Abstract

Introduction

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) in pregnancy is rare and is most commonly caused by adhesions from previous abdominal surgery. Previous literature reviews have emphasised the need for prompt laparotomy in all cases of SBO because of the significant risks of fetal loss and maternal mortality. We undertook a review of the contemporary literature to determine the optimum management strategy for SBO in pregnancy.

Methods

The MEDLINE® and PubMed databases were searched for cases of SBO in pregnancy between 1992 and 2014. Two cases from our own institution were also reviewed.

Results

Forty-six cases of SBO in pregnancy were identified, with adhesions being the most common aetiology (50%). The overall risk of fetal loss was 17% and the maternal mortality rate was 2%. In cases of adhesional SBO, 91% of cases were managed surgically, with 14% fetal loss. Two cases (9%) were managed conservatively with no complications. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used to diagnose SBO in 11% of cases.

Conclusions

Based on our experience and the contemporary literature, we recommend that urgent MRI of the abdomen should be undertaken to diagnose the aetiology of SBO in pregnancy. In cases of adhesional SBO, conservative treatment may be safely commenced, with a low threshold for laparotomy. In other causes, such as volvulus or internal hernia, laparotomy remains the treatment of choice.

Keywords: Small bowel obstruction, Pregnancy

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is most commonly caused by adhesions from previous abdominal surgery and, more rarely, by hernias, malignancy, volvulus or intussusception. The preferred initial treatment of adhesional SBO is non-operative whereas other causes of SBO usually require expeditious surgery. SBO during pregnancy is an extremely rare clinical event with an incidence of 0.001–0.003% and it is secondary to adhesions in around 70% of cases.1 Traditional teaching would dictate that the safest way to protect the fetus is to treat the mother in the same way as a non-pregnant woman (ie conservatively) while avoiding ionising radiation and harmful drugs.2 However, the historical literature suggests a more aggressive surgical approach may be necessary.3,4

The literature on this topic was last reviewed over 20 years ago.4 Since this time, major surgery for obesity and restorative proctocolectomy for inflammatory bowel disease or familial cancer syndromes has become increasingly common in young women of childbearing age. As a result, the average practising general surgeon is now more likely to come across a case of SBO in pregnancy than in the past. We set out to review the literature on SBO in pregnancy from 1992 to 2014 systematically to determine an optimal management strategy for the contemporary surgeon when this rare condition is encountered. In this report, we also include two cases managed in our own institution.

Our single centre experience

Our own institutional experience includes three cases, of which one has already been reported.5 The remaining two cases are presented below.

Case 1: A 30-year-old woman presented to the obstetrics team in her 39th week of pregnancy with a 1-day history of sudden onset colicky abdominal pain, bilious vomiting and obstipation. Past surgical history included a laparotomy and untwisting of a small bowel volvulus, and a subsequent laparoscopic adhesiolysis for adhesional small bowel obstruction one year later. On initial examination, the patient had normal observations. Her abdomen was distended but soft. Routine blood tests were unremarkable. A provisional diagnosis of possible SBO was made and a nasogastric tube was inserted, returning minimal aspirate. The patient was treated conservatively but several hours later started with contractions and fetal bradycardia was noted.

Ultrasonography prior to the start of an emergency Caesarean section demonstrated no fetal heart rate. Delivery of a dead infant occurred and subsequent computed tomography (CT) confirmed high grade SBO 10–15cm from the ileocaecal valve with a possible recurrence of the small bowel volvulus. At laparotomy, there were several small bowel loops adherent to one another volved around a long thin small bowel mesentery. The volvulus was untwisted and adhesiolysis was performed. The patient made an uneventful recovery.

Case 2: A 33-year-old woman presented to the obstetric team in her 27th week of pregnancy with sudden onset abdominal pain and bilious vomiting. She was pregnant with twins following her eighth cycle of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). She had an extensive past surgical history including two laparoscopic ovarian cystectomies, of which one was complicated by an iatrogenic enterotomy requiring emergency laparotomy. She had also had two ectopic pregnancies resulting in bilateral salpingectomies.

The patient had abdominal ultrasonography, which revealed dilated, fluid filled loops of small bowel. She went on to have magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the same day, which confirmed adhesional SBO. She was treated conservatively for 6 days with nasogastric tube decompression and intravenous fluids until she reached her 28th week of gestation. At this gestational age, it was felt that if a laparotomy triggered labour, the chances of fetal survival would be greatly improved. Repeat MRI at 28 gestational weeks showed non-resolving SBO. The patient underwent a laparotomy and adhesiolysis. Postoperatively, she made a slow but steady recovery before being discharged on her tenth postoperative day. She subsequently underwent an emergency Caesarean section at 30 weeks, having developed HELLP (Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelet) syndrome, giving birth to two healthy twins.

Methods

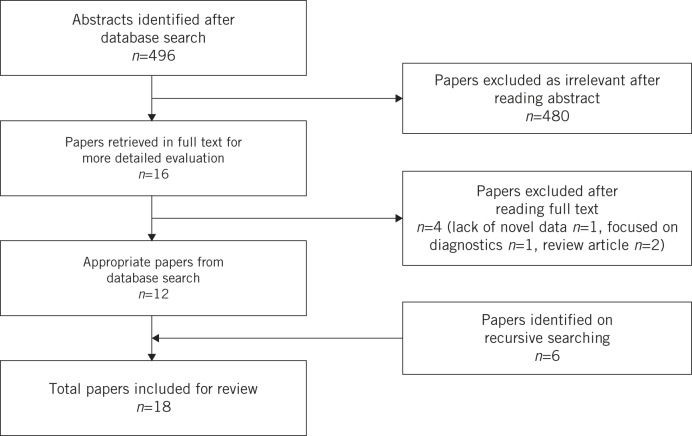

The MEDLINE® and PubMed databases (1992–2014) were searched using the Boolean operators [small bowel obstruction] AND [preg* OR foet*]. Inclusion criteria included any paper type dealing with small bowel obstruction in pregnancy. Initially retrieved articles were screened for relevance based on title, keywords and abstract review. Selected articles were then obtained in full text and reviewed by three independent reviewers (PW, MB, JW). Reference lists of included articles were searched recursively for further relevant papers and the contents of pertinent journals were hand searched. Google Scholar® was also interrogated for any additional papers. A full diagram of the search strategy is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search strategy

Results

The search strategy returned 496 citations. Of these, 480 were excluded on the initial screen as irrelevant, leaving 16 for full text review. Six further articles were identified from recursive searching, Google Scholar® and hand searching of journals. Four papers were excluded as they did not include any novel data (n=1), were focused on diagnostics (n=1) or were review articles (n=2). As a result, 18 papers were included in the systematic review.

The literature on SBO in pregnancy has been summarised twice: 150 cases in 19663 and the subsequent 66 cases in 1992.4 In the contemporary literature (1992–2014), we identified 12 published clinical case reports of SBO in pregnancy5–16 and 6 small case series.17–22

Case reports

The 12 case reports since 1992 are summarised in Table 1 and include three cases of volvulus in pregnancy causing SBO (25%), one case of an internal hernia (8%), one case of ileal pouch compression (8%), one case of a mesenteric band (8%) and six cases of adhesional SBO (50%). One case of SBO occurred in the first trimester, five cases in the second trimester and six cases in the third trimester. Various imaging studies were performed to diagnose SBO. Four patients (33%) had an abdominal x-ray, ten (83%) had ultrasonography of the abdomen, four (33%) had MRI of the abdomen and three (25%) had CT of the abdomen/pelvis.

Table 1.

Summary of case reports (1992–2014)

| Study | Aetiology of SBO | Gestation | Imaging | Management | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBO = small bowel obstruction; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography; IV = intravenous | |||||

| *following a period of failed conservative management | |||||

| Wax, 19936 | Volvulus | 24 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, IV pyelography, abdominal x-ray | Surgery | Fetal mortality |

| Walker, 19977 | Ileal pouch compression | 36 wks | Abdominal x-ray | Conservative | Nil |

| Watanabe, 20008 | Adhesions | 13 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, MRI | Surgery | Nil |

| Phillips, 20049 | Adhesions | 26 wks | Abdominal x-ray | Conservative | Nil |

| Biswas, 200610 | Volvulus | 31 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, CT | Surgery | Nil |

| Bellanger, 200611 | Internal hernia | 33 wks | IV pyelography, ultrasonography abdomen, CT | Surgery | Nil |

| Redlich, 200712 | Adhesions | 29 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen | Surgery | Nil |

| Witherspoon, 20105 | Adhesions | 26 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, MRI | Surgery* | Nil |

| Vassiliou, 201213 | Volvulus | 21 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, MRI | Surgery* | Nil |

| Lazaridis, 201314 | Adhesions (secondary to ovarian torsion) | 12 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, MRI | Surgery* | Nil |

| Rauff, 201315 | Mesenteric band | 32 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, CT | Surgery* | Nil |

| Zachariah, 201416 | Adhesions | 29 wks | Ultrasonography abdomen, abdominal x-ray | Surgery* | Nil |

There was one fetal death following surgery for a small bowel volvulus in the second trimester.6 In the six cases of adhesional SBO, five patients (83%) were treated surgically, including three cases of failed conservative treatment. One patient in the second trimester was treated successfully with conservative measures and had an elective Caesarean section at 38 weeks.9

Case series

The six case series are summarised in Table 2 along with our case series and the two previous literature reviews. Of the 34 cases, there were 17 cases of adhesional SBO (50%), four cases of intussusception (12%), five cases of internal hernia (15%), three cases of volvulus (9%) and five cases where the aetiology was not documented.19 In cases where the gestational age was disclosed (n=29), 2 cases of SBO occurred in the first trimester, 13 in the second trimester and 14 in the third trimester. There were seven fetal deaths in total, three of which were in cases of adhesional SBO, and one maternal death in a case of volvulus causing SBO.

Table 2.

Summary of case series (1992–2014) and previous literature reviews

| Study | Location | Years | Cases | Conservative | Surgery | Maternal mortality | Fetal loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 patient had an elective abortion; | |||||||

| bincludes Witherspoon et al (2010)5 from Table 1 | |||||||

| Meyerson, 199517 | Detroit, US | 1972–1992 | 8 | 13% | 87% | 0% | 43%a |

| Chiedozi, 199918 | Benin City, Nigeria | 1984–1999 | 10 | 0% | 100% | 10% | 20% |

| Jones, 200219 | Brisbane, Australia | 1990–2000 | 6 | 33% | 66% | 0% | 17% |

| Chang, 200620 | Kohsiung, Taiwan | 1984–2002 | 4 | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0%a |

| Torres-Villalobos, 200821 | Minneapolis, US | 2008 | 2 | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Tuyeras, 201322 | Paris, France | 2013 | 2 | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Present study | Leeds, UK | 2009–2012 | 3b | 0% | 100% | 0% | 33% |

| Previous literature reviews | |||||||

| Goldthorp, 19663 | Review | 1945–1965 | 150 | 0.7% (n=1) | 99.3% | 12% | 20% |

| Perdue, 19924 | Review | 1966–1992 | 66 | 0% | 100% | 6% | 26% |

In adhesional SBO (17 cases), 16 cases (94%) were treated surgically, including 13 (81%) where conservative treatment failed. One patient in the third trimester was successfully managed conservatively to term. There were no fetal deaths in the first trimester, two fetal deaths in the second trimester (22%) and one fetal death in the third trimester (17%).

Discussion

SBO is a common clinical entity that very occasionally occurs during pregnancy. It is so rare that an individual general surgeon is likely to observe only 1–2 cases of SBO in pregnancy during his or her career. As a randomised clinical trial would not be acceptable ethically, we must rely on single centre experiences and case reports to make suggestions for optimal management.

When SBO occurs in pregnancy, it carries a significant risk to mother and fetus (Table 3). In this review, the overall rate of fetal loss was 17% (n=8) and the maternal mortality rate was 2% (n=1). These figures have improved since the last review in 1992, where fetal loss occurred in 26% of cases and maternal mortality was 6%.4 As with previous reviews, adhesions were the most common cause of SBO (n=23, 50%). Twenty-one patients (91%) with adhesional SBO were managed surgically, including sixteen (76%) who failed conservative treatment (Table 4).

Table 3.

All causes of small bowel obstruction: combined case reports and series by trimester (1992–2014)

| Trimester | Cases | Conservative | Conservative mortality | Surgery | Surgery mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | Fetal | Maternal | Fetal | ||||

| aincludes 2 patients who failed conservative treatment; | |||||||

| bincludes 9 patients who failed conservative treatment; | |||||||

| cincludes 11 patients who failed conservative treatment; insufficient details to include 5 cases from Jones and Hillen (2002)19 | |||||||

| 1 (1–12 wks) | 3 | 0% | – | – | 100% (n=3)a | 0% | 33% (n=1) |

| 2 (13–28 wks) | 18 | 6% (n=1) | 0% | 0% | 94% (n=17)b | 6% (n=1) | 29% (n=5) |

| 3 (29–40 wks) | 20 | 10% (n=2) | 0% | 0% | 90% (n=18)c | 0% | 11% (n=2) |

Table 4.

Adhesional small bowel obstruction: combined case reports and case series by trimester (1992–2014)

| Trimester | Cases | Conservative | Conservative mortality | Surgery | Surgery mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | Fetal | Maternal | Fetal | ||||

| aincludes 1 patient who failed conservative treatment; | |||||||

| bincludes 8 patients who failed conservative treatment; | |||||||

| cincludes 7 patients who failed conservative treatment; | |||||||

| d1 elective abortion postoperatively | |||||||

| 1 (1–12 wks) | 2 | 0% | – | – | 100%a | 0% | 0%d |

| 2 (13–28 wks) | 12 | 8% (n=1) | 0% | 0% | 92% (n=11)b | 0% | 18% (n=2) |

| 3 (29–40 wks) | 9 | 11% (n=1) | 0% | 0% | 89% (n=8)c | 0% | 13% (n=1) |

Three of the fetal deaths occurred in patients with adhesional SBO. There were no fetal deaths in the first trimester, two in the second trimester and one in the third trimester. All three cases of fetal loss were from the same case series17 and in all three cases, the patients were managed surgically. Two of the patients were operated on 13 days after the onset of symptoms and the other patient after 6 days.

Two patients with adhesional SBO were managed conservatively.9,17 Meyerson et al managed a patient with adhesional SBO conservatively from 31 weeks’ gestation up until delivery at 36 weeks.17 Phillips et al managed a patient with SBO conservatively at 26 weeks’ gestation, resolving the acute episode.9 The patient continued to have episodes of incomplete obstruction throughout pregnancy and was managed with instigation of an elemental diet until she delivered at 38 weeks. In both cases, there was no fetal loss or maternal mortality.

Diagnosis of SBO can be difficult to make as symptoms are often attributed mistakenly to the pregnancy and there can be a reluctance to request plain films owing to the risks of ionising radiation. Both of these factors can lead to a delay in diagnosis and initiating treatment. Previous literature reviews have placed great importance on aggressive management with prompt laparotomy once a diagnosis of SBO has been made, with no role for conservative treatment,3,4 part of this argument being that the aetiology of the SBO cannot be determined until a laparotomy has been performed.

Since the last literature review in 1992,4 CT and MRI have become more readily available and have been employed in the acute setting to diagnose SBO in pregnancy. In the current review, six patients (13%) had urgent CT and five separate patients (11%) had urgent MRI. MRI is capable of multiplanar imaging, excellent soft tissue contrast and avoids the risks of ionising radiation. This makes it a useful tool for imaging the small bowel and diagnosing SBO in pregnancy.23

In 2013 the American College of Radiology concluded that present data have not documented conclusively any deleterious effects of MRI exposure on the developing fetus, with no special considerations being recommended for any trimester of pregnancy.24 In case 2 from our institution presented above, MRI diagnosed adhesional SBO in a twin IVF pregnancy at 27 weeks’ gestation. This allowed a trial of conservative treatment until the 28th week of gestation where if a laparotomy had triggered labour, the chances of fetal survival would have been greatly improved. The overall risks of laparotomy triggering premature labour are significant. In the contemporary literature, it occurred in three cases (7%), with a 100% fetal mortality rate.6,18,19

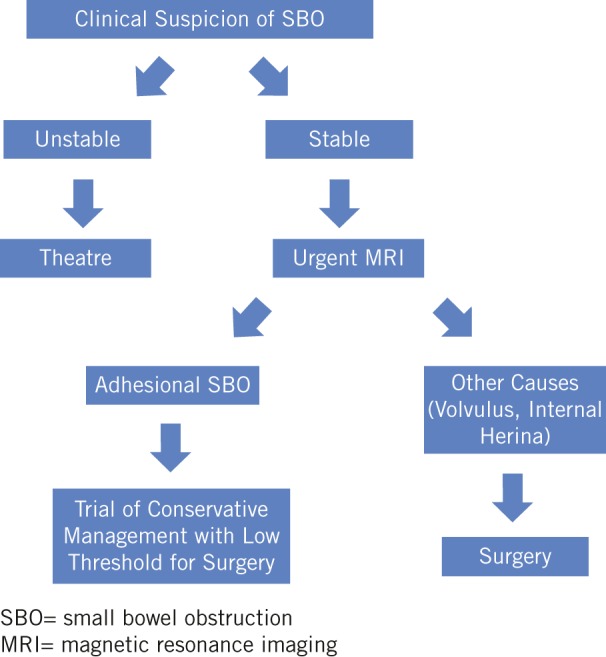

There is no agreed treatment strategy for patients presenting with SBO in pregnancy. Optimal management depends on a number of factors including aetiology of the obstruction and gestational age of the fetus. As with the non-pregnant patient, if the aetiology is a volvulus or internal hernia, then the treatment of choice is surgery. However, with adhesional SBO, the management is less clear cut. Based on the contemporary literature and our own personal experience, we recommend the strategy in Figure 2. While in agreement with previous literature reviews regarding the need for prompt laparotomy in most cases of SBO, the contemporary literature and our own experience suggest that patients with confirmed adhesional obstruction may be managed conservatively in the first instance but with a low threshold for progressing to laparotomy.

Figure 2.

Proposed algorithm for the management of SBO in pregnancy

Conclusions

SBO in pregnancy is most commonly due to adhesions from previous abdominal surgery, and carries significant risks to both mother and fetus. Cases should be managed on an individual basis with a multidisciplinary team approach. We recommend that all patients with clinical suspicion of SBO in pregnancy should have urgent MRI to diagnose and determine the aetiology of the SBO. In cases of adhesional obstruction, patients may be managed conservatively initially, with a low threshold for laparotomy. In other cases, such as small bowel volvulus or internal hernia, there is no role for conservative treatment and prompt laparotomy following resuscitation is recommended.

References

- 1.Sivanesaratnam V. The acute abdomen and the obstetrician. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2000; : 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parangi S, Levine D, Henry A et al. Surgical gastrointestinal disorders during pregnancy. Am J Surg 2007; : 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldthorp WO. Intestinal obstruction during pregnancy and the puerperium. Br J Clin Pract 1966; : 367–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perdue PW, Johnson HW, Stafford PW. Intestinal obstruction complicating pregnancy. Am J Surg 1992; : 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witherspoon P, Chalmers AG, Sagar PM. Successful pregnancy after laparoscopic ileal pouch-anal anastomosis complicated by small bowel obstruction secondary to a single band adhesion. Colorectal Dis 2010; : 490–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wax JR, Christie TL. Complete small-bowel volvulus complicating the second trimester. Obstet Gynecol 1993; (4 Pt 2 Suppl): 689–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker M, Sylvain J, Stern H. Bowel obstruction in a pregnant patient with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Can J Surg 1997; : 471–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe S, Otsubo Y, Shinagawa T, Araki T. Small bowel obstruction in early pregnancy treated by jejunotomy and total parenteral nutrition. Obstet Gynecol 2000; : 812–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips M, Curtis P, Karanjia N. An elemental diet for bowel obstruction in pregnancy: a case study. J Hum Nutr Diet 2004; : 543–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswas S, Gray KD, Cotton BA. Intestinal obstruction in pregnancy: a case of small bowel volvulus and review of the literature. Am Surg 2006; : 1,218–1,221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellanger DE, Ruiz JF, Solar K. Small bowel obstruction complicating pregnancy after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006; : 490–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redlich A, Rickes S, Costa SD, Wolff S. Small bowel obstruction in pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007; : 381–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vassiliou I, Tympa A, Derpapas M et al. Small bowel ischemia due to jejunum volvulus in pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2012; 485863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Lazaridis A, Maclaran K, Behar N, Narayanan P. A rare case of small bowel obstruction secondary to ovarian torsion in an IVF pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep 2013; bcr2013008551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rauff S, Chang SK, Tan EK. Intestinal obstruction in pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2013; 564838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Zachariah SK, Fenn MG. Acute intestinal obstruction complicating pregnancy: diagnosis and surgical management. BMJ Case Rep 2014; bcr2013203235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Meyerson S, Holtz T, Ehrinpreis M, Dhar R. Small bowel obstruction in pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; : 299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiedozi LC, Ajabor LN, Iweze FI. Small intestinal obstruction in pregnancy and puerperium. Saudi J Gastroenterol 1999; : 134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones I, Hillen J. Small bowel obstruction during pregnancy: a case report. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2002; : 311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang YT, Huang YS, Chan HM et al. Intestinal obstruction during pregnancy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2006; : 20–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres-Villalobos GM, Kellogg TA, Leslie DB et al. Small bowel obstruction and internal hernias during pregnancy after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg 2009; : 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuyeras G, Pappalardo E, Msika S. Acute small bowel obstruction following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass during pregnancy: two different presentations. J Surg Case Rep 2012; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.McKenna DA, Meehan CP, Alhajeri AN et al. The use of MRI to demonstrate small bowel obstruction during pregnancy. Br J Radiol 2007; : e11–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; : 501–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]