected individuals following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 1998;279:450–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.6.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, Gronert MK, Sison A, Lederberg M, et al. A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:460–469. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<460::AID-PON328>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer W, Corless I, Nokes K, Turner J, Brown M, Powell-Cope G, et al. Predictors of self-reported adherence in persons living with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 1999;13:185–197. doi: 10.1089/apc.1999.13.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Kahn RL. Measures and concepts of social support. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Meisler AW. Adherence in AIDS clinical trials: A framework for clinical research and clinical care. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilfeld FW. Further validation of a psychiatric symptom index in a normal population. Psychological Reports. 1976;39:1215–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins RA. Religion and HIV: Implications for research and intervention. Journal of Social Issues. 1995;51:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins RA, Pargament KI. Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. In: Somerfield MR, editor. Psychosocial resource variables in cancer studies: Conceptual and measurement issues. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 1995. pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Morin SF, Charlebois E, et al. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: Findings from the Healthy Living Project. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:645–656. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, Rabeneck L, Zackin R, Sinclair G, et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54(Suppl. 1):S77–S90. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski JM. Spiritual well-being and anxiety in adults diagnosed with cancer. Hospice Journal. 1989;5:105–115. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1989.11882658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM, Toshima MT. Adherence to prescribed regimens for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In: Shumaker SA, Schron EB, editors. The handbook of health behavior change. New York: Springer; 1990. pp. 126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kirscht JP, Kirscht JL, Rosenstock IM. A test of interventions to increase adherence to hypertensive medical regimens. Health Education and Behavior. 1981;8:261–272. doi: 10.1177/109019818100800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T, Jenkins M, Bakken S. Tailoring intervention for depressive symptoms in HIV-infected African American women. Med-info. 2004;20:1705. [Google Scholar]

- Low-Beer S, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS, Montaner JSG. Adherence to triple therapy and viral load response. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;23:360–361. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Moore RD, Graham NMH. Potential factors affecting adherence with HIV therapy. AIDS. 1997;11:1665–1670. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199714000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D, Turk D. Facilitating treatment adherence: A practitioner’s guidebook. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Levine DM, Green LW, Shapiro S, Russell RP, Smith CR. Five-year blood pressure control and mortality following health education for hypertensive patients. American Journal of Public Health. 1983;73:153–162. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD. What structural modeling techniques can tell us about social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR, editors. Social support: An interactional view. New York: Wiley; 1990. pp. 26–63. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD. Drug use and intimate relationships among women and men: Separating specific from general effects in prospective data using structural equation models. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:463–476. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkerk PT, Sprangers MA, Burger DM, Hoetelmans RM, Hugen PW, Danner SA, et al. Limited patient adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection in an observational cohort study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161:1962–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn TC, Brookmeyer R, Kline R, Shepherd M, Paranjape R, Mehendale S, et al. Feasibility of pooling sera for HIV-1 viral RNA to diagnose acute primary HIV-1 infection and estimate HIV incidence. AIDS. 2000;14:2751–2757. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200012010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Wagner G, Dolezal C, Carballo-Dieguez A. Levels and correlates of psychological distress in male couples of mixed HIV status. AIDS Care. 2003;15:525–538. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000134764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KJ. Barriers to and facilitators of HIV-positive patients’ adherence to antiretroviral treatment regimens. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2000;14:155–168. doi: 10.1089/108729100317948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. Patients’ compliance with health regimens. JAMA. 1975;234:402–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon H, Wainberg MA, Brenner B, Quan Y, Rouleau D, Cote P, et al. Prevalence of HIV-1 resistant to antiretroviral drugs in 81 individuals newly infected by sexual contact or injecting drug use. Investigators of the Quebec Primary Infection Study. AIDS. 2000;14(2):F17–F23. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg SS. Struggling for meaning: How HIV-positive gay men make sense of AIDS. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1993;24:483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Dunkel-Schetter C, Kemeny M. The multidimensional nature of received social support in gay men at risk of HIV infection and AIDS. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22:319–339. doi: 10.1007/BF02506869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Frick PA, Lockhart D, Liebovitz D. Mediators of social support and antiretroviral adherence among an indigent population in New York. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2002;16:431–439. doi: 10.1089/108729102760330272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, Turner BJ. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: A review of current literature and ongoing studies. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2003;11(6):185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kerwin JF, Martone MM. Spirituality and psychological adaptation among women with HIV/AIDS: Implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Berman SM, Swindells S, Justis JC, Mohr JA, Squier C, Wagener MM. Adherence of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients to antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Disease. 1999;29:824–830. doi: 10.1086/520443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Squier C, Sivek C, Wagener M, Nguyen MH, Yu VL. Determinants of compliance with antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: Prospective assessment with implications for enhancing compliance. AIDS Care. 1996;8:261–269. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Kirking DM, ACSUS (AIDS Costs and Services Utilization Survey) The effect of insurance coverage changes on drug utilization in HIV disease. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;28:140–149. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200110010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone VE, Hogan JW, Schuman P, Rompalo AM, Howard AA, Korkontzelou C, et al. Antiretroviral regimen complexity, self-reported adherence, and HIV patients’ understanding of their regimens: Survey of women in the HERS study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;28:124–131. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200110010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman GJ, Angelina AF, Hutton HE. Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with HIV infection. JAMA. 2001;286:2857–2864. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Orlando M, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Psychosocial mediators of antiretroviral non-adherence in HIV-positive adults with substance use and mental health problems. Health Psychology. 2004;23:363–370. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;35:417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti WM. Treatment adherence improves outcomes and manages costs. AIDS Reader. 2001;11(2):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiel HOF, Baumann U. The meaning and measurement of social support. New York: Hemisphere Publication Services; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ, Remien RH, Carballo-Dieguez A, Dolezal C. Correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among members of HIV-positive mixed status couples. AIDS Care. 2002;14:105–109. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Llabre MM, Durán RE, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Penedo FJ, Schneiderman N. A stress and coping model of medication adherence and viral load in HIV-positive men and women on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Health Psychology. 2005;24:385–392. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Basic processes in helping relationships. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Fegan MF. Social networks and social support. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer BJ, Pargament KI, Cole B, Rye MS, Belavich TG, Hipp KM, et al. Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997;36:549–564. [Google Scholar]