Structured Summary

Background

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a necessary condition to the improvement of HIV patient health and public health through ART. This study sought to determine the comparative effectiveness of different interventions for improving ART adherence among HIV-infected persons living in Africa.

Methods

We searched for randomized trials that evaluated an intervention to promote antiretroviral adherence within Africa. We created a network of the differing interventions by pooling the published and individual patient data for comparable treatments and comparing them across the individual interventions using Bayesian network meta-analyses. Outcomes included self-reported adherence and viral suppression.

Findings

We obtained data on 14 randomized controlled trials, involving 7,110 patients. Interventions included daily and weekly short message service (SMS) messaging, calendars, peer supporters, alarms, counseling, and basic and enhanced standard of care (SOC). For self-reported adherence, we found distinguishable improvement in adherence compared to SOC with enhanced SOC (odds ratio [OR]: 1.46, 95% credibility interval [CrI]: 1.06–1.98), weekly SMS messages (OR:1.65; 95% CrI: 1.25–2.18), counseling and SMS combined (OR:2.07; 95% CrI: 1.22–3.53), and treatment supporters (OR:1.83; 95% CrI:1.36–2.45). We found no compelling evidence for the remaining interventions. Results were similar when using viral suppression as an outcome, although the network of evidence was sparser. Treatment supporters with enhanced SOC (OR:1.46; 95% CrI: 1.09–1.97) and weekly SMS messages (OR:1.55; 95% CrI: 1.00–2.39) were significantly superior to basic SOC.

Interpretation

Several recommendations for improving adherence are unsupported by the available evidence. These findings should influence guidance documents on improving ART adherence in poor settings.

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has clinical and public health benefits by decreasing morbidity and mortality of HIV-infected individuals as well as HIV transmission to sex partners.1 Many patients experience difficulties in taking their ART at some time in their life and may take it only sporadically or take drug holidays.2 There are many possible reasons for not taking ART, including a myriad of social, personal and structural factors.3, 4 Promoting adherence to ART is considered one of the chief public health concerns for populations living with HIV infection.5

Despite the importance of achieving and maintaining high rates of ART adherence, few interventions have proved successful among those experiencing difficulties.6, 7 In Africa, where most people with HIV infection reside, there are specific social, structural or health system-related barriers that are particularly prevalent including food insecurity, stigma, supply chain interruptions, and a lack of human health resources.8 Previous systematic reviews have identified potentially effective interventions, but have not evaluated their effectiveness in a statistical way.7, 9, 10

The past decade has seen important progress in the field of evidence synthesis, particularly with the popularization of network meta-analysis (NMA).11–14 In traditional meta-analysis, all included studies compare the same intervention with the same comparator. NMA extends this concept by including multiple pairwise comparisons across a range of interventions and provides estimates of relative treatment effects on multiple treatment comparisons for comparative effectiveness purposes based on direct and/or indirect evidence. Here, direct evidence for the effect of treatment B vs. A would correspond to the evidence familiar to us in pairwise meta-analysis, combining all head to head comparisons. Indirect evidence corresponds to all common comparisons of B vs. A through common comparators, such as standard of care. Thus, NMA allows for inference between two interventions even in the absence of head-to-head evidence. The conditions required for conducting these analyses resemble those of traditional meta-analysis, however, they require that direct and indirect evidence be in agreement, a condition called consistency. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate what ART adherence interventions have been conducted in the African setting. We used a NMA approach to draw from both direct and indirect evidence from randomized trials.

METHODS

This study has been designed and reported according to the pending Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) extension to network meta-analyses.15 The protocol for this study is available from the authors upon request.

Selection Criteria

The populations, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study designs considered for review are listed in Box 1. All RCTs must have included an intervention targeted to increase ART adherence, and targeted to increase ART adherence over a minimum of a 3-month period, and report ART adherence as an outcome. We restricted trials to African countries to avoid issues of dissimilarity that arise from variations in HIV risk groups.

Box 1.

Population, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study design (PICOS) criteria for study inclusion.

| Criteria | Definition |

| Population | Adult HIV+ patients on ART in Africa |

| Interventions | Any intervention to improve adherence to ART |

| Comparisons | Standard of care or another intervention to improve adherence to ART |

| Outcomes | Any measurement of adherence to ART |

| Study Design | RCT with minimum 3 months of follow-up |

| Treatment definitions used for categorization of interventions in the network meta-analysis | |

| Criteria | Definition |

|

Standard of Care (SOC) |

Usual standard of care |

|

Enhanced SOC (eSOC) |

Usual standard of care, plus intensified adherence counseling |

| Alarm | Participants received a pocket alarm device which they were to carry around at all times; this device was programmed to beep and flash twice a day to remind patients to take their medication |

| eSOC + alarm | Enhanced SOC plus the pocket alarm device as described above |

| eSOC + calendar | In addition to enhanced SOC, patients were given a treatment calendar containing educational messages about ART and adherence; patients were to record when they took their medication in the calendar |

| Daily SMS | Daily text message sent to the patient’s cell phone (their own or one provided by the study) – with or without ability for patient to respond to care provider |

| Weekly SMS | Weekly text message sent to the patient’s cell phone (their own or one provided by the study) – with or without ability for patient to respond to care provider |

| eSOC + weekly SMS | Weekly text message sent to the patient’s cell phone (their own or one provided by the study) in addition to enhanced SOC |

|

eSOC + treatment supporter |

Treatment supporter (chosen by individual or assigned by clinic) in addition to enhanced SOC |

|

SOC + treatment supporter |

Treatment supporter (chosen by individual or assigned by clinic) in addition to SOC |

Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic search of the medical literature for relevant randomized clinical trials that described interventions to improve adherence to ART among HIV-positive patients, using terms for “HIV”, “ART”, “adherence” and “Africa”. The search was conducted using the following electronic databases: AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE (via PubMed), and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to October 2014. The complete search strategy used to identify studies is available in the web appendix. Two investigators (KM, ML) reviewed all abstracts and full-text articles. We contacted all study authors and requested the individual data on patients achieving adherence and viral suppression. We did not set any restriction based on publication date and included all studies available as of October 2014.

Data extraction and Variable Definitions

Using a standard data sheet, we extracted the following data from articles that met the inclusion criteria: 1) trial duration; 2) trial location; 3) year of publication; 4) rate of loss to follow-up; 5) ART experience; 6) proportion of women; 7) median age; 8) sample size within each treatment arm; 9) treatment within each arm; 10) count of participants attaining adherence in each arm; 11) the measures of adherence used; 12) the number retained throughout the study. When data were unavailable or only partial, we requested data directly from authors. Data extraction from eligible studies was done independently and in duplicate.

We grouped treatment arms using the following categories: 1) standard of care (SOC); 2) enhanced standard of care (eSOC); 3) alarm; 4) eSOC + alarm; 5) eSOC + calendar; 6) daily SMS; 7) weekly SMS; 8) eSOC + weekly SMS; 9) eSOC + treatment supporter; 10) SOC + treatment supporter. Definitions for treatment groupings are provided in Box 1. In brief, SOC consisted of regular ART pick-ups including consultations with physician or pharmacist. In some cases adherence counseling was reported as part of SOC, and in others as a specific intervention, particularly when counselors were involved. We did not differentiate such cases and considered interventions that included adherence counseling in addition to SOC, either directly from the health practitioner or from adherence counselors, to be eSOC. Finally, we did not differentiate treatment supporters that assisted in directly observed treatment (DOT) and those who provided other assistance.

The primary outcome was adherence as defined by the proportion of patients in each RCT arm meeting the trial-defined adherence criteria. Adherence was measured using the percentage of pills taken with various cut-off values and when multiple measures were reported they were favored in the following order: 95%, 90%, 80%, and 100%. We chose to place the 100% cut-off last in our order because it over-estimates poor adherence.16 The proportion of patients achieving viral suppression was collected as a secondary outcome. All outcomes were extracted at the end of study period.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

To inform comparative effectiveness between all interventions, we conducted a Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA) using all ten intervention types.17 This method provides better comparative evidence than pair-wise meta-analysis because it combines direct (i.e., head-to-head comparisons) and indirect evidence (comparisons across a common comparator) and in doing so increases the power of statistical comparisons while allowing for inferences of comparative effects between interventions that have not been compared head-to-head.13, 18 In estimating the efficacy parameters using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, we used a burn-in of 20,000 iterations and 40,000 iterations for estimation. Convergence was assessed used Gelman-Rubin diagnostics. Priors were normally distributed, centered at zero, with large variance for all parameters except the probability of adherence and viral suppression, which both used a binomial prior distribution.

We performed edge-splitting to assess the consistency of direct and indirect evidence for interventions for which both types of information was available.19 We assessed the deviance information criterion (DIC) as a measure of model fit that penalizes for model complexity.20 We modeled comparative log odds ratios using the conventional logistic regression NMA setup.17 All results for the network meta-analysis are reported as posterior medians with corresponding 95% credibility intervals (CrIs), the Bayesian analog of classical confidence intervals. Sensitivity analyses included period of trial follow-up and choices of adherence thresholds for measurement.

All analyses were conducted using WinBUGS version 1.4 (Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge) and R version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org/).

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

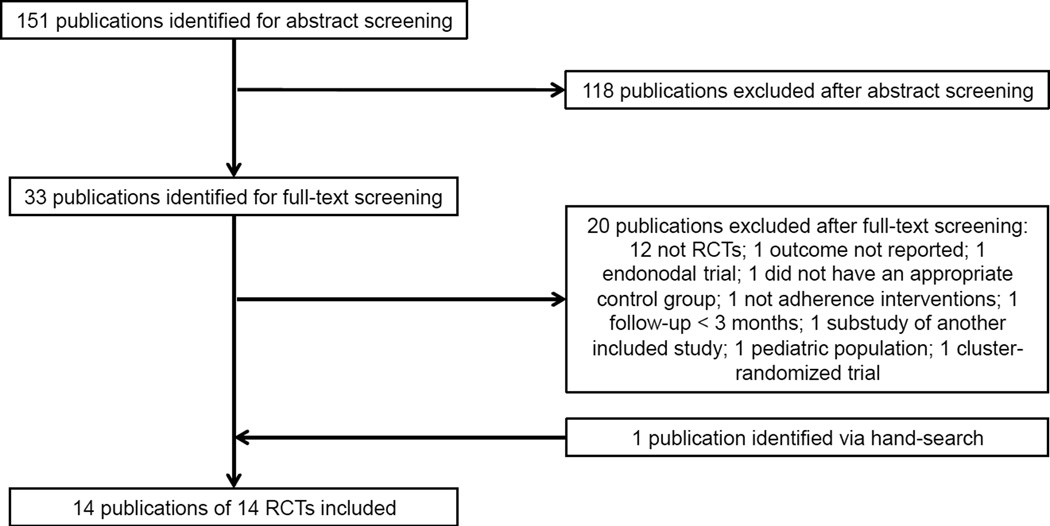

We identified 151 relevant abstracts (Figure 1). Of these, 118 publications did not meet our inclusion criteria. Of the 33 further reviewed manuscripts, we excluded 20 publications (as not RCTs [n=12],21–32 not adherence interventions [n=1],33 did not report adherence after 3 months [n=1],34 irrelevant interventions [n=2],35, 36 outcome not reported [n=1],37 cluster study design [n=1],38 paediatric population [n=1],39 or sub-study of another included trial [n=1]40); these studies are listed in Appendix 2. We included the remaining 13 publications, along with an additional poster provided following the search. Together, these described 14 RCTs in our analyses (Table 1).38, 39, 41–53 Individual level data were available for 9 of the RCTs.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of included trials reporting on adherence interventions for HIV-positive patients on ART

| Trial | Trial location |

Trial duration |

Measures of adherence | Comparisons | Age | % Women |

N patients | N adherent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang, 2010 | Uganda | 192 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence; 100% adherence; no missed dose (self- report) |

eSOC | 34.0 (17–70)a | 66% | 366 | 322/253/265 |

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 35.5 (15–76) | 970 | 862/651/716 | |||||

| Chung, 2011 | Kenya | 78 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence | SOC | 35 (30–40)a | 71% | 100 | 51 |

| eSOC | 36 (31–44) | 59% | 100 | 52 | ||||

| Alarm | 36 (32–41) | 68% | 100 | 47 | ||||

| eSOC + alarm | 38 (32–44) | 66% | 100 | 58 | ||||

| Gross, 2014 | Brazil, Botswana, Haiti, Peru, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe |

48 weeks | % doses taken (not used in adherence analysis) |

SOC | 37 (33–45)e | 51% | 128 | NR |

| SOC + treatment supporter | 38 (34–44) | 48% | 129 | NR | ||||

| Kunutsor, 2011 | Uganda | 28 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence | eSOC | 39.2 (8.4)b | 66% | 87 | 71 |

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 39.1 (8.3) | 71% | 87 | 80 | ||||

| Lester, 2010 | Kenya | 26–52 weeks |

≥ 95% adherence | SOC | 36.7 (19–65)c | 66% | 265 | 132 |

| Weekly SMS | 36.6 (22–84) | 65% | 273 | 168 | ||||

| Maduka, 2012 | Nigeria | 17 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence | SOC | 35.3 (9.0)b | 56% | 52 | 29 |

| eSOC + weekly SMS | 36.6 (11.8) | 44% | 52 | 40 | ||||

|

Mbuagbaw, 2012 |

Cameroon | 26 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence, no missed dose (self-report) |

eSOC | 39.0 (10.0)b | 79% | 99 | 66/78 |

| eSOC + weekly SMS | 41.3 (10.1) | 68% | 101 | 72/80 | ||||

| Mugusi, 2009 | Tanzania | 52 weeks | No missed dose (self-report) | eSOC | 39.9 (8.8)b | 69% | 312 | 294 |

| eSOC + calendar | 39.5 (8.7) | 61% | 242 | 229 | ||||

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 37.8 (14.6) | 58% | 67 | 64 | ||||

| Nachega, 2010 | South Africa | 104 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence | SOC | 35.7 (9.7)b | 58% | 137 | 120 |

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 36.7 (9.2) | 58% | 137 | 126 | ||||

| Peltzer, 2012 | South Africa | 17 weeks | No missed dose (self- report) |

SOC | 37.1 (9.8)b | 61% | 76 | 65 |

| eSOC | 36.6 (9.4) | 70% | 76 | 71 | ||||

| Pearson, 2007 | Mozambique | 52 weeks | 100% adherence | eSOC | 35.6d | 53% | 175 | 143 |

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 36.1 | 54% | 175 | 151 | ||||

|

Pop-Eleches, 2011 |

Kenya | 48 weeks | ≥ 90% adherence | SOC | 35.6 | 66% | 139 | 55 |

| Daily SMS | 35.7 | 68% | 142 | 59 | ||||

| Weekly SMS | 37.3 | 64% | 147 | 78 | ||||

| Sarna, 2008 | Kenya | 72 weeks | ≥ 95% adherence | eSOC | 37 (7.8)b | 64% | 118 | 85 |

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 37.3 (8.0) | 64% | 116 | 75 | ||||

| Taiwo, 2010 | Nigeria | 24 weeks* | ≥ 95% adherence | SOC | 34.2 (8.9) | 63% | 251 | 181 |

| eSOC + treatment supporter | 66% | 248 | 220 | |||||

The duration of this trial was 48 weeks. Results at 24 weeks were used because after 24 weeks the SOC arm was switched to eSOC.

Median (range);

Mean(standard deviation);

Mean(range);

Mean;

Median(interquartile range);

SOC: standard of care; eSOC: enhanced standard of care.

Adherence

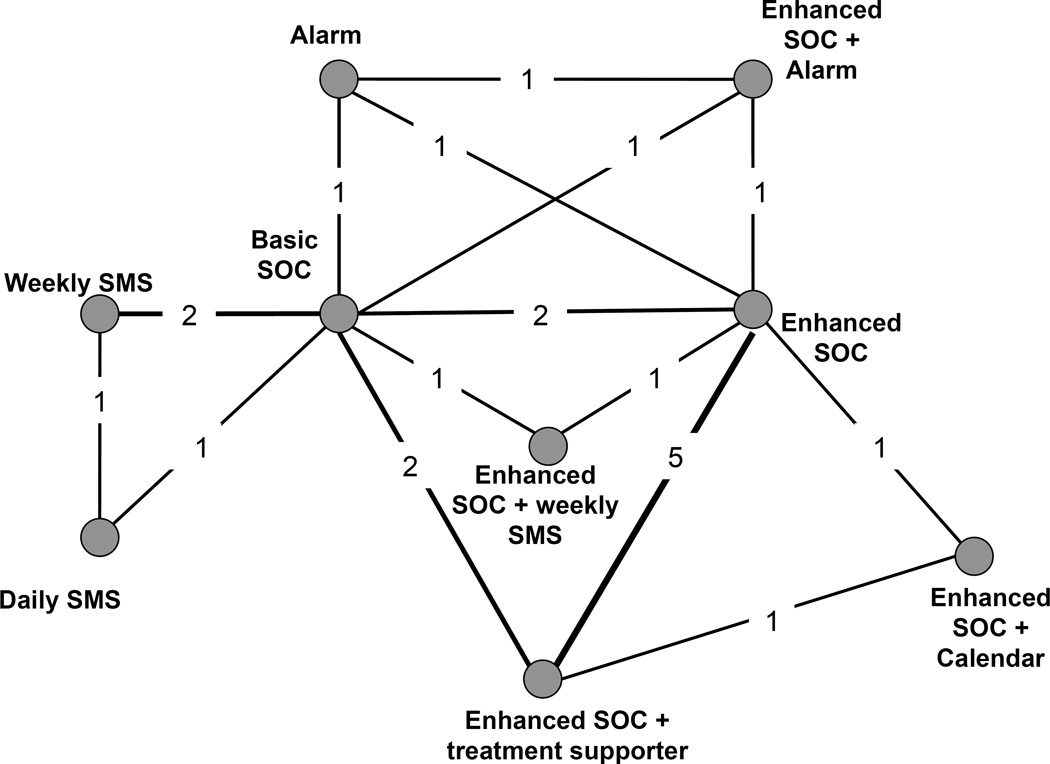

Our primary network includes data from 13 studies (n = 5,310), comprising 30 treatment arms. Figure 2 represents the network of evidence for ART adherence interventions contained in the included studies. Nodes represent each included intervention; numbers on each edge represent the number of corresponding trials. Follow-up time for adherence outcomes varied from 17 to 192 weeks. Various measures were used to report adherence. The most common measure reported was the proportion of patients in each arm with at least 95% adherence by self-report; ten studies reported this operationalization.41–46, 48, 51–53 Four studies reported the proportion of patients with no missed dose or 100% adherence,41, 46, 47, 53 and two reported the proportion with at least 90% adherence.49, 50

Figure 2.

Network diagram for randomized clinical trials evaluating interventions seeking to improve ART adherence among HIV-positive patients

Legend. Nodes represent the individual or combined interventions. Lines between the nodes represent where direct (head-to-head) RCTs have been conducted. The numbers within those lines indicate the number of RCTs that have been conducted.

In order to assess consistency across the network, we calculated direct and indirect evidence for each comparison for which both types of evidence were available. The results of this edge-splitting exercise are presented in Appendix 3. Results were consistent between direct and indirect evidence, suggesting that conditions required for these analyses were met.

Table 2 presents odds ratios (OR) and 95% credibility intervals (CrI) for all pairwise comparisons of adherence interventions. Enhanced SOC performed better than basic SOC. Weekly SMS (with or without eSOC) was associated with better adherence than SOC alone. The combination of eSOC with a treatment supporter performed better than SOC, eSOC, or the alarm alone. Weekly SMS (without eSOC) was associated with higher adherence than daily SMS (OR 1.56, 95% CrI 1.01–2.40); the difference between weekly SMS with eSOC compared to daily SMS was not statistically or operationally important. No other pairs of adherence interventions were found to be statistically different. Further inference can be drawn from table 2. The combination of the effect estimates for eSOC and weekly SMS was 2.41, suggesting an additive effect of eSOC and weekly SMS.

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% credibility intervals for adherence to ART among HIV-positive patients

| SOC | eSOC | Alarm | eSOC + alarm |

eSOC + calendar |

Daily SMS | Weekly SMS |

eSOC + weekly SMS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSOC |

1.46 (1.06–1.98) |

|||||||

| Alarm | 1.00 (0.60–1.67) |

0.69 (0.41–1.14) |

||||||

| eSOC + alarm | 1.57 (0.94–2.62) |

1.08 (0.65–1.80) |

1.56 (0.89–2.74) |

|||||

| eSOC + calendar | 1.81 (0.91–3.96) |

1.25 (0.67–2.57) |

1.81 (0.82–4.36) |

1.16 (0.52–2.77) |

||||

| Daily SMS | 1.06 (0.68–1.64) |

0.73 (0.43–1.24) |

1.06 (0.54–2.07) |

0.68 (0.34–1.32) |

0.58 (0.24–1.32) |

|||

| Weekly SMS |

1.65 (1.25–2.18) |

1.14 (0.75–1.72) |

1.64 (0.93–2.94) |

1.05 (0.58–1.88) |

0.91 (0.40–1.92) |

1.56 (1.01–2.40) |

||

| eSOC + weekly SMS |

2.07 (1.22–3.53) |

1.42 (0.86–2.35) |

2.06 (1.03–4.11) |

1.32 (0.66–2.63) |

1.14 (0.47–2.52) |

1.95 (0.98–3.89) |

1.25 (0.69–2.29) |

|

|

eSOC + treatment supporter |

1.83 (1.36–2.45) |

1.26 (1.00–1.58) |

1.82 (1.08–3.10) |

1.17 (0.69–1.98) |

1.01 (0.48–1.93) |

1.73 (1.02–2.94) |

1.11 (0.74–1.67) |

0.88 (0.52–1.50) |

SOC: standard of care; eSOC: enhanced standard of care. An odds ratio greater than 1.00 indicates an estimated increased odds of adherence for the intervention along the vertical axis in the first column, whereas an odds ratio less than 1.00 indicates an estimated decreased odds of adherence for the regimen along the vertical axis in the first column. Bolded results indicate statistically significant relationship.

We additionally examined the follow-up time and choice of adherence measurement as potential sources of heterogeneity through sub-analyses. Neither factor was found to influence the comparative efficacy measurements. As a sensitivity analysis for the adherence outcome, an additional NMA was conducted using the number remaining in the study (per-protocol) rather than intention to treat; the results are given in Appendix 4. Comparisons of eSOC+alarm versus SOC, eSOC, and alarm alone were all found to be statistically significant in the per-protocol analysis, suggesting differential loss-to-follow up among these treatment arms. Appendix 5 displays the pairwise pooled estimates compared with the network estimates.

Viral suppression

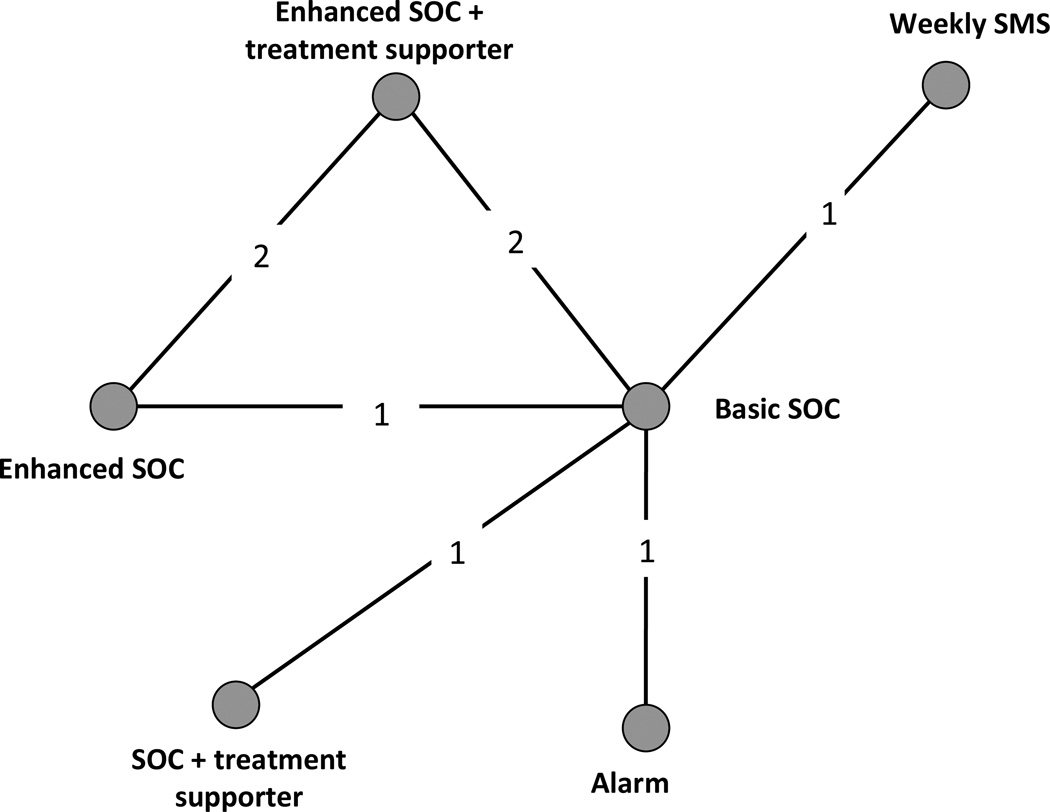

Our secondary network meta-analysis included data from 13 treatment arms in six studies41, 44, 48, 51, 52, 54 (N = 2,738). The network of evidence contained in these studies is shown in Figure 3. Six interventions were included in the studies with available viral suppression data: SOC, eSOC, alarm, weekly SMS, eSOC+treatment supporter, and SOC+treatment supporter. For studies where multiple time points were reported, the same time points were selected as in the adherence analysis where possible. Four studies reported the number of patients who had achieved plasma HIV RNA suppression (< 400 copies/mL),44, 51, 52, 54 one study reported the number of patients on-study with viral failure defined as ≥400 copies/mL,41, 54 and one study reported the number of patients on-study with viral failure defined as ≥5,000 copies/mL.42 We modeled viral suppression with an on-study analysis that treating measured lack of failure as equal to suppression regardless of the cutoff point.

Figure 3.

Network diagram for randomized clinical trials evaluating viral suppression between interventions seeking to improve ART adherence among HIV-positive patients.

Legend. Nodes represent the individual or combined interventions. Lines between the nodes represent where direct (head-to-head) RCTs have been conducted. The numbers within those lines indicate the number of RCTs that have been conducted.

As with adherence, we performed edge-splitting in order to assess consistency between direct and indirect evidence across the network. The results are shown in Appendix 6; results were reasonably consistent, although there was a greater (but still non-significant) OR found for eSOC vs SOC with direct evidence than by indirect evidence alone.

Table 3 presents ORs and 95% CrI for viral suppression for all pairwise comparisons of interventions with available viral suppression data. Both weekly SMS (OR: 1.55; 95% CrI: 1.01–2.38) and eSOC+treatment supporter (OR: 1.46; 95% CrI: 1.09–1.97) were associated with higher suppression rates than SOC, or SOC+treatment supporter. No other pairs of adherence interventions were found to be different with respect to viral suppression.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% credibility intervals - viral suppression (<400 copies/ml) at last reported time point.

| SOC | eSOC | Alarm | Weekly SMS |

eSOC + treatment supporter |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSOC | 1.32 (0.80–2.18) |

||||

| Alarm | 0.99 (0.51–1.93) |

0.75 (0.33–1.72) |

|||

| Weekly SMS |

1.55 (1.01–2.38) |

1.18 (0.61–2.25) |

1.57 (0.71–3.42) |

||

|

eSOC + treatment supporter |

1.46 (1.09–1.97) |

1.12 (0.71–1.73) |

1.48 (0.72–3.00) |

0.94 (0.56–1.60) |

|

|

SOC + treatment supporter |

0.61 (0.33, 1.11) |

0.46 (0.21, 1.00) |

0.62 (0.25, 1.49) |

0.39 (0.19, 0.83) |

0.42 (0.21, 0.81) |

SOC: standard of care; eSOC: enhanced standard of care.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis examined all RCTs conducted to evaluate interventions to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa. We found compelling evidence that enhanced standard of care improved patient adherence. This was further improved when combined with weekly SMS messages and treatment supporters. In fact, the combination of enhanced standard of care, a cognitive intervention, and weekly SMS messaging, a behavioral intervention, appeared to be additive in nature, a novel finding that could not be tested in the individual studies in the current evidence base. Our findings also provide evidence that there is insufficient evidence to support alarms, daily SMS messages, and calendars. These findings are at odds with some previous reports and meta-analyses and the difference may be partly explained by the analytical approach we used.10, 55 Our study found a large treatment benefit for weekly SMS messages but not for daily SMS messages. It is possible that there is a dose-effect wherein less is more as, supportive SMS messages may become a reminder when too frequent, and reminders do not appear to support adherence.56

Our findings have operational and clinical implications. For example, we found a large, additive treatment benefit of adding weekly SMS messages to enhanced standard of care. Our study suggests that combining cognitive and behavioural interventions could maximize the intervention efficacy. Although weekly SMS messaging is a relatively low cost intervention, it requires that patients have access to a cell phone and can receive SMS messages confidentially.57 Given the high penetration of mobile technology in low-income settings such as sub-Saharan Africa, India, etc. our findings may have global relevance and implications. Nonetheless, there remain features of the weekly SMS messaging intervention that need be further researched and determined by program managers, such as whether patients will be able to respond to the messages and reach a care provider (“two way” messages) or not (“one way”), and what content should be sent.58 The trials considered in this study differed in this regard.

Similarly, we found a large treatment effect of a treatment supporter in combination with enhanced standard of care. However, this intervention would be inappropriate where confiding one’s HIV status to another person is not possible.48 Our finding that treatment supporters importantly increase adherence is at odds with some reviews examining treatment supporters and directly observed therapy.55, 59 Other reviews have included populations with competing mental health concerns and have used standard meta-analysis approaches. The use of a network meta-analysis allows for greater power and greater precision in the analysis and this appears to explain why our findings are significant and other’s findings are not.60 Prior work has documented the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of treatment supporters as a community-based intervention (i.e. wide spread use of this method throughout the community).48, 61, 62

Across HIV programs, treatment supporters can be defined in several ways and this has created a debate within the implementation field as to what extent they should be promoted. Treatment supporters range from paid employees, such as accompagnateurs in Partners in Health projects, to unpaid family and friends in other programs.55 Similarly, treatment supporters may offer assistance that ranges from emotional support and reminding patients to adhere to therapy or more intensively offer services that may include directly observed therapy (DOT) and clinical monitoring. The evidence to support DOT is not convincing,55 but the evidence for social support that may include adherence discussions and reminders is much more broadly accepted. It is unlikely that this analysis will settle the issue.

There are several strengths and limitations to consider in our analysis. Strengths include our extensive search, communication with trialists, and the statistical approach we used. We held meetings of those working in the field to identify any additional trials and received individual patient level data where possible. Our statistical approach allows for greater power than standard meta-analysis as it incorporates data from both indirect and indirect evidence (see Appendix 4). Limitations of our review to generalizability include the lack of available data in specific populations such as HIV-infected children, adolescents, pregnant women, prisoners, MSM etc. that could be inserted into the network. We found a low number of studies for each individual intervention and so further confirmatory RCTs are warranted. We considered including studies from more developed settings, however, given that the HIV epidemic in Africa is substantially different than in other continents (in terms of a generalized epidemic) and that most RCTs in other settings have been directed at individuals with competing mental health concerns (e.g. addictions) or marginalized persons (e.g. homeless, youth, etc.), we believe that restricting the analysis to Africa is necessary to meet the conditions required for the methodology employed for our analyses.

An important limitation to our study pertains to treatment definitions. As opposed to drugs, these behavioral and cognitive interventions varied across studies. This is especially true of eSOC, defined as SOC with an educational component, because the education component varied according to content and whether it was delivered in-group or one-on-one. Nonetheless, statistical heterogeneity was moderate, suggesting that this was a minimal threat. Limitations to external validity include the exclusion of pediatric populations from the network, but this was by design given that adherence among children is typically a caregiver issue rather than patient-motivated. In addition, we considered various definitions of adherence and viral failure as equivalent. We considered self-reported adherence and more objective forms (such as medication event monitoring systems [MEMS]) as equivalent. However, self-report may over-estimate adherence.63 There were an insufficient number of studies to assess this using a sensitivity analysis. We included only RCTs and it is possible that there are other interventions that have been conducted at the program level in a non-research manner, that also have important treatment benefits. We are aware that interventions to promote retention in programs differ across and within countries and we acknowledge that some programs may use different adherence strategies also.64 Finally, we considered the RCT period as equivalent across studies and conducted a sensitivity analysis examining for duration of follow-up. Although we did not identify time as an effect modifier, it is likely that adherence will wane with any intervention over the long term.65, 66

Network meta-analysis should only be considered as valid as the individual comparisons within a network. In our network, several of the nodes in the network are informed by just one or two trials and at most by five trials. In general, the more trials in a comparison, the greater the power to detect treatment effects.18, 67 Although we cannot add trials to our network, because no other trials exist, we can assess whether the comparisons are believable by assessing the transitivity of direct versus indirect evidence.68 When we assessed pairwise estimates versus network estimates we found no evidence of inconsistency between the direct and indirect evidence. This increases our confidence that the network is sufficiently robust that the findings are unlikely to be spurious.68 As further evidence accumulates, this will further strengthen inferences from the network evaluation.

In conclusion, this study provides strong inferences that a standard of care that includes patient counseling on adherence, SMS messaging, and treatment supporters can improve adherence for patients residing in Africa. As the provision of ART in Africa becomes more long-term, sustainable efforts to promote adherence will be required. Future research should consider evaluating other novel adherence interventions individually or in combination, not only in adult populations but also in selected vulnerable populations where there is a large knowledge gap such as children, adolescents, and pregnant women, as well as assess the cost-effectiveness to inform policy-makers, clinicians and program managers.

Research in Context Panel.

Systematic Review

We conducted a systematic search of the medical literature for relevant randomized clinical trials that described interventions to improve adherence to ART among HIV-positive patients, using terms for “HIV”, “ART”, “adherence” and “Africa”. The search was conducted using the following electronic databases: AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE (via PubMed), and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to December 2013. We identified 14 RCTs for our analysis that met our study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Interpretation

We found compelling evidence that enhanced standard of care improved patient adherence. This was further improved when combined with weekly SMS messages and treatment supporters. As the provision of ART in Africa becomes increasingly available, effective interventions to promote adherence will be necessary to generate sustainable ART delivery.

Acknowledgments

Funding: No funding was received for this work.

Appendix 1

Search terms

(Human immunodeficiency virus OR HIV OR Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome OR AIDS OR HIV Infection[MeSH])

AND

(antiretroviral OR anti-retroviral OR antiretroviral therapy OR highly active antiretroviral therapy OR HAART OR Anti-HIV Agents OR Agents, Anti-HIV[MeSH])

AND

(patient compliance OR client compliance OR participant compliance OR adherence OR Adherence, Medication[MeSH] OR Therapy, Directly Observed[MeSH] OR Compliance, Patient[MeSH])

AND

(Algeria OR Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cameroon OR Cape Verde OR Central African Republic OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR Cote d'Ivoire OR Cote OR Democratic Republic of the Congo OR Equatorial Guinea OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Gabon OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Kenya OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Mauritius OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Rwanda OR Sao Tome and Principe OR Sao Tome OR Principe OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR Sierra Leone OR Somalia OR South Africa OR Swaziland OR Togo OR Uganda OR United Republic of Tanzania OR Tanzania OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR sub-saharan Africa OR subsaharan africa OR africa, sub-saharan OR Africa OR East Africa OR West Africa OR Southern Africa)

Appendix 2.

List of studies excluded following full-text review

| Study | Exclusion rationale |

|---|---|

| Byron, 200830 | Not an RCT |

| Cantrell, 200833 | Not an adherence intervention |

| Holstad, 201235 | Not an appropriate control group |

| Idoko, 200721 | Not an RCT |

| Igumbor, 201131 | Not an RCT |

| Kabore, 201022 | Not an RCT |

| Kiweewa, 201336 | Endonodal trial |

| Mansoor, 200634 | Follow-up less than 3 months |

| Munyao, 201040 | Substudy of Sarna51 |

| Pienaar, 200625 | Not an RCT |

| Pirkle, 200929 | Not an RCT |

| Rich, 201232 | Not an RCT |

| Roux, 200428 | Not an RCT |

| Sherr, 201023 | Not an RCT |

| Stubbs, 200924 | Not an RCT |

| Thurman, 201026 | Not an RCT |

| Torpey, 200827 | Not an RCT |

| Van Loggerenberg, 201037 | Adherence outcome not reported |

Legend: endonodal refers to a trial that compares a form of an intervention to another form of the same intervention (eg. dosing studies).

Appendix 3.

Direct versus indirect evidence for adherence to ART among HIV-positive patients, ITT analysis

| Indirect Effects | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | SOC | 1.46 (1.06, 2.00) |

1.00 (0.60, 1.68) |

1.57 (0.94, 2.61) |

1.06 (0.69, 1.63) |

1.65 (1.26, 2.17) |

2.07 (1.22, 3.53) |

1.83 (1.36, 2.47) |

|

| 1.23 (0.75, 1.73) |

eSOC | 0.69 (0.41, 1.15) |

1.08 (0.64, 1.82) |

1.08 (0.53, 2.25) |

1.42 (0.86, 2.35) |

1.26 (1.00, 1.58) |

|||

| 0.85 (0.49, 1.41) |

0.82 (0.47, 1.37) |

Alarm | 1.56 (0.89, 2.71) |

||||||

| 1.33 (0.76, 1.88) |

1.27 (0.73, 1.83) |

1.56 (0.89, 2.12) |

eSOC + alarm |

||||||

| 1.08 (0.52, 1.81) |

eSOC + calendar |

1.16 (0.54, 2.40) |

|||||||

| 1.09 (0.67, 1.56) |

Daily SMS | 1.56 (1.01, 2.40) |

|||||||

| 1.65 (1.25, 1.93) |

1.59 (1.00, 2.06) |

Weekly SMS |

|||||||

| 2.64 (1.13, 3.49) |

1.24 (0.68, 1.84) |

SOC + weekly SMS |

|||||||

| 1.89 (1.32, 2.26) |

1.23 (0.96, 1.48) |

1.21 (0.33, 2.50) |

eSOC + supporter |

||||||

Note: Each cell represents the comparison (odds ratio and 95% CrI) of the row treatment versus the column treatment below the diagonal and of the column treatment versus the row treatment above the diagonal.

Appendix 4.

Odds ratios and 95% credibility intervals for adherence to ART among HIV-positive patients, per-protocol analysis

| Standard of Care (SOC) |

Enhanced SOC |

Alarm | Enhanced SOC + alarm |

Enhanced SOC + calendar |

Daily SMS | Weekly SMS |

Enhanced SOC + weekly SMS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced SOC | 1.31 (0.93–1.85) |

|||||||

| Alarm | 0.97 (0.54–1.75) |

0.74 (0.41–1.34) |

||||||

|

Enhanced SOC + alarm |

2.92 (1.47–6.04) |

2.22 (1.09–4.64) |

3.00 (1.42–6.54) |

|||||

|

Enhanced SOC + calendar |

1.52 (0.68–3.51) |

1.15 (0.55–2.50) |

1.56 (0.61–4.18) |

0.52 (0.19–1.49) |

||||

| Daily SMS | 1.10 (0.69–1.74) |

0.84 (0.47–1.47) |

1.12 (0.54–2.38) |

0.38 (0.16–0.86) |

0.72 (0.28–1.83) |

|||

| Weekly SMS |

1.73 (1.31–2.30) |

1.32 (0.85–2.06) |

1.78 (0.93–3.44) |

0.59 (0.27–1.25) |

1.14 (0.47–2.65) |

1.58 (1.00–2.51) |

||

|

Enhanced SOC + weekly SMS |

1.94 (1.13–3.35) |

1.47 (0.89–2.45) |

1.98 (0.95–4.26) |

0.66 (0.28–1.53) |

1.27 (0.51–3.08) |

1.76 (0.87–3.58) |

1.12 (0.61–2.06) |

|

|

Enhanced SOC + treatment supporter |

2.10 (1.54–2.86) |

1.59 (1.19–2.15) |

2.15 (1.15–3.99) |

0.72 (0.33–1.47) |

1.38 (0.62–3.01) |

1.91 (1.10–3.35) |

1.21 (0.80–1.85) |

1.08 (0.62–1.87) |

An odds ratio greater than 1.00 indicates an estimated increased odds of adherence for the intervention along the vertical axis in the first column, whereas an odds ratio less than 1.00 indicates an estimated decreased odds of adherence for the regimen along the vertical axis in the first column. Bolded results indicate statistically significant relationships.

Appendix 5.

Results of pairwise meta-analyses of comparisons of adherence interventions

| Pairwise comparison | Network meta-analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | N Arms | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Enhanced SOC vs SOC | 2 | 1.24 (0.76–2.03) | 1.46 (1.06–1.98) |

| Alarm vs SOC | 1 | 0.85 (0.49–1.48) | 1.00 (0.60–1.67) |

| Enhanced SOC + alarm vs SOC | 1 | 1.33 (0.76–2.32) | 1.57 (0.94–2.62) |

| Daily SMS vs SOC | 1 | 1.89 (0.67–1.75) | 1.06 (0.68–1.64) |

| Weekly SMS vs SOC | 2 | 1.65 (1.15–2.28) | 1.65 (1.25–2.18) |

| Enhanced SOC + weekly SMS vs SOC | 1 | 2.64 (1.13–6.16) | 2.07 (1.22–3.53) |

| Enhanced SOC + treatment supporter vs SOC | 2 | 2.58 (1.71–3.89) | 1.83 (1.36–2.45) |

| Alarm vs enhanced SOC | 1 | 0.82 (0.47–1.43) | 0.69 (0.41–1.14) |

| Enhanced SOC + alarm vs enhanced SOC | 1 | 1.27 (0.73–2.23) | 1.26 (1.00–1.58) |

| Enhanced SOC + calendar vs enhanced SOC | 1 | 1.08 (0.52–2.25) | 1.25 (0.67–2.57) |

| Enhanced SOC + weekly SMS vs enhanced SOC | 1 | 1.24 (0.68–2.26) | 1.42 (0.86–2.35) |

| Enhanced SOC + treatment supporter vs enhanced SOC | 5 | 1.13 (0.88–1.46) | 1.26 (1.00–1.58) |

| Enhanced SOC + alarm vs alarm | 1 | 1.55 (0.89–2.72) | 1.56 (0.89–2.74) |

| Enhanced SOC + treatment supporter vs enhanced SOC + calendar |

1 | 1.21 (0.33–4.38) | 1.01 (0.48–1.93) |

| Weekly SMS vs daily SMS | 1 | 1.59 (1.00–2.53) | 1.56 (1.01–2.40) |

Appendix 6.

Direct vs indirect evidence for viral suppression

| Indirect comparisons | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct comparisons | SOC | 1.45 (0.37, 7.43) |

0.99 (0.12, 7.26) |

1.55 (0.21, 12.18) |

1.54 (0.45, 6.10) |

0.61 (0.33, 1.11) |

| 2.62 (0.91, 3.67) |

eSOC | 1.07 (0.28, 3.81) |

||||

|

0.99 (0.51, 1.64) |

Alarm | |||||

| 1.55 (1.00, 1.98) |

Weekly SMS | |||||

| 1.37 (1.01, 1.67) |

1.31 (0.52, 2.23) |

eSOC + treatment supporter |

||||

|

0.61 (0.34, 1.21) |

SOC + supporter |

|||||

Note: Each cell represents the comparison (odds ratio and 95% CrI) of the row treatment versus the column treatment below the diagonal and of the column treatment versus the row treatment above the diagonal.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Edward Mills has participated in the development of the PRISMA extension for network meta-analysis.

Ethics: An ethics statement was not required for this work.

Author Contributions: EJM, RL, KT, ML, KM, SK, SL, RG, YC, KRA, HT, CP, RHR, LM, LT, MHC, IBW, AL, OAU, JS, DB, SY, TB, MJS, NF and JBN conceived and designed the study; EJM, RL, ML, KM, SK and JBN acquired the data; KT, ML and SK conducted the statistical analyses; EJM, ML, KM and SK drafted the manuscript; EJM, RL, KT, ML, KM, SK, SL, RG, YC, KRA, HT, CP, RHR, LM, LT, MHC, IBW, AL, OAU, JS, DB, SY, TB, MJS, NF and JBN conceived and designed the study; EJM, RL, ML, KM, SK and JBN provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills EJ, Lester R, Ford N. Promoting long term adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Bmj. 2012;344:e4173. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, et al. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC medicine. 2014;12:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0142-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauci AS, Marston HD. Achieving an AIDS-free world: science and implementation. Lancet. 2013;382:1461–1462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:817–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. W-284, W-5, W-6, W-7, W-8, W-9, W-90, W-91, W-92, W-93, W-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, et al. Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:942–951. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiser SD, Palar K, Frongillo EA, et al. Longitudinal assessment of associations between food insecurity, antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes in rural Uganda. Aids. 2014;28:115–120. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000433238.93986.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaiyachati KH, Ogbuoji O, Price M, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a rapid systematic review. Aids. 2014;28(Suppl 2):S187–S204. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, et al. Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2011;11:942–951. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: part 1. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2011;14:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Statistics in medicine. 2004;23:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills EJ, Ioannidis JP, Thorlund K, et al. How to use an article reporting a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:1246–1253. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, et al. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Statistical methods in medical research. 2008;17:279–301. doi: 10.1177/0962280207080643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Statistics in medicine. 2004;23:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP. Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. Bmj. 2013;346:f2914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ, et al. Evidence synthesis for decision making 3: heterogeneity--subgroups, meta-regression, bias, and bias-adjustment. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2013;33:618–640. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13485157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, et al. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idoko JA, Agbaji O, Fau - Agaba P, Agaba P, Fau - Akolo C, et al. Direct observation therapy-highly active antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting: the use of community treatment support can be effective. doi: 10.1258/095646207782212252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabore I, Bloem J, Fau - Etheredge G, Etheredge G, Fau - Obiero W, et al. The effect of community-based support services on clinical efficacy and health-related quality of life in HIV/AIDS patients in resource-limited settings in sub-Saharan Africa. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherr KH, Micek Ma, Fau - Gimbel SO, Gimbel So, Fau - Gloyd SS, et al. Quality of HIV care provided by non-physician clinicians and physicians in Mozambique: a retrospective cohort study. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000366083.75945.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stubbs BA, Micek MA, Pfeiffer JT, et al. Treatment partners and adherence to HAART in Central Mozambique. AIDS care. 2009;21:1412–1419. doi: 10.1080/09540120902814395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pienaar D, Myer L, Cleary S, et al. Models of Care for Antiretroviral Service Delivery. Cape Town: University of Capetown; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thurman TR, Haas Lj, Fau - Dushimimana A, Dushimimana A, Fau - Lavin B, et al. Evaluation of a case management program for HIV clients in Rwanda. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torpey KE, Kabaso Me, Fau - Mutale LN, Mutale Ln, Fau - Kamanga MK, et al. Adherence support workers: a way to address human resource constraints in antiretroviral treatment programs in the public health setting in Zambia. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux S. Diary cards: preliminary evaluation of an intervention tool for improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy and TB preventative therapy in people living with HIV/AIDS. University of the Western Cape; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirkle CM, Boileau C, Fau - Nguyen VK, Nguyen Vk, Fau - Machouf N, et al. Impact of a modified directly administered antiretroviral treatment intervention on virological outcome in HIV-infected patients treated in Burkina Faso and Mali. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byron E, Gillespie S, Fau - Nangami M, Nangami M. Integrating nutrition security with treatment of people living with HIV: lessons from Kenya. doi: 10.1177/156482650802900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igumbor JO, Scheepers E, Fau - Ebrahim R, Ebrahim R, Fau - Jason A, et al. An evaluation of the impact of a community-based adherence support programme on ART outcomes in selected government HIV treatment sites in South Africa. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rich ML, Miller Ac, Fau - Niyigena P, Niyigena P, Fau - Franke MF, et al. Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824476c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cantrell RA, Sinkala M, Fau - Megazinni K, Megazinni K, Fau - Lawson-Marriott S, et al. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansoor LE, Dowse R. Medicines information and adherence in HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2006;31:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holstad MM, Essien JE, Ekong E, et al. Motivational groups support adherence to antiretroviral therapy and use of risk reduction behaviors in HIV positive Nigerian women: a pilot study. African journal of reproductive health. 2012;16:14–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiweewa FM, Wabwire D, Nakibuuka J, et al. Noninferiority of a task-shifting HIV care and treatment model using peer counselors and nurses among Ugandan women initiated on ART: evidence from a randomized trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013;63:e125–e132. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182987ce6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Loggerenberg F, Grant A, Naidoo K, et al. Group counseling achieves high adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Results of the CAPRISA 058 randomized controlled trial comparing group versus individualized adherence counseling strategies in Durban, South Africa. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2010;9(4):260. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffar S, Amuron B, Fau - Foster S, Foster S, Fau - Birungi J, et al. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wamalwa DC, Farquhar C, Fau - Obimbo EM, Obimbo Em, Fau - Selig S, et al. Medication diaries do not improve outcomes with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Kenyan children: a randomized clinical trial. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munyao P, Luchters S, Chersich MF, et al. Implementation of clinic-based modified-directly observed therapy (m-DOT) for ART; experiences in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS care. 2010;22:187–194. doi: 10.1080/09540120903111452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang LW, Kagaayi J, Nakigozi G, et al. Effect of peer health workers on AIDS care in Rakai, Uganda: a cluster-randomized trial. PloS one. 2010;5:e10923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic outcomes. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunutsor S, Walley J, Katabira E, et al. Improving clinic attendance and adherence to antiretroviral therapy through a treatment supporter intervention in Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS and behavior. 2011;15:1795–1802. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1838–1845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maduka O, Tobin-West CI. Adherence counseling and reminder text messages improve uptake of antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2013;16:302–308. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.113451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Ongolo-Zogo P, et al. The Cameroon Mobile Phone SMS (CAMPS) trial: a randomized trial of text messaging versus usual care for adherence to antiretroviral therapy. PloS one. 2012;7:e46909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mugusi F, Mugusi S, Bakari M, et al. Enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy at the HIV clinic in resource constrained countries; the Tanzanian experience. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2009;14:1226–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nachega JB, Chaisson RE, Goliath R, et al. Randomized controlled trial of trained patient-nominated treatment supporters providing partial directly observed antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2010;24:1273–1280. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339e20e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearson CR, Micek MA, Simoni JM, et al. Randomized control trial of peer-delivered, modified directly observed therapy for HAART in Mozambique. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2007;46:238–244. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318153f7ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. Aids. 2011;25:825–834. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834380c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarna A, Luchters S, Geibel S, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy of modified directly observed antiretroviral treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: a randomized trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2008;48:611–619. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181806bf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taiwo BO, Idoko JA, Welty LJ, et al. Assessing the viorologic and adherence benefits of patient-selected HIV treatment partners in a resource-limited setting. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2010;54:85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000371678.25873.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peltzer K, Ramlagan S, Jones D, et al. Efficacy of a lay health worker led group antiretroviral medication adherence training among non-adherent HIV-positive patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: results from a randomized trial. SAHARA J : journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance / SAHARA, Human Sciences Research Council. 2012;9:218–226. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2012.745640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gross R, Zheng L, La Rosa A, et al. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Boston, MA: International Antiviral Society - USA; 2014. Partner-based intervention for adherence to second-line ART: A multinational trial (ACTG A5234) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ford N, Nachega JB, Engel ME, et al. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2009;374:2064–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic outcomes. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lester R, Karanja S. Mobile phones: exceptional tools for HIV/AIDS, health, and crisis management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:738–739. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thirumurthy H, Lester RT. M-health for health behaviour change in resource-limited settings: applications to HIV care and beyond. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:390–392. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hart JE, Jeon CY, Ivers LC, et al. Effect of directly observed therapy for highly active antiretroviral therapy on virologic, immunologic, and adherence outcomes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2010;54:167–179. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d9a330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Higgins JP, Whitehead A. Borrowing strength from external trials in a meta-analysis. Statistics in medicine. 1996;15:2733–2749. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19961230)15:24<2733::AID-SIM562>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duwell MM, Knowlton AR, Nachega JB, et al. Patient-nominated, community-based HIV treatment supporters: patient perspectives, feasibility, challenges, and factors for success in HIV-infected South African adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:96–102. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nachega JB, Knowlton AR, Deluca A, et al. Treatment supporter to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected South African adults. A qualitative study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S127–S133. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248349.25630.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thirumurthy H, Siripong N, Vreeman RC, et al. Differences between self-reported and electronically monitored adherence among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. Aids. 2012;26:2399–2403. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359aa68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bangsberg DR, Mills EJ. Long-term adherence to antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: a bitter pill to swallow. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:25–28. doi: 10.3851/IMP2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR, Shen JM, et al. Heterogeneity Among Studies in Rates of Decline of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Over Time: Results From the Multisite Adherence Collaboration on HIV 14 Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:448–454. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thorlund K, Mills EJ. Sample size and power considerations in network meta-analysis. Systematic reviews. 2012;1:41. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, et al. Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9:e99682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]