Abstract

Background

Identify the proximity of anatomic structures during the modified Henry approach (MHA).

Methods

Distances between median nerve (MN), palmar cutaneous branch (PCB), radial artery (RA) and the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) were measured at the wrist crease (WC), 5 and 10 cm proximal in 16 fresh frozen cadavers. The FPL origin and innervation was measured.

Results

Most at risk was the MN proximally and the PCB distally while the RA was safe. Innervation occurred at the proximal third of the FPL's origin along the ulnar aspect.

Conclusion

The MHA is safe when understanding the proximity of structures.

Keywords: Modified Henry approach, Distal radius, Fracture, Exposure

1. Introduction

Distal radius fractures are among the most common fractures seen in adults.1, 2 Operative treatment of distal radius fractures has increased dramatically over recent years secondary to the introduction of volar locking plates.3 Koval et al. noted that operative treatment of distal radius fractures increased from 42 to 81% in 8 years.4 The most common surgical approach for the application of volar plates is through the modified Henry approach. Complications from volar plating of distal radius fractures vary from 3 to 27% which includes neurovascular injury.5, 6, 7, 8 Accurate understanding of the neurovascular anatomy of the volar aspect of the distal radius is therefore fundamental in avoiding iatrogenic injury during the surgical approach.9

The two most common approaches to the distal radius are the classic Henry approach between the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon and the radial artery, and the modified Henry approach through the sheath of the FCR tendon. Both approaches use an 8–10 cm skin incision directly over the FCR tendon differing only in the superficial interval utilized to expose the deep volar compartment.10 The classic Henry approach requires identification and protection of the radial artery, while the FCR tendon sheath and the palmar cutaneous branch (PCB) of the median nerve are preserved. The modified Henry approach requires incision of the FCR tendon sheath to allow ulnarward retraction of the FCR tendon. Incising the floor of the FCR compartment allows access to the deep volar compartment. The advantage of this approach is avoiding dissection and potentially injury to the radial artery; however, the PCB of the median nerve does run within the sheath of the FCR tendon, thus subjecting it to potential injury during surgery.

Upon entering the deep compartment of the forearm, the modified Henry approach often requires elevation of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) off the distal radius to improve visualization of the fracture. In the immediate postoperative period, FPL weakness has been reported.11 It is unknown how much of the FPL origin can be elevated safely prior to weakening the muscle or possibly causing denervation of the FPL.

In addition to de-innervation of the FPL, other nerves are at risk of injury during the Henry approach. The median nerve and its PCB are located on the ulnar aspect of the FCR. Several studies have looked at the anatomic relationship of these structures at the level of the wrist, but the relationship of these structures are not static and have not been described through out the whole modified Henry incision.

The aim of this study was to examine the modified Henry approach to the distal radius for a distance of 10 cm from the volar wrist crease, documenting the proximity of key neurovascular structures including the median nerve, the PCB of the median nerve and the radial artery to the FCR tendon. We additionally were interested in the location, length and innervation pattern of the FPL muscle origin. We hypothesized that incision through the FCR tendon sheath would not place any of the vital neurovascular structures at direct risk of injury and distal elevation of the FPL origin may weaken but would not deinnervate the muscle; however a more detailed understanding of the regional anatomy may decrease neurovascular complications reported in the literature

2. Methods

Sixteen fresh frozen upper extremity cadavers were amputated above the elbow. All limbs were matched for size. No limbs had evidence of previous wrist or forearm surgery. Demographic data for the cadavers is not available in our programs cadaveric donor program.

Full thickness flaps were raised along the line defined by the course of the FCR tendon along the length of the forearm. Care was taken not to disturb the anatomic position of neurovascular structures. A standard ruler was used to make measurements. The width of the FCR tendon was measured at the level of the wrist crease in eight of the cadavers. All measurements were made with reference to the most distinctive wrist crease. The distance from the radial aspect of the FCR tendon to the ulnar edge of the radial artery was measured at the wrist crease and at 5 and 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease.

The distance between the radial edge of the median nerve and the ulnar border of the FCR tendon were measured at the same three reference points. After obtaining measurements for the radial artery and median nerve, the interval between the FCR and median nerve was dissected to identify the PCB of the median nerve. The distance between the origin of the PCB and wrist crease was measured. In eight of the cadavers, the sheath of the FCR tendon was then opened and the relationship between the PCB and the FCR tendon was examined at the level of the wrist crease.

Finally the FPL was then dissected; the distal end of the bony muscular origin was identified and measured from the wrist crease. The beginning of the bony muscular origin was identified and measured from the wrist crease. Lastly, the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) nerve was then identified proximally, followed distally until all branches of AIN that were identified and measured. The muscle was divided into thirds in which third of the muscle the branches innervated the muscle.

3. Results:

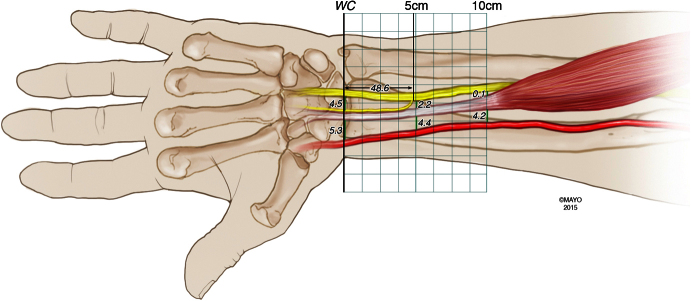

The FCR tendon was an average of 5.6 mm (std dev: 0.99) wide at the level of the wrist crease (Table 1). The distance between the radial aspect of the FCR tendon and the ulnar aspect of the radial artery was wider proximally than distally. At 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease, the average distance was 4.2 mm (std dev: 1.8), 4.4 mm (std dev: 1.5) at 5 cm and 5.3 mm (std dev: 2.7) at the level of the wrist crease.

Table 1.

Averages and standard deviation of measurements in centimeters of all 16 cadavers.

| Anatomic landmarks measured | Average distance (mm) | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Distance between radial aspect of FCR and ulnar aspect of radial artery at wrist crease (mm) | 5.3 | 2.7 |

| Distance between radial aspect of FCR and ulnar aspect of radial artery 5 cm proximal to wrist crease (mm) | 4.4 | 1.5 |

| Distance between radial aspect of FCR and ulnar aspect of radial artery 10 cm proximal to wrist crease (mm) | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| Distance between ulnar aspect of FCR and radial aspect of median nerve at wrist crease (mm) | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| Distance between ulnar aspect of FCR and radial aspect of median nerve 5 cm proximal to wrist crease (mm) | 2.2 | 1.3 |

| Distance between ulnar aspect of FCR and radial aspect of median nerve 10 cm proximal to wrist crease (mm) | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Distance between ulnar aspect of FCR and radial aspect of PCB at wrist crease (mm) | 0 | 0 |

| Bifurcation of PCB from median nerve distance from wrist crease | 48.6 | 18 |

| PCB ever cross FCR? | No | |

| Width of FCR tendon at wrist crease (mm) | 5.625 | 0.99 |

| Proximal aspect of FPL origin to WC | 199 | 23 |

| Distal aspect of FPL origin to WC | 81.5 | 13.5 |

| Length of origin footprint of FPL | 117.5 | 11.2 |

| Innervation of FPL by AIN | Proximal 1/3 | |

| Innervation of FPL by AIN | Ulnar aspect |

FCR, flexor carpi radialis; PCB, palmar cutaneous branch; FPL, flexor pollicis longus; WC, wrist crease; AIN, anterior interosseous nerve.

While the median nerve lies separate from the FCR tendon at the wrist, the two structures were closely related proximally in the forearm. The radial aspect of the median nerve was 0.1 mm (std dev: .3) away from the ulnar aspect of the FCR at 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease and continued to diverge going distally. At 5 cm proximal to the wrist crease, the two anatomic structures are 2.2 mm apart (std dev: 1.3) and by the wrist crease the two structures were 4.5 mm (std dev: 2.2) apart.

The PCB of the median nerve branched off from the radial aspect of the median nerve at an average of 48.6 mm (std dev. 18) proximal to the wrist crease and tracked radially toward the FCR (Fig. 1). The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve ran within the ulnar edge of the sheath of the FCR tendon but never crossed the tendon. A schematic of the distances are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

All cadavers were dissected and the PCB (*), FCR (FCR) and median nerve (M) were isolated. The proximity of the median nerve to the ulnar aspect of the FCR tendon at the level of the wrist crease, 5 cm proximal to the wrist crease, and 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease were obtained. In addition, the PCB's path was dissected out and measured in relation to the ulnar aspect of the FCR. Ulnar aspect of the wrist is denoted with a U and the radial aspect is denoted with a R.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the proximity of the median nerve and radial artery throughout the modified Henry approach (at the wrist crease (WC), 5 cm proximal and 10 cm proximal) with identification of the branching of the palmar cutaneous nerve and its course along the FCR distally.

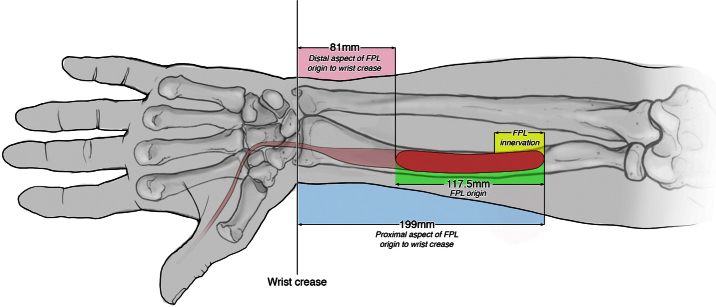

The FPL muscular origin terminated on average 81.5 mm (std dev: 13.5) and started 199 mm (std dev 23) from the wrist crease The FPL footprint on average was 117.5 mm in length (std dev: 11). Branches from the AIN innervated the FPL along the ulnar aspect of the muscle belly along the proximal third of the muscle (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The footprint of the FPL in relationship to the wrist crease.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that there is a changing relationship between the radial artery, FCR tendon and median nerve over the distal 10 m of the volar forearm. Secondarily, the flexor pollicis has a 117.5 mm bony origin with ulnar sided innervation within the proximal third of the muscle. Previous studies have looked at individual anatomic positions of specific key neurovascular structures but not in the context of the whole length of the modified Henry approach. MR scanning has been utilized to identify a 7 mm safe zone on either side of the center of the FCR tendon to avoid damage to the median nerve and radial artery at the level of the watershed line of the distal radius.12 An anatomic study has reported the distance from PCB to FCR was 3.4 mm, median nerve to FCR was 8.9 mm and radial artery to FCR was 7.8 mm at the level of the watershed line of the radius.9 However, the authors of this anatomic study obtained measurements from the center of the FCR tendon, which does not take into account variability in diameter of the tendon itself and makes surgical interpretation difficult.9 We chose to perform measurements from the edges of the FCR sheath to eliminate variability in the tendon width and to mimic the relationship of these structures at surgical dissection.

The neurovascular structures at risk during surgical exposure of the volar aspect of the distal radius include the median nerve and its PCB on the ulnar aspect of the FCR when using the modified Henry approach. The radial artery on the radial aspect of the FCR is at increased risk when using the classic Henry approach. This difference between the modified Henry approach and classic Henry approach has brought forth controversy over which approach decreases potential iatrogenic injury. Iatrogenic injury can be reduced with a more thorough knowledge of the anatomy.12

Neurologic injury after distal radius fractures most commonly affects the median nerve.13 Two to 14% of distal radius fractures that undergo volar plating go on to develop carpal tunnel syndrome most often as a consequence of direct injury to the nerve at the time of fracture displacement, iatrogenic injury caused during the surgical approach or excessive retraction on the nerve.1

This study demonstrated that the median nerve is closely associated with the FCR tendon lying an average distance of 0.1 mm apart at 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease. The separation distance widens to 4.5 mm at the distal wrist crease. Appropriate exposure and direct visualization of the nerve is necessary in cases in which comminution or fracture extension into the shaft necessitates an extended approach. Gentle retraction of the FCR in an ulnarward direction should protect the median nerve during fixation of the distal radius.

Damage of the PCB of the median nerve has been implicated in the development of chronic wrist pain, pillar pain, increased scar tenderness and complex regional pain syndrome. The incidence of complex regional pain syndrome has been estimated to occur in between of 3 and 10% cases after open reduction and volar plating of the distal radius.1, 9, 13 The PCB of the median nerve runs along the trunk of the median nerve for 10–25 mm then moves radially toward the FCR tendon prior to descending between the superficial and deep layers of the flexor retinaculum.3, 14 Two prior studies documented the PCB bifurcates from the median nerve between 32 mm and 44 mm proximal to the wrist crease.3, 10 The present study found the separation point to be an average of 48.6 mm proximal to the wrist crease. We never encountered instances in which the PCB crossed deep to the FCR tendon; instead we noted that the PCB runs along the ulnar border of the FCR tendon sheath. In the modified Henry approach, incision of the sheath along the radial edge would establish a safety interval of approximately 5 mm, the width of the FCR tendon, between the area of incision and the PCB.

Radial artery injury with distal radius fractures, an exceedingly rare event, can occur as the result of a direct tear of the vessel by the fractured bone. One must remain vigilant of the radial artery's proximity when approaching the distal radius volarly.1 Iatrogenic radial artery complications usually manifests as a direct laceration of the vessel at the time of surgery. Latent pseudoaneursym, arteriovenous fistula formation and lymphedema have also been reported.9 Our study found a slight increase in the distance between the radial artery and the FCR tendon distally. The average distance of the artery from the FCR tendon increased from 4.2 at 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease to 4.4 at 5 cm proximal to the wrist crease to 5.3 mm at the level of the wrist crease. Dissection of the radial artery would not be routinely necessary during volar approach to the radius and the vessel would be protected if dissection was deepened through the sheath of the FCR tendon.

The second aim of this study was to look at the bony origin of FPL muscle and its innervation. Flexor pollicis longus weakness has been observed after surgery. This weakness has been attributed to elevation of the FPL muscle origin to gain access to the radius. Our study shows a proximal innervation of the FPL, which is consistent with previous studies.11 This study shows that distance based off a distal anatomic landmark, the wrist crease, instead of proximal landmarks that are not always visible while operating on the distal radius.15 Due to the proximal innervation of the muscle belly, transient FPL function is probably due to the elevation of bony origin of the muscle not from a neurapraxia. If a more proximal fracture or an extension of a distal radius fracture involves the region of the proximal third of the FPL, these branches should be identified and care should be taken to stay radial on the muscle origin on the radius.

One weakness of this study is the number of specimens examined. Though this study examined more cadaver forearms than previous studies, our data is limited to 16 specimens and anomalous relationships are possible between these structures in less common anatomic configurations. In addition, we recognize that the location of the wrist crease may vary in relation to the underlying bony landmarks.14 We elected to use a soft tissue landmark of the wrist crease rather than bony landmarks since bony landmarks can be inconsistent after a displaced fracture.

Our study provides a comprehensive look at the modified Henry approach using the floor of the FRC tendon sheath as the superficial interval when approaching the distal radius. Unlike the classic Henry approach, the modified Henry approach is consistently several millimeters away from the radial artery and the median nerve. The surgeon must however, be aware of the close relationship of the median nerve to the tendon in the proximal aspect of the incision. Retraction of the FCR ulnarly should help protect the nerve. Distally, the PCB is at risk of injury and incision through the floor of the FCR sheath should be performed along the radial edge of the sheath. The FPL muscular origin is 117.5 mm along the radius with an ulnar innervation of the proximal third of the muscle belly that should be protected if operating more proximally however, elevation of the distal third of the FPL muscle should not create an iatrogenic neurapraxia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Berglund L.M., Messer T.M. Complications of volar plate fixation for managing distal radius fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:369–377. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colles A. On the fracture of the carpal extremity of the radius. Edinb Med Surg J. 1814;10:182–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matloub H.S., Yan J.G., Mink Van Der Molen A.B., Zhang L.L., Sanger J.R. The detailed anatomy of the palmar cutaneous nerves and its clinical implications. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:373–379. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koval K.J., Karrast J.J., Anglen J.O., Weinstein J.N. Fractures of the distal part of the radius. The evolution of practice over time. Where's the evidence? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1855–1861. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora R., Lutz M., Hennerbichler A., Krappinger D., Espen D., Gabl M. Complications following internal fixation of unstable distal radius fracture with a palmar locking-plate. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:316–322. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318059b993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drobetz H., Kutscha-Lissberg E. Osteosynthesis of distal radial fractures with a volar locking screw plate system. Int Orthop. 2003;27:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamano M., Koshimune M., Toyama M., Kazuki K. Palmar plating system for Colles’ fractures—a preliminary report. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozental T.D., Blazar P.E. Functional outcome and complications after volar plating for dorsally displaced, unstable fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCann P.A., Clark D., Amirfeyz R., Bhatia R. The cadaveric anatomy of the distal radius: implications for the use of volar plates. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94:116–120. doi: 10.1308/003588412X13171221501186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilyas A.M., Ilyas A.M. Surgical approaches to the distal radius. Hand. 2011;6:8–17. doi: 10.1007/s11552-010-9281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilelli B.J., Patel R.M., Kalainov D.M., Peng J., Zhang L.Q. Flexor pollicis longus dysfunction after volar plate fixation of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:1691–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCann P.A., Amirfeyz R., Wakeley C., Bhatia R. The volar anatomy of the distal radius—an MRI study of the FCR approach. Injury. 2010;41:1012–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis D.I., Baratz M. Soft tissue complications of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2010;26(May):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaynes P., Becue J., Vavss P., Laude M. Relationships of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve: a morphometric study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26:275–280. doi: 10.1007/s00276-004-0226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolderer J.H., Prandl E.C., Keherer A. Solitary paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus muscle are minimally invasive elbow procedures: anatomical and clinical study of the anterior interosseous nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(3):1229–1236. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182043ac0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]